Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 189

January 13, 2025

[Ilya Shapiro] Lawless I: The Illiberal Takeover of Legal Education

Thanks to Eugene for inviting me to participate in the Volokh Conspiracy's venerable tradition of the author's weeklong guest-blog. I'm particularly excited for the opportunity not only to preview my new book, Lawless: The Miseducation of America's Elites, but to dispel some Ilya Confusion. Then again, it may also make Ilya Confusion harder to discern, because the most common way I recognize interlocutors who are thinking of "the other Ilya" (Somin) is when they reference my blogging on this site. Well, now we're both VC bloggers.

In any event, my new book Lawless uses my "lived experience"—what one friend called "the Troubles"—as a jumping-off point for diving into the illiberal takeover of law schools and the legal profession. It discusses failures in (1) bureaucracy, (2) ideology, and (3) leadership, and (4) proposes reforms. My remaining posts will cover each of those numbered items.

VC readers no doubt know my story. When I accepted Randy Barnett's offer to become executive director of Georgetown's Center for the Constitution, I thought it would be a chance to have a different kind of impact on public affairs. After nearly 15 years at the Cato Institute, having become a vice president and published a critically acclaimed book on the Supreme Court, I was looking for a new challenge. Well, that's what I got, but not quite how I'd imagined it.

In late January 2022, when news of Justice Stephen Breyer's retirement broke, I tweeted in opposition to President Biden's decision to limit his nominee pool by race and sex. I argued that Sri Srinivasan, the chief judge of the D.C. Circuit—who also happens to be an Indian-American immigrant—was the best candidate for a Democratic president, meaning that everyone else was less qualified. So if Biden kept his promise, he would pick what, given Twitter's character limit, I characterized as a "lesser black woman." Then I went to bed.

Overnight, a fire storm erupted on social media. I deleted the tweet and apologized for my inartful choice of words, but stood by my view that Biden should've considered "all possible nominees," as 76% of Americans agreed in a poll by that right-wing outlet ABC News. (I stand by that view to this day.) But it was too late. My ideological opponents were out for blood, or at least my new job—even before I was due to assume it on February 1.

That day, January 27, was the second-worst day of my life, after another January day nearly 25 years earlier when my mom died. I thought that I had blown up my life and killed my career. Everything I had worked for over decades, the sacrifices my parents made in getting me out of the USSR, the life my wife and I were building for our two young sons—we added twins later that year, our "cancellation babies"—all of it was crumbling. Over a tweet.

Never mind that no reasonable person could construe what I said to be offensive. It's willful miscomprehension to read my tweet to suggest that "the best Supreme Court nominee could not be a Black woman," as Dean William Treanor did in a statement that afternoon. Although my tweet could've been phrased better, as I readily admitted, its meaning that I considered one candidate to be best and thus all others to be less qualified is clear. Only those acting in bad faith would misconstrue what I said to suggest otherwise.

Thanks to friends with public platforms and private backchannels to Dean Treanor, I wasn't fired during those initial four days of hell. Instead, I was onboarded and immediately placed on paid administrative leave pending an investigation into whether I violated university policies on antidiscrimination and harassment. That investigation continued for more than four months of purgatory, during which I was prohibited from even setting foot on campus.

It's become clear now that the "investigation," conducted by both Human Resources and an office with the Orwellian title of Institutional Diversity, Equity and Affirmative Action (IDEAA), was a sham. And that the process was the punishment. On June 2, about a week after students left campus, I was reinstated on the technicality that I hadn't been an employee when I tweeted and so wasn't subject to discipline under the relevant policies.

I celebrated that technical victory, but further consideration showed that Georgetown had made it impossible to fulfill the duties I had been hired to perform. After full analysis of the IDEAA report that hit my email inbox later that afternoon, and after consulting with counsel and trusted advisers, I concluded that remaining in that job was untenable.

I won't rehash the explanation here; you can read it in a Wall Street Journal oped, and indeed in my June 6 resignation letter. But suffice it to say, Georgetown had implicitly repealed its vaunted free speech and expression policy and set me up for discipline the next time I transgressed progressive orthodoxy. Instead of participating in that slow-motion firing, I made what lawyers call a "noisy exit."

My case was no anomaly. Institutional cultures are so weak, thanks to a bureaucratic explosion and increase in academic activists, that administrators are easily overwhelmed by moral panics. This pernicious dynamic is reminiscent of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, in which students publicly shamed professors to scare them into ideological obedience.

And then there's the disruption of outside speakers. Indeed, one "fun" aspect of my Georgetown purgatory was being shouted down at the University of California Hastings College of Law (since renamed UC College of the Law, San Francisco, because of Mr. Hastings's political incorrectness). That was no isolated incident, not even in that one month of March 2022. The week after, a similar thing happened at Yale, ironically over a panel bringing together lawyers from the left and right who agreed on the importance of free speech. Dean Heather Gerken basically buried her head in the sand. Then it happened again at the University of Michigan, when students obstructed a debate on a Texas abortion bill. Then it happened a year later with the shutdown of Fifth Circuit Judge Kyle Duncan at Stanford.

This is all particularly worrisome because it's going on at law schools. If an English or sociology department is led astray, that's unfortunate and a loss to the richness of life and the accumulation of human knowledge. But the implosion of legal education has much more dire consequences, as I told Tunku Varadarajan for the Wall Street Journal's "weekend interview" feature in March 2023. Law schools train the gatekeepers of our institutions and of the rules of the game on which American liberty and prosperity sit.

These future lawyers will be bringing cases, occupying corporate counsel's offices, and filling big-firm partnership ranks. It would be a disaster for our way of life to have them think that applying the law equally to all furthers white supremacy or that one's rights depend on one's level of privilege—or that due process protects oppressors and perpetuates injustice.

The problem isn't limited to canceling professors and shouting down speakers. The illiberal takeover of law schools involves the clash between the classical pedagogical model of legal education and the postmodern activist one. The dynamic was crystallized in Stanford DEI dean Tirien Steinbach's memorable question, "Is the juice worth the squeeze?" It's just a cute way of giving ideological opponents a heckler's veto.

These are systemic issues. What we're seeing isn't the age-old complaint about liberal professors, but spineless university officials who placate the radical left. I've long been an advocate for free speech, constitutionalism, and classical liberal values, but only by living through this crucible did I truly understand the crisis we face.

The post Lawless I: The Illiberal Takeover of Legal Education appeared first on Reason.com.

January 12, 2025

[Ilya Somin] Easing Zoning Restrictions Can Facilitate Rebuilding After the LA Fires

Homes burning in Pacific Palisades, CA. (Atlas Photo Archive/Cal Fire / Avalon/Newscom)

Homes burning in Pacific Palisades, CA. (Atlas Photo Archive/Cal Fire / Avalon/Newscom)

Much of the debate over the horrible wildfires afflicting the Los Angeles areas focuses on issues outside my expertise. Thus, I'm not going to opine on such questions as the role of climate change in causing the fires, and whether federal, state, and local governments, have done a good job of running the LA fire department and managing wildfire risk more generally. There is enough ill-informed pontification on these issues already. One relevant issue, however, is within my expertise: zoning and housing policy. Easing zoning restrictions on housing construction could help the city rebuild faster and find new homes for those displaced by the fires. It could also help alleviate the area's longstanding housing crisis.

Even before the fire, the LA region had a serious housing shortage, caused in large part by exclusionary zoning. Some 78% of the residential land in LA is zoned for single-family residences only, which makes it extremely difficult to build new housing in response to demand, especially multifamily homes affordable for working and lower-middle class people.

The fires have destroyed an estimated 12,000 structures, a figure that is likely to rise before the conflagration ends. Not all these structures are homes. Some are garages, commercial buildings, and other nonresidential facilities. Nonetheless, there is no doubt the fires have wiped out thousands of homes, displacing tens of thousands of people. And while much media attention has focused on the losses suffered by wealthy Hollywood celebrities, most of those displaced are less affluent folk who cannot easily find new homes.

Zoning and housing expert M. Nolan Gray (in the Atlantic), and Reason writer Jack Nicastro have helpful articles summarizing how exclusionary zoning rules have contributed LA's housing crisis, and how easing them will make it easier to rebuild. They also explain how zoning restrictions made the region more vulnerable to wildfires, by pushing development into more dangerous areas, and making it difficult or impossible to build more fire-resistant housing.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom recently issued an executive order suspending some types of regulatory obstacles to housing construction in areas affected by the fire, such as burdensome review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). That's a step in the right direction. But its impact will be very limited unless state and local governments also suspend zoning restrictions that make it difficult or impossible to build multifamily housing throughout much of the region.

Moreover, Newsom's order also extends enforcement of anti-"price gouging" restrictions in the affected area. Such laws prevent sellers - including providers of construction materials - from raising prices in regions affected by natural disasters. As economists have long pointed out, such restrictions make reconstruction more difficult by reducing incentives for suppliers to increase delivery of needed goods.

In the aftermath of the fires, construction supplies will be more needed in LA than in most other regions. We want prices in the area to rise, so that producers will get the signal to send more of these types of goods there. Price controls will only exacerbate shortages, and make rebuilding take longer.

In a recent Texas Law Review article my coauthor Josh Braver and I have argued that exclusionary zoning restrictions on housing construction are unconstitutional violations of the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment. For a more succinct summary of our argument, see our June article in the Atlantic.

The post Easing Zoning Restrictions Can Facilitate Rebuilding After the LA Fires appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Ilya Shapiro Guest-Blogging About "Lawless: The Miseducation of America's Elites"

I'm delighted to report that Ilya Shapiro (Manhattan Institute) will be guest-blogging this week about this new book of his. From the publisher's summary:

In the past, Columbia Law School produced leaders like Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Now it produces window-smashing activists.

When protestors at Columbia broke into a building and created illegal encampments, the student-led Columbia Law Review demanded that finals be canceled because of "distress." At Stanford, chanting activists, egged on by an associate dean, drove away a federal judge. Yale's hostility to free speech led more than a dozen federal judges to boycott the school for clerkship hiring.

Law schools used to teach students how to think critically, advance logical arguments, and respect opponents. Now those students cannot tolerate disagreement and reject the validity of the law itself. And yet, rioting Ivy Leaguers are the same people who will hold important government positions, fight constitutional lawsuits, and advise Fortune 500 companies.

In Lawless, Ilya Shapiro explains how we got here and what we can do about it. The problem is bigger than radical students and biased faculty—it's institutional weakness. Shapiro met the mob firsthand when he posted a controversial tweet that led to calls for his firing from Georgetown Law. A four-month investigation eventually cleared him on a technicality but declared that if he offended anyone in the future, he'd create a "hostile educational environment" and be subject to the inquisition again. Not being able to do the job he was hired for, he resigned.

This cannot continue. In Lawless, Shapiro reveals how the warping of higher ed—and especially the illiberal takeover of legal education—is transforming our country. We're handing the reins of power to lawless radicals who will be America's future judges, prosecutors, politicians, and presidents. Unless we stop it now, the consequences will be with us for decades.

And the jacket blurbs:

Ilya Shapiro takes the academy to court—and wins. In this thoughtful new book, he makes the case that legal education has been captured and corrupted by left-wing ideologues. He knows it from observation, but also from experience. He pulls no punches and tells it like it is. — Christopher F. Rufo

When did breaking windows become an acceptable activity for lawyers-in-training? Lawless is the shocking story of how our most prestigious law schools were overtaken by student mobs, enabled by faculty and bureaucrats who care more about diversity quotas and "safety" than truth-seeking and the robust exchange of ideas. A sobering must-read. — William P. Barr

It should be axiomatic that the law is followed at law schools. But like much of what transpires on American campuses these days, it has become business as anything but usual. In Lawless, the brilliant Ilya Shapiro catalogues the ideological capture of America's law schools, where woke administrators and bureaucrats are focused on imposing their worldview and preferred social order, not on nurturing young minds to debate ideas freely and – yes – wrestle with opinions with which they don't agree. If debating ideas is too tough a task for aspiring lawyers, they certainly aren't ready for the courtroom, the boardroom, or anywhere else lawyers are required. — Betsy DeVos

I much look forward to Ilya's posts.

The post Ilya Shapiro Guest-Blogging About "Lawless: The Miseducation of America's Elites" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: January 12, 1932

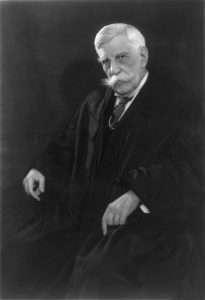

1/12/1932: Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes resigns from the Supreme Court.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes

Justice Oliver Wendell HolmesThe post Today in Supreme Court History: January 12, 1932 appeared first on Reason.com.

January 11, 2025

[Jonathan H. Adler] Another Study on Flavored Vaping Products the FDA Can Ignore

The Food and Drug Administration has been particularly resistant to approving the sale of vaping products that are not flavored like cigarettes. The vast majority of the vaping products approved to date have been tobacco flavored. A small handful, approved more recently, have been menthol flavored. The thousands of marketing applications for products with other flavors have been denied. Thus, there are no FDA-permitted vaping products on the market that provide consumers with a flavor different from that provided by cigarettes.

There is a growing body of evidence that restrictions on non-tobacco-flavored vaping products can increase smoking rates, including among youth. There is also growing evidence that non-tobacco-flavored vaping products may help smokers cut back on cigarette consumption or quit. Yet the FDA has shown little interest in this research, maintaining what appears to be a de facto ban on alternative vaping flavors.

A new peer-reviewed study in Addictive Behaviors provides additional evidence of that the availability of alternative flavors can help smokers reduce or cease their cigarette consumption. In this study, smokers were given vaping products with a choice of flavors with the aim of identifying "the impact of e-cigarette flavoring choice on e-cigarette uptake and changes in cigarette smoking." And what did it find?

Compared to participants who exclusively received the tobacco flavor, participants who received any other flavor combination had greater e-cigarette uptake at the end of product provision (74 % vs. 55 %), were more likely to reduce cigarette smoking by at least 50 % at the end of product provision (34 % vs. 14 %) and at the final 6-month follow up (29 % vs. 5 %), and numerically, but not statistically, more likely to be abstinent from cigarettes at the end of product provision (11 % vs. 5 %) and the final 6-month follow-up (14 % vs. 5 %).

From the paper:

Although only a small percentage of participants exclusively selected tobacco flavored e-cigarettes, the convergence of findings across multiple outcomes in this study suggest that non-tobacco flavors may be more appealing than tobacco flavors, and may better promote uptake and reduce cigarette smoking among adults who smoke. The FDA is currently issuing PMTA [premarket tobacco product application] decisions for individual e-cigarette products, and thus far, these decisions have included many MDOs [marketing denial orders] for non-tobacco flavors based on a lack of evidence that these flavors provide a benefit to adult smokers above and beyond the benefit provided by tobacco flavors. The data presented in this secondary analysis suggest that non-tobacco flavors may indeed provide a benefit to adults beyond the benefit provided by tobacco flavors, insofar as non-tobacco flavors better promote switching away from combustible cigarettes.

While this study is limited, it provides yet more evidence that the FDA's myopic approach to vaping product flavors may be undermining efforts to further reduce smoking and its associated public health consequences. It is also further evidence that the FDA's current approach to evaluating vaping product applications, and requiring those seeking approval of non-tobacco-flavored products to demonstrate that such products provide added benefits to public health as compared to tobacco-flavored products, is quite arbitrary. (And that this approach has been adopted without any sort of notice-and-comment process in which the FDA would have to defend this policy choice is just icing on the cake.)

The post Another Study on Flavored Vaping Products the FDA Can Ignore appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] N.H. Court Rejects Attempt to Impose Hate Crime Liability on Neo-Nazis for Hanging "Keep New England White" Sign on Overpass

From yesterday's N.H. Supreme Court decision in Attorney General v. Hood:

[According to the State's complaints,] a group of approximately ten people associated with NSC [National Socialist Club]-131, an unincorporated association that describes itself, in part, as a "pro-white, street-oriented fraternity dedicated to raising authentic resistance to the enemies of [its] people in the New England area," gathered on a highway overpass in Portsmouth. The group hung banners, one of which read "KEEP NEW ENGLAND WHITE," from the overpass.

Shortly thereafter, officers from the Portsmouth Police Department responded to the scene and informed Hood, whom they identified as the group's leader, that the group was violating a Portsmouth municipal ordinance that prohibited hanging banners from the overpass without a permit. Hood then instructed his associates to remove the banners from the overpass, although some individuals continued to display the banners by hand. The officers interacted with the group on the overpass for approximately twenty to twenty-five minutes before the group departed. NSC-131 subsequently took credit for the episode on social media.

The State filed complaints against the defendants seeking civil penalties and injunctive relief for their alleged violation of RSA 354-B:1. The State alleged that Hood and Cullinan violated and/or conspired to violate the Act when they led or aided a group of individuals to trespass upon the property of the State of New Hampshire and the City of Portsmouth by hanging banners reading "Keep New England White" from the overpass without a permit because their conduct was "motivated by race and interfered with the lawful activities of others." The State alleged that NSC-131 violated the Act when its members developed and executed a plan to commit the aforementioned act….

N.H. Stats. 354-B:1 provides,

All persons have the right to engage in lawful activities and to exercise and enjoy the rights secured by the [constitutions and laws] without being subject to actual or threatened physical force or violence against them or any other person or by actual or threatened damage to or trespass on property when such actual or threatened conduct is motivated by race, color, religion, national origin, ancestry, sexual orientation, sex, gender identity, or disability….

It shall be unlawful for any person to interfere or attempt to interfere with the rights secured by this chapter.

The court concluded that the state's interpretation of the Act as applying to defendants violated the New Hampshire Constitution's free speech provision:

[T]he State alleged that the defendants "trespassed upon the property of the State of New Hampshire and the City of Portsmouth when [they and other individuals] displayed banners reading 'Keep New England White' from the overpass without a permit." In objecting to Hood's motion to dismiss, the State argued that "[t]he defendant displayed a banner upon the fencing—causing a thing to enter upon land in possession of another, without any prior authorization from city or state authorities." Because the State alleged that the defendants intentionally invaded the property of another, and because "[t]he State, no less than a private owner of property, has power to preserve the property under its control for the use to which it is lawfully dedicated," we conclude that the State's complaints sufficiently alleged a civil trespass.

Nonetheless, we must next determine whether the State's proposed construction of the Act, applying the aforementioned definition of trespass, violates the defendants' constitutional rights to free speech…

Government property generally falls into three categories — traditional public forums, designated public forums, and limited public forums. Here, the trial court correctly reasoned that because "application of the Civil Rights Act requires no consideration of the relevant forum or the nature of the underlying regulations as to that forum," it applies "with equal force in traditional public fora as it does in limited or nonpublic fora." We agree with the trial court's assessment and proceed to the regulation at issue.

Government regulation of speech is content-based if a law applies to a particular type of speech because of the topic discussed or the idea or message expressed. The State argues that the Act "does not become a content or viewpoint-based action because the State relies upon a defendant's speech." Rather, it maintains that "[c]onsidering an actor's motivation to assess whether that remedy may be warranted has no impact on the person's right to freedom of speech, even when proof of motivation relies upon evidence of the person's speech, because a person's motivation has always been a proper consideration." We disagree.

The Act prohibits threatened and actual conduct only when "motivated by race, color, national origin, ancestry, sexual orientation, sex, gender identity, or disability." Thus, we agree with the trial court's assessment that "[b]ecause the Civil Rights Act's additional sanctions apply only where a speaker is 'motivated by race' or another protected characteristic, it is 'content-based' in that it 'applies to … particular speech because of the topic discussed or the idea or message expressed.'"

Content-based restrictions must be narrowly tailored to serve a compelling government interest. The State asserts that the requirement that a trespass be unprivileged or otherwise unlawful functions as a limitation sufficient to prevent its construction of the Act from being unconstitutionally overbroad. We are not persuaded. The trial court determined, and we agree, that although "prohibiting or discouraging interference with the lawful rights of others by way of bias-motivated conduct (including actual trespass) is a compelling government interest," the State's construction of the Act "is overly broad and not narrowly tailored to that end because, so construed, the Civil Rights Act applies in numerous circumstances which have no relation to this interest."

The following example used by the trial court illustrates this point.

For example, a person's disability rights protest at Veteran's Park in Manchester continuing after 11 p.m. may violate the [ordinance imposing a curfew] at issue in [State v. Bailey (N.H. 2014)], even if the protestor held a good faith belief that the regulation began at midnight or that there was no such curfew. Under the broader construction of the Civil Rights Act, the protestor will have violated [the Act] through their unprivileged presence on public property motivated by 'disability,' provided the protestor sufficiently 'interferes' with the lawful rights of others in doing so. Likewise, if the person were 'motivated by … sex' to be in Veteran's Park after 11 p.m. for reasons unrelated to any political protest, the person similarly will have violated the Civil Rights Act even if they were unaware of the curfew, provided there is a sufficient showing of 'interference.'

Although regulation of the defendants' banners may serve the compelling government interests of preventing interference or attempted interference with the rights secured by the Act, this example demonstrates that it is not narrowly tailored to do so. The overbreadth of the State's construction of the Act creates an unacceptable risk of a chill on speech protected by … our State Constitution….

Our conclusion is supported by considering the vagueness concerns raised by the trial court. As the trial court explained, "reading the trespass provision to include good faith, negligent trespass would fail to provide people of ordinary intelligence a reasonable opportunity to understand what conduct the Civil Rights Act prohibits." Furthermore, "[t]he absence of a 'knowing' mental state would charge the public with maintaining an actual, encyclopedic knowledge of a potentially limitless number of existing and future regulations governing all types of public fora on all government property before engaging in otherwise protected speech." We agree that such an expectation of citizens who enter public property is not reasonable.

The court held that the statute should instead be interpreted more narrowly:

We hold that, to state a claim for a violation of the Act predicated upon actual trespass on property, the State must establish that the actor, with knowledge that he or she is not licensed or privileged to do so, enters land in the possession of another or causes a thing or a third person to do so, and that the trespass was "motivated by race, color, religion, national origin, ancestry, sexual orientation, sex, gender identity, or disability." …

And the court held that, as so interpreted, the law didn't cover defendants:

The complaint against Hood alleged that he was not wearing a mask, "stepped forward and spoke with the officers," and identified himself as the group's leader. NSC-131 allegedly "took credit for the display of the banners" on its social media profiles. Furthermore, the group removed the banners from the overpass fence when they were apprised that they were trespassing on public property, and "[s]ome of [NSC-131's] members stood on the overpass and continued to display the banners by hand." Even when construing all reasonable inferences in the light most favorable to the State, we are not persuaded that the complaints sufficiently allege that the defendants knowingly trespassed.

This is an interesting analysis, but I'm not sure how it deals with the court's content discrimination objection: After all, under this analysis, the "disability rights protest … continuing after 11 p.m." that violates the park's nighttime closing rules may violate Rev. Stats. 354-B:1, so long as the protesters know that they are violating the rules, because it was "motivated by disability"—but, say, an anti-COVID-lockdown protest or environmentalist protest wouldn't be covered, because it wasn't "motivated by race, color, religion, national origin, ancestry, sexual orientation, sex, gender identity, or disability." What compelling interest would support that sort of content discrimination (and likely viewpoint discrimination)?

And beyond this, it's hard to see how even a knowingly ordinance-violating hanging of the banners here would interfere with persons' "right to engage in lawful activities and to exercise and enjoy [their] rights … without being subject to … trespass on property when such … conduct is motivated by race, color, [etc.]" However upsetting "Keep New England White" might have been to non-white residents, and even if the hanging of the banner was a trespass, they weren't made "subject to" the trespass in the normal sense of the phrase, I think: If you trespass on my property, that might make me "subject to" the trespass, but not if you trespass on the city's property.

Now the statute might make more sense, and might be constitutional, if it were interpreted to include the italicized added text below:

All persons have the right to engage in lawful activities and to exercise and enjoy the rights secured by the United States and New Hampshire Constitutions and the laws of the United States and New Hampshire without being subject to actual or threatened physical force or violence against them or any other person or by actual or threatened damage to or trespass on property when such actual or threatened conduct is motivated by those persons' race, color, religion, national origin, ancestry, sexual orientation, sex, gender identity, or disability.

This would basically be a law that forbids force, violence, or trespass targeting people because of those people's attributes, rather than because of the topic of a trespasser's speech (as in the disability rights protest). The Court has generally upheld such laws in Wisconsin v. Mitchell (1993), on the theory that they target not speech but the decision to select a crime victim based on the victim's attribute (much as, say, employment or public accommodations laws target decisions to treat someone worse because of their attributes).

If the law were read this way, it wouldn't apply to a disability rights protest that trespasses in a city park, whether or not the protesters knew they were trespassing, because they weren't trespassing in a way that was motivated by the victim's (the city's) disability. It would likewise not apply to a racist protest that trespasses on a city overpass—even knowingly trespasses—because the trespassers wouldn't be motivated by the victim's (the city's) race. On the other hand, the law would apply to someone protesting on a person's front lawn, or hanging a sign on the person's property, if the person was selected because he was disabled or black.

Alternatively, if the court believes that it can't read new words into a statute this way, and it thinks that the law therefore would cover knowingly trespassing disability rights protests in a city park—but wouldn't cover knowingly trespassing protests on other topics—then the law would have to be struck down as unconstitutional. But it seems to me that reading a knowing trespass requirement into the law just doesn't solve the First Amendment problem.

Bradford R. Stanton and William E. Gens (Gens & Stanton, P.C.) represent defendants. The ACLU of New Hampshire also filed a friend-of-the-court brief in support of defendants, which I think is generally consistent with the views I lay out above; an excerpt:

[The state's] interpretation of the Act would allow law enforcement officials to impose heightened "bias-motivated offense" penalties on anyone who trespasses while engaged in speech about race, religion, gender, or any other protected characteristic. In practice, that would mean that law enforcement officials have the power to impose heightened penalties any time someone commits even an inadvertent trespass while engaged in speech that the officials find offensive—whether the speech is by Black Lives Matter activists condemning racism by white people, pro-Palestine activists protesting the war in Gaza, or pro-Israel proponents counterprotesting. Neither the First Amendment nor the Act's legislative history support such a dramatic expansion of the Act's scope….

[T]his Court should hold RSA 354-B:1 does not apply to trespasses on public property motivated by the desire to express a message related to protected characteristics where there is no evidence of discriminatory targeting. Alternatively, this Court should hold that RSA 354-B:1 is unconstitutional applied to the facts alleged in the Complaints.

The post N.H. Court Rejects Attempt to Impose Hate Crime Liability on Neo-Nazis for Hanging "Keep New England White" Sign on Overpass appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: January 11, 1830

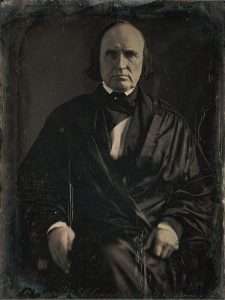

1/11/1830: Justice John McLean takes oath.

Justice John McLean

Justice John McLean

The post Today in Supreme Court History: January 11, 1830 appeared first on Reason.com.

January 10, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Friday Open Thread

The post Friday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Attorneys May Have to Ask Expert Witnesses "Whether They Have Used AI in Drafting Their Declarations and What They Have Done to Verify Any AI-Generated Content"

From Kohls v. Ellison, which I quoted more extensively in an earlier post:

To be sure, Attorney General Ellison maintains that his office had no idea that Professor Hancock's declaration included fake citations, and counsel for the Attorney General sincerely apologized at oral argument for the unintentional fake citations in the Hancock Declaration. The Court takes Attorney General Ellison at his word and appreciates his candor in rectifying the issue.

But Attorney General Ellison's attorneys are reminded that Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 11 imposes a "personal, nondelegable responsibility" to "validate the truth and legal reasonableness of the papers filed" in an action. The Court suggests that an "inquiry reasonable under the circumstances," Fed. R. Civ. P. 11(b), may now require attorneys to ask their witnesses whether they have used AI in drafting their declarations and what they have done to verify any AI-generated content.

Thanks to Prof. Anthony Bushnell for pointing out the significance of this particular passage.

The post Attorneys May Have to Ask Expert Witnesses "Whether They Have Used AI in Drafting Their Declarations and What They Have Done to Verify Any AI-Generated Content" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Misinformation Expert's "Citation to Fake, AI-Generated Sources in His Declaration … Shatters His Credibility with This Court"

From today's order by Laura Provinzino (D. Minn.) in Kohls v. Ellison (see this Nov. 19 post for more):

Minnesota law prohibits, under certain circumstances, the dissemination of "deepfakes" with the intent to injure a political candidate or influence the result of an election. Plaintiffs challenge the statute on First Amendment grounds and seek preliminary injunctive relief prohibiting its enforcement.

With his responsive memorandum in opposition to Plaintiffs' preliminary-injunction motion, Attorney General Ellison submitted two expert declarations … [including one] from Jeff Hancock, Professor of Communication at Stanford University and Director of the Stanford Social Media Lab. The declarations generally offer background about artificial intelligence ("AI"), deepfakes, and the dangers of deepfakes to free speech and democracy….

Attorney General Ellison concedes that Professor Hancock included citations to two non-existent academic articles and incorrectly cited the authors of a third article. Professor Hancock admits that he used GPT-4o to assist him in drafting his declaration but, in reviewing the declaration, failed to discern that GPT-4o generated fake citations to academic articles.

The irony. Professor Hancock, a credentialed expert on the dangers of AI and misinformation, has fallen victim to the siren call of relying too heavily on AI—in a case that revolves around the dangers of AI, no less. Professor Hancock offers a detailed explanation of his drafting process to explain precisely how and why these AI-hallucinated citations in his declaration came to be. And he assures the Court that he stands by the substantive propositions in his declaration, even those that are supported by fake citations. But, at the end of the day, even if the errors were an innocent mistake, and even if the propositions are substantively accurate, the fact remains that Professor Hancock submitted a declaration made under penalty of perjury with fake citations.

It is particularly troubling to the Court that Professor Hancock typically validates citations with a reference software when he writes academic articles but did not do so when submitting the Hancock Declaration as part of Minnesota's legal filing. One would expect that greater attention would be paid to a document submitted under penalty of perjury than academic articles. Indeed, the Court would expect greater diligence from attorneys, let alone an expert in AI misinformation at one of the country's most renowned academic institutions.

To be clear, the Court does not fault Professor Hancock for using AI for research purposes. AI, in many ways, has the potential to revolutionize legal practice for the better. See Damien Riehl, AI + MSBA: Building Minnesota's Legal Future, 81-Oct. Bench & Bar of Minn. 26, 30–31 (2024) (describing the Minnesota State Bar Association's efforts to explore how AI can improve access to justice and the quality of legal representation). But when attorneys and experts abdicate their independent judgment and critical thinking skills in favor of ready-made, AI-generated answers, the quality of our legal profession and the Court's decisional process suffer.

The Court thus adds its voice to a growing chorus of courts around the country declaring the same message: verify AI-generated content in legal submissions! See Mata v. Avianca, Inc., 678 F. Supp. 3d 443, 466 (S.D.N.Y. 2023) (sanctioning attorney for including fake, AI-generated legal citations in a filing); Park v. Kim, 91 F.4th 610, 614–16 (2d Cir. 2023) (referring attorney for potential discipline for including fake, AI-generated legal citations in a filing); Kruse v. Karlan, 692 S.W.3d 43, 53 (Mo. Ct. App. 2024) (dismissing appeal because litigant filed a brief with multiple fake, AI-generated legal citations).

To be sure, Attorney General Ellison maintains that his office had no idea that Professor Hancock's declaration included fake citations, and counsel for the Attorney General sincerely apologized at oral argument for the unintentional fake citations in the Hancock Declaration. The Court takes Attorney General Ellison at his word and appreciates his candor in rectifying the issue. But Attorney General Ellison's attorneys are reminded that Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 11 imposes a "personal, nondelegable responsibility" to "validate the truth and legal reasonableness of the papers filed" in an action. The Court suggests that an "inquiry reasonable under the circumstances," Fed. R. Civ. P. 11(b), may now require attorneys to ask their witnesses whether they have used AI in drafting their declarations and what they have done to verify any AI-generated content.

The question, then, is what to do about the Hancock Declaration. Attorney General Ellison moves for leave to file an amended version of the Hancock Declaration, and argues that the Court may still rely on the amended Hancock Declaration in ruling on Plaintiffs' preliminary-injunction motion. Plaintiffs seem to accept that Professor Hancock is qualified to render an expert opinion on AI and deepfakes, and the Court does not dispute that conclusion. Nevertheless, Plaintiffs argue that the Hancock Declaration should be excluded in its entirety and that the Court should not consider an amended declaration. The Court agrees.

Professor Hancock's citation to fake, AI-generated sources in his declaration—even with his helpful, thorough, and plausible explanation—shatters his credibility with this Court. At a minimum, expert testimony is supposed to be reliable. More fundamentally, signing a declaration under penalty of perjury is not a mere formality; rather, it "alert[s] declarants to the gravity of their undertaking and thereby have a meaningful effect on truth- telling and reliability." The Court should be able to trust the "indicia of truthfulness" that declarations made under penalty of perjury carry, but that trust was broken here.

Moreover, citing to fake sources imposes many harms, including "wasting the opposing party's time and money, the Court's time and resources, and reputational harms to the legal system (to name a few)." Morgan v. Cmty. Against Violence, 2023 WL 6976510, at *8 (D.N.M. Oct. 23, 2023). Courts therefore do not, and should not, "make allowances for a [party] who cites to fake, nonexistent, misleading authorities"—particularly in a document submitted under penalty of perjury. Dukuray v. Experian Info. Sols., 2024 WL 3812259, at *11 (S.D.N.Y. July 26, 2024). The consequences of citing fake, AI- generated sources for attorneys and litigants are steep. See Mata; Park; Kruse. Those consequences should be no different for an expert offering testimony to assist the Court under penalty of perjury.

To be sure, the Court does not believe that Professor Hancock intentionally cited to fake sources, and the Court commends Professor Hancock and Attorney General Ellison for promptly conceding and addressing the errors in the Hancock Declaration. But the Court cannot accept false statements—innocent or not—in an expert's declaration submitted under penalty of perjury. Accordingly, given that the Hancock Declaration's errors undermine its competence and credibility, the Court will exclude consideration of Professor Hancock's expert testimony in deciding Plaintiffs' preliminary-injunction motion.

The post Misinformation Expert's "Citation to Fake, AI-Generated Sources in His Declaration … Shatters His Credibility with This Court" appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers