Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 2584

March 26, 2012

Prof. Eugene Kontorovich (Northwestern)

I'm delighted to report that Prof. Eugene Kontorovich of Northwestern Law School will be guest-blogging this week about the Alien Tort Statute. Prof. Kontorovich has written extensively on questions related to international and transnational law questions, and I much look forward to his posts.

(Note that due to a glitch on my side, this post didn't go up until later than I intended, so I've backtimed it to a few minutes before Prof. Kontorovich's post.)

March 25, 2012

Upholding the Mandate But Limiting Federal Power: A Response to Randy Barnett

My co-blogger Randy Barnett offered an interesting response to my post below on taking a vow of consistency in arguments about the mandate. In my post, I suggested that those who have argued that upholding the mandate would necessarily mean that the federal government has no limits should have to stick with that assessment if the mandate is upheld. If a majority upholds the mandate, those who have argued that upholding the mandate necessarily means there are no limits on federal power should not be able to switch positions ex post. In the comments, Randy responded:

Orin, realistically, does this not depend on the contours of the opinion upholding the mandate? For example, the majority opinion in Raich was based on the fact that the cultivation of marijuana was "economic" according to a 1966 Webster's dictionary defining "economic" as "the production, distribution and consumption of commodities." (I am paraphrasing, I did not look it up.) This was in sharp contrast with the government's sweeping rationale that anything that substitutes for a market good is "economic." No one, well at least not me, anticipated the Webster's dictionary definition, which greatly limited the scope of the Raich decision. Think about the 5 limiting "considerations" in Comstock. Are not future litigators entitled to utilize these factors in the future? (Notice, however, that the government and most mandate defenders do not take them very seriously when they claim that Chief Justice Roberts MUST uphold the mandate because he joined the opinion in Comstock.) What if the hypothetical opinion says that, because health care is genuinely unique — one of kind — mandates are *only* usable with health insurance? I am not saying they will write such an ad hoc opinion. Indeed, I fear they would not. And the government does not actually assert this limited a rationale. But supposing the opinion was written that way. Would a defender of enumerated powers need to ignore these limitations? Don't we have to wait and see?

I think Randy is clearly right in this paragraph. On one hand, a hypothetical opinion upholding the mandate could be written very broadly to eliminate future Commerce Clause challenges. On the other hand, such an opinion could be written very narrowly to permit and even encourage lots of future Commerce Clause challenges. So far we seem to agree. The problem, though, is that Randy's position above seems inconsistent with the argument mandate opponents have been making that if the mandate is upheld, it will mean the end of limits on federal power. As Randy shows in the paragraph quoted above, that's not the case: There certainly are ways to limit federal power and yet uphold the mandate.

I don't mean to dismiss the basic rhetorical moves of cause lawyering. We all know how it works: To make your case, argue that adverse precedents are very narrow while claiming that the sky will fall if the next case goes that same way. If you lose the next case, shift positions and claim the sky didn't fall, and that actually the decision in that case is not only very narrow but actually helps your position. (And if you win the next case, call it a pathbreaking case that redefines the entire field.) I think we all understand those moves, and the reasons for them. My point was just to suggest that if we insist on consistency between ex post and ex ante assessments of the significance of different decisions, we're likely to get a more accurate set of claims ex ante.

On a mostly-unrelated note, Randy asks at the end of his comment if the fact that the Supreme Court has agreed to hear the case and scheduled 6 hours of argument has changed my understanding of what "constitutionality" is (quotes in the original). I'm not sure I understand the question. But the Court had to take the case when there was a circuit split; it's a no-brainer grant. I think the 6 hours of argument shows that the Justices are intensely interested in the case and see it as very important. I give Randy a ton of credit for that surprising turn of events. His ideas really caught on in the political arena, which gave them legs in the judicial arena, and that changed the terms of the debate in a way that very likely led to the circuit split and therefore Supreme Court review. So kudos to Randy for that; it's a truly remarkable achievement. At the same time, I'm not sure what that elevated level of interest at the Supreme Court is supposed to suggest about the meaning of "constitutionality."

Guns, Broccoli and the Individual Mandate – Thoughts on the Eve of Argument

Is Department of Health and Human Services v. Florida a replay of United States v. Lopez? I suggested as much in an October 2010 post, in which I wrote:

n both cases, the issue is whether the Supreme Court will adopt limitations on the scope of government power that are greatly desired by libertarians and supported from an originalist perspective, but that Supreme Court doctrine hasn't shown any particular sign of adopting as a a matter of constitutional law. In both cases, the commentary in favor of the limitation seems aimed at fostering a sense of the legitimacy of those limitations with the hope that this will make it more likely for the Supreme Court to adopt them. In both cases, most informed observers were skeptical (if not incredulous) at the idea that the Supreme Court would take that step– only a handful of people saw the invalidation of the Gun Free School Zones Act as a realistic possibility; most saw it as extremely unlikely. In both cases, many commenters are extremely passionate about what they believe the correct constitutional answer must be — with commenters seemingly lining up in the same way on the two issues. And in both cases, most informed commentators would expect the Supreme Court to side affirm federal power.

There are differences, of course. The debate over the Commerce Clause pre-Lopez was more for law geeks than the public: It concerned the likelihood the Court would affirm the limitations of the federal commerce power for the first time in over fifty years in a low-profile case few had heard of, let alone cared about, and it lacked the broad political movement that exists over the individual mandate. Yet then, as now, the litigation occurred at a time when limited government political arguments were on the rise and now, unlike before, serious academics and court watchers believe that, as a predictive matter, the constitutionality of the individual mandate is an "open question." Nonetheless, I can't avoid the sense of deja vu — but maybe that's wishful thinking.

Since then, the debate over the constitutionality of the individual mandate has continued to follow the script. Prevailing elite opinion is dismissive of the arguments against the mandate, just as it was dismissive of the challenge to the GFSZA. Yet then, as now, defenders of the federal law have a difficult time reconciling their arguments with meaningful limits on federal power. Asked to identify something beyond the scope of the federal commerce power in Lopez, the Solicitor General came up empty. Asked to identify how the Supreme Court could uphold federal power to compel participation in commerce as a regulation in commerce, without green-lighting a near infinite power to command private activity the SG's office has also had a difficult time identifying the class of activities subject to regulation. This is one reason the SG's office has shifted its emphasis from "commerce" to what is "necessary and proper" and remains concerned about the "broccoli question."

Whereas some academics and commentators protest the mandate presents an easy case, those who actually have to argue the case in court recognize the need to reaffirm limits on federal power, even as they approve of the individual mandate. The difficulty in maintaining this position is one reason I have become more skeptical of the mandate's constitutionality over time. (My initial posts expressing skepticism of the anti-mandate arguments are here and here.) Harvard's Charles Fried may be comfortable proclaiming that Congress has the power to command all Americans to purchase broccoli or any other good or service, but he also felt Congress had the power to regulate the possession of guns in or near schools. Indeed, as the University of Pennsylvania's Ted Ruger recently recounted, Fried did not even teach the commerce clause prior to Lopez, as he did not believe the clause was relevant anymore. Many of those defending the mandate today felt much the same way, and have sought to minimize the importance of Lopez (and Morrison) ever since. Yet the Fifth Circuit then, and the Eleventh Circuit now, took the admonition that ours is a government of limited and enumerated powers more seriously, and invalidated an unprecedented assertion of federal power as a step too far. Then, a majority of the Supreme Court followed suit. Will they now?

As I noted two years ago, the statutory provisions at issue in HHS v. Florida are far more consequential provision than was at issue in Lopez. Few Americans had heard of the GFSZA, and even fewer had an opinion as to its constitutionality. Does this mean the challenges will fail? It is much easier for a court to invalidate a small piece of symbolic legislation than a major social reform. And yet, the Court has, at times, been willing to cut wide swaths through the federal code or confront the political branches. Dozens of statutory provisions were invalidated byINS v. Chadha, and the Court's aggressive review of the poltiical branches' wartime policy decisions in Boumediene were unprecedented, so it's not as if the Court has not flexed its muscles in the recent past.

The GFSZA may have been obscure, but that also meant it was not unpopular. If, as many believe, the Court is somewhat responsive to political pressures and popular sentiment, this could influence how the Court evaluates arguments that Congress has gone too far. Polls continue to show widespread opposition to the mandate and widespread skepticism about its constitutionality. Indeed, it's not very often that a majority of states unite against a federal statute, particularly when preemption, sovereign immunity, or other state prerogatives are not at stake. Thus a decision to strike down the mandate may offend academics and other legal elites, but it would not swim against the prevailing political tide or pick a fight with the political branches, as the Court did in Boumediene.

If pressed to make a prediction, it's always safer to assume the federal government will prevail before the High Court. It remains relatively rare for the Supreme Court to strike down a federal law. Yet the Court has confounded such expectations before — and there's a non-trivial chance it could do so again. Here's hoping.

The ACA and Mandatory Contraception Coverage

I wonder if folks at HHS were in contact with folks at Justice before they decided to announced a few weeks back that health insurers must cover contraceptives. While this requirement isn't directly pertinent to the constitutionality of the ACA, it weakens the government's defense in two extra-legal respects.

First, the laws' defenders want to focus on the issue of how the individual mandate alleviates the problem of the uninsured facing unexpected and catastrophic medical costs, which they then impose on the public to the tune of tens of billions of dollars.* But the headlines have been dominated by the issue of health insurers being required to pay for the very expected and relatively minimal (as low as $9 a month for birth control pills) cost of non-OTC contraceptives. This very much makes it seem like the ACA is as much about expanding federal power for the benefit of liberal constituencies as about the need for coordination in the interstate market for medical services to avoid problems related to the uninsured.

Second, while liberals don't typically associate federalism with the protection of liberty, conservatives do, and it's the conservative Justices whose votes the government needs. One of the "swing" Justices, Anthony Kennedy, waxed eloquent on the importance of federalism to individual rights just last term. Meanwhile, every one of the five conservatives on the Court is a Catholic. So pretty much the last thing you'd want if you were an Obama Administration lawyer defending the ACA is for HHS to announce just before oral arguments that henceforth under the ACA Catholic organizations, over the strong objections of the Church, will be compelled by the federal government to violate what they see as their Catholic religious obligations and provide contraception coverage to their employees. While the Flukes of the world see this as a victory for women's rights, I suspect that Kennedy and Roberts see it as a federal infringement on religious liberty [and not just any religious liberty, but their co-religionists' religious liberty!], with more to come if the ACA is upheld.

I don't know what the odds are that the Supreme Court will rule in favor of any of the plaintiffs' challenges, but I'm pretty confident that the odds in favor are higher than they would have been if HHS had kept its bureaucratic mouth shut about the contraception mandate for several more months.

*Just after I posted this, I ran across a great example, this statement by former acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal:

The challengers to the reform say that never before has the government forced people to buy a product. We're not forcing you to buy a product. Health care is something all Americans consume, and you don't know when you're going to consume it. You could get struck by a bus, you could have a heart attack and the like. And if you don't have health insurance, then you show up at the emergency room. The doctors are under orders to treat you — as any Western, any civilized society would do. And who pays for that? Well, ordinary Americans pay for that. They're the ones who have to pick up the tab for those who don't have insurance. We are not regulating what people buy, we're regulating how people finance it.

Notice how little the contraception mandate fits with this argument.

My New York Times Room for Debate Forum Piece on the Individual Mandate Case

The New York Times Room for Debate Forum has recently posted a set of short op eds by experts on both sides of the upcoming health care cases. My own contribution to the Forum is here. Here's an excerpt:

The individual health insurance mandate case raises momentous issues about the limits of federal power. As James Madison put it, the Constitution does not give the federal government "an indefinite supremacy over all persons and things." If the court upholds the mandate, that principle will be undermined.

The commerce clause gives Congress authority to regulate interstate commerce. Failure to purchase health insurance is not commerce, interstate or otherwise. Since the 1930s, Supreme Court decisions have interpreted the clause broadly. But every previous case expanding the commerce power involved some sort of "economic activity," such as operating a business or consuming.

If Congress could use the clause to regulate failure to purchase insurance merely because that choice has economic effects, there would be no structural limits to its power.

To my mind, the most interesting piece in the Forum is Vanderbilt lawprof James Blumstein's commentary on the unduly neglected Medicaid conditional funding case. This important issue deserves more attention than it has gotten so far.

The CIA's Enigmatic 'Roger'

Greg Miller has a fascinating front-page story in the Washington Post today (appears to be behind a free registration wall) profiling Roger, the mysterious head of the Counterterrorism Center at the CIA, a key figure in the pursuit of Bin Laden, and a principal architect of the drones program. Here's the money quote, borrowing from Lawfare:

Roger, which is the first name of his cover identity, may be the most consequential but least visible national security official in Washington — the principal architect of the CIA's drone campaign and the leader of the hunt for Osama bin Laden. In many ways, he has also been the driving force of the Obama administration's embrace of targeted killing as a centerpiece of its counterterrorism efforts.

Colleagues describe Roger as a collection of contradictions. A chain-smoker who spends countless hours on a treadmill. Notoriously surly yet able to win over enough support from subordinates and bosses to hold on to his job. He presides over a campaign that has killed thousands of Islamist militants and angered millions of Muslims, but he is himself a convert to Islam.

His defenders don't even try to make him sound likable. Instead, they emphasize his operational talents, encyclopedic understanding of the enemy and tireless work ethic.

"Irascible is the nicest way I would describe him," said a former high-ranking CIA official who supervised the counterterrorism chief. "But his range of experience and relationships have made him about as close to indispensable as you could think."

Miller's profile of 'Roger' is utterly compelling reading – I think once you start, you'll want to read the whole thing.

Shortcomings of the "Everyone Uses Health Care" Rationale for the Individual Mandate

The biggest weakness in the case for the constitutionality of the individual health insurance mandate is that it collapses into a rationale for virtually unlimited federal power. To deal with this problem, defenders of the mandate have put forward a variety of arguments claiming that health care is a special case.

The most popular one, recently restated by Walter Dellinger and Linda Greenhouse, is that health care is a special case because everyone or almost everyone uses it at some point in their lives. However, there is a serious flaw in this argument that mandate defenders have yet to find a way around. I have pointed it out several times over the last two years, including here:

The fact that most people eventually use health care does not differentiate health insurance from almost any other market of any significance. If you define the relevant "market" broadly enough, you can characterize any decision not to purchase a good or service exactly the same way. Notice that the government does not argue that everyone will inevitably use health insurance. Instead, they define the market as "health care." The same bait and switch tactic works for virtually any other mandate Congress might care to impose.

Consider the famous example of the broccoli mandate raised by Judge Roger Vinson in the Florida case. Not everyone eats broccoli. But everyone inevitably participates in the market for "food." Therefore, a mandate requiring everyone to purchase and eat broccoli would be permissible under the federal government's argument. The same goes for a mandate requiring everyone to purchase General Motors cars in order to help the auto industry. There are many people who don't participate in the market for cars. But just about everyone participates in the market for "transportation." We all need to get from place to place somehow. How about a mandate requiring all Americans to see the new Harry Potter movie? After all, just about everyone participates in some way in the market for "entertainment."

Interestingly, Greenhouse unintentionally illustrates this point herself. As she puts it:

The uninsured don't exist apart from commerce. To the contrary, their medical care results in some $43 billion of uncovered health care costs annually and, through cost-shifting, adds $1,000 a year to the average cost of a family insurance policy. People who don't want to buy broccoli or a new car can eat brussels sprouts or take the bus, but those without health insurance are in commerce whether they like it or not.

Brussels sprouts and buses are indeed alternatives to broccoli and cars. But Brussels sprouts are still part of the food market, and buses part of the market for transportation, in the same way as health insurance and other forms of health care provision are both part of the health care market. Thus, people "who don't want to buy broccoli or a new car" are still "in commerce" just like people who don't want to buy health insurance.

You can use similar reasoning to justify virtually any other mandate. Every good that we might be required to purchase or use is part of some broader market that all or most of us will not avoid. How about a mandate requiring people to read and study Volokh Conspiracy blog posts? After all, everyone at least to some degree uses the market for "information." And if you don't get information from the VC, you are still likely to get it from other (surely inferior) sources.

As Jonathan Adler points out, it is not in fact true that everyone uses the health care market. A few people do manage to avoid it. By contrast, the market for food really is literally impossible to avoid for anyone who wants to remain alive for more than a short time. Even if you grow all your own food without using any tools purchased from others, you would still be engaging "economic activity" as the Supreme Court defines that term. Far from distinguishing this case from the broccoli mandate, the "everyone uses health care" argument actually provides stronger support for food purchase mandates than for the health insurance mandate.

Mandate defenders have also advanced several other rationales for why this is a special case. I give a detailed critique of them in this article, and in the amicus brief I wrote on behalf of the Washington Legal Foundation and a group of constitutional law scholars (pp. 22-28). These rationales all suffer from much the same weaknesses as the "everyone uses health care" argument: their reasoning can justify virtually any other mandate, including the broccoli mandate, the car purchase mandate, and others.

So far, all the king's horses and all the president's men have yet to figure out a way to make this mandate special again. Indeed, it's noteworthy that the seriously flawed "everyone uses health care" argument remains the most popular of the different rationales for why the mandate is a special case. If the many outstanding lawyers and legal scholars on the pro-mandate side have not come up with anything better after two years of effort, that may indicate that no better argument is possible.

None of this will matter if the Court is willing to follow the lead of the D.C. Circuit, which upheld the mandate despite acknowledging that there are no limits to the federal government's logic. But, like David Bernstein, I highly doubt that a majority of the Justices are going to endorse the notion that congressional power is essentially unlimited.

UPDATE: For some reason, this post was initially time-stamped a day earlier than it should have been. I have now fixed this problem.

An Important Pledge of Consistency For Both Sides of the Individual Mandate Debate

Many opponents of the individual mandate have argued that if the individual mandate is upheld, there will be no limits whatsoever on federal power. Many proponents of the individual mandate have responded that there are several significant limits on federal power even if the mandate is upheld.

I propose that those who have voiced either position must now take a pledge of consistency. Here's how it will work. If you have argued that upholding the mandate would means that there are no limits on federal power, you should pledge now that if the mandate is upheld, you will never again argue that there are any limits on federal power. On the other hand, if you have argued that there are several significant limits on federal power that are entirely consistent with upholding the mandate, you should pledge now that if the mandate is upheld, you will never question or argue against any of those limits on federal power.

Deal?

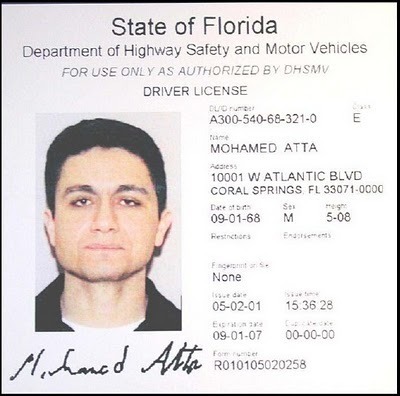

REAL ID — Back from the dead

I testified a few days ago at a House Judiciary subcommittee hearing on REAL ID implementation. I expected to have harsh things to say about the way REAL ID has been treated by the National Governors Association and the Obama administration. And there was certainly plenty to criticize. But what surprised me after a few years away from the issue was not how badly the secure ID problem had been neglected. It was how much progress has been made, almost reluctantly, by all parties. Much more secure identification is now within reach, though politics may still delay the final steps.

Here's some of what I told the subcommittee:

Unfortunately, not everyone agrees with the need for better drivers' license security. Opposition to REAL ID unites the nations' governors and the ACLU. As a candidate, President Obama campaigned against REAL ID. And as a governor, Secretary Napolitano did the same. So it was no surprise that the Obama administration supported repeal of REAL ID and adoption of a softer approach, called PASS ID. Expecting PASS ID to be adopted, the administration soft-pedaled the states' obligations under REAL ID.

But PASS ID did not pass, and REAL ID is still the law. Unfortunately, however, it's not being treated like a real law. In 2009, the Secretary of Homeland Security permanently stayed the deadline for states to come into material compliance, on the grounds that the Department was pursuing PASS ID. By March 2011, with the deadline for full compliance with REAL ID just two months away, that reasoning wouldn't work anymore; everyone recognized that PASS ID was dead. But the Secretary nonetheless postponed the deadline for full compliance to January 2013 without taking comments. The remarkable justification for the delay was that the administration had encouraged the states to hope that the law would change, so they didn't take steps to comply with the law as it stands:

…

I only wish I could get an extension on my tax return by saying I was hoping the law would change before the returns were due but that I'm now ready to "refocus on achieving compliance" with the requirements of the tax code.

In fact, apart from hoping that the states will refocus, the Department does not seem to be doing much to encourage them to meet the new deadline. As far as I can see, it hasn't audited state compliance; it hasn't processed the submissions of states that want to certify their compliance with REAL ID; and it hasn't pressed the states that are lagging far behind to step up their efforts.

…

[D]espite all the public outcry and political posturing, most motor vehicle departments are making good progress toward the goals set out in the REAL ID act. Janice Kephart of the Center for Immigration Studies has done invaluable work in surveying the states' progress toward achieving compliance with the standards set by REAL ID. Her most recent study estimates that nine states are on track to achieve full compliance with all REAL ID requirements by January 2013, and that another 27 will have achieved material compliance with the act by then. That means that the great majority of states can meet the deadline, at least for material compliance, if they simply keep on doing what they have been doing.

In saying that I do not mean to overlook the distinction between material compliance and full compliance. The principal difference is that states can achieve material compliance without having in place an electronic verification system for birth certificates. To achieve full compliance, they must check birth certificates with the issuing jurisdiction.

Now, as you might guess from my early remarks, I think that checking birth certificates is crucial to achieving a more secure license system. Birth certificates are much easier to forge and much harder to check than licenses, so it's no wonder that everyone from aspiring terrorists to cop-killing car thieves views a forged birth certificate as the key to building a fake identity.

And so, having an electronic system for checking birth certificates is crucial. It too should be in place as soon as possible.

…

Once again, there is good news on this front in the Kephart report, which says that by February of this year, 37 states had already entered their birth records into a system that allows other agencies to conduct verification online. This system, called Electronic Verification of Vital Events (or EVVE), is administered by the National Association for Public Health Statistics and Information Systems (or NAPHSIS). The network is still growing; NAPHSIS tells me that they've added another state since February; EVVE now covers 38 states. And the system isn't just theoretically available. It's actually being used on a daily basis by several US government agencies, such as the State Department's passport fraud investigators, the Office of Personnel Management, and the Social Security Administration.

The really good news, then, is that there are no technical barriers to nearly immediate implementation of electronic birth certificate checks. Any state that can achieve material compliance by 2013 can also achieve the most important element of full compliance by that date; it just has to hook up its DMV to EVVE. In short, nearly 40 jurisdictions are on track to do what the 9/11 Commission recently urged them to do: implement drivers' license security without delay.

The rest of my testimony is here.

The hearing itself was remarkable in several respects. Considering that there were three very different current or former Judiciary committee chairman in the hearing room (Sensenbrenner, Conyers, and Smith), there was much less heat than I expected.

Chairman Sensenbrenner, author of REAL ID, seemed pleased with the progress to date and disinclined to beat up the Administration. The Administration's witness (my successor at DHS Policy, David Heyman) said there were no plans to extend the January 2013 deadline for full compliance. The governors' witness was less hostile to REAL ID than in the past. The privacy groups were not much in evidence, and their arguments about the dangers of a giant database were undercut by the fact that four of the five data-sharing networks needed to implement REAL ID are already in operation, with George Orwell nowhere in sight.

There's a lesson here for government officials, especially those of us who are little impatient: Despite enormous friction and resistance, things that ought to get done in Washington do get done, eventually.

We aren't quite done with the fight to implement REAL ID, but if this were World War II, we'd be somewhere between D-Day and the Battle of the Bulge.

False Arguments in Favor of the Mandate

There are serious arguments in support of the constitutionality of the individual mandate (just as there are serious arguments against it). There are also quite a few bad arguments, and quite a few that rest on patently false premises. A common example of the latter is that the mandate does not require anyone to engage in commercial activity because all Americans will, in one way or another, eventually engage in health care markets. This is not true.

Here's an example. Walter Dellinger, in today's Washington Post, asserts: "The mandate does not force people into commerce who would otherwise remain outside it." This is false, as Dellinger's essay effectively acknowledges when it goes on to note that health care is "an activity in which virtually everyone will engage." This latter statement may be true. "Virtually everyone" may acquire health care — but "virtually everyone" is not "everyone." Most people may purchase health care at some point in their lives, but some will not. Some people will refuse to purchase health care for religious reasons. Some will not purchase health care because they are lucky enough not to need such care before a sudden death. Still others may decide not to purchase health care because they have chosen to remove themselves from commerce — consider a survivalist or other person who decides to live in a shack, growing their own food, and not engaging in commerce with others. All but the former are forced to enter into commerce who "would otherwise remain outside it." Indeed, under Cruzan, there is a fundamental right to refuse even life-saving health care. Therefore, the government cannot assume that each and every person will, at some point, use (let alone purchase) health care, as every American has the right to decide otherwise. These facts clarify the nature of the legal case for the mandate. Specifically, that some Americans could otherwise refrain from entering health care markets means that, in order to sustain the mandate the Court must conclude that in order to regulate commerce in which most Americans engage, the federal government has the power to force all Americans to engage in it.

Dellinger goes on to say that ""people who go without insurance often shift the costs of their health care to other patients and taxpayers. That situation is different from what happens with any other type of purchase." This latter claim isn't true either. Those who fail to acquire adequate levels of disaster insurance "often shift the costs" of disaster assistance on to others, as the federal and state governments regularly provide assistance to disaster victims above and beyond what their insurance provides. And yet the federal government does not mandate the purchase of flood or other disaster insurance.

That there is some number of people, however small, who would otherwise not engage in health care markets and that there are other contexts in which the under-insured shift costs on to others do not establish that the mandate is unconstitutional. But the persistence of arguments that rest on false premises is further evidence that the individual mandate case is not as easy as some like to suggest. After all, if this were such an easy case, advocates would not need to stretch the facts or make false claims to make their case.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers