Kevin Maney's Blog, page 4

May 2, 2024

Behind the Music: "Love Loss Hope Desire"

In April, I released a solo music album, Love Loss Hope Desire.

I started writing songs when I was about 40, thanks to my dear friend Mark Holmes. When he and I met in the DC area in the late-1990s, he was an accomplished singer-songwriter. I got my first guitar when I was 13 but had mostly just played by myself in my room. We started casually playing guitars together. He encouraged me to perform and write.

That led to us forming a band called Not Dead Yet to play our songs. I started writing all the stuff that had been bottled up for years. I still love to write music, and now do it mostly for my New York band, Total Blam Blam.

But I wanted to do a solo project, recording songs that were never meant for either band. This album was recorded in a studio in New York with producer Tony Calabro. Tony is more than just a fantastic producer – he’s also a multi-instrumentalist. I played rhythm guitar and harmonica, and he played everything else – except the fiddle on “Pretty Smart Car.” That was provided by Joe Deninzon, the touring violinist for Kansas. (Which I still think is very cool.)

Here’s a little background on each song:

They Needed Anyone: Completely fictional, but when I wrote it I was living in a suburban neighborhood with a lot of stories of troubled marriages all around. I got the idea of writing a song that captured both sides of one marriage story. For any Byrds fans out there, the opening riff is borrowed from “I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better.” At the time, I had struck up a bit of a friendship with Roger McGuinn. Always loved his Rickenbacker sound. Couldn’t help myself.

When I Fell for You: The sentiment and some elements were plucked from my life, but I was more influenced by nostalgic rock songs like “Summer of ‘69” and “Cherry Bomb.” So I wrote from the perspective of young lovers who met in a small town, and then life gets in the way and they find themselves thinking back on better days.

Just Break Away: The most autobiographical song I ever wrote. When I wrote it in my late-40s, I was struggling with making sense of my life and reconciling with my father’s death when I was a kid. While I took some liberties with the facts – there was, for instance, never a “girl from years ago shopping for a dress” moment – a lot of the references come directly from growing up in Binghamton, N.Y. I did get one chance to pitch in Little League. My second pitch of the game got blasted out of the park. That was the end of my pitching career.

Pretty Smart Car: I was the technology columnist for USA Today for more than a decade, and I got to know a lot of tech journalists from other publications, including Quentin Hardy, a long-time tech editor with the Wall Street Journal, Forbes, and NY Times. We were probably bored at a tech conference and started talking about writing song lyrics together. Smart cars were a hot topic of the day, so we took off from that and wrote this song. When recording it with Tony, I felt we needed a fiddle part. Through Tony’s contacts we landed on Joe, who recorded his brilliant part on his own and sent it back.

Missing You: I always liked John Waite’s hit song, and for years I enjoyed playing a solo acoustic version that’s slower and more plaintive. I wanted to have one cover on the album and chose to do this. I love Tony’s piano playing and his understated production.

Somewhere It’s Another Day: I loved the way The Beatles played with words and terms, like “Eight Days a Week” and “Hard Day’s Night.” In a way, this song is a flip side of “Yesterday.” Instead of longing for yesterday, our heartbroken protagonist longs to get on a jet and fly to the other side of the world where it’s ANY other day – though he can’t figure out if it’s the next day or the day before.

Stop Something I Can’t Start with You: Again, here’s the Lennon-McCartney influence, playing with words and phrases. I used that idea throughout the song as a way to show the conflicting emotions of being smitten with someone but unable to act on it. “When we’re alone I find I have to leave before I stay” – that kind of thing. I wanted this to be a duet, and thought of my friend Regan Glover, who sang with me on stage a few times. Her sweet vocals take the song to whole new level.

I’m Moving On: When I first moved to New York, I got involved in a band with a female singer who had a bluesy, soulful kind of voice. She was going through a tough breakup, and I actually wrote this song for her to sing. Then she left the band. I still liked the song and thought it would be something different to put on this album. Would love to play this live with a horn section!

Full Moon: In 2020, in the middle of Covid, my daughter, who lives in England, was about to have a baby. I live in New York. I kept thinking about having a granddaughter so far away, and wrote this song as something I could sing to her. Tony’s production brings this great 1980s synth-pop sound to it, influenced by the song “Take My Breath Away.”

Born Without No Blues: Total silliness. Just wanted to write a traditional blues song with very untraditional blues song lyrics. Somehow the line “I’m sitting in a sauna with ten ugly naked guys” came out and the rest just flowed.

Love Loss Hope Desire is available on Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon or just about any platform.

April 3, 2024

The Time I Flew With Gary Hart on Aeroflot

In 1991, I unexpectedly got to be buds with one-time presidential candidate Gary Hart on an Aeroflot flight from Moscow to Latvia.

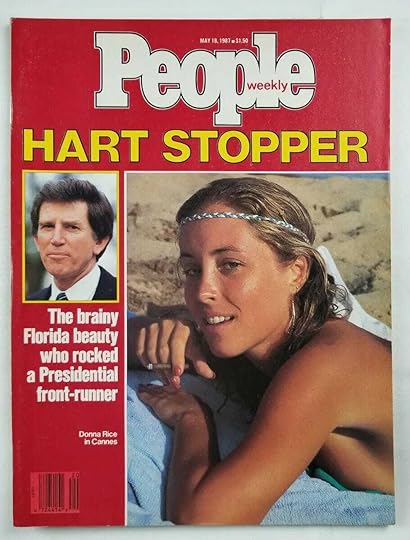

Just a few years before that, Hart, who is now 87, had a solid chance of becoming president. Charismatic and handsome, during campaign season for the 1988 election Hart was for a while the favorite to win the Democratic nomination. He got derailed by a scandal that today, after years of bathing in Trump sludge, would barely get a shrug. Journalists caught him messing around with a woman named Donna Rice, who was not his wife.

Soon after that story broke, Hart dropped out of the race, and at least from my perspective went quiet.

By 1991, I had made several trips to Moscow and to some of the countries that were escaping the old East Bloc. On this particular trip, I wanted to write some stories out of the Baltic nations – Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. First, I traveled to Moscow to do some more reporting there, and then I bought a ticket to fly from Moscow to Latvia’s capital, Riga. The only airline flying that route was the old Soviet state airline, Aeroflot.

Flying on Aeroflot in those days is where things could get weird.

As an American, I bought my ticket with dollars – which was known as “hard currency” in the old Soviet Union. The USSR’s rubles were not then an international currency – pretty much worthless outside of Soviet borders. The Soviet government and industries needed international currency – or hard currency – to buy goods from most other countries, like Germany or Japan. So whenever possible, the Soviets sought to charge foreigners in dollars, pounds, yen or anything that could be used for international trade.

Paying in hard currency won you VIP treatment. It got you into the best stores, hotels and restaurants in Moscow. (And you really didn’t want to go to the less-than-best stores, hotels or restaurants in Moscow. The drop-off was severe.) The VIP thing also applied to flying – to a point. Once I got to Moscow’s airport and found my gate, I was ushered into the “nice” gate for those paying in hard currency, while the Soviets who paid in rubles got pushed into the shitty gate.

The nice gate was about as nice as a Texarkana bus station, so I can’t imagine what the shitty gate was like – though it was certainly a lot more crowded. Most of the people taking the flight had paid in rubles. Only foreigners paid in hard currency, and not many foreigners traveled around the disintegrating USSR at the time.

So I walked into the nice gate where there were maybe a dozen people. I looked around to see if someone looked American. Most of the travelers seemed to be from somewhere in Europe. But as I gazed around, there was this one tall guy across the room, and he looked like…wait…wait…holy crap, that’s Gary friggin’ Hart!

If I’d seen him across the gate in a U.S. airport, I would’ve enjoyed the celebrity siting and left him alone. But there’s a different sensibility when you’re the only two Americans about to board an Aeroflot flight from Moscow to Riga. It was kind of like strolling around Mars and running into the only other human on the planet. So I walked over and introduced myself, and let him know I was a journalist from USA Today.

Hart seemed happy enough to meet me. We started chatting about what we were each doing there. He was, remarkably, traveling alone. Another aspect of flying Aeroflot was that there were no assigned seats, and certainly no first class – this was, after all, a communist nation. Although the hard-currency passengers got to board first and choose their seats. The reason I say Hart seemed glad to meet me is because he then asked me if I’d like to sit with him. So, I did, and we talked through most of the flight – again, mostly about why were there and what we were observing.

Why was Gary Hart in Moscow and Riga? Basically, consulting for U.S. entities that wanted to do business or make connections in these newly-opening economies. Hart had also been working on a book about that part of the world. (It didn’t get great reviews.)

After we landed, Hart gave me his card and suggested we keep in touch. We parted ways and I went to my hotel. As it turned out, my hotel was apparently the only Riga hotel Westerners would want to stay in, and when I later went to dinner there, I again ran into Hart, who was having a business dinner with a couple of Latvians.

Over the following few years, I called Hart once in a while when working on a story about Russia, or something that had to do with technology and government. He always took my calls and was helpful. He’s stayed active since then, consulting, writing, speaking and working in academia. In 2014, President Obama made him Special Envoy for Northern Ireland.

I haven’t talked to him in ages, but the internet says he now lives in Kittredge, Colo. Next time I fly through Denver, I’ll keep an eye out for him.

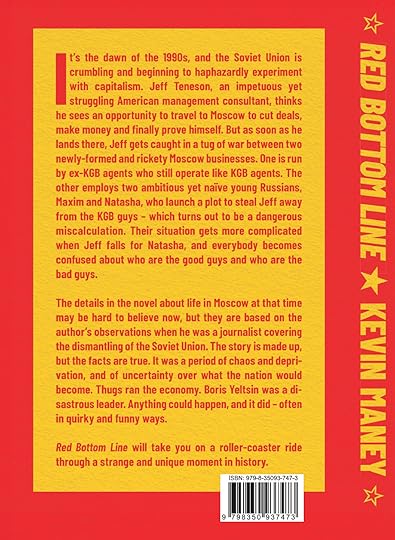

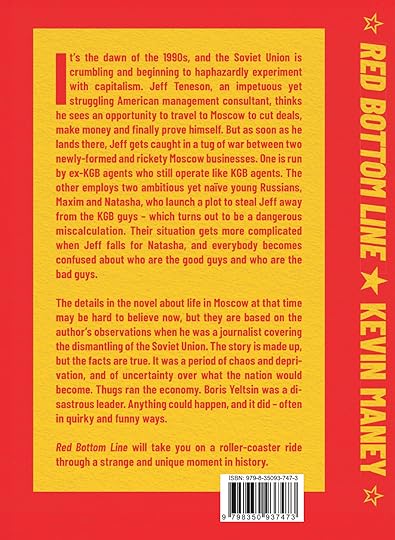

I just published a novel, Red Bottom Line, that is based on my adventures in Moscow as the USSR was breaking up.

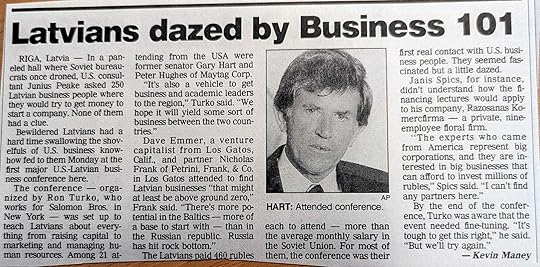

This is a short story I wrote from Riga for USA Today, appearing in October 1991. It’s not available online. I searched for some of my other stories that quoted Gary Hart but, again, USAT was lame about digitizing older stories, so nothing came up.

March 21, 2024

Is Nvidia Remaking the Movie: “Corning 2000”?

Nvidia looks like a marvel these days. The company has been around for 30 years. Now it finds itself in the right position at the right time: It dominates in the manufacture of the hyper-fast microprocessors that are exactly what’s needed for suddenly-exploding generative AI. Its stock has rocketed from $120 a share in October 2022 to around $900 a share now, giving Nvidia a market value of $2.3 trillion.

It took me a while, but I just realized that I’ve seen this movie before, up close and personal. And the previous one didn’t end well – nearly ended in disaster..

Which may be worth considering if you’re thinking about jumping on the Nvidia bandwagon.

Here’s the backstory:

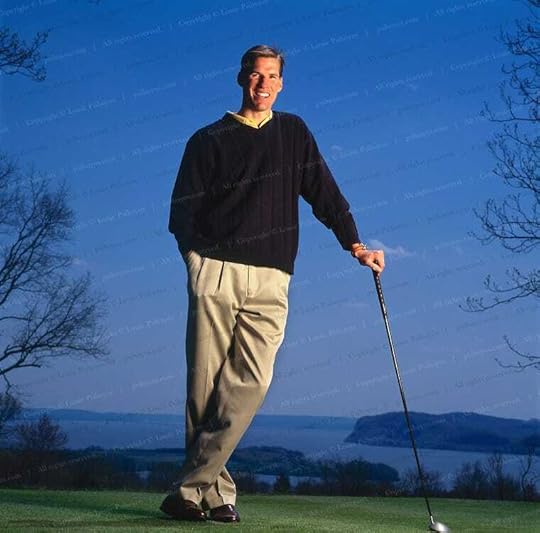

I’ve known Wendell Weeks for a long time. We first met at a telecommunications conference in 1995, where we sat next to each other at dinner and immediately hit it off. Wendell is whip-smart, deeply knowledgeable, funny – often very funny – and exceedingly tall. He was at the conference because, at the time, he was running Corning’s fiber-optic business. Corning had invented optical fiber and was by far the dominant manufacturer.

I was at the conference as a speaker because I’d just published a book, Megamedia Shakeout, about the emerging digital media boom. (I got lucky – I started the book in 1993 and it came out in April 1995, just as companies like Netscape, Yahoo and Amazon were bursting onto the scene.) Wendell and I discovered that we were the same age, had kids the same age, and had a shared love for New York State’s Finger Lakes. Wendell lived and worked in Corning, N.Y.; I grew up in Binghamton, N.Y. The Finger Lakes are near both.

So after the conference, we kept in touch, became friends, and I paid close attention to his work and career.

Wendell Weeks

Wendell WeeksOver the following few years, the internet boomed. The supercharged atmosphere of the late-1990s was not unlike what’s going on today with AI. Every company had to consider what the internet would mean to it. Capital flooded into dot-com startups and those companies rushed to scale as fast as they could. Investors and business leaders understood that moving around all of the anticipated swell of internet data traffic would require massive new telecommunications infrastructure. Capital then flooded into telecom upstarts like WorldCom, Enron and Level 3, which meant that those companies had insane amounts of money to spend as they all sprinted to beat the others at building out their networks.

A lot of the money that poured into telecom companies found its way to Corning. Corning’s optical fiber systems were the core element that could make the internet boom go. No high-speed data networks, no internet boom. Most every company that wanted to compete in carrying internet traffic had to turn to Corning.

Corning was founded in 1851. It once made those Pyrex coffee pots and Corningware bowls your mom or grandmother probably had in their kitchens. It invented the glass for Thomas Edison’s lightbulbs and the glass for early TV sets. In 1970, Corning researchers invented the first low-loss optical fiber, and the company built fiber into a solid business serving phone companies like AT&T and MCI. Still, in the early 1990s, fiber was just one Corning product among many. Corning’s stock rose steadily but not spectacularly, from around $2.50 in 1984 to about $9 in early 1996.

As the internet took flight, Wendell went to Corning’s CEO at the time, Jamie Houghton, and pushed for more resources for the fiber division that Wendell ran. Corning’s management decided to lean all the way in on fiber. While the company kept making glass for all sorts of other industrial uses, it pushed almost all its poker-table chips over to Wendell’s bet on fiber. In February 2000, for instance, Corning announced it would spend $750 million to expand its optical fiber manufacturing capacity by more than 50 percent.

For a while, the strategy looked brilliant. Demand from the Enrons and WorldComs and Level 3s went crazy. They had blank checks from investors to spend, and so they did. Wall Street noticed Corning’s opportunity. This 140-year-old company suddenly had the right product and a dominant market position at the exact right time. In August 1998, Corning’s stock was still hovering around $9 a share. Two years later, it was $100.

But September 2000 turned out to be the peak. The dot-com bubble was in the process of bursting. The Enrons and WorldComs and Level 3s had far overbuilt and withered as demand didn’t catch up. What once looked like precious and scarce fiber optic bandwidth turned into a glut. Enron got caught in financial scandals and collapsed in 2001. WorldCom filed for bankruptcy in 2002.

Wendell had to watch as the hungry demand for Corning’s fiber went poof. By August 2002, Corning’s stock had fallen to under $2. The whole of Corning – one of America’s great industrial companies – nearly went under. The bet on fiber almost killed it.

In 2007, after Wendell was named CEO of Corning (more on that twist in a minute), I interviewed him in front of an audience at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. The transcript was edited into a story for USA Today. I asked him what he learned from the scary free-fall.

“Wall Street had given (these telecom companies) around over half a trillion dollars, and so when people show up with hundreds of millions of dollars to buy your product, you tend to believe them,” Wendell said. “Our big lesson learned was, for one, it’s not enough just to be the best at what you do. You also have to understand your customers’ business model and your customers’ customers’ business model. We were risking more than money. We were risking significant dislocation of people’s lives. That was my biggest error – not understanding that. I wasn’t alone in not understanding that perhaps Enron’s broadband strategy was ill-conceived. But if I had it all to do over again, we would have tried to understand that better.”

I’m not saying that a similar fate awaits Nvidia, but there are elements of Nvidia’s story that seem to echo back to Corning’s.

As Wendell alluded to, hardly anybody in the late-1990s thought the demand for fiber would dive. Some analysts in 2000 were still predicting that fiber demand would be nearly infinite. (It may be – but over decades, not a few years.) We can get blinded by what’s happening in the moment and think it will go on forever. A lot of smart people today think AI could go through a 1990s-2000s internet-like cycle of boom, bust and rebirth as this decade unfolds. Nvidia might navigate that well. But, like Corning back then, Nvidia has placed most of its chips (ha – computer chips) on the AI bet.

At least the Corning story avoided a catastrophic ending, for either Wendell or the company. Houghton, an under-appreciated terrific CEO, didn’t fire or demote Weeks. Instead of knee-jerk reacting, Houghton promoted Weeks to chief operating officer. As Weeks told me, Houghton called him into his office and said, literally, “You helped fuck this up. You help fix it.”

Houghton worked with Wendell to stabilize the fiber division and the whole company. By early 2005, Corning stock was up to around $11. In April 2005, Houghton stepped down and made Wendell CEO. Not only had Wendell helped fix what he helped fuck up, he learned valuable lessons about how to make sure the same thing never happens again. He’s still CEO and Corning stock is around $33.

In the decades since, Corning has reinvented itself over and over, which has always been the key to its longevity. It developed the glass for Apple’s first iPhone and dominates the market for smartphone glass. It makes the glass for much of the world’s flat-screen TVs. It makes specialized glass for vaccine vials. And it’s still a major player in fiber optics – a product that is still in high demand.

We’ll see if Nvidia can play that kind of long game.

USA Today has long been lame about digitizing its past stories, so the original is not online. However, newspapers around the country often ran my stories by getting them through Gannett News Service. I found a version on Newspapers.com, as it was published in 2007 in The Daily Spectrum in St. George, Utah.

February 21, 2024

A Visit With a Flying Car That Never Worked

Very, very soon, we’re all going to have flying cars. Which is also what Paul Moller told me in 1991 when I went to see the Skycar M400 he was building in Davis, Calif.

From what I’ve read these days, there are a number of legit flying cars in development now, some with the backing of car companies like Hyundai and Toyota and one, from Chinese company XPeng AeroHT, that wowed attendees of the Consumer Electronics Show in January and is about to go into full-scale production. Chaos in the skies can’t be far behind.

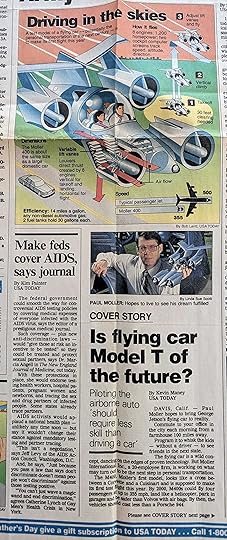

But in 1991, there was pretty much one place to go to see an actual, maybe-it-will-eventually-work flying car, and that was in Moller’s shop. Here’s what I wrote for USA Today in May of 1991:

“The M400, Moller’s first model, looks like a cross between a Corvette and a Cuisinart and is supposed to make its first test flight this year. By 2000, M400s could fly four passengers at up to 355 miles MPH, land like a helicopter, park in garages and be safer than Volvos with air bags. By then, the vehicles should cost less than a Porsche 944.”

I also noted that Michael Jackson called Moller to ask if he could buy one.

But, yeah, none of that actually worked out.

Moller, who is now 87 and lives in Canada (where he was born), was an odd character who obsessively worked on flying cars for decades, burned through who-knows-how-much investor money, and never made a viable model. By the time I interviewed him in 1991, he’d been at it for 25 years. Then Moller got sued by the Securities and Exchange Commission for defrauding investors. Moller settled without admitting guilt. By 2009, his company was $43 million in the hole. And still no Skycar.

I have vague memories of going to Davis and spending time with Moller. He seemed socially awkward, savant-like brilliant and not quite living in the real world. Since the idea of a real flying car – not just the cartoon flying cars in The Jetsons – was new to most people, I spent the bulk of the story describing how it would work and how we’d use one. When I noted it would eventually fly on autopilot, I wrote that it would be armed with “global positioning satellite technology”…and then had to explain what it was.

When I wrote the story, the most fascinating part of it was just the idea that a flying car might actually come to pass. But looking back, I think the more fascinating part really was Moller.

He told me he was, at the time, 54 or 55 – “I stopped keeping track of my age after 21.” He built a helicopter when he was 15, learned welding so he could build aircraft from scratch, and eventually became an aeronautical engineering professor at the University of California at Davis – which is why he was in Davis, about 15 miles west of Sacramento.

As he worked on his flying car, he kind of accidentally developed the Supertrapp Muffler, started a company to sell it for race cars, and sold the company in 1988 for $3 million. Then he developed the industrial park around his garage in Davis and made $5 million off that – plowing everything he made back into the Skycar. The Skycar ate his life. “From the beginning, it grabbed me and I wanted to finish it, and I wanted to own it,” Moller told me.

Three years later, I caught up with him again. He got in touch because he said he was a few months away from a first flight in the Skycar, which he planned to take himself. But that never came to pass. Soon to come were the SEC suit and other troubles. A Wikipedia entry about Moller says, “In April 2009, the National Post characterized the Moller M400 Skycar as a 'failure', and described the Moller company as ‘no longer believable enough to gain investors.’”

Writing all this just kind of makes me feel bad. What must it feel like to devote your whole life to something that essentially fails to materialize?

In category design, we talk about the concept of the adjacent possible. New inventions take hold when they are just beyond the possible – just stretching the technologies we already have and use. Yet they are not so far into the impossible that the technology won’t work and the public won’t get it.

Sometimes companies with a grand vision get too far out into the impossible and never catch on before they run out of money. Moller was clearly way, way, way out beyond the adjacent possible in 1991.

But the latest news about flying cars suggests that maybe…just maybe…the technology is near hitting the adjacent possible. And if that’s true, within a few years all those people who thought they were so cool because they bought the first Teslas – they’ll be lining up to buzz overhead in some kind of cross between a Corvette and a Cuisinart.

Here is the story as it appeared in USA Today on May 23, 1991. It is not available online.

February 14, 2024

Excerpt: Red Bottom Line

This is the opening of my novel Red Bottom Line, which is being released as an ebook on Feb 15 and print book on March 15.

The stewardess bent low and held a tray of typical Aeroflot drinks in front of the passengers sitting in the three seats on the left side of row. The liquids in the plastic glasses came in three colors: neon yellow, brownish orange and pink. The jet bounced through some turbulence and all the drinks rolled around in their glasses like heavy motor oil.

The man in the aisle seat and the woman in the middle seat next to him – the only two Americans on board the February 12, 1977, flight from Moscow to Kiev – looked at each other and made faces.

“Care for another fine Russian refreshment made entirely from materials not found in nature?” the man said to his traveling companion.

“Oh, why, I’d love to, but I’m trying to watch my weight. I’ll pass.”

The stewardess didn’t budge. She looked as if she hadn’t smiled since the last time she played jump rope.

“Nyet,“ the American woman said, shaking her head for emphasis.

The Russian in the window seat reached across the two Americans and chose one of the orange concoctions. The stewardess, still stone-faced, moved on to the next aisle. The American man nudged his friend.

“Barbara, ask him if he’d rather have a Pepsi.”

“No way! You ask him.”

“Me? I don’t know Russian. You can speak it a little at least. You’ve been over here a lot longer than I have. Just tell him, ‘My friend Will here wants to know if you’d like a Pepsi instead of that glass of ceiling paint.’“

Barbara Roselle giggled and put her hand on Will’s. He’d been liking his Soviet assignment for PepsiCo far too much, she thought. He went around handing out bottles of soda as if they were magic genie lamps, apparently figuring that if he could stay here long enough and hand out enough bottles of Pepsi, he could single-handedly open a market to Western products that had been closed for three decades. Barbara, who had four years in the U.S.S.R. with Occidental Petroleum under her belt, wished Will were right, but knew he wasn’t.

“All right, I’ll ask him,” Barbara said, smiling. “But this is absolutely the last time, OK?“

“Mmmmmaybe.“

She thought a minute to get the words straight, then turned to the man in the window seat, who had polished off half of his glass of orange drink. Quietly, not wanting to draw the attention of any other passengers, she said, “Prostite, tovarishch, ne hotite li Pepsi-kolu?” Excuse me, but would you like a Pepsi Cola, comrade?”

The man looked at her closely. It had been obvious to him from the moment they all took their seats that Barbara and Pete were Americans. Both were in their early thirties and wearing Western business clothes. The blue and red in Barbara’s dress were colors that East Bloc garment factories never churned out. Anything brighter than dull mustard was rarely available in any Soviet shop. And Will’s gray wool suit stood out against the baggy linen and polyester outfits that draped even high Soviet officials. The Russian in the aisle seat had stayed scrunched into his corner, ignoring those two from a nation that was supposed to be his enemy. But Barbara’s offer touched a chord.

“Pepsi?” the man said.

“Da, Pepsi.“

The man smiled, showing off a wide mouth of mostly rotted-out teeth. “Spasibo.”

“All right, Will, you’ve got another customer.”

“Hey, works every time,“ Will said as he fished a five-inch-tall cola bottle out of his carry-on bag, which he’d left in the aisle the way everybody else did.

“Pozhalsta!” he said to the man as he handed him the bottle.

The man showed Barbara and Will one more glimpse of that dental work. The Russian patted Barbara’s hand, which was sitting on their shared armrest. Then the two Americans watched as the man — with only some effort — pulled the cap off the bottle with his bare hand.

“That was not a twist-off,” Will said.

Barbara laughed and put her head on Will’s shoulder.

“You know, I can’t tell you how happy I am that I found you here,” she said. “I’ve had more fun with you in the past couple of months than in the entire time I’ve been here so far.” She leaned closer to his ear. “Of course, it helps that it’s the only sex I’ve had in the entire time I’ve been here.”

“Hold it! You told me it was the best sex you’ve had here.”

“Well, I didn’t lie. It is the best. It’s also the only. But I know it’s pretty damn good.” Barbara discreetly tickled Will’s crotch.

“Yeah? How good?”

“Good enough that I can’t stop thinking about it?“

“I have an idea.“

“What’s that?”

“You ever try getting it on in a Russian jet?”

“Barbara nuzzled close to Will. “You can’t be serious,“ she said. “Can you? If they catch us they’ll probably throw us out the hatch.“

“Well, we’ll just have to make sure they don’t catch us. I’ll go first. I’ll go to the bathroom in the front, on our side of the plane. Give me a few minutes and then follow me. Just give the door a light knock and I’ll let you in. Nobody will have any idea. What do you say?”

“Mmmmm — I don’t know. Somebody could see us — or they’ll see us come out. Don’t you think this could be dangerous?”

“Dangerous? Not a chance. Embarrassing, at worst. C’mon. Just follow me in a few minutes. OK?“

“I can’t believe I’m saying this, but all right.”

Will pushed himself out of his seat and headed toward the front of the plane, which looked to him pretty much like most passenger jets in the West — one long tube with three seats on each side of a narrow aisle. Although, thanks to communism’s ideals of equality for all, there certainly was no first-class section. Will was walking toward the bathroom that, in the U.S., would likely be reserved for first class passengers.

The Russian in the window seat pointed toward the front of the plane and started explaining something to Barbara. She tried to pick up the web of Russian syntax and words, sort them out, figure out what he was saying. Something about a Communist Party member.

“Nomenklatura?” she asked.

“Da. Da.” He kept talking. She caught on. A candidate for the Soviet Politburo was on the flight, and he was sitting in the front seats. That’s where they’d often sit so security agents could easily seal off that section to protect their man. Will would probably get turned back before he got anywhere near the bathroom.

The Russian’s voice dropped a notch as he leaned toward Barbara. He explained that the candidate they’re riding with is a reformer, someone who wants the U.S.S.R. to be better friends with the Americans. The candidate, he said, has many enemies.

Barbara and the man heard a commotion in front, but they couldn’t see past a divider a few seats up. Then Will came bounding back toward them.

“Holy shit! Some clown up there nearly knocked me down.”

“You OK?“

“Yeah. He jumped up and gave me a hard shove and started babbling something in Russian. I gave him a shove back and I thought I was going to get killed. About five other Russian guys jumped up and came toward me. I don’t know what the hell is going on.”

Barbara giggled. “You sure know how to show a girl a good time,” she said. “Our friend here was just telling me that there’s some party bigwig up there. A Politburo candidate or something. Sorry about that.”

Will looked at the Russian, who just shrugged and took another gulp from his Pepsi bottle.

“Well, no sense in letting the Communist Party get in the way of some good old American fun, right?”

“I don’t know, maybe it’s not a good idea now. What do you say we wait?”

Will leaned down and whispered, “That would take all the adventure out of it. Same plan. Back bathroom. Bye.”

He took off down the aisle. Barbara stayed in her seat, feeling nervous. She shared a smile with the Russian. She looked around to see if anyone was watching — if anyone could tell what they planned. No one seemed to be paying attention. She glanced at her watch. It was 9 p.m. Dark outside. They were just about in the middle of the route from Moscow to Kiev, over some wasteland that was once peasant farms. Barbara took a long breath. She started sliding out of her seat. She said in English, “I think I have to go, too.” The Russian just nodded and smiled.

Both bathrooms were occupied. Now which one did he say? The one on the right or the one on the left? She knocked on one. Will called out in a sing-song voice, “Who is it?”

“Someone who’s going to kill you in about two seconds.”

The door opened a crack. “In that case, we don’t want any,” Will said.

“C’mon! I don’t want to fool around.”

Will flung open the door, grabbed Barbara’s arm and pulled her inside. “I thought that was exactly what you came back here for.“

“You are a complete nut case. I should’ve left you sitting there by yourself in the National hotel dining room, trying to figure out whether you really wanted to eat that gray piece of fish on your plate.”

“I know. And I probably would have had to spend the rest of my time in Russia living on borscht and ruining all my business meetings because I’d be farting all the time. You’re my savior.”

Will reached around Barbara and pushed the bolt to lock the door. Their bodies were pressed close together in the tiny confines — no bigger than a shower stall yet packed with a toilet, sink and cabinet. The plastic door of the cabinet was set up to dispense paper towels, soap, tissues and toilet paper, but each hole was a yawning disappointment. Not a single scrap of paper or piece of soap were in any of them. Half of the white fluorescent light over the sink was burnt out. The mirror was coated with a dull, dusty grease.

Will brushed Barbara’s hair back and framed her face in his hands.

“It really stinks in here,” Barbara said.

“Wow, do you know how to be romantic. You just say the right few words, and — BANG! — the atmosphere turns electric.”

“I’m sorry. I’ll hold my breath or something. Really.“ She pulled Will’s face to hers and kissed him deeply.

Her mind drifted far away from that little flying cesspool. She was in Will’s arms. That was all that counted. To an American, an assignment in the Soviet Union in that day was a ticket to frustration. The creature comforts were only a part of it. Any semblance of Western style was completely missing. The telephones didn’t work most of the time. Using the make-up that was available was about like smearing colored paste on your face. Fruits and vegetables were unheard of, despite any pull you might have with party officials. On the streets of Moscow, it never mattered whether it was one of those bitter winter days when even your breath seemed to freeze in mid-air, or an easy summer morning when the few trees and flowers around the concrete city bloomed like weeds between the cracks of a sidewalk. Either way, Muscovites would turn up their collars and avert their eyes when an American walked by. They wouldn’t talk. They wouldn’t smile. Some obviously thought you were an invader, a person with dangerous ideas, someone who could only be in Moscow to try to undo whatever good the Communist Party had achieved. Others, their faces said, “I would like to know you, but I cannot.” They were afraid. And it not only made business hard, it made life hard. If she had known all of that before she ever agreed to work on Occi’s Soviet business, she probably would have never taken the assignment. But at the time it sounded romantic. Grand Russia. Exotic Russia. The Kremlin. The onion-domed cathedrals. The caviar. It all turned to hell.

Until Will. He was kissing her neck as one hand unhooked the buttons on the top part of her dress. A smelly, filthy bathroom on a Soviet jet staffed by stewardesses who radiated all the warmth of a family of wart hogs was suddenly the most romantic place she’d been in all of the Soviet Union. She loosened Will’s tie, opened his shirt and ran her hands up and down his bare chest. Will unsnapped her bra and cupped her breasts in his hands. His mouth worked its way down from her neck.

“Will,“ Barbara said, almost breathless, “how are we going to do this?”

He pulled the skirt of her dress up over her hips. “Here, hold this,“ he said. He slipped his hands into her pantyhose and slid them down to her ankles. He stood, lifted Barbara and set her on the small counter next to the sink. The pantyhose dangled from her ankles. He pulled them off, then let down his pants and shorts. Barbara pulled him in close and wrapped her legs around him. They kissed again.

The bathroom was filled with heat and motion. Barbara and Will could not contain themselves. They forgot that anyone may be outside. They moaned. They said each other’s names. Will bumped into the door. Barbara kicked the toilet seat. They both crashed their shoulders into the empty front cabinet panel.

It fell to the floor with a great clunk. They stopped.

Barbara giggled.

“Holy fucking shit,“ Will said, gawking at the hole in the wall that the cabinet had covered.

“Oh, now you’re going to get worried,“ Barbara said playfully.

Will had gone completely white. “Barbara, don’t fucking move.”

“Will, what’s the matter? You have me scared.”

“Look in there.“

She followed Will’s eyes, which hadn’t left the hole in the wall. Inside was something white with wires coiled around it.

“What is it?“ she asked.

He looked hard at the woman in front of him. “Barbara, I think it’s a bomb.”

“Oh God, Will.“

The Russian holding a Pepsi in the window seat, the Politburo candidate and his guards and the others in the plane only heard a pop, much like the top coming off the cola bottle. It was the last thing they heard. The tail section whooshed away and the rest of the plane broke up. The metal, the luggage and the people were scattered across the forests and farmlands of the Soviet countryside.

February 1, 2024

The Story Behind "Red Bottom Line"

After publishing nine non-fiction books (and writing one that got away), I’m finally publishing a novel…that I started thirty years ago.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, I covered the breakup of the Soviet Union for USA Today, traveling to the region often, interviewing people, visiting semi-legal startups, even being on hand for the opening of the first Moscow McDonald’s. It was a crazy, fascinating, we’ll-never-see-this-again slice of time when a superpower nation fell apart and tried to adopt an entirely new system.

I wanted to use it as the setting for a novel – a funny, quirky thriller. I started writing it in 1991, just after my daughter Alison was born.

The finished book is titled Red Bottom Line. The plot revolves around Jeff, an impetuous young American management consultant who thinks he sees an opportunity to make easy money in the just-opened economy in Russia. As soon as he lands in Moscow, he gets caught between two newly-formed and rickety Moscow businesses – one run by ex-KGB agents who still operate like KGB agents, and another represented by two ambitious but naïve young Russians, Maxim and Natasha.

In a reflection of stuff that really happened, Maxim and Natasha cook up a plot to steal Jeff away from the KGB guys – which turns out to be a dangerous miscalculation. Along the way, Jeff falls for Natasha, gets schooled about Russia, and grows up…a little.

Looking back now, the story is a deep-dive into a time that helps explain the rise of Vladimir Putin and his autocratic rule. The details in the novel about life in Moscow around that time may be hard to believe, but they are all things that I personally witnessed or knew about. The story is made up, but the facts are true. It was a period of chaos and deprivation, and of confusion over what the nation would become. Thugs ran the economy. Boris Yeltsin was a disastrous leader. No wonder Russians welcomed a strongman who said he could “fix” everything.

I wrote Red Bottom Line before I’d written any books. I didn’t have an agent. Didn’t know anything about publishing. I sent it cold to a few editors and agents, and none even responded. So, I gave up, printed out a copy, and put the book in a plastic bin that moved with me from house to house for three decades.

Then, a couple of years ago, Alison asked me if she could read the book. But first I had to find it. I poked around my storage bin in the Bronx, and found the printout secured in Tupperware.

I told Alison that I wanted to read it first. I was prepared to find it embarrassing, in which case I was just going to throw the whole thing out. I picked up the pages and started reading. It was as if I was reading a book written by someone else – I remembered so little of it. And to my surprise, I thought it was really good. I felt proud of my young self the writer, and frustrated with my young self who so easily gave up on publishing the work.

I sent it to Alison, who is very well-read and is a journalist and editor. Alison really enjoyed it, but she sent me notes on how to make it better. Her suggestions were good ones, and I took some time to edit the book – but it only needed some light touches.

To test whether I was delusional, I gave the edited version to a handful of smart, worldly friends who I knew would tell me the truth about the book. The reviews that came back were positive, and my friends encouraged me to publish the book. (Mo Rocca, of the Mobituaries podcast and CBS Sunday Morning, even agreed to provide an endorsement.)

So, here we are. Red Bottom Line is two weeks from being released as an e-book. It comes out in print March 15. Amazon is taking pre-orders. The book will also be available on pretty much every book-selling platform.

I have a couple of requests. First, if you find this at all interesting, check out the book on Amazon. Just getting some traffic to the page will tell Amazon to stock more of the books and boost it in its recommendation engine.

Even better, if you’re really interested, please pre-order a print version. That will do even more to convince Amazon to support the book.

And finally, if you read and enjoy Red Bottom Line, please leave a review. That would help a lot.

Oh, and just so I can dream, if you then have some ideas for who might play Jeff, Natasha and Maxim in the movie, I’d love to see it in comments.

(Cover by https://www.linkedin.com/in/jacontre/)

January 10, 2024

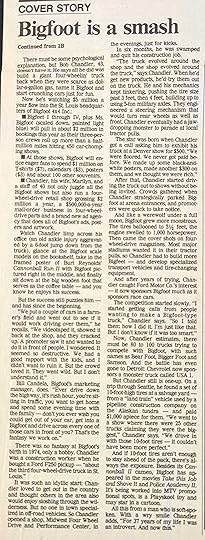

Bigfoot and Me

There I was watching a recent New Jersey Devils home hockey game on TV when a commercial popped up for an event that I never knew existed – a Monster Jam, which would take place in that very same arena in a few weeks.

And I thought, huh, I actually rode in a monster truck for a show at the Missouri State Fair in 1985 while I was working on a story about the guy who invented the monster truck, Bob Chandler.

Bob drove, of course. I was white-knuckling it in the passenger seat. But after the show, once I climbed ten feet down out of the truck, kids rushed up and asked for my autograph. Turns out just riding in a monster truck can turn you into somebody.

In the summer of 1985 – my first year as a reporter at USA Today – I was getting a reputation for quirky business stories (see: Zamboni). My editor came by and suggested I do a feature about Bigfoot. I knew nothing of said Bigfoot, but with a little research found out that outside of St. Louis, Bob Chandler had built what is recognized as the first monster truck, which he named Bigfoot. And the truck was becoming a celebrity. It had even made an appearance in Burt Reynolds’ Cannonball Run II.

So off I went to Missouri to visit the headquarters of Bigfoot 4X4 Inc., which had become a $5 million a year operation with 40 employees. I remember interviewing Chandler as we sat around a coffee table that was a big wooden foot. And he told me that the whole Bigfoot phenomenon was an accident, and that he still didn’t understand its appeal.

Here’s the backstory: In 1974, Chandler was a construction worker who bought a Ford F250 four-wheel drive pickup truck. He got into off-roading in his truck and figured others would like it, too. But there weren’t any shops in town catering to that pastime. So he opened one, Midwest Four Wheel Drive and Performance Center.

Chandler and his mechanics liked tinkering, so they kept putting bigger tires on the F250 and adding steering systems and axles that would let the truck drive over bigger things. Eventually they found tires that were ten feet high and put them on the truck.

Here’s what Chandler told me happened next: “We put a couple of cars in a farmer’s field and went out to see if it would work driving over them. We videotaped it, showed it back at the shop, and they cracked up. A promoter saw it and wanted to do it in front of people. I wondered. It seemed so destructive. We had a good rapport with the kids, and I didn’t want to ruin it. But the crowd loved it. They went wild. But I don’t understand it.”

By the time I met Chandler, the business had four Bigfoot trucks and a Ms. Bigfoot (scaled down, painted light blue). Between them, they were doing 450 shows a year.

Chandler thought I should experience a show. I didn’t realize he meant I should experience one from inside the truck. Here’s how I described it in the story:

“Here he comes,” wails an announcer, “the original monnnnster trrrruck, Biiiiigfoooooot!” The star takes its cue, roars to life and rips into three junk cars bunched under the spotlight. The front end of the 14,000-pound Ford truck pops into the air, wheels momentarily spinning free. The modified monster then slams down on one rooftop. Glass shatters, the car’s roof collapses, and Bigfoot bounces over all three cars, turns around and heads back for more.

This time the driver gets more height and the truck pounds down like a wrecking ball. The arm-thick treads chew up the cars as Bigfoot powers across the pile of junk and rolls to a halt. The driver opens the door and waves to a cheering, rollicking crowd.

Yes, I was inside for all of that.

Then with the crowd cheering, I jumped out, a newly-birthed star, happy that none of my limbs had been shaken off of my body.

Nearly four decades later, I realize there is something else that Chandler did that I didn’t fully appreciate at the time: Chandler created a market category called monster trucks. As Bigfoot got popular, others wanted to build similar trucks. They’d call Chandler to get some insight. “So I told them how I did it,” he told me in 1985. “I’m just like that. But I don’t know if it was too smart.”

Actually, if I put on my category design hat, I’d say it was really smart. Helping form a market category legitimized Bigfoot. The act became more than an oddity – it turned into a new form of entertainment. If Chandler had held tight to his secrets, there might not be Monster Jams or so many other monster truck shows filling big-city arenas today.

Bigfoot 4X4 is now a huge business. It does shows all over the world – even the O2 Arena in London. It has a team of 12 drivers, including Chandler, now in his eighties, and sells clothing, toys, posters and coffee mugs. Creating a far bigger pie benefited Chandler and Bigfoot.

As a footnote, Bigfoot does not appear in the Monster Jam series. Apparently there was a dispute with the organizers in 1998 over licensing of video footage, and Bigfoot stomped out, never to return.

Which saves me from having any reason to buy a ticket to the upcoming show in Newark. For one thing, I’ve been spoiled. If I’m not going to actually be in a monster truck show, why bother? And for another thing, it’s not really my style. I drive a Mini Cooper.

The Bigfoot story in USA Today is not available online. Here are images of the story as it appeared on September 10, 1985.

January 4, 2024

That Time When Corporate CEOs Wanted to Run Dot-com Startups

You know what doesn’t happen anymore? High-ranking Fortune 500 executives don’t leave their companies to take a chance on running early-stage or challenged tech startups.

But a few decades ago, it was a thing, and much of it was powered by a headhunter named David Beirne…who I occasionally had lunch with and wrote about back in the nineties.

You could say that John Sculley was the OG of these corporate-leaping executives. Except that when he ditched the presidency of Pepsi to join Apple in 1983, Apple was neither early stage nor particularly troubled. One year after Sculley joined Apple, the company unveiled the Macintosh, vaulting Apple into legendary status.

Still, Sculley set a precedent. If he’d stayed at Pepsi, he probably would’ve become just another suit-wearing corporate CEO. His gig at Apple made him famous – even moreso after he forced out Steve Jobs in 1985. Certainly, other corporate executives noticed. Sculley, for a while at least, seemed to be having a lot more fun than they were while making a lot more money.

Yet the big trend didn’t catch hold until the arrival of the dot-com boom in the mid-1990s. Beirne helped set the trend in motion when he recruited Jim Barksdale to be CEO of Netscape, convincing Barksdale to leave his position as the No. 2 executive at wireless giant McCaw Cellular (later AT&T Wireless). Barksdale helped turn Marc Andreessen’s Mosaic web browser into a real business (although, as was common in the dot-com era, not one with profits), and took it public in 1995. Barksdale’s shares were instantly worth $420 million.

Then it started happening over and over. Beirne recruited William Razzouk out of Federal Express to be COO of AOL. He got Alex Mandl to quit as president of AT&T to become CEO of telecom upstart Teligent. He convinced Frank Ingari to leave established Lotus Development (maker of Lotus 1-2-3, a super-successful computer spreadsheet that was put out to pasture in 2013) to run a company called Shiva. Then he persuaded Jim Manzi, who was CEO of Lotus and sold that company to IBM, to become CEO of something called Industry.net.

All of which should give you a hint about why these corporate-to-startup leaps don’t happen much anymore: The companies mentioned above spiraled downward once the dot-com bubble burst in 2000. What turned out great for Sculley and Barksdale mostly turned sour for the rest of the batch. Mandl, who died in 2022, even had to repay a $12 million loan he got from Teligent.

The through-line of this story, though, is Beirne. Here’s how I described him in 1996, soon after he moved Manzi to Industry.net.

He’s a “Wizard of Oz” tornado, plucking people out of Kansas and dropping them into a strange land, a.k.a. the Internet industry. He is audacious. He is tall. He’s got about 1 million frequent-flier miles on United. He runs on two speeds: fast and blur.

David Beirne

David BeirneBeirne was 32 at the time. He’d founded his search firm, Ramsey-Beirne, nine years earlier. As the dot-com craziness took hold, he saw an opportunity to create a unique kind of firm, focused on these high-profile recruitments from corporate America to dot-com land.

What happened to Beirne? In 1997, he joined Benchmark, one of the top venture capital firms. He left Benchmark in 2007 and now has his own business, X10 Capital, which does…something with pro athletes and investing. Check out the web site and see if you can figure out what X10 does.

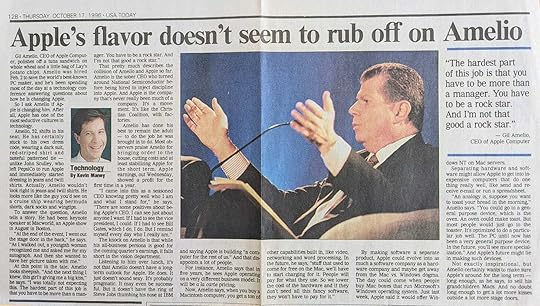

Oh, and there was one more executive leap that ended up highlighting the cultural gap between big corporations and tech companies. At the start of the 1990s, Gil Amelio was CEO of chipmaking giant National Semiconductor. In 1996, he did a Sculley, quitting to become CEO of Apple. (This was not Beirne’s doing, btw.)

It was a terrible match. I sat down to interview Amelio at a tech conference in the fall of 1996. He showed up in a suit and tie, looking completely out of place among the dressed-down Silicon Valley types. At least Sculley ditched the formal wear for jeans. Though, as I wrote, “Amelio wouldn’t look right in jeans and twill shirts. He looks more like the guy you’d see on a cruise ship wearing Bermuda shorts, dark socks and wingtips.” I quoted him in the column saying, “The hardest part of this job is that you have to be more than a manager. You have to be a rock star. And I’m not that good a rock star.”

Amelio brought some business discipline to Apple, and he gets credit for buying Steve Jobs’ NeXT Computer, which brought Jobs back to Apple in February 1997. Then, in July of that year, Jobs got the board to boot out Amelio.

Any big Fortune 500 execs want to join a startup now?

—

My original USA Today column about David Beirne is not available online. However, my columns often ran in other Gannett newspapers, so below is a clip of it from The Jackson Sun in Jackson, Tenn. It ran on February 11, 1996.

My USA Today column about Gil Amelio is also not available online, but I have the original clipping, from October 17, 1996. I pasted an image below.

December 15, 2023

Things Will Turn Out Better Than You Think

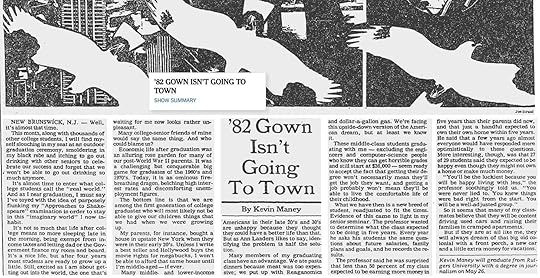

In 1982, near the end of my senior year in college, I had an enormous breakthrough as an aspiring journalist: I got an op-ed published in The New York Times. It was headlined: ’82 Gown Isn’t Going to Town.

Looking back with perspective on that essay now, I can report three takeaways:

- I was a whiner.

- People who pout about the economy today are whiners.

- Things are likely to turn out better than you think.

First of all, things were actually really bad in 1982. The Fed’s rate had hit a high of 19% in 1981, and had fallen to 14% about the time I was graduating in June 1982. A 30-year mortgage rate for a house was about 16%.

Compare that to today. In late December the Fed held rates at around 5.5%. You can get a mortgage for around 7.5%.

Unemployment in late 1982 was more than 10%, higher than any time after World War II. Today’s unemployment rate is 3.7%. Inflation had hit a high of 14.6% in 1980 and by 1982 had come down to 6.2%. Today it’s about 3.2%.

So, yeah, things looked bleak in 1982. In the Times essay, I wrote that I was graduating into a rotten economy, and that hardly any of us twenty-somethings were ever going to live as well as our parents’ generation. I got the idea for writing it after one of my professors conducted an informal poll in class. Here’s how I described it:

The professor wanted to determine what the class expected to be doing in five years. Every year he asks his students the same questions about future salaries, family plans and goals, and he records the results.

The professor said he was surprised that less than 50 percent of my class expected to be earning more money in five years than their parents did now, and that just a handful expected to own their own home within five years. He said that a few years ago almost everyone would have responded more optimistically to these questions. More interesting, though, was that 27 of 29 students said they expected to be happy even though they might not own a home or make much money. ''You'll be the luckiest because you will be happy living with less,'' the professor soothingly told us. ''You were never lied to. You knew things were bad right from the start. You will be a well-adjusted group.''

(Reading that again, I realize that telling us we’d be OK because we knew things were terrible was kind of an asshole-ish thing to do.)

I spent the whole essay whimpering about my generation’s misfortune. “The bottom line is that we are among the first generation of college graduates who will most likely not be able to give our children things that we had when we were growing up,” I wrote.

So, you probably know how this turned out. I was insanely off the mark.

By the second half of the ‘80s, interest rates, inflation and unemployment were dropping like a rock. The stock market was on fire, creating the impetus for movies like Wall Street and bestselling books like Michael Lewis’ Liar’s Poker.

In my personal life, my whiny 1982 self got a newspaper job, rapidly advanced as the economy boosted the news business, and got hired by USA Today in 1985 (giving me a couple years of experience before writing a bunch of breaking cover stories about the giant crash of the overheated stock market in 1987). By 1987, I had bought my first house and gotten married. A decade later, I had two young kids and we were living in a much bigger house than the one I grew up in.

Overall, in the past 40 years or so, total family wealth in the U.S. has risen from about $38 trillion, adjusted for inflation, to more than $140 trillion. The S&P 500 index rose about 2,800% from 1983 to 2023. Widening wealth gaps have meant that a bigger chunk of the population hasn’t benefited nearly as much as the top 10%, but in general, most everyone’s career prospects and standards of living are far better today than when I graduated.

But, of course, people don’t measure their current state against 1982, especially since more than half the U.S. population was born after 1982. You measure your current state against how things were maybe a couple years ago.

In September, a poll by Harris for my old employer USA Today found that: “Two-thirds of Americans believe younger people face hardships today that earlier generations didn’t, and 65% of Gen Zers and 74% of millennials say they believe they are starting further behind financially than earlier generations at their age.” The story went on: “They're telling us they can't buy into that American dream the way that their parents and grandparents thought about it ‒ because it's not attainable.”

Oy, sounds familiar.

And just in December, surveys showed that much of the U.S. population believes we’re in a recession even though the economy is actually, empirically, quite good. (See the statistics above.) Said one story: “The latest findings indicated nearly two-thirds of Americans, 66%, say the current economic environment – including factors such as elevated inflation, rising interest rates and changes in income or employment – has negatively impacted their finances this year.”

I’m guilty too. I’d like to climb back on my whiny horse and complain that 2023 sucked compared to, say, 2019 to 2021. It’s also easy to think that because things are like they are now, they are not likely to change, and that some crazy event – a war, a climate catastrophe, an alien invasion – will make things worse.

Yet I find my 1982 essay both embarrassing and heartening. As Mark Twain (may have!) said, “History does not repeat itself, but it rhymes.” My grandfather would tell me about getting by in the Great Depression on a can of beans and bathtub gin. To him, whatever was going on in the 1980s seemed near miraculous.

When I graduated college in 1982, as mortgage rates were 16% and unemployment was 10%, I had eight channels of TV I could watch, talked to friends on a rotary-dial phone attached to the kitchen wall, listened to music on cassette tapes, and had to walk into a store to buy anything.

Compared to that, what’s going on in 2023 is near miraculous. And if history rhymes, it will only get better. It would be a wonderful outcome if, some years down the road, all of you who are depressed about the economy today can look back on your outlook and feel as sheepish as I do now.

Unlike USA Today, The New York Times has digitized much of its content from the past. So this time, you can actually go to a link and read my old essay: https://www.nytimes.com/1982/05/22/opinion/82-gown-isnt-going-to-town.html?searchResultPosition=2

But here’s the image anyway…

December 3, 2023

A Christmas Tree Story

A lot of young journalists first make their mark by breaking an important story. You know, like Woodward and Bernstein with Watergate.

For me, that moment came when I wrote about the business of Christmas trees…as told in first-person by an actual Christmas tree.

I’d like to see Woodward and Bernstein try to get a story out of a tree.

In the fall of 1986, I had been at USA Today for about 18 months. I was one of the youngest reporters in the newsroom -- no doubt pretty cocksure, and very determined to write with creativity and flair, which didn’t always go well because newspaper editors in those days didn’t have a lot of affinity for creativity and flair. They just wanted the facts.

I also had a thing about being handed dumb, unoriginal story assignments. And that’s what I got when an editor tromped over to my desk, perched on a corner, and told me to write a story about the business of Christmas trees.

Probably every publication on earth had at some point published a straightforward story about the business of Christmas trees. It seemed to me like a holiday story idea that editors would come up with when they couldn’t think of anything better. But I couldn’t get out of it – I didn’t have enough mojo in the newsroom to argue against an assignment. So I tried to think of how I could do the piece in a way that might be a little different.

I suggested that I follow a single Christmas tree from the time it was cut down on the farm to after it was set up in someone’s home, and describe the businesses involved. The pitch got the green light. At that point I figured I’d write it in the third person, like a typical newspaper feature.

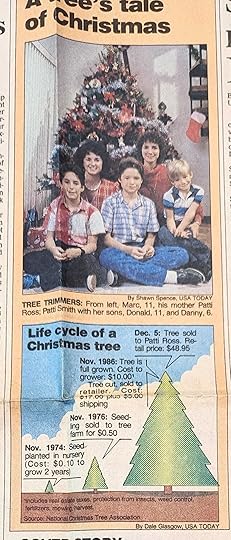

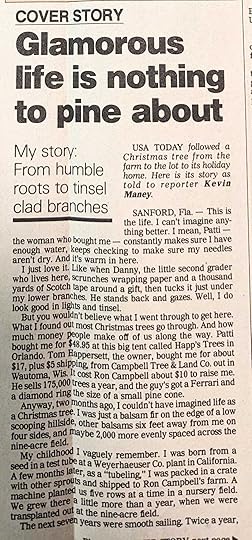

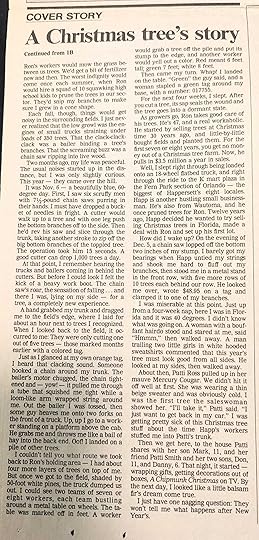

The story required two trips. I can’t recall how I found a Christmas tree farmer willing to participate in the story, but eventually I found Ron Campbell of Campbell Tree & Land Company in Wautoma, Wisc. He had a huge operation, selling 175,000 trees a year. As I pointed out in the story, he owned a Ferrari and wore a diamond ring “the size of a pinecone.” Clearly trees were a better business than I had expected.

(An unfortunate side note: While writing this piece, I googled Campbell Tree & Land, hoping to find a web site I could link to. I couldn’t find much about the company. Then I searched Newspapers.com – a massive collection of digitized newspapers from all over the country. There, I found a 1988 story in The Steven’s Point Journal, of Steven’s Point, Wisc., that said that two years after my story, Ron Campbell was flying his single-engine plane and was killed when he crashed near the Wautoma airport.)

I traveled to Wautoma and Ron, who was a delight, showed me the inner workings of the tree industry. I learned, for instance, about how he bought “tubeling” trees from a Wayerhauser operation in California that starts the trees from seeds. Campbell would then plant the tubelings in a nursery field, and a couple years later transfer the young trees to a massive hillside field where they’d grow for another seven years.

On a pleasant 60-degree day, he took me to the hillside, and we found a nice-looking tree that would be my target. I watched as it got cut down, sorted, tagged and loaded on a truck bound for a parking-lot Christmas tree stand in Sanford, Florida. The tag allowed me to know exactly where it was going.

Several weeks later, I flew to Sanford and found the tree stand, where I must have seemed like some kind of weird lurker hanging out by that tree and taking notes about the people who came by to check it out.

It was cold for Florida – 40 degrees. A few families looked over my tree and passed. Then a woman named Patti Ross pulled up in a Mercury Cougar. Shivering, she was ready to buy the first decent tree she saw. The sales guy, trying to help me out, guided her to my tree. That’s when I had to ask her if I could follow her home and watch as she and her kids set it up. Now, how weird was that? And how weird that she agreed!

Once Patti’s household decorated the tree, my research was done. Back in the newsroom, I gathered my notes and sat there trying to figure out how to write the damn story, and came up with a crazy idea: I’d write it from the tree’s point of view, in first-person.

And yes, at a newspaper in the 1980s, that was a crazy idea. Newspapers were serious. Maybe the reporters writing about fashion or movies could have a little fun, but writing about politics or business or crime – serious! I proposed the first-person tree idea and got shot down. I asked for a chance to write it that way on spec, and if it wasn’t acceptable, I’d rewrite it more, well, seriously. I got the OK.

I started the story with the tree luxuriating in Patti’s home, feeling fancy with all the decorations and attention. In the third paragraph, I wrote: “But you wouldn’t believe what I went through to get here. What I found out most Christmas trees go through. And how much money people make off of us along the way.”

Two paragraphs later, the tree starts its story: “I was just a balsam fir on a low scooping hillside…”

When I finished and turned in that version of the story, the paper’s top editors launched into a tense debate. The “we’re respectable journalists and we don’t do this kind of thing” faction wanted to kill it. But, apparently, there was another faction that really liked it and thought it was worth taking a chance. I’m eternally thankful that the story’s defenders won out. The story was published on December 18, 1986.

The first reactions I got were within the newsroom. Some reporters were on the “we don’t do this” side and were not happy. But a greater number were super positive. The story taught people a lot about the tree business, and was just fun. And by breaking the rules and succeeding, I got noticed. It was a significant leap for my reputation.

Then it got even more satisfying. This was long before email, so it took a while to get the public’s reaction. But before long I started getting calls and letters from people who loved the story. Next came the packages of drawings kids made in school after their teachers read them the story. Some of the teachers said they were going to make it part of their lessons every year.

In the years since, a couple of times I considered the idea of working with an illustrator to turn the story into a children’s book. Never followed through and made it happen. But when I had kids, I read it to them. I’ve pulled it out and sent it or read it to others many times over the years. To this day, it is one of my favorite moments in my journalism career.

Below are images of the story as it appeared in USA Today. It’s not available online.