Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 222

November 21, 2024

[Josh Blackman] Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi's Role in NFIB v. Sebelius

President Trump's new nominee for Attorney General is Pam Bondi, the former Florida Attorney General. I wrote about Bondi in some detail for my 2013 book, Unprecedented: The Constitutional Challenge to Obamacare.

Florida Attorney General Bill McCollum left office on January 3, 2011. Five months earlier, he had lost the Florida Republican gubernatorial primary to the eventual winner, Rick Scott. His bid to win the governor's mansion by opposing Obamacare didn't pan out. In fact, most of the attorneys general who joined the suit in Florida in 2010 were unsuccessful in obtaining higher office. South Carolina Attorney General Henry McMaster, who began the initial challenge against the Cornhusker Kickback, lost his bid for the governorship in 2010. Nebraska Attorney General Jon Bruning withdrew his candidacy for the Senate. Washington Attorney General Robert McKenna was defeated in the governor's race in 2012. Only Pennsylvania Attorney General Tom Corbett would go on to win the governor's mansion in Harrisburg in 2010.

McCollum was replaced by the newly elected Pam Bondi. Shortly before [District Court Judge] Vinson's opinion was issued [in February 2011], Bondi was faced with her first decision: should the twenty-six states involved in the suit obtain new counsel or stick with David Rivkin? For Bondi, the NFIB's hiring of Jones Day "accelerated the decision to switch." Looking ahead to the eventual end game, an attorney from the Florida Attorney General's office told me that the key question would be "who would argue at the Supreme Court."

Bondi was not as fond of Rivkin as McCollum was. More importantly to Bondi, Rivkin had never argued before the Supreme Court. Though it was an "agonizing decision" to "switch horses," the attorney general decided "it was not going to be Rivkin." All of the other attorneys general agreed to change counsel. Rivkin understood the decision and took it graciously, calling it a "typical Washington thing."

Bondi wanted "the best chance to win" the case with a top Supreme Court litigator. At its beauty contest, Florida interviewed over a dozen potential Supreme Court advocates. Florida did not consider Ted Olson of Gibson, Dunn, & Crutcher, who was President Bush's solicitor general and had argued Bush v. Gore and dozens of other cases before the Court. Despite his prolific record for conservative legal causes, Olson's work in challenging the constitutionality of Proposition 8 and supporting same-sex marriage was a red flag and cause for concern among the Republican attorneys general. Otherwise, Olson "would have certainly been in the running." Florida considered Maureen Mahoney and Gregory Garre of Latham & Watkins, as well as Bartow Farr (who would ultimately be appointed by the Supreme Court to argue an issue the government abandoned).

Eventually, the contest was narrowed down to three finalists: Paul Clement of Bancroft PLLC; Miguel Estrada of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher; and Chuck Cooper of Cooper & Kirk.

Bondi flew to Washington to personally interview Clement. She "really liked [Clement's] demeanor" and thought he "had it all." With fifty arguments before the Court and an "incredibly eloquent" style, he was the "package deal." There was "no question" that Clement, and his superlative associate Erin Murphy at Bancroft, would be the team. Bondi told Supreme Court reporter Joan Biskupic that Clement "shared our passion, and he was confident we could win." And he came with an attractive price tag. The states gave Clement a flat fee of $250,000 to be shared by the twenty-six states.

And the rest is history.

The post Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi's Role in NFIB v. Sebelius appeared first on Reason.com.

[Mark Movsesian] A City upon a Hill

Let's take a quick detour from the usual VC topics to talk about something a bit older—400 years older, to be exact. It's a Puritan text from Massachusetts, which makes it perfect for Thanksgiving. (Yes, I know the Puritans aren't the same as the Pilgrims. Stick with me here.)

This text has echoed across centuries, its meaning changing in fascinating ways. And it offers an unexpected window into today's debates over original versus traditional meaning.

You've probably heard American leaders refer to the United States as a "shining city upon a hill." The phrase became a political staple thanks to Ronald Reagan in the 1970s and 80s. But Reagan didn't invent it. He borrowed it from John Winthrop, the 17th-century governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, who got it from the Gospel of Matthew.

Winthrop used the phrase in 1630 in an essay titled A Model of Christian Charity. He wrote it either onboard the Arbella on his way to America or just before leaving England—historians aren't entirely sure. His goal? To describe the high stakes of the Puritans' mission in the New World. "For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill," Winthrop wrote. "The eyes of all people are upon us."

The idea of America as an exceptional, world-altering place has stuck with us. But, as I discuss in a recent Legal Spirits podcast with Notre Dame historian Don Drakeman, the meaning of "city upon a hill" has changed dramatically.

For Reagan, Winthrop was a "freedom man," and the city symbolized a refuge for people seeking freedom. Reagan's version wasn't just about liberty, though; it was a point of national pride. He described the city as "a tall, proud city built on rocks stronger than oceans, wind-swept, God-blessed, and teeming with people of all kinds living in harmony and peace." It was a place of open doors, bustling commerce, and boundless opportunity.

It's a nice image—but totally unlike the original. True, Winthrop and the Puritans sought freedom, but not in Reagan's sense of commerce and individual liberty. Their vision was static, hierarchical society, united by Christian love. They weren't tolerant of religious disagreement and would not have seen intolerance as a failing. All kinds of people? They didn't even welcome other English Protestants.

And Winthrop's "city upon a hill" wasn't a boast—it was a warning. If the Puritans failed to uphold their covenant with God and show Christian love, their mission would fail. They wouldn't be a shining example. They'd be a cautionary tale, "a story and a by-word through the world."

Just now, constitutional scholars are debating the difference between original and traditional meaning. A Model of Christian Charity isn't a binding legal text, of course, but it seems to me it offers a nice example of the issues in the constitutional debate.

Think of A Model of Christian Charity as expressing the "original meaning." Winthrop's understanding is clearer than many original meanings, in fact. The Reagan-era version—the one most Americans know today—represents the "traditional meaning" that's evolved over time. And that meaning itself is 50 years old—which is reasonably old, in a country that dates back only 250 years.

So, which one is "correct"? The original meaning, or the meaning Americans have come to understand over time?

I dig further into all this in my recent Legal Spirits episode with Don Drakeman. You can check it out here.

The post A City upon a Hill appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Checks and Balances Work: Matt Gaetz Withdraws from AG Nomination

From Gaetz's Tweet; "the incredible support of so many" is the usual marketing-speak, whether in politics or in business, but the "thoughtful feedback" (coupled with "so many" making clear that there were others) signals the truth well, I think:

I had excellent meetings with Senators yesterday. I appreciate their thoughtful feedback—and the incredible support of so many. While the momentum was strong, it is clear that my confirmation was unfairly becoming a distraction to the critical work of the Trump/Vance Transition. There is no time to waste on a needlessly protracted Washington scuffle, thus I'll be withdrawing my name from consideration to serve as Attorney General.

Of course, it would have been better if there had been no need for checks and balances here; but it's good to see them working. (The checks here, of course, are primarily the Senate, but closely tied to the freedom of public criticism and the eventual prospect of pushback at the ballot box.)

Obligatory hat tip to good ol' Jimmy (or was it Sasha Alex?):

[T]he great security against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department, consists in giving to those who administer each department the necessary constitutional means and personal motives to resist encroachments of the others. The provision for defense must in this, as in all other cases, be made commensurate to the danger of attack.

Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place. It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature?

If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.

A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions. This policy of supplying, by opposite and rival interests, the defect of better motives, might be traced through the whole system of human affairs, private as well as public. We see it particularly displayed in all the subordinate distributions of power, where the constant aim is to divide and arrange the several offices in such a manner as that each may be a check on the other that the private interest of every individual may be a sentinel over the public rights. These inventions of prudence cannot be less requisite in the distribution of the supreme powers of the State.

UPDATE: Quote enlarged a bit, to include the first two paragraphs (I had originally started it with "If men were angels").

The post Checks and Balances Work: Matt Gaetz Withdraws from AG Nomination appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "Far from Representing a Powerful Avant-Garde Leading the Way to Political Change, …

From Prof. Michael W. Clune, in the Chronicle of Higher Education; the whole piece is much worth reading, but here's one passage:

The second problem with thinking of a professor's work in explicitly political terms is that professors are terrible at politics. This is especially true of professors at elite colleges. Professors who — like myself — work in institutions that pride themselves on rejecting 70 to 95 percent of their applicants, and whose students overwhelmingly come from the upper reaches of the income spectrum, are simply not in the best position to serve as spokespeople for left-wing egalitarian values.

As someone who was raised in a working-class, immigrant family, academe first appeared to me as a world in which everyone's views seemed calculated to distinguish themselves from the working class. This is bad enough when those views concern art or esoteric anthropology theories. But when they concern everyday morality and partisan politics, the results are truly perverse.

In return for their tuition, students are given the faculty's high-class political opinions as a form of cultural capital. Thus the public perceives these opinions — on defunding the police, or viewing biological sex as a social construction, or Israel as absolute evil — as markers in a status game. Far from advancing their opinions, professors in fact function to invalidate these views for the majority of Americans who never had the opportunity to attend elite institutions but who are constantly stigmatized for their low-class opinions by the lucky graduates.

Far from representing a powerful avant-garde leading the way to political change, the politicized class of professors is a serious political liability to any party that it supports. The hierarchical structure of academe, and the role it plays in class stratification, clings to every professor's political pronouncement like a revolting odor.

My guess is that the successful Democrats of the future will seek to distance themselves as far as possible from the bespoke jargon and pedantic tone that has constituted the professoriate's signal contribution to Democratic politics. Nothing would so efficiently invalidate conservative views with working-class Americans than if every elite college professor was replaced by a double who conceived of their work in terms of activism for right-wing ideas. Professors are bad at politics, and politicized professors are bad for their own politics….

The piece offers many other arguments as well; again, much worth reading in its entirety.

The post "Far from Representing a Powerful Avant-Garde Leading the Way to Political Change, … appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Part XIV: The Right To Keep And Bear Arms

District of Columbia v. Heller (2008)

District of Columbia v. Heller (2008)  McDonald v. City of Chicago (2010)

McDonald v. City of Chicago (2010)  New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen (2022)

New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen (2022) The post Part XIV: The Right To Keep And Bear Arms appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: November 21, 1926

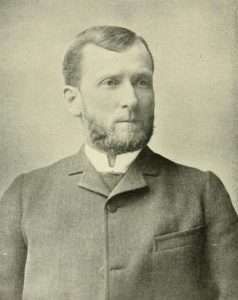

11/21/1926: Justice Joseph McKenna died.

Justice Joseph McKenna

Justice Joseph McKennaThe post Today in Supreme Court History: November 21, 1926 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Thursday Open Thread

The post Thursday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

November 20, 2024

[Josh Blackman] That Time Solicitor General Fried Redacted The Word "Plenary" From a Printed SCOTUS Reply Brief With A Marker

Attorney General Meese is a living legend. At the age of 92, he has made more contributions to the law than just about any American who did not serve on the Supreme Court. I barely scratched the surface of his remarkable career in my 2022 Meese Lecture. Yet, if you ever meet Mr. Meese (and do not call him General!), you will find a humble and sincere man. Meese is not one to boast about his voluminous accomplishments. Fortunately, two of Meese's close associates in the Reagan Administration have put pen to paper, and recorded for posterity the Attorney General's accomplishments.

Steve Calabresi and Gary Lawson have published a new book, titled The Meese Revolution: The Making of a Constitutional Moment. The book tells the story of how Meese revolutionized constitutional law in the Department of Justice, and set the stage for the current originalist majority on the Court. I would highly commend this amazing book, which was released today. (I was able to get a signed copy at the Federalist Society convention last week!)

Beyond the thorough treatment of Meese's legacy, the book has countless fun tidbits that I enjoyed. One of them concerned the case of Hodel v. Irving (1986). The book describes how Solicitor General Charles Fried had to fight the "deep state" within the SG's Office. This case presented the question of how broad the government's taking power was. Gary Lawson, who worked in OLC, favored a more narrow reading of the taking power. But the career lawyers in the SG's office used a far more capacious term: plenary.

In the early draft brief for Hodel v. Irving, the case involving the Native American lands, Lawson was surprised to see an argument—apparently authored by career SG lawyers Ed Kneedler and Larry Wallace—saying, "Moreover, every sovereign possesses the plenary power to regulate the manner and terms upon which property may be transmitted at death, as well as the authority to prescribe who shall and who shall not be capable of taking it" (emphasis added). Much of this statement was uncontroversial. No one doubts that governments can regulate the passage of property by will; there have long been statutes defining how to write a valid will, limiting to some extent the power fully to disinherit certain family members, and so forth. The key to the draft brief's argument was the word "plenary."

However, the political appointees in DOJ objected to the word "plenary":

In the early draft brief for Hodel v. Irving, the case involving the Native American lands, Lawson was surprised to see an argument—apparently authored by career SG lawyers Ed Kneedler and Larry Wallace—saying, "Moreover, every sovereign possesses the plenary power to regulate the manner and terms upon which property may be transmitted at death, as well as the authority to prescribe who shall and who shall not be capable of taking it" (emphasis added). Much of this statement was uncontroversial. No one doubts that governments can regulate the passage of property by will; there have long been statutes defining how to write a valid will, limiting to some extent the power fully to disinherit certain family members, and so forth. The key to the draft brief's argument was the word "plenary."

So what did Fried do? He pulled out a marker and redacted the word "plenary" from the brief:

Recall how Fried mentioned that he sometimes received briefs from his staff with little or no time to make revisions. This time, he received printed copies of the brief—several dozen of them—ready to be filed with the Supreme Court. The brief described the government's "plenary" power over testation, including its ability to abolish altogether people's power to pass down their property. There was then no way to make revisions to the briefs; they were in final printed form. Charles Fried found a way. On the eve (literally the eve) of filing the briefs in the Supreme Court, he took a marker and personally, by hand, blacked out the word "plenary" in every printed copy of the brief. Today, when everything is digitized, this remarkable event is in danger of disappearing. But if one can locate a hard copy of the brief (there are nine depositories for printed SG briefs across the country), or a PDF that accurately reproduces the original document, one will see a handmade deletion in every copy. This was Charles Fried at his finest—and the career staff in the SG's Office doing what it did.

When I read this passage, I immediately emailed the amazing librarians at the South Texas College of Law to find the brief. Fortunately, they have microfiched copies of Supreme Court briefs from the 1980s. And they found the Hodel reply brief:

On page 5 of the brief, you can see the redaction:

And the marker bled through to page 6:

If you pull up the brief on Westlaw, there are two question marks in the place of the redaction

The story gets even better. Justice O'Connor asked Ed Kneedler about this issue during oral argument:

The story gets even better. Justice O'Connor asked Ed Kneedler about this issue during oral argument:

There is a coda to the story. Even after Fried's heroic effort at damage control, if one held up the marked-out portion of the printed briefs to the light, one could faintly see the word "plenary" underneath. At oral argument in Hodel v. Irving, when Ed Kneedler presented the government's case, Justice O'Connor asked, "Mr. Kneedler, are there any limits in your view as to what the government can do or change concerning the descent of property belonging to Indians? Do you think the government has plenary power to really make any kind of a regulation?" (Lawson was in the gallery during this argument and had to choke back laughter when Justice O'Connor varied her typically polite and soothing tone to give pointed emphasis to the word "plenary.") Kneedler replied, no doubt as he had been ordered to reply, "No, our submission does not go nearly that far." He then added, however, that "[t]he Court has described the power of the legislature over the descent of property in very broad terms, suggesting that the right to pass property and to receive it by descent or by will is creation of statute and not a natural right, it is a privilege that can be conditioned or even abolished, but the Court has never been confronted with a situation where it had to address that, and it isn't here." A simple "no," of course, would have sufficed, but Kneedler insisted on emphasizing at least the possibility that governments could abolish the transfer of property at death. Justice O'Connor followed up: "Well, do you take the position that it can be abolished?" Kneedler responded, "That is not part of our submission here, no," and sought to explain the limited scope of the law actually at issue in the case.

An amazing story, from an amazing book.

The post That Time Solicitor General Fried Redacted The Word "Plenary" From a Printed SCOTUS Reply Brief With A Marker appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Federal Courts Still Lack Authority to Issue Advisory Opinions

It is not often that federal court opinion begins by referencing the Judiciary Act of 1789, but sometimes it is called for.

Earlier this month, Judge Eric Murphy of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit wrote a short gem of an opinion in Bowles v. Whitmer reminding us all (including the litigants before him) that federal courts lack the authority to issue advisory opinions.

His opinion for a unanimous panel begins:

The Judiciary Act of 1789 required Justices of the Supreme Court to "ride circuit" by traveling great distances to resolve cases on the new circuit courts. See Pub. L. No. 1-20, § 4, 1 Stat. 73, 74–75. Losing litigants could then appeal their decisions to the Supreme Court. See id. § 13, 1 Stat. at 81. Some Justices raised "constitutional and practical" objections to this circuit-riding duty. David P. Currie, The Constitution in Congress: The Federalist Period 54 (1997). Worried about appearances of bias if the full Court affirmed a colleague, they wrote to President Washington that observers might think "mutual interest" on the Court "had generated mutual civilities and tendernesses injurious to right." 3 Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States § 1573, at 440 n.1 (1833). But the Court later upheld the constitutionality of circuit riding, reasoning that the practice's continuation for a decade had "fixed" the Constitution's "construction." Stuart v. Laird, 5 U.S. 299, 309 (1803).

The plaintiffs in this case seek to reopen this debate. Michigan's legislature has waived the State's sovereign immunity by creating a specialized court, the Court of Claims, in which plaintiffs may sue the State. The Court of Claims now consists of judges from the Michigan Court of Appeals. So when parties appeal judgments of the Court of Claims, other appellate judges on the Court of Appeals review their colleagues' decisions. According to the plaintiffs, this practice violates the Fourteenth Amendment. Our resolution of their challenge must start with a different letter that the Justices wrote to President Washington. When he asked for their legal guidance on a foreign-affairs matter, they responded that they could "not issue advisory opinions" outside an actual case. See FDA v. All. for Hippocratic Med., 602 U.S. 367, 378–79 (2024) (citing 13 Papers of George Washington: Presidential Series 392 (Christine Sternberg Patrick ed. 2007)). Because the plaintiffs here seek such an opinion about the constitutionality of the Court of Claims, we agree with the district court that they lack Article III standing. We affirm.

The post Federal Courts Still Lack Authority to Issue Advisory Opinions appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Part XIII: No Law Respecting An Establishment Of Religion

Engel v. Vitale (1962) Governmental Purpose to Advance Religion

Engel v. Vitale (1962) Governmental Purpose to Advance Religion  McCreary County, Kentucky v. ACLU of Kentucky (2005)

McCreary County, Kentucky v. ACLU of Kentucky (2005)  Van Orden v. Perry (2005)

Van Orden v. Perry (2005)  Town of Greece v. Galloway (2014)

Town of Greece v. Galloway (2014)  American Legion v. American Humanist Association (2019)

American Legion v. American Humanist Association (2019) The post Part XIII: No Law Respecting An Establishment Of Religion appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers