Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 229

November 10, 2024

[Orin S. Kerr] A Debate Over the Open Fields Doctrine and Fourth Amendment Law

I recently posted about the open fields doctrine of Fourth Amendment law, the rule that it is not a "search" under the Fourth Amendment for the government to trespass on to your open field. In my post, I argued that the contrary rule argued by some advocates, that passage onto a person's land should be a search, conflicts with the text of the Fourth Amendment. The constitutional language specifically protects "persons, houses, papers, and effects," and it's hard to argue, as a matter of text, that an open field is one of those four enumerated things. Open land is not a person, a house, a paper, or an effect.

Joshua Windham of the Institute for Justice has written in with a response disagreeing with me. In the interests of furthering a debate on this topic, I have reprinted his response in full below. And after that, also below, I have replied and explained why I think Mr. Windham is incorrect. Who has the better argument? You decide.

First up, here's Mr. Windham's response:

Professor Orin Kerr recently defended the "open fields" doctrine on textualist grounds. That doctrine holds that the Fourth Amendment's ban on "unreasonable searches" does not extend to land beyond the curtilage of a home. The original—and current—basis for the doctrine is that land "is not one of those protected areas enumerated in the [text]." It seems Professor Kerr agrees: "[I]f you take text seriously," he writes, "the thing searched has to be a person, house, paper, or effect" to enjoy Fourth Amendment protection. And, because land is not on that list, "you don't get protection on the land itself."

I disagree. And not just as a "policy" matter, as Professor Kerr's article suggests. As I see it, the open fields doctrine rests on an acontextual reading of the phrase "persons, houses, papers, and effects." For reference, start with what the Fourth Amendment actually says:"The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized."

Hold that text in your mind. We'll come back to it. For now, the point is simply that the Fourth Amendment contains 54 words—not merely the five words on which Professor Kerr focuses. So, what do I mean when I say that his reading is "acontextual"?

I mean that it fails to use context clues to understand what the text means—to grasp, not only what the text says (in semantic isolation), but how we're meant to understand and use it. Here's a simple example. If you walk into an elementary school classroom, you'll likely see a list of rules posted on the wall. And one rule you'll surely see is "keep your hands to yourself." How should we read the rule? Are handshakes and hugs forbidden, because that would mean touching others? Can students kick and throw things at each other, because the rule refers only to hands? No. These aren't sensible readings.

The better reading is that the rule does not exhaust, but evinces, a broader principle: Do not physically disrupt your classmates. We know that because the rule was adopted in a context: a classroom, where learning is the goal and peace is a precondition, and where it would be impossible to list out every kind of physical disruption that might break the peace. The rule doesn't specify hands because they're uniquely disruptive. It lists hands because punching is a paradigm case of the problem the rule seeks to solve. Kicking isn't listed, but if we read the rule in context, it's forbidden. Kids understand this (at least my wife, a teacher, tells me they do).

The bill of rights works the same way. Take the First Amendment. At face value, it bars only "Congress" from "abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press." But the Court has interpreted this text to bar all officials (not just Congress) from censoring most forms of expression (not just when spoken or printed). And that makes good sense. As Justice Scalia explained: "In textual interpretation, context is everything, and the context of the Constitution tells us not to expect nit-picking detail"—no less for the First Amendment's express references to "speech and press, the two most common forms of communication, [which] stand as a sort of synecdoche [or representation] for the whole. That is not strict construction, but it is reasonable construction." Antonin Scalia, A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law 37–38 (1997) (citing McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. (4 Wheat) 316, 407 (1819) (Marshall, C.J.)).

It's hard to grasp why we should read the Fourth Amendment's text any differently. But don't just take mine or Justice Scalia's word for it. The basic issue here is that we have to choose whether to treat the Fourth Amendment's reference to "persons, houses, papers, and effects" as exhaustive or illustrative. If you're a strict textualist still on the fence, look at the Ninth Amendment: "The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people." That's an explicit rule of construction, and it makes the same point I've been making here: The mere fact that the Fourth Amendment lists "persons, houses, papers, and effects" does not justify the open fields doctrine.

Of course, none of this proves that land deserves protection. But it opens the door to that conversation. While I don't have the space to give my complete argument here (for that, see my forthcoming law review article, The Open Fields Doctrine Is Wrong), I want to flag three context clues that support the inference that the Fourth Amendment protects land. Then, before wrapping up, I'd like to briefly touch on something Professor Kerr doesn't discuss: The Supreme Court's alternative justification for the open fields doctrine under the Katz privacy framework.

My first context clue is the legal status of private land at the founding. English common law held that "[e]very unwarrantable entry on another's soil the law entitles a trespass by breaking his close." Seminal search cases like Entick v. Carrington, though they typically involved homes, agreed that "bruising the grass and . . . treading upon the soil" violated the common law since "[n]o man may set his foot upon my ground without my license." And early Americans—who valued property rights and cultivation—embraced trespass protections with statutes that specified how to exclude intruders. See Buford v. Houtz, 133 U.S. 320, 328 (1890) (noting that "[n]early all the states in the early days had what was called the 'Fence Law'"). At the founding, private land was legally secure from trespass.

My second context clue is the kind of power the Fourth Amendment was meant to curb. Founding-era officials lacked freestanding search power. (See Thomas Davies's work.) If they wanted to enter property without risking trespass liability, then generally speaking, they needed a specific warrant issued by a neutral judge. (See Laura Donohue's work.) The general warrants and writs of assistance that prompted the Fourth Amendment did so precisely because they granted government officials a power they previously lacked: the power to invade property at their own discretion.

My third context clue is the Fourth Amendment's whole text. Not the five isolated words on which the open fields doctrine rests, but the 49 other words too. The first clause never says that only persons, houses, papers, and effects deserve protection. It says we have a right "to be secure in" those items "against unreasonable searches." A right to be secure entails freedom from threats or fear. (See Luke Milligan's work.) And it's not hard to see how officials roaming and placing cameras on your land might undermine your security in your person, house, papers, or effects. The second clause helps too. Because founding-era officers needed a warrant to invade property, setting the standard for valid warrants effectively set the bar for valid searches. So it's telling that, in a clause meant to do much of the Fourth Amendment's heavy lifting, we find a rule that warrants must "describ[e] the place to be searched." Isn't land a "place"?

Taking these context clues together—the fact that land was secure from trespass, that the founding generation abhorred discretionary searches, and that the Fourth Amendment's whole text sweeps more broadly than "persons, houses, papers, and effects"—I think the most reasonable inference to draw from the text is that land deserves protection. And I don't think the first clause's list undercuts that inference, either. Far from listing those items to the exclusion of everything else, it seems more plausible that the framers were merely stopping the discretionary search problem before it spread. The framers named "persons, houses, papers, and effects" because they were most recently under threat. It hardly follows that unreasonable searches of private land are constitutional. Just like it hardly follows that a rule against classroom punching allows classroom kicking.

That, in a nutshell, is why I think a more contextual reading of the Fourth Amendment's text would reject the open fields doctrine. But it's worth noting that the Supreme Court has given a second justification for the doctrine. The Fourth Amendment, at least under current precedent, protects reasonable expectations of privacy even when they are not listed in the text. The Court has held that people—categorically—"may not legitimately demand privacy" on their own land. Without getting too far into the Court's reasoning (since Professor Kerr does not rely on it), I want to make clear that I find it preposterous.

The Katz privacy test is notoriously squishy. But, by any metric, there are at least some scenarios where it's plainly reasonable to expect privacy on your own land. If we look at positive law, every state has a trespass statute—a statute that (if we indulge the fiction) reflects social expectations and says how to exclude people from your land and trigger trespass liability. If we look at personal use, people use their land for every private end they seek at home: private conversations, quiet reflection, family recreation, making art, making love, and on and on. If we look at empirical data, a 2011 study found that 66.5% of respondents believed that posting "no trespassing" signs on their land was enough to create a reasonable expectation of privacy. The point is, even if some land—like land left open to the public—doesn't deserve privacy, the Supreme Court was wrong to hold that all land beyond the curtilage fails the Katz test.

The original article to which Professor Kerr was responding urged the Supreme Court to overrule the open fields doctrine. For all the reasons above, I agree that it should. But let me stress: My interest in this issue is not merely academic. I litigate this issue all over the country. It affects millions of landowners. Earlier this year, my public-interest law firm, the Institute for Justice, published a study that found the open fields doctrine exposes at least 96% of all private land in the United States—about 1.2 billion acres—to unfettered intrusions. With deep respect for Professor Kerr, I don't believe the Fourth Amendment allows the government to wield that kind of power on so vast and terrifying a scale. 100 years of the open fields doctrine is enough.

I certainly appreciate the engagement, and I thank Mr. Windham very much for writing in. With equal respect, though, I disagree with his view. I think there are two major problems with his position.

The first problem is that I don't think there's anything particularly textualist about it. When Mr. Windham asserts a difference between an acontextual reading and a contextual reading, I think what he's really doing is comparing a textual reading and a purpose-based reading. The relevant "context" he invokes is really just the highest level of generality of his claimed purpose of the Fourth Amendment. Thus, instead of focusing on the actual language of the Fourth Amendment, he looks to "the broader principle" of the Amendment and "the kind of power the Fourth Amendment was meant to curb." It seems to me that his argument is really about the purpose of the Fourth Amendment, a purpose that he suggests is implied broadly by the text viewed holistically. On this view, the actual words are merely examples of the broader kind of problem that the provision should be interpreted to address.

That's certainly a legitimate argument, to be clear. But I don't think it's a textual argument. Rather, it strikes me as a move I have previously called "the Level of Generality game." Here's how I described it back in 2015:

Most students of constitutional law will be familiar with the Level of Generality Game, as it's a common way to argue for counterintuitive outcomes. The basic idea is that any legal rule can be understood as a specific application of a set of broad principles. If you need to argue that a particular practice is unconstitutional, but the text and/or history are against you, the standard move is to raise the level of generality. You say that the text is really a representation of one of the relevant principles, and you then pick a principle at whatever level of abstraction is needed to encompass the position you are advocating. If the text and/or history are really against you, you might need to raise the level of generality a lot, so that you get a super-vague principle like "don't be unfair" or "do good things." But when you play the Level of Generality Game, you can usually get there somehow. If you can raise the level of generality high enough, you can often argue that any text stands for any position you like.

My apologies that I expressed the idea rather dismissively above. I wouldn't have used that tone in this context if I were making the point for the first time here. But I think it's fair to say that this is the basic structure of Mr. Windham's argument. Of course, some will argue that the Level-of-Generality strategy is a perfectly fair move to play, and that the Supreme Court sometimes does play it. And indeed, it does! But it doesn't strike me as a textualist argument. Rather, it's the classic move to get around inconvenient text.

The second problem with Mr. Windham's argument runs along more originalist lines. In his telling, you can interpret "persons, houses, papers, and effects" as merely illustrative examples of protected things, rather than a complete list of the covered things, because those were the things to be protected that were on the drafters' minds. In Mr. Windham's telling, "the framers named 'persons, houses, papers, and effects' because they were most recently under threat." I take the suggestion to be that, if the Fourth Amendment's drafters had explicitly considered the possibility of writing the Fourth Amendment to cover land, they likely would have. On this view, we should interpret the Fourth Amendment in terms of what we think the framers would have said if they had thought about the question, rather than the particular words that they wrote.

Putting aside that this sort of speculation does not seem textualist, either, this specific argument runs into a problem. The drafters of the Fourth Amendment actually did consider a broader version of the text that would have covered open fields. And they rejected it.

Here's the history, as I understand it. In 1789, James Madison introduced what would become the Fourth Amendment. Madison's initial proposed text was as follows:

The rights to be secured in their persons, their houses, their papers, and their other property, from all unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated by warrants issued without probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, or not particularly describing the places to be searched, or the persons or things to be seized.

Notice what was protected in Madison's original draft. Madison's language protected their persons, their houses, their papers, and their other property. "Their other property" is a really broad phrase. It would presumably have included everything a person owned, including their open land.

The Committee in charge of considering Madison's draft changed the language, however, from "other property" to "effects." Here's my discussion of that change from a recent article:

The Committee of Eleven, made up of representatives of each state, slightly altered the language. Unfortunately, no explanations exist for why the changes were made. But three changes stand out. First, and most significantly, the phrase "other property" was replaced with "effects." That is, the new language offered protection to the people in their persons, houses, papers, and "effects" instead of in their persons, houses, papers, and "their other property." Dictionaries of the era defined "effects" as "personal property, and particularly . . . goods or moveables."

Critically, "effects" were property that excluded real property—that is, it excluded land. In other words, the drafters took language that would have included open fields and replaced it with language that excluded open fields. We don't know why, and I personally don't think it matters why. But to the extent an argument hinges on what the drafters might have had in mind, it doesn't seem very faithful to that to adopt an interpretation that the drafters rejected.

One final thought. Mr. Windham invokes Justice Scalia for the idea that the language "persons, houses, papers, and effects" should be interpreted to include open fields. It's worth noting, though, that Justice Scalia was on my side of this debate, not Mr. Windham's. Here's what Justice Scalia wrote about the open fields doctrine in United States v. Jones:

Quite simply, an open field, unlike the curtilage of a home, see United States v. Dunn, 480 U. S. 294, 300 (1987), is not one of those protected areas enumerated in the Fourth Amendment. Oliver, supra, at 176–177. See also Hester v. United States, 265 U. S. 57, 59 (1924). The Government's physical intrusion on such an area—unlike its intrusion on the "effect" at issue here—is of no Fourth Amendment significance.

Justice Scalia had it right, I think.

The post A Debate Over the Open Fields Doctrine and Fourth Amendment Law appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "Democrats Have Been Acting Like the Proverbial American Tourist in France, …

A great line from Chuck Lane (Washington Post). Just to be clear, it is easy to imagine Republicans doing the same in a future election.

The post "Democrats Have Been Acting Like the Proverbial American Tourist in France, … appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Can The Federal Courts Still Tar Trump With The Brush of Bigotry Against Muslims and Hispanics?

There was a constant theme in the #Resistance litigation during President Trump's first term in office: he is a bigot, and everything he does is tainted by bigotry. The prime example was the travel ban. Federal judges in Hawaii, Maryland, Brooklyn, and elsewhere gleefully cited President Trump's tweets to show that he had animus against Muslims. As I wrote at the time, they tarred Trump with the brush of bigotry. Similar reasoning was raised in the challenge to the cancellation of DACA. The New York Attorney General argued that the policy could not be wound down due to Trump's animus against Hispanics. The AG cited Trump's interview with Jorge Ramos, lines about "bad hombres," and countless other tweets. At the time, I wrote that even if these "comments should have given pause to his voters, courts cannot properly consider them in evaluating this policy."

Now, as the second term begins, the #Resistance is already starting to whirl again. But will these same animus arguments work? Can California and New York and Maryland once again argue that everything Trump does is tainted by bigotry against Hispanics and Muslim people? Is Trump perpetually tainted? I'm sure they'll try to make that argument. But there is some countervailing evidence. The 2024 election returns!

For starters, Trump won the most votes in Dearborn, Michigan, the city with one of the highest Arab populations in the country!

Unofficial results released by the city of Dearborn show that Mr. Trump won 42 percent of the vote in Dearborn, compared with 36 percent for Ms. Harris and 18 percent for the Green Party candidate, Jill Stein.

In 2020, similar results released after the election showed that Mr. Biden had won almost 70 percent of votes by Dearborn residents. . . .

This week, the sentiments of Arab and Muslim Americans in Dearborn were heard through the ballot. In interviews with The Times on Tuesday outside polling stations, voters backing Mr. Trump said they wanted to give him a chance to rein in wars across the world and bring peace to the Middle East.

Despite everything that we have been told over the past decade, a significant share of Muslim voters chose Donald Trump over Kamala Harris. Certainly they know more about Muslim animus than some cloistered judges on the Acela corridor.

The trends were even greater for Hispanic voters:

President-elect Donald Trump was backed by 46% of Latino voters Tuesday, surpassing Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush to win the biggest share of the national Latino vote by a Republican presidential contender in modern times, a new exit poll shows.

These mini vignettes concretize how much the #Resistance movement overplayed their hand. Calling Trump a bigot every day for a decade has had no actual impact on voters. None. The Times observed regarding Muslims:

Many voters brushed aside comments Mr. Trump has made that were critical of Muslims, and some of them cited his willingness to visit Dearborn and bring prominent local Muslim leaders onstage at a recent campaign rally as evidence of an olive branch.

And Axios reported about Hispanics:

Latino voters appeared to look beyond the racist rhetoric Trump's used to describe undocumented immigrants in an election in which the economy and inflation were top concerns of many voters.

All of the attacks on Trump were mostly noise. It was Lawfare designed to cripple a presidency. Yet during the first term, courts sopped this slop up.

What happens in Trump's second term? You might say that courts should not take cognizance of electoral returns. I agree, and I'll raise you one more: courts should have never performed a "judicial psychoanalysis of [Trump's] heart of hearts," to quote McCreary County. But psychoanalyze they did. And if judges are going to go off script, they may as well consider improper evidence that supports Trump.

The post Can The Federal Courts Still Tar Trump With The Brush of Bigotry Against Muslims and Hispanics? appeared first on Reason.com.

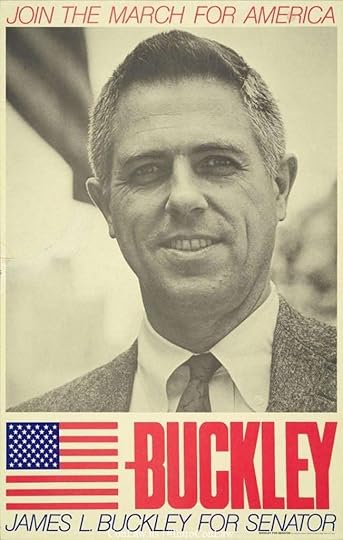

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: November 10, 1975

11/10/1975: Buckley v. Valeo argued.

Senator James Buckley

Senator James BuckleyThe post Today in Supreme Court History: November 10, 1975 appeared first on Reason.com.

November 9, 2024

[Eugene Volokh] Court Blocked Videorecording of Voters (Among Other Behavior)

From Judge Terrence Berg's opinion on Election Day in ACLU of Mich. v. Does 1-6:

The ACLU asserts that Defendants are actively engaged in activities to threaten, intimidate, harass, and deter voters from participating in the 2024 election. The ACLU submitted four affidavits from Michigan residents in support….

Raimi served as a poll watcher on Election Day in four different locations. At the polling location in Derby Middle School, Birmingham, Raimi saw three men with cameras who had been filming people going into and out of the polling station. One of them was wearing a baseball cap that said "DON'T ANNOY ME, I'M AN ASSHOLE. MY RIGHTS DON'T STOP WHERE YOUR FEELINGS START." The other two were described as wearing "patriotic" shirts. Raimi told them they could not film people coming in and out of a polling location, but they responded that it was their First Amendment right to film.

Other people passing out flyers near the polling station told Raimi that the three men had blocked a family from leaving the polling station, despite the family asking them not to record them. At the polling station at Oakland Schools Technical Campus Southeast, in Royal Oak, Michigan, Raimi saw one of the same three men who had been filming. The man was now wearing a gaiter that covered his nose and mouth and was accompanied by three other individuals who appeared intimidating to Raimi. Raimi indicated the individuals had cameras and were filming the polling location.

The precinct supervisor instructed the men not to film but they once again stated that it was their First Amendment right to record. Raimi told them not to film as well but was met with the same response. The police arrived, and the individuals left 10 to 15 minutes later, though two of them continued filming the movements of the police as they departed. Raimi believes the individuals were part of an organized effort to invite negative responses or anger from poll workers and voters and to capture these responses on video. …

Ago averred that she also went to vote at the Oakland Schools Technical Campus in Royal Oak, Michigan, around 2:00 p.m. on November 5, 2024. When she arrived, she saw two men and one woman recording voters using their phones. The men wore masks covering their faces from the nose down. Ago averred that she heard poll workers tell the individuals in question to leave. The individuals responded that they were permitted to film because they were part of the "media." Ago heard a poll worker call the police.

As Ago went to vote, one of the masked men approached her and stood four or five feet away, filming. A poll worker told the masked man to back away, as did Ago, but the man refused. Ago said that she had a right to privacy while she voted, but the man responded: "You don't have a right to privacy while you're voting, I'm not moving."

Ago stepped out into the hallway because she was intimidated. The masked man stepped into the hallway, and Ago went back inside the polling area and voted. Ago left, and told a police officer about what happened to her. Ago reported that she drove by the polling place one hour later, and saw that while police cars were outside the building, the three people who had been filming her and the other voters were still standing outside of the polling place….

Feldberg averred that she voted at the First Presbyterian Church in Birmingham, Michigan, on November 5, 2024, around 1:00 p.m. Feldberg averred that at around 1:10 p.m., five white men and one white woman arrived in the hallway outside the polling room. One man wore an American flag bandanna over his face, while the others did not have their faces covered. Feldberg averred that one man had a short beard and a black shirt, another wore a green shirt and had a grey beard, and another wore an orange vest and had a short beard. Feldman averred that the men and the woman had phones with cameras which were recording video, and that the men and the women used "selfie sticks" to insert their phones into the polling room. One of the people stepped into the polling room, but only by around a foot. All "linger[ed] as a group" in the entryway to the polling room, and were loud and made noise.

Feldberg averred that because the group was blocking the door, voters had to "almost push past" the group to get into the polling room. Feldberg voted, then left the polling room. One of the men in the group then followed Feldberg into the hallway. Feldberg told the man, "[t]his is why we vote." The man then put his phone a foot away from Feldberg's face, prompting Feldberg to tell him that he did not have her permission to film her. The man responded: "Your request has been denied." The woman in the group chimed in: "Oh, look at the reaction on her." Feldberg averred that she went back into the polling room to be with her daughter. Meanwhile, the group of people continued to film voters. Voters asked why the group of people were there.

Feldberg told a poll worker that she was not comfortable walking to her car. The poll worker responded by saying they had called the police, and asked if Feldberg wanted someone to walk her out. Feldberg agreed, and had a poll worker walk her out using a different exit. As Feldberg got to her car, Feldberg saw the group of people following another voter to his car, and saw that they were filming Feldberg as well.

Feldberg averred that after this experience, she reported these events at a police station. Feldberg averred that the police told her that the group of people had not done anything illegal, and that there was not anything that the police could do "because it was free speech in a public place."…

Executive Director of the ACLU[] Khogali asserted that the ACLU has been informed by two witnesses, including one voter and one poll worker, that a group of 6 individuals have been visiting multiple polling locations in Oakland County, entering buildings where polling was going on, and filming voters coming and going against their will, including following voters to their cars while filming them, while refusing to stop filming when asked. Some voters have been sufficiently intimidated that they have sought to escape the polling station through alternate paths. The ACLU has had to divert resources to respond to and document voter intimidation that took place in Oakland County thereby reducing the amount of volunteers and financial resources the ACLU could use towards core Election Day services for voters….

The court didn't offer much detailed analysis (possibly because this case was being decided in the span of hours), but here's what it concluded:

Defendants are ordered to cease the harassment or intimidation of voters at or outside of the polls during the November 2024 Election—including filming voters coming and going from the polls, coming within 100 feet of the entrance to any polling station or necessary points of ingress or egress from a polling station, following individuals to or from their cars to the polls, or any other form of menacing or intimation of violence while wearing a mask or otherwise….

No papers were filed by the defendants, and I'm not sure whether they even received prior notice that would allow them to file papers or present their positions. (You can see the ACLU's legal argument here.) The court scheduled a preliminary injunction hearing, but it was then canceled because the ACLU dismissed the case the day after election day; of course, once the election was over, there was little left to be done.

Note that lower courts have generally concluded that the First Amendment includes a right to videorecord in public places, at least when the recording is of public officials (such as police officers). The logic of those cases suggests that this right to gather information would include the right to videorecord even private citizens in public places; but that question remains unsettled, as does the question of whether such recording can be limited in particular contexts, or places.

Finally, note that the Court has upheld laws that limit electioneering within 100 feet of polling places, and Michigan does have ; but the injunction here seems to limit "filming voters coming and going from the polls" even when the filming is done from outside the 100-foot bubble zone.

The post Court Blocked Videorecording of Voters (Among Other Behavior) appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] The Penis Pancake

From Florida Administrative Law Judge Gary Early's Oct. 31 recommended order in Turnage v. Bob Evans Restaurant, LLC, considering the question "Whether Respondent discriminated against Petitioner in a place of public accommodation due to his race or sex through an act of sexual harassment in violation of section 760.08, Florida Statutes":

On January 3, 2024, Petitioner, through his counsel, Bernard R. Mazaheri, filed a Charge of Discrimination with the Florida Commission on Human Relations (FCHR) alleging that Respondent, Bob Evans Restaurant, LLC, discriminated against him by serving him a pancake "shaped into a penis and balls." {A photograph of the pancake was included in the Charge of Discrimination. Unless Petitioner was advised that it was intended to depict a penis, it could just as easily be a pancake-based representation of an elephant, or when viewed from a different angle, the capitol building of the state of Florida.} …

Petitioner, through his counsel, chose to invoke the jurisdiction of DOAH to contest the decision by FCHR that being served a pancake allegedly in the shape of a penis did not rise to an actionable case of discrimination. Respondent joined the fray by having its counsel make an appearance as a qualified representative.

One might conclude that two attorneys, both presumably bound by canons of professional conduct, would pay attention to a notice setting a hearing in a case they brought or participated in. Here, that did not occur. Instead, the parties, and their counsel, decided it to be appropriate to ignore the hearing, thus wasting the time of the presiding Administrative Law Judge and the court reporter, and allowing the taxpayer dollars used to pay both to be wasted. Despite having knowledge of these proceedings, the parties, through their counsel, failed to comply with the Notice of Hearing or the Order of Pre-Hearing Instructions, and failed to appear at the final hearing.

Based on Petitioner's failure to appear and offer evidence, there is no evidentiary basis on which findings can be made that Bob Evans Restaurant engaged in any discriminatory conduct….

The post The Penis Pancake appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: November 9, 1942

11/9/1942: Wickard v. Filburn decided.

The Stone Court (1941-1942)

The Stone Court (1941-1942)The post Today in Supreme Court History: November 9, 1942 appeared first on Reason.com.

November 8, 2024

[John Ross] Short Circuit: A Roundup of Recent Federal Appeals Court Decisions

Please enjoy the latest edition of Short Circuit, a weekly feature written by a bunch of people at the Institute for Justice.

Friends, the Supreme Court is conferring this very day about whether to take up Baker v. City of McKinney, which asks the question: If a SWAT team blows up an innocent person's house to apprehend a fugitive, who pays for the damage? The unlucky homeowner or the public as a whole? Defying fairness, justice, and 150 years of Supreme Court precedent, last year the Fifth Circuit went with the former. Click here to learn more.

This week on the Short Circuit podcast: A 20-word victory at SCOTUS about walking on the wrong side of the road.

Federal employees: The debt limit is unconstitutional! First Circuit: Every time default looms, Congress swoops in and saves the United States' credit, just like MacGyver. Who's to say it won't again in the next episode? Your injury is thus entirely speculative, and your case is moot. Come back after the apocalypse and then perhaps we can talk. Allegation: Jamaican gang terrorizes man and his family for political reasons. He's framed him for murder; a warrant is issued. He flees to the U.S. and is arrested. Man: If I'm deported, I face additional torture! First Circuit: There was probable cause for the warrant, so no asylum. But you might have a shot under the Convention Against Torture on remand. After 1 a.m., Collingdale, Penn. police officer tries to pull over suspected stolen car, but the driver speeds off. Forty minutes later, the officer sees the car again, and this time it pulls over. The officer draws his weapon, waits for backup, and then all three occupants are ordered out at gunpoint. They comply. A frisk uncovers a gun magazine. A look into the trunk yields evidence connecting the group to a string of armed robberies. Suppress the evidence? Third Circuit: No. Dissent: The record does not support the officer's belief that the driver tried to evade him, and cops can't just pull people out of vehicles at gunpoint or frisk them based on a hunch. In which the former CEO of a Dallas-based investment firm mired in bankruptcy proceedings petitions for mandamus to recuse the presiding bankruptcy judge. Fifth Circuit: The judge's two novels do not display an impermissible bias, even though one of them ( Hedging Death ) involves a Dallas-based investment fund. Nor does the fact that the judge has sometimes said disobliging things about the CEO, since those disobliging things are supported by the record. Pro se allegations: Supervisor at Abilene, Tex. jail asks inmate to record gang member confessing to murder but declines to inform guards, who can't be trusted not to out informants. Yikes! The guards discover the inmate's recording device. A gang member assaults the inmate, leaving him with a broken nose and persistent headaches that have gone untreated. Fifth Circuit (unpublished): His failure-to-protect claim against the supervisor should not have been dismissed. [NB: Experts agree that on remand he actually has a decent shot at overcoming qualified immunity because the Fifth Circuit is on the side of the circuit split that doesn't require a totally identical prior case when the claims don't involve split-second decisions. Read all about the split-second split in IJ's petition for certiorari in Martinez v. High .] The Michigan Court of Claims consists of judges from the Michigan Court of Appeals. Appeals from the former court go to the latter court (although the same judges don't review their own cases). Michiganders who lost cases in the Court of Claims argue this violates their due process rights because judges might go soft on their fellow judges' rulings. Sixth Circuit: Interesting theory, although SCOTUS justices used to do the same thing by riding circuit, and in 1803 they said that was OK. Anyway, you sued the wrong people. In 2017, Detroit police set up a perimeter around a gas station after a hand grenade is discovered sitting next to the pumps. Oh no! There's heavy fog and a man pops into the station unaware of the police presence. Officers scream profanities at him, don't identify themselves as law enforcement, and then handcuff him despite his protestations that he is … also a police officer. He files a complaint. Sixth Circuit (2021): Could be the dept. retaliated against him for that. Sixth Circuit (this week, unpublished): No need to disturb the jury's verdicts in his favor on that claim and the claim that the handcuffs were too tight. Does police officers' use of a "pole camera" to film the front of someone's home amount to a search under the Fourth Amendment? Seventh Circuit (2021): No. Seventh Circuit (2024): Still no. Concurrence: On a blank slate, I'd say yes. (IJ has some thoughts on all this too.) Allegation: Witness reports man slamming woman's head against a metal railing outside apartment. LAPD officers arrive and find the man with scant injuries and the woman beaten to a pulp. She says she wants to press charges but changes her mind after an officer tells her that she'll be arrested if she does—because the man claimed she was the aggressor. Which is doubly false: The man hadn't said that and, even if he had, state law discourages the arrest of domestic violence victims who have been beaten to a pulp. Ninth Circuit (unpublished): The woman's First Amendment retaliation claim against the officer should not have been dismissed. Arizona prison inmate and "adherent to the Christian-Israelite beliefs" requests that he be allowed to eat the "certified kosher-for-Passover" prison diet, which he claims is mandated by his religious faith. Prison chaplain: Prove it. Ninth Circuit: That is exactly the sort of inquiry into the correctness of a person's religious beliefs that the First Amendment forbids. California woman challenges ALJ's denial of her request for Social Security disability benefits and wins. Not only does she win, but the district court concludes that the Social Security Administration's position was not "substantially justified" and awards her attorneys' fees under the Equal Access to Justice Act. But it holds that she cannot recover fees for alternative legal theories the district court did not reach in ruling for her. Ninth Circuit: Give her all of the fees. In 2021, President Biden issued an executive order directing federal agencies to include a clause in federal contracts requiring contractors to pay employees a $15 minimum wage. Five states—which sometimes act as federal contractors and had to pay higher wages as a result of the requirement—file suit. Feds: The purpose of the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act is to promote economy and efficiency in federal procurement, and the president can implement any policy he thinks does that. Ninth Circuit (over a dissent): He can implement policies to carry out the operative provisions of the FPASA, not any policy that's merely consistent with the law's purpose. No operative provision grants authority to impose a wage requirement. Class of student loan borrowers sues the Department of Education, upset about the dept.'s backlog of hundreds of thousands of unprocessed applications for borrower defense relief. As the two sides move towards settlement, the dept. produces a list of 151 schools whose students should presumptively get relief based on "strong indicia regarding substantial misconduct" by the schools. Three of the for-profit universities on the list object to the settlement and seek to intervene, arguing that including them on the list damaged their reputation. Ninth Circuit: The schools have Article III standing, but not prudential standing, so we lack jurisdiction to review the settlement. Dissent: They do have prudential standing, we do have jurisdiction, and the settlement was unlawful. In 2023, Colorado raised the minimum age to purchase a firearm from 18 to 21. (Possessing, using, or acquiring one by gift or inheritance remains legal.) Tenth Circuit: The injunction preventing the law from going into effect is dissolved. Concurrence: And please do scroll on down to page 92 for a big list of state laws (enacted both before and after 1900) imposing similar restrictions. Black-tailed prairie dogs and sundry friends and relations live in the Thunder Basin National Grassland in Wyoming. It's been proposed that the endangered black-footed ferret be reintroduced to reside there as well. After many years of planning, however, the prairie dogs were hit with a massive plague epidemic, leading to a revised plan for prairie dog management and ferret introduction. Environmental groups sue, claiming the plan was most unhelpful to our furry friends. Tenth Circuit: And they have a point. Go back and give a "hard look." Dissent: The Forest Service already did that. Montgomery County, Ala. clerk's office issues warrant for failure to appear for a probation meeting. The targeted man then meets with his probation officer, who tells him everything's cool and he's "free to go." Four years later he's arrested and held without a hearing—for 48 days. During which time his car is repoed, he defaults on a loan, and his roommate sells some of his stuff. He sues the jailers. District court: Who don't get qualified immunity. Eleventh Circuit (unpublished): We maybe would immunize you guys, but your defense counsel conceded so much stuff both below and at oral argument here that we need to dismiss the appeal. Good luck at trial. Terminated public university employees in Georgia sue for discrimination and retaliation under Title IX, which doesn't expressly allow private lawsuits for sex discrimination in employment. Did Congress nevertheless intend to provide a right to sue? Eleventh Circuit: No. Title VII already has clear remedies for employment discrimination. Congress likely didn't want Title IX—which handles discrimination mostly by withholding federal funding—to create a workaround for claims already within Title VII's detailed scheme. And in en banc news, the Fourth Circuit will reconsider its decision that it wasn't a "search" when law enforcement got a "geofence warrant" for cell-phone data from Google that placed the defendant with 150 meters of a bank and which led to his conviction for armed robbery. And in more en banc news, the Sixth Circuit will reconsider its decision that an Ohio school district's policy barring students from intentionally using another student's non-preferred pronouns passes muster under the First Amendment.With winter approaching, Kalispell, Mont. officials recently shut down the Flathead Warming Center, a nonprofit homeless shelter. Asked by a federal judge where he expects people to sleep, the mayor replied, "They have to go back into the trees." But good news! This week, the center won a preliminary injunction that will allow it to continue providing warm beds (just as nighttime temps drop into the 20s) while its constitutional claims against the city proceed. We look forward to proving, among other things, that the center is a good neighbor that's being scapegoated by officials (who really should be focusing their attentions on the skyrocketing price of housing). Click here to learn more.

The post Short Circuit: A Roundup of Recent Federal Appeals Court Decisions appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Part VI: Slavery and the Reconstruction Amendments

Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) The History of the 13th and 14th Amendments The Privileges or Immunities Clause

Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) The History of the 13th and 14th Amendments The Privileges or Immunities Clause  The Slaughter-House Cases (1873)

The Slaughter-House Cases (1873)  Bradwell v. Illinois (1873)

Bradwell v. Illinois (1873)  U.S. v. Cruikshank (1876)

U.S. v. Cruikshank (1876)  The Slaughter-House Cases (1873) The Enforcement Powers of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments

The Slaughter-House Cases (1873) The Enforcement Powers of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments  Strauder v. West Virginia (1880)

Strauder v. West Virginia (1880)  The Civil Rights Case (1883) The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

The Civil Rights Case (1883) The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment  Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886)

Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886)  Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)

The post Part VI: Slavery and the Reconstruction Amendments appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] It's Frivolous to Sue a Party for Supposedly Not Living Up to Its Name

From last week's decision by Judge Angel Kelley (D. Mass.) in Kersey v. Republican National Committee:

In this closed case, plaintiff George Kersey, who represents himself, argued that the political stance of the Republican National Committee is inconsistent with its name. The Court dismissed the case as frivolous ….

Kersey tried to appeal, and to decide whether he was entitled to, the court had to consider whether to waive the filing fee (based on Kersey's poverty). No, said the court, because "Kersey's appeal is frivolous":

No reasonable person could believe that his claim, which argues for the Republican Party to change its name to better align with its platform, has any legitimate legal basis. The Court previously explained that political parties have the First Amendment right to choose their own names, ideologies, and candidates.

Seems quite correct for me, as to Republicans, Democrats, Libertarians, Peaceniks & Freedomers, and even the Rhinoceroses.

The post appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers