Linda Collison's Blog, page 6

August 13, 2020

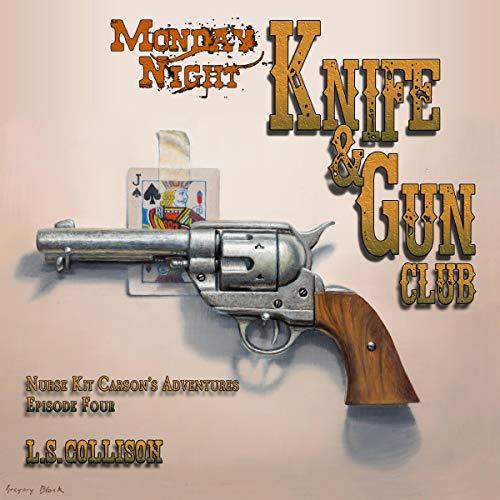

Nurse Kit Carson’s Knife & Gun Club – Monday Night audiobook

While dodging the West’s deadliest virus, nurses Kit and Tonto, along with Doc Halliday, are tasked with infiltrating secret, high stakes card games and stealing scarce medical supplies stockpiled at the High Plains Fort. Will the Vigilantes succeed in bringing healthcare justice to High Plains in America’s new Wild West?

Read ’em and weep cowgirl.

Kit Carson RN’s Knife & Gun Club, Episode Four

May 22, 2020

Monday Night Knife & Gun Club

.

April 12, 2020

Pale Horse, Pale Rider revisited

1918

Many families, especially in the slums, had no adult well enough to prepare food and in some cases had no food at all because the breadwinner was sick or dead. The kitchens of the various settlement houses fired up their stoves and produced huge quantities of simple but nourishing food, soup more than anything else, and distributed it free to the hungry and bedraggled who lined up at their doors with buckets and pans. Volunteers brought the food to those families immured in their tenements by disease. – Alfred W. Crosby, America’s Forgotten Pandemic; The Influenza of 1918, new edition (Cambridge University Press, 2003), pg. 80.

Influenza that killed 30 million people worldwide in the years 1918-1919 — more lives than the World War itself took. Yet over the next hundred years the world, as a whole, forgot that killer pandemic. Except for the historians. The historians and the writers.

What initially led me to read Crosby’s study was my interest in the story Pale Horse, Pale Rider, by Katherine Anne Porter, and my interest in the author herself, particularly her time spent in Denver. That, and my own experiences as a nurse working in Denver, in the 1980’s and early 1990’s.

I don’t remember when I first read Pale Horse, Pale Rider, but I was a young woman, in my late teens or early twenties. I read it again when I was a nurse, and I read it again, as a student of history. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, I downloaded an electronic copy and have read it again.

In prior readings I never gave much thought to the pressure for Miranda, the narrator, to support the war effort by buying war bonds.

‘They are in fact going to throw me out if I don’t buy a Liberty Bond.’

‘The two men slid off the desk, leaving some of her papers rumpled, and the oldish man had inquired why she had not bought a Liberty Bond.’

“With our American boys fighting and dying in Belleau Wood,” said the younger man, “anybody can raise fifty dollars to help beat the Boche.”

“You’re the only one in this whole newspaper office that hasn’t come in. And every firm in this city has come in one hundred per cent.”

She would have to raise that fifty dollars somehow, she supposed, or who knows what can happen?

Drawing from the Philadelphia Inquirer, Crosby describes the town crier in colonial dress , a Boy Scout with an American flag, and solicitors to sell bonds parading through neighborhoods of Philadelphia. Crosby sheds light on the importance of the war bonds and the pressure exerted upon Americans to support the war effort.’ “It was,” said the Secretary of the Treasury, “the largest flotation of bonds ever made in a single effort anywhere or at any time,” and the American people bought it all up in the middle of the nation’s worst pandemic,’ Crosby tells us, quoting from William McAdoo’s Crowded Years. On September 28, 1918 an estimated 200.000 people gathered for the parade kicking off Philadelphia’s Fourth Liberty Loan Drive. Similar parades were happening all over the country, yet health officials were not alarmed.

Two weeks later Philadelphia was under attack – not by the Germans but by the Germs. Seven hundred died of flu and pneumonia in the first week of October, 2600 the next week, and 4,500 the week after that – in Philadelphia alone. Hospitals were overflowing, makeshift hospitals set up. Scores of medical professionals and ancillary staff fell ill, becoming patients themselves. On a single day 711 deaths were reported to the Philadelphia Health Department. The next day Jay Cooke, one of the leaders of the city’s wealthy, grumbled to the press that “it seems few people realize we are facing a serious crisis.” He was referring to the fact that Philadelphia had dropped behind in its Liberty Load Drive, Crosby says, drawing from the Philadelphia Inquirer, 17 October 1918.

Ultimately, the 1918 pandemic killed more Americans than the world war. Than either world war. Yet until the COVID-19 pandemic, few had heard of it. Except for 20th century historians, medical researchers, and readers of Katherine Anne Porter. ‘Death is death, said Miranda, and for the dead it has no attributes.’

I will return to this story of Porter’s because it obviously has much to tell me.

December 19, 2019

Fanny Palmer Austen, Navy Wife

Navy Wives Aboard British Warships

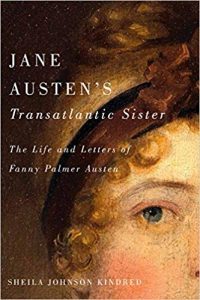

A critique of Jane Austen’s Transatlantic Sister; The Life and Letters of Fanny Palmer Austen

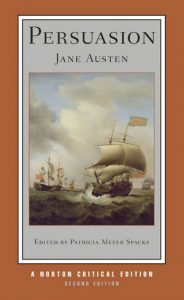

Jane Austen was a social realist in portraying everyday life of the gentry in England during the Georgian era. Two of her novels, Mansfield Park and Persuasion have nautical elements and naval characters. Sheila Johnson Kindred, having studied the letters of Fanny Palmer Austen, Jane Austen’s sister-in-law and wife of her younger brother Charles, an officer in the Royal Navy, reconstructs the brief life of this woman. Based largely on correspondence from 1810-1814, and on Fanny’s diary, she concludes that Fanny, who spent two and a half years living aboard ship with her husband, Captain of HMS Namur, was the basis for Mrs. Croft, the wife of Admiral Croft in her novel Persuasion.

Jane Austen was a social realist in portraying everyday life of the gentry in England during the Georgian era. Two of her novels, Mansfield Park and Persuasion have nautical elements and naval characters. Sheila Johnson Kindred, having studied the letters of Fanny Palmer Austen, Jane Austen’s sister-in-law and wife of her younger brother Charles, an officer in the Royal Navy, reconstructs the brief life of this woman. Based largely on correspondence from 1810-1814, and on Fanny’s diary, she concludes that Fanny, who spent two and a half years living aboard ship with her husband, Captain of HMS Namur, was the basis for Mrs. Croft, the wife of Admiral Croft in her novel Persuasion.

Although officially prohibited from sailing on navy ships except by consent of the Admiralty or commanding officer, in reality women did sail and live aboard British Naval warships during the Georgian era – as passengers and as wives accompanying officers, seamen, marines, and soldiers in transport. Fanny Palmer Austen was one of these naval wives. The author posits that her sister-in-law Fanny provided Jane with a female perspective on naval life and society and was the inspiration for the female naval characters in Jane Austen’s novel Persuasion, particularly Admiral Mrs. Croft, who remained with her husband throughout his career, living and traveling onboard with him.

Combining biography with social history and women’s history, Kindred reconstructs the life of one woman, from her birth and upbringing in St George’s, a port town and naval base on Bermuda, to her life married to a young Royal Naval officer, concluding with her death (aboard ship, where she had shortly before given birth to the Captain’s fourth daughter). The historian employs the letters written by Fanny herself and letters written about Fanny, Fanny’s pocketbook, Admiralty records, and other sources including journals and private papers. The author cites the diaries of Betsy Fremantle, who lived with her husband Captain Thomas Fremantle, on his vessels for a period of seven and a half months during 1796-97. She also points out that the warrant or standing officers, such as the master, the carpenter, the boatswain, etc., were by tradition allowed to have their wives and children live aboard with them, in spite of the Admiralty prohibition. Kindred says Fanny employed the services of at least one of these women from time to time. Where there are men and women, there will be children. In May 1814 Fanny and her daughters went to London because the “odious measles have got amongst the Children belonging to the Ship” (95).

Aboard and onshore, wives played a role in their husband’s careers, as the navy was a social organization as well as a military one. Influence, interest, and relationships were important to advancements and assignments. The author says Fanny and Charles must have spent a good part of 1813 discussing his career options, his chances for a favorable posting and the possible consequences for her. Writing to James Esten if Charles “should be fortunate enough to get a Frigate before the American war is over he will certainly endeavor to get out on that station & has promised that I shall accompany him” (130). Jane Austen, Kindred says, had a message about naval life to convey in Persuasion which champions the navy’s social group as morally superior to the landowning gentry and aristocracy, and to offer women as well as men happier and more vital social roles (202).

The biographer spends some time and effort to show that Fanny was the inspiration for the Admiral Croft’s sea-going wife, an inference that’s impossible to prove. Fiction is an art and craft of synthesis and confabulation, even social realism such as Jane Austen excelled at. The important hypothesis is that the Admiral and Mrs. Croft are probable characters, drawn from real life. Their relationship and living situation mimics that of her brother and sister-in-law, the Captain and Mrs. Austen – Charles and Fanny – whom the writer Jane knew very well.

Charles and Fanny, a young married couple in love, spent as much time together as possible, including over two years onboard his commands. Austen presents the character Mrs. Croft, the Admiral’s wife, as a supportive naval wife who enjoys life aboard or on a station abroad, as long as she is with her husband. This is surprising to some of the other characters in the story as it may be to modern day readers who mistakenly believe English women stayed home and had little to do with the navy while their men went off to war. Some couples, like the captain and Mrs. Austen, chose to stay together aboard the warship. The author touches on but does not fully examine the financial advantages for a young officer who cannot yet afford a house ashore, to keep his wife afloat (86). Nor are many inconveniences brought up – possibly because Fanny never mentioned them in her letters or her diary. She also has a female servant living on board to help her with the children, but Fanny has little to say about Nancy (104). One wonders what life aboard was like for her and how she fit in with the other servants and seamen.

Overall, The Life and Letters of Fanny Palmer Austen succeeds in revealing the life of a naval wife during the late Georgian era through a social history, micro-history, and women’s history approach. For some couples, the dangers, discomforts, and adventures of living together on an active naval vessel were welcomed. Fanny and Charles Austen were among them.

November 24, 2019

Another dysfunctional Thanksgiving

Another dysfunctional Thanksgiving!

Time to dust off the china, chipped and mismatched

like us, incomplete yet serviceable

broken and lost over the years

and added to, piece by piece

partial sets of dinnerware entrusted to me for safekeeping

the salvage of shipwrecks and divorces

fairy tales with bitter endings told in bread-and-butter plates and gravy boats

Dear Lord, forgive us

Ours is not the candle-lit table pictured on the cover of Pottery Barn

We are not those people caught in a moment of laughter, raising Riedels for a toast,

the plastic turkey posed on a hand-painted platter made in Portugal or Poland, some distant oppressed country our ancestors fled

in search of freedom and a job

So bring your new girlfriend, your old boyfriend

Bring the guy next store

Manny? sure, he’s family

Bring your ex husbands — bring my ex husbands —

We’re a family of steps leading where

I don’t know but bring your excess baggage

if you don’t mind sleeping with it

we’ve got plenty of room

Dogs? Yeah,

they’re family too, and so much more thankful

Yet they too will show their teeth

before the day is done

snarling and quarreling over

slivers of fat and the

wishbone gets thrown out with

the trash

again

Come one, come all, for yet another dysfunctional Thanksgiving!

If you’ve got a car that will make it

if your battered heart can take the journey

over the river and through the woods

to grandmother’s house where the smell of roast turkey

like regret,

whets the desire for what never was

Let’s give thanks for the miracle of water turned into wine

fermented grape to ease the heart’s burn

proof that Jesus loves us every one

Pass the stuffing please, and the gravy

a little lumpy but heartfelt

plenty of God’s grace to go around

Under the table the dogs pray

with pure and trusting hearts

while outside in the forest bears settle in for a long sleep

and a generation of acorns buried and forgotten

wait for spring.

— Linda Collison, 2012

November 11, 2019

Kimberley Reeman’s Dark Wisdom

Spouses and lovers are more than muses.

Sometimes they function as silent partners in the creation, freely allowing their mate the needed time and space to work. As silent partners they can provide insight, critique, emotional support — and sometimes financial support. Most importantly, spouses and lovers believe in their partner’s vision, honoring the essence of their work and the need to produce it.

Sometimes spouses and lovers are artists in their own right.

When Helen Hollick invited me to join a fleet of bloggers hosting the author Kimberley Jordan Reeman on my Sea of Words, I naturally jumped on board. Admittedly, I wasn’t familiar with her name or her writing. Her husband, the late Douglas Reeman, was a well-respected author of historical naval fiction whose Georgian era Bolitho series I was familiar with. I wanted to learn more about the late Mr. Reeman’s life and inspirations, certainly — but I was equally curious about Mrs. Reeman’s writing. And I wanted to know how she and Douglas may have worked together and influenced one another during their years together.

Kimberley Jordan Reeman

A spouse can make or break a writer in so many different ways. Wives and husbands are seldom given their due credit, save a thanks in the author’s introduction or afterword. The work we produce is our own, yet it is always influenced by others, especially those we love and depend on. I asked Kimberley about her writing relationship with Douglas. Had they influenced each other? What role had she played in his prolific writing and publication? While I waited for her to write her guest post for Sea of Words, I delved into her fiction –a surefire way to get intimate with a writer’s mind and heart.

Reeman’s Coronach is an ambitious novel, deeply felt. The word coronach (I had to look it up) is a song of lamentation for the dead, often played on the bagpipes. Wikipedia defines it: “A coronach (also written coranich, corrinoch, coranach, cronach, etc.) is the Scottish Gaelic equivalent of the Goll, being the third part of a round of keening, the traditional improvised singing at a death, wake or funeral in the Highlands of Scotland and in Ireland.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coronach

Already my skin is tingling and my heart beats like a bodhran. Yet Reeman’s Coronach is not contained within an island, nor does the song end on the moors of Culloden.

Whereas Douglas Reeman set his fiction at sea, Kimberley Reeman crosses seas in her novel. Her writing is at once muscular yet rich; brutal yet exquisite, peopled with complex men and women in conflict. I am in the midst of reading it right now, enjoying it, yet at times drowning in it. Coronach is definitely not To Glory We Steer, the opening novel of Douglas Reeman’s Bolitho series — written under the name Alexander Kent This series, as all of Reman’s nautical books are admired for their perceived verisimilitude in capturing the world of the Royal navy. His portrayal of shipboard life is generally credited to Reeman’s own experience in the Royal Navy, beginning in World War II, a sixteen-year-old midshipman. He served aboard destroyers and torpedo boats in the North Sea, the Atlantic, and Mediterranean campaigns. Reeman held a variety of jobs after the war, returning to active service when the Korean War broke out. In 1958, having published two short stories, Douglas wrote the novel Prayer for the Ship, published in 1958. Ten years later the first of his Bolitho novels was published, beginning the exploits of Richard and Adam Bolitho, under Reeman’s pen name, Alexander Kent. More about Douglas Reeman/Alexander Kent’s work at douglasreeman.com

From the opening page I discovered Kimberley has her own voice, quite different from her late husband’s. She writes of men and women in tumultuous times of revolution, delving into their hearts and minds to expose what drives them. It’s not always pretty but it is vividly imagined and voluptuously written. The raw emotions, the consequences, are as real as the history behind it.

Women as muses, women as lovers, women as editors, and women as wives have long been influencing male writers and are seldom recognized, except in a dedication or an end note. Certainly the reverse may be true. I asked the author of Coronach about her working relationship with Douglas and a glimpse into his writing process – and hers. Thank you Kimberley for sharing this with us. Readers and writers — enjoy and be inspired!

THIS DARK WISDOM

written by KIMBERLEY JORDAN REEMAN FOR Collison’s “SEA OF WORDS”

Kimberley and Douglas in Tahiti, 1986. Courtesy of Kimberley Jordan Reeman.

It was a meeting of minds. It became a joining of souls. This is how it began.

Once upon a time (because all fairytales begin with these words) on a Saturday morning in Toronto, a young, aspiring novelist stood in her local library with a battered paperback in her hand. Its title was Signal⸺ Close Action! and she had never heard of the author, Alexander Kent. And because since her teens her mind had been as much in 1746 as in the real world, she said to herself, possibly aloud: “I wonder if this guy really knows how to write about the eighteenth century.”

I checked the book out. I read it. He did. I was hooked.

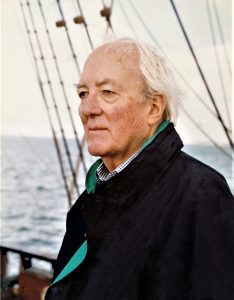

Douglas aboard the “Cutty Sark,” 1968; Courtesy of Kimberley Jordan Reeman.

Fast forward to the evening of June 6th, 1980, at Toronto’s Harbourfront cultural centre. Alexander Kent, whose real name was Douglas Reeman (I had always sensed ‘Alexander Kent’ was a pseudonym) had just read aloud, over the sound of rain drumming on the roof of the aptly named Brigantine Room, the first chapter of A Ship Must Die, the book he had come to Canada to promote. He had spent the day doing radio and television interviews, mostly talking about D-Day, and he hated reading aloud, although in years to come he would read the day’s work to me, doing all the accents, without any compunction or shyness. Then he finished reading, and the publishing representative said to the audience: “Any questions?”

There was a long silence, and I thought, it’s now or never, and stood up and said, “At the end of The Flag Captain, Richard Bolitho is obviously romantically involved with Catherine Pareja. And then when we get to the next book in the series, there’s no mention of her. Whatever happened to Catherine Pareja?”

If he was tired at the end of what had been a grueling day, he didn’t show it. He looked down at me kindly from the stage, over his reading glasses, and said in that beautiful voice of his, “I don’t know. I haven’t written the book that goes between those two yet.”

He would always say afterwards that I was the only person who had ever asked him a question he couldn’t answer.

He invited me to write to him and gave me his address, not the address of his publisher in London but that of this beloved house where I still live. We wrote to each other for four years, and gradually our friendship deepened: my letters sustained him after the death of his wife in 1983, when he fell into a black spiral of depression that almost cost him his life. He was invited to act as technical adviser on the set of “The Bounty”, then filming in French Polynesia. He made the punishingly long flight to Papeete and, not liking the situation on set when he got there, recklessly flew home three days later. As a result, he developed a deep vein thrombosis, which became a pulmonary embolism. It could have killed him.

I knew. I don’t know how I knew, but I sensed very strongly that there was a crisis, and when his next letter arrived confirming what had happened I think I cried with relief. I was already keeping his letters under my pillow, and now they began to arrive with such frequency that the woodsy scent of the desk drawer in which he kept his stationery still clung to the pages.

Douglas aboard the “Grand Turk”, Spithead, 2005; Courtesy of Kimberley Jordan Reeman.

On the evening of July 9th, 1984, four years after our first and only meeting, he walked across the lobby of the splendid old Royal York Hotel in Toronto and opened his arms to me. Later that evening, he asked me to marry him.

We were married in St. James’s Cathedral in downtown Toronto on Saturday, October 5th, 1985, and were inseparable for the rest of his life.

He used to say we lived in a house full of flowers and music. It still is, as I cut my roses in the summer and, in their season, the flowers of spring and autumn. And there is music again, although still some I can’t bear to hear. But it was also a house full of laughter. He was romantic and sensitive and easily hurt, and a chronic worrier, and as devoted to his work as I am to mine, but he had a wonderful sense of humour, too, and he was very, very funny. He loved good wine and good conversation and the company of friends: he loved me and our home and our cats: he was a man’s man and a woman’s man, with a genuine respect and understanding. I never felt that he regarded me as anything but his equal.

What did I mean to him? Let me quote him, in conversation with George Jepson of “Quarterdeck” magazine.

What role does Kim play in my work? The same role she plays in my life. She is everything to me. She edits, writes the blurbs, takes the author’s photos, does the Bolitho newsletter with me, shares the research and the ship visiting and the PR and signing sessions, handles the computer side of things and the e-mail. She is my right hand and partner in everything I do, as well as being a hugely talented writer. As I said in the dedication to her in my latest book, written under very difficult circumstances, I couldn’t have done it without her.

And so, like the fairy tales, we did live happily ever after, until the end. There is always an end.

In the movie “Lady Hamilton” a young streetwalker asks the destitute Emma Hamilton, who has fallen, as she did in reality, into a vortex of alcoholic depression after the death of Horatio, Lord Nelson, “What happened then? What happened afterwards?” Vivien Leigh as Emma, with immense poignancy, conveys the absolute nadir of grief when she answers, “There is no then. There is no afterwards.”

But there is. The black tsunami of grief overwhelms you, and you never know what’s going to cause it: a time of day, an angle of light, a room, a forgotten photo falling out of the pages of a book, certain music, a significant date. It will take you and break you and drive you to your knees, until you think there will never be an end to it, that your heart, now broken, can never shatter again, and yet it does, again and again. And this pain, this mourning, this giving of your heart to be splintered because you loved, confers a dark wisdom: a knowledge of life and death. You have crossed a river of shadows into another country, where no one who has never yielded love to death has walked.

I brought this dark wisdom to Coronach: all my understanding of great love and great pain. I wove the story from the warp and weft of history, to tell truths more compelling than fantasy. I saw war through the eyes of a man who had lived it, and who had trusted me enough to share his experiences of it, and I brought those truths to Coronach and wrote of them unflinchingly and without compromise. I brought, I hope, compassion. And what I would hope you, the reader, take away from this book is not its darkness, which is authentic darkness, but a memory of the love, courage, honour, loneliness and human frailty of my people, whose lives become the very fabric of history.”

About the background of this epic saga Kimberley has this to say:

“It is not necessary to look further than the history of Canada, and Toronto itself, for the genesis of Coronach: a vast country explored, settled, and governed by Scots, and a city, incorporated in 1834, whose first mayor was the gadfly journalist and political agitator William Lyon Mackenzie, a rebel in his own right, and the grandson of Highlanders who had fought in the ’45. The Vietnam War, also, burned into the Canadian consciousness the issues of collateral damage and the morality of war; and from this emerged one character, a soldier with a conscience. In unravelling the complexity of his story, Coronach was born. — KJR

***

Kimberly Jordan Reeman was born in Toronto, graduating from the University of Toronto with a Bachelor of Arts (hons) in English literature in 1976. She worked in Canadian radio and publishing before marrying the author Douglas Reeman in 1985, and until his death in 2017 was his editor, muse and literary partner, while pursuing her own career as a novelist.

She has always been a spinner of tales, telling stories before she could write and reading voraciously from childhood. She cites Shakespeare, Hardy, Winston Graham and the novels of Douglas Reeman and Alexander Kent as her most profound influences. From Graham, who became a friend, she learned to write conversation, to eavesdrop as the characters spoke; from the seafaring novels of Reeman and Kent, which she read years before meeting the author, she came to understand the experience of men at war. Read more about Kimberley Jordan Reeman and her novel Coronach on the Reeman website douglasreeman.com/kim-reeman

This post concludes a tour of blogs featuring Kimberley Reeman and her historical saga Coronach. I have followed and participated with great interest. If you missed some of the ports of call and want to learn more of this writer and of her late husband, author Douglas Reeman, please sail by for a look:

4th Nov Richard Tearle Slipstream

5th Nov Ross Wilson books@nauticalmind.com

6th Nov Annie Whitehead EHFA (English Historical Fiction Authors

7th Nov Sarah Murden All Things Georgian

8th Nov Amy Bruno Passages to the past

9th Nov Anna Belfrage Stolen Moments

10th Nov Antoine Vanner Dawlish Chronicles

11th Nov Helen Hollick & Kimberley’s own blogs

12th Nov Linda Collison Sea Of Words

October 13, 2019

John Nichol, mariner and memoirist.

John Nichol, mariner. I would have liked to have known him. Re-reading his episodic memoir (I first read it at sea on a Pacific voyage – the same waters he crossed more than 200 years before) it feels as though I do know him, as if he was an ancestor maybe, or an old lover from a past life. A mariner like Robert Hay, also from a Scottish family but Nichol was of the generation before Hay. Both men mention Robinson Caruso as a favorite novel of their youth.

John Nichol, mariner. I would have liked to have known him. Re-reading his episodic memoir (I first read it at sea on a Pacific voyage – the same waters he crossed more than 200 years before) it feels as though I do know him, as if he was an ancestor maybe, or an old lover from a past life. A mariner like Robert Hay, also from a Scottish family but Nichol was of the generation before Hay. Both men mention Robinson Caruso as a favorite novel of their youth.

Like Hay, John Nicol was literate, sensitive, and observant. He wrote with insight and genuine feeling about those incidents in his life that affected him, that caused him to wonder. Those incidents that changed him — or at least those incidents he remembered years later, as being worth writing about.

Many of John Nicol’s memories include women. He noticed women. He records them in his memoirs, beginning with his mother who died when John was young, giving birth to a fourth sibling, leaving his father, a cooper, to raise five children. He tells an early story of a trip to London with his father. Here, he fought an English boy over a dead monkey floating in the Thames. “I had not seen above two or three in my life. I thought it of great value.“He stripped naked, plunged in the river for it, and had the soggy corpse stripped from his hands by the other boy, whom he fought, naked and wet, and won. His father gave him a beating for fighting and “staying my message; but the monkey’s skin repaid me for all my vexations.”

John Nichol would prove himself to be a lover, not a fighter, some years later aboard a convict transport ship where he fell in love with, protected, and fathered a child with one of the female convicts, Sarah. Every man on board took a wife from among the convicts, he relates. His was Sarah Whitlam, whom he “courted for a week and upwards, and would have married her on the spot had there been a clergyman on board.” Sarah, like many others, had been transported for stealing – her sentence seven years. “I knocked the rivet out of her irons upon my anvil, and as firmly resolved to bring her back to England when her time was out, my lawful wife, as ever I did intend anything in my life. She bore me a son in our voyage out.”

A cooper like his father before him, Nicol served aboard warships, whalers, merchantmen and transports alike. In his journeys he twice circumnavigated. Coopers were in great demand in that century. He served aboard Goliath (74 guns) under Captain Foley in the battle of Aboukir Bay. His station was below-decks, assisting the gunner. He mentions the gunner’s wife as being of good comfort during the battle, bringing them both a drink of wine to fortify them. John tells of several women aboard who did their part. Several of them were wounded in the action and one woman, from Leith, died as a result of her wounds. “One woman bore a son during the heat of action.”

While he relates plenty of masculine action in his adventures, Nicol notices the women everywhere he goes and remarks on them. In doing so he makes them visible to us, and alive. They too, are part of the history. Real women were there, as mothers, mates, wives, lovers, convicts, slaves, prostitutes, passengers — and occassionally disguised as men, working alongside them.

October 9, 2019

Memoirs of Robert Hay

More fiction has been written about naval officers aboard British warships during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, I would guess, than any other single period in history. The protagonist is typically a young gentleman who, through a multi-volume series, rises in the military ranks to Captain or Admiral, while out-gunning, out-maneuvering, and outsmarting the French and the Spanish. This sub-genre of historical fiction remains popular, as evidenced by the many book titles, series, games, films, and on-line forums that endure. Fortunately, authors of historical naval fiction set in this era have many primary sources — first hand accounts — to draw upon, should they desire to add verisimilitude to their settings, plots, and characters.

Among my personal favorite primary sources are those memoirs from “the lower deck” — that designated section of a warship that is inhabited by the warrants, seamen, and the landsmen. Even at sea, British society was highly stratified. Landsman Hay is one of those revealing memoirs.

Robert Hay began his nautical career as a “shoe boy,” or officer’s personal servant. He was fourteen years old, unskilled and inexperienced as a mariner. Although young Robert would acquire specialized nautical skills over the next eight years, including rudimentary navigation and ship carpentry, he identifies himself in the book’s title as “Landsman Hay.”

His story begins in Paisley, Scotland, where Robert lived with his parents and siblings. Here, he worked with his father as a weaver, memorized multiplication tables to relieve the boredom at the loom, and read whatever fiction he could get his hands on. Robinson Crusoe was a novel he read “over and over with avidity and delight.” The story might have been the catalyst for his life-changing decision. He writes “I regretted that I was not following that line of life which would put me in the way of meeting similar adventures.”

In the very next sentence Hay tells us he left his parent’s home that July of 1803, the summer he turned fourteen, setting out for the port of Greenoch on the River Clyde, more than 25 miles from Paisley. He intended to join the navy, and succeeded. A short time later his father and sister Jean followed him to Greenoch and found him aboard the press tender. His father tried to buy him back from the navy, but hadn’t the means. He gave him a Bible to read. His sister Jean gave him some sewing supplies for mending, a set of seaman’s clothing, and “a little bread of my mother’s preparation.”

Hay’s autobiographical account is interesting on many levels. That the son of Scottish weaver was an avid reader, had dreams beyond shuttling a loom, and ran away at the age of fourteen for the sake of adventure (and perhaps to improve his lot in life), rings out through the story. The author describes this brief, last meeting with his father:

“On deck I found, to my great surprise, my father. At our meeting, at which both joy and grief mingled, I also observed in his paternal countenance a mixture of anger and pity, in that he had been to much expense and toil in bringing me forward thus far, and now when I might have begun to be useful to him, and of financial assistance in bringing up the younger branches of the family, I had basely deserted him. Still, he looked on me with a kind tenderness and immediately applied with urgency to the captain for my discharge. But this would not be obtained without advancing a sum of which he, alas, was not master.”

Throughout the memoir the Scotsman Hay gives us a candid look at life below-decks of British Naval Warships during the Napoleonic War era. Hay doesn’t try to regale the reader by recounting well-known historical events, glorifying British officers, dissecting battle strategies or analyzing campaigns. His story is a personal one; his intended audience is his children. The writer is concerned with his own existence and purpose, and therein lies its charm, its believe-ability, and its importance and interest as social history.

Robert Hay begins his shipboard life as an officer’s servant. On first being inducted, he was sent on board the Salvador del Mundo, a three-decker taken from the Spanish and anchored in the harbor as a guard ship for temporary accommodation of seamen. Hay describes the lower deck as a marketplace of commodities of every description: “groceries, haberdashery goods, hardware, stationery, everything, in fact, that could be named as the necessities or luxuries of life. Even spirituous liquours, though strictly prohibited, were to be had in abundance, the temptations of the enormous profits arising from their sale overcoming any fear of punishment.” Hays goes on to say the greater number (of the regular ship’s crew) kept their wives and families on board, it was pretty much crowded day and night.” Indeed, this presents a different picture of a naval ship in wartime than we are generally given in historical naval fiction of the period.

After eight years at sea (his adventures include his desertion from the navy and subsequent impressment) Hay returns home to Paisley to find that his father has died. It is rather like an odyssey, an epic adventure of an 18th century British seaman. Yet, written for his children, not for a commercial audience, making it all the more believable.

Upon his return, a young man of twenty-two, Robert’s mother provides him the means to continue his education in navigation and bookkeeping. In chapter one Hay had credited his mother as being very economical. After her husband’s death she made the decision to provide an advanced education for her son, newly returned from the wars. As a result, the former landsman Hay got work as a steersman before becoming captain of one of the trading boats on the newly completed Ardrossan Canal (a railroad, in this century).

A year later he advanced to company clerk and storekeeper, married, and started a family. Hay describes his wife as a woman of “neither beauty nor fortune but as I myself possessed neither, I had no reason to complain of the want of them on her part… She had a pair of excellent hands, an amiable disposition, and an agreeable temper, and indulged, moreover, a strong desire to promote my comfort and happiness. What more could I desire?” Notice how he remarks on her hands, a landsman’s most important feature.

Robert Hay wrote his memoir between September 1820 and November 1821. Afterward, he repurposed some parts of the manuscript for a series of articles for the Paisley Magazine, under the pen name ‘Sam Spritsail.’ It appears Robert Hay was not only a seaman but a writer as well.

Landsman Hay; The Memoirs of Robert Hay is available from Seaforth Publishing. The 2010 edition includes an editorial note and introduction by author, BBC editor and radio producer Vincent McInerney, a map, and end notes. Highly recommended.

July 23, 2019

Women Aboard: Meriem Jo Ann Boussoauoar at the helm

Meet Meriem Jo Ann Boussouar — novice sailor, boat owner, Gold Star mother, and grandmother.

Meet Meriem Jo Ann Boussouar — novice sailor, boat owner, Gold Star mother, and grandmother.

After my son, Sgt Kyle Thomas, was killed while serving in the military, I had this big idea, that I wanted to learn to sail. I felt like it would help with my grief and get my mind focused on learning something new. Kyle was killed 2 years ago on the night of Memorial Day in a M1 Abrams battle tank roll over. He left behind his girlfriend Jessica and a 28-day-old baby girl named Devina Jayde. Devina was born with Albinism and is a beautiful 2-year-old with pure white hair! I also have 2 daughters and a total of 6 grandchildren.

I started looking at boats that would be good for a beginner and wouldn’t break the budget and purchased a Chrysler 22. It needed a little work but nothing I couldn’t handle. I cleaned the boat inside and out, got a newer outboard and replaced some wiring and navigation lights. I also replaced the bilge pump. I named her “Gold Star” since I am a Gold Star mom. Today, I sailed solo for the first time. I had a wonderful time all by myself on Pensacola Bay in Florida. I had dolphins swimming beside me! I just love it and it’s very healing for my soul to be out on the water! I have the boat in a slip at a small marina just 2 miles from my house. Thank you for allowing me to be a part of your group! I still have a lot to learn!

Every woman sailor has her story about her “first time.” Falling in love with sailing – be it racing, weekend pleasure sailing, long distance voyaging, or simply living afloat. You’re never too young or to old to get on board and learn the ropes. Mature women take to sailing quite readily, as I can personally attest to.

Many of my novels were inspired by my experiences afloat — namely, the Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventures, and Water Ghosts. Currently I’m at work on another historical novel set in Portsmouth, England, and afloat on a British naval warship. I continue to be inspired by real women, my contemporaries, who have set sail. Meriem is one of them.

21st century films featuring females at the helm:

Maiden (2018) A documentary about the first ever all-female crew to enter the Whitbread Round the World Race in 1989.

Adrift (2018) Based on a true story about two sailors, one man, one woman, crossing the Pacific during hurricane season to deliver a sailboat.

Maidentrip (2013) A documentary about 14-year-old Laura Dekker who sets out on a two-year voyage in pursuit of her dream to become the youngest person ever to sail around the world alone.

April 12, 2019

Read ’em & weep: Sunday Night Knife & Gun Club

Come alone and come armed.

~ High Plains Vigilantes for American Justice

My stomach did a flip- flop, my fingertips tingled. Carefully I put the slip of paper back in the envelope and stuffed it inside my Kevlar vest. There must be some mistake. Not to mention, the Watering Hole was such a dive. Only the drovers and the dregs drank there. — from Sunday Night Knife & Gun Club; Episode #3 of Nurse Kit Carson’s Adventures, a series of connected short stories featuring a jaded nurse in America’s dystopian Wild West.

That evening seven of us gathered at a convenient bar.

Gloria, Stacy, Tamra, Christa, Molly, Bob and I. We took turns reading aloud from my short story in progress.

Gloria, Stacy, Tamra, Christa, Molly, Bob and I. We took turns reading aloud from my short story in progress.The evening was not only a lot of fun, it was also instructive to the writing (and drinking) process. Specifically, I found it useful to hear the words, the dialogue, spoken aloud, out of the mouths of critics I trusted. They read it cold, no rehearsal. My story became a shared story, it became interactive as the readers took on accents and attitude when they put on the “reading hat” – a cowboy hat passed around the table to signify whose turn it was. Other props included a stethoscope and a toy pistol. Commeraderie, food, and drink was involved; it would have been entertaining no matter what. But it was valuable to me as a writer because like a director at a table reading I heard what worked, what needed work, and what just plain sucked. As a bonus, I got some new ideas to include. The table reading was so fun I’ve decided to make it a regular part of my writing process. Join me?

Sunday Night Knife & Gun Club

, a 29 page installment, will make its debut on Amazon’s Kindle platform May 1, 2019 for a whopping 99 cents.

Sunday Night Knife & Gun Club

, a 29 page installment, will make its debut on Amazon’s Kindle platform May 1, 2019 for a whopping 99 cents.A big thank you to Susan Keogh for editing, to Lawrence Gregory for providing editorial feedback, to M.G. Manelis for designing the covers for both Saturday Night and Sunday Night Knife & Gun Club! And a thanks to Albert Roberts for designing the cover to the original short story, Friday Night Knife & Gun Club.

Kit Carson, RN

The winter had been a long one and it was not yet spring. I was driving to work, late again, mind busy, overflowing with to-do lists, should-have-done lists, the occasional misplaced memory blowing through like a random tumbleweed. Last week’s lynching, the way the dead man’s boots twitched, a dog dreaming. Tonto’s forearms, his concentration when he draws his bow (a warm tingling down south, picturing his muscles tensed, the arrow poised). Those men we left for dead down in the hospital morgue. Random images. Floaters. Blink, they’re gone and a new day’s shit pile to deal with.

My pickup, a Dodge Power Wagon, galloping along with never a word of complaint. Oil change and new tires all the way around – that put a dent in my charge card but I felt indestructible in that badass machine. Love my sexy set of wheels, she’s fully restored (except for a broken window and glove box latch) and only five more years of payments! Lately, a family had taken up residence in the back, hanging a blue plastic tarp over the bed, tent-like, to keep out the sleet and snow. Beneath the tarp a string of lights lent a bit of cheer to the situation. I’d never actually seen any of them, they were invisible to me, but I couldn’t help notice little scraps of their existence. A glove dropped in the snow. An empty water bottle under the wheel. Sometimes when I got into the cab I smelled green chili and pork simmering in the back. But I kept my blinders on. Hell, I had enough to worry about looking after my own. Those people were no concern of mine.

Traffic in town was heavy that Sunday night, a regular stampede. Used to be Sundays were slow but lately there’d been a rush of interlopers to the city of High Plains and the whole Front Range. They came for the silver, they came for the gold, they came for the oil and gas, they come for the dope. It’s boom or bust baby, and High Plains was booming. Me, I’m practically a native, I’ve got the bumper sticker to prove it.

I stepped on the gas and was making up for lost time when I saw a lasso of blue and red lights in the rearview. Shit damn hellsafire, I don’t need this.

Braking and signaling (and hoping my lights weren’t burned out), I pulled off the highway onto the shoulder. What will I say? Cops and nurses, we supposedly have an affinity or something. I’ll tell him I’m late for my shift and give him the look, you know the look. Maybe I’ll get lucky and he’ll let me off. Unless… What if it’s one of Bully Ratzer’s deputies? What if he knows the dancer Balmy Wether is under my protection, that she’s living under my roof, babysitting my kids, taking online courses to get her high school diploma? What if he knows she’s ready to rat out the sheriff of High Plains?

A flashlight in my face, a tap on the window. “Roll ’em down, cowgirl.”

My stomach, in knots. “It won’t roll down,” I said, speaking loudly, so he could hear me through the glass. “It’s broken. The window’s broken.”

“Keep your hands where I can see ’em.”

I gripped the steering wheel to keep my hands from shaking.

“Now open the door. Easy does it, nice and slow. Keep your right hand on the wheel.”

I did as he bid.

“Atta girl.”

The hombre was tall. Over six feet, I reckoned. I couldn’t even see his face way up there.

“Now, let me see your papers. Driver’s license, registration, proof of insurance. No sudden moves, cowgirl. ”

The click of a safety being released triggered my heart rate to 130 sinus tach, with a couple of PVCs thrown in. I could accurately gauge its rate and rhythm because heartbeats are my business. Critical care and emergency nursing, my expertise. Swallowing hard, I reached over to open the glove box and the damn door fell off in my hand. Of course it did; I had forgotten about the broken latch. Out poured an avalanche of shit – old gasoline receipts, unopened pack of tampons and an empty pack of Marlboros, CPR pocket mask, a box of nine millimeter bullets and a wad of paper napkins from Waco Taco. Somewhere amid the detritus of my road life I found what I was looking for. Handed over my paperwork and awaited my fate.

***

I hope you enjoyed this sample! The short story is available to pre-order on Amazon Kindle, to be released May 1, 2019.