Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 220

November 25, 2024

[Eugene Volokh] Testimony About Snapchat Messages Not Precluded by "Best Evidence" Rule

From Turner v. State, decided Thursday by the Arkansas Supreme Court (in an opinion by Justice Shawn Womack):

The evidence presented at trial establishes the following account of events. On April 26, 2021, Shelby and Verser were sitting in a parked car after returning from dinner when they were ambushed by three gunmen. In a matter of seconds, twenty-three bullets were fired into the vehicle, striking Shelby and Verser repeatedly, killing both. Shelby, age twenty, and Verser, age twenty-three, were killed instantly. Turner, a close acquaintance of Shelby's, was implicated in facilitating the ambush. Testimony and phone records from the night showed that Turner had communicated with the gunmen multiple times just before the shooting, despite later denying that he knew them. These communications—coupled with security footage and witness testimony—presented Turner as the primary organizer of the murders….

After the shooting, Turner attempted to conceal his involvement…. [Among other things, a] key witness, … Pavliv[,] testified that after she informed Turner of police questioning, he sent a Snapchat message instructing her to withhold information about the gun….

Turner contends that the circuit court abused its discretion in allowing testimony from Pavliv about a self-destructing Snapchat message that Turner sent her in violation of Arkansas Rule of Evidence 1002. Specifically, Turner contends that admitting this testimony violated the best-evidence rule because the message itself was not produced. However, the State disputes the rule's applicability, given that Snapchat messages are designed to be deleted automatically. Testimony from Pavliv established that Snapchat messages self-destruct and were unavailable for retrieval, much like a telephone conversation, which does not produce a permanent record. Thus, the State claims the general exception to the best-evidence rule, Arkansas Rule of Evidence 1004, is implicated….

The "best evidence" rule provides, in relevant part, that "[t]o prove the content of a writing, recording, or photograph, the original writing, recording, or photograph is required," but not if:

(1) Originals Lost or Destroyed. All originals are lost or have been destroyed, unless the proponent lost or destroyed them in bad faith;

(2) Original Not Obtainable. No original can be obtained by any available judicial process or procedure;

(3) Original in Possession of Opponent. At a time when an original was under the control of the party against whom offered, he was put on notice, by the pleadings or otherwise, that the contents would be a subject of proof at the hearing; and he does not produce the original at the hearing; or

(4) Collateral Matters. The writing, recording or photograph is not closely related to a controlling issue.

And exception (1), the court held, applied here:

The best-evidence rule applies only if an "original" exists, but Pavliv's testimony established that the Snapchat communication, as was customary, was automatically deleted. In such instances, Rule 1004 of the Arkansas Rules of Evidence permits other evidence of the message's contents when the original is lost or destroyed without bad faith. Because Rule 1004 clearly applies here, the circuit court acted within its discretion in admitting Pavliv's testimony under this exception.

Turner further argues that the State was required to attempt retrieval of the Snapchat message, yet Rule 1004 does not impose this requirement. Indeed, Rule 1004's provisions are disjunctive; it is enough that the message was lost without bad faith, which was supported by Pavliv's testimony. It should also be noted that courts in other jurisdictions have found that the self-destructing nature of Snapchat messages leaves witness testimony as the sole admissible evidence in such cases, reinforcing the circuit court's decision here….

David L. Eanes Jr. represents the state.

The post Testimony About Snapchat Messages Not Precluded by "Best Evidence" Rule appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] New Article on "Birthright Citizenship and Undocumented Immigrants"

At the Just Security site, I have a new article explaining why the incoming Trump administration's apparent plan to deny birthright citizenship to US-born children of undocumented immigrants is unconstitutional:

The incoming Trump administration may be preparing to deny citizenship rights to children of undocumented immigrants born in the United States… According to the New York Times, "the team plans to stop issuing citizenship-affirming documents, like passports and Social Security cards, to infants born on domestic soil to undocumented migrant parents in a bid to end birthright citizenship."

Such policies would be a blatant violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, both the text and the original meaning. Section 1 of the Amendment grants citizenship to anyone "born … in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof." There is no exception for children of illegal migrants. There is broad agreement on that point among most constitutional law scholars, across the ideological and methodological spectrum….

In the article, I also criticize various arguments to the effect that children of undocumented immigrants are not covered because illegal migrants are not within the "jurisdiction" of the United States. That includes both traditional claims that "jurisdiction" only covers people who have the same rights as citizens (an argument that would destroy the entire purpose of the Citizenship Clause), and newer arguments claiming that undocumented migrants aren't covered because they are "invaders."

The post New Article on "Birthright Citizenship and Undocumented Immigrants" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Thanksgiving Food Tips?

What's a tasty, unusual, Thanksgiving-compatible dish you've had at Thanksgiving? If you have some you can recommend, please describe them in the comments (and add a link to a recipe if you have one). Naturally, tasty and unusual twists on standard dishes would count.

The post Thanksgiving Food Tips? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Must Government Pay Compensation When It Damages Innocent Owner's Property in Police Action?

From Justice Sotomayor's opinion today respecting denial of certiorari in Baker v. City of McKinney, joined by Justice Gorsuch:

The Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment provides that private property shall not "be taken for public use, without just compensation." This case raises an important question that has divided the courts of appeals: whether the Takings Clause requires compensation when the government damages private property pursuant to its police power.

On July 25, 2020, in McKinney, Texas, a fugitive named Wesley Little kidnapped a 15-year-old girl. After evading the police in a high-speed car chase, Little found his way to petitioner Vicki Baker's home with his victim in tow. Little was familiar with the home because he had previously worked there as a handyman. Baker had recently retired and moved to Montana, so her daughter Deanna Cook was at the house that day, preparing to put it up for sale. When Cook answered the door, she recognized Little and the child with him: Earlier that day, Cook saw on Facebook that Little was on the run with a teenage girl. Cook feigned ignorance and let them into the house, but told Little, falsely, that she had to go to the supermarket. Once outside, Cook called Baker, who called the police.

McKinney police arrived soon after and set up a perimeter around Baker's home. Eventually, Little released the girl and she exited the house. The girl told the police that Little was hiding in the attic, that he was armed, and that he was high on methamphetamine. Later, while still in the attic, Little told the police that he was not going back to prison, that he knew he was going to die, and that he planned to shoot it out with the police.

To resolve the standoff and protect the surrounding community, the police tried to draw Little out by launching dozens of tear gas grenades into the home. When that did not work, the officers detonated explosives to break down the front and garage doors and used a tank-like vehicle to bulldoze the home's backyard fence. By the time the officers gained entry, Little had taken his own life. All agree that the McKinney police acted properly that day and that their actions were necessary to prevent harm to themselves and the public.

The actions of the police also caused extensive damage to Baker's home and personal belongings, however. As the District Court explained:

"'The explosions left Baker's dog permanently blind and deaf. The toxic gas that permeated the House required the services of a HAZMAT remediation team. Appliances and fabrics were irreparable. Ceiling fans, plumbing, floors (hard surfaces as well as carpet), and bricks needed to be replaced—in addition to the windows, blinds, fence, front door, and garage door. Essentially all of the personal property in the House was destroyed, including an antique doll collection left to Baker by her mother.'"

In total, the damage amounted to approximately $50,000. Baker's insurance refused to cover any damage caused by the McKinney police. {Homeowners' insurance policies generally do not provide coverage for damage caused by the government.} Baker, who bore no responsibility for what had occurred at her home, then filed a claim for property damage with the city. The city denied the claim in its entirety….

[The Fifth Circuit below] declined to adopt the city's broad assertion that the Takings Clause never requires compensation when a government agent destroys property pursuant to its police power. Such a broad categorical rule, the Fifth Circuit reasoned, was at odds with its own precedent and this Court's Takings Clause jurisprudence.

Instead, the Fifth Circuit adopted a narrower rule that it understood to be compelled by history and precedent: The Takings Clause does not require compensation for damaged property when it was "objectively necessary" for officers to damage the property in an active emergency to prevent imminent harm to persons. Because the parties agreed that the McKinney police's actions were objectively necessary, the Fifth Circuit concluded that Baker was not entitled to compensation. Baker now petitions for certiorari and asks this Court to reverse the Fifth Circuit's judgment.

The Court's denial of certiorari expresses no view on the merits of the decision below. I write separately to emphasize that petitioner raises a serious question: whether the Takings Clause permits the government to destroy private property without paying just compensation, as long as the government had no choice but to do so. Had McKinney razed Baker's home to build a public park, Baker undoubtedly would be entitled to compensation. Here, the McKinney police destroyed Baker's home for a different public benefit: to protect local residents and themselves from an armed and dangerous individual. Under the Fifth Circuit's decision, Baker alone must bear the cost of that public benefit.

The text of the Takings Clause states that private property may not "be taken for public use, without just compensation." The Takings Clause was "designed to bar Government from forcing some people alone to bear public burdens which, in all fairness and justice, should be borne by the public as a whole." This Court has yet to squarely address whether the government can, pursuant to its police power, require some individuals to bear such a public burden.

This Court's precedents suggest that there may be, at a minimum, a necessity exception to the Takings Clause when the destruction of property is inevitable. Consider Bowditch v. Boston (1879), in which the Court held that a building owner was not entitled to compensation after firefighters destroyed his building to stop a fire from spreading…. "At the common law every one had the right to destroy real and personal property, in cases of actual necessity, to prevent the spreading of a fire, and there was no responsibility on the part of such destroyer, and no remedy for the owner" …. Bowditch interpreted Massachusetts state law, but subsequent cases have relied on Bowditch in the Takings Clause context.

Similarly, in United States v. Caltex (Philippines), Inc. (1952), this Court held that the Takings Clause did not require the Government to pay compensation for its destruction of oil companies' terminal facilities amid a military invasion. The destruction of that property during wartime was necessary, the Court explained, "to prevent the enemy from realizing any strategic value from an area which he was soon to capture."

That holding accorded with the common-law principle "that in times of imminent peril—such as when fire threatened a whole community—the sovereign could, with immunity, destroy the property of a few that the property of many and the lives of many more could be saved." These cases do not resolve Baker's claim, however, because the destruction of her property was necessary, but not inevitable. Whether the inevitable-destruction cases should extend to this distinct context remains an open question….

The post Must Government Pay Compensation When It Damages Innocent Owner's Property in Police Action? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Monday Open Thread

The post Monday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

November 24, 2024

[Jonathan H. Adler] DC Circuit Finds Some FINRA Authority Violates Private Nondelegation Doctrine

On Friday–the same day the Supreme Court granted certiorari in a case raising the private nondelegation doctrine–the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit concluded that at least some of the authority wielded by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), without adequate federal oversight, violates the private nondelegation doctrine.

Judge Millett wrote the 41-page opinion for the panel in Alpine Securities Corp. v. FINRA, joined by Chief Judge Srinivasan. Judge Walker concurred in the judgment in part and dissented in part, as he would have looked favorably on more of the challenge to FINRA than the majority.

Judge Millett summarized the case and the court's conclusions as follows:

The United States securities industry is regulated by both private entities and the federal government. These private regulators, referred to as self-regulatory organizations, date back centuries to when groups of securities traders adopted self-governing rules by which they would conduct business and ensure public trust in their operations.

Today, a private corporation, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority ("FINRA"), regulates and oversees large parts of the securities industry. Congress, however, has overlain federal law on those private self-regulatory practices. As relevant here, federal law effectively requires most firms and individuals that trade securities to join FINRA as a condition of engaging in that business. Federal law, in turn, subjects FINRA to oversight by the Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC") and requires that FINRA ensure that its members comply both with FINRA's own rules and with federal securities laws.

In 2022, FINRA sanctioned one of its members, Alpine Securities Corporation, for violating FINRA's private rules for member behavior and imposed a cease-and-desist order against Alpine. Alpine then sued in federal court, challenging FINRA's constitutionality.

While that lawsuit was pending, FINRA concluded that Alpine had violated the cease-and-desist order and initiated an expedited proceeding to expel Alpine from membership in FINRA. Alpine then sought a preliminary injunction from the district court against the expedited proceeding, arguing that FINRA is unconstitutional because its expedited action against Alpine violates either the private nondelegation doctrine or the Appointments Clause. The district court denied the preliminary injunction.

We now reverse only to the extent the district court allowed FINRA to expel Alpine with no opportunity for SEC review. Alpine is entitled to that limited preliminary injunction because it has demonstrated that it faces irreparable harm if expelled from FINRA and the entire securities industry before the SEC reviews the merits of FINRA's decision. Alpine has also demonstrated a likelihood of success on its argument that the lack of governmental review prior to expulsion violates the private nondelegation doctrine. We accordingly hold that FINRA may not expel Alpine either before Alpine has obtained full review by the SEC of the merits of any expulsion decision or before the period for Alpine to seek such review has elapsed.

At the same time, we hold that Alpine has not demonstrated that it will suffer irreparable harm from participating in the expedited proceeding itself as long as FINRA cannot expel Alpine until after the SEC conducts its own review. For that reason, Alpine has not shown that it is entitled to a preliminary injunction halting that proceeding altogether.

As this case comes to us in a preliminary-injunction posture, we necessarily do not resolve the ultimate merits of any of Alpine's constitutional challenges, and our determination about Alpine's likelihood of success on the private nondelegation issue is based only on the early record in this case. We leave it to the district court on remand to determine the ultimate merits of Alpine's claims.

Judge Walker's 29-page opinion concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting in part begins:

Article II of the Constitution begins, "The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America." That means private citizens cannot wield significant executive authority. Nor can anyone in the government, except for the President and the executive officers appointed and removable consistent with Article II.

The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority is a nominally private corporation. It investigates, prosecutes, and adjudicates violations of federal securities laws. Those laws generally forbid broker-dealers from doing business unless they belong to FINRA.

Today, the majority holds that the Constitution likely requires government review before FINRA may expel a company from its ranks and thereby put that company out of business. That holding is a victory for the Constitution.

But it is only a partial victory because the problems with FINRA's enforcement proceedings run even deeper. FINRA wields significant executive authority when it investigates, prosecutes, and initially adjudicates allegations against a company required by law to put itself at FINRA's mercy. That type of executive power can be exercised only by the President (accountable to the nation) and his executive officers

(accountable to him).By flouting that principle through an "illegitimate proceeding, led by an illegitimate decisionmaker," FINRA imposes an irreparable injury that this court should prevent by granting the requested preliminary injunction in its entirety.

I respectfully dissent from the majority's decision to deny that relief.

I am quite sure Alpine Securities will file a petition for certiorari. The question is whether FINRA will do the same (or whether it will file a petition for rehearing en banc).

The post DC Circuit Finds Some FINRA Authority Violates Private Nondelegation Doctrine appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: November 24, 2001

11/24/2001: Salim Hamdan was captured in Afghanistan. The Supreme Court would decide his case in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006).

The Roberts Court (2006)

The Roberts Court (2006)The post Today in Supreme Court History: November 24, 2001 appeared first on Reason.com.

November 23, 2024

[Eugene Volokh] Our New Threads Account Is at https://www.threads.net/@volokhconspi...

We used to have our Threads at @volokhc, but we lost access to the underlying Instagram page and therefore the Threads account.

It's possible that the problem was that I listed the name as "Volokh Conspiracy" and then changed it to "Eugene Volokh (Volokh Conspiracy)," and perhaps Instagram insisted that the name be just "Eugene Volokh." But the error messages were never clear; I was told several times that the account had been reinstated, only to have it flagged again; I was asked for photo id's and provided them but was told they couldn't be read; and I wasn't able to change the user name to "Eugene Volokh," if that was the thing I needed to do.

If anyone can help explain how I can recover the @volokhc page, and change the name, if necessary, I'd appreciate that. But fortunately we only had about 20-odd followers there (compared to >600 on Bluesky, in roughly the same length of time), so I hope the change won't trouble too many people. If you are one of our Threads @volokhc followers, please just shift to @volokhconspiracy. (Our Twitter, Mastodon, and Bluesky feeds remain @volokhc.)

The post Our New Threads Account Is at https://www.threads.net/@volokhconspiracy appeared first on Reason.com.

[Orin S. Kerr] Why Do Search Warrants "Command" that Searches Occur?

If you read a lot of search warrants, you may have noticed something odd about the standard search warrant form. Search warrants command the officer to conduct the search. They don't just authorize the search. Instead they order the officer to conduct the search. The warrant language is mandatory, not permissive.

Consider the federal warrant form. It not only commands the execution of the search, but it puts the command in allcaps and bold: "YOU ARE COMMANDED to execute this warrant . . ." State warrants are written in the same basic way. And authorizing statutes on issuing warrants usually have that language, too.

If you think about it, that's pretty weird. After all, it's the officer who applied for the warrant. The officer is seeking permission to conduct the search, so it's a little strange to order the officer to do what the officer has asked for permission to do.

Plus, despite what the warrant form says, executing the warrant is not really mandatory. If the officer doesn't execute the warrant, that's not a problem. The court can just reissue the warrant if the agents later decide to search, or not if they don't. See, e.g., State v. Nunez, 67 P.3d 831 (Idaho 2003) (holding that, where officers did not execute a warrant during the period it was active and later sought a new warrant, the magistrate judge can just reissue the old warrant on the same piece of paper and it becomes a new warrant).

And sometimes the law doesn't even allow the officer to execute the warrant. If probable cause is lost after the warrant is obtained but before the warrant is executed, the officer can't do what the warrant says he is required to do. See United States v. Spencer, 530 F.3d 1003 (D.C. Cir. 2008) (Kavanaugh, J.) ("[W]hen officers learn of new facts that negate probable cause, they may not rely on an earlier-issued warrant but instead must return to the magistrate—for example, if the police learn that contraband is no longer located at the place to be searched.").

What gives? What explains the mandatory language that gets treated as permissive language in practice?

The answer, I think, is history.

Here's the relevant picture, at least as I understand it. At common law, the basic apparatus of government law enforcement that we know today did not exist. Police as we know it hadn't been invented yet. Victims of crime were mostly on their own. They had to investigate crimes themselves. And they had to bring prosecutions, too. Very few criminal cases were brought by the government. Rather, victims of crimes had to serve as the prosecutors. It was a regime of private enforcement of public rights. See generally J.M. Beattie, Crime and the Courts in England, 1660-1800.

This doesn't mean there was no state at all. Constables were around, and one of their jobs was helping people out with carrying out arrests and (in rare cases) executing search warrants. But there wasn't much of an incentive for constables to do this. One important role of the law of criminal procedure in that era was creating incentives for constables to do their jobs. Here's what I wrote on this back in 2019, focusing on arrests—although the same was true for searches:

The part-time officials such as constables (and I'll just call them all constables for the sake of brevity) didn't have much interest in making arrests and detaining people after the arrest. It was dangerous and time-consuming work, and they in general weren't paid for it. Who wants to risk getting hurt arresting someone and forcibly bringing him to the local judge? There's not nothing in it for the constable. So part of the law regulating constables at common law was about forcing the constables to do their jobs—to make arrests and to detain prisoners—or else face civil suits or criminal punishment.

The law regulating constables had two features relevant here. First, the constable was required to at least try to execute the warrant. A constable who declined to do it could be charged with a crime or sued for neglect of duty.

And second, a constable who made an arrest but then let the prisoner go could be charged with the crime of escape (see 590-95) or sued in tort under the tort of escape. A constable was liable for escape when he made an arrest but then the prisoner went free, either because the constable intentionally let the prisoner go (called "voluntary escape") or the prisoner escaped despite the constable's efforts to detain him (called "negligent escape").

From this perspective, the idea that a search warrant would order the constable to execute it makes a lot of sense. In those days, search warrants were obtained mostly to recover stolen goods. The property owner who had their stuff stolen would figure out where their stuff had been taken, and they would go to the local Justice of the Peace and seek a search warrant to search that place and bring their stuff back. The applicant for the warrant was the victim, and he needed the constable to execute the warrant for him—something the constable may have had no interest in doing.

In that world, a search warrant needed to do more than authorize a search. It had to order the constable to execute the search on the victim-complainant's behalf.

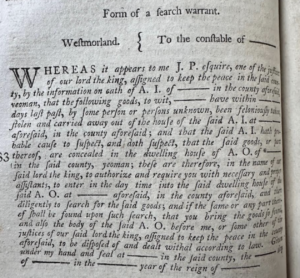

Consider the sample form search warrant that appeared in the influential Justice of the Peace manual, Richard Burns, The Justice of the Peace, And Parish Officer (1793 ed.):

Here, the warrant is being sought to recover stolen goods belonging to the victim, A.I. The victim, A.I., has provided the basis of probable cause. The victim, A.I,, has probable cause to believe that someone stole his stuff and that his stuff is now hidden in A.O.'s house. The warrant is addressed to the constable, and it does "authorize and require" the constable, "with necessary and proper assistants," to break into A.O.'s house and to search A.O.'s house for A.I.'s stolen goods—and if A.I.'s things are found, to retrieve them and (if he's there) to arrest A.O. and to bring them to the Justice of the Peace. The warrant is being sought by the victim, and the warrant is addressed to the constable as an order.

Incidentally, I think this also explains why warrants name the officer—or group of officers—who is required to execute the search. That previously struck me as odd. After all, if the warrant is merely an authorization to search, who cares which specific officer executes it? Some government agent can do it; that's all that should matter, right? But at common law, who executes the warrant was important. In an era when the warrant was commanding the constable to do something the constable probably didn't want to do, it was presumably important for the warrant to state exactly who had the responsibility to do what the court was commanding.

If I'm right, the answer to this puzzle is simple: the world changed, but no one updated the form.

The post Why Do Search Warrants "Command" that Searches Occur? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Supreme Court Grants Certiorari in Nondelegation Case

Yesterday, as predicted, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in Federal Communications Commission v. Consumers' Research (consolidated with ). This case arises out of challenges to the constitutionality of the FCC's Universal Service Fee, and may produce a major administrative law decision–but the Court also gave itself an out.

As I noted here, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, sitting en banc, concluded that the fee is unconstitutional. By a vote of 9-7, the court concluded that this fee is, in effect, a tax, and that insofar as the level of the fee is set by a private entity (the Universal Service Administrative Company), this violates the nondelegation doctrine.

As is nearly always the case when a federal court concludes a federal statute is unconstitutional, the Solicitor General filed for certiorari, and certiorari was granted. Here, the SG's petition posed three questions:

In 47 U.S.C. 254, Congress required the Federal Communications Commission (Commission) to operate universal service subsidy programs using mandatory contributions from telecommunications carriers. The Commission has appointed a private company as the programs' Administrator, authorizing that company to

perform administrative tasks such as sending out bills, collecting contributions, and disbursing funds to beneficiaries. The questions presented are as follows:1. Whether Congress violated the nondelegation doctrine by authorizing the Commission to determine, within the limits set forth in Section 254, the amount that providers must contribute to the Fund.

2. Whether the Commission violated the nondelegation doctrine by using the Administrator's financial projections in computing universal service contribution rates.

3. Whether the combination of Congress's conferral of authority on the Commission and the Commission's delegation of administrative responsibilities to the Administrator violates the nondelegation doctrine.

Note that this case both presents traditional nondelegation questions–whether there are limits on Congress' power to delegate authority to a federal agency–but also what is referred to as the "private nondelegation doctrine." This latter doctrine concerns whether there are distinct limits on the ability of Congress to delegate (or authorize the delegation of) power to private entities. Concluding there are limits to the delegation of power to private entities (or limits on the ability of agencies to subdelegate such power) does not require concluding that the nondelegation doctrine itself has much force. In other words, the Court could conclude that the method of determining or imposing the Universal Service Fee is unconstitutional without overturning or tightening the "intelligible principle" standard reaffirmed in Whitman v. American Trucking Associations.

But it is also possible that the Court will not even reach the nondelegation question. In granting the SG's petition, the Court added an additional question to the case. From the order:

In addition to the questions presented by the petitions, the parties are directed to brief and argue the following question: Whether this case is moot in light of the challengers' failure to seek preliminary relief before the Fifth Circuit.

Concluding the case is moot would enable the Court to avoid the merits question. It is also an interesting addition to the case as this is one of several cases in which the Court is (in effect) considering whether some lower courts have been too permissive in hearing challenges to agency actions. This is something of a theme in this term's administrative law cases and will be worth watching.

The post Supreme Court Grants Certiorari in Nondelegation Case appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers