Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 292

August 6, 2024

[Josh Blackman] United States v. Abbott and State War Powers

[A guest post from Professor Rob Natelson.]

Last week, the en banc Fifth Circuit resolved the buoy case. I am happy to pass on this guest post from Professor Robert Natelson, who co-authored an article on the war powers of the states.

—

On July 30, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled that the district court should not have granted the United States a preliminary injunction ordering Texas to remove a barrier lying in the Rio Grande River. The case was United States v. Abbott, and it was decided on the issue of navigability. However, the case also has implications for states' power to wage defensive war—and particularly defensive war against illegal immigration.

Andrew T. Hyman and I recently published an examination of those issues in the British Journal of American Legal Studies. We focused mostly on Founding-era evidence of the kind probative of the Constitution's original meaning. Our article played a role in the case—but, as described below, a rather unusual one.

The Parties' ContentionsThe State of Texas had placed a 1000-foot floating barrier in the Rio Grande near Eagle Pass, Texas, a busy border-crossing area. The state justified the barrier by invoking state war powers to stem an "invasion."

The U.S. government claimed that Texas's power to respond to the alleged "invasion" had expired. The government also maintained that the state right of self-defense had been qualified by the congressional Rivers and Harbors Appropriation Act of 1899, which forbids obstructing navigable waterways without federal consent. (The Constitution grants Congress jurisdiction over navigable waterways as a component of the Commerce Power.)

Texas countered that under traditional navigability tests, the Rio Grande was not, and never had been, navigable above the city of Roma, Texas—far downstream from the Eagle Pass floating barrier.

State War PowersThe Constitution granted federal officers and entities, as well as the government itself, certain enumerated powers. As confirmed by the Tenth Amendment, it reserved the remainder to the states and the people. Moreover, where the Constitution did not specify that federal authority was exclusive, the states retained concurrent, although subordinate, jurisdiction.

Among the concurrent powers reserved to the states was the prerogative of making war. However, Article I, Section 10, Clause 3 limited that prerogative considerably:

No State shall, without the Consent of Congress . . . keep Troops, or Ships of War in time of Peace . . . or engage in War, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay.

In international law terms, Congress could authorize state participation in offensive war. But states retained unconditional power to wage defensive war.

As our study pointed out, this clause retained a balance between federal and state war-making that was approximately the same as that prevailing under the Articles of Confederation.

But only approximately. The Constitution added one further constriction and four expansions of state war powers. Specifically, the Constitution (1) denied state power to issue letters of marque and reprisal—an additional restriction on offensive war but (2) discarded the former limitations on states' ability to wage defensive conflicts.

The Constitution also granted the federal government supreme power to regulate immigration (Article I, Section 8, Clause 10). However, states also retained subordinate concurrent power over that subject. This was recognized in the portion of Article I, Section 9, Clause 1 that referred to free migration as opposed to the importation of slaves: "The Migration . . . of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit . . . .".

Mr. Hyman and I investigated the Founding-era meaning of "invasion" and "invaded" to determine if, as three U.S. appeals courts have opined, those terms were limited to formal attacks by foreign military forces. We found they certainly were not. Both 18th century dictionaries and contemporaneous usage supported definitions broad enough to encompass peaceful but unauthorized cross-border incursions that resulted in damage. For example, in the years before the Constitution was written, both Benjamin Franklin and Pennsylvania officials referred to a peaceful but unauthorized wave of immigration into their state as an "invasion."

We also learned that during the Founding era, migrants entering a country illegally were considered, or treated as, "alien enemies." They were not accorded the same rights as "alien friends." It made no difference whether an illegal migrants' country of origin was friendly or hostile.

Finally, we examined Founding-era international law to determine the sorts of tools a sovereign may use to fight a defensive war. Not surprisingly, these included barriers to thwart invaders.

So based on our findings, it appeared that Texas was on sound constitutional ground when invoking its defensive war powers to justify building a barrier—at least until one considers the Rivers and Harbors Appropriation Act.

The Court's DecisionUnder that law, if the Rio Grande is "navigable" at the point where Texas constructed its barrier, then a conflict arises between congressional exercise of the Commerce Power and state exercise of defensive war powers.

In United States v. Abbott, the court avoided that conflict. In an opinion written by Judge Don R. Willett, the court concluded that the Rio Grande was not navigable in the area of the barrier, because the river above the city of Roma had never been a "highway of commerce." Although there was some evidence that a ferry had crossed the river near Eagle Pass, Judge Willett held that ferries crossing rivers merely cover gaps in land routes. A ferry may indicate that a lake is navigable, but "Lakes are obviously not rivers."

Chief Judge Priscilla Richman concurred in the decision, but would have left open the possibility that adequate proof of a ferry route could show navigability.

Judge Ho's OpinionJudge James C. Ho wrote a concurring-and-dissenting opinion focusing on the state right of self defense. He argued that the U.S. government's request for a preliminary injunction should have been dismissed because when a state, in good faith, claims it has been invaded and invokes its war powers, the legality of its decisions are non-justiciable political questions:

Supreme Court precedent and longstanding Executive Branch practice confirm that, when a President decides to use military force, that's a nonjusticiable political question not susceptible to judicial reversal. I see no principled basis for treating such authority differently when it's invoked by a Governor rather than by a President. If anything, a State's authority to "engage in War" in response to invasion "without the Consent of Congress" is even more textually explicit than the President's.

In Judge Ho's view, however, "good faith" decision making is a prerequisite to non-justiciability. In this respect and in some other respects, his analysis is similar to ours. We wrote:

"Insurrection" and "invasion" not only trigger the federal government's duty under the [Guarantee] Clause, but also trigger exercise of state war powers. If the terms are too vague for courts to define for federal purposes, then they also are too vague for courts to define for state purposes. If [Guarantee] Clause cases are held to be non-justiciable because the Constitution commits the decision of whether and how to protect states against invasion to the political branches of the federal government, then the Constitution even more clearly commits (as demonstrated by the Self-Defense Clause) the determination of whether a state has been "Invaded" or in "imminent Danger" to the state government. If redressibility issues impede justiciability in [Guarantee] Clause cases, then they could also impede justiciability when a state has gone onto a war footing and raised an army.

To be clear: If federal officials are proceeding in good faith to crush an insurrection or repel an invasion, the courts should not second-guess their tactics. But judicial intervention is appropriate when federal officials utterly neglect their duty or adopt measures so plainly insufficient as to demonstrate a lack of good faith effort.

Judge Ho's concurrence matched our conclusions in another respect as well: Both he and we doubted whether a federal law, even if clearly contradicting the right to state self-defense, could take priority over that right. ("[F]ederal statutes," he wrote, "ordinarily must give way to federal constitutional rights.") This makes sense: Self-defense is inherent in sovereignty, and the Supreme Court has defended less important aspects of state sovereignty from otherwise-valid congressional action. Examples include the protection of a state's decision on where to locate its capital and protection of state officials from federal "commandeering."

Judge Andrew S. Oldham also concurred, primarily to dispute Judge Ho's foray into constitutional issues. Judge Oldham rested his conclusion solely on a finding of non-navigability.

The DissentsIn his dissent, Judge Stephen A. Higginson argued that the federal government should be able to rely on ferry traffic across a river to prove the river's navigability.

Judge Dana M. Douglas's dissent challenged the majority's evidentiary conclusions on navigability, maintaining that the federal government had presented ample evidence that the Rio Grande near Eagle Pass qualified as navigable. She also concluded that once Congress has an opportunity to respond to an invasion, state war powers cease:

Clause 3 provides that a state may engage in war without consent of Congress only when it is "actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay." . . . See, e.g., Articles of Confederation of 1781, art. VI, para. 5 (limiting a state's power to engage in war "till the united states in congress assembled can be consulted"); Robert G. Natelson & Andrew T. Hyman, The Constitution, Invasion, Immigration, and the War Powers of States, 13 Brit. J. Am. Legal Stud. 1, 17 (2024) (noting that, in regard to state war powers, the Constitution resulted in "a balance between federal and state prerogatives roughly similar to that under the Articles of Confederation") . . . .

In other words, because the scope of state war power under the Constitution is roughly equal to the scope under the Articles, and because the Articles required consultation and/or consent by Congress, then state war power under the Constitution is similarly limited.

Unfortunately, the publication she relied on—ours—directly contradicted her conclusions. We wrote that under the Articles of Confederation, states "retained virtually unlimited flexibility to engage in defensive land war—even after Congress had been consulted—except for power to strike pre-emptively at non-Indian enemies."

More importantly, we found that the Constitution had removed the Articles' constraints on state defensive war:

[O]n the land side, the Constitution preserved general state control over their militias while providing that "No State shall, without the Consent of Congress . . . keep Troops . . . in time of Peace . . . or engage in War, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay." This limitation omitted the Articles' contingent requirement of consultation with Congress. (Italics added.)

We have written to Judge Douglas advising her of the discrepancy.

####

Rob Natelson is senior fellow in constitutional jurisprudence at the Independence Institute in Denver and a former constitutional law professor at the University of Montana. He is the author of "The Original Constitution: What It Actually Said and Meant" (3rd ed., 2015).

The post United States v. Abbott and State War Powers appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Lawsuit Over Alleged Discriminatory Refusal to Let Church Lease School Property on Weekends Can Go Forward

From Pines Church v. Hermon School Dep't, decided last week by Chief Judge Lance Walker (D. Me.):

Plaintiffs The Pines Church and its lead pastor, Matt Gioia, looking for a new space to accommodate their growing congregation, requested a twelve-month lease to hold Sunday services at Hermon High School. The Defendant Hermon School Department's School Committee, after meeting and discussing the challenges associated with such a relationship, did not make a motion to vote on the requested twelve-month lease. Furthermore, the Committee members refused to second a motion to vote on a six-month lease. Ultimately, the Committee voted to offer Plaintiffs a month-to-month lease.

Plaintiffs filed this civil action, alleging that the School Committee's refusal to extend a long-term lease was motivated by animus against their sincerely held religious views …. The School Department offers a competing characterization of events, maintaining that the School Committee's decision was influenced by concerns about entering into a long-term lease agreement.

Before the Court are the parties' competing motions for summary judgment. Plaintiffs rely on the relatively blatant bias and the inferences that arise from the interrogatories posed by one Committee member who demanded to know from Pastor Gioia the Church's "position" on a spate of religious, political, and cultural flashpoints before evaluating whether to extend a lease on behalf of a publicly funded school.

Plaintiffs also rely on a somewhat more tepid bias, sanitized through fear-of-association comments by others, along the lines that association with the Church may not fit with the Committee's "goals" and may therefore create a "negative image" by not comporting with the School Department's "mission" and evidently its own beliefs. This evidence certainly is probative of Plaintiffs' position that the School Committee's refusal to offer Plaintiffs a lease was motivated by unconstitutional considerations, such as animus toward the Church's orthodox religious beliefs.

For its part, the School Department counters that the School Committee's decision, save for the one Committee member's bill of particulars put to the Pastor, simply resulted from humdrum, benign space and cost concerns, although that narrative is far from conclusive based on the summary judgment record. These competing characterizations of the Committee's motivations form the most conspicuous reason I deny summary judgment to the parties in favor of a jury trial.

More on the facts of the case:

At the November 7, 2022, School Committee meeting, Gioia gave a presentation to the Committee. To signify the Church's intent to invest in the Hermon community, Gioia offered to pay $1,000 per month, which was $400 more than the School Department's proposed monthly rent.

The following day, School Committee Member Chris McLaughlin emailed The Pines Church and explained that he had "a few follow-up questions for" Gioia "that occurred to [him] after the presentation." Gioia responded, asking that McLaughlin funnel his questions through Superintendent Grant. McLaughlin emailed Superintendent Grant and wrote that he wanted to get a better sense of how the Church "approaches issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion" and "[the Church's] messaging around some key issues relevant to marginalized communities." McLaughlin was "curious" about whether "the Pines Church" is "receptive of same-sex marriages?" He asked if "they consider marriage only to be between 1 man and 1 woman?" "In addition to" his "question on marriage," McLaughlin was "wondering if" Pastor Gioia "can share more information on where the Pines Church stands on" the following issues:

"Access to safe and affordable abortion"; "Access to gender affirming medical care"; "Conversion therapy for LGBTQIA+ individuals (youths and adults)"; and "Inclusive sexual education and access to birth control for youth."On November 10, Superintendent Grant forwarded these questions to Pastor Gioia, who did not respond. There is no evidence suggesting that other Committee members were involved in McLaughlin's inquiry or knew about it.

On December 12, 2022, the School Committee met to consider the Church's lease request. The parties offer competing narratives of what was said during this meeting.

Plaintiffs claim that one of the Committee members questioned how the lease would "fit" with the "Committee's 'goals'" and that Hermon High School Principal Brian Walsh and other Committee members commented that the School Department's association with the Church might create a negative image. According to Plaintiffs, Principal Walsh insinuated that the School Department could not associate themselves with the Church because its religious and political beliefs do not align with the School Department's mission and apparently its conflicting beliefs. Lastly, Plaintiffs assert that the Superintendent and the Committee members did not identify any scheduling conflicts with Plaintiffs' requested lease. The School Department refutes this description.

The parties agree that the Committee members [also] discussed school-sponsored activities taking priority, space in the parking lot, and staffing issues, including the need to have the high school space cleaned on Sundays….

And some excerpts from the court's analysis:

The School Department places great weight on the undisputed fact that the School Committee offered Plaintiffs a month-to-month lease. From there, the School Department reasons that a jury could not find that the Committee's refusal to offer a lease was based on improper considerations since the Committee was willing to enter into a month-to-month lease agreement with Plaintiffs.

In the context of the School Department's Motion, the record must be viewed in the light most favorable to the Plaintiffs' cause. A reasonable jury could find that the Committee's unwillingness to enter into a twelve-month lease agreement with Plaintiffs, evinced by none of the Committee members being willing to even second the motion to offer a six-month lease, was based on impermissible considerations, such as a fear of association, which Principal Walsh and other Committee members allegedly expressed. In short, whether the Committee members acted with improper motives when considering Plaintiffs' lease request remains in dispute, so the School Department's Motion is denied.…

{Evidently, the parties have conducted discovery and filed their competing Motions without considering exactly what must be proved under § 1983 to support a finding of unconstitutional municipal action. With the discovery process having closed in December 2023, the examination into the Committee members' subjective motives is over outside of calling them as witnesses at trial. Having not addressed the requirements of § 1983 …, both parties' analyses regarding Plaintiffs' constitutional claims are incomplete and fatal to their attempts to resolve this case short of trial….

In any event, Plaintiffs have come forward with enough evidence such that the accompanying reasonable inferences yield a genuine factual dispute as to whether the School Committee's decision was based on an impermissible motive. Plaintiffs' case does not solely rely on McLaughlin's questions, which, as the School Department conceded at oral argument, give rise to an issue of fact of whether McLaughlin had an improper motive. Additionally, Plaintiffs assert that "one committee member said that leasing to the Church did not fit the Committee's goals," and that Principal "Walsh even insinuated that" the School Department "could not associate themselves with the Church because their religious and political beliefs do not align with" the School Department's "mission." Lastly, Plaintiffs claim that "[o]ther committee members and Principal Brian Walsh made discriminatory comments about the Church by suggesting" that the school's "association with the Church and its religious beliefs would create a negative public image." Plaintiffs do not identify which School Committee members made these statements or how many School Committee members in total made similar statements, but at least three School Committee members are implicated. This is just shy of a majority, but it suggests that "at least a significant bloc of" the Committee members may have acted with improper motives. Furthermore, based on Plaintiffs' assertion that Walsh—the Principal of Hermon High School—made discriminatory comments by suggesting that associating the high school "with the Church and its religious beliefs would create a negative public image," it is possible that other Committee members might have been influenced by Walsh's comments. Moreover, a jury could consider whether Plaintiffs are similarly situated to the organizations that use—but do not rent—school facilities in evaluating the veracity of the School Department's asserted reasons for declining to enter into a long-term lease with Plaintiffs.}

{The School Department's proffered transcript of the meeting (which was offered in opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion, but not in support of the School Department's Motion) might corroborate Gioia's recount of the meeting. According to the transcript, McLaughlin asked how the lease "ties in with the [Committee's] goals" and how the lease would "bolster" the community. Committee member Eva Benjamin asked whether the Church would "use the high school's address" to advertise and promote the Church, and after Superintendent Grant answered yes, she asked if "that would create any confusion or conflict in the community." When asked about possible scheduling conflicts with school-related activities, Principal Walsh said: "If you put our high school's name with a church or another organization with different beliefs than the school has, I see that as a problem we're having."

McLaughlin asked Principal Walsh about whether students expressed any opinions about the lease, and Walsh responded that "a number of students" asked him "'Why would we have the church if we don't own that church? Are they going to use Herm[o]n High School's name? What if we disagree with their mission?'" Committee Member Haily Keezer did not "see how them using the address so people can find it has anything to do with affiliation with the school," and she said, "So it sounds like what you're saying is, you don't want them to say, 'Herm[o]n High School.' You don't want them to associate with that." Principal Walsh said that he did not "want it looking like Herm[on] High School is sponsoring a church. That's where—again—this is where the blur comes in. So again, that's something you guys ensure."} …

Nothing in the Constitution prevents the School Department from deciding that they will not enter into any long-term lease agreements. But once the School Department has opened itself up to possible lease agreements, it cannot turn a religious group away simply because of its religious character. Thus, the question here is, as I have explained above, whether the Committee acted with improper motives when declining to extend Plaintiffs a long-term lease agreement, thereby penalizing religious activity.

The post Lawsuit Over Alleged Discriminatory Refusal to Let Church Lease School Property on Weekends Can Go Forward appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] D.C. Circuit Strikes Down Automated Filtering of Supposedly "Off-Topic" Comments on NIH Site

In last week's People for Ethical Treatment of Animals v. Tabak, the D.C. Circuit (in an opinion by Judge Bradley Garcia, joined by Judges Karen LeCraft Henderson and Patricia Millett), held that NIH's automated filtering of comments on Facebook and Instagram pages was unconstitutional. The filtering was supposedly aimed at blocking "off-topic" posts, but it did so by filtering out words "such as … 'animal,' 'testing,' and 'cruel.'" This was unconstitutional, the court held because a government-agency-run comment section was a "limited public forum," where restrictions on public speech had to be "reasonable in light of the purpose served by the forum" and "viewpoint neutral," requirements that weren't satisfied here:

Reasonableness is to be assessed in light of the purpose of the forum, which here is to "communicate and interact with citizens," and to "encourage respectful and constructive dialogue" through the public's comments. Reasonableness in this context is thus necessarily a more demanding test than in forums that have a primary purpose that is less compatible with expressive activity, like [speech by attendees at a] football stadium …. In service of those purposes, NIH's off-topic restriction furthers the "permissible objective[s]," of creating comment threads dedicated to each post's topic and allowing the public to engage on that topic, instead of being distracted or overwhelmed by off-topic comments.

But NIH must "draw a reasonable line," informed by "objective, workable standards," between what is considered on-topic and what is considered off-topic. "Although there is no requirement of narrow tailoring," the government "must be able to articulate some sensible basis for distinguishing what may come in from what must stay out." This NIH has not done.

In the context of NIH's posts—which often feature research conducted using animal experiments or researchers who have conducted such experiments—to consider words related to animal testing categorically "off-topic" does not "ring[ ] of common-sense." For example, consider NIH's July 20, 2021 Instagram post, which featured a photo of the eye of a zebrafish. The caption read, in part: "This picture of an anesthetized adult zebrafish was taken with a powerful microscope that uses lasers to illuminate the fish." It is unreasonable to think that comments related to animal testing are off-topic for such a post. Yet a comment like "animal testing on zebrafish is cruel" would have been filtered out because "animal," "testing," and "cruel" are all blocked by NIH's keyword filters.

The government admits that animal testing comments would be on-topic for that post and instead argues that the off-topic rule is still reasonable because a reasonable policy may be both over- and underinclusive. That argument assumes the zebrafish post is an outlier. But the record indicates otherwise. A substantial portion of the NIH posts included in the stipulated record either directly depict animals or discuss research conducted on animals. To say that comments related to animal testing are categorically off-topic when a significant portion of NIH's posts are about research conducted on animals defies common sense.

Worse, the government fails to provide any definition of "off-topic" in its Comment Guidelines, to its social media moderators, or even in this litigation. See Oral Arg. Tr. 29:4–7 (NIH arguing that "off topic" is a "commonly understood" term but providing no explicit definition); id. at 29:20–21 (NIH stating that "[t]here's nothing in the comment guidelines that define[s] what off topic means"); id. at 54:22–55:25 (NIH stating its moderators use their "experience"). And without such guidance, in this context at least, it is far from clear where the line between off-topic and on-topic lies.

Take another recurring example from the record: An NIH post highlighting a study by a researcher who regularly conducts experiments on animals but did not conduct any such experiments in the particular study highlighted.

One could argue that a comment criticizing that researcher's general use of animal testing is on-topic, because the post introduced the researcher as a "topic" of the post. But one could also reasonably think that such a comment is off-topic because the specific study highlighted is the relevant "topic," and the study itself did not involve animal testing. Simply announcing a rule against "off-topic" comments does not provide "objective, workable standards" to guide either NIH's social media moderators or the public as to how to divine "what may come in from what must stay out." Though we have never required a speech restriction to demonstrate "perfect clarity," the problem with NIH's off-topic rule goes "beyond close calls on borderline or fanciful cases." Moreover, while NIH claimed in this litigation that there was an "alarming number of repetitive, off-topic" comments about animal testing, NIH provided no line (either to us or to its own social media moderators) demarcating what is an acceptable number of off-topic posts and what is too much.

"It is 'self-evident' that an indeterminate prohibition carries with it '[t]he opportunity for abuse, especially where [it] has received a virtually open-ended interpretation.'" It is perhaps no surprise then that NIH's moderators originally added terms like "PETA" and "#stopanimaltesting" to the keyword filters which were then, during this litigation, removed once NIH realized those terms "may have signaled a certain viewpoint." The district court forgave these keyword choices as "an overzealous attempt by a NIH social media manager to tamp down irrelevant posts." To us, however, these missteps are confirmation that NIH's policy does not "guide[ ]" its social media managers with any "objective, workable standards." That undermines the reasonableness of the NIH policy.

NIH's off-topic policy, as implemented by the keywords, is further unreasonable because it is inflexible and unresponsive to context. In American Library Association, for example, even though the pornography filters erroneously blocked some websites that did not show pornographic content, the Supreme Court held that the policy was reasonable in part because library patrons could easily disable the filtering software by asking a librarian to unblock the site either temporarily for their own use or permanently for use by others.

By contrast, NIH's moderation policy lacks comparable features. The keyword filters apply automatically to comments on all NIH posts. They do not account for the topic of any given post or the context in which a comment is made—for example, a long comment that is generally responsive to the post would be filtered out if it uses any one of the keywords. Further, NIH does not employ any manual review of comments to restore otherwise on-topic comments that have been removed, turn off its filters when it posts content that is likely to make certain keywords relevant, or even routinely review its keyword list to consider whether its keywords should be removed (at least absent a lawsuit). Users seemingly have little, if any, ability to ask NIH to restore their comments; indeed, they typically are not notified when their comments are filtered out. The permanent and context-insensitive nature of NIH's speech restriction reinforces its unreasonableness, especially absent record evidence that comments about animal testing materially disrupt NIH's ability to meet its objective of communicating with citizens about NIH's work.

Finally, NIH's off-topic restriction is further compromised by the fact that NIH chose to moderate its comment threads in a way that skews sharply against the appellants' viewpoint that the agency should stop funding animal testing by filtering terms such as "torture" and "cruel," not to mention terms previously included such as "PETA" and "#stopanimaltesting." The right to "praise or criticize governmental agents" lies at the heart of the First Amendment's protections, and censoring speech that contains words more likely to be used by animal rights advocates has the potential to distort public discourse over NIH's work. The government should tread carefully when enforcing any speech restriction to ensure it is not viewpoint discriminatory and does not inappropriately censor criticism or exposure of governmental actions.

For all of these reasons, we hold that NIH's off-topic restriction, as currently presented, is unreasonable under the First Amendment. We therefore do not separately address whether the specific keywords used to implement the off-topic rule are, by themselves, viewpoint discriminatory….

PETA was represented by Stephanie Krent, Ashley Ridgway, Katherine A. Fallow, Alexia Ramirez, and Jameel Jaffer.

The post D.C. Circuit Strikes Down Automated Filtering of Supposedly "Off-Topic" Comments on NIH Site appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: August 6, 1792

8/6/1792: Justice Thomas Johnson takes judicial oath.

Justice Thomas Johnson

Justice Thomas Johnson

The post Today in Supreme Court History: August 6, 1792 appeared first on Reason.com.

August 5, 2024

[Steven Calabresi] Biden-Harris on Supreme Court Term Limits

[An attack on the independence of the federal judiciary.]

President Biden launched an attack on the independence of the federal judiciary on July 29th when he endorsed the packing of the U.S. Supreme Court. He did this in an op-ed in the Washington Post and then in a partisan speech that same day commemorating the 60th anniversary of the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. His Vice President, Kamala Harris, endorsed Biden's comments and indicated that she would be more aggressive on this issue than Biden has been. Packing the Supreme Court is thus a key issue in the 2024 presidential and senatorial elections, as GOP Senate candidates running in red or purple states like Montana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan, Nevada, and Arizona should make clear.

Technically, Biden and Harris are probably calling for a statute that would unconstitutionally limit the voting rights of Supreme Court justices to 18-year terms in violation of Article III of the Constitution. I base this inference on my knowledge of the proceedings of President Biden's Supreme Court Reform Commission, since Biden's July 29th op-ed and speech provided no specifics. The Biden-Harris proposal of July 29th reflects the fact that a solid majority of voters oppose court packing, but voters like the idea of Supreme Court term limits by a large margin. Term limits on Supreme Court justices could be legally imposed by constitutional amendment, which would require a bipartisan consensus, and, if the term limit were long enough, it might be somewhat reconcilable with judicial independence. In reality, the Biden-Harris proposal is both a disguised court packing plan, which voters rightly oppose, and it is also unconstitutional and the greatest threat to judicial independence since President Franklin D. Roosevelt tried unsuccessfully, in 1937, to increase the size of the Supreme Court from 9 to 15 justices.

Biden tipped his hand that he is asking for a statute imposing an 18-year term limit on the voting rights of Supreme Court justices in cases or controversies before the Supreme Court because, in his July 29th proposal, he called for a constitutional amendment to overturn a recent Supreme Court case that he disagreed with, but he pointedly did not call for a constitutional amendment to enact an 18-year term limit on Supreme Court justices' voting rights on cases before the Supreme Court. Biden also did not specify whether such a package would apply retroactively to the nine current Supreme Court justices or prospectively, as some members of his Presidential Commission on Supreme Court reform have suggested it should. President Biden, and some members of his Commission, seem to think that the mere passage of a statute and not a constitutional amendment is all that is needed to eliminate the voting rights of Supreme Court justices once they have served for 18 years. I am not aware of any Republican member of Biden's Commission or of any right of center legal scholar or lawyer who currently thinks that what Biden-Harris are contemplating is constitutional.

How would the Biden-Harris plan work in practice if the Democrats win the 2024 election this November 5th? Imagine that sometime after noon on January 20, 2025, Senate Democrats, if they are still in the majority, eliminate the filibuster for a Supreme Court packing effort, disguised as an 18-year term limits bill on voting rights of Supreme Court justices on cases or controversies before the Supreme Court, which requires 60 votes to end debate. Then imagine that Kamala Harris has been elected president, that the Senate has ended up tied 50 to 50 as happened four years ago in the election of 2020, and that Kamala Harris's Vice President holds the tie breaking vote, enabling Supreme Court packing to pass in the Senate by a partisan vote of 51 to 50. Finally, imagine that Democrats win a slim majority in the House of Representatives. The Biden-Harris court packing statute, disguised as an unconstitutional 18-year statutory term limit on Supreme Court justices voting power would become a law awaiting judicial review as to its constitutionality.

All of this could easily happen, and with the retirement of Senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema there are probably no Democrats left in the Senate who would oppose the abolition of the filibuster if it stood in the way of enacting such a statute. Based on their voting records between 2021 and 2023, when the Senate was last evenly divided, and fresh off a successful 2024 reelection campaign, Montana Senator Jon Tester, Ohio Senator Sherrod Brown, Pennsylvania Senator Bob Casey, Wisconsin Senator Tammy Baldwin, and Nevada Senator Jacky Rosen would be highly likely to join the rest of their party. If red-state Senate Democrats do not intend to join the Biden-Harris court packing bandwagon, they should publicly and loudly denounce the Biden-Harris court packing plan right now, before the November 5th election, and commit to voting against it.

Although the details remain to be spelled out, the immediate effect of an unconstitutional retroactive court packing law, disguised as a term limits law, would be to remove as voting members of the Supreme Court, on cases before that Court, three out of the six of the moderate, libertarian, and conservative Republican-appointed current life-tenured Supreme Court Justices who have served for more than eighteen years: Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito. Strikingly, no progressive or Democratic-appointed Justices would be removed. Such a law would then allow President Harris and a Democratic Senate to appoint three new progressive justices—one for each of the removed justices who have served for longer than 18 years. The number of justices would also technically increase from 9 to 12, although the 3 term-limited Justices would no longer have a vote on cases before the Supreme Court. This combination is what makes the Biden-Harris proposal, if retroactive, a court packing plan and not a term limits plan.

To be sure, the new progressive justices, in turn, would be unconstitutionally term limited to 18 years. But this would be a long time far into the future—in 2042. Meanwhile, the law would immediately remake the voting membership of the Supreme Court from a 6 to 3 moderate, libertarian, and conservative Republican-appointed majority, into a Supreme Court with a 6 to 3 Progressive Democratic-appointed majority, and three Republican-appointed members without a vote on cases before the Supreme Court: Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito. President Harris's court packing bill, if it applied retroactively, would change the Supreme Court from a 6 to 3 majority of voting moderate, libertarian, and conservative Republican-appointed Justices to a 6 to 3 majority of voting progressive Democratic-appointed Justices through her new appointees. Thus, a retroactive court packing statute, disguised as an 18-year term limit on Supreme Court justices, would unconstitutionally give Democrats a 6 to 3 voting majority on the Supreme Court perhaps until 2042.

A prospective court packing law that simply added three new 18-year term limited justices, for each justice who has served more than 18 years, would lead to a 12-member Supreme Court that is tied 6 to 6. Either way, the statute Biden and Harris have in mind is a court packing law and not an 18-year term limits law. I am basing my discussion of what Biden and Harris may have in mind on conversations with key members of President Biden's Supreme Court Reform Commission, a number of whom are close personal friends. Either way, whether it is retroactive or not, the term limits statute the Biden Commission on Supreme Court Reform proposal favored, which never made its way into the public eye, is unconstitutional. Perhaps President Biden meant to put forward this proposal in his second term, which he will no longer serve due to his withdrawal as a candidate for President in 2024.

This proposed Biden-Harris "term limits" / court packing plan described above is the greatest threat to judicial independence since President Franklin D. Roosevelt tried unsuccessfully to pack the Supreme Court in 1937. His proposal would have increased the number of justices from 9 to 15—6 justices for each of the then-9 justices who were over the age of 70. The Court's membership has been fixed at 9 justices since 1869—a period of 155 years. Other than FDR's unsuccessful 1937 court packing plan, and some short-term court packing during the immense crisis of the Civil War, no Supreme Court packing law has ever passed in 235 years of American history. The size of the Supreme Court did increase from 6 justices at the founding, to 7 and then 9, before 1861, as the population and number of states in the union increased exponentially. None of those increases were motivated by a desire to pack the Supreme Court outright, as is explained in Joshua Braver, Court Packing: An American Tradition?, 61 Boston College Law Review 2747 (2020). While I think that what FDR tried to do in 1937 was also unconstitutional, I will confine my comments today to addressing the constitutionality of what I know to be the plan for statutory court-packing as term limits on justices' voting, which the Biden Commission on Supreme Court Reform considered.

The present nine life-tenured justices would be duty-bound to hold statutory term limits schemes, whether retroactive or prospective, unconstitutional. The term of office and powers, including the power of voting on cases before the Supreme Court, of life tenured Supreme Court can no more be altered by statute than can be the term of office or powers of the President, the Vice President, Senators, or Representatives, or of any state elected officials. Congress could not by statute take away the Vice President's tie breaking vote when the Senate is equally divided. Biden and Harris, of all people, should understand that, having served both as Vice Presidents and Senators.

The insurmountable constitutional and legal problem with President Biden's Supreme Court term limits statute in any form is that Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution says explicitly that:

"The judges, both of the supreme and inferior courts, shall hold their offices during good behaviour …." This clause, on its face, renders any term limits, retroactive or prospective, on the Supreme Court judges unconstitutional. Such term limits cannot be achieved by the subterfuge of eliminating voting rights on cases of Supreme Court justices but not the justices' title, for reasons implicit in U.S. Term Limits Inc. v. Thornton, 514 U.S. 779 (1995) (limit on eligibility to be on the ballot is a subterfuge for an unconstitutional term limit).

Since 1761, British law has defined "good behaviour" to mean life tenure absent conviction of a felony. The Framers of the U.S. Constitution clearly understood it to mean at least that too, with a felony on its own probably insufficient absent a special impeachment and conviction proceeding in addition. That is also how tenure during good behavior has been widely understood by Americans, including American Presidents, from 1789 until President Biden's speech on July 29, 2024.

The only clause in the Constitution that even comes close to empowering Congress to legislate as to the Supreme Court reads as follows in relevant part (emphasis added):

The Congress shall have Power … To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution … all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.

Congress thus does have the power to make "necessary and proper laws for carrying into execution" the judicial power of the life tenured justices and judges. Congressional power over the judiciary under this Clause has, however, been construed to be limited by the critical principle of judicial independence, which is the right way in which to construe it. See Plaut v. Spendthrift Farm Inc., 514 U.S. 211 (1995) (opinion of the court by Scalia, J). I think, as Plaut ruled, that the Necessary and Proper Clause does not allow the Congress to retroactively require courts to effectively reverse themselves on previously adjudicated cases, which is merely an implication of the principle of judicial independence. Much less does it allow Congress to effectively nullify Supreme Court Justices' life tenure by curtailing the justices' voting rights on cases before the Supreme Court after 18 years when the President and Congress are "displeased" with the Court's decisions.

Some too-clever-by-half law professors (to some extent including me, 22 years ago) have claimed that proposals of the type considered by the Biden Supreme Court Reform Commission are not really an attack on the Justices' life-tenure. They argue that from 1789 to 2024, Supreme Court justices have held two federal, judicial offices: the first deciding cases that come before the Supreme Court, and the second riding circuit or hearing cases on the lower federal courts. Congress first curtailed and then eliminated circuit riding in the Nineteenth Century at the request of the Supreme Court justices themselves when it created many lower federal court judgeships. But, even today, Supreme Court justices are also circuit justices who hear requests for stays from their home circuits. They can also decide federal court of appeals or district court cases in any circuit when they are designated to do so by a lower federal court chief judge.

Yet the abolition of circuit riding was constitutional for the same reason the Supreme Court upheld the abolition of 16 federal court of appeals judgeships created by the lame duck John Adams Administration and a lame duck Federalist Congress in February of 1801. See Stuart v. Laird, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 299 (1803). Congress can abolish a level of inferior court judgeships, the inferior judges of which have tenure during "good behaviour," and it can stop Supreme Court justices from hearing cases on inferior courts, but it cannot redefine "good behaviour" to constitute voting rights on the Supreme Court for only the first 18 years of a Supreme Court justice's service.

The law professor proponents of statutory term limits claim that Congress could retroactively redefine the office of Supreme Court judge to clarify that justices vote only on Supreme Court cases for the first eighteen years after their appointment as Supreme Court judges, and then for the rest of their lives they have tenure during good behavior as circuit court judges who still have the title of Supreme Court judge but not the power to vote on cases before the Supreme Court. But this position is in my now considered judgment a mistaken view. I have changed my mind on this in the last 22 years, as I will explain further below. Everyone has long understood that the primary responsibility of the "office" of Supreme Court Justice is to serve as the final arbiter who votes in cases or controversies properly before the Supreme Court.

Moreover, the office of "judge of the supreme court," unlike the office of circuit judge, which Congress created by statute in 1789, is one of the very few offices created by the Constitution, itself, and not by a federal statute. This is made clear by its mention in the Appointments Clause, which explicitly says that: "[The President] shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law."

Congress has no power by statute to alter this constitutionally created and tenured office or its powers, an office and powers that are currently held by nine life-tenured men and women. In this office, which the Constitution itself creates, those nine Justices have the duty (in Latin, officium, from which the English word "officer" is derived) to vote on all cases or controversies before the Supreme Court. Similarly, Congress cannot alter the terms of offices, or the powers of those who hold such offices, as the Members of the House of Representatives, the Members of the Senate, the President, the Vice President, presidential electors, the Chief Justice of the United States, and ambassadors and other public ministers and consuls. The Supreme Court has also correctly rejected efforts by State legislatures to impose term limits on members of Congress notwithstanding the state legislatures' express and residual authorities to regulate elections and ballot access under the Tenth Amendment. See U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton, 514 U.S. 779 (1995).

All offices of the United States other than the ones noted above (except for the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate) are created by Congress by statute and can be term limited by Congress; but that's not so for any "supreme or inferior" federal court judgeships. Congress can no more change the term of the "office" or the voting rights of Supreme Court justices or "Judges" by statute than it can do so as to the term of office or the powers of the President, the Vice President, Senators, or Representatives. Nor can the states change the term of office of any federal officials by, for example, effectively imposing term limits on their federal Senators and Representatives. See U.S. Term Limits.

The American people adopted the Twenty-Second Amendment to limit U.S. presidents to no more than two elected terms or a total of ten years in office. This was an exceptionally wise and bold move, which exempted from the two-term limit the then-serving President, Harry S. Truman. Just as it was necessary to pass a constitutional amendment to limit presidents to two terms prospectively, it is also necessary to pass a constitutional amendment to term limit or change the voting powers of Supreme Court justices, and a constitutional amendment would also be necessary to change the term of office or powers of the Vice President, or of Senators or of Representatives. No-one thought, in 1947, that Congress could by statute pass as "necessary and proper" a law that carried into execution the President's "four-year term of office" by adding the limit that he could serve for only two four-year terms. The Framers of the Constitution considered these sorts of ideas and rejected them out of hand, as the words of the Constitution show. Nor did anyone think that such a statute could have left Franklin D. Roosevelt with the title, but not the powers, of the presidency, when he began his third term as President in 1941, while some other individual also called the President somehow had all the powers that belonged to FDR under the Constitution.

The Biden-Harris plan is thus unconstitutional and should not be taken seriously by anyone. And it is also bad public policy for at least five reasons.

First, it would in practice be the end of judicial independence, which has been essential to the rule of law and the endurance of the American experiment. Instead, it would hopelessly politicize the Court, both immediately and in the long term. The new Court majority would owe their jobs to the current President and Congress far more directly than the does the current majority of Supreme Court justices. The next time Republicans win the presidency and simple majorities in both Houses of Congress, they would simply repack the Supreme Court themselves.

Such a move by Biden and Harris, with the certainty of a tit for tat by Republicans, is a great threat to our constitutional republic. What the Democrats do without bipartisan support in 2025, the Republicans will certainly do again without bipartisan support whenever they get a trifecta. It is no exaggeration to say that in short order this would end the 235-year American experiment with constitutional democracy.

A second policy problem, considered by Biden's Supreme Court Reform Commission, is that when that plan is fully implemented, it would provide that one of the nine seats on the Supreme Court would open every two years over an eighteen-year cycle. This would give every two-term president four seats to fill, which is almost always enough to tip the balance on the Supreme Court. As of 2024, we have had fifteen presidents who have served eight or almost eight years in office. They include George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, Ulysses S. Grant, Grover Cleveland, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama.

What would it be like to live in a country which has had fifteen major shifts in constitutional caselaw instead of, or possibly in addition to, the perhaps five or six major shifts in caselaw that our life tenured Supreme Court has produced? The Supreme Court would become much like the National Labor Relations Board, which is quickly dominated by labor unions during Democratic Administrations and by the Chamber of Commerce during Republican Administrations. So much for the rule of law and the Constitution. What is next? Abolishing the fifty states or the Senate by statute?

A third policy problem that bears noting is that the Biden-Harris term limit of 18 years would have cut short the tenure of many Justices long admired by Progressives, among others Thurgood Marshall, Louis Brandeis, Joseph Story, William J. Brennan, Jr., John Marshall Harlan the elder, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Hugo Black, John Marshall, and John Paul Stevens.

Do Biden-Harris, and Democratic Senate candidates in red states like Montana and Ohio, really want to cut short the judicial careers of all people like this? After all, many Supreme Court justices are said by progressives to "grow in office." That would happen to a much lesser degree with a statutory term limit of 18 years on the service of Supreme Court justices.

A fourth policy problem with the Biden-Harris plan is that twice in American history when one party controlled the presidency, the Congress, and the Supreme Court the results were catastrophic. In 1944, when New Deal Democrats controlled the presidency, Congress, and the Supreme Court, they abused their power in Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944). Six of the eight Democratic appointees on the Supreme Court voted to let President Franklin D. Roosevelt send 100,000 Japanese American citizens to concentration camps solely because of their race.

An earlier abuse of power occurred in the late 1790's when the Federalist Party controlled the presidency, the Congress, and all the federal courts. Between 1798 and 1801, Federalist Party justices and judges appointed by Federalist Party Presidents, George Washington and John Adams, used the Sedition Act of 1798 passed by a Federalist Party Congress to jail Democrats for, among other things, calling President Adams "pompous," "foolish," "silly," and a "bully." The courts jailed and fined citizens and even a congressman from Vermont, even though the speech in question was clearly constitutionally protected under the First Amendment.

The fifth and final public policy problem is that in arguing for an 18-year term limit for U.S. Supreme Court justices, President Biden gives great weight to the fact that other constitutional democracies have term limits or mandatory retirement ages on their "equivalents" to our Supreme Court justices. Biden misses, however, the fact that the United States differs greatly from all of those other much less free, much less wealthy, and much less populous constitutional democracies. From 1789 to the present, the United States has been "a shining city on a hill," which all of the other constitutional democracies formed since 1875 have strived imperfectly to emulate. Millions of Southern, Eastern, and Central Europeans; Arab and Sub-Saharan Africans; West, South, and East Asians; and Central and South Americans would all come to live in the United States, if they legally could do so, while virtually no Americans, including oppressed Black Americans, try to leave our country.

I suspect that judicial life tenure is one of the reasons why the United States is freer than any other constitutional democracy. I also suspect that the high level of certainty in U.S. law, especially Supreme Court caselaw, has reduced the risk factor in investment in the United States. This in turn explains why the United States has the highest GDP per capita of any of the G-20 nations, which are constitutional democracies.

Salman Rushdie could publish The Satanic Verses in the United States and be confident that he would not be prosecuted for doing so in 20 years. Sadly, this is not the case in Canada, Germany, France, Brazil, India, or many other constitutional democracies, in some of which, like India, I have been told by scholars that Rushdie's book is banned. Elon Musk can start SpaceX in the United States and be confident that it would not be nationalized with inadequate just compensation in twenty years. Sadly, this is not the case in many other constitutional democracies.

Our life tenured Supreme Court, and the certainty that it creates have played a central role in establishing the liberty and prosperity evidenced by our unequaled GDP per capita among the G-20 nations. I lay out the evidence for this claim in 700 pages in a two-volume recently published book series, The History and Growth of Judicial Review: The G-20 Common Law Countries and Israel (Oxford University Press 2021) and The History and Growth of Judicial Review: The G-20 Civil Law Countries (Oxford University Press 2021). The research I did for these two books caused me to rethink my earlier support, as a policy matter, for Supreme Court term limits of 18 years accomplished by constitutional amendment or statute. See Steven G. Calabresi & James Lindgren, Term Limits for the Supreme Court: Life Tenure Reconsidered, 29 Harv. J. of L. & Pub. Pol. 769 (2006), and a 2020 op-ed in The New York Times. I once in 2002 signed an op-ed with Professor Akhil Reed Amar endorsing statutory 18-year term limits, but I recanted that view in my 2006 law review article with Lindgren, writing that statutory term limits were unconstitutional and unwise.

The other constitutional democracies that have term limits or mandatory retirement ages on their Supreme Courts or Constitutional Courts—their equivalents to the U.S. Supreme Court when it comes to having the power of judicial review—all give much more power to those "courts" than the U.S. Constitution gives to the U.S. Supreme Court. All of these foreign "courts" have the power to issue advisory opinions; lack a strict standing doctrine, like the one set forth by the U.S. Supreme Court; or allow citizen/taxpayer standing, which is not allowed in the U.S. and which hugely broadens the range of issues which a Supreme Court or Constitutional Court can rule on. Several foreign Supreme or Constitutional Courts have the power to declare constitutional amendments unconstitutional. Several also allow their current justices or judges to select their successors without meaningful input from elected officials.

This medieval guild system of incumbent judges selecting their judicial successors resembles the medieval guild system of U.S. law schools where faculty members select their own successors, a job which faculties do not do very well. In contrast, U.S. Supreme Court justices are selected by democratically elected officials through presidential nomination and senatorial confirmation. This reduces the counter-majoritarian difficulty, which judicial review creates.

In short, the reason why so many foreign countries have term limits, or age limits, and the U.S. Supreme Court justices do not, is because the foreign equivalents to our Supreme Court justices are significantly less constrained in other ways. They are therefore more in need of additional constitutional restraint than is the U.S. Supreme Court because they are not really "courts" as Americans have always understood that word.

Court packing, or term limits, would sharply undermine the independence of our judiciary. It's unconstitutional, and it's bad policy. I hope that Senators of both parties speak out against it.

The post Biden-Harris on Supreme Court Term Limits appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: August 5, 1974

8/5/1974: Shortly after the Supreme Court decided United States v. Nixon, President Nixon released the "smoking gun" tape recorded in the Oval office.

President Richard Nixon

President Richard NixonThe post Today in Supreme Court History: August 5, 1974 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Monday Open Thread

[What's on your mind?]

The post Monday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

August 4, 2024

[Josh Blackman] Justice Gorsuch Explains What Collegiality Means

[Does it mean going to the opera together, or a willingness to be persuaded?]

It seems that Justice Gorsuch is going through the media circuit in advance of his book launch. Yesterday I wrote about this interview with the Wall Street Journal. Today, David French of the New York Times published a transcript of his NMG sit down. To go back to one of my hobby horses, when a publisher gives a book deal to a Justice, with a large advance, the publisher knowns that the media will gladly sit down for interviews in Supreme Court chambers. This is free press that cannot be purchased–well it can be purchased with a substantial advance. All the more reason to place a cap on royalties for Justices. I digress.

French and Gorsuch had an extended discussion of what was learned from the COVID cases. In truth, we need to reflect a lot more on that period than we have. So many of us (present company included) made some terrible decisions. Our faith in the power of government and self-professed "experts" was largely misplaced. And nothing that has happened since the pandemic has restored my faith. Chief Justice Roberts's "super-precedent" in South Bay has not aged well. I have to imagine that distrust was lurking in the background of Loper Bright.

I found the most enlightening exchange to turn on collegiality. I think that is a term that many people use to mean different things. It was well known that Justices Scalia and Ginsburg were dear friends, and often socialized together. They were collegial. But did RBG ever persuade Scalia to change his mind, at least on a big case? Probably not. Does that mean they were not collegial?

Of late, Justice Kagan has been pushing the latter conception of collegiality–that it entails having an open mind, and a willingness to be persuaded. I have to imagine this push is part of her effort to corral Justice Barrett's votes at every opportunity. If there is any common thread with Joan Biskupic's reporting, is that Justice Kagan flipped Justice Barrett in several cases. I've yet to see any indication that a conservative Justice has flipped a liberal member of the court to reach a conservative outcome. Flipping is not ambidextrous–it only works on the left.

I for one, reject the notion that collegiality entails a willingness to reconsider your views. It is always a judge's role to find the truth, and determine the best answer to a particular legal dispute by his or her best lights. And that process primarily entails weighing the arguments advanced by counsel, and deciding which side should prevail. To be sure, judges on a multi-member court will lobby one another for this position or that position. And to maintain relations, it is important to be willing to listen. But I do not think collegiality requires anything more than listening. Indeed, there are problems with this sort of ex-post lobbying that happens after the briefs are submitted and arguments conclude. Perhaps the parties have obvious rejoinders to some post-hoc position raised, but there is no chance to discuss it. The vote at conference reflects an assessment of the actual case, as it is presented. But when votes change after conference, invariably, it will be because of some newly-determined facet of the case that the parties did not have the chance to address. The Court could always order re-briefing and re-argument, but alas, the pattern has been to simply decide cases on grounds that would be entirely foreign to the lower courts. NetChoice and Moyle comes to mind.

David French poses this question to Justice Gorsuch, which he sort-of-answers, indirectly.

French: Justice Kagan gave some remarks to the Ninth Circuit recently where she talked about this issue of collegiality within the court. There's been some friendships, for example, most famously of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Justice Antonin Scalia. Also recently, Justice Sonia Sotomayor gave a speech in which she said some really kind things about Justice Clarence Thomas and the way that he interacts with court personnel.

But Justice Elena Kagan said something interesting. She said the collegiality that America should be looking for — and I'm paraphrasing — is not "Do we go to the opera together?" but "Are we open to each other?" Are we collegial enough to where we are open to each other? What is your temperature check on the collegiality of the court?

Gorsuch: Well, you're not going to drag me to an opera, David.

French: I wasn't expecting to.

Gorsuch: There's a lot in that question.

French: Yeah.

Gorsuch: I don't know whether you want me to talk first about the court.

French: Let's go first with the court and then with the culture.

Gorsuch: Sure. So with the court, I think it is important that we're friends and that we enjoy each other's company. We have a nice dining room upstairs. Lovely dining room, but it is the government, and we bring our own lunch. And oftentimes you'll see the chief justice with a brown bag and a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. OK. Those moments are important. They're human. But I also take the point that collegiality in a work environment means being able to work together well. And can I share just some numbers with you that I think tell the story on that?

Gorsuch goes on to explain that the Court decides many cases unanimously, and that he often votes for the "liberal" side of the case. And he says those unexpected coalitions are evidence of "collegiality."

Gorsuch: We decide the 60, 70 hardest cases in the country every year where lower courts have disagreed. That's the only point to get a case to the Supreme Court. We just want federal law — largely our job is to make sure it's uniform throughout the country, and if the circuit courts are in agreement, there's very little reason for us to take a case, unless it's of extraordinary importance.

So most of the work we do is when lower court judges disagree about the law. Magically, I think in this country there are only about 60 or 70 cases. You could argue a little bit more, a little bit less, but there aren't thousands of them. They're very few in number.

There are nine of us who've been appointed by five different presidents over the course of 30 years. We have very different views about how to approach questions of statutory interpretation, constitutional interpretation about political disagreements or interpretive methodological disagreements. Yet we're able to reach a unanimous verdict on the cases that come before us about 40 percent of the time, I think it might have been even higher this last term. I don't think that happens automatically.

I think that's the product of a lot of hard work. I think that's proof of collegiality. OK? That is what we do and we do well. Now people often say, "Well, what about the 6-3s?" Fair enough. Fair enough. But that's about a third of our docket. And it turns out they aren't always what you think they are. About half the 6-3s this last term are not the 6-3s you're thinking about.

Okay, Gorsuch does not actually answer the second part of Kagan's question. The fact that the Justices vote in unusual ways reflects the fact that all of the Justices are, to various extents, heterodox. They are not–contrary to what you might read–ideologues. Trust me, if we had an actual MAGA Court, things would look very different. But Gorsuch does not even hint that collegiality requires a willingness to be persuaded. It is the facts of a case, and the arguments advanced by counsel, that determine the unusual lineups.

I would like this same question posed to Justice Barrett. I think she might see things differently.

French also asked about Justice Kagan's ethics proposal. Gorsuch explains that the facts changed since Kagan's speech. Namely, President Biden wrote a pointless op-ed and Senator Schumer introduced a nuclear bill.

French: We're running out of time, so I do want to get to a couple of other questions. One, Justice Kagan also raised this interesting idea regarding ethics. And she talked about that the Supreme Court has a code of ethics that she appreciates, but she also talked about the possibility of enforcement through — and I'll read the quote here, one moment — "If the chief justice appointed some sort of committee of highly respected judges with a great deal of experience, with a reputation for fairness, you know, that seems like a good solution to me."

And a reason for that, the creation of sort of an outside judicial panel would, part of it would be to protect the court, to provide an outside voice that could not only adjudicate potentially valid claims but also debunk invalid accusations. And she made it clear she was speaking only for herself. What's your reaction to that concept?

Gorsuch: Well, David, since that talk, there's been some developments in the world, and this is now a subject that's being intensely discussed by the political branches, and I just don't think it would be very useful for me to comment on that at the moment.

In hindsight, would Kagan still have given her remarks, knowing what would come the following week? Or perhaps Kagan knew what was coming, and gave her remarks to shift the Overton Window? We are working with a crafty, plugged-in operator here, so be skeptical. How does that work for collegiality?

The post Justice Gorsuch Explains What Collegiality Means appeared first on Reason.com.

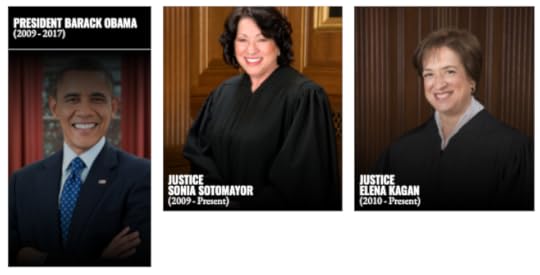

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: August 4, 1961

8/4/1961: President Barack Obama's birthday. He would appoint two Justices to the Supreme Court: Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

President Obama's appointees to the Supreme Court

President Obama's appointees to the Supreme CourtThe post Today in Supreme Court History: August 4, 1961 appeared first on Reason.com.

August 3, 2024

[Josh Blackman] Some Highlights From Justice Gorsuch's WSJ Interview

[Justice Gorsuch likes the new oral argument format and he writes his own opinions.]

Justice Gorsuch gave a wide-ranging interview with Kyle Peterson in the Wall Street Journal. The focus is his new book, which will be released on Tuesday. There are also some insights into how the Court functions post-COVID, and how his chambers operate.

First, Gorsuch strongly intimates that the Dobbs leak did not come from his chambers. I doubt any NMG clerks lawyered up, or refused to turn over their devices:

Did the Covid pandemic and the 2022 leak of the Dobbs abortion ruling change how the high court operates? Not much, apparently. "Unsurprisingly, the court has taken more security precautions with respect to its internal drafts," Justice Gorsuch says. He declines to detail what he told his clerks about the leak. "I can tell you," he says, in a low steely voice, "that it was very important to me that anybody who works for me was totally cooperative with the investigation. And they were."

Second, Gorsuch seems to appreciate the interminable round-robin format:

Oral arguments, influenced by pandemic teleconferences, have become "a little more leisurely." Lawyers now get two minutes to speak and settle in before the interrogating begins, which Justice Gorsuch says he loves: "They're all overcaffeinated and underslept, and they have a point they want to make." At the end, each justice is given a turn for final queries. "You don't have to elbow your way in," he says. "You never leave oral argument thinking, gosh, there's a question I wanted to ask."

I am not a fan. Then again, I'm not the one trying to ask questions.

Third, Gorsuch does not like his own writing:

Then comes the work of drafting rulings, where Justice Gorsuch says his colleagues shine. "I think we have an unusually large number of very gifted writers on the court right now," he says. "I'm not patting myself on the back. I put myself kind of in the middle of the pack, frankly." Asked if he has a favorite of his opinions, he answers without pausing to think: "Nope. I hate 'em all. Do you like reading your old writing?" Sometimes the job requires it. "Inevitably I think, ah, I wish I'd said this differently, ah, I didn't explore that enough."

I agree, and would put Gorsuch around the middle of the Court with writing prowess. My current top three are Roberts, Kagan, and Barrett. But Gorsuch writes in his own distinct tone, which works for him. On that point…

Fourth, Gorsuch states that he writes his own opinions. This is not surprising, since his tone is so distinctive, term-after-term:

What is his drafting process? "I like to have a law clerk do something," Justice Gorsuch says, even if he ultimately follows the practice of his old boss, Justice Byron White: "He'd say, write me something. And he'd read it. And then he'd throw it away. And then he'd write his own thing." This isn't to say the clerks are wasting time: "It's informative to see how another mind might approach the problem."

But then Justice Gorsuch sits down to write a complete draft himself. "It's a pretty intense, lock-yourself-in-a-room-with-the-materials process," he says. "At the end of the end of the end of the day," he says, repeating himself for emphasis, "I'm the one who took the oath, right? And I have to satisfy myself, that I've gone down every rabbit hole, and I understand the case thoroughly, and I'm doing my very best job to get it right."

I appreciate that Justice Gorsuch is now writing books at a regular clip. It is unfortunate that Gorsuch's royalties pale in comparison to his colleagues'. But that shouldn't matter. Gorsuch is writing about important legal topics, in much the same way that Justices Scalia and Breyer did. Gorsuch is trying to affect the long-term legal conversation. The other Justices are trying to… well, write about themselves.

For what it's worth, Gorsuch seems to identify as a libertarian-but-not-a-nut:

Whatever the cause, he worries that the U.S., with its accumulated statutory commands and regulatory crimes, is on the far side of what one might call the legal Laffer curve. "Too little law poses problems," he says. "I love my libertarian friends, but I am not with them on anarchy, OK? Law is essential." And yet: "Too much law actually winds up making people fear law rather than respect law, fear their institutions rather than love their institutions."

I can relate.

The post Some Highlights From Justice Gorsuch's WSJ Interview appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers