Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 230

November 8, 2024

[Josh Blackman] The Supreme Court After The 2024 Election

What a difference a day can make.

On Tuesday morning, I woke up with some apprehension. No, not about the presidency, but about the judiciary. I was fearful that if Harris had prevailed, with majorities in both houses, the Supreme Court as we knew it would be gone. Through so-called judicial "reform," the long-standing nine-member Court would either be expanded, or tiered through term limits. Who on the left would oppose it? While the former approach is clearly within Congress's powers, the latter approach would be unconstitutional. Such a law would create a clash with the Court. And your guess is as good as mine about what would happen. Look how quickly the Mexican Supreme Court folded. There would also likely be expansion of lower court judges. When Steve Calabresi proposed this idea during the early Trump Administration, I vigorously opposed it. Thankfully, this idea never came to pass. But had Harris tried this approach, who on the left would oppose it? All we would hear would be noise about the Fifth Circuit, buttressed by a never-ending series of tweets, substacks, and podcasts. At that point, familiar debates about originalism and vacatur would become quite pointless. Much of my work in the field of constitutional law would amount to little. I do like teaching Property!

Tuesday was a very long day. I deliberately did not watch any cable news until about 8:00 ET when polls started to close on the east coast. With my many monitors, I was simultaneously watching CNN, FOX, MSNBC, CBS News, and keeping an eye on the NY Times "needle." Every few moments I would turn the volume on from a different channel. As the evening wore on, the Fox correspondents started to smile more while the MSNBC correspondents started to look more dour. By midnight, it became pretty clear that Trump would prevail. I stayed up till about 3:00 in the morning after President Elect Trump's victory speech.

As I watched that speech, my concerns for the judiciary evanesced–for at least four more years. I don't pretend for a moment that efforts to destroy the Court have magically vanished. They will simply lie in wait until power is reclaimed. Indeed, the foundation for Court "reform" will continue, unabated, over the next four years. There will be a never-ending series of tweets, substacks, and podcasts about the "illegitimate" Court and the "corrupted" Justices. Make no mistake about the object of those outputs.

Where does that leave us now? The most imminent question is what happens to the Solicitor General's cases that are currently pending before the Supreme Court. Most of the federal cases are not particularly controversial, so there should be no changes. But for high-profile matters, there may be "presidential reversals." (I wrote about these flips in a 2018 article.) "Upon further reflection" is code for "upon further election." The most obvious candidate is Skrmetti. When the case was granted, I observed that the Court only took the government's petition. And this grant would leave open the possibility that a Trump DOJ could flip sides, and support the Tennessee law. At that point, what happens? A DIG? Munsingwear? Does the Court appoint an Amicus? Let the ACLU take over the case? Or does the Trump DOJ let the case ride, and see if the Court upholds the law. The case will be argued in December. I'm sure all eyes will be on Justice Gorsuch to see what he does. We remember the fallout to Gorsuch's questions in Bostock.

There may also be some pending cert petitions that the Trump DOJ withdraws. I have not taken a close study of what is on the docket. This move would not be unprecedented. In 2009, the Obama Justice Department withdrew a cert petition filed by the Bush EPA.

Oh, and speaking of the SG, I told several reporters in the past month that Elizabeth Prelogar would be the most obvious Democratic pick for a Supreme Court vacancy. Prelogar's advocacy is near-flawless, and she has a remarkable rapport with the Justices. I've rarely seen a lawyer who can connect so directly with each Justice as she speaks. During argument, she looks right at the Justices, and they look right back at her. It is a gift. She could have brought that gift to persuade her colleagues inside and outside the conference. And combined with her former boss, Justice Kagan, there would have been one helluva one-two punch. It is not meant to be, at least for now. Prelogar will find her way into private practice, and be just fine. She is forty-four now. Her window for the Supreme Court will remain open for four or maybe eight more years.

After a flurry of DOJ filings in January, the next shoe to drop will be a potential vacancy on the high court. The morning after the election, Ed Whelan wrote "I expect Alito to announce his retirement in the spring of 2025." This statement was made quite categorically. I think Ed knows something here. I told a reporter today that I would not blame Justice Alito for stepping down. He could spend time at his home on the Jersey Shore without the media trying to destroy him. Plus, his judicial legacy is set with the Dobbs decision. Indeed, the arc from his Third Circuit decision in Casey to Dobbs is a remarkable journey. If Justice Alito does decide to step down, that will immediately put forward a contest among the various Trump circuit nominees. No, I will not engage that debate here. Another time.

Ed, however, is not so sure about Justice Thomas. He writes "I hear some folks say that Thomas won't retire." I've heard much the same. One friend told me that the only way Justice Thomas leaves the Court is in a pine box. I can fully understand that point. And in candor, is there really anyone better on the lower courts than CT? Even someone thirty years younger? I'm not so sure.

Perhaps there is one carrot that could entice Justice Thomas to step down: the opportunity to serve as Attorney General. Imagine that for a moment. Clarence Thomas could be the most transformative Attorney General since Ed Meese. He could recommit the Department of Justices to the original meaning of the Constitution, in every facet of its operations. There are many federal statutes whose constitutionality would no longer be defended. Entire volumes of OLC opinions can be reviewed. Agency memoranda can be tossed in the incinerator. Statements of interest would be filed in all the right cases. And I have no doubt that the Thomas clerk network would be willing to staff each and every post in the Justice Department. It would be a veritable constitutional army. In four years, so much good could be done. Of course, I can't imagine that Justice Thomas would ever want to go through another confirmation hearing. Still, all things considered, it is worth considering. And if Thomas is not confirmed, he can go back to the job he loves.

Of course, there is also the center seat. Ed Whelan says there is a "strong possibility that Chief Justice Roberts" may step down over the "next ten or twenty years." It could happen sooner. Feel free to discount any such speculation, especially in light of my repeated calls for Roberts to resign. This position has to be exhausting. Roberts has had to shoulder more crises than any Chief Justice since the New Deal. Now is not the place to assess Robert's performance, other than to say it is a thankless task. Moreover, Roberts came to the Court with the goal of building up the institution, and having fewer 5-4 decisions. To the extent Roberts has been successful at that goal, it is by using his own vote to join the left. Roberts has had limited success in persuading others. And I doubt that task will get any easier with one or two more Trump appointees. No one would begrudge Roberts for moving on.

There is much more to write about the Court in the coming weeks and months. For now, I am just thankful the Court will remain the Court.

The post The Supreme Court After The 2024 Election appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: November 8, 1994

11/8/1994: U.S. v. Lopez argued.

Edison High School, San Antonio

Edison High School, San AntonioThe post Today in Supreme Court History: November 8, 1994 appeared first on Reason.com.

November 7, 2024

[Eugene Volokh] "Trump and the Future of American Power"

A very interesting conversation in Foreign Affairs with my Hoover colleague Stephen Kotkin. The first several paragraphs:

Stephen Kotkin is a preeminent historian of Russia, a fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution and Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, and the author of an acclaimed three-volume biography of Joseph Stalin. (The third volume is forthcoming.) Kotkin has also written extensively and insightfully on geopolitics, the sources of American power, and the twists and turns of the Trump era. Executive Editor Justin Vogt spoke with Kotkin on Wednesday, November 6, in the wake of Donald Trump's decisive victory in the U.S. presidential election.

You've written a number of times for Foreign Affairs about the war in Ukraine and what it means for the world and for American foreign policy. So let's start with an obvious question. It's impossible to know, of course, but what do you imagine Russian President Vladimir Putin is thinking right now, with Donald Trump poised to return to the White House for a second term?

I wish I knew. These opaque regimes in Moscow and Beijing don't want us to know what they think. What we do know from their actions as well as their frequent public pronouncements is that they came to the view that America was in irreversible decline. We had the Iraq War and the shocking incompetence of the follow-up, where Washington lost the peace. And we lost the peace in Afghanistan. We had the 2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession. We had a lot of episodes that reinforced their view that we were in decline. They were only too happy to latch onto examples of their view that the United States and the collective West, as they call it, is in decline and, therefore, their day is going to come. They are the future; we are the past.

Now, all of that happened before Trump. True, it looks like Trump is potentially a gift to them, because he doesn't like alliances, or at least that's what he says: allies are freeloaders. But what happened under Biden? It's not as if American power vastly increased under Biden, or under Obama, for that matter. So Trump may accelerate what Moscow and Beijing see as that self-weakening trend. But he's unpredictable. They may get the opposite. And they have revealed a lot of their own weaknesses and poor decision-making, to put it mildly.

On Ukraine, Trump's unpredictability could cut in many directions. Trump doesn't believe one thing or the other on Ukraine. And so in a way, anything is possible. It may turn out to be worse for Ukraine, but it may turn out to be better. It's extremely hard to predict because Trump is hard to predict, even for himself. You could even have Ukraine getting into NATO under Trump, which was never going to happen under Biden. Now, I'm not saying that's going to happen. I'm not saying there's even a high probability—nor am I saying it would be a good thing, or a bad thing, if it happened. I'm just saying that the idea that Trump is some special gift to our adversaries doesn't wash with me. And he may surprise them on alliances and on rebuilding American power. It might well cut in multiple directions at once.

OK, but if you had to give Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky advice right now, what would it be? …

The post "Trump and the Future of American Power" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Project Veritas' Defamation Lawsuit Against CNN Can Go Forward

Today's Eleventh Circuit decision in Project Veritas v. CNN, written by Judge Elizabeth Branch and joined by Judges Andrew Brasher and Ed Carnes, involves CNN's coverage of Twitter's suspension of Project Veritas:

On February 11, 2021, Veritas tweeted a video showing its reporters trying to interview Guy Rosen, then a Facebook vice president, outside a residence. Neither the video nor the text of the tweet accompanying the video contained any information related to the street, city, or state where the attempted interview took place. That said, a house number could be seen in the background of the video. That same day, Twitter suspended the official Veritas account on the grounds that the video violated Twitter's policy against publishing private information (informally known as a "doxxing" policy).

But CNN "suggested on-air that Twitter banned Veritas for 'promoting misinformation.'" Veritas sued CNN for defamation, and the Eleventh Circuit allowed the claim to go forward ("Taking the allegations of the complaint as true, as we must at the pleadings stage"):

We start by comparing the pleaded truth with the alleged defamation. The pleaded truth is that Twitter suspended the account of Veritas for doxing— publishing "private information [of another] without [his] consent." The alleged defamation is that [CNN anchor] Cabrera suggested on-air on February 15 that Twitter suspended Veritas's account for "promoting misinformation." Recall that Cabrera stated the following on-air:

That social media companies were "cracking down to stop the spread of misinformation and to hold some people who are spreading it accountable"; "For example, Twitter has suspended the account of Project Veritas …."; and "[T]his is part of a much broader crackdown, as we mentioned, by social media giants that are promoting misinformation." …[U]nder New York law, a defamatory statement is substantially true [and thus not actionable] if "the overall gist or substance of the challenged statement is true." Thus, the relevant question is whether the "gist" or "substance" of being suspended for "promoting misinformation" is the same as being suspended for "publishing private information of another without their consent." We conclude that it is not.

Veritas has plausibly alleged that the average viewer would conclude from Cabrera's statements that Twitter "cracked down" on Veritas and suspended it from the platform for promulgating misinformation. Cabrera's statement about misinformation would plausibly "have a different effect" on the mind of the audience than the pleaded truth—that Veritas published accurate but private information. Unlike Hustler in Guccione v. Hustler (2d Cir. 1986), which excluded the minor detail of precisely when Guccione was unfaithful to his wife but did not change the substantial truth of the accusation that he was an adulterer, Cabrera accused Veritas of substantially different behavior than that in which Veritas engaged. Under New York law, such a statement is not substantially true. Veritas committed one infraction; CNN accused it of a completely different one.

CNN resists this conclusion by contending the commentary in question was substantially true because, even if CNN had accurately identified that Veritas was suspended for violating Twitter's policy on publishing private information, the effect on Veritas's reputation in the minds of the average viewer would have been the same. In other words, according to CNN, the "gist" of the statements was true—Twitter banned Veritas as part of a broader crackdown by social media platforms more strictly enforcing content rules—and the actual reason behind the ban (be it spreading misinformation or violating a policy on publishing private information) is irrelevant because Veritas would have suffered the same reputational harm regardless of the reason.

We disagree. As we explained previously, Veritas committed one infraction—it violated a policy regarding the publishing of private information, but CNN falsely accused it of violating a completely different policy—spreading misinformation. This distinction is not an inconsequential detail….

And the court concluded that Project Veritas adequately alleged "actual malice," which is to say "that CNN 'actually entertained serious doubts as to the veracity' of Cabrera's on-air statements, or at least 'was highly aware that [her statements were] probably false'":

We need not look further than two of CNN's communications published four days prior to Cabrera's on-air statements—Cabrera's own tweet accurately reporting on Veritas's ban and the article written by Brian Fung on CNN's website. By relying on Cabrera's tweet and Fung's article in its complaint, Veritas "shoulder[ed its] heavy burden." It has plausibly alleged that CNN knew that the true reason for Veritas's suspension from Twitter was the posting of private information, but yet reported four days later on-air that Veritas had been suspended in relation to a crackdown on the spreading of misinformation…. "[A]ctual malice can be shown where the publisher is in possession of information that seriously undermines the truth of its story[.]" …

CNN contends that the article and Cabrera's tweet about Veritas's suspension are not sufficient evidence of actual malice because they do not demonstrate that Cabrera "doubted her statement" that Veritas did, in fact, "fit into" the "broader crackdown" on misinformation by social media companies. In CNN's view, for Cabrera's tweet to be evidence of actual malice, she must have subjectively known that her tweet directly contradicted her on-air statements. But CNN's argument is unpersuasive. As we have explained, at the pleadings stage, Veritas must merely allege sufficient facts to permit the inference that Cabrera published her statements with knowledge or a reckless disregard for the truth. And as we have detailed, Cabrera's February 15 statements affirmatively implied a false justification for Veritas's suspension from Twitter. Thus, Veritas has pleaded that CNN "was highly aware that the account was probably false." Whether CNN, through Cabrera or others, entertained doubts of falsity or was actually aware that Cabrera's on-air statements were false is ultimately a question for a later stage.

Judge Ed Carnes added a concurring opinion; an excerpt:

If you stay on the bench long enough, you see a lot of things. Still, I never thought I'd see a major news organization downplaying the importance of telling the truth in its broadcasts.

But that is what CNN has done in this case. Through its lawyers CNN has urged this Court to adopt the position that under the law it is no worse for a news organization to spread or promote misinformation than it is to truthfully disclose a person's address in a broadcast.

CNN makes that argument to support its position that Project Veritas cannot show actual malice because doing so requires showing reputational harm. It asserts that the difference between the alleged truth involving Project Veritas' suspension from Twitter and what CNN allegedly falsely broadcast about that suspension did not have any effect on Project Veritas' reputation. The Court's opinion assumes, for present purposes only, that actual malice does require reputational harm and holds that even if it does, reputational harm is sufficiently alleged in this case. I agree with that holding and all of the majority opinion, which I join in full.

I write separately to explain why falsely reporting that Project Veritas had been suspended from a broadcast platform for spreading or promoting misinformation satisfies any reputational harm requirement of actual malice. And that is still the case even if the reason Project Veritas had been suspended is for disclosing in a broadcast a person's house number or address.

In its district court brief in support of the motion to dismiss the defamation claim against it, CNN recounted Project Veritas' contention that there is "sufficient difference between getting kicked off [Twitter] for posting misinformation and getting kicked off for posting prohibited information to support a defamation claim by a public figure." To which CNN curtly responded: "There is not." But there is…. [T]he truth is never an immaterial detail when accusing another of misconduct, and the boundary line between truth and falsehood that CNN allegedly stepped over is more important than any line in the game of tennis.

CNN's attorney was pressed at oral argument about his "immaterial detail" and mere "foot fault" assertions. Among the questions put to him was this one: "If [CNN itself ] had to choose between being branded as someone who revealed high profile people's house numbers or being branded as an organization that spread lies, which would it choose?" After unsuccessfully attempting to duck the question, he finally answered: "I will choose we don't want to be called sources of misinformation," but he added "the difference is modest." The difference is "modest" only for those who don't value the truth as a first principle of broadcasting….

Judge Branch's opinion for the Court contains a cogent paragraph explaining that credibility and integrity are essential to journalists and news organizations, and that without truthfulness they cannot operate effectively. Dedication to truth is not merely of modest importance to a news organization: it is central, fundamental, and indispensable. False claims that a news organization spread or promoted misinformation strike at the heart of its reputation and necessarily damage its effectiveness. If actual malice does include a requirement for reputational harm, CNN's on-air statements about Project Veritas meet that requirement….

The post Project Veritas' Defamation Lawsuit Against CNN Can Go Forward appeared first on Reason.com.

[Samuel Bray] The Truth of Erasure?

If you have been following the debate about universal or nationwide remedies, you know that a lot of attention is currently being paid to the Administrative Procedure Act and vacatur. One of the most recent articles on this question is The Truth of Erasure: Universal Remedies for Universal Agency Actions, by T. Elliot Gaiser, Mathura Sridharan, and Nicholas Cordova. I have just published an analysis and response at Notice & Comment, the blog of the Yale Journal of Regulation, and you can read it here.

The post The Truth of Erasure? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] N.Y. Times on Pseudonymity in the Sean "Diddy" Combs Cases

From an article today by Julia Jacobs:

Sexual assault accusers have long sought anonymity in the courts and in the media. The flood of complaints during the #MeToo movement ushered in a much broader societal understanding of their fears of retribution and social stigmatization, and protocols in the American media that withhold accusers' names became even more entrenched ….

Securing anonymity in civil court can be much more challenging.

So far, at least two judges in Federal District Court in Manhattan have rejected requests from plaintiffs to remain anonymous in lawsuits against Mr. Combs, who has denied sexually abusing anyone….

Though U.S. civil courts are more likely to grant anonymity in sexual assault cases than other litigation — especially when the accusations involve minors — … experts said judges still often decide in favor of a defendant's argument for a fair and open trial.

In recent years, courts have rejected bids to proceed anonymously in sexual assault lawsuits against Harvey Weinstein and Kevin Spacey, citing the "constitutionally-embedded presumption of openness in judicial proceedings." …

Still, in some settings, courts have taken into account the mental anguish plaintiffs say they will experience if their names are made public — especially in an era of intense exposure on the internet — and consider the argument that declining to protect an accuser's identity could deter others from reporting sexual abuse.

The article well captures the unpredictability of the law of pseudonymous litigation, even when it comes to a pretty narrowly defined subset, such as cases alleging sexual assault: "Legal scholars say there have been broad inconsistencies in how civil courts across the country handle the issue of anonymous plaintiffs, making outcomes largely dependent on the leanings of individual judges." As it happens, the Southern District of New York, where the Combs lawsuits have been filed, tends to be especially anti-pseudonymity, though there too there is a mix of different results in similar cases.

The post N.Y. Times on Pseudonymity in the Sean "Diddy" Combs Cases appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] November 7 as Victims of Communism Day—2024

Bones of tortured prisoners. Kolyma Gulag, USSR (Nikolai Nikitin, Tass). (NA)

Bones of tortured prisoners. Kolyma Gulag, USSR (Nikolai Nikitin, Tass). (NA)

NOTE: The following post is largely adapted from last year's November 7 post on the same subject.

Since 2007, I have advocated designating May 1 as an international Victims of Communism Day. The May 1 date was not my original idea. But I have probably devoted more time and effort to it than any other commentator. In my view, May 1 is the best possible date for this purpose because it is the day that communists themselves used to celebrate their ideology, and because it is associated with communism as a global phenomenon, not with any particular communist regime. However, I have also long recognized that it might make sense to adapt another date for Victims of Communism Day, if it turns out that some other date can attract a broader consensus behind it. The best should not be the enemy of the good.

As detailed in my May 1 post from 2019, November 7 is probably the best such alternative, and over time it has begun to attract considerable support. Unlike May 1, this choice is unlikely to be contested by trade unionists and other devotees of the pre-Communist May 1 holiday. While I remain unpersuaded by their objections on substantive grounds, pragmatic considerations suggest that an alternative date is worth considering, if it can avoi such objections, and thereby attract broader support.

The November 7 option is not without its own downsides. From an American standpoint, one obvious one is that it will sometimes fall close to election day, as is the case this year. On such occasions, a November 7 Victims of Communism Day might not attract as much attention as it deserves, because many will—understandably—be focused on electoral politics instead. Nonetheless, November 7 remains the best available alternative to May 1; or at least the best I am aware of.

For that reason, I am—once again—doing a Victims of Communism Day post on November 7, in addition to the one I do on May 1. If November 7 continues to attract more support, I may eventually switch to that date exclusively. But, for now, I reserve the options of returning to an exclusive focus on May 1, doing annual posts on both days, or switching to some third option should a good one arise.

In addition to its growing popularity, November 7 is a worthy alternative because it is the anniversary of the day that the very first communist regime was established in Russia. All subsequent communist regimes were at least in large part inspired by it, and based many of their institutions and policies on the Soviet model.

The Soviet Union did not have the highest death toll of any communist regime. That dubious distinction belongs to the People's Republic of China. North Korea has probably surpassed the USSR in the sheer extent of totalitarian control over everyday life. Pol Pot's Cambodia may have surpassed it in terms of the degree of sadistic cruelty and torture practiced by the regime, though this is admittedly very difficult to measure. But all of these tyrannies—and more—were at least to a large extent variations on the Soviet original.

Having explained why November 7 is worthy of consideration as an alternative date, it only remains to remind readers of the more general case for having a Victims of Communism Day. The following is adopted from this year's May 1 Victims of Communism Day post, and some of its predecessors:

The Black Book of Communism estimates the total number of victims of communist regimes at 80 to 100 million dead, greater than that caused by all other twentieth century tyrannies combined. We appropriately have a Holocaust Memorial Day. It is equally appropriate to commemorate the victims of the twentieth century's other great totalitarian tyranny.

Our comparative neglect of communist crimes has serious costs. Victims of Communism Day can serve the dual purpose of appropriately commemorating the millions of victims, and diminishing the likelihood that such atrocities will recur. Just as Holocaust Memorial Day and other similar events promote awareness of the dangers of racism, anti-Semitism, and radical nationalism, so Victims of Communism Day can increase awareness of the dangers of left-wing forms of totalitarianism, and government domination of the economy and civil society.

While communism is most closely associated with Russia, where the first communist regime was established, it had equally horrendous effects in other nations around the world. The highest death toll for a communist regime was not in Russia, but in China. Mao Zedong's Great Leap Forward was likely the biggest episode of mass murder in the entire history of the world.

November 7, 2017 was the 100th anniversary of the Bolshevik seizure of power in Russia, which led to the establishment of the first-ever communist regime. On that day, I put up a post outlining some of the lessons to be learned from a century of experience with communism. The post explains why most of the horrors perpetrated by communist regimes were intrinsic elements of the system. For the most part, they cannot be ascribed to circumstantial factors, such as flawed individual leaders, peculiarities of Russian and Chinese culture, or the absence of democracy. The latter probably did make the situation worse than it might have been otherwise. But, for reasons I explained in the same post, some form of dictatorship or oligarchy is probably inevitable in a socialist economic system in which the government controls all or nearly all of the economy.

While the influence of communist ideology has declined greatly since its mid-twentieth century peak, it is far from dead. Largely unreformed communist regimes remain in power in Cuba and North Korea. In Venezuela, the Marxist government's socialist policies have resulted in political repression, the starvation of children, and a massive refugee crisis—the biggest in the history of the Western hemisphere. Recent events in Venezuela also highlight the dangers of "democratic socialism." While most communist regimes have taken power by force, ignorance about the history of communism and socialism could enable such movements to take power by democratic means and then eventually shut down democracy, as has actually happened in Venezuela. Victims of Communism Day can help combat such ignorance.

In Russia, the authoritarian regime of former KGB Colonel Vladimir Putin has embarked on a wholesale whitewashing of communism's historical record. Putin's brutal war on Ukraine is primarily based on Russian nationalist ideology, rather than that of the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, the failure of post-Soviet Russia to fully reckon with its oppressive Soviet past is likely one of the reasons why Putin's regime came to power, and engaged in its own atrocities.

In China, the Communist Party remains in power (albeit after having abandoned many of its previous socialist economic policies), and has become less and less tolerant of criticism of the mass murders of the Mao era (part of a more general turn towards greater repression). The government's brutal repression of the Uighur minority, and escalating suppression of dissent, even among Han Chinese, are just two aspects in which it seems bent on repeating some of its previous atrocities. Under the rule of Xi Jinping, the government has also increasingly reinstated socialist state control of the economy.

Here in the West, some socialists and others have attempted to whitewash the history of communism, and a few even attribute major accomplishments to the Soviet regime. Cathy Young has an excellent critique of such Soviet "nostalgia" in a 2021 Reason article.

In sum, we need Victims of Communism Day because we have never given sufficient recognition to the victims of the modern world's most murderous ideology or come close to fully appreciating the lessons of this awful era in world history. In addition, that ideology, and variants thereof, still have a substantial number of adherents in many parts of the world, and still retains considerable intellectual respectability even among many who do not actually endorse it. Just as Holocaust Memorial Day serves as a bulwark against the reemergence of fascism, so this day of observance can help guard against the return to favor of the only ideology with an even greater number of victims.

The post November 7 as Victims of Communism Day—2024 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Part V: The Separation of Powers

Morrison v. Olson (1988)

Morrison v. Olson (1988)  NLRB v. Noel Canning (2014)

NLRB v. Noel Canning (2014) The post Part V: The Separation of Powers appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: November 7, 1922

11/7/1922: Oregon enacts the Compulsory Education Act.

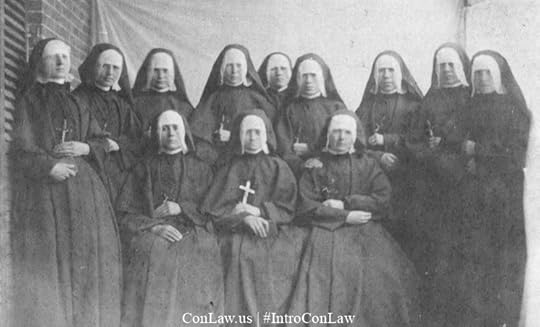

Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary

Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and MaryThe post Today in Supreme Court History: November 7, 1922 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Thursday Open Thread

The post Thursday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers