Kevin Maney's Blog, page 2

March 12, 2025

The Long Road to Robot Butt Washers

I just installed my first smart toilet – 20 years after writing about the entrepreneur who helped bring those things to the U.S. market.

Two decades ago, smart toilets were a bizarre idea to Americans – another weird thing that the Japanese came up with, like chopstick fans. (You know, a tiny fan that attaches to your chopsticks to cool down your noodles as you eat them. You don’t have one?)

Today, smart toilets are a mainstream luxury item. You don’t need one…but I know you want one. Or if you’ve used one at a nice hotel or a friend’s house or the Korean Air Lines lounge in Seoul, you’ve probably ever since been daydreaming about one.

If you know anything about smart toilets, you probably know the brand Toto. Through a category design lens, Toto is both the creator of the smart toilet category and the winner of its dominant design. Toto was founded in Japan in 1917, at first under the name TOYO TOKI CO, Ltd. In the 1960s, it started working on a combination bidet and toilet seat for the hospital market, for patients whose limited mobility made it hard for them to clean themselves.

The company tried to sell it to consumers, but consumers didn’t like it, mostly because the water was always cold and the spray went, like, all over the place.

Then came the 1970s, an age of Japanese inventions such as the VHS machine, the Walkman and karaoke. (Yes, karaoke is a product of the seventies.) This is the era when Toto’s engineers got the idea of marrying electronics to their bidet toilet seat.

In Toto’s telling of the story, this may be my favorite part:

TOTO engineers worked tirelessly to find the ideal angle at which water should spray from the wand. Although this data was vital to the new bidet seat’s development, testing directly on an individual’s rear end was met with significant employee resistance. It was challenging to get staff members to cooperate, especially women.

I picture one of the more bizarre product testing labs ever. And, by the way, the ideal angle the Toto engineers came up with was 43 degrees.

Anyway, in 1980, Toto launched its first Washlet electronic bidet toilet seat in the Japanese market. It wasn’t great. Toto says a lot of consumers didn’t like it. But those Toto engineers and rear-end testers pressed on, and by the 1990s the company had a version of the smart toilets you see today. They caught on in Japan, and Toto started selling them in the U.S.

Still, Americans didn’t get it. Sales were slow.

Toto established a new category of smart toilet – yet for at least a decade, Toto was the only company in the category in the West, which was problematic. When a market category has just one player, the public often ignores the category. People don’t get why they need this new thing, and no other company is coming in and validating that this category might be worth competing for. As happens in most new categories, Toto was going to need competitors to give it legitimacy.

At a tech conference in 2005, James Hong told me about a smart toilet he just bought. If that seems out of bounds for a conversation at a tech conference, keep in mind that at the time James was best known for starting the controversial website Hot or Not, which rated people’s looks. (Some argue that it was a precursor to Instagram, Twitter and other social sites.)

James’ smart toilet was not from Toto. It was from Brondell, and James knew the guy who started it, Dave Samuel. So he introduced us.

Prior to this, I was completely unaware of smart toilets. But as a tech columnist, I couldn’t resist. I called Dave Samuel, and he told me one of the best “founder insight” stories ever. Here’s how I wrote about it in 2005:

“In 1990, after Dave Samuel graduated from high school, his father took him along on a business trip to Tokyo. One night, the two went to a business dinner at a restaurant. Samuel excused himself to go to the bathroom and found himself staring at a toilet seat studded with buttons and electronic controls.

“‘I’d never seen this,’ Samuel recalls. ‘It had Japanese characters, so I couldn’t read what the buttons meant, But, of course, I had to press the buttons to see what they’d do.’

“He pressed one that extended a wand inside the bowl. The wand then sprayed warm water upward to wash whatever areas a seated person might need to have washed.

“Except Samuel wasn’t seated. He was still standing, fully dressed, facing the toilet and gawking. The spray soaked the front of his pants. He launched into a frenzy of trying to dry himself before rejoining his father and a bunch of Japanese businessmen, ultimately slinking back to the table and throwing a napkin over his lap.”

Samuel never forgot the strange toilet. Nine years later, he sold a startup to AOL, and he thought it “was time to introduce this to America,” as he told me. After a few years of development, the company Samuel founded – Brondell, named after J.F. Brondel, who invented the flush toilet in 1738 – started selling its $500 Swash 600.

To tell Americans about the concept, Samuel made an infomercial starring his grandparents, who were soap opera stars from Days of Our Lives. Within a month after my column appeared, Mark Cuban pumped $1.3 million into Brondell. The category picked up a little momentum, but remained small in the U.S. even while catching fire in Asia.

Over the next decade, other companies entered the category – Kohler, Moen, a few Chinese companies. That helped American consumers feel like smart toilets were more than just a curiosity.

Then, in 2020, Covid came along, and if you remember, toilet paper disappeared from shelves.

Suddenly, having a toilet that ends the need for toilet paper seemed like a really good idea. That, combined with gathering category momentum, helped smart toilet sales surge. The global market was about $3 billion in 2020, almost all not in the U.S. In three years, it tripled, much of it driven by the U.S. Some reports say it will grow another 50% by 2029.

Most thriving categories require what economist Paul Geroski, who studied market categories, called a dominant design. Mainstream buyers don’t want to have to choose between a bunch of products that work in wildly different ways. We like a standard.

It’s interesting to look back and realize that Toto first established the dominant design for smart toilets, and won it over time. All smart toilets work pretty much like Toto’s.

And that’s a powerful position. The company that establishes the dominant design usually controls the biggest market share – and Toto has the category’s biggest share, at about 30%. The dominant design winner also usually gets pricing power. A high-end Toto toilet can cost two or three times more than a similar model from Brondell or most other makers.

We bought a mid-priced Moen. These days the category is mature enough that there are many good choices. Toto has evolved into a global high-end bathroom company – toilets, fancy bathtubs, faucets. Brondell similarly expanded its product line into things like water filters and shower fixtures. Dave Samuel is now general partner at venture capital firm Freestyle. James Hong now describes himself as a family man and investor.

Lots of change in 20 years.

–

This is my column as it appeared in USA Today on November 23, 2005. I accessed it through Newspapers.com. It’s not otherwise available online.

February 22, 2025

OK Go, YouTube and the Adjacent Possible

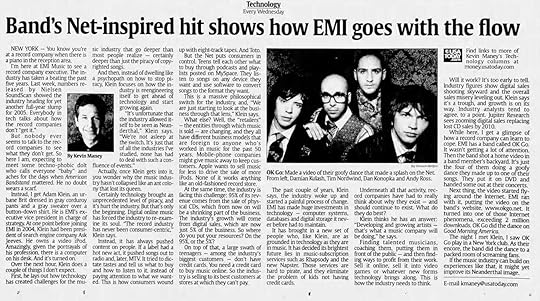

In the fall of 2006, just 18 months after YouTube was founded, I met two founders of the band OK Go – Damian Kulash and Tim Nordwind – at the Soho Club in New York to interview them about their breakthrough online videos.

OK Go was the first YouTube-made rock band, more popular for its choreographed performance-art stunt videos than its actual songs. What I didn’t understand then was that OK Go’s early success was a terrific example of a tech-industry concept I’ve written and lectured about called the adjacent possible.

And, bizarrely, OK Go is going on tour – a tour they are calling “The Adjacent Possible Tour.”

Now, I haven’t seen or talked to the OK Go guys in at least 15 years, and I’m 100% certain they have better things to do than follow what I’m writing or talking about. So the overlap about the adjacent possible must be a total coincidence. But still – I wanted to find out.

Let’s go back a bit. I first learned about OK Go in 2005, when I visited EMI Music in New York to do interviews about how the big record labels were dealing with the surging internet. Record companies had battled Napster and were trying to figure out Apple’s iPod. The industry was still getting 95% of its revenue from selling CDs – a fast-dying business model.

I wrote: “Everybody in tech talks about how the record companies don’t ‘get it.’ But nobody ever seems to talk to the record companies to see what they don’t get. So here I am, expecting to meet some techno-phobic dolt who calls everyone ‘baby’ and aches for the days when American Bandstand mattered.”

Instead, I found thoughtful executives who realized that the record companies’ operating model had to shift 180 degrees. Record companies had always pushed content to the public. They were the ones who decided what people would listen to. The internet was creating a different dynamic. Once people could easily access any music, the public would tell the record companies what they wanted. The role of record companies would be to respond to pull.

To give me an example of this shift, EMI’s executive VP at the time, Adam Klein, told me about OK Go, a band I knew nothing about. After making their first album, the four band members shot a home video of them doing a goofy dance routine to one of their songs. Before that, EMI didn’t push the band and the album’s sales were slow. But that video instantly flew around the internet, got millions of views, and OK Go found themselves invited to be on Good Morning America. EMI started paying attention.

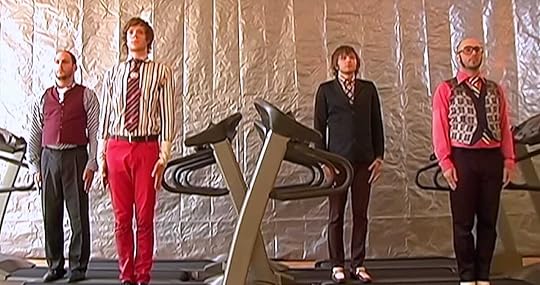

To their credit, OK Go and EMI then got intentional. They called in Kulash’s sister, dancer and choreographer Trish Sie, to help. “We brainstormed on how to ratchet it up a notch. It had to be some sort of systems thing,” Damian told me at that Soho House meeting in 2006. “The floor had to be moving,” Tim chimed in. Damian added: “She came up with the treadmill idea.”

You may remember OK Go’s treadmill dance to their song “Here It Goes Again.” One camera; one take. The band had to do a crazy, injury-waiting-to-happen dance perfectly. The video exploded on the then-nascent YouTube. Damian got booked on The Colbert Report and The Tonight Show. Sales of the band’s music took off. Concerts sold out. “It fits YouTube like a glove,” author Henry Jenkins told me at the time. “It has an authenticity that comes from being slightly crudely made. It feels like it’s from the bottom up, which is hard to pull off.”

In October 2006, Google bought YouTube for $1.7 billion. My November 28, 2006, story about OK Go closed with this quote from Damian: “YouTube got sold for a few billion dollars, and we are their poster children. The dots connected.”

This is where the part about the adjacent possible comes into play.

In 2010, Steven Johnson published the book Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation. It’s a study of the patterns throughout history that lead to an explosive moment when an innovation – such as the pencil, flush toilet or battery – catches fire and changes the way we work or live.

To describe that moment, Johnson borrowed the concept of the adjacent possible from biology and modified it for his purposes. Johnson divides innovations into two categories: the possible and the not-yet-possible. The possible are things that already exist and work and are understood and adopted by the market. The not-yet-possible are, essentially, lab experiments and dreams – technology that doesn’t yet work well and that the broad market hasn’t adopted.

The adjacent possible is the thin band between these two zones. Innovations change the world when they land there. Such innovations stretch the possible beyond where it’s been before, but not so much that the technology doesn’t work or we can’t understand it.

I believe that in 2005-2006, OK Go’s video stunts landed smack dab in the adjacent possible. Before that time, those videos had no place to go. MTV probably wouldn’t have aired them – they weren’t polished enough. But then YouTube appeared, creating the first platform where home-grown videos like OK Go’s could do something that had never happened before: “go viral.”

If OK Go had made those videos a few years earlier, the videos might’ve just been something that got passed around among friends and family. A few years later, and they might’ve gotten lost amid the many other videos on YouTube. But, by accident, OK Go landed on the adjacent possible. It made all the difference.

In the years since, OK Go has embraced its position as the premier video-stunt rock band – a category it created and owns, though it’s a niche category that doesn’t seem to be overly populated. They did a zero-gravity video dance. They built an insanely complex Rube Goldberg contraption that rolled to their tune “This Too Shall Pass.” They created an elaborately choreographed Busby Berkeley-like spectacle while riding tiny scooters. Again, OK Go’s fans know the videos better than the songs the videos feature.

So, now, is all of that why OK Go named their current tour “The Adjacent Possible Tour”? (It’s also the name of the album the plan to release in April 2025.)

Apparently not. I’ve kept in touch with the band’s publicist, Bobbie Gale of 2B Entertainment. So I sent her an email asking about the origins of the tour name. Her colleague, Collin Citron, got back to me with this:

“The Adjacent Possible is a concept by Stuart Kauffman, a biologist who used computer science to figure out how things evolved,” says Kulash. “And he found that small changes create different possible futures in such radically different ways. Stumbling into the world of that reasoning finally made things make sense to me a little bit—that these little universes get created by such arbitrary, small changes.”

Damian was not borrowing from Steven Johnson, but from the original application in biology. Not quite the tech ecosystem version of the adjacent possible. Yet ultimately OK Go’s 2006 breakout is itself an example of the tech ecosystem version of the adjacent possible.

And now? OK Go is highly active on TikTok, where it has 255,000 followers. I bought tickets for its New York stop on The Adjacent Possible Tour and noticed that most of its shows are sold out.

—

Below is the USA Today column I wrote about my visit to EMI, and the cover story I wrote about OK Go a year later. These were accessed through Newspapers.com.

January 31, 2025

DeepSeek, Soviet Software, and Human Nature

So you’ve heard that China’s DeepSeek developed a world class AI on the cheap while using a fraction of the computing power that big U.S. companies rely on, and maybe you’re wondering:

How is that possible?

There are, of course, a bunch of technical explanations. But there’s also a more profound one: human nature.

This is something I learned while writing about Russian software startups in the late-1980s, yet it’s a part of today’s story that U.S. tech leaders and politicians don’t seem to be talking about…but should.

As the Soviet Union broke up at the end of the 1980s, I traveled there often to write about the first capitalistic private businesses sprouting up. By then I’d been covering the U.S. tech industry for a few years, and was particularly interested in finding fledgling Russian software companies.

There were quite a few, and, surprisingly, some of them were solving problems that had been stumping U.S. companies, and doing it with minimal computing power. For example, a Moscow startup called ParaGraph built software that could recognize handwriting much better than anything ginned up in the U.S. When Apple built its Newton hand-held computer (introduced in 1993), Apple contracted with Paragraph because it couldn’t find anything better here.

In my reporting back then, I asked a lot of Russians about this phenomenon. For decades, the West had sealed off the Soviet Union from acquiring the latest computer hardware. Russian programmers, who until the 1990s all worked for state enterprises or the military, told me they had to do their work on clunky, generations-old machines. Yet at the same time, Soviet leaders pressed them to keep up with Western software. Competition with the U.S. was intense, and the Soviets didn’t want to lose.

That’s where human nature came into play. What would you do if you were required to compete with someone who had vastly more resources? Well, you’d have two choices: give up, or get creative. A lot of Russian programmers got creative. They figured out how to do much more with a lot less because they had to.

At first, when the Soviet Union was intact, that creativity mostly just made the programmers’ bosses happy. But when the Soviet system crumbled, a lot of talented programmers left state-run outfits to found or join local software startups. Many quickly found out – sometimes to their astonishment – that they could compete with U.S. software companies by offering good software that required much less computing power.

One such success was Paragraph. Another was ABBYY FineReader, one of the first useful optical character recognition software products. It came out in 1993 and became a global leader in text recognition and document management. Another was the worldwide hit game Tetris. Yet another debuted a little later, in 1997: Kaspersky Antivirus, which for a while was one of the top global antivirus software tools.

Fast-forward to today, and DeepSeek is kind of a sequel to that movie.

We’ve tried to keep advanced computers and chips from China for a long time. In 2022, the U.S. government established export controls to keep chips like Nvidia’s H100 out of Chinese hands. The export controls have been effective. When DeepSeek started working on its AI, it had about 10,000 older Nvidia chips it had managed to pull together. By contrast, OpenAI runs on at least 10 times more processors, and those chips are the most advanced from Nvidia. (At least one source says OpenAI runs on 720,000 Nvidia chips.)

The pressure to compete when you’re a massive underdog fires up creativity. DeepSeek’s programmers were more clever than U.S. programmers because they had to be. With a wealth of computing power, U.S. coders could afford to take more wasteful routes to building their AIs. The Chinese coders didn’t have that luxury.

As for technical explanations, I’m not much help. I don’t know squat about developing an AI. But Wired has a bit about how DeepSeek did it:

DeepSeek had to come up with more efficient methods to train its models. “They optimized their model architecture using a battery of engineering tricks—custom communication schemes between chips, reducing the size of fields to save memory, and innovative use of the mix-of-models approach,” says Wendy Chang, a software engineer turned policy analyst at the Mercator Institute for China Studies. “Many of these approaches aren’t new ideas, but combining them successfully to produce a cutting-edge model is a remarkable feat.”

Is there anything to be learned from the story of Russian software in the 1990s and Chinese AI in the 2020s?

Well, for one, overconfidence is dangerous. That’s a big reason underdogs win, whether we’re talking AI or football.

I read one story about DeepSeek quoting Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei, who has been a proponent of strong export controls to keep the best chips out of China. The story, on Techcrunch, says: “If Trump strengthens export rules and prevents China from obtaining what Amodei describes as ‘millions of chips’ for AI development, the U.S. and its allies could potentially establish a ‘commanding and long-lasting lead,’ Amodei claims.”

But that kind of reminds me of IBM, circa 1980, believing personal computers could never be a threat to its hulking mainframes. Technology that is good enough, much cheaper and much more easily deployed often kicks the ass of technology that is the very best, very expensive and a pain to deploy. (Check out The Innovator’s Dilemma for more on that.)

And also, endless resources are not always a good thing. That’s another aspect of human nature. It too easily leads to waste, laziness, bureaucracy and the classic “too many cooks.”

I’m not saying that’s true at all of the U.S. AI companies, because I don’t know. And it wouldn’t matter anyway if there were no hungry and lean competitors targeting them. But OpenAI has raised around $18 billion. Anthropic, about $7 billion. U.S. AI companies are assembling historically massive computing power. The resources being thrown at AI here are almost beyond imaginable.

And it’s just possible that’s not helping.

–

I wrote quite a few stories for USA Today in the early 1990s about emerging Russian software companies, and they often included something about Russian programmers’ creative use of computing power. This is one short story that focused on that.

January 17, 2025

Baring It All for Linux

In the fall of 2003, I began a column for USA Today like this: “I am naked with Linus Torvalds’ father.”

OK, ahem, so…in 2003 Linus Torvalds was a big deal in the tech world. He grew up in Finland and had created the Linux computer operating system in the 1990s. At the time, Microsoft was the industry superpower in operating systems and made a fortune selling Windows. Linux was the first well-known open source software, which meant no one owned it and any coder could work on it and improve it. Individuals and companies could use it for free.

Linux was a concept that turned the tech industry on its head and generally made Microsoft executives apoplectic.

This made Linus Torvalds a Robin Hood-like hero around the world and a superstar in Finland, which at the time was enjoying a reputation as a peculiar and surprising tech hub. Nokia, once a Finnish lumber and rubber company, had made itself into a world leader in cell phones. Helsinki had an emerging startup scene. Finland was having a moment.

The Finnish government wanted to make sure Americans knew this. So the Finnish embassy in Washington would from time to time invite Finnish political and tech leaders to D.C. and host an event, inviting U.S. politicians, business leaders and the media. As the tech columnist for USA Today – then the largest-circulation newspaper in America – I often got invited. And, being the manic networker that I was in those days, I usually went.

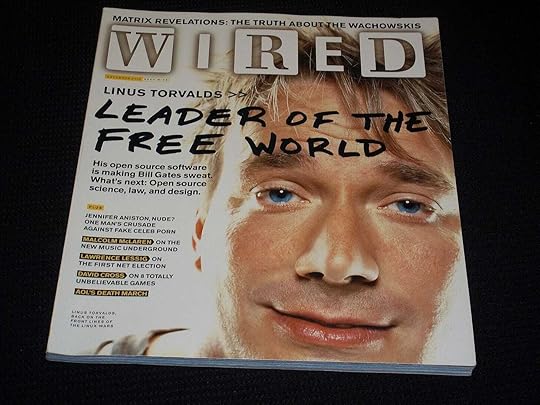

In the fall of 2003, Wired magazine put Linus Torvalds on its cover. The Finnish embassy figured that was a great reason to hold one of its celebratory events. The invitation said that Linus would be there. It also said that everyone would be invited into the embassy’s sauna after dinner.

You don’t get a lot of invitations like that.

This sounded too good to pass up – meet Linus Torvalds, see some of my Finnish friends, and experience the uniquely Finnish tendency to mix business with naked group sweating. As I noted in the column, hanging in a sauna serves a similar purpose in Finland as a round of golf with potential clients does in the U.S. Nokia had a huge sauna in its corporate headquarters. Even small businesses would typically have one.

So, I put on a suit and trekked to the stylish Finnish compound. When I arrived, I found out Linus couldn’t make it. But his father, Nils Torvalds, was there instead. I did not know anything about Nils Torvalds. When we all – maybe 40 or so guests – got ushered to dinner at an elegant long table, I was placed next to him, and we hit it off. Nils, I quickly learned, was a famous television journalist in Finland, and at the time was stationed in Washington covering U.S. politics.

Nils – who I described as “a lanky, athletic man with scruffy, hip-looking facial hair” – turned out to be a fabulous conversationalist, and an out-of-left-field insight into his son. While everyone else was writing about how Linus came up with and managed Linux, I learned about Linus’ origins and pedigree. Nils, for instance, informed me that Linus’ grandfather, Ole Torvalds (also known as Karanko), had been a super famous poet and journalist. In the column I wrote: “Perhaps you've read his Mellan is och eld. No?”

Yeah, me neither.

Anyway, we had a nice dinner, and as it was ending, the hosts announced that it was time for the women to go to the sauna in the basement while the men went to the bar and downed a couple more cocktails. And so, the women disappeared, and I drank with Nils and a handful of American tech journalists I knew pretty well. Maybe 30 minutes later, the women started trickling back into the bar, and it was announced that it was our turn.

Here’s the experience as I wrote about it then:

“The men head down several flights of stairs to what can only be described as a party room — chairs, tables, a wet bar and a dauntingly open space for taking your clothes off, which we do. Next thing you know, I'm sitting in a sauna filled with Finns and rival technology journalists, whom I will never think of in quite the same way again.”

This, as you might have deduced, was when I was naked with Linus Torvalds’ father. Nils hung out nearby and we continued to chat. He handed me birch branches and told me I should flail myself with them. I did not.

I don’t know how long we stayed in the sauna. I know I wasn’t leaving until the Finns did, and I held out. Then we showered, got dressed, and went back to the bar for one last cocktail – always a brilliant thing to do when dehydrated.

Certainly it was one of my more memorable experiences covering technology, and I got a funny column out of it. I never did meet Linus Torvalds, who is still overseeing the Linux community and lately has done things like kick out Russian programmers because of that nation’s war in Ukraine, and offer to build a guitar pedal for a random Linux developer. Linux, by the way, is today on one of the most prominent general-purpose operating systems in the world. Even the Android smartphone OS is based on it.

And Nils? I lost touch with him. Wish I hadn’t. Fascinating guy. Now 79, he got into politics and in 2008 was elected to Helsinki’s city council. In 2012, Nils was installed in the European Parliament, of which he is still a member.

Perhaps someday he and I will schvitz again.

--

Here is the full column as it appeared on October 28, 2003. Unusually, it’s available online.

January 3, 2025

The Innocence of Early Twitter

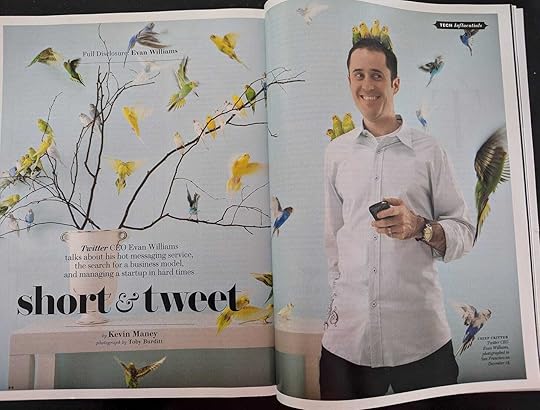

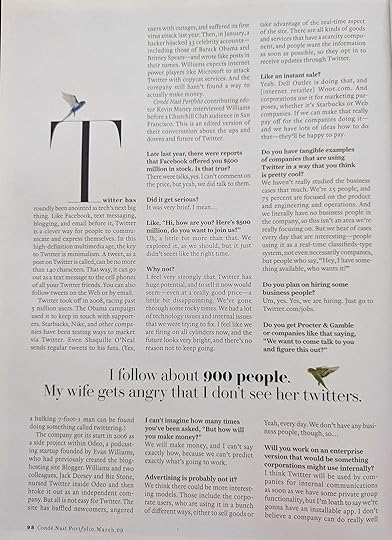

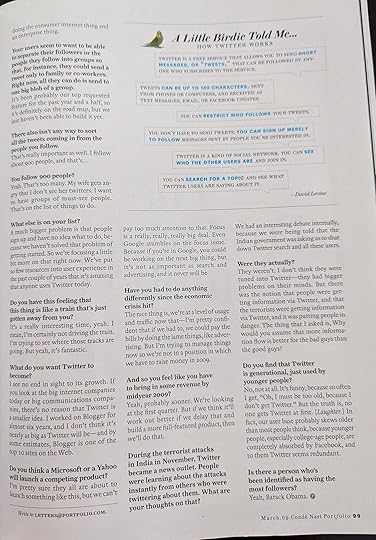

In early 2009, I sat on a stage in San Francisco with Evan Williams, a co-founder of Twitter, and interviewed him in front of about 300 tech peeps who were curious about this new messaging service that Shaquille O’Neal and Barack Obama were using but that mostly featured anybodies firing off bursts about what they had for breakfast or praising their favorite item from Trader Joe’s.

(Tweet’s from my actual 2007-2008 timeline: Mike Hirshland: “checking rss feeds. and doing dishes.” Jeffrey L. Cohen: “Seeing #ironman.”)

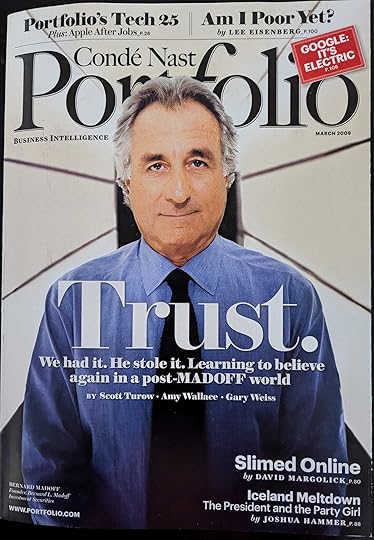

Twitter was so new to most people, when we ran an edited version of the interview in Conde Nast Portfolio magazine (where I was a writer), we had to include a “How Twitter Works” graphic.

Twitter itself didn’t yet know what it was, or why anyone needed it. The company barely knew who was in charge. In 2006, Williams, Jack Dorsey and Biz Stone had all been working on a startup called Odeo, an early podcasting company that Wiliams had founded, Twitter was a side project inside Odeo, built on text messaging – which, on that era’s Nokia and Motorola cell phones with no real screens, was limited to 140 characters.

So, early tweets could only be that long. That was half the fun – finding a way to say something in the length of these last two sentences.

As Twitter started to pile up users, it got spun out of Odeo. Dorsey was its first CEO, lasting two years. Then Williams took charge in 2008, when Twitter had 5 million users. (Stone never got his turn.) Williams told me the company during his tenure employed just 25 people, “and 75 percent are focused on the product and engineering and operations. And we literally have no business people in the company.” Facebook offered to buy Twitter for a reported $500 million. Williams turned down the bid.

The company had no plan for making money. “We will make money,” Williams insisted. “I can’t say exactly how, because we can’t predict exactly what’s going to work.”

Williams was funny and honest and easy to talk to. He mentioned he followed 900 people. To me and the audience, that sounded insane. (Such naive times.) “Yeah, that’s too many,” Williams explained. “My wife gets angry that I don’t see her twitters.” He didn’t call them “tweets” – he called posts “twitters.”

Mostly, Williams came across as still trying to understand what he, Dorsey and Stone had birthed. I’ve rarely run across a tech startup that had so little idea of what it was or where it was going. It solved no pressing problem. I doubt many people sat around in the early 2000s thinking, “Damn, I wish I had a way to send meaningless morsels of information to a lot of people at once.” The founding team released Twitter into the wild and waited to see what people would do with it.

“I’m certainly not driving the train,” Williams said. “I’m trying to see where those tracks are going.”

Around the time Williams and I talked, Apple’s iPhone was changing the smartphone category forever. Screens got bigger and more capable. Phones got real keyboards or keypads. Tweets could get longer and started to be more meaningful – news, promotions, road closures, political messages. Twitter spread globally. Basically, Twitter became the world’s bulletin board. In 2011, it passed 100 million active users a month. A year later, it passed 200 million. In 2013, the company went public on the New York Stock Exchange.

Williams hung on as CEO for two years, 2008 to 2010. Next was Dick Costolo (2010-2105), then Dorsey again (2015-2021), and finally Parag Agrawal 2021-2022).

Of course, most everyone is aware of what happened next. Elon Musk bought Twitter in 2022 for $44 billion. He fired Agrawal and half of the company’s 7,500 employees. In 2023, he renamed it X.

What’s remarkable to me is how innocent and fun Twitter was during Williams’ tenure. In those early days, it could’ve become anything. Over the years, it ended up playing significant roles in history, including events like the Arab Spring and Donald Trump’s rise to political power.

Now, bizarrely, it often seems as if Twitter-slash-X has come full circle, back to not really knowing what it’s good for.

—

This is the interview with Williams as it ran in Portfolio in March 2009. If it’s anywhere online, I can’t find it.

December 15, 2024

We’re Having the Wrong Discussion About Healthcare

At about 9 AM on Dec. 4, I walked down the Sixth Avenue sidewalk right across the front of the New York Hilton hotel. It occurred to me that quite a few cops were casually standing around the entrance and chatting. I thought I heard one of them say the word “shooting,” but, you know, it’s New York. I just kept walking. About an hour later, I first saw the news that UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson had been murdered around the corner, on the 54th Street side of the Hilton, early that morning.

My first thought was similar to what came pouring out of social media soon after: that there are an enormous number of people who would have reason to hate UnitedHealthcare, or any health insurance company. Of course, violence should never be the response to anything. The shooting was a horrific crime. But it’s striking to see how easy it was to imagine the motive.

There’s been a flood of commentary since Thompson’s murder about the need to fix healthcare. Of course it needs to be fixed – our system is frustrating, expensive and bizarre. And yet, most of the commentary seems to be about how to better pay for or manage that same system. (Like: Medicare Advantage for all! Whoopee!)

It’s not the right discussion.

Hardly anyone seems to recognize a superbly simple root problem – which is important, because the problem suggests a solution.

Why do I know anything about this? I’ve played a small role in an effort to try to dramatically change the healthcare experience in ways that stand a chance of making it much better. In 2019, I worked on a book with Hemant Taneja, CEO of VC firm General Catalyst, and Stephen Klasko, who had been CEO of Jefferson Health in Philadelphia. UnHealthcare: A Manifesto for Health Assurance was published in May of 2020. Jefferson is a major hospital system. General Catalyst is probably the single biggest venture investor in health technology companies. It also is in the process of buying an Ohio hospital system, where some of the technology GC has helped fund can be deployed.

The simple root problem we saw is scarcity.

It’s actually a straightforward observation, once you think about it. Healthcare is a very physical, analog industry. There will only ever be so many doctors, nurses, hospitals, clinics, etc. The supply is limited and hard to expand.

On the other side are all of us – and human nature. We all want to be as healthy as possible. No one wants to be sick or hurting. So most of us would consume all the healthcare we could get. Think of it this way: if you had a fully-equipped doctor’s office next door, and you could walk in anytime unannounced and everything was free, wouldn’t you be in there every time you had a cough or a pain or just wanted to be reassured that your blood pressure or cholesterol was OK?

Therein lies the tension. The supply of healthcare is wildly limited compared to the potential demand for it. The gulf between the two is vast.

Health insurers like UnitedHealthcare wind up in the middle of this. Their job is to manage the gulf between supply and demand.

One way they do that is by keeping you from using all the healthcare you’d want – maybe by requiring authorizations, or refusing to cover stuff, or with high deductibles. On the flip side, as economics 101 tells us, low supply and great demand leads to extraordinarily high prices. Health insurers try to manage that by negotiating prices with healthcare providers and, supposedly, protecting individuals from going broke when we need a lot of care. (Whether health insurers manage this gulf responsibly is a whole other discussion. Allowing them to be for-profit creates incentives for them to manage it in THEIR best interests, not in the interests of patients or healthcare professionals.)

Much of what frustrates us about healthcare spins out of the scarcity problem – long waits for a doctor’s appointment, hospitals that charge a fortune even for a bandage, doctors and nurses that get turned into gruff robots because they have to see so many patients in a day. And, of course, sky-high insurance rates.

Now, imagine what might happen if the gap between supply and demand could get dramatically smaller.

Doctors and hospitals would have to compete for your care. Prices would come down and the experience would get better and easier. You’d use routine healthcare more often which would help you stay healthier, and then you’d be less likely to need expensive critical care. Health insurers would have less incentive to get in your way and rates would fall. The nation as a whole would likely be healthier and spend less of its GDP on healthcare.

The problem, of course, has always been the difficulty of increasing supply to the point where it meets demand. That’s because of the physical, analog nature of healthcare.

But here’s what’s different now: new technologies, including artificial intelligence, genomics and robotics, are starting to get good enough to be able to narrow the gap.

When healthcare capabilities become digital, they can be inexpensively scaled. As we noted in UnHealthcare: “Healthcare should be as easy to access as Google Maps. Instead of trudging to a store to pay money for a physical map that can only be printed in limited quantities, every person on earth can tap a phone screen and get a map instantly for free… and that map even has GPS that routes you around traffic jams. It’s time for healthcare to transform from scarcity to abundance through technology.”

How would that work? It’s feasible, for example, that an AI bot could ingest your medical history and have access to the entire universe of medical literature, and act as a kind of pre-doctor app in your pocket. The more you use it, the better it will know you. You’d be able to verbally talk with it, or take pictures or video of that thing on your arm that you want it to look at. It would almost be like that doctor next door, and using it as a health advisor could help you stay healthier or get problems treated sooner, before they get bad and expensive.

Yes, there’s a lot about that to still work out, including privacy concerns and the line between what an AI can advise before it has to refer you to a doctor. (But then, if you need to talk to a doctor, it could happen virtually, making doctors more easily available and cutting down the costs of maintaining doctors’ offices.) But it’s coming. If you want to glimpse an early version of what such technology can become, check out a startup called Hippocratic AI.

Other tech companies are coming at the scarcity problem from many other angles. One of the better known is Livongo, which uses AI backed up by human health professionals to give people with diabetes a kind of personal advisor about their condition. It’s proven to lower the cost of care for people with diabetes while helping them manage their condition and live life better.

This is just beginning, but the promise is real. Already, studies have shown that AI can sometimes diagnose better than human doctors. That’s no rap on doctors – but when faced with difficult, rare cases, AI can search all medical literature ever published. No doctor can know all that. Some surgeries are already performed by robots with a doctor overseeing. Certainly a day will come when robots can autonomously take care of some medical issues, freeing up more of doctors’ time to handle more challenging issues and provide a human touch.

If technology can increasingly handle the more mundane medical care, doctors’ time becomes more abundant. If technology brings inexpensive, easy medical help into our daily lives, more people will stay healthier, which means they won’t need to go to doctor’s offices or hospitals, and that will free up even more healthcare services, so they become more abundant for those who truly need them.

You may think this sounds like science-fiction, but from what I’ve seen, it’s all possible. America will increasingly have the ability to make healthcare more abundant, narrowing the gap between supply and demand.

A lot of entrenched interests will fight it. Policymakers will have to wrestle with it. But ultimately, making good healthcare much less scarce is a more promising way to “fix” healthcare than just trying to better manage our existing system.

—

Here is the first part of the Introduction to UnHealthcare:

In the best of all worlds, healthcare would not exist.

If our bodies and minds stayed healthy until the day we suddenly expired, we would happily do without doctors, pills, hospitals and insurance companies.

The next-best thing would be to have a system designed to help us need as little healthcare as possible – to help us mostly forget about doctors, pills, hospitals and insurance companies. True “health care,” even for the chronically ill, would disappear into our everyday lives, helping us stay as well as possible without having to think too much about our health.

Such a system would be new and different. It would be health assurance.

This is what entrepreneurs and innovators are starting to build: a radically new kind of experience that works as easily as most of our other consumer experiences. It promises to shift healthcare from its current irrational economics to more rational, free-market economics. That shift can drive costs down while improving outcomes – better health, more empathy, fewer mistakes, less frustration.

Everyone wants to “fix” healthcare – even people who work in healthcare. The best way is to encourage hundreds or thousands of new companies and inventions to bloom. That is far better than any program or legislation that only finds another way to pay for our broken, expensive, frustrating healthcare industry.

Healthcare should be as easy to access as Google Maps. Today’s system is built around the concept of scarcity – that there are not enough physicians, hospital beds, medical devices or drugs to go around, so these things have to be expensive and a pain to get. By contrast, most other industries have by now transformed from scarcity to abundance: Instead of trudging to a store to pay money for a physical map that can only be printed in limited quantities, every person on earth can tap a phone screen and get a map instantly for free… and that map even has GPS that routes you around traffic jams. It’s time for healthcare to transform from scarcity to abundance through technology.

It is ridiculous that you have to use a telephone to get a doctor’s appointment two weeks out even though you can buy a car in ten minutes through an app and have it delivered to your driveway. We’ve reinvented commerce, community and content online. Now it’s time to reinvent care.

We need builders and innovators to partner with healthcare professionals to transform the industry so it stops making us conform to it – and instead makes care conform to us. It’s the difference between retailers of the last century making you drive to their stores to look for a product they may not carry, walk their aisles and stand in line at a cash register versus Amazon getting to know you and giving you a personalized store anywhere on any device at any time.

Technology developed over the past dozen years – mobile phones, cloud, artificial intelligence and much more – creates forces no industry can evade, and that includes healthcare. To see the early outlines of a new model, look to startups such as Livongo (an AI-driven model for chronic care), Commure (a platform for medical applications) and some familiar direct-to-consumer companies like Warby Parker (prescription glasses bought online) and Ro (online erectile dysfunction drugs). The richest players in technology – Apple, Amazon, Google,

Microsoft – are investing heavily in this space, and so many more startups and innovations are coming.

This new model will be so different from the old one that we shouldn’t even call it healthcare. That label is tied to the past, and a misnomer. Anyone in the healthcare industry will tell you that they’re really in a “sick care” industry designed primarily to handle people only after they’ve developed problems.

The term health assurance captures the new spirit: easy access to services and technology aimed at ensuring we stay well, so we need as little “sick care” as possible.

Every politician, doctor, healthcare industry executive, employer, entrepreneur and consumer should embrace health assurance, which promises to be more profitable, more efficient, more sustainable and more cost-effective than today’s healthcare – and infinitely better for consumers.

The health assurance space will give birth to ten to fifteen $100-billion companies. The $3 trillion in annual health spending in the U.S. will shrink and be captured by these new companies. The most successful of them will come from creative partnerships between technology companies and professionals in traditional healthcare. The quicker the two worlds merge, the sooner we will stop wasting time on overly-complicated ways to give people access to a fragmented, expensive and inequitable healthcare system.

It’s not productive to blame the vast majority of people in healthcare. They are often frustrated by a system that is fundamentally broken. Most of them want to be part of the solution from inside as entrepreneurs and technologists drive change from outside.

In the Twentieth Century, we built a mass-production model of health care that was right for its time. It scaled up and delivered healthcare to an exploding population, reflecting a fundamental belief in much of the world that even the poorest people should have access to care. That scaled-up model improved the average lifespan in the U.S. from 70 in 1960 to nearly 80 today.

But our model is past its prime and becoming its own worst enemy, and the consequences of not transforming to a new model are dire.

Most debates about healthcare among U.S. politicians talk about the best ways to afford the old healthcare system. But who pays – the government, consumers or employers – is the wrong question. The right question is: How do we enable risk-takers in technology and healthcare to partner and create a transformative approach to lifelong health for all?

Of course, there are enormous obstacles to overcome. But our healthcare system is already in a downward spiral of shrinking margins and exploding costs. Trying to fix it would be like putting a coat of paint on a crumbling building.

Getting there is what this call to action is about, and why we found ourselves working together to start new-era health assurance companies.

##

November 25, 2024

"I write to find out what I think."

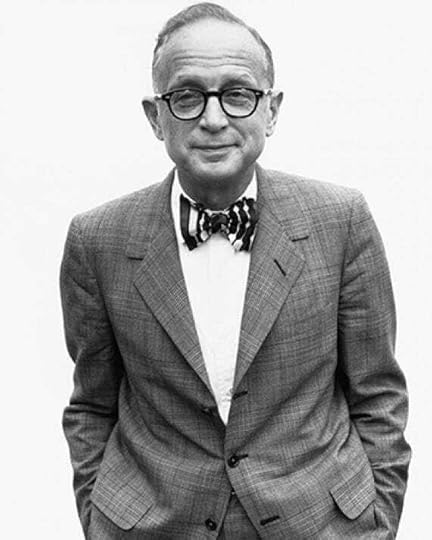

Daniel Boorstin is not exactly a household name. In the 1950s and ‘60s, he was a political historian, author, and professor at the University of Chicago. He wore big glasses and bow ties, and looked like a classic nerdy librarian. And, in fact, in 1975 President Gerald Ford appointed Boorstin as Librarian of the United States Congress – in other words, he ran the Library of Congress.

Early in my career as a journalist, I somehow, randomly, ran across a quote attributed to him. Now, I had never heard of Boorstin and didn’t know anything about him. This was the mid-1980s. There was no internet, no Google. Nobody would’ve posted a Boorstin quote on Instagram. I have no idea how I would’ve run into anything about him.

But when I saw the quote, it spoke to my soul as a young and determined writer. In a few words it described what I loved about writing:

“I write to find out what I think.”

I had the quote printed on a small strip of paper. (Again…how? I didn’t have a computer or printer. Maybe it was one of those old-school hand-held label makers.) For years, I kept that quote taped to my desk wherever I worked.

Now that Google exists, I’ve been able to find out that versions of the quote have also been attributed to writers such as William Faulkner, Joan Didion and even Shirley MacLaine. Actually, if you look on the internet, the quote mostly gets attached to Stephen King, who likely would’ve said it after Boorstin.

So it seems Boorstin riffed on a truth about writing that’s floated in the ether for a long time. The act of writing brings thinking to the forefront and forces you to organize what’s in your head. By organizing it, you make sense of it, and make connections, and sometimes think of something no one else has before.

Today, I find that the quote takes on a fresh meaning in the age of artificial intelligence. In a few words, it describes something uniquely human.

AI can’t write to find out what it thinks.

It can only write based on what others have already thought. AI takes facts and intelligently arranges them in writing based on how others have written. But it can’t take those facts and draw conclusions that nobody ever thought of before. Or write about those facts in an entirely original way.

AI also can’t forge something beyond the edges of what anyone has considered before.

For instance, AI will probably eventually be able to write a Broadway musical that’s much like a classic Andrew Lloyd Webber musical. (Prompt: Write a musical about the 1969 New York Mets in the style of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s “Cats.” I’d go see that! But it won’t break new ground.)

Yet AI can’t be like Lin-Manuel Miranda shaking up Broadway by creating “Hamilton” – a play based on the life of Alexander Hamilton as told through hip-hop music and performed by a multi-racial cast. It can’t conceive, as Miranda did, of something that has no precedent. For now anyway, that takes a human mind.

So, for everyone freaking out about AI, this is our superpower. What’s in our brains are more creative thoughts than AI can generate. But for those thoughts to be valuable, you have to know what they are and have a way to present them to others. That’s where writing comes into play.

Whatever you do for work, it’s important to sit down and write. Find out what’s inside. Take yourself on a journey through what you uniquely know and how you connect ideas and concepts. Creative value will emerge.

It’s an act of discovery that sets us apart from AI.

(By the way, I’m finding out what I think about this by writing about it. So meta.)

October 29, 2024

In 1996, Here's What We Thought the Internet Would Do To Elections

In April 1996, as the election heated up that would put Bill Clinton in the White House for a second term, I wrote a long front-page story about the emerging internet and how it might impact politics.

Here’s the most profound thing that I and most everyone I talked to back then got so wrong:

We all thought people actually wanted to think hard.

And that the internet would help them make more informed voting decisions based on issues and facts.

Ed McCracken, at the time CEO of Silicon Graphics, suggested, as I wrote, that “people may tune out news and ads until a few days before the election, then sit at a PC to sort through the candidates and issues.” Another expert foresaw something called modeling: any voter could enter some personal information on a candidate’s web site and get back specifics of how that candidate’s positions would impact that voter.

“The most obvious effect of the internet on elections will be the amount of information available to voters,” I wrote. “It could help ease one of the biggest complaints about elections: shallow media coverage that focuses on polls, conflicts and personalities.”

Yeah, glad the internet fixed that.

While there were concerns back then that the internet could create problems like making it harder to track political donations, the overall consensus was that the internet would lead to more intelligent voting. “The breadth of visual information and data available will let voters almost feel they know a candidate personally,” I wrote. I quoted David Blohm, who had created software called Vote America, as saying: “Maybe it will take us back to the 1800s, when people made speeches off the backs of trains. It will get a little more personalized, more local, more direct to the voter.”

There was a lot that was difficult to foresee in 1996. The internet then had about 20 million users in the U.S., a tiny sliver of the population. Today, 95% of the U.S. population is on the internet, or about 323 million people.

Most people in 1996 accessed the internet over a modem connected to a phone line – a slow, balky connection that made video nearly impossible. Text and static graphics loaded slowly. Digital transactions were not considered secure, which meant most people would not put credit card information into a site. Contributing to a campaign through the internet wasn’t a thing.

Strangers chatted online on “bulletin boards,” but social media didn’t exist. We didn’t even have blogs yet. The first search engines had just started to appear. No algorithms pushed content to users. Compared to the dystopian Blade Runner city we’ve turned it into, the internet in 1996 was more like a bucolic open prairie.

Sure, there were some inklings in 1996 about what might evolve. “Today, if a candidate wants to tailor a video message to a narrow group, the best he or she could do would be to buy ads on a cable TV channel such as MTV or The Golf Channel,” I wrote. “But on the internet, people join narrow niche groups. At some point, candidates will be able to craft video messages geared to such narrow niches, sending the videos over the internet to the on-line places those people visit.”

But even with that, we were naïve. The people I talked to thought those targeted messages would be about issues.

Almost all the other concerns voiced in the story were about money and politics, but in ways that didn’t really pan out. One thought was that software would allow donations to be tied to a campaign promise. People might release half a donation up front, with other half contingent on the promise being fulfilled. Turns out that was impractical (candidates just want the money up front to win) and would’ve been dangerous (governing decisions could end up being even more influenced by money than they already are).

Looking back from today’s perspective, what went wrong since 1996 is not a mystery. Social networks and digital media increasingly isolated voters in their own echo chambers, amplifying what we already want to hear and cutting out what we don’t want to hear. Creators of algorithms understood that more extreme content gets more attention, and attention in an ad-driven media equates to profits. So, we get served extreme content in our echo chambers, dividing society into us vs. them. Issues become less important than tribalism.

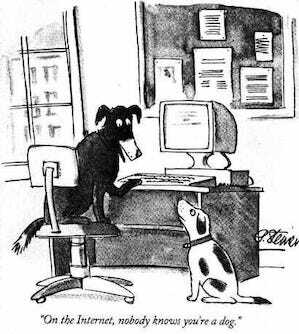

The early internet allowed for an anonymity that at first seemed exciting and freeing. It was in 1993 that The New Yorker published its prescient cartoon showing a dog using a computer with the caption, “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” But anonymity allowed people to be crass, insulting assholes in ways they never would in real life. Decades later, being a crass, insulting asshole has become part of real life, and politics. Donald Trump’s rants seem normal to a segment of the population.

In a different universe, some different decisions along the way could’ve led to different outcomes. If social networks and digital media had always relied on subscriber fees for revenue instead of ads, they might’ve been more responsible about extreme content. If we had always had to be our real selves everywhere online, we might now be less tolerant of asshole-ism.

In 1996, nobody had that foresight. No one I remember talking to was having that kind of conversation. The tech industry was happy to let the internet evolve from a bucolic prairie into a barely-governed wild west.

Now here we are in 2024. The internet is old, but artificial intelligence is new. AI is about where the internet was in 1996, and no one has any idea what impact it will have on politics and elections in the decades to come.

There’s still a chance to make good decisions and get a good outcome. But if history is a guide…we don’t seem to be great at anticipating what might go wrong and proactively stopping it.

Oh, and for what it’s worth, on that same front page where my story ran, the main headline read: “400,000 flee Israeli attacks: Hezbollah warns of retaliation.”

Welcome to The Twilight Zone.

—

Here is the story as it appeared in USA Today on April 15, 1996. It isn’t available online.

October 2, 2024

25 Years Later, I’m Still Not Right

Searchin’ on the Internet looking for love

Screens and screens and screens just keep popping up

Blue cheese, chopsticks, motor oil, French fries

Damn thing knows whatever I’m gonna buy

That’s the first verse of a song titled “Privacy” that I wrote in 2006 and recorded in 2007. I also found a column I wrote in 2000 – nearly 25 years ago – about the idea that people should be able to control, own and sell their personal data, vs. giving it away to web sites.

Throughout these past 25 years, piles of companies have popped up to solve the problem of owning and monetizing our personal data, yet none have gotten traction, most have disappeared, and I don’t know a single person who controls and monetizes their personal data.

In my work with Category Design Advisors, we’re helping a startup right now that’s trying, again, to offer a solution to this personal data issue – this time using AI and other new tools. And it’s not the only new company out there chasing the same problem. This issue has been like watching all the ghost hunter shows pop up on TV. So much time and effort gets spent never actually catching a ghost.

So, you gotta wonder, if a lot of really smart people have been working on this widely discussed problem for a quarter century and no one has nailed it – how come?

I don’t think the issue is a failure of technology or business models. I think it’s this simple: nobody has been able to make most of us care enough to do anything.

It’s like Al Gore setting off alarms about climate change in 2006 and the populace shrugging their shoulders and saying, “Ah, I see your point,” and then going out to buy Hummers.

Here’s the issue as I wrote about it in 2000, quoting Valerie Buckingham, who had recently started a (now long gone) company called MEconomy. “The most valuable thing on the internet in a lot of ways is information about people who are about to buy stuff. But the producers of the most valuable thing on the internet aren’t controlling it.”

Which was true then and is still true now. I continued in the column:

If the producers – who are, ironically enough, consumers like you and me – could gain enough control to charge for their information, web sites would be more judicious about asking for it. Simply taking your information would become stealing.

And in the end, we producer/consumers could make some money. “Years from now, we’ll find it entertaining that people are getting thousands of dollars a year for something they used to give away,” Buckingham says.

By “years from now” she didn’t know she meant, like, in 2030 or 2050.

Yet, if anything, our personal data has become more valuable than ever. And we still don’t get paid for it.

Technology-wise, it’s entirely possible for us to wrap our data – our names, search queries, shopping habits, friends, movie preferences, professional activities and more – in a protective shield as we move through the internet so that web sites and advertisers can’t see it without our permission.

We could choose to sell that permission, with limitations that we set, to web sites and advertisers. They’d buy it in order to better target each of us – in Buckingham’s words, so they could know who is about to buy stuff, and what they are looking for.

It makes sense, but it also adds complexity for consumers. It’s kind of like going from the days when you’d plan a vacation by just walking into a travel agent’s office and telling them where you want to go, vs. finding and booking your own flights, hotels, tour guides and whatever else. Except that we’ve embraced that complexity around travel.

That suggests that adding complexity may not be the real barrier. Instead, the barrier seems to be a deal with the devil we all made long ago – the devil most significantly presenting itself in the form of Alphabet and Meta.

The deal: Alphabet and Meta “buy” our data by giving us free stuff. Google search, Gmail, Google Maps, Calendar, Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp – we find these to be incredibly valuable services, and we get them for FREE!

At least we feel they are free because we don’t actually feel like we lose anything when they siphon off information about us.

It’s a little like free parking on city streets. We all own the streets, so why don’t we get upset when those who own cars get to store them there for free? Probably because we don’t feel like letting them do that costs us anything, even though it does. We’re content to give away what should be valuable space.

The irony is that it’s our data that makes Alphabet and Meta two of the most valuable companies on earth. They learn about us, then sell that information to advertisers that desire to know what we want to buy and when we want to buy it. Those advertisers then improve their profits by selling more stuff with less advertising, thanks to the ads being so targeted. The valuable information we each produce just rolls through the economy adding value to everyone down the line.

And for that, we get Gmail and Instagram.

Oh, and if I were Alphabet and Meta, if consumers started cutting off their data and charging for it, I’d turn around and start charging consumers to use Alphabet and Meta stuff. Would we come out ahead in that trade-off? Hard to say. Alphabet could extort a hell of a lot from me to keep my Gmail account going.

However, I’m old. Al Gore couldn’t get my generation super fired up about climate change, but newer generations are all over it. They are motivated to do something. Similarly, a new generation could very well adopt a very different attitude about their personal data.

They seem to care less about the free digital drugs that Alphabet and Meta serve up. Google search? They’re increasingly going to AI chatbots, which may be training on their inquiries but aren’t taking personal information to sell to advertisers. (At least not yet.) Instead, the chatbots, such as ChatGPT, are getting users accustomed to paying a subscription fee.

Social networking? More and more young people are finding them toxic and intrusive. And more and more would rather text curated groups of friends.

Gmail? Who out there of my generation now has to text their kids to get them to see an email you wrote them because otherwise they’d never look?

So I think there’s a chance upcoming generations will be happy to unwind the deal with the devil and instead want payment for their highly-valuable, worth-protecting personal data.

It took 25 years to get here, but could we be close to people realizing they don’t want what I wrote in the last verse of “Privacy”?

Credit cards, Web sites, ATMs, cell phones

Insurance claims, catalogs, your tab in a barroom

Data data data somehow adds up to me

Now they can predict whenever I’m gonna pee

—

This is my column as it ran in USA Today on May 31, 2000. It’s not available online.

August 20, 2024

You Watch Tech Closely for 40 Years, You See Patterns

I’ve been writing about the tech sector for 40 years. (Y’know, I started when I was 5…) I’ve seen so much up close, but then when I take a few steps back, I sometimes see broad patterns over time. In turn, those patterns help me better understand the new things I see up close.

A few times, I’ve written about those patterns, like in my books Trade-Off and Unscaled (a collaboration with General Catalyst CEO Hemant Taneja), or in articles like one about the adjacent possible.

I just did something similar about a concept I’m calling the “innovation spectrum.” I drew from costly failures I’ve covered, like General Magic, Webvan and, more recently, Humane and its AI pin. And I drew from startups that I watched grow from a seemingly innocuous seed into a monolith — YouTube, Facebook, eBay, Airbnb.

The article below was first published on our Category Design Advisors website. But I think it’s pertinent to this audience. So I’m re-publishing it here.

—

When creating a new market category, an interesting question to consider is: Where will your product land on the continuum from emergent to hierarchical – what we call the “innovation spectrum”?

That discussion can help tell you how to approach investors, what kind of product to build first, how you’ll defend the company against competitors that later come into the category, and a lot more.

The concepts of emergent and hierarchical are more common in biology and physics. But it turns out they can be useful when applied to technology innovations.

I started thinking about this after we, at CDA, got into a conversation with a category design client about what kind of product to build first. The company had a huge vision, but knew it couldn’t create that vision all at once. It decided to begin with a product that would give any early user an immediate “a-ha!” moment.

That discussion, in turn, made me remember a book by Steven Johnson that I’d read 20 years ago, titled Emergence. I dove in and read more about emergence theory, and realized it can be applied in the tech world.

First, an explanation of the terms and their properties as they apply to technology and innovation.

Hierarchical Innovations: The Case of Tesla and Others

At one extreme end of the innovation spectrum are highly hierarchical innovations. These are complex products or services that need to be built completely, according to a master plan, before the first customer gets anything out of it.

One example of that is Tesla. The company had to design a whole electric car, develop an ecosystem of suppliers, build a factory, hire a lot of people, design a way for the cars to get charged, and create a way to sell and service the cars before the first real customer could buy a Tesla and be satisfied with it.

Such a highly hierarchical innovation requires an enormous investment and a lot of time before getting traction. That may sound like a downside, but it can be an advantage. If the innovation is “right” – if it works and the market wants it and the timing is on target – then the amount of investment and time become a big barrier to entry for competitors.

So, a hierarchical innovation that is right can become highly valuable, as we’ve seen with Tesla. Tesla created a new category of electric cars, and got such a head start that it’s likely to own the biggest share of an exploding category for a long time. Investors understand that, which is why Tesla is valued at $724 billion while Ford is valued at $44 billion.

Other examples of successful category-creating, highly-hierarchical innovations include the Boeing 707 (first jetliner), IBM System/360 (first mainframe product line), Apple’s iPhone and ChatGPT.

But here’s the catch: the delta between being right and wrong about a highly hierarchical innovation is huge. Get it right and you could make billions of dollars. Get it wrong, and you might not know it’s wrong for years. By the time the innovation tanks, you’ve lost ungodly amounts of money, time and effort.

Over the years, we’ve seen quite a few of those “getting it wrong” failures in tech. General Magic, Iridium, Teledesic and Webvan are examples. In each case, a vast system had to be built before the first customers could use it. In each case, the technology and timing were wrong, and the company’s implosion left a crater.

Emergent Innovations: From YouTube to Amazon

At the other end of the continuum are highly emergent innovations. These start out simply and can be initially built with a small investment and little time. The first customer can find an early version immediately useful, though in a limited way.

If it’s truly emergent, the innovation has a future to grow into. Over time it attracts more users, developers and partners that continue to add to the innovation and make it more valuable to everyone involved.

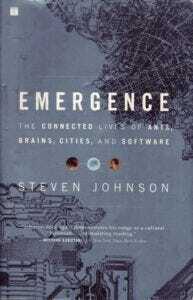

An example of that is YouTube. It was first conceived as an easy way for someone to share a video with friends and family. Before YouTube, sites like Flickr let people share photos, but the same capability didn’t exist for videos. YouTube’s founders, Steve Chen, Chad Hurley, and Jawed Karim, built and launched (in 2005) a beta version in about three months, and the first users started uploading their videos. There wasn’t much to the site.

As more people added more videos and yet more people came to the site to see them, YouTube grew more valuable and robust, over time evolving into a media giant that now includes live TV, full-length movies and people who’ve gotten rich doing nothing but making YouTube videos. (Imagine how hard it would’ve been to build all of that at the outset before letting the first customer in.)

Image credit: Office Timeline 2018

A lot of tech successes have leaned toward the emergent side. Amazon didn’t start by building warehouses and stocking huge numbers of items and creating a vast logistics system. At first it just sold books (which it would buy directly from publishers and rare book dealers) and sent them by mail or UPS (it didn’t need its own logistics system). Facebook started as an online student directory at Harvard. Uber started as an app for hailing a black car in San Francisco.

Highly emergent innovations have their own upsides and downsides for category creators. An upside is that they take little money and time to build, so an idea can get launched quickly with a small team.

But that’s also a downside. If the innovation opens up a category that matters, it won’t take much for competitors to rush in and catch up. Competitive advantage only takes hold once the innovation has attracted so many users, developers and partners that they make the system highly valuable for everyone involved and no one has a reason to go to any competitor.

For a highly emergent innovation, the delta between being right and wrong at the outset is relatively tiny. Get it right and it’s not that valuable at first. Get it wrong, and you’ve only lost a little time and money, and haven’t built anything so complex that you can’t adjust and pivot.

Interestingly, either way it takes years of dedicated work to fully design, develop and win the new category you’re creating.

For a hierarchical innovation, the work takes place out of the public eye and then, suddenly, a full-blown product is ready.

For an emergent innovation, the early product has to iterate bit by bit and add users and an ecosystem, evolving into a robust category-defining product. Everyone involved sees and participates in the progress along the way.

Importantly, this is not bipolar – it’s a spectrum. If you put Tesla at one end and YouTube at the other, there’s a range of possibilities in between. As you move along the innovation spectrum, you dial up and down the various advantages and disadvantages.

Perhaps the innovation you want to build has to be mostly complete before users get value, but it’s not as heavy a lift as building a Tesla or ChatGPT. Spotify comes to mind. It had to build a platform and license a lot of music before early users would find it valuable.

Or you’re creating something that leans toward emergent but requires some robustness before launching. One of our clients, Trainiac, had to build a smart fitness app and also develop a network of personal trainers before getting its first users. It wasn’t a super heavy lift, but it took some time and investment, and so at launch Trainiac had a slight lead over anyone else that might come into its category.

Strategic Considerations for Category Designers

How does all of this influence a company working on category design?

Approaching Investors: Where you land on the spectrum tells you a lot about how much you’ll have to raise before producing revenue. If you’re highly hierarchical, you’ll have to raise a lot and you’ll have to do a lot of work to convince investors you’re right. But show them the payoff once you’re proven right. If you’re highly emergent, get a little funding and get a lightweight product out the door, but make sure you show investors how you can build on that product so it becomes a much bigger business over time. Where you land on the innovation spectrum informs how much to raise, how much runway you’ll need, and how “right” you’ll have to be at the outset.

Product to Build: Many companies know from the beginning whether they are building something hugely ambitious that will take time and money, or a product that can start small and emerge over time. But if you’re an early-stage startup with a monster breakthrough vision that will likely take years to come true, look at options along the continuum. You might find you can quickly get an emergent product out the door, then build on it bit by bit.

Competition: The innovation spectrum can help you know what battles you’ll have to fightt. For a highly hierarchical product, your chief competition is likely yourself – whether you’re right or wrong. If you’re right and an outlier (i.e., no one else has been building the same thing), you could have quite a bit of time before anyone else challenges. Emergent products can be more easily challenged. Category design can make a major difference, because if you do it well, you set the rules for the whole category and convince the public that you know how this category should be built. That makes others who come in follow you, giving you an edge until you gather so much momentum others can’t catch up.

What NOT to do: The innovation spectrum also tells you a type of innovation to avoid: one that is neither hierarchical nor emergent. A lot of stand-alone phone apps fall into this category, like an alarm clock app. It’s relatively simple to build and quickly gives a user satisfaction, so it’s not hierarchical, but it’s also not emergent – there’s not much to build on and lure users, developers and partners. Any innovation that doesn’t seem to be either emergent or hierarchical will likely never win a market category and be valuable. And to state the obvious, the one thing you really don’t want is to work on a very hierarchical product that’s wrong. You don’t want to find yourself five years from now at the bottom of a crater.