Kevin Maney's Blog, page 3

August 13, 2024

I Miss Andy Grove

I’ve been thinking about Andy Grove lately – and, if he were still around, how disappointed he’d be with the company and country he loved so much.

I also miss him.

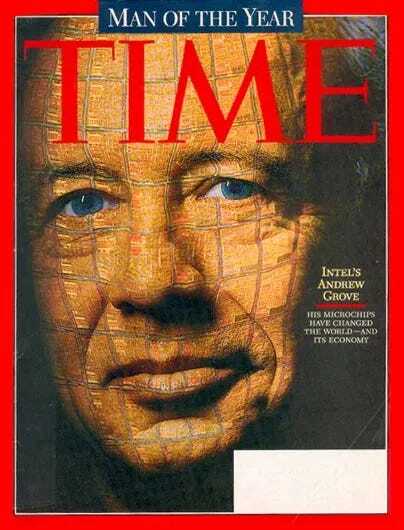

Not that long ago, Intel was one of the most important U.S. companies – and in 1999 the most valuable company on earth, the NVIDIA of its day. Intel was, quite literally, the engine underneath the early Silicon Valley-led tech ecosystem. Grove was on Intel’s co-founding team in 1968, became president in 1979, CEO in 1987, and finally retired in 2005. He published the influential business book Only the Paranoid Survive in 1996 and the next year was Time’s Man of the Year.

He was irascible, short-tempered, blunt, funny, deeply thoughtful and had a heart as big as a chip factory. I interviewed him a number of times – maybe more than any of the tech superstars of the day. He’d regularly read my columns and send one-sentence email commentaries that ranged from “This is interesting” to “This is stupid.” (Those were two actual emails.)

Intel is stumbling now. Its current CEO, Patrick Gelsinger, recently announced it is cutting 15,000 jobs – 15% of Intel’s workforce – as it restructures around a new manufacturing strategy and a push to quickly build new generations of chips to try to compete with NVIDIA and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. The U.S., thanks to Intel, once dominated global chip manufacturing, but that momentum has shifted to Taiwan – a problem for U.S. national security.

At the same time, the U.S. is struggling to uphold ideals that Grove cherished, particularly the belief that we are a nation that is stronger and better because of immigrants and the opportunity they find here.

He and I talked about that quite a bit. Grove was born in Budapest, and his family was Jewish. When he was eight, the Nazis occupied Hungary and sent 500,000 Jews to concentration camps, including Grove’s father. His father survived and unexpectedly returned to the family after the war, emaciated and unrecognizable to Grove.

In 1956, Grove was at university in Budapest when protests broke out against Hungary’s Soviet puppet government, and Grove joined in. A couple days later, the USSR shelled the city and Soviet troops stormed in to put down the uprising. One Soviet soldier busted into the Grove house while Andy was there, took Grove’s mother into another room, and raped her. Grove decided to get out of the country, and made a harrowing escape into Austria, then made his way to New York City. He arrived not knowing English and with no money.

Grove wrote about all this in his 2001 book Swimming Across, and I interviewed him about the book, just two months after 9/11.

But Grove, having landed in America, was smart and determined. He got an engineering degree from City College of New York (CCNY), which is cheap or free and has long been devoted to helping raise up those who come from less. He moved to California and in 1963 got his Ph.D. in chemical engineering from Berkeley. Five years later, Grove helped start Intel with Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore.

Immigration and CCNY were topics when I last saw him, in 2006.

He’d retired a year before, and I’d sent him a note asking what he’d been up to with all his free time. He invited me to come by the office he’d set up for his newly-formed Grove Foundation, in Los Altos, Calif. I wrote a story about it for USA Today. It starts out this way:

Andy Grove flips open a large pad on an easel to show me 11 handwritten note cards, which he taped in a formation. It's as charming and homegrown as a third-grade project. And it's meant to explain the home stretch of Grove's life.

So we're meeting at the foundation, which employs five people in an office so unremarkable it could be in the back of a small-town car dealership. Grove is wearing a light blue golf shirt and olive khakis, the BlackBerry on his belt buzzing constantly. His mood is up, his attitude at times mischievous, and he gives off the kind of lightness that comes from shedding boulders of responsibility and a schedule as tightly packed as transistors on a Pentium.

"I've given a great deal of thought to your question," Grove says, turning to the cards on the pad. I had asked to come by and talk about his retirement. That prompted Grove, for the first time, to think about all the things he's been doing in the past year and find a theme. On each card he wrote an area of interest or activity — "immigration," "City College of New York" — and moved them around with the help of his wife, Eva, until the cards' relationships made sense.

"What the foundation is really about," Grove says, "is to strengthen, regain and protect the America I came to."

At the time, there was an anti-immigration bill being debated in Congress. Grove lobbied against it and wrote opinion pieces that denounced it. He said if it wasn’t for CCNY, he’s not sure how he would’ve gotten a college education. To make sure new immigrants have that same chance, Grove gave the college $26 million.

He had another beef, which he’d only find worse today. As I wrote:

In general, he wants to do what he can to prevent religion from playing a role in scientific and medical research — as it did, Grove believes, in the U.S. government's decision to limit embryonic stem-cell research. "Respect for what science means is eroding," he says. "When people have strong beliefs, they confuse assertions with facts. Science is a respect for observation and facts in the face of beliefs."

See what I mean? He’d be horrified if he was still around, and no doubt pulling whatever levers he could to push back.

He’d be equally disgusted by Victor Orban’s autocratic rule in Hungary, especially Orban’s relationship with Russia’s Vladimir Putin. Grove had never returned to the country of his birth. “I didn’t like my life in Hungary,” he told me. “It would be like picking at scabs.”

About a year after our meeting, I left USA Today to join a Conde Nast magazine. For my last column, after writing it for about 15 years, I emailed a bunch of tech leaders I’d engaged with and asked if they wanted to get in any last shots. Grove wrote back in about two minutes. It was classic Andy:

“You almost got me lynched when you quoted, for reasons incomprehensible to me to this day(!), my comment likening PR people to Oompah Loompas. The only reason I’m alive is you were kind enough to stick it in a blog, which nobody reads.”

I had to return volley. At the end of that column, I wrote: “And, finally, to Andy Grove: I quoted you saying that because it was really stinkin’ funny. And now it’s in a column, which, apparently, a lot of people did read.”

By that time, Grove was showing signs of Parkinson’s. He died in 2016. The Computer History Museum held a memorial tribute to him, and I was touched that his colleagues and family wanted me to be there. Of course, I attended.

As I said, I miss him.

—

The story about our last meeting is in the link above. My story about his book “Swimming Across” is below. It originally ran in USA Today and then went out on the wires. This is as it appeared in the Home News Tribune in New Jersey.

I miss Andy Grove

I’ve been thinking about Andy Grove lately – and, if he were still around, how disappointed he’d be with the company and country he loved so much.

I also miss him.

Not that long ago, Intel was one of the most important U.S. companies – and in 1999 the most valuable company on earth, the NVIDIA of its day. Intel was, quite literally, the engine underneath the early Silicon Valley-led tech ecosystem. Grove was on Intel’s co-founding team in 1968, became president in 1979, CEO in 1987, and finally retired in 2005. He published the influential business book Only the Paranoid Survive in 1996 and the next year was Time’s Man of the Year.

He was irascible, short-tempered, blunt, funny, deeply thoughtful and had a heart as big as a chip factory. I interviewed him a number of times – maybe more than any of the tech superstars of the day. He’d regularly read my columns and send one-sentence email commentaries that ranged from “This is interesting” to “This is stupid.” (Those were two actual emails.)

Intel is stumbling now. Its current CEO, Patrick Gelsinger, recently announced it is cutting 15,000 jobs – 15% of Intel’s workforce – as it restructures around a new manufacturing strategy and a push to quickly build new generations of chips to try to compete with NVIDIA and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. The U.S., thanks to Intel, once dominated global chip manufacturing, but that momentum has shifted to Taiwan – a problem for U.S. national security.

At the same time, the U.S. is struggling to uphold ideals that Grove cherished, particularly the belief that we are a nation that is stronger and better because of immigrants and the opportunity they find here.

He and I talked about that quite a bit. Grove was born in Budapest, and his family was Jewish. When he was eight, the Nazis occupied Hungary and sent 500,000 Jews to concentration camps, including Grove’s father. His father survived and unexpectedly returned to the family after the war, emaciated and unrecognizable to Grove.

In 1956, Grove was at university in Budapest when protests broke out against Hungary’s Soviet puppet government, and Grove joined in. A couple days later, the USSR shelled the city and Soviet troops stormed in to put down the uprising. One Soviet soldier busted into the Grove house while Andy was there, took Grove’s mother into another room, and raped her. Grove decided to get out of the country, and made a harrowing escape into Austria, then made his way to New York City. He arrived not knowing English and with no money.

Grove wrote about all this in his 2001 book Swimming Across, and I interviewed him about the book, just two months after 9/11.

But Grove, having landed in America, was smart and determined. He got an engineering degree from City College of New York (CCNY), which is cheap or free and has long been devoted to helping raise up those who come from less. He moved to California and in 1963 got his Ph.D. in chemical engineering from Berkeley. Five years later, Grove helped start Intel with Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore.

Immigration and CCNY were topics when I last saw him, in 2006.

He’d retired a year before, and I’d sent him a note asking what he’d been up to with all his free time. He invited me to come by the office he’d set up for his newly-formed Grove Foundation, in Los Altos, Calif. I wrote a story about it for USA Today. It starts out this way:

Andy Grove flips open a large pad on an easel to show me 11 handwritten note cards, which he taped in a formation. It's as charming and homegrown as a third-grade project. And it's meant to explain the home stretch of Grove's life.

So we're meeting at the foundation, which employs five people in an office so unremarkable it could be in the back of a small-town car dealership. Grove is wearing a light blue golf shirt and olive khakis, the BlackBerry on his belt buzzing constantly. His mood is up, his attitude at times mischievous, and he gives off the kind of lightness that comes from shedding boulders of responsibility and a schedule as tightly packed as transistors on a Pentium.

"I've given a great deal of thought to your question," Grove says, turning to the cards on the pad. I had asked to come by and talk about his retirement. That prompted Grove, for the first time, to think about all the things he's been doing in the past year and find a theme. On each card he wrote an area of interest or activity — "immigration," "City College of New York" — and moved them around with the help of his wife, Eva, until the cards' relationships made sense.

"What the foundation is really about," Grove says, "is to strengthen, regain and protect the America I came to."

At the time, there was an anti-immigration bill being debated in Congress. Grove lobbied against it and wrote opinion pieces that denounced it. He said if it wasn’t for CCNY, he’s not sure how he would’ve gotten a college education. To make sure new immigrants have that same chance, Grove gave the college $26 million.

He had another beef, which he’d only find worse today. As I wrote:

In general, he wants to do what he can to prevent religion from playing a role in scientific and medical research — as it did, Grove believes, in the U.S. government's decision to limit embryonic stem-cell research. "Respect for what science means is eroding," he says. "When people have strong beliefs, they confuse assertions with facts. Science is a respect for observation and facts in the face of beliefs."

See what I mean? He’d be horrified if he was still around, and no doubt pulling whatever levers he could to push back.

He’d be equally disgusted by Victor Orban’s autocratic rule in Hungary, especially Orban’s relationship with Russia’s Vladimir Putin. Grove had never returned to the country of his birth. “I didn’t like my life in Hungary,” he told me. “It would be like picking at scabs.”

About a year after our meeting, I left USA Today to join a Conde Nast magazine. For my last column, after writing it for about 15 years, I emailed a bunch of tech leaders I’d engaged with and asked if they wanted to get in any last shots. Grove wrote back in about two minutes. It was classic Andy:

“You almost got me lynched when you quoted, for reasons incomprehensible to me to this day(!), my comment likening PR people to Oompah Loompas. The only reason I’m alive is you were kind enough to stick it in a blog, which nobody reads.”

I had to return volley. At the end of that column, I wrote: “And, finally, to Andy Grove: I quoted you saying that because it was really stinkin’ funny. And now it’s in a column, which, apparently, a lot of people did read.”

By that time, Grove was showing signs of Parkinson’s. He died in 2016. The Computer History Museum held a memorial tribute to him, and I was touched that his colleagues and family wanted me to be there. Of course, I attended.

As I said, I miss him.

—

The story about our last meeting is in the link above. My story about his book “Swimming Across” is below. It originally ran in USA Today and then went out on the wires. This is as it appeared in the Home News Tribune in New Jersey.

August 7, 2024

The Little Known and Long Gone Company That Created the Future of the Olympics

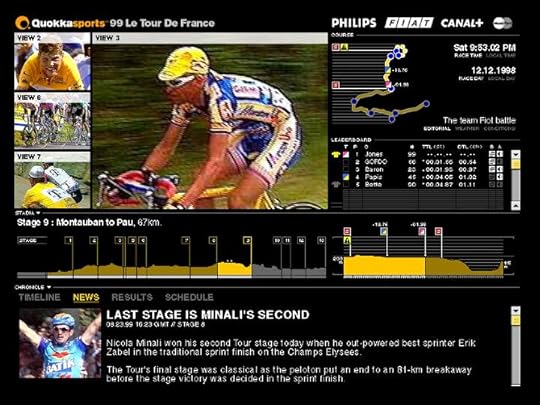

When you tune in to Olympics coverage, you probably take for granted all the cool graphics and detailed data that you see on the screen – how fast sprinters run, how a play developed in basketball, the angle of a discus throw.

Twenty-five years ago, none of that existed. But it was envisioned and predicted by a Silicon Valley company most people don’t remember, called Quokka Sports. The company didn’t survive the dot-com bust of the early 2000s, though its influence lives on.

My intersection with Quokka had an enormous impact on my life that I could not have predicted at the time. But more on that in a bit.

I first visited Quokka in 1998, when it was mostly focused on covering competitive sailing. That was its starting point, but even then the company had a vision for a future of digital immersive sports. Two years later, I revisited Quokka for a story after it signed a deal with NBC, which planned to use Quokka to enhance the network’s broadcasts of the 2000 Olympics.

As a journalist covering tech, I was always taken by companies that made me see a future that I hadn’t yet imagined – companies that gave me that classic “a-ha!” moment. That happened at Quokka. The consumer internet was new back then. The vast majority of people who were getting on it were doing so via painfully-slow dial-up modems. It took forever just to download a photo. Video was pretty much out of the question.

Quokka had an insight born in competitive sailing. One of the founders was Australian Al Ramadan, who majored in computer science at Monash University and was an intense athlete who got involved in sailing. In 1992, Al was asked by Australian sailing legend John Bertrand to be chief technologist for Bertrand’s upcoming run at the America’s Cup yacht race.

As Al told me then, Bertrand thought digital technology could give a sailing team an edge. So the team packed their boat with sensors that could send 50 variables to a computer, which in turn could track and analyze the incoming data.

“I’d be standing there during the race with all this information coming into my computer, and I realized all these people were gathered around me watching my screen instead of watching the boats,” Al said, as quoted in the story below.

He realized the onlookers were experiencing a different version of yacht racing than they’d ever seen – an intimate view of a sport that is otherwise far away out on the sea. What if that kind of experience could be available to the public – for sailing or any sport?

After the 1995 America’s Cup (won by New Zealand), Al went to Stanford to take a summer MBA course. The consumer internet was just getting going. Al and Bertrand made plans for a company that could use the internet to cover yacht racing in this new data-intensive way. Eric Schmidt – later of Google fame but then at Sun Microsystems – introduced those two to veteran technologist Dick Williams. Al, Bertrand and Williams founded Quokka in 1996.

By the late 1990s, every entity on earth wanted to get in on the dot-com boom, and that included NBC, which had the rights to the 2000 Summer Games. Yacht racing proved the concept, but NBC realized that what Quokka was doing could work for other sports. Quokka and NBC created NBCOlympics.com, the first internet site to cover the Olympics live. Quokka layered data into coverage of 35 sports, such as swimming and track.

So, what happened to Quokka?

It was a classic case, as we’d say in our work at Category Design Advisors, of getting too far ahead of the adjacent possible.

Technology and the public didn’t catch up to Quokka’s vision in time. In 2000, internet connections were still too slow for a good video experience, and much of the audience just wasn’t used to looking online to watch sports – a chicken and egg problem. The great dot-com crash that started in 2000 devastated Quokka’s stock price and soured investors on internet companies. The economy sank after 9/11 and advertising dried up.

In 2002, Quokka folded. As Al has said to me many times in recent years, if Quokka had been able to get through the storm of those years, today it might be a sports media giant. Instead, the company disappeared - but everything it envisioned has come true.

I liked Al from that first meeting and was fascinated by Quokka. For years after the company folded, any time I was researching a story about sports and technology, I emailed or called Al for his insights. After Quokka, Al had moved on to top positions at Macromedia and Adobe. Around 2011, he teamed up with Christopher Lochhead and Dave Peterson and launched a startup advisory firm called Play Bigger.

A couple years later, I got a call from Al, and he asked me to dinner with his partners. They had some interesting insights from working with startups, and thought that might lead to a book. They wanted to talk with me about it.

I liked what they were saying and the four of us started building on their ideas. We ended up co-authoring the book Play Bigger, which came out in 2016 and introduced the concept we called “category design.” The book has sold hundreds of thousands of copies worldwide, made category design part of the tech ecosystem, and led me to found Category Design Advisors with Mike Damphousse. (Al now runs the Play Bigger firm; Chris preaches category design with his Category Pirates; Dave is semi-retired and working on a professional pickleball career.)

In life, you never know what will lead to what.

Anyway, as a bonus, since Al and I still know each other well, I told him I was writing this and he offered his perspective on our early encounters when he was at Quokka. Here’s what Al sent:

Quokka was one of the hottest tech companies in the Valley in the mid-late 1990s. Investors included Accel Partners, Media Technology Ventures, Intel Capital, Liberty Media, NBC. Our “launch party” at Mission Cliffs climbing gym set a new high for launches in S.F. The Fire department came by and told half of the crowd to go home and to shut down the F1 car transmitting telemetry to the computers into the Climbing Gym where we displayed the data overlays on the climbing walls.

Two rock climbers scaled the longest pitches transmitting heart rates, XYZ positions and body temp. One jumped off the wall and her heart rate lowered. Most people in the crowd were captivated by the story the data was telling them. The data was, in many cases, more valuable than the live images… How could her heart rate go down when she is about to crash into the ground? (Her belay partner caught her a few feet from the gym floor).

Caryn Marooney from Outcast Communications had a line of reporters out the door. We were front page.

But very few of the reporters wanted to know anything other than our latest round of finance.

Somewhere in that craziness Caryn connected me with Kevin Maney from USA Today.

Kevin was different. He wanted to understand the experience we were delivering to sports fans and how it was different to conventional TV and print media. He wanted to know who we were serving. Sailors, Outdoor enthusiasts, extreme sports, etc – people who didn’t get TV coverage other than the occasional mention on Wide World of Sports.

Remember 1996? Mosaic Browsers. Then Netscape. Rich media was nascent. Video was impossible. People on dial up modems. Broadband penetration in the single digits…

Kevin asked a million questions. Probing the experience delivered and who we delivered it too.

I explained to Kevin that it was the mixing of data overlays, with live images/video coupled with interactivity delivering a new lens on the sporting event. If people were into the “story” they could hear it from the athlete - no reporter in between. If they were into the stats and who was gaining/losing, they could download our “Race Viewers” which gave you a million options to view the event.

If you were into participating you could join a “Virtual Race” not only against your friends but against the actual athletes themselves.

He got it. A fundamentally different way to experience a sporting event. He also got that some of these audiences were of great interest to non-traditional advertisers.

Kevin wrote the first article in 1998 centering on the Whitbread Round the World Race. That’s when everyone else got it too…

August 6, 2024

A Tourists Guide To a Big Tech Antitrust Trial

The news today is that Google was found by a federal judge to be an illegal monopoly. The case and the ruling have echoes back to the late 1990s, when Microsoft similarly got busted by the Justice Department.

I covered that Microsoft trial. And while I was there to watch for actual news, I thought readers would like to know what it was like on the scene. Below is the column I wrote for USA Today, which went out on the wires and appeared in many regional newspapers. The clip here is from The Olympian in Olympia, Wash., dated Nov. 30, 1998, as found on Newspapers.com.

For what it’s worth, after the column appeared, I got an email from Intel CEO Andy Grove. It just said, “This is funny.” He signed it, “Mad Puppy.” You’ll get the joke once you read the column.

July 13, 2024

Why Do Tech Superstars Invest In Huge Blunders?

Why do hyper-smart tech industry superstars keep investing in big, cool, futuristic ideas that seem destined from the start to fail?

In my three-plus decades of writing about technology, I’ve seen this over and over again, and I don’t get it. The list of past superstar-backed disasters includes General Magic, Teledesic and Segway. We’ve got a couple happening right now: Humane’s Ai Pin and Apple’s Vision Pro.

Marc Benioff, Sam Altman, Tim Cook, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, John Doerr, Motorola, Sony, Goldman Sachs…what were they thinking?

All they had to do was run the idea through a couple of tests:

1. Does it land in a good spot on the “adjacent possible” curve?

2. Does it solve a real problem that real people have now?

Whiff on either of those, and it’s best to walk away.

The most recent big whiff is the Humane Ai Pin. The New York Times did a terrific job of describing what it’s supposed to be, saving me some keystrokes: The two founders, who came from Apple, “set out to create a lapel pin that clips to clothing with a magnet. The device gives users access to an A.I.-powered virtual assistant that can send messages, search the web or take photos. It is complemented by a laser that projects text onto the palm of a user’s hand for tasks like skipping a song while playing music. It also has a camera, a speaker and cellular service.”

Salesforce CEO Benioff invested. So did OpenAI chief Sam Altman. Softbank and Tiger Global pitched in. The company raised more than $1 billion. They all apparently bought into the idea that AI pins would disrupt and replace smartphones.

But it fails the adjacent possible test. The adjacent possible is a concept borrowed from Steven Johnson’s book Where Good Ideas Come From. In our category design work, we use a modified version. In the graph below, the vertical axis is “what technology can do.” Horizontal is “what society can adopt.”

The green space, then, are things that exist, work, and have been accepted into our lives – smartphones, Bluetooth headsets, electric cars, TVs, microwave ovens and so on. The blue space is stuff that doesn’t really exist outside of a lab. The technology is untested, and we can’t get our heads around its use cases. You could put quantum computing firmly in the blue.

The border between those two, as Johnson explained, is the adjacent possible. Innovations catch on and change our lives when they land there. When a product or service nails the adjacent possible, it pushes the technology and creates something cool and new but it also works. And it pushes us all to adopt something cool and new that also seems relevant and understandable. That describes, for instance, the iPhone in 2007 and ChatGPT in 2022.

Introduce a product in the green “existing” space, and it’s probably a not-so-exciting incremental improvement on something we already use. Introduce a product in the blue “not ready for prime time” space, and it’s going to be too far ahead of its time. It likely won’t work well, won’t have an ecosystem to support it, and won’t seem worthwhile to anyone but tech gadget geeks.

A company that bets on a product too far into the blue almost always runs out of money before finding success. It gets the booby prize of being hailed as a visionary once that same thing succeeds a decade or two later – after the tech and the public have caught up.

From the first story I read about Humane’s Ai Pin, it seemed obvious it was too far into the blue – obvious it wouldn’t get traction in any near future. In fact, the company has struggled to make the technology work, as the Times story detailed. People in general are quite enamored with their smartphones, and so are years away from understanding why they’d want an AI pin to replace those phones.

As a result, Humane has no real market to sell into, and no healthy ecosystem of suppliers, developers and partners. The company is sputtering, top executives are leaving, and the press is eating it alive.

While we’re at it, we can try the other test: Does the pin solve a real problem that real people have now? Quick answer is: no. Perhaps the problem could be defined as having to carry around a 7-ounce powerful connected computer that fits in your pocket or purse. Are we desperate to ditch that for a wearable pin that can’t do a fraction as much?

Good tech businesses solve a real problem. Bad tech businesses get enamored with technology looking for a problem to solve.

Which brings us to Apple’s Vision Pro.

Yeah, it’s cool. But here’s the headline on a recent Forbes story: “Apple’s Vision Pro Is Amazing But Nobody Wants One.” The story points out: “This year Apple is now anticipating selling only around 450,000 Vision Pros, far short of their first-year target of 800,000. Compare that to the 73 million Apple iPads that sold in their first year.”

True, the Vision Pro may actually land near the adjacent possible. Apple has made the technology work, although it is bulky and expensive for what it does – kind of like early PCS or earliest cell phones. As for the horizontal axis – adoptability – we’re not there yet as a society. Most people don’t feel a pressing need to put on big goggles every day and disappear into a virtual world.

The “problem” test is a bigger issue for Apple. The Vision Pro is technology in search of a problem. Headline on a Financial Times story this month: “Apple seeks ‘killer app’ for its $3,500 Vision Pro headset.” That’s never a good sign. It means it’s a toy and little more.

Steve Jobs had always been good about showing us the problem his new products solved. The first Mac was a “computer for the rest of us” – because, as he showed us, PCs before that were too technical, corporate and uninviting. The iPhone combined a phone, computer, music device and internet device into one integrated gadget, solving the problem of owning and carrying all those separately. Yet when Cook unveiled the Vision Pro, his presentation was all about how cool it was instead of why it mattered.

Good products solve a real problem. Bad products get enamored with technology looking for a problem to solve.

I’ve seen these big whiffs happen – and wrote about them as a journalist – over and over. General Magic is a legendary example. Founded in 1990, it was essentially trying to build the entire consumer internet way ahead of the adjacent possible. It got a lot of the concepts about the web and mobile devices right, but too early to make the technology work or convince the public it was worthwhile. Like the Vision Pro, it was cool but didn’t solve anyone’s real problem – just a toy. Yet Motorola, Sony, AT&T, Goldman Sachs and Japan’s telecom giant NTT all invested or signed on as partners. Apple took a minority stake and then-CEO John Sculley joined the board.

The product and service never really worked. The actual internet bypassed it. By 1999 General Magic was collapsing and it shut down in 2004.

Teledesic, founded in 1994, was an attempt to build essentially what today is Elon Musk’s Starlink – but, again, too far ahead of the adjacent possible. At a time when most people were just discovering the internet on desktop PCs plugged into a modem, the public didn’t understand the problem of, “Why don’t I have mobile internet?” Teledesic was initially funded by Gates and cell phone billionaire Craig McCaw and it brought in Boeing, Motorola, Lockheed Martin and a Saudi Prince who alone put in $200 million. The company shut down in 2002 and never got operational.

Segway – same kind of story. Founded in 2001, Doerr, then one of the hottest VCs in Silicon Valley, and Bezos both invested. Jobs predicted it would revolutionize cities. You could argue that the original Segway met the adjacent possible test. It was a technological marvel that both worked and wowed the public. But it utterly failed the “what problem does it solve” test. Few people felt they needed one. Even now, the main problem it seems to solve is to help tourists who don’t want to walk see the sites.

Segway was bought by a Chinese company in 2015, which shut down production of the Segway “personal transporter” in 2020.

You may be thinking: If people like Bezos, Benioff and Gates make these blunders, what chance do the rest of us have? But the two tests in this article can help a lot. Next time you are introduced to a big, cool, futuristic product or business idea, try to place it on the adjacent possible chart – where does it land at the intersection of what technology can do and what people can adopt? Then ask: What problem does it really solve, and does that problem matter?

Of course, there will be some exceptions to the rule. But most of the time, if you’re looking at something that doesn’t meet those two tests…you might want to walk away.

June 27, 2024

The Odd '80s Restaurant Magnates and Me

Looking back at my clips from USA Today, apparently in the late 1980s I specialized in writing about odd chain restaurant magnates.

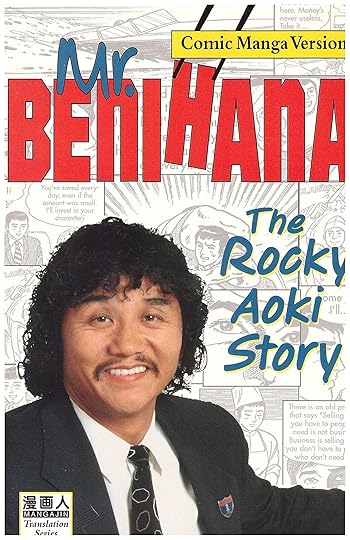

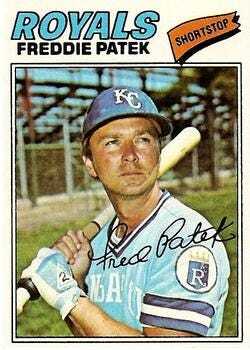

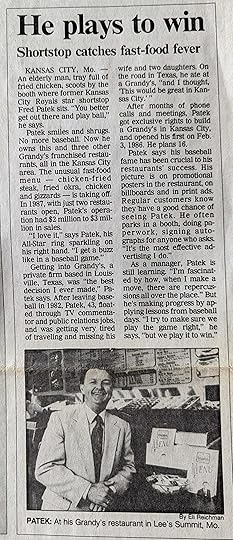

In the span of a few years, I met and interviewed Alvin Copeland, who started fried chicken chain Popeyes; Rocky Aoki, creator of Benihana; and Freddie Patek, the one-time star shortstop for the Kansas City Royals who owned a bunch of restaurants called Grandy’s Country Cookin’. Until I looked it up, I had no idea Grandy’s still existed, but it operates 23 restaurants across six states.

These stories were in addition to my profile of Tom Carvel, which I wrote about previously.

Copeland and Aoki, who both died in 2008, were certifiably weird. Patek was a lovely guy when I met him. He’s alive and now 79.

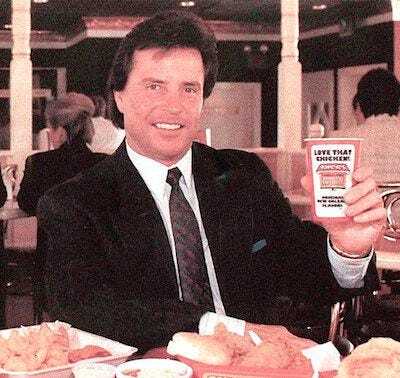

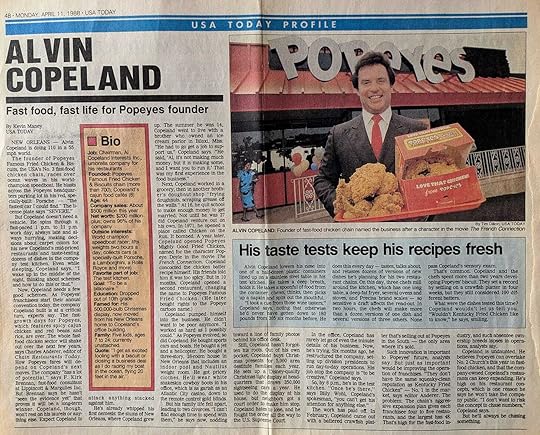

In the spring of 1988, I traveled to New Orleans to interview Copeland at Popeyes headquarters. Popeyes was having a moment, growing like mad (700 stores at the time, now 3,700-plus!), and scaring Kentucky Fried Chicken (which hadn’t yet changed its name to KFC so it could ditch the “fried” label). I remember sitting across from Copeland as he responded to my questions from behind his desk and thinking it was like interviewing a tornado – his words came at me fast and full of bluster.

Copeland then was 44. He dressed in expensive suits, had a perfect coif out of the Trump School of Eighties Hair, and owned a red Porsche with a license plate that said, SEVERE. Should tell you something. He also owned a Lamborghini and raced speedboats. I followed him around the Popeyes test kitchen at one point as he chewed prototype items and spit them out. “I learned something from those wine tasters,” he told me, noting that it was the only way he got down to 180 pounds from 205 in the previous six months.

Copeland was a good story. He grew up poor in New Orleans and never finished high school – which is why, as it was easy to see, he tried so hard to look rich and smart by the time I met him. As a teen, he worked at a brother’s donut shop, where he learned about the food business. In his twenties, he started one chicken place that flopped, then a year later opened the first Popeyes, basing it on the Louisiana staples he grew up with – chicken, rice and red beans, and biscuits. He named the restaurant Popeyes not after the cartoon character, but after a character in the movie “The French Connection.” A year after that, Copeland opened a second one and then kept going.

Copeland, though, ran into rough times soon after my visit. Popeyes in 1989 took on a pile of debt to buy rival Church’s, and then in 1990 defaulted on the loans and filed for bankruptcy. Creditors took over and booted Copeland. Now the company is owned by Restaurant Brands International. Soon after all of that, Copeland wound up in a public feud with horror novelist Anne Rice because she placed a full-page ad calling a new restaurant Copeland opened “nothing short of an abomination.” In 2007, Copeland was diagnosed with a rare cancer, and he died in 2008 at 64. Popeyes lives on and in 2019 launched what became known as The Chicken Sandwich Wars, which gave Popeyes the more publicity than it had gotten in decades.

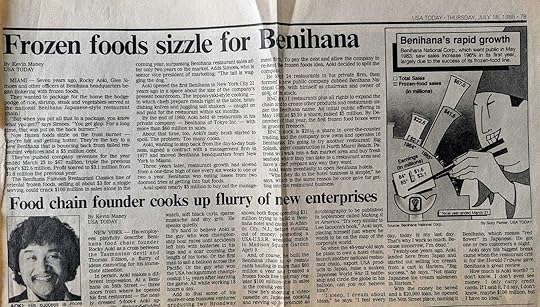

Aoki was a 5-foot-4 Japanese version of Copeland. Same crazy energy. “I sleep, I dream about ideas,” he told me. “I feel every day is my last day. That’s why I work so much. Because tomorrow, I’m dead.” He had the same tendency toward flash, too: tailored suits and, when I met him, a diamond-studded watch. He owned fast cars and like Copeland raced speedboats.

Aoki landed in New York from Japan in 1960 and sold ice cream from a cart in Harlem to get by. Three years later, he opened a four-table restaurant on 56th Street in New York, naming it Benihana after a flower that grew in Japan. By the time I talked to him, he had 48 Benihana restaurants and had gone public in 1983. He’d also won championship boat races, had horrific speedboat accidents, crossed the Pacific in a hot-air balloon and won the USA backgammon championship.

And, like Copeland, Aoki got into trouble. In 1999 he pleaded guilty to insider trading charges and was nearly deported. In the 2000s he ended up suing four of his children for allegedly trying to take control of the companies he founded. His death in 2008 was supposedly from complications from a hellacious speedboat crash almost three decades earlier. Now Benihana is owned by One Group Hospitality and operates 68 restaurants.

Finally, there is Fred Patek. I grew up watching him play for the Kansas City Royals in the 1970s. I was a fan of that superstar team, which included George Brett and Amos Otis. Patek was one of the stars, and specialized in stealing bases. He was, like Aoki, small – at 5-foot-5, the shortest player in baseball at the time. In his rookie season in 1968, Patek reportedly had an exchange with a newspaperman who asked Patek: “How does it feel to be the smallest player in the majors?” Patek replied: “A heck of a lot better than being the tallest player in the minors.”

I met Patek in 1988, seven years after he’d retired. We sat and talked at a booth in a Grandy’s in Kansas City, and he was gracious as patrons came up to him to chat, ask for autographs, or to tell him he should get back out there because the Royals needed him. The only thing flashy about him was his All-Star ring.

Patek told me that after he retired, he tried being a baseball commentator and doing TV commercials, but didn’t like the constant travel. He had wandered into a Grandy’s in Texas and liked the Southern cooking concept – the menu included chicken-fried steak (which I tried and it is delicious but it’s just breaded and fried steak, a classic “heart attack on a plate”), fried okra and chicken gizzards (I did NOT try the gizzards). Patek bought rights to open Grandy’s in Kansas City and owned four when I interviewed him. “I love it,” Patek said about running the restaurants. “I get a buzz like in a baseball game.”

Actually, I doubt that was true. Managing a restaurant chain or playing shortstop for an MLB team…which would give you a bigger adrenaline rush?

Anyway, Patek seems to have avoided controversy. Grandy’s as a whole went through a series of ups and downs and acquisitions and has been owned by restaurant holding company Captain D’s since 2011. Patek moved back to Oklahoma City, where he was born. He remains the second shortest player in MLB history, behind Wee Willie Keeler, who retired in 1910.

—

These are the stories as they appeared in USA Today in the late-1980s. They are not available online.

June 7, 2024

The Doug Burgum I Kind Of Knew...and Liked

I can’t say I ever knew Doug Burgum well, though until recently I still got his family Christmas card. But it’s hard for me to imagine the Doug Burgum I did know desiring to be Donald Trump’s running mate.

Burgum is, according to news reports, on Trump’s “short list” for VP. Most of the public knows Burgum as the governor of North Dakota who entered the Republican primary race for president, seemed low-key and boring during the debates while looking a little like Eugene Levy, and then quickly dropped out.

My encounters with Burgum were all in the late-1990s and early-2000s. Burgum was a fascinating anomaly in the dot-com era: He’d built a billion-dollar accounting software company called Great Plains in Fargo, N.D., a city that most techies only knew as the setting for a Coen brothers movie. He had long hippie-like hair, a big smile, and milled around with Silicon Valley preppies wearing flannel shirts and jeans as if he’d just dropped in after inspecting a grain elevator. He struck me as kind, principled and rooted in the type of warm rural populism you might get in a John Mellencamp song.

I talked to him at tech conferences like PC Forum and Agenda. He was friends with investor Heidi Roizen and I’d run into him at the enormous parties she’d host in Silicon Valley. I liked getting his input when writing columns and stories because he’d get philosophical and draw on far-flung historical analogies such as the building of the transcendental railroad or the travels of Marco Polo.

I have a printout of an email exchange we had in 1998, when I was working on a story about “internet time.” In that late-‘90s dot-com frenzy, the buzz was that the internet “changed everything,” including the nature of time – that everything was happening exponentially faster than it used to. Doug wrote:

The big change with the internet was not the pace of change, but the change of pace (and scale) in which new companies could raise capital and attempt to displace competitors (or create new categories).

At the “receiving end” of our industry, i.e. customers, there are limits for their desire and motivation to accept (pay for?) even more change in their lives. I say pushed, since most change is “pushed” by companies/start-ups vs. being “pulled” (demanded) by consumers. The real pace of change of the masses (vs. “serial” early adopters) is still limited by our nature as humans.

I love that! And, damn! It totally applies today.

Burgum was born in Arthur, N.D., and while in college at North Dakota State started a chimney sweeping business. That apparently helped him get into Stanford business school in 1978, where he not only got exposed to that area’s growing technology industry, but also became buddies with classmate Steve Ballmer, who would eventually end up as Microsoft’s CEO. Burgum went back to North Dakota, and mortgaged family farmland so he could invest in Great Plains, then a tiny software company. Before long, he and his family bought the whole business, and Burgum grew the company to about $300 million in annual sales and, in 1997, an IPO.

In 2001, Microsoft bought Great Plains for $1.1 billion – a year after Ballmer became CEO. (Coincidence? Hmm.) Burgum joined Microsoft and ran its Business Solutions Group. He left in 2007, and the person who was promoted to Burgum’s job was Satya Nadella, who is now Microsoft’s CEO.

Back in Fargo, Burgum invested in tech companies and real estate in the northern Midwest. With no political experience (though a lot of wealth), he ran for governor of North Dakota in 2016 and won. He won again in 2020. From what I know of his time as governor, he never seemed super-conservative, much less MAGA-like. (Well, he did cut his hair.) He actually acknowledges climate change and pushed for carbon-neutral policies for the state. He’s for aid to Ukraine to stop Russia. He also actually said the words: "I believe that Joe Biden won the election." How he wound up in Trump world…well, who knows how anything happens in Trump world.

Anyway, I once sort-of knew a Doug Burgum who I would never have thought would be the Doug Burgum who is a Trump veep short-lister. Or, maybe Trump is interested in Burgum because he is, in fact, that same down-home, soft-spoken, thoughtful guy who knows a lot about history. The stark contrast might help.

I quoted Burgum in quite a few stories and columns for USA Today, but they are not available online. I have no idea why I saved printouts of some of his emails back then.

May 29, 2024

The Economy of the Indy 500

The Indianapolis 500 happened over Memorial Day Weekend, as it always does. I didn’t watch it on TV. Apparently, in relative terms, not many people did. Yet the prize money has rocketed through the roof.

This is quite a change from 1988, when I spent time in the racers’ garages at the Indy track and wrote a feature about the business of racing in the 500.

At the time, as my story reported, about 24 million people watched the Indy 500. This year, viewership during the four-hour race peaked at 6.5 million. In 1988, the winner, Rick Mears, got about $810,000 -- $2.2 million when adjusted for inflation. This year’s winner, Josef Newgarden, raked in $4.3 million. So prize money has doubled while the TV audience has shrunk to about one-fourth the size.

But the surprising thing I found out back then about the Indy 500 is that the prize money is barely the point when it comes to the economics of racing. Really, it’s all about being a 200 MPH billboard.

I did most of my reporting on practice day, a few days before the actual race. I had a pass to wander around the garages where the drivers and their crews fine-tune their cars while other cars whizzed by on the track making an enormous noise. I knew little about racing and could barely figure out how to check the oil in my car. Yet it was super cool to see what was going on behind the scenes – which was kind of like what was depicted in the movie Ford vs. Ferrari.

What I hadn’t expected was such a clear socio-economic divide in the pits – something viewers at home don’t see.

I walked over to the area where racing legend Mario Andretti’s team was set up. They had three garages, 25 mechanics in matching outfits, two Lola cars and 10 backup engines.

Not far away was a driver named Phil Krueger. He had one garage, one car, one mechanic, one spare engine and no matching outfits. His team was owned by R. Kent Baker, then a young guy who owned an Indianapolis marketing company called CNC System Sales (which still exists and Baker still runs).

As I talked to Krueger and another shoestring-operations driver named Tony Bettenhausen, I learned that the big gulf between these camps was sponsorships. The Indy 500 has the same kind of economic dynamics that you see everywhere today. Winning cars get more time on camera, which equals more exposure for the brands plastered on the cars – brands like Valvoline, Pennzoil, Pizza Hut and Verizon. Winning drivers also get personal time on camera, where the brand logos on their outfits get seen. So, the brand sponsorship money rolls in for the winners, which gives the winners more money to spend on better cars, engines and mechanics…so they win more and bring in yet more sponsorship dollars. The rich get richer.

And it became obvious why the poor usually stayed poorer. The side of Krueger’s car had a CNC Systems decal because the team couldn’t land any paying sponsor for that spot. Krueger had one other logo on the car — for a trucking company called Taylor Distributing, which, I wrote, “pitched in a few bucks to help.” Other than a tiny Valvoline sticker, that was it.

Bettenhausen’s logos included a nine-store grocery chain and an Oldsmobile dealership. To drum up support and help out his sponsors, Bettenhausen was doing a rush-hour radio show from his garage with a local DJ.

In the decades since, it seems like not much has changed about sponsorships and Indy. Newgarden’s winning car sported a Shell oil company logo and the whole car was decked out in Shell colors – as was his outfit and those of his whole pit crew. The team was a walking Shell ad and Newgarden probably got a fortune for it – in addition to his $4.3 million prize.

In that 1988 race, Krueger, with almost no sponsorship money and a tiny operation, finished an amazing 8th place out of 33 cars in the field. He got $131,053 in prize money for it, and then never raced in the 500 again. He tried to qualify the following two years and failed. Can’t find anything online about what Krueger is doing now.

Mario Andretti, by the way, finished 20th that year. Engine trouble forced him out before the race was over. So, I guess it’s gratifying to know that money doesn’t guarantee a good outcome.

Bettenhausen…well, he finished last. The web says Bettenhausen died in 2014. A friend of his wrote an obit that noted: “He went to sleep in the basement on Sunday afternoon and never woke up when his wife of 50 years, Wavelyn, called him for dinner.”

—

This is the story as it ran in USA Today in 1988. It’s not available online.

May 20, 2024

The Time I Hung Out With Tom Carvel, Talking Soft-Serve

I was watching Jerry Seinfeld’s silly and fun movie Unfrosted, and at one point his character introduces the legends of TV-age invention who he’s hired to help develop what would become Pop-Tarts. The team includes Chef Boyardee, Jack LaLanne, a Univac computer, and…Tom Carvel.

Who I spent a day with in 1986 at Carvel’s Yonkers, N.Y., headquarters.

I grew up in Binghamton, N.Y., with a Carvel store a half mile away and Carvel commercials constantly on TV. Seinfeld’s movie doesn’t even remotely try for historical accuracy, but one thing it gets so very wrong is Tom Carvel’s voice. The actor playing him is Adrian Martinez, and he only has a few lines, but he whiffs on Carvel’s distinctive, mumbly, chatty delivery. In the story I wrote for USA Today, I described Carvel’s sound as a cross between Brando’s Godfather and the Cowardly Lion in the Wizard of Oz.

Now, a guy who built a chain of middling ice cream shops (by today’s standards) and whose name in the 2020s is most widely associated with Fudgie the Whale and Cookie Puss ice cream cakes might not seem like an important historical figure. But he kinda is.

First of all, he’s the one who made soft-serve ice cream a thing – created and built the category, as we’d say in our consulting work.

Carvel, a Greek immigrant, had been an auto mechanic in New York, then worked on refrigeration units for the U.S. Army, which led to him driving an ice cream truck in Westchester County, N.Y. The story goes that in the early 1930s, his truck got a flat tire on a hot day. Instead of wasting the ice cream in the back, he pulled into a parking lot and started selling it as it became soft. His newfound customers loved it, and he had an epiphany that soft ice cream could be a good business.

Carvel probably didn’t invent the first soft-serve machine, but he invented and patented the first practical, lower-temperature machine that could be installed in a storefront. He opened his initial shop in Hartsdale, N.Y., in 1934. By the time I interviewed him, Carvel had 865 stores in 17 states and six countries, bringing in $300 million in annual sales. Tom Carvel still owned 90% of the company.

What I guess I didn’t expect when meeting Carvel was that he was so self-regarding and a name-dropper. I did the story because Carvel was then 80 and looking to sell his company. He’d already spurned an attractive offer from Twistee Treat because they didn’t play by his rules. “I might still do business with them, but in our own way, on our own time,” he told me. I added in my story: “That’s how it is around Tom Carvel: only two ways of doing things – his way and the wrong way.” This is the guy who put out commercials that looked like home movies and featured toddlers or cakes with names like Dumpy the Pumpkin. Who’d have guessed?

He also made some boastful claims I couldn’t corroborate. He said that Ray Kroc copied the structure of his stores for the first McDonald’s, which opened in 1940. In my story, I wrote: “From a lower drawer, he pulls out a picture of one of the first Carvel stores and another, dated years later, of an early McDonald’s franchise. Except for the golden arches, they’re nearly twins. Carvel claims it’s no accident.”

Tom Carvel was also one of the first CEOs to do his own TV ads. It started, he told me, in the 1950s, when he felt that radio announcers never got the tone right when reading the advertising copy he sent them. So one time, at a radio station live, he took the mic and ad-libbed an ad. From then on, he voiced every ad, usually un-rehearsed. Fast-forward to the 1980s, and Carvel claimed to me that he advised Chrysler CEO Lee Iacocca on how to do his car commercials.

Oh, and at the musty, industrial-looking Carvel headquarters, hallways were lined with photos of Tom Carvel posing alongside celebrities like Howard Cosell, Danny Thomas and Bert parks. “When I get down, I call Bob Hope and have a few laughs,” he said with a straight face.

About three years after our encounter, Tom Carvel sold the company to Investcorp for $80 million. Tom Carvel died about a year after that, in October 1990. In 2001, Roark Capital Group bought a controlling interest. Carvel’s website now lists 340 locations in the U.S. – less than half of its peak under its founder.

—

This is the original story I wrote for USA Today, appearing on July 21, 1986. It’s not available online.

May 7, 2024

When Burger Diplomacy Seemed Like a Breakthrough for World Peace

Early in my novel Red Bottom Line, the protagonist, Jeff, is hanging out at a bar in the Washington, DC, area with his hockey teammates after a game. Jeff at this point in the book is pretty self-centered and clueless about the world. As he and his friend Turk chat over a beer, a news report from Moscow appears on the television:

The report cuts to shots of Russians marveling at Moscow's Pizza Hut and dining at the famed Moscow McDonald's. The correspondent expands into an analysis of why U.S. fast-food companies are finding Moscow so attractive. While he talks, another shot catches a stout old woman wearing a scarf tied over her head as she eats a Big Mac one layer at a time, starting with the top of the bun, moving on to the pickle, the onions, lettuce, hamburger patty. Turk cracks up laughing.

"That's hilarious!"

"That's the first time those people are seeing fast food?" Jeff says.

"Yeah. Where have you been? This story's been all over every kind of news for two years. It's the biggest thing that's happened to Moscow since Stalin croaked."

I actually witnessed that woman eating her Big Mac from the top-down. In 1990, thanks to a chance meeting on a flight to Moscow, I got to be a special guest at an enormous geopolitical and cultural event: the opening of the first McDonald’s in Russia. I wrote a lengthy story for the magazine USA Weekend about the crazy details behind that McDonald’s.

It can be hard for people today to imagine, but in 1990, the vast majority of Russians had no experience with anything from the U.S. Levi jeans and Marlboro cigarettes were hallowed fantasy items there. Few Russians had ever seen CNN. But as the Soviet Union disintegrated, the nation slowly opened to the West. I started traveling to Moscow to write about it.

On one of my flights over, I got talking to my rather chatty seatmate, who turned out to be George Cohon, who ran McDonald’s Canada, one of the biggest McDonald’s franchisees in the world. At that point, he’d been negotiating with the Soviets for more than a decade to bring McDonald’s to Moscow, and he was just starting to develop the building that would house it on Pushkin Square. Cohon invited me to come by and hear his story. This is maybe two years before the actual opening.

So I went to the site and saw a huge older building that had been gutted, ready for construction of the restaurant inside. I remember Cohon saying his crew thought the building had been previously used by the KGB, and when they knocked down some walls, they found what they believed were human bones. I think he told me at the time to keep that off the record.

Some of the other details I learned from him then and until the 1990 opening still seem amazing. His team had to bring in Russet Burbank potatoes for french fries and teach Soviet farmers how to grow them. Homegrown Russian potatoes might’ve been staples for millions in that country, but apparently they were crap for making fries.

Cohon’s team also had to hire and train Muscovites to work in a setting unlike any they’d ever experienced. As I wrote in the story: “McDonald’s one-day help-wanted ad in the newspaper Moskovsky Komsomolets was a shocker for Muscovites. For starters, they had never seen a help-wanted ad – much less one that called for ‘individuals who are not afraid to work hard.’ Yet by the next morning, paper sacks bulging with applications piled up in McDonald’s offices in the nearby Minsk hotel.”

The McDonalds’ team made plans for how to train customers, too, by showing videos outside the restaurant of how to order and eat the food. “We had to explain what a milkshake is,” I quoted Cohon as telling me.

After seeing the construction site, I kept in touch with Cohon, and he promised to invite me to the opening on January 31, 1990. Thinking back on the scene that day, I’m struck by how much the Russians craved anything American – how fascinated they were by the U.S., and how it seemed possible our two nations might actually come together. The line outside the restaurant was blocks and blocks long. Cohon estimated that 38,000 people were there. Some waited hours in the winter cold. The scene inside looked like a McDonald’s but not like any McDonald’s I’d ever been in. It was at the time the world’s largest McDonald’s, and it was cavernous and of course utterly packed. Menus were in Cyrillic. And a lot of people were a little bewildered by the both the construction and taste of the burgers.

After the opening, McDonald’s exploded in Russia. In 1997, the company had 21 restaurants in Russia. By 2020, there were 800, employing 62,000 people. And then Vladimir Putin’s government decided to invade Ukraine. In May 2022, McDonald’s announced it was exiting Russia and sold its stores to Alexander Govor, an oligarch invested in mining, construction, oil refining and forestry. There is no indication he ever knew anything about restaurants. He renamed all the McDonald’s as Vkusno-i Tochka, which translates as "Tasty and that's it." (Which, now that I think about it, is kind of an appropriate description of McDonald’s food.)

George Cohon died in November 2023 in Toronto at 86 years old. He wrote a book about his Moscow experience, To Russia With Fries.

--

I wrote a few stories about the Moscow McDonald’s for USA Today and USA Weekend. Unfortunately none were digitized by either publication. One story, about the upcoming opening of the restaurant, was published through Gannett News Service in The Republic in Columbus, Indiana, on January 27, 1990 – thankfully preserved on Newspapers.com. The Republic didn’t run all of what I wrote, but here is the version that was in the paper that day.