Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 208

December 12, 2024

[David Kopel] Firearms Law Works-in-Progress Conference 2025

This June, the University of Wyoming Firearms Research Center and the Duke Center for Firearms Law will host their seventh annual joint Works-in-Progress Conference. These two Centers are the only firearms law/policy centers in the United States that are open to and that publish papers from diverse viewpoints. I am a Senior Fellow at the Wyoming Center

If your paper is accepted for the Wyoming/Duke Conference, you are of course free to eventually publish it in any journal you want; however, there is an expectation that you will write a summary of the paper for publication on the blogs of the Wyoming and Duke Centers.

To present a paper, you do not need to be a professor. Past conferences have included, from example, some fine presentations from practicing lawyers. (Or muggles, as law professors secretly call them.)

The conference is also an excellent opportunity for friendly interactions with scholars from other disciplines, and with diverse viewpoints on arms issues. At last year's conference, Minnesota Law prof. Megan Walsh publicly humiliated me by presenting me in a Minnesota Timberwolves jersey, to commemorate Minnesota's defeat of the reigning champion Denver Nuggets in the NBA Conference semifinals, including a 115-70 obliteration in game 6.

Below is the call for papers:

DATE: June 5-6, 2025

LOCATION: Laramie, WY

ABSTRACTS DUE: February 17, 2025

The University of Wyoming Firearms Research Center and the Duke Center for Firearms Law invite applications to participate in the seventh annual Firearms Law Works-in-Progress Conference. The conference will be held at the University of Wyoming College of Law in Laramie, Wyoming, on June 5 & 6, 2025. We ask all those interested in presenting a paper at the conference to submit an abstract by February 17, 2025.

At the Firearms WIP Conference, scholars and practitioners present and discuss works-in-progress related to firearms law and policy broadly defined, including Second Amendment history and doctrine, federal and state gun regulation, and the intersection between firearms law and other areas of law. The Firearms WIP Conference is the only legal works-in-progress event specifically focused on firearms law and policy. Summaries of past conferences, including paper titles and attendees, are available here: 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024.

Conference sessions are lively discussions among authors, discussants, and participants. Each accepted paper is assigned to a panel of three to four scholars with a moderator who will summarize the papers and then lead a discussion. Sessions run from Thursday afternoon through Friday afternoon. There will be a casual dinner and social event Thursday evening following the afternoon session. All conference participants are expected to read the papers in advance and to attend the entire conference.

We accept papers on a wide array of topics related to firearms, including from scholars who are new to the field and interested in exploring the interaction between firearms law and other disciplines. Although participation at the conference is by invitation only, we welcome paper proposals from scholars and practitioners all over the world. Please feel free to share this call for submissions widely.

Submission Details

Titles and abstracts of papers should be submitted electronically to frc@uwyo.edu no later than February 17, 2025. Abstracts should be no longer than one page, and should be submitted as a PDF file saved under the file name "[last name, first name] – [paper title]." Please use the subject line "WIP Paper Submission" in your email. Authors will be informed whether their paper has been accepted no later than March 10, 2025. Workshop versions of accepted papers will be due in mid-May, so that they can be circulated to moderators and other conference participants in advance of the conference.We expect that participants' home institutions will cover travel expenses to the extent possible. However, the Wyoming FRC and Duke CFL are able to cover some costs of lodging and travel expenses for authors who would not otherwise be able to attend. This support is intended to encourage submissions from junior faculty, especially those who are new to the field.

The post Firearms Law Works-in-Progress Conference 2025 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Silencers Aren't "Arms" Protected by Second Amendment, Fourth Circuit Holds

From U.S. v. Saleem, decided today by Judges J. Harvie Wilkinson, Steven Agee, and Allison Rushing:

The Supreme Court in Heller defined "arms" as "any thing that a man wears for his defence, or takes into his hands, or useth in wrath to cast at or strike another." Therefore, "the Second Amendment extends … to all instruments that constitute bearable arms, even those that were not in existence at the time of the founding." While a silencer may be a firearm accessory, it is not a "bearable arm" that is capable of casting a bullet.

Moreover, while silencers may serve a safety purpose to dampen sounds and protect the hearing of a firearm user or nearby bystanders, it fails to serve a core purpose in the arm's function. A firearm will still be useful and functional without a silencer attached, and a silencer is not a key item for the arm's upkeep and use like cleaning materials and bullets. Thus, a silencer does not fall within the scope of the Second Amendment's protection.

Julia K. Wood represents the government.

The post Silencers Aren't "Arms" Protected by Second Amendment, Fourth Circuit Holds appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Congress Passes Legislation to Create Needed Judgeships, but Biden May Veto

The Judicial Conference has called for the creation of additional judgeships -- primarily district court seats in parts of the country plagued by judicial backlogs. The Federal Bar Association has joined the call for more judgeships, and endorsed the JUDGES Act, which would authorize 66 new district court judgeships over the next decade, staggered so as to spread the nominations across presidential administrations.

The Senate passed the JUDGES Act earlier this year, before the August recess. Some hoped it would pass before the election, when it was still unknown who would get the first opportunity to fill new seats, but that did not happen.

Earlier this week, the FBA and Federal Judges Association issued a statement urging adoption of the JUDGES Act. It reads in part:

Our federal courts observed over 30 percent growth in their caseloads since the last comprehensive judgeship legislation three decades ago and the lack of new judgeships has contributed to profound delays in the resolution of cases and serious access to justice concerns. It is the litigants and residents of the Nation who suffer when there is a delay in deciding cases, and the enactment of the JUDGES Act would have a substantial positive impact on the efficient administration of justice for all Americans.

Now, more than ever, our judicial system needs enactment of the JUDGES Act. It adds judges in a non-partisan manner and through its creative staggered approach to creating these new judgeships, offers the best chance in three decades for addressing the increasing judicial caseload crisis. Failure to enact the JUDGES Act will condemn our judicial system to more years of unnecessary delays and will deprive parties in the most impacted districts from obtaining appropriate justice and timely relief under the rule of law.

The statement is signed by FBA President Glenn McMurry and FJA President Judge Michelle Childs (a Biden appointee to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit).

Today, the House passed the JUDGES Act with bipartisan support, 236-173.

The White House, however, is threatening to veto the bill, claiming that additional judgeships are unnecessary, even though the Judicial Conference and FBA claim otherwise.

According to the National Law Journal, judges are discouraged by the White House veto threat, with one Obama appointee calling it "really deflating." From that report:

Federal judges must prioritize criminal matters, and as a result of heavy caseloads, civil cases in particular can drag on. According to the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, the number of civil cases pending more than three years rose from 18,280 to 81,617 over the last 20 years.

Chief U.S. District Judge Marcia Morales Howard of the Middle District of Florida said the court's Ocala division currently has no judges assigned there and has the busiest docket in the district.

At least six senior judges and one active judge take on the division's docket, she said. But she said many aging senior judges are beginning to roll back the number of cases they take on, which could pose a problem.

"The Middle Florida is huge. It's 35 of the 67 counties in the state. It's 60% of the population of the state," said Howard, a George W. Bush appointee. "So we desperately need these judgeships."

Howard said the bill would add five judges to the court over a decade: one in 2025, one in 2027, one in 2031, one in 2033, one in 2035.

There is no question that partisans prefer to authorize new judgeships when they know a president of their own party will get to fill the seats. That is one reason the JUDGES Act staggers vacancies over the next decade. The reality remains that more district court judgeships are needed, and it would be unfortunate if partisan concerns prevented these seats from being created.

The post Congress Passes Legislation to Create Needed Judgeships, but Biden May Veto appeared first on Reason.com.

[Orin S. Kerr] Kindle Version of "The Digital Fourth Amendment" Is Now Available

I'm very pleased to say that the Kindle version of my new book, The Digital Fourth Amendment: Privacy and Policing in Our Online World, is now available for sale. The print version comes out January 10th, but the electronic version is out today.

This is the first regular-audience book I have written—it's about law, but I've targeted it for general audiences in addition to lawyers and other law types—and here's the dust-jacket blurb:

When can the government read your email or monitor your web surfing? When can the police search your phone or copy your computer files? In the United States, the answers come from the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution and its ban on 'unreasonable searches and seizures.'

The Digital Fourth Amendment: Privacy and Policing in Our Online World takes the reader inside the legal world of how courts are interpreting the Fourth Amendment in the digital age. Computers, smartphones, and the Internet have transformed criminal investigations, and even a routine crime is likely to lead to digital evidence. But courts are struggling to apply old Fourth Amendment concepts to the new digital world. Mechanically applying old rules from physical investigations doesn't make sense, as it often leads to dramatic expansions of government power just based on coincidences of computer design.

Written by a prominent law professor whose scholarship has often been relied on by courts in the field, The Digital Fourth Amendment shows how judges must craft new rules for the new world of digital evidence. It explains the challenges courts confront as they translate old protections to a new technological world, bringing the reader up to date on the latest cases and rulings. Informed by legal history and the latest technology, this book gives courts a blueprint for legal change with clear rules for courts to adopt to restore our constitutional rights in the computer age.

And here's some advance praise for the book:

Orin Kerr is the nation's leading expert on how to safeguard the Constitution's guarantee of individual rights in a world of technological change unimaginable to the Framers. Everyone from journalists to Supreme Court justices turn to Kerr for clear-eyed, even-handed analysis, and this thoughtful book shows why. The Digital Fourth Amendment is a call to action for the Supreme Court to protect the Constitution's guarantee of individual privacy. I expect this incisive guide will be invaluable to the justices as they chart the path forward. —Robert Barnes, former Supreme Court reporter for The Washington Post

Orin Kerr is the law professor you wish you'd had-whether you're a lawyer or not. His case to update our search and seizure laws in the era of iPhones and Snapchat is an illuminating and fun ride for nerds of all stripes! —Sarah Isgur, ABC News legal analyst and host of Advisory Opinions

Kerr is the most thoughtful and thought-provoking thinker we have about the Fourth Amendment. In clear and accessible language for non-lawyers, Kerr explains the notoriously uneven road the Supreme Court has travelled, and offers lucid ways out of the thicket caused by the digital revolution resulting in our most personal information being in the hands of big tech companies. —Andrew Weissmann, MSNBC legal analyst and former General Counsel of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

Ensuring that the law remains relevant in the face of rapidly changing technology is a complex and critically important topic-and this is especially true when it comes to the Fourth Amendment. In his insightful and nuanced new book, Orin Kerr, a preeminent scholar of this crucial constitutional provision, articulates a powerful, ultimately optimistic vision for maintaining the vitality of the Fourth Amendment in the digital age.— David Lat, founder of Original Jurisdiction

I'll plan to put up some posts about the argument of the book and why I wrote it when we get closer to the official print publication date, but for now you can get the Kindle version if that's your thing.

The post Kindle Version of "The Digital Fourth Amendment" Is Now Available appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] The DOGE Daze of Regulatory Reform

The new "Department of Government Efficiency" (aka "DOGE"), led by Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, aims to downsize the federal government and tame the federal bureaucracy. DOGE (which is not actually a government department) is seeking help identifying regulations that should be rescinded or repealed. As detailed in a Wall Street Journal op-ed, they aim to achieve these goals through presidential directives, not legislation.

I am skeptical DOGE can fulfill its ambitious objectives through unilateral executive action, particularly without exquisite attention to relevant administrative law constraints. As I explain in an essay for the new Civitas Outlook (where I am a contributing editor), there are few deregulatory shortcuts. Absent legislative action, reforming and undoing rules is typically a long slog.

From my Civitas Outlook article:

It is a core principle of administrative law that amending or revoking a regulation generally takes the same amount of time and effort that it took to adopt the regulation in the first place. If rules governing the amount of energy a dishwasher may use or requiring specific corporate disclosures went through notice-and-comment rulemaking, rescinding such rules will have to go through the same process, even if the agency believes it should never have adopted the rule in the first place. As the Supreme Court explained in 1983 in its landmark Motor Vehicle Manufacturers Association v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co. decision (commonly referred to as State Farm) "the direction in which an agency chooses to move does not alter the standard of judicial review established by law." In doing so, it expressly rejected the argument that it should be easier to rescind regulations than to impose them in the first place. To the contrary, the Court explained "an agency changing its course by rescinding a rule is obligated to supply a reasoned analysis for t change beyond that which may be required when an agency does not act in the first instance." . . .

Musk and Ramaswamy suggest they can get around this problem because the President "can, by executive action, immediately pause the enforcement" of regulations DOGE concludes lack adequate statutory authorization, to "liberate individuals and businesses from illicit regulations never passed by Congress" and buy time for agencies to formally rescind them. If only it were that simple. Many regulations impose burdens on the private sector without requiring direct enforcement. Banks and financial institutions, for instance, must certify compliance with applicable rules, whether they believe an enforcement action is likely. Until existing regulations are repealed, those who refuse to comply act at their own risk. Even in the face of executive branch non-enforcement, regulatory penalties may accumulate, and firms would remain at risk of later enforcement actions by subsequent administrations. Some regulations can also be enforced through citizen suits, such as those filed by environmental and consumer groups and litigious state attorneys general. The President has no authority to "pause" such suits, even if he believes the underlying rules lack legitimate legal authority.

As I note in the article, the first Trump Administration made these same mistakes, particularly at the Environmental Protection Agency (which I wrote about at the time).

Musk and Ramaswamy think their efforts will be aided by the Supreme Court's recent decisions in West Virginia v. EPA and Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimando, but I am skeptical here too.

These decisions were significant rebukes to self-aggrandizing agencies. Both reaffirmed the foundational principle that federal agencies lack the power to do much of anything until Congress delegates power to them—what we might call a "Delegation Doctrine." The EPA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and all of the other alphabet soup agencies were created by Congress and solely imbued with that power Congress sought to bestow. That any of these agencies see a problem and has an idea for a fix, does not license unilateral action absent legislative authorization, nor may agencies rummage around in the U.S. Code seeking previously undiscovered sources for newly sought authority. Pouring new wine out of old bottles is not faithful execution of the laws.

Yet West Virginia, by its terms, is limited to "extraordinary cases," such as those implicating major economic or political significance. It is not a universal trump card. Loper Bright Enterprises will actually make it more difficult for the executive branch to revise some longstanding interpretations of agency authority because courts will have no obligation to accept the new interpretation. (In this regard it is worth remembering that Chevron deference was born out of Reagan administration efforts to deregulate.) Moreover, as The Chief Justice explained in his opinion for the Court, prior agency interpretations upheld by courts remain good law, protected by statutory stare decisis, even if they relied upon Chevron. Both decisions can be deployed against recent agency power grabs, but neither is a simple antidote to long-entrenched regulatory programs.

Musk and Ramaswamy are correct that agencies (and courts) have not always adhered to the principle that they may only exercise the power Congress delegated to them. The Council on Environmental Quality is a case in point, having long asserted the authority to issue regulations implementing the National Environmental Policy Act that Congress never authorized. The Federal Trade Commission is another. Insofar as these and other agency programs, regulations, and initiatives were never properly authorized, the Trump administration should be able to unwind these programs if it so chooses. But this cannot be done immediately through executive edict or without attention to legal niceties.

Deregulation and regulatory reform are worthy goals, but efforts to achieve these ends without attention to legal constraints are likely to do more harm than good. Substantial effort will be expended with little to show for it. The bottom line is quick and dirty efforts will not achieve much deregulation. In future posts, I will try to outline some strategies that might bear more fruit.

The post The DOGE Daze of Regulatory Reform appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] In 2019, I Proposed that SCOTUS Should Use a Lottery To Distribute Tickets. In 2024, SCOTUS Proposes Pilot Lottery Program.

For more than a decade, I have been complaining about how the Court distributes tickets. There are paid line waiters, line cutters, and general chaos when there are disagreements. In November 2019, I offered a series of recommendations of how the process could be improved. One of my ideas was to adopt a lottery:

Attorneys should be able to enter a lottery to obtain a ticket for a specific argument date. There should be a random drawing. Depending on demand, attorneys could request one argument per year, or one argument per sitting. Ideally, the requests should be made after the calendar for a given sitting has been announced. (It does not make sense to reserve a session before you know what case will be argued.) The requests should be made online through a system that verifies an attorney is in good standing. Confirmation can be sent by email.

Attorneys who lose the lottery, or do not make a timely request, can still show up the same day and wait on the bar line. They would be able to listen to the arguments from the lawyer's lounge. In the event that a lottery winner does not show up, one of the attorneys from the lounge can be upgraded to the chamber.

This process would eliminate most of the unfairness of waiting outside, including line-cutting. The lottery would also ensure that people do not travel at great expense for an argument they cannot attend in person.

If the lottery process is successful for members of the bar, it should be extended to the general public. It will be more difficult to implement a lottery for members of the general public, who are not vetted. But the process would be feasible. Adding a degree of randomness would ensure that people do not have to wait in the cold and rain for days outside the Court. Moreover, a lottery would ensure that a range of people from different backgrounds with different interests can attend--not just those who have the means to camp out for days on First Street.

In May 2020, Amy Howe promoted my idea at SCOTUSBlog:

The court has traditionally been reluctant to get involved in policing the public line: Officers normally don't do much beyond handing out tickets at around 7:30 a.m. But other small steps by the officers could help to increase the perception of fairness – for example, handing out tickets or wristbands much earlier in the process (a step that many lawyers in the bar line might also welcome) to ensure that later arrivals don't join the line and take a spot that should belong to someone who has spent many hours waiting. Blackman has recommended a much more dramatic step: Scrap the line system altogether in favor of a lottery. Such a system would not only address some of the social-distancing issues that the court is likely to face for many months to come, but (even if it included only some of the public seats) it would also give some members of the public more certainty – especially if they plan to travel to the court from out of town – that they will actually get a seat.

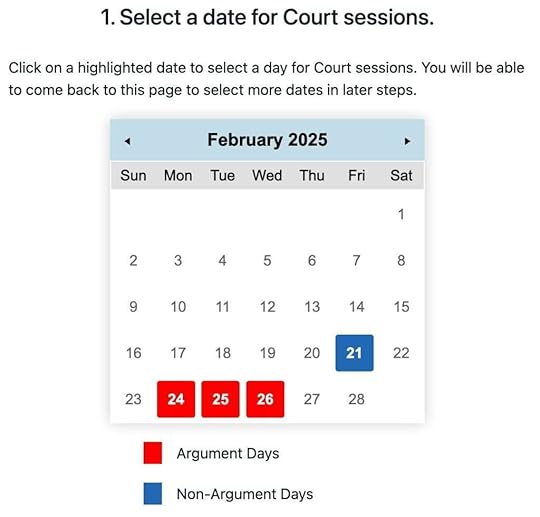

Today, the Court announced a new lottery pilot program:

The Supreme Court is implementing a pilot program in which members of the public may apply for Courtroom seating through a fully automated online lottery. Individuals who receive tickets through the lottery will be able to come to the Court knowing that they have reserved seating for a particular argument or non-argument session.

The pilot program will begin with the February 2025 argument session. Starting today, members of the public can access the lottery for the February 2025 session through a link on the Court's website. The deadline to submit an application to the lottery is 5 p.m. Eastern time, four weeks before the particular argument or non-argument session. Three weeks before the session, the Court will notify applicants by email as to whether they have received tickets, have not received tickets, or are on a wait list. Applications for future lotteries will open shortly after a particular monthly argument calendar is released.

During the pilot program, the Court will continue to provide some seating for the public on a first-come, first-seated basis. Before a session begins, a line will form on the sidewalk on East Capitol Street adjacent to the Court building. Seating for the Bar section will remain on a first-come, first-seated basis during the pilot.

Additional information about the online ticketing system is available via the "Courtroom Seating" quick link on the Court's website: https://www.supremecourt.gov.

Bravo! What an elegant, and needed solution to the chaos on the Supreme Court line.

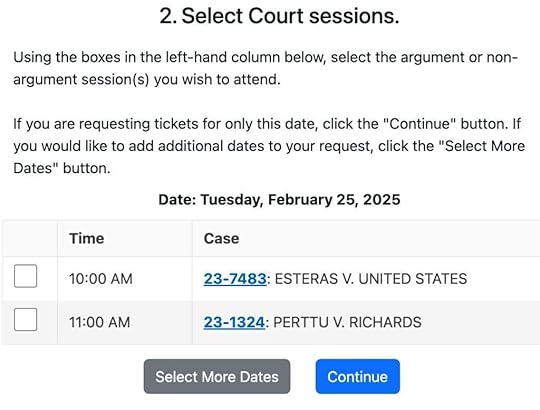

The Courtroom Seating section offers some more information on the FAQ. The ticket is only for a single case. You cannot attend both arguments. This is a very smart move, and ensures that tickets are only allocated for a particular case. More seats will now be open. You can request up to four tickets. There is also a wait list, which seems extremely useful if a guest has to cancel. Notifications for the wait list are provided up to three days in advance. That would be most useful to people who are local in DC, but not those who have to make travel arrangements. Also, the lottery system applies to non-argument sessions, such as opinion hand-downs. I'm not sure how it will work in June when hand-down dates are added with a few days notice. Lotteries may not be available for those dates. For now, at least, members of the bar still have to wait on line.

The system is very easy to use and elegant.

First, you select a date of a session:

Second, you can select one or more cases to enter the lottery for:

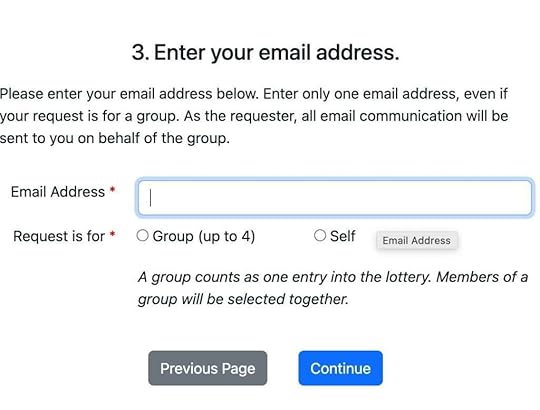

Third, enter your contact information, to select up to four tickets per argument.

Again, bravo to the Court. They got this one exactly right. And it should be expanded. As someone who arrived to the Bar Line around 5 AM for an argument this term, I think the lottery should be extended to bar members. For big cases, the parties often gobble together many tickets for their colleagues, leaving other lawyers stuck in the lounge. A bit of randomness would be useful here.

The post In 2019, I Proposed that SCOTUS Should Use a Lottery To Distribute Tickets. In 2024, SCOTUS Proposes Pilot Lottery Program. appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] $230K Defamation Award in N.Y. #TheyLied Case Against Apartment Owner Who Alleged Manager Sexually Assaulted Her

From a decision Friday by Manhattan trial judge Judy Kim:

Plaintiff, [a] resident building manager … brings this defamation action alleging that defendant Jean Mamakos, who owns an apartment in the Building, defamed him by falsely stating, repeatedly, that he had sexually assaulted her. Plaintiff alleged … [that] defendant informed the police officers who reported to the Building that she wished to file a complaint against plaintiff for sexual harassment and sexual assault (though no complaint was ever filed). Later, at a meeting of the Building's board …, defendant stated that plaintiff had threatened to shut off her water unless she performed "sexual favors." {Plaintiff also testified that a plumber who provided services in the Building told him that defendant had repeated these allegations ….} Thereafter, … defendant distributed a flyer to every apartment in the Building stating as follows:

I was sexually attacked/assaulted by super, Joseph Coutelier, in August. I'm the owner in the Colonnade, apartment 32-F for 35 years. If you have anything to add regarding the behavior of this person, I'd be interested in your contacting me. Jean Mamakos

Plaintiff sued; eventually, defendant's lawyer withdrew, defendant didn't hire a new lawyer, and then failed to appear at a conference and otherwise comply with court rules. The court therefore, in effect, granted plaintiff default judgment:

As a result of these failures, this Court (Hon. Frank P. Nervo) issued an order … striking defendant's Answer and setting this matter down for inquest…. At the inquest, plaintiff credibly testified as to the events set forth in the complaint and that defendant's false statements caused him great anxiety about the security of his job and his relationship with the Building's tenants. Defendant appeared at the inquest and argued that plaintiff should not receive any damages because plaintiff had, in fact, "sexually accosted" her in her apartment….

Plaintiff has, through his testimony, met the "minimal" threshold to establish the prima facie validity of his claim…. Though no special harm was established, defendant's false claim that plaintiff sexually assaulted her, a serious crime, constitutes defamation per se.

The court rejected plaintiff's request for a preliminary injunction:

"A permanent injunction may issue where plaintiff demonstrates that a violation of a right [is] presently occurring, or threatened and imminent, that [he has] no adequate remedy at law, that serious and irreparable harm will result absent the injunction, and that the equities are balanced in [his] favor." In this case, nothing in the record raises the possibility of prospective harm to plaintiff, as there is no indication that defendant has continued to defame plaintiff during the pendency of this action.

Moreover, even if defendant does engage in such conduct in the future, an adequate remedy exists at law through a subsequent civil or criminal proceeding, ordinarily "the appropriate sanction for calculated defamation or other misdeeds in the First Amendment context," while the prior restraint sought by plaintiff is "strongly disfavored" and generally "not permissible merely to enjoin the publication of libel."

(My research suggest that some New York cases do allow permanent injunctions against repeating statements that had been found defamatory, but others do take a different view.)

But the court did award compensatory damages:

Here, the extremely serious allegations by defendant, which were circulated through the entire Building—which is both his home and workplace—necessarily injured plaintiff's standing in the community, causing him distress. To determine the appropriate compensatory damage, the Court looks to "cases with comparable fact patterns in order to determine what constitutes reasonable compensation" and finds the closest analogue in a trio of Appellate Division, Third Department cases involving plaintiffs who were falsely accused of sexually assaulting children to determining compensatory damages. The compensatory damages awarded in those cases, after adjusting for inflation, ranged from slightly below $200,000.00 to over $300,000.00. To the extent these cases are distinguishable insofar as they involve allegations that plaintiff had sexually assaulted a child, "one of the most loathsome labels in society," the Court concludes that a compensatory damage award of $200,000.00 is appropriate.

And the court held that punitive damages should also be awarded:

Here, plaintiff has established that defendant knew that her statements were untrue and that they would, if credited, damage plaintiff's relationship with the Building's board and residents, and had no other motive aside from animus in making these statements. Indeed, the series of events detailed by plaintiff indicates a clear effort by defendant to have him fired. Looking once again to the Third Department cases referenced above, which awarded punitive damages of nearly $35,000.00 and $47,000, after adjusting for inflation, the Court concludes that punitive damages in the amount of $30,000.00 are appropriate.

Plaintiff was thus awarded $230K plus interest, plus $6K in attorney fees "for the costs of his opposition to defendant's motion to vacate," which had been found to be frivolous.

The post $230K Defamation Award in N.Y. #TheyLied Case Against Apartment Owner Who Alleged Manager Sexually Assaulted Her appeared first on Reason.com.

[Paul Cassell] Should Defendants Be Allowed to Subpoena Rape Victims and Force Them to Testify at Rape Shield Hearings?

In the federal system and all states, "rape shield" rules require pre-trial hearings on whether evidence relating to a rape victim's prior sexual history is admissible at trial. For example, Utah's Rule of Evidence 412 (which parallels Federal Rule of Evidence 412) requires a defendant who intends to introduce a victim's prior sexual history evidence to make a detailed proffer of the relevance and purpose of the proposed evidence. The trial judge then holds a hearing and determines the admissibility of the evidence. But what if the defendant wants to subpoena a victim to the hearing and question her about prior sexual history as part of that determination? Is forcing a rape victim to testify consistent with the rule?

Tomorrow, the Utah Supreme Court will hearing argument on this question. Along with the Utah Crime Victim's Legal Clinic, I represent a minor victim of rape. I will argue that forcing rape victims to testify at rape shield hearings is inconsistent with the structure and purpose of such hearings. A Utah decision on this issue could be influential, since the text of Utah's rape shield rule is similar to many others.

Here is the opening paragraph from my brief for the victim, T.T.:

This appeal involves an important question regarding the proper operation of Utah's "rape shield" rule, Utah R. Evid. 412. The appeal is brought by T.T. from a district court order denying T.T.'s motion to quash a defense subpoena, which seeks to force her to testify at a rape shield hearing to be held under Utah Rule of Evidence 412. Because Utah's rape shield rule is designed to prevent rape victims from being forced to testify about sexual issues, the district court order forcing T.T. to testify should be overturned.

The underlying facts in the criminal case involve a rape charge alleging that fifteen-year-old T.T. was too intoxicated to consent to intercourse—intercourse Defendant concedes occurred. But Defendant seeks to force T.T. to be questioned by defense counsel at a rape shield hearing about her prior sexual behavior. The district court held that Defendant had made a sufficient "threshold" showing to force T.T. to testify at the rape shield hearing—but did not find specifically that the sexual behavior evidence was admissible at trial. This ruling stands Rule 412 on its head, converting it from a rule designed to protect victims from being examined about their presumptively inadmissible prior sexual history into a rule that requires such questioning. This Court has repeatedly held that a rape victim's prior sexual history is protected by "a presumption of inadmissibility," State v. Beverly, 2018 UT 60, ¶56 n.58 (quoting State v. Boyd, 2001 UT 30, ¶41). And this Court has recognized that the purpose of a Rule 412 hearing is not "to attempt discovery of evidence." State v. Blake, 2002 UT 113, ¶7. This Court should give effect to these principles and reverse the order forcing T.T. to testify at the rape shield hearing.

And here is the defendant's opening argument:

This appeal presents the question of whether an alleged sexual assault victim may be subpoenaed to testify at an in camera hearing conducted pursuant to Utah Rule of Evidence 412 (Utah's "Rape Shield" law) for the purposes of determining the admissibility of evidence proposed to be admitted under an exception to Rule 412's general prohibition against evidence of an alleged sexual assault victim's past sexual conduct. The victim in this matter unduly relies on the "presumptive inadmissibility" of the proposed evidence to argue that she should not be required to testify in a closed, in camera under Utah Rule of Evidence 412 regarding her past sexual conduct with Defendant. In response, Defendant shows that the evidence is not prohibited by Rule 412, is relevant and admissible under applicable case law, and that the district court properly determined that it should hear the testimony proposed to be elicited from the alleged victim prior to making a final ruling on its admissibility. In declining to grant the alleged victim's motion to quash the subpoena issued for her testimony at the Rule 412 in camera admissibility hearing, the district court properly balanced the alleged victim's constitutional and privacy protections as a crime victim with the Defendant's right to present a defense.

The problem with the defense position is that, if accepted, it would essentially mean that in every rape case where a defendant is seeking to introduce prior sexual history evidence, he would subpoena a victim and then examine her about the details of the prior sexual history. This would convert rape shield rules designed to keep rape victims from testifying about sensitive sexual issues into engines that would force them to testify. Interestingly, the federal rape shield rule (Fed. R. Evid. 412) originally contained a provision authorizing trial judges to take testimony on admissibility issues in rape shield hearings. But in 1994, this language in the federal rules was stripped out. Like the current version of the federal rule, the Utah rule contains no language authorizing a victim's testimony at the rape shield hearing. Instead, the rule simply gives the victim "a right to attend and be heard" at a rape shield hearing. Utah R. Evid. 412(c)(3) (emphasis added). In extending a "right" to victims and an opportunity to "be heard," the Rule's structure provides victims an opportunity to address the potential admissibility of such evidence—not suffering the potential indignities associated with being questioned by defendants accused of raping them.

If you're interested in all the briefing, I link here the victim's brief, the State's (supporting) brief, the defendant's brief, and the victim's reply. Obviously, I hope that the Utah Supreme Court agrees with my arguments tomorrow.

P.S. In referring to rape "victims" in this post, I am (of course) aware that defendants are presumed innocent of the charges against them. But Utah's rape shield rule (like many others) sweep within its protections the alleged victim in a rape case (see Utah R. Evid. 412(d)), since otherwise the rule would essentially have no effect.

The post Should Defendants Be Allowed to Subpoena Rape Victims and Force Them to Testify at Rape Shield Hearings? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Thursday Open Thread

The post Thursday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

December 11, 2024

[Josh Blackman] Making Sense of the 7-1-1-8 Split in Environment Texas Citizen Lobby v. ExxonMobile

On Wednesday, the en banc Fifth Circuit decided Environment Texas Citizen Lobby v. ExxonMobil. The procedural posture of this case resides in the ninth circle of Dante's Inferno. I won't even try to explain it here. Instead, I will try to make sense of the extremely unusual split.

Reuters reported the case as a 9-8 split. Not quite.

The case was heard before seventeen members of the en banc court: Elrod, Davis, Jones, Smith, Stewart, Richman, Southwick, Haynes, Graves, Higginson, Willett, Duncan, Engelhardt, Oldham, Wilson, and Douglas. (Judge Ramirez joined the court after the case was submitted so she did not participate). Simple math would suggest that a majority of a seventeen member court would require nine votes. But there is no actual nine member majority.

Seven members of the court would have affirmed the District Court's decision from April 2017: Davis, Stewart, Southwick, Haynes, Graves, Higginson, and Douglas.

One member of the court would have reinstated a panel majority opinion from 2022: Chief Judge Elrod.

Eight members of the Court would have reversed the District Court's decision: Jones, Smith, Richman, Willett, Duncan, Engelhardt, Oldham, and Wilson.

For those of you counting at home, you will notice I've listed sixteen judges so far. Who is #17? Judge Ho. He did not vote to affirm or reverse. Instead he voted to dismiss rehearing en banc as improvidently granted--a DIG in the parlance. The Supreme Court will often DIG a case, but on rare occasion, an individual Justice will vote to DIG. Justice Gorsuch has individually DIG'd a few cases.

As I count things, the split is 7 votes to affirm the district court, 8 votes to reverse the district court, and 2 votes to do something else. Is your head spinning? Well then turn to 2 of the PDF. There is a paragraph labelled "Per Curiam." That paragraph concludes, "We accordingly AFFIRM the judgment of the district court, dated March 2, 2021." I use scare quotes quite deliberately. Per Curiam is Latin for "by the Court." But there is not a single thing that nine members agreed upon. Who exactly is the "We" in that final sentence. I can only count to seven. This paragraph labelled "Per Curiam" cannot possibly be "by the Court." Who assembled the second page of the PDF? I have more questions than answers.

Is your head still spinning? Well, check the docket. Immediately after the opinion was filed, a judgment was entered. It states:

IT IS ORDERED and ADJUDGED that the judgment of the District Court is AFFIRMED.

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that Appellants pay to Appellees the costs on appeal to be taxed by the Clerk of this Court.

W. Eugene Davis, Circuit Judge, concurring, joined by Stewart, Southwick, Haynes, Graves, Higginson, and Douglas, Circuit Judges.

James C. Ho, Circuit Judge, in support of dismissing rehearing en banc as improvidently granted.

Edith H. Jones, Circuit Judge, joined by Smith, Richman*, Willett, Duncan, Engelhardt, Oldham, and Wilson, Circuit Judges, dissenting.

Priscilla Richman, Circuit Judge, dissenting.

Andrew S. Oldham, Circuit Judge, joined by Jones, Smith, Willett, Duncan, Engelhardt, and Wilson, Circuit Judges, dissenting.

By what authority did the Court issue that the judgment of the District Court should be affirmed, if only seven out of seventeen judges voted to affirm the judgment of the District Court?

If you've followed this far, hang on. This will get messy.

The starting point for this analysis is Judge Ho's concurrence. He explains what the effect of his DIG is:

When eight judges would affirm, eight judges oppose affirmance, and one would dismiss as improvidently granted, then our court lacks a sufficient majority to do anything other than affirm—as Judge Richman's dissent appears to acknowledge.

I think that Judge Ho would group Judge Elrod with the Davis-Seven as affirming. But Elrod was voting to affirm something different than the Davis-Seven. The Davis-Seven would affirm the District Court's decision. Elrod would affirm a panel opinion. But maybe those can be lumped together for purposes of determining whether a court is evenly-divided. I'm not sure.

If that math is right, there are eight votes to affirm (Elrod+Davis-Seven) and eight votes to not affirm (the Jones dissent). Judge Ho, by DIGing the case, did not cast his judgment to affirm or not-affirm, so he falls into neither camp. As a result, the en banc court effectively split eight-eight. It is as if a sixteen member court (with a recusal) was evenly divided. And what happens if the en banc court is evenly divided? Ho says that the judgment of the lower court would be affirmed.

Judge Richman wrote a separate partial dissent that I think supports Ho's reading:

The en banc court should have issued a simple per curiam opinion that recognizes where the votes lie, based on the divisions among us, and that announces the judgment of the en banc court, which is affirmation by operation of law because a majority was lacking after the en banc court considered the issues.

In other words, absent a majority opinion for the en banc court, the default rule "by operation of law" is to affirm the lower court decision.

I want to focus on this phrase, "by operation of law." What law? Neither Judge Richman nor Judge Ho cites any such rule. You can search the Fifth Circuit's local rules to find what happens if there is an evenly divided en banc court, but there is nothing there. Fifth Circuit Rule 41.3 discusses what happens if the en banc court loses a quorum:

41.3 Effect of Granting Rehearing En Banc. Unless otherwise expressly provided, the granting of a rehearing en banc vacates the panel opinion and judgment of the court and stays the mandate. If, after voting a case en banc, the court lacks a quorum to act on the case for 30 consecutive days, the case is automatically returned to the panel, the panel opinion is reinstated as an unpublished (and hence nonprecedential) opinion, and the mandate is released. To act on a case, the en banc court must have a quorum consisting of a majority of the en banc court as defined in 28 U.S.C. § 46(c).

But the rule is silent about what happens if the en banc court evenly divides. It is a poorly-kept secret that the Fifth Circuit has secret "nonpublic internal court policies" that members of the bar are not allowed to read. (Judge Willett lifted the veil on those rules in 2019.) Still, I doubt any such rule exists about the en banc court.

We all know that a 4-4 tie at the Supreme Court affirms the lower court "by operation of law." Certainly, the Supreme Court has such a rule inside its voluminous rule book? Right? It does not. A 2020 student note in the Houston Law Review by Aditi Deal observed the "marked lack of rules about equally divided votes, recusals, or vacancies." Instead, the rule stems from a FedCourts classic, Hayburn's Case (1792). That decision split 3-3, which had the effect of denying mandamus. Three decades later in The Antelope (1825), Chief Justice Marshall wrote that "Where the Court is equally divided, the decree of the Court below is of course affirmed, so far as the point of division goes." It's not clear there was any actual law to support this holding, especially since there was no majority opinion! Maybe this was the practice in England, but it was never firmly established in any positive American law. Maybe this model is something of a rule of necessity? In other words, if a court has to issue some judgment, this rule allows the evenly-divided court to issue some judgment, even if it lacks majority support.

This point brings me to an opinion I have not yet mentioned: Judge Oldham's dissent, which was joined by seven other members. Much of Oldham's dissent focuses on the standing issue and the merits, which I will not address here. Instead, I will articulate the differences--as I see them--between how Judges Ho and Oldham view this case, and the judicial power more broadly.

Oldham articulates that that a court must issue a judgment, full stop. Appellate judges are not required to write opinions. However they have to resolve the case in front of them: affirm or reverse some other judgment. It is true that en banc is a discretionary jurisdiction, and there is no obligation to grant rehearing en banc. But once a majority of the Court vacates the panel opinion, it takes a majority of the Court to render some new judgment, for example, to reinstate the panel opinion. If a majority of the court does not coalesce to render some new judgment, the case will remain in a state of limbo.

But what about the more conventional eight-eight split, where the judgment below is affirmed "by operation of law" (to use Judge Richman's lingo)? There is no actual statute or court rule that provides as such. Perhaps there is some ancient Fifth Circuit panel, or en banc precedent, that explains what happens with an evenly-divided court. But I'm not certain than an en banc decision that resolves a particular case, can establish a court rule of how to render judgments in all other cases. I think something like this would have to be adopted by a majority of the court as a rule of the court--but I am not certain on this last point.

Absent such a rule, on what basis can the clerk enter a judgment of "affirm" if a majority of the Court has not acted? Seriously!? In this case, who instructed the clerk to enter an "Affirm" judgment on the docket? Did the clerk make a judgment about how to construe Judge Ho's opinion? I do not mean to criticize the clerk, or any member of the Fifth Circuit here. This is an exceptionally complicated case. I am simply raising questions that are not evident to me from the face of the opinion.

The implication from Oldham's concurrence are significant. As I read his opinion, if a judge on a multi-member court is the deciding vote, he has an obligation to render his own judgment, so that the court as a whole can render its judgment. And according to Judge Oldham, a DIG is not a judgment at all. In the run-of-the-mill en banc case, where there are sixteen votes to reverse the district court, and one vote to DIG, I don't think Judge Oldham would see any obligation for the judge to render a judgment. But with an effective 8-8 split, where Judge Ho is the deciding vote, I think Oldham sees Judge Ho as having an obligation to vote one way or the other to ensure the en banc court issues some judgment. And, according to Oldham, Ho's failure to cast a vote was a violation of some judicial duty.

I take it that if Judge Ho had simply concurred in the judgment, and wrote exactly what he wrote, then Judge Oldham would have had no quarrel. There would have then been eight square votes to affirm, in which case, per The Antelope, the judgment of the lower court would be affirmed. The problem for Judge Oldham is that Judge Ho did not concur or dissent from the judgment.

What is the basis for this obligation? Judge Oldham's opinion reads like it was written by a FedCourts professor (which he is). It is fairly dense, and goes back to the judicial duty in Roman times. (Richard Epstein would be proud.) Judge Ho responds, "I like history too, but nothing in his historical gesturing remotely demonstrates how justice or tradition requires appeal before seventeen judges rather than three." Judge Oldham acknowledges, "You might be wondering: What does any of this have to do with courts of appeals and en banc rehearing?" He then answers his own question. "The answer is: Nothing."

But I don't think it is quite nothing. If Judge Oldham is correct, and there is some sort of obligation for a judge to vote for a judgment to ensure that his multi-member court issues a judgment, then this history is extremely relevant, and the criticism of Judge Ho's opinion is apt.

Is Judge Oldham correct? At this point, I would respond "not proven." I have no idea if such an obligation exists. But the place to make this argument for the first time is not in the heat of a contentious en banc battle where you are trying to count thumbs up or thumbs down, pollice verso. Rather, this sort of robust theory should be developed outside the coliseum where the outcome of this bout is unknown.

The fact pattern here is so bizarrely unique, I am doubtful any multi-member court has ever dealt with something like this. To be sure, en banc courts have dismissed grants of en banc as improvidently granted. (I wrote a post on this issue after the Tenth Circuit DIG'd a grant of en banc in the bump stock case). But in that case, there was a clear majority of the Court that voted to DIG. And I don't take Judge Oldham to having any objection if a majority of the court wishes to vacate its grant of en banc (a VIG as he calls it).

Perhaps there is a classic piece of scholarship that could inform this inquiry: Lon Fuller's The Case of the Speluncean Explorers. In this fictional case, the Supreme Court of Newgarth considers whether to affirm the death sentence of hikers who were trapped in a cave, and resorted to cannibalism. There is a five member court. Two members vote to affirm the death sentence. Two members vote to reverse the death sentence. The fifth member of the Court, Justice Tatting, declines to vote. He found the case so difficult that he simply withdrew:

Since I have been wholly unable to resolve the doubts that beset me about the law of this case, I am with regret announcing a step that is, I believe, unprecedented in the history of this tribunal. I declare my withdrawal from the decision of this case.

Not quite a DIG, but it has the same effect. When it becomes clear that the case is split 2-2, Justice Tatting is asked to reconsider his vote:

I have been asked by the Chief Justice whether, after listening to the two opinions just rendered, I desire to reexamine the position previously taken by me. I wish to state that after hearing these opinions I am greatly strengthened in my conviction that I ought not to participate in the decision of this case.

What follows is the judgment of the Court. And to be clear, there is not a majority of the Court to support any such judgment:

The Supreme Court being evenly divided, the conviction and sentence of the Court of General Instances is affirmed. It is ordered that the execution of the sentence shall occur at 6 a.m., Friday, April 2, 4300, at which time the Public Executioner is directed to proceed with all convenient dispatch to hang each of the defendants by the neck until he is dead.

Sounds familiar, huh?

This is the third time I've cited the Speluncean Explorers in the last few months. One of the Justices of Newgarth asked the Executive for clemency. And in Roberson v. Texas, Justice Sotomayor asked Governor Abbott for an executive reprieve. (The aftermath of that case in the Texas legislature and the Supreme Court of Texas demonstrates that Sotomayor was wrong.) And in Glossip v. Oklahoma, we may yet see a request for executive clemency if the Court evenly divides 4-4.

I hope this post was helpful. This was one of the more confusing en banc decisions I can recall. I agree with much of the frustration all of the judges expressed with such splintered opinions. And I feel for the parties who have to make sense of this mess. Perhaps one of the few upshots is that, as Judge Ho noted, there is no circuit precedent established, and a new three-judge panel can resolve the issue fresh. Still, I'm not yet persuaded any Article III judge has any obligation to cast a vote to avoid these situations. I'm sure that many judges simply join en banc opinions, even if they do not agree in whole, for the sake of clarity of the law. That is certainly one way to approach the judicial function, but it is by no means a judicial duty.

The post Making Sense of the 7-1-1-8 Split in Environment Texas Citizen Lobby v. ExxonMobile appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers