Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 295

July 30, 2024

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: July 30, 1956

7/30/1956: Congress enacted a resolution, declaring that the motto of the United States is "In God we Trust." The Supreme Court declined to grant review in Newdow v.Congress, which considered the constitutionality of that motto.

The post Today in Supreme Court History: July 30, 1956 appeared first on Reason.com.

July 29, 2024

[Josh Blackman] Leaks From Moyle

[My speculation was just the tip.]

We are about a month removed from the end of the term, and Joan Biskupic has an exclusive on the deliberations behind Moyle v. United States. Kudos to Joan for getting a scoop, which have been pretty rare the past few years. And she suggests there is a "series," so perhaps we will see Part II tomorrow?

Again, I will offer my usual caveats about SCOTUS reporting. I will assume the Biskupic accurately relayed what was told to her, but I will also assume that the various leaks she received were intended to advance certain interests. In Washington, D.C., information is power, and those who wield it do so to achieve specific goals. Never forget that. There is a reason that President Biden announced his stepping down from the race on X, after having only told a few people. Biden, or at least his team, managed to pull off the impossible D.C. trick: keeping a secret.

For a refresher on Moyle, read my septet of posts (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7).

First, Biskupic describes her sourcing this way:

This exclusive series on the Supreme Court is based on CNN sources inside and outside the court with knowledge of the deliberations.

In the past, Biskupic has attributed her material to a Justice, but here the sourcing is a bit more opaque: "sources inside and outside." We are likely talking about double- or even triple-hearsay. A Justice told something to someone inside the Court, and someone inside the Court told that thing to someone outside the court. Barely two years after Dobbs, the SCOTUS sieve is leaking again. Chief Justice Roberts should dust off that retirement letter.

Second, we learn about how the stay was granted in January. Biskupic reveals the vote was 6-3.

No recorded vote was made public, but CNN has learned the split was 6-3, with all six Republican-nominated conservatives backing Idaho, over objections from the three Democratic-appointed liberals.

To no one's surprise, Justice Barrett was the pivotal vote. At the time, she was persuaded by Idaho's arguments.

[Justice Barrett] would eventually deem acceptance of the case a "miscalculation" and suggest she had been persuaded by Idaho's arguments that its emergency rooms would become "federal abortion enclaves governed not by state law, but by physician judgment, as enforced by the United States's mandate to perform abortions on demand."

But Justice Barrett would later change her mind.

Third, what crystalized the change was the oral argument.

But over the next six months, sources told CNN, a combination of misgivings among key conservatives and rare leverage on the part of liberal justices changed the course of the case. . . .

During the April 24 hearing, signs that the conservative bloc was splintering emerged.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who had earlier voted to let the Idaho ban be enforced, challenged the state lawyer's assertions regarding the ban's effect on complications that threatened a woman's reproductive health. She said she was "shocked" that he hedged on whether certain grave complications could be addressed in an emergency room situation. Barrett's concerns echoed, to some extent, those of the three liberals, all women, who had pointed up the dilemma for pregnant women and their physicians.

In this post, I highlighted how Justices Sotomayor and Kagan set up Justice Barrett's reversal. My speculation closely tracks Biskupic's accounting.

Fourth, Biskupic relays that at conference, there was no clear majority opinion.

The first twist came soon after oral arguments in late April, when the justices voted in private on the merits of the conflict between Idaho and the Biden administration. . . . There suddenly was no clear majority to support Idaho, sources said. In fact, there was no clear majority for any resolution.

As a result, Chief Justice John Roberts opted against assigning the court's opinion to anyone, breaking the usual protocol for cases after oral arguments.

When the Moyle opinion leaked, I wondered who would have assigned the majority opinion. Turns out the answer is that Roberts assigned it to no one.

Instead, as best as I can tell from Biskupic's reporting, Chief Justice Roberts, Justice Kavanaugh, and Justice Barrett jointly wrote the opinion--while trying to keep the votes of Justices Sotomayor and Kagan.

Judging from the public arguments alone, there appeared a chance the court's four women might vote against Idaho, and the five remaining conservatives, all men, in favor of the state and its abortion prohibition.

But at the justices' private vote two days later, Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh shattered any split along gender lines. They expressed an openness to ending the case without resolving it.

Fifth, Biskupic alludes to the various negotiations that happened. In short, Roberts-Kavanaugh-Barrett had to keep Kagan and Sotomayor on board. Why? I'm not entirely sure. In no universe would those two vote to keep the stay in place. So there were always going to be five votes to dissolve the stay. And Kagan and Sotomayor ultimately agreed with only part of the majority opinion. Was that so important? If there were three votes to DIG and three votes to affirm the Ninth Circuit, the end would be the same. Optics matter.

Biskupic writes:

Instead, a series of negotiations led to an eventual compromise decision limiting the Idaho law and temporarily forestalling further limits on abortion access from the high court. The final late-June decision would depart from this year's pattern of conservative dominance. . . . [Roberts and Kavanaugh] worked with Barrett on a draft opinion that would dismiss the case as "improvidently granted."

Biskupic offers some detail on how Barrett reversed herself. Here, she comes off looking extremely open-minded. Moreover, this sort of accounting suggests that she will be skeptical of claims from red-state AGs going forward. I'm not sure who leaked this information, but it is definitely painting Barrett in a particular light:

Barrett had come to believe the case should not have been heard before lower court judges had resolved what she perceived to be discrepancies over when physicians could perform emergency abortions, even if a threat to the woman's life was not imminent. . . . She would eventually deem acceptance of the case a "miscalculation" and suggest she had been persuaded by Idaho's arguments that its emergency rooms would become "federal abortion enclaves governed not by state law, but by physician judgment, as enforced by the United States's mandate to perform abortions on demand." She believed that claim was undercut by the US government's renouncing of abortions for mental health and asserting that doctors who have conscience objections were exempted.

In essence, Barrett, along with Roberts and Kavanaugh, were acknowledging they had erred in the original action favoring Idaho, something the court is usually loath to admit. They attributed it to a misunderstanding of the dueling parties' claims – a misunderstanding not shared by the other six justices, who remained firm about which side should win.

To be sure, Roberts and Kavanaugh changed their minds as well, but they are just supporting actors here. Barrett is on center stage.

During internal debate from the end of April through June, the court's three other conservative justices – Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch believed the facts on the ground were clear and that Idaho's position should still prevail. They said the 1986 EMTALA did not require hospitals to perform any abortions and could not displace the state's ban.

Alito, who had authored the 2022 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization overturning Roe, was adamant that the text of EMTALA required the opposite of what the Biden administration was advocating. He said the law compels Medicare-funded hospitals to treat, not abort, an "unborn child."

Sixth, Justices Alito, Gorsuch, and Thomas come across looking stubborn, obstinate, and intransigent. It seems that that no one supporting this troika talked to Biskupic. That is the problem with inside reporting. Sometimes you only get one side.

With Alito, Thomas and Gorsuch unchanged in their opposition to the proposed off-ramp, Barrett, Roberts and Kavanaugh needed at least two other votes for a majority to dismiss the case.

Two of the liberals, Sonia Sotomayor and Kagan, were ready to negotiate, but with caveats. They disagreed with Barrett's rendition of factual discrepancies and – more crucially – they wanted the court to lift its prior order allowing the ban to take effect while litigation was underway.

This was one case in which liberals, usually holding a weak hand because of their sheer number against the conservative super-majority, had greater bargaining power because of the fracture between the Barrett-Roberts-Kavanaugh bloc and the Alito-Thomas-Gorsuch camp. Debate persisted for weeks over whether the order allowing the ban to be fully enforced should be lifted.

I know Orin, Will, Sam, and most other law professors, disagree with my conception of judicial courage. But you don't have to take my word for it. Look what Justices Alito, Thomas, and Gorsuch wrote in Moyle:

Everything there is to say about the statutory interpretation question has probably been said many times over. That question is as ripe for decision as it ever will be. Apparently, the Court has simply lost the will to decide the easy but emotional and highly politicized question that the case presents. That is regrettable. . . .

Today's decision is puzzling. Having taken the unusual step of granting certiorari before Idaho's appeal could be heard by the Ninth Circuit, the Court decides it does not want to tackle this case after all and thus returns the appeal to the Ninth Circuit, which will have to decide the issue that this Court now ducks.

At the time, I observed:

And why did [Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Barrett] lose the will? The suggestion here is because this case is "emotional" and "highly politicized." Alito implies that Justices Barrett and Kavanaugh changed their minds because abortion is an "emotional" topic and the case has become "politicized." . . . Alito accuses Barrett and Kavanaugh of ducking and hiding for cover.

Alito, Thomas, and Gorsuch ave said the same thing before. And they are saying the same thing I am. The conservative troika has a front-row seat of how Justices Barrett and Kavanaugh behave, and they use their words precisely. To be sure, I think these actions are likely to backfire, in the same sense that Justice Scalia alienated Justice O'Connor. But we should look to these hints from behind the red curtain to figure out how the Justices tick.

Seventh, that brings us back to Justice. Shortly after Moyle was decided, I wrote this about Justice Barrett:

The most important opinion here is from Justice Barrett. She is the Court's center. And, as I've said before, she seems to still be figuring stuff out on the job. Her Moyle concurrence expresses open regret to granting certiorari before judgment and a stay–not just because the facts on the grounds have changed, but that the Court accelerated the process when it shouldn't have. She also seems mad at Idaho for (as she sees it) exaggerating the justification for the stay.

This is almost, to a tee, what Biskupic wrote. I've made this point before: much of the "inside" information that Biskupic gleans from her sources is apparent to those who closely read the Court's docket. I assure you, I have no inside information, and make no effort to obtain any. It is far more fun to shoot in the dark, since I have no limitations on what I can write (as readers well know).

I sometimes wonder if Biskupic begins with really well-informed speculation (what Deadpool might call–spoiler alert–an "educated wish"), passes off that speculation as inside information, and then asks a source to comment or confirm on that apparent leak. From there, the information cascades down.

Finally, Biskupic quotes from Kagan's remarks before the Ninth Circuit Conference.

During a wide-ranging talk at a legal conference in Sacramento on Thursday, liberal Justice Elena Kagan said the court may have learned "a good lesson" from the Idaho case: "And that may be … for us to sort of say as to some of these emergency petitions, 'No, too soon, too early. Let the process play out.'"

In hindsight, this comment comes across somewhere between valedictory and gloaty.

The post Leaks From Moyle appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Venezuela Illustrates the Perils of "Democratic Socialism"

[The Venezuelan experience shows that democracy cannot cure the evils of socialism, and that a democratic socialist system is unlikely to remain democratic for long.]

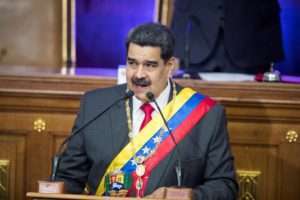

Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro. (Rayner Pena/EPA/Newscom)

Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro. (Rayner Pena/EPA/Newscom)

In yesterday's Venezuelan election, the vast majority of the people wanted to remove socialist dictator Nicolas Maduro from power, but the regime remains in control through a combination of violence and fraud. Venezuela's socialist government has turned what used to be one of Latin America's wealthiest nations into an oppressive hellhole so awful that over 7 million people have fled—the largest refugee crisis in the history of the Western Hemisphere. This terrible experience is relevant to the broader debate over "democratic socialism."

One traditional response to evidence that the USSR, communist China, and other communist states demonstrate that socialism leads to poverty and oppression, is the argument that these regimes failed because they were undemocratic. If government control of the economy is combined with democracy instead of dictatorship, then socialism would fulfill the promise of uplifting the working class. Venezuela's history over the last 25 years undercuts such optimism.

To avoid confusion, I should emphasize that the "socialism" referred to here is government control over all or most of the economy (what Marxists call "the means of production"), not merely having a relatively large welfare state. The latter creates dangers of its own, but not of the same type and scale.

Maduro's predecessor Hugo Chavez first came to power in a democratic election in 1998. For a time, electoral democracy was maintained. But, gradually, the government's control over the economy and centralization of power (itself a requirement of socialism), enabled it to suppress opposition and establish a dictatorship. State control over the economy was a key element of this process. For example, the government used its control over food supplies to suppress opposition. If you oppose the ruling party, you are likely to go hungry. In an economy where there are few or no job opportunities outside the state apparatus, regime opponents also risk unemployment.

Meanwhile, far from uplifting the working class, Venezuelan socialism impoverished them. And that process began even before democracy was fully ended.

In a 2019 piece on "The Perils of Democratic Socialism," I outlined some reasons why democracy cannot cure the flaws of socialism, and why a socialist state cannot remain democratic for long, even if it starts out that way. Here's an excerpt where I highlighted the example of Venezuela:

Perhaps democracy will save us from any potential negative effects of bringing most of the economy under government control…. Any aspiring American Lenin or Hugo Chavez will be voted out of office or—better still—never elected in the first place.

Unfortunately, the democratic element of democratic socialism is unlikely to save us from the severe risks of the socialist part. Voters in democratic systems can and do elect dangerous demagogues. Hugo Chavez was democratically elected.

Closer to home, our own voters elected Donald Trump. And he is far from the first illiberal demagogue who ever achieved political success in American history….

A socialist state that controls most of the economy would also make it nearly impossible for voters to acquire enough knowledge to effectively monitor the government. It would greatly exacerbate the already severe problem of voter ignorance that plagues modern democracy. In a world where most voters—for perfectly rational reasons – do not even know basic facts such as being able to name the three branches of the federal government, it is highly unlikely they will learn enough to properly monitor a socialist state. Most of the powers of government would instead fall under the control of politicians, bureaucrats, powerful interest groups, or worse.

Finally, it is unlikely that a democratic socialist state will actually remain democratic in the long run. If the government controls the vast bulk of the economy, it can, over time, use its control over key resources to reward its supporters and suppress opponents. This has, in fact, actually happened in Venezuela, where the government has used such tools as its control over food resources to incentivize support for the regime, and forestall opposition.

For reasons noted in the 2019 piece, if democratic socialists came to power in the US, it would be harder for them to establish a dictatorship than it was for Chavez and Maduro in Venezuela. But that is in large part because we have more obstacles to the establishment of socialism itself than Venezuela did, such as stronger systems of federalism, separation of powers, and judicial review.

It may still be tempting to conclude that Venezuela's tragedy is the result of defects in their culture or the personalities of particular leaders, such as Chavez and Maduro. But socialist governments have led to similar horrific results in many nations around the world, despite differences in culture and leadership. Either socialism's weaknesses are caused by systemic institutional flaws, rather than local idiosyncracies, or the system tends to elevate awful leaders. Most likely, it's a combination of both.

There are, of course, obvious parallels between Maduro's use of violence and fraud to stay in power after losing this election, and Donald Trump's attempts to do the same after he lost in 2020. One major reason why Maduro may well succeed where Trump failed is that the Venezuelan regime's control of the economy and extreme centralization of power makes it easier for it to suppress opposition. Trump did not control the courts and many other key institutions, and he could not threaten opponents with unemployment and denial of food. Thanks to socialism, Maduro does have these tools of coercion available to him. Fans of democratic socialism would do well to consider whether they want Trump or someone like him to be able to wield such power, should he win an election.

Maduro's regime might yet fall. But it will probably take a mass uprising, large-scale defections by the security forces and regime elites, or some combination of both to make it happen. Socialist institutions make it easier for authoritarians to seize and keep power.

Despite some ideological differences, the "national conservative" policies advocated by Trump, J.D. Vance, and others on the right, pose many of the same dangers as socialism—including the use of state control over the economy to suppress opposition. The difference in slogans and flags between the two movements should not blind us to this underlying similarity.

There is another way in which the Venezuelan experience should give pause to the right, as well as the left. As in the similar case of Cuba, conservatives who rightly denounce socialist oppression should not at the same time try to close America's doors to refugees fleeing it. You can't combat socialism while simultaneously turning your back on its victims.

Like their Cuban counterparts, Venezuelan refugees should not be forcibly consigned to poverty and oppression merely because they had the misfortune of being born to the wrong parents in the wrong place. And, like Cubans, Venezuelan migrants can make valuable contributions to our economy and society—if only we would let them.

In sum, the Venezuelan experience should lead people on the left to reject democratic socialism, if they haven't done so already. For their part, right-wingers would do well to reject similar ideas sailing under the flag of nationalism, and adopt a more welcoming attitude to Venezuelan refugees.

NOTE: I have made minor additions to this post.

The post Venezuela Illustrates the Perils of "Democratic Socialism" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Banana Splits

I appreciate the replies from Orin, Will, and Sam. We have very different conceptions on what role a scholar should play and what role a judge should play. My writings in this area are both retrospective and prospective. I look backwards to see what qualifications a judge had at the moment of their nomination. I also look backwards from the present, to the moment of their confirmation, to assess how those qualifications may have predicted their jurisprudence. I feel fairly confident with my retrospective criticism. A person's pre-confirmation record is their record, and it cannot be changed. And a Justice's decisions are available for all to read. I write more posts about Supreme Court decisions than I care to count.

I, admittedly, feel less confident when making predictions about a judge's future trajectory. My experience with a Supreme Court prediction market has given me some insight into the process, but the Justices continue to surprise me, and everyone else, in ways that are hard to fathom. What loop ties things together? Given a Justice's unpredictability after confirmation, it is of the utmost importance to carefully scrutinize all of a prospective justice's actions before the nomination, and try to extrapolate a trajectory.

And those observations bring me back to Justice Barrett. John McGinnis, for example, favorably compares Justice Barrett to Justice Scalia as a scholar-justice. It is true that they were both academics. But the similarities end there. Justice Scalia was the general counsel at the Office of Telecommunications Policy, chaired ACUS, headed the Office of Legal Counsel, argued before the Supreme Court, worked at AEI, a prominent think tank, spent four years on the D.C. Circuit, and was very much in the mix on all issues of public concern.

I think much the same could be said for other academics who became Supreme Court Justices. Elena Kagan was Solicitor General (briefly), served in the White House Counsel, and was the Dean of Harvard Law School--all experiences that prepared her for the Court. Justice Breyer was a famous administrative law professor, but spent many years working in the Senate on Judicial Nominations, and served as Chief Judge of the First Circuit. Justice Ginsburg, in addition to being a well-regarded professor, was at the heart of the ACLU's women's rights litigation project, and then served on the D.C. Circuit for more than a decade. Jump back a few decades, and look at Justice Frankfurter. He advised FDR, was closely involved in New Deal politics, served as an assistant to the Secretary of War, was a JAG, and served in various other government positions. William O. Douglas was a law professor at Yale, but later headed the Securities and Exchange Commission. Joseph Story was appointed to the Supreme Court at the young age of thirty-two, but by that point he had already been a distinguished member of the Massachusetts Bar, a state attorney for Essex County, Massachusetts, served in the Massachusetts House of Representative, including as Speaker, and was elected to the United States House of Representatives.

Am I missing any other Justices who were academics? We can throw Robert Bork in the mix. In addition to being a law professor at Yale, he served as Solicitor General, worked as Acting Attorney General, survived the Saturday Night Massacre, plus a tenure on the D.C. Circuit.

With the exception of Frankfurter, all of these judges held some sort of apex position, in which they were in charge of making difficult, final decisions. The buck stopped with their commission as an "Officer of the United States." And maybe the Frankfurter nomination is telling. He confounded FDR and other New Dealers by how "conservative" he became. He didn't have a judicial background, and wouldn't you know it, he surprised those who supported him by exercising the utmost restraint. The analogue for Barrett is not Souter or O'Connor, but might just be Frankfurter. A person who lacked the background on the bench, or in a position of power, defaults to caution.

To be sure, Justice Barrett had a tenure on the Seventh Circuit. Barrett's Senate Judiciary Committee questionnaire indicated she participated in the disposition of approximately 900 cases between October 2017 and September 2020. According to Westlaw, Justice Barrett wrote about 80 majority opinions, including a handful of dissents and concurrences. That is certainly the start of a record, but it was fairly brief in telling us much about a judicial philosophy--especially since there were so few cues in her record as an academic. By contrast, Judge Kavanaugh participated in the disposition of 2,700 cases. And, according to Westlaw, he wrote about 1,300 opinions (including majority opinions and separate writings.) The analysis in nine of Kavanaugh's 10 most significant opinions were later adopted by by the Supreme Court. Again, for all of my grievances about Justice Kavanaugh (which have thankfully been fewer of late), he was a known quantity--we knew what we were getting. Ditto for Justice Gorsuch.

What about Justice Barrett's record, knowing everything we know about all Supreme Court justices who came before, would indicate that this person should be a Supreme Court nominee? Her potential was vast, but trajectory was unknowable. This is not to say that Barrett was not a respectable academic. She was. I agree with Will that Barrett chose to spend her time on the things that were important to her. As an academic, that was entirely her prerogative. But the overwhelming majority of all academics (present company included) have not done the things needed to qualify for a Supreme Court seat.

I'm reminded of one of my favorite Scalia stories, which is retold in Ted Cruz's 2015 biography:

Everyone knew that two of the stars on the conservative side, and thus possible nominees, were Robert Bork and Scalia, both on the D.C. Circuit. So one day Scalia was walking in a parking garage at the appellate court when two U.S. marshals stopped him. "Sorry, sir," one of them said. "We're holding this elevator for the attorney general of the United States."

Scalia pushed past them, entered the elevator, and pressed a button. As the doors closed, Scalia shouted out, "You tell Ed Meese that Bob Bork doesn't wait for anyone!"

There are things a Justice does that are not taught in law school.

This topic is perhaps complicated further because so many academics have personal relationships with Barrett–something I don't have. I met her only once, briefly, before she was appointed to the Seventh Circuit. It is difficult to separate the friend you know from the public official they've become. Then again, Justice Kavanaugh served as a guest judge in my high school moot court competition shortly before his nomination. I don't hold back, as you can tell.

As we look forward to the next election, it is important to repeat lessons that have not been learned. A Supreme Court vacancy comes around once in a blue moon. When making the decision of who to select, we must rely on complete knowledge about a person's past practice, and predict the person's likely trajectory. And after the nomination is made, we should be candid and careful to evaluate the decision that was made.

The post Banana Splits appeared first on Reason.com.

[Orin S. Kerr] "Time to Retire the Notion of Judicial Courage," Reprise

[I'm with Sam and Will.]

I share Sam's and Will's basic reaction to Josh's post about the "backbone" of Supreme Court Justices, and I thought I would repost my 2021 take on the whole idea of "judicial courage" from a prior debate with Josh:

Can we simply retire the notion of "judicial courage"? Over a decade ago, I offered this Ambrose Bierce-inspired definition:

The Definition of a "Courageous" Judicial Decision: A judicial decision that stretches the law but nicely matches the observer's policy preferences.

A decade later, that still seems to accurately describe most uses of the term. I mean, I think we get it: When you really want a judge to rule a certain way, or (if they have already ruled) you want to celebrate the judge doing so, it's tempting to clothe that decision in the garb of "courage." Courage, the dictionary tells us, is strength in the face of fear or grief. Describing a judicial decision as "courageous" implies that the judge is a hero for ruling the way you want, and that the only reason they might rule the way you don't want is weakness or fear. This is an easy argument to make within a political culture. It's easy to craft an imagined audience that the Justice is claimed to be afraid of, such that rejecting that imaged audience's view is courageous. But it seems to me that it often resolves to the notion that the courageous thing is to do whatever the speaker wants.

This doesn't mean there are no legal opinions that show courage. In some cases, a judge may feel that the law requires a particular answer that the judge personally opposes and that the judge simultaneously knows will lead to particularly unpleasant personal consequences. This can come up, for example, when a lower-court judge spikes his or her own chance at promotion by handing down a ruling that the judge doesn't like and that significantly hurts their chance at being elevated to a higher court. Consider Judge Jeffrey Sutton's opinion for the 6th Circuit upholding the Affordable Care Act. Given the incredibly successful efforts to make the contrary view the only acceptable GOP view, Sutton's excellent opinion from the standard of traditional conservative judging also ensured he could not appear on a future GOP short list.

But those situations are relatively rare. And as it happens, they're not the kinds of cases that tend to get labeled "courageous" anyway. So on the whole, I think it's probably better to retire the phrase, or at least to be pretty skeptical when it is used.

The post "Time to Retire the Notion of Judicial Courage," Reprise appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Thoughts on Biden's Proposed Supreme Court Reforms

[The proposals include term limits for Supreme Court justices, a binding ethics code, and a constitutional amendment limiting the president's' immunity from prosecution. All 3 are potentially good ideas. But devil is in details.]

(Joe Ravi/Wikimedia/CC-BY-SA 3.0)

(Joe Ravi/Wikimedia/CC-BY-SA 3.0) Today, President Joe Biden announced his support for three reforms: term limits for Supreme Court justices, a constitutional amendment denying the president immunity for crimes committed while in office, and a binding ethics code for Supreme Court justices. He laid out these ideas in a Washington Post op ed. My general reaction is similar to that outlined in my previous post on this topic: all three ideas are potentially good. But Biden is short on details, and term limits can only be properly adopted by a constitutional amendment. As noted in my earlier post, there is also an obvious political dimension to this announcement:

The Supreme Court has become highly unpopular. Currently, it only has an approval rating of about 36% in the 538 average of recent polls, with about 56% disapproving. Targeting the Court might be good politics…. Moreover, if reports about the proposals are correct, Biden has focused on ideas that are generally popular, such as term limits, while avoiding the much less popular (and very dangerous) idea of court-packing.

While I have been highly critical of several of the Court's recent decisions, I also think the conservative majority has many many good rulings, and that much of the left-wing criticism of the Court is overblown. But majority public opinion has a significantly more negative view of the Court than I do, thereby creating potential political momentum for various reforms.

When these ideas were first floated a couple weeks ago, Biden was still trying to salvage his own presidential campaign. Now, they could help bolster that of VP Kamala Harris (who has endorsed them). Josh Blackman is almost certainly right to note the proposals have virtually no chance of being enacted while Biden is still in office. But I think he goes too far in labeling them "pointless." Now that they have been endorsed by the current and future leaders of the Democratic Party, the chance they might eventually be enacted in some form has significantly increased. That's true of any policy idea adopted by one of the two major parties.

Below are a few comments on each of the three proposals.

Here's Biden on the amendment stripping presidential immunity:

I am calling for a constitutional amendment called the No One Is Above the Law Amendment. It would make clear that there is no immunity for crimes a former president committed while in office. I share our Founders' belief that the president's power is limited, not absolute. We are a nation of laws — not of kings or dictators.

I agree. The Supreme Court's badly flawed recent ruling in Trump v. United States goes way too far in granting such immunity to the president. Biden is wrong to suggest that, in the wake of the ruling, "there are virtually no limits on what a president can do." In reality, the decision is vague on several key points, thereby making it difficult to figure out exactly how much immunity it actually gives the president.. Also, there are non-criminal constraints on presidential power (e.g.—people can go to court to get an injunction against illegal executive orders). Still, broad presidential immunity is a bad thing, and enacting a constitutional amendment to abolish all or most of it would be good.

However, Biden tells us next to nothing about the details of such an amendment. I think the version recently proposed by 49 Democratic members of Congress is very good. Not clear whether Biden—and, more importantly, Harris—would support it, or some other approach. In addition, as I previously noted, the odds against enacting any controversial constitutional amendment are extremely long.

Biden on term limits:

Second, we have had term limits for presidents for nearly 75 years. We should have the same for Supreme Court justices. The United States is the only major constitutional democracy that gives lifetime seats to its high court. Term limits would help ensure that the court's membership changes with some regularity. That would make timing for court nominations more predictable and less arbitrary. It would reduce the chance that any single presidency radically alters the makeup of the court for generations to come. I support a system in which the president would appoint a justice every two years to spend 18 years in active service on the Supreme Court.

Here, I have little to add to what I said before. Term limits for SCOTUS justices are a good idea, with broad support from both experts and the general public. A system of 18-year terms is also good, and similar to that proposed by various legal scholars. But any term limit plan must be enacted by constitutional amendment, not merely by a congressional statute. The latter would be unconstitutional, and would set a dangerous precedent, if it succeeded.

Annoyingly, Biden doesn't tell us whether term limits should be enacted by amendment or statute. He also doesn't address the difficult issue of how to handle current justices. Including them in the term limit plan (effectively forcing some to retire soon) would anger the right. Not doing so would likely offend the left.

Biden on a binding ethics code:

I'm calling for a binding code of conduct for the Supreme Court. This is common sense. The court's current voluntary ethics code is weak and self-enforced. Justices should be required to disclose gifts, refrain from public political activity and recuse themselves from cases in which they or their spouses have financial or other conflicts of interest. Every other federal judge is bound by an enforceable code of conduct, and there is no reason for the Supreme Court to be exempt.

Unlike with term limits, Congress has broad (though not unlimited) power to enact ethics restrictions on the Supreme Court. I'm fine with requiring justices to disclose gifts (though there should be an exemption for small ones; no need to disclose every time a friend takes a justice out to dinner or the like). Indeed, I would go further and suggest large gifts should be banned outright. It also makes sense to require justices to "recuse themselves from cases in which they or their spouses have financial or other conflicts of interest." Justices already routinely recuse when there are financial conflicts. However, much depends on what qualifies as an "other conflict of interest." I don't think the mere fact that a spouse has been active on an issue in the political arena qualifies.

As for refraining from "political activity," it depends on what counts as such. Justices should not endorse or campaign for political candidates (to my knowledge, no modern justice has done that). On the other hand, it's fine for them to express views on various law and public policy issues. Both liberal and conservative justices routinely do so in variety of writings and speeches. For example, both Justice Gorsuch and Justice Sotomayor have publicly advocated policies to expand access to legal services. Such advocacy is a useful contribution to public discourse, and should not be banned, though I am no fan of Sotomayor's proposal to impose "forced labor" on lawyers (her term, not mine).

Finally, Biden doesn't say how the ethics code would be enforced, or what the penalties for violations would be. For obvious reasons, those details are extremely important.

In sum, all three of these proposals potentially have merit. But the details matter, and Biden hasn't given us much on that score.

The post Thoughts on Biden's Proposed Supreme Court Reforms appeared first on Reason.com.

:@WilliamBaude: Against Judicial Bravery Debates

I share co-blogger Sam's misgivings about Josh's post assessing the courage of the justices, which I think demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of judicial psychology.

There's a difference between lacking courage, and just not agreeing with your colleagues (or your blog critics) about the right thing to do. I've never seen good evidence that the justices secretly agreed with Josh about the right path in any of these cases and were shying away because of a lack of courage.

Two take two of his examples:

Chief Justice Roberts's infamous vote and opinion in NFIB v. Sebelius have been raked over from every angle, but at bottom, there is not much reason to doubt that he wrote the opinion he wrote because he thought it was the best way to implement his own view about the scope of judicial review in a democracy, implemented through the doctrines of constitutional avoidance, severability, etc. (That's so even if you believe the leaks about the way his vote and opinion evolved at conference, which can more easily be explained on legal grounds.)

The fact that Justice Barrett as a law professor did not write op-eds and amicus briefs or "get into the mix" is also not evidence of lack of courage. It is just as likely that she thought the cases were complicated, had better things to do with her time, or a different view about the vocation of a scholar. Frankly, if more con law professors would get "out of the mix," they would be much better scholars.

Scott Alexander once wrote a post, "Against Bravery Debates," describing the genre of internet argument:

Discussions over who is bravely holding a nonconformist position in the face of persecution, and who is a coward defending the popular status quo and trying to silence dissenters. These are frickin' toxic.

I understand the temptation, and I too have succumbed to it in the past, but I don't think grading the justices on their bravery—especially without evidence that their behavior isn't better explained by thoughtfulness, disagreement, or judicial philosophy—is particularly frutiful or accurate.

The post Against Judicial Bravery Debates appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] President Biden's Pointless SCOTUS Reform Plan

[Three proposals, that lack any specificity, will go nowhere, fast.]

What a difference a fortnight makes. Two weeks ago, Donald Trump was cruising in the polls and President Biden looked to be in jeopardy of losing the nomination. Perhaps as a way to bolster his support among progressives, Biden hinted that he finally was going to propose a plan to reform the Supreme Court. This change was long-simmering, as Biden's SCOTUS commission concluded nearly three years ago. Then, in a flash, things changed. On July 13, Trump survived an assassination attempt by the skin of his ear. Two days, Trump tapped JD Vance as his VP, and the successor of the MAGA movement. On July 19, we got Hulkamania, and Trump gave his RNC speech. Two days later, President Biden dropped out, and VP Harris ascended to the nomination by proclamation. Life comes at you fast.

Here we are, on July 29. And, in an anticlimactic fashion, the lamest duck in modern Presidential history has meekly put forward three suggestions for the Supreme Court that lack any specificity, and will go nowhere, fast.

Biden announced the policy not in the Rose Garden, or on the steps of the Supreme Court, but in a Washington Post Op-Ed. Given the President's communication problems of late, this was probably for the best. The essay is fairly short. It leads with January 6, immunity, and democracy. I know this is a common talking point for progressives, but I'm not sure this point really resonates anymore. That Trump is at least in striking distance of the presidency suggests that all of the talk about democracy the past few years have had no meaningful impact on the populace. I think Barton Swaim's editorial in the WSJ accurately captures how to think about January 6.

It's true that the Jan. 6 riot was a disgrace and an embarrassment to the United States. But Democrats have vastly overinterpreted its political significance. Their belief that it would work as a peremptory argument against a second Trump term was a fantasy.

By the fifth paragraph, Biden finally turns to the Supreme Court, where he sees a "crisis of ethics."

On top of dangerous and extreme decisions that overturn settled legal precedents — including Roe v. Wade — the court is mired in a crisis of ethics. Scandals involving several justices have caused the public to question the court's fairness and independence, which are essential to faithfully carrying out its mission of equal justice under the law. For example, undisclosed gifts to justices from individuals with interests in cases before the court, as well as conflicts of interest connected with Jan. 6 insurrectionists, raise legitimate questions about the court's impartiality.

If there are scandals and crises, where are the articles of impeachment? Has Biden signed onto AOC's proposal? No, of course not. There is no scandal. There is no crisis. Justices took actions that were consistent with the rules at the time. Perhaps Biden thinks those were poor exercises of judgment, but no rules were broken. Biden also embellishes quite a bit. Are Martha Ann Alito's flags "connected with Jan. 6 insurrectionists"? Has Justice Thomas decided any case in which Harlan Crowe was a party? No and no. But really, this is just throat-clearing from Biden. No real substance.

Biden then turns to this three proposals.

First, I am calling for a constitutional amendment called the No One Is Above the Law Amendment. It would make clear that there is no immunity for crimes a former president committed while in office. I share our Founders' belief that the president's power is limited, not absolute. We are a nation of laws — not of kings or dictators.

As all know, a constitutional amendment must receive two-thirds vote from each House, and three-fourths vote of the states. This amendment is a non-starter. It would at least have been useful for Biden to propose some language about what such an amendment would even look like. But he would never do such a thing---or least his OLC would never sign off on it. As unpopular as Chief Justice Roberts's decision is, actually crafting a clear constitutional text for when immunity applies would be extremely difficult. Justice Barrett's concurrence does not fare much better. And the dissenters didn't really try to establish a generally-applicable rule--it was enough that Trump's conduct here lacked immunity. On this point, I would recommend Phillip Bobbitt's sober Just Security essay today. (If I could give a compliment, Just Security, which started off as a more progressive outlet for separation of powers issues, has been starkly more balanced of late than Lawfare, which began as a neutral outlet, but has since drifted away.)

At least with the first proposal, Biden clearly suggests a constitutional amendment is needed. But with the second and third proposals, he leaves the issue open.

The second suggestion concerns term limits:

Second, we have had term limits for presidents for nearly 75 years. We should have the same for Supreme Court justices. The United States is the only major constitutional democracy that gives lifetime seats to its high court. Term limits would help ensure that the court's membership changes with some regularity. That would make timing for court nominations more predictable and less arbitrary. It would reduce the chance that any single presidency radically alters the makeup of the court for generations to come. I support a system in which the president would appoint a justice every two years to spend 18 years in active service on the Supreme Court.

We know a constitutional amendment was needed to impose term limits on the President? Would an amendment be needed for the Justices? Biden does not tell us. He only speaks of a "system." Biden also elides the critical question of whether this proposal would be retroactive, or only prospective. For example, would the current nine Justices be required to retire after 18 years? Or would only new Justices appointed under this "system" be subject to the limit? Or does Biden favor the "panel" approach, in which Justices who have already served 18 years would be forced to take "senior" status and not hear any actual Supreme Court cases? I think that rule is 100% likely to be declared unconstitutional. It should be unanimous. And Biden certainly knows this. Or at least he should know it.

The third proposal cribs Justice Kagan's latest missive, calling on the ethics code to be enforceable.

Third, I'm calling for a binding code of conduct for the Supreme Court. This is common sense. The court's current voluntary ethics code is weak and self-enforced. Justices should be required to disclose gifts, refrain from public political activity and recuse themselves from cases in which they or their spouses have financial or other conflicts of interest. Every other federal judge is bound by an enforceable code of conduct, and there is no reason for the Supreme Court to be exempt.

Biden does not explain how the code would be enforced? Would he assign lower federal court judges to oversee the Supreme Court? I wrote a long post about this issue yesterday, and I won't repeat those arguments here. But I will repeat my prediction of where this proposal may wind up:

I regret that Justice Kagan started down this road. Given that President Biden will soon announce his own Court reform, this issue is on the wall. Once the filibuster is abolished–as Senator Elizabeth Warren has promised–I suspect the Court will be placed under this regime. My other predictions from four years ago may yet come to fruition.

One final point. A number of President Biden's judicial nominees may need a tie-breaking vote from Vice President Harris. Given that she will be busy on the campaign trial, scheduling those tie-breaking votes may prove difficult. Biden's final judge count is still TBD.

The post President Biden's Pointless SCOTUS Reform Plan appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Ohio State Appoints Professor Lee Strang to Direct New Salmon Chase Center

[A strong appointment for an important new initiative at Ohio State University.]

The Ohio State University (tOSU) has appointed Professor Lee Strang as the inaugural Executive Director of the Salmon P. Chase Center for Civics, Culture, and Society. This is good news. Professor Strang is an excellent choice for this position.

From tOSU's :

The Ohio State University has appointed legal scholar Lee J. Strang as the inaugural executive director of the Salmon P. Chase Center for Civics, Culture, and Society. Strang is the inaugural director of the University of Toledo's Institute of American Constitutional Thought & Leadership and currently serves as the John W. Stoepler Professor of Law & Values at the University of Toledo, where has been a member of the faculty since 2008.

Lee J. Strang

"Lee is an exceptional constitutional scholar with a wealth of administrative experience, and we are excited that he will join the university to stand up and lead the new Salmon P. Chase Center," said Karla Zadnik, interim executive vice president and provost. "Our shared goal is for the center to become a national leader in teaching, research and engagement on U.S. civics, culture and society."

Initiated in 2023 by the state of Ohio, the Salmon P. Chase Center will be an academic home at Ohio State for teaching and researching the foundation of the American constitutional order and its impact on society. As executive director, Strang will be responsible for organizing the center, overseeing the hiring and appointment of the center's faculty, developing curriculum and delivering academic programming.

Professor Strang is a strong scholar, a dedicated teacher, and someone who commits himself to the institutions of which he is a part. I look forward to seeing what he builds at the Chase Center.

The release also says this about the Chase Center:

When it is fully operational, the center will have at least 15 tenure-track faculty members and provide a variety of innovative educational and collaboration opportunities for students and faculty from across the university. The center will be an independent academic center physically housed in the John Glenn College of Public Affairs. . . .

The Chase Center academic council led the nationwide search for the executive director. The academic council members are scholars with national reputations for academic excellence and come from Ohio and universities across the nation.

[Note: Why "tOSU" instead of "OSU"? Well, if it's "the Ohio State University" then tOSU reflects that fact.]

The post Ohio State Appoints Professor Lee Strang to Direct New Salmon Chase Center appeared first on Reason.com.

[Samuel Bray] Banana Republican

I found myself disagreeing with some of the points made in co-blogger Josh Blackman's post this morning entitled "I could carve a judge with more backbone out of a banana." Instead of a point-by-point rebuttal, here is a set of more general observations:

Law is not like the game of Risk, a game of global domination. No legal principle will yield you all the results you want, and principled judging will never yield total domination for any political party or ideology. Anyone who expects that will be disappointed. The line taken on Justice Barrett bears no resemblance to her actual body of work on the Court so far, which is absolutely sterling, regardless of whether you agree with her on the outcome of any given case. Here, for example, is a more cogent analysis by John McGinnis. The suggestion that what we need in Supreme Court nomination hearings is more "courage" in an idiosyncratic sense (n. courage, 1a "owning the libs") is exactly wrong. Yes, courage is a virtue, but like most virtues it is not reducible to performative spectacle. Supreme Court nomination hearings have already moved too far in the direction of cable news meets WWF. That is a progression to arrest, not to pursue as if it were the path of enlightenment. When we evaluate the work of the justices, I am almost tempted to say we should care more about their opinions than their votes. The votes matter, of course. But in current practice, and especially when so few cases are being decided by the Court, it is the rationale and argument expressed in the opinion—with its craft or absence of craft, and its principle or absence of principle—that drives the development of the law. To treat judges as fundamentally being vote-casting officials is a symptom of treating them as legislators. For legal scholars, there is value in analysis that does not fully collapse into the analyst's perspective on the merits. We should be able to make analytical claims about what the justices are doing—critical, sympathetic, both, whatever—that stand on their own apart from whether the author thinks the Court is right on the merits. Otherwise we run the risk that our legal analysis will shade into station identification and more cowbell.The post Banana Republican appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers