Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 160

February 21, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Judge Ho's Decision To Appoint Paul Clement In United States v. Adams (Updated)

[This decision may not pan out for the court.]

Today, Judge Ho (no, not that Judge Ho) appointed Paul Clement as an amicus in United States v. Adams.

Accordingly, to assist with its decision-making via an adversarial process, the Court exercises its inherent authority to appoint Paul Clement of Clement & Murphy PLLC as amicus curiae to present arguments on the Government's Motion to Dismiss. See Seila L. LLC v. Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, 591 U.S. 197, 209 (2020) ("Because the Government agrees with petitioner on the merits of the constitutional question, we appointed Paul Clement to defend the judgment below as amicus curiae. He has ably discharged his responsibilities.") . The Court expresses its gratitude to Mr. Clement for his service and will provide Mr. Clement a copy of this Order and the transcript from the February 19 conference.

From time-to-time, the federal government declines to defend a judgment in a pending Supreme Court case. In such cases, the Court will appoint an amicus to defend the judgment below. In other words, the amicus is not arguing his own personal views on the law, but is instead defending what the lower court did.

This approach makes some sense when there is an actual lower-court opinion. But this approach does not make sense in a trial court. The Court appointed Paul Clement to "present arguments on the Government's Motion to Dismiss." What kind of arguments? The order does not say. Maybe Clement will agree with the government. Maybe he won't. Who knows? In effect, the Court has appointed Paul Clement to give Paul Clement's opinion on the issue. Clement is a friend of the Court, to be sure. But unlike most amicus, he is being elevated to the status of a party. I think Article III jurisdiction demands adversity, and appointing an amicus to argue his own views does not suffice for adversity. For all we know, Clement will agree with the government, and there still will be no adversity.

In candor, I am a bit befuddled by this decision. I know Judge Sullivan appointed an amicus in the Michael Flynn case. That is certainly a precedent, but not a particularly good one.

There is another element to discuss here. It is pretty obvious the Court appointed Clement to have a well-known conservative (potentially) argue against the Trump Administration. Judge Ho took a page from the Seila Law playbook, in which Circuit Justice Kagan selected Clement. I described Kagan's choice back in 2020:

That choice fell to Justice Kagan, the Circuit Justice for the Ninth Circuit. And she made a strategic decision. Rather than selecting someone like Deepak Gupta, a steadfast defender (and former employee) of the CFPB, she looked to the right, and picked Paul Clement. Yes, she selected the former Scalia clerk who (I suspect) agrees with fellow Scalia clerks, SG Francisco and Kannon Shanmugam.

At the time, I thought it was a shrewd move. Clement would be better served to hand-craft arguments for the conservatives on the bench, particularly Chief Justice Roberts, who may otherwise be inclined to rule against the CFPB. In effect, Kagan chose Clement as the equivalent of a counter-clerk. (I am not sure if Kagan has adopted the sometimes-practice of Justice Scalia, and picked counter-clerks for her own chambers).

Did Kagan's choice pan out? I do not think it did. You can read what I wrote in 2020, which I know caused some controversy at the time. Lawyers are trained to zealously argue in favor of a client. But Clement has no client here.

Will Clement's appointment here work out for Judge Ho? Well, unlike with Seila Law, Clement is not forced to defend any particular judgment. He will give his own opinion. And I have to think that Judge Ho did not inquire about those views in advance. If he did, that would be extremely problematic.

Ultimately, I think this entire exercise is a waste of time. The Judge should dismiss the prosecution promptly. This appointment simply reaffirms the perception of how Lawfare continues to hobble the Trump Administration. Indeed, DOJ is trying to de-weaponize the law by dismissing an indictment. But it cannot do so.

Update: Maybe we can predict what Clement might say in this case. As some readers may know, Paul Clement represented Boeing before the Fifth Circuit. Boeing and the United States reached a deferred prosecution agreement, which would have effectively dismissed the prosecution. Co-blogger, Paul Cassell represented the family members of victims of Boeing crash, who objected to the deal. Clement's brief to the Fifth Circuit speaks about the importance of the Prosecutor's ability to dismiss cases:

The Constitution entrusts the Executive—and the Executive alone—with the duty to "take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed." U.S. Const. art. II, §3. Given that constitutional command, it is unsurprising that "[t]he Executive's primacy in criminal charging decisions is long settled," as "decisions to initiate charges, or to dismiss charges once brought, lie at the core of the Executive's duty to see to the faithful execution of the laws." Fokker, 818 F.3d at 741 (alterations omitted); see, e.g., United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683, 693 (1974) ("[T]he Executive Branch has exclusive authority and absolute discretion to decide whether to prosecute a case[.]"). Conversely, judicial authority is "at its most limited" when reviewing a prosecutor's exercise of discretion over charging decisions, as "few subjects are less adapted to judicial review than the exercise by the Executive of his discretion in deciding when and whether to institute criminal proceedings, or what precise charge shall be made, or whether to dismiss a proceeding once brought." Fokker, 818 F.3d at 741; see Wayte v. United States, 470 U.S. 598, 607 (1985) ("[T]he decision to prosecute is particularly ill-suited to judicial review."). While several other countries have systems in which courts have a direct role in initiating or supervising criminal prosecutions, that is decidedly not the system the Framers adopted. See Blakely v. Washington, 542 U.S. 296, 313 (2004). Our Constitution leaves it to prosecutors, not courts, to decide whether and how to pursue or dismiss criminal charges. As the Second and D.C. Circuits have recognized, those principles preclude district courts from superintending the quintessentially prosecutorial decisions embodied in DPAs.

Clement also represents Attorney General Drummond in Glossip v. Oklahoma. The entire premise of that case is that the Attorney General, and not the Court, decides whether a prosecution goes forward. Those facts are not exactly analogous to the Adams context, but they are consistent with what Clement argued in the Boeing case.

Anyway, if I was looking to appoint a lawyer who has filed arguments in support of Emile Bove's position, then Paul Clement would be my pick. I do not know if Judge Ho was aware of these cases.

The post Judge Ho's Decision To Appoint Paul Clement In United States v. Adams (Updated) appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Defamation/Impersonation Campaign as RICO Violation (with $9M in RICO Trebled Damages)

My sense is that such claims are often made but nearly never win—yet here they did. From Hartman v. Does 1-2, decided earlier this month, Eleventh Circuit Judges Adalberto Jordan, Robin Rosenbaum, and Barbara Lagoa upheld a $12.5M verdict (including $9M under RICO) in such a case:

In this action, Plaintiffs-Appellees real-estate professional Jason Hartman and his companies accused Defendants—a rival real estate investor and his associates—of committing a wide variety of misconduct as part of a smear campaign to harm Plaintiffs' reputation and steal their clients. The allegations asserted federal and state RICO violations, false advertising, invasion of privacy, trademark infringement, and unfair competition. The case proceeded to trial, and the jury returned a verdict for Plaintiffs and awarded substantial damages, including for counts on which the court had already determined liability at summary judgment….

Hartman is a real-estate investment professional and podcaster who formed two companies, Platinum Properties Investor Network Inc. and The Hartman Media Company LLC, to promote real estate investment through his investor network. Hartman Media owns the valid, registered service marks "Jason Hartman" and "jasonhartman.com."

Charles Sells ("Sells") owned and operated a competing real-estate investment advisory company, the PIP Group, LLC, along with his wife, Elena Sells ("Lena"), PIP's director of operations and 49% owner.

In 2018, Hartman's businesses were on a "steady upward trajectory," earning a spot on Inc. Magazine's list of the 5,000 fasting growing companies. Sells, meanwhile, was trying to combat negative online reviews of PIP, which he blamed in part on Hartman, who previously had invested in and was openly critical of PIP's tax-lien investment business. Sells was convinced that Hartman was behind some negative reviews, though Sells admitted at trial he had no evidence to support those claims. Sells and Hartman were also involved in separate litigation.

In May 2018, Sells began a smear campaign against Hartman, intending to "crush[ ] this douche" and "put[ ] him out of business completely." Sells testified that his goal was not only to destroy Hartman's business, but also to destroy him personally and emotionally. To accomplish these goals, Sells set out to create a "very documented, very exposing website" to disseminate negative information about Hartman and his companies. For the "technical side" of things, he relied on Young Chung, the founder of digital marketing agency Blindspot Digital, whom Sells had hired to improve PIP's own website a few months earlier. With Chung's help, Sells registered multiple online domain names that were confusingly similar to Hartman's name or his companies, so that they would show up on internet searches for Hartman. Chung then built a website hosted on the domain "jasonhartmanproperties.com," where the other [similarly named] domains Sells bought redirected. Sells used offshore entities and false contact information to register the domains and host the jasonhartmanproperties.com website. And he created content for the site with assistance from Stephanie Putich, PIP's sales and marketing coordinator.

After the jasonhartmanproperties.com website went live at the end of May 2018, Sells, Chung, and Putich distributed links to the site, at times using fake names, via internet forums, social media, and emails. At Sells's direction, Chung and Putich compiled a contact list of anyone with potential connections to Hartman to send email "blasts" with negative information about Hartman and a link to the website. Many of the emails purported to be from Hartman at the email address jasonhartman@protonmail.com, which was created by Sells using false contact information.

The emails and website contained false and misleading statements of material fact relating to Hartman's businesses, financial history, litigation history, commercial dealings, alleged prurient nature, credibility, and trustworthiness. When Hartman took action to have the jasonhartman@protonmail.com account and jasonhartmanproperties.com website shut down for infringement, Sells tasked Chung and Putich with transferring the contents of the website to a new domain, www.thebrokeguru.com, and hiding any connections. Once the transfer was complete, Sells sent additional rounds of emails and links to the new "Broke Guru" website, which contained essentially the same false and misleading statements as the original website, as well as links to PIP's own website. The Broke Guru website remained active until August 2019.

During the fiscal year from 2018 to 2019, the gross revenue of Hartman's companies, Hartman Media and Platinum Properties, collectively fell more than 40%. Consistent with that drop off, Hartman testified that due to the smear campaign, he lost speaking gigs at conferences and former clients stopped communicating. In addition, some clients used the scheme's false information as leverage to renegotiate deals, and others simply refused payment. Over the same period, PIP's gross revenue nearly doubled. Sells was aware of the positive effect on PIP's business. For instance, a June 2018 email from Sells to Putich noted that, while the scheme against Hartman was not "a savory project," it was "already helping us tremendously" in marketing.

Plaintiffs sued under various claims, and "the district court granted summary judgment [for plaintiffs] as to liability … [as to] federal service-mark counterfeiting[,] … federal cybersquatting[,] … federal unfair competition and false designation of origin[,] and common-law unfair competition through use of Plaintiffs' service marks." The jury also found for plaintiffs as to "false advertising under federal and Florida law" and "Florida civil conspiracy and invasion of privacy," as well as RICO violations." Plaintiffs were awarded $9M under RICO (the jury $3M verdict trebled), plus $3M+$500K punitives as to invasion of privacy.

Regarding the RICO claims, Plaintiffs argued to the jury that Defendants' "predicate acts" of racketeering activity included wire fraud, knowingly using a counterfeit service mark, and retaliating against Hartman for notifying police of the possible commission of a federal offense. In particular, according to Plaintiffs' theory of the case, Defendants committed mail fraud "[e]very time they sen[t] out an e-mail blast," "disseminat[ed] this out on websites," or lied to service providers to obtain access to services, so there were "hundreds of instances of wire fraud" before the jury.

The Eleventh Circuit rejected defendants' various objections, but noted that "Defendants have not developed any argument specific to the predicate acts, such as mail fraud, or to the other elements of the RICO claims. We express and imply no opinion as to whether the evidence was otherwise sufficient to satisfy those elements."

Ryan Santurri, Ava K. Doppelt, Brian R. Gilchrist (Allen Dyer Doppelt & Gilchrist, PA), Jeffrey E. Grell (Grell Feist PLC), and Steven Pollack (Pollack Law, PC) represent plaintiffs.

The post Defamation/Impersonation Campaign as RICO Violation (with $9M in RICO Trebled Damages) appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: February 21, 1868

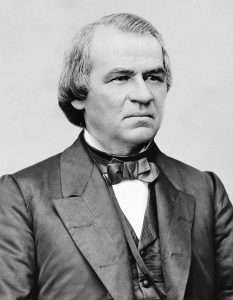

2/21/1868: President Johnson orders Secretary of War Edwin Stanton removed from office. In Myers v. U.S. (1926), the Supreme Court found that Johnson's actions were lawful.

President Andrew Johnson

President Andrew JohnsonThe post Today in Supreme Court History: February 21, 1868 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Friday Open Thread

The post Friday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

February 20, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] States Have Standing to Challenge Regulations Requiring Them to Reasonably Accommodate Employees Who Seek Abortions

From today's decision in Tennessee v. EEOC, decided by Eighth Circuit Chief Judge Steven Colloton, joined by Judges James Loken and Jonathan Kobes:

Tennessee and sixteen other states brought this action to challenge the lawfulness of a regulation promulgated by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The States moved for a preliminary injunction. The district court concluded that the States lacked standing to sue and dismissed the action for lack of jurisdiction. The States appeal, and we reverse and remand….

Congress enacted the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000gg, in 2022. The Act declares it unlawful for a covered employer to "not make reasonable accommodations to the known limitations related to the pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions of a qualified employee," absent a showing of undue hardship to the employer. The statute defines a "known limitation" as a "physical or mental condition related to, affected by, or arising out of pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions." The Act applies to state and local governments as employers, and Congress declared that a State shall not be immune under the Eleventh Amendment from an action for a violation of the Act.

Congress tasked the EEOC to issue regulations to implement the Act. After notice and comment, the EEOC promulgated 29 C.F.R. § 1636, a final rule implementing the Act. Among its provisions, the Rule provides an extensive list of example conditions that "are, or may be, 'related medical conditions'" under the Act's definition of "known limitation."

The list includes "termination of pregnancy, including via miscarriage, stillbirth, or abortion." "Reasonable accommodation" varies with the employee's condition and circumstances but generally includes adjustments to work environment, job restructuring, unpaid leave, and the ability to use accrued paid leave. In addition to the cost of providing any given accommodation, the EEOC expects regulated parties to experience one-time administrative compliance costs from such activities as familiarizing themselves with the rules, posting new EEO posters, and updating employment policies and handbooks.

The States believe that the Rule requires them to make reasonable accommodations for state employees seeking an abortion in all circumstances. The States currently refuse to accommodate state employees who seek elective abortions. Different States have different policies about when an abortion is elective, but all of the state policies conflict with the Rule.

The States sued the EEOC seeking an injunction against enforcement of the Rule and a declaratory judgment that the Rule is unlawful. The States advanced four grounds for relief: (1) the Rule is arbitrary and capricious; (2) the agency's definition of "related medical conditions" exceeds the EEOC's authority under the Act; (3) the Rule violates the First Amendment and constitutional principles of federalism; and (4) the EEOC's for-cause removal structure is unconstitutional under Article II of the Constitution.

Without reaching the merits of these claims, the district court dismissed the action for lack of jurisdiction. The court concluded that there was no case or controversy under Article III because the States failed to allege an injury in fact that could establish standing to challenge the Rule.

The court concluded that the States' alleged sovereign harms were not imminent because the risk of enforcement is speculative. The court also ruled that any sovereign injury was not redressable by the court because a decision setting aside the Rule would not eliminate the possibility that the Act by itself requires the States to accommodate employees who seek elective abortions.

The court next concluded that the costs of complying with the Rule did not establish an injury in fact. The court reasoned that the States could not trace any definite portion of expected one-time compliance costs to the challenged portion of the Rule and that the costs of providing accommodations are not traceable to a threat of enforcement.

Finally, the court rejected the argument that the States have standing by virtue of their position as direct objects of the EEOC's regulatory action. The district court dismissed the motion for preliminary injunction as moot and, in the alternative, because the States failed to show irreparable harm….

We conclude that the States have standing to challenge the Rule. The States are the object of the EEOC's regulatory action. They are employers covered by the Act and the Rule. The States allege that the Rule compels them to provide accommodations to employees that the States otherwise would not provide, to change their employment practices and policies, and to refrain from pro-life messaging that arguably would be "coercive" and thus proscribed by the Rule. Because the States are the object of an agency action, they are injured by the imposition of new regulatory obligations. The injury is caused by the agency's action, and a judicial decision setting aside the action would remedy the injury.

The imposition of a regulatory burden itself causes injury. In West Virginia v. EPA (2022), the Supreme Court held that the plaintiff States were injured by an EPA regulation because they were "'the object of' its requirement that they more stringently regulate power plant emissions within their borders." The Court thus deemed it unnecessary to consider whether the requirement caused any specific economic harms to the States or whether the States faced a credible threat of enforcement if they refused to comply. This court similarly held that an association of cities alleging that an agency action violated its procedural rights had standing to challenge the action because the cities had a concrete interest in avoiding regulatory obligations that were not authorized by statute.

The EEOC maintains that the Rule does not compel the States to act and does not produce an injury until an employee requests an abortion-related accommodation. Although the EEOC anticipates that employers will update employment policies and train their staffs on new requirements, the EEOC contends that these are voluntary measures not required by the Rule.

The agency's notion of actions undertaken "voluntarily" is inconsistent with the realities facing these regulated parties. Covered entities must comply with the Rule, and we presume that the States will follow the law as long as the Rule is in effect. An employer cannot meet its obligations under the Rule without taking steps to ensure that its employees know their rights and obligations under the Rule. As a practical matter, the Rule requires immediate action by the States to conform to the Rule, and this action produces an injury in fact.

The EEOC argues that any injury is too speculative under School of the Ozarks, Inc. v. Biden (8th Cir. 2022). In School of the Ozarks, however, an institution of higher education sought to challenge a federal agency's internal memorandum that did not regulate the college. The memorandum merely gave direction to agency staff and did not injure the institution. By contrast, the States in this case are the direct objects of the EEOC's rule, and the Rule injures the States by requiring them to act contrary to their established policies.

For these reasons, we conclude that the States have Article III standing to sue, and we therefore reverse the judgment dismissing the action. We remand the case for further proceedings and express no view on the merits of the claims….

Whitney D. Hermandorfer of the Tennessee Attorney General's Office argued on behalf of the states.

The post States Have Standing to Challenge Regulations Requiring Them to Reasonably Accommodate Employees Who Seek Abortions appeared first on Reason.com.

[Paul Cassell] The Crime Victims' Rights Movement's Past, Present, and Future (Part III - the Future)

[Efforts to expand and amplify victims' voices in criminal proceedings are justified and likely to continue into the future.]

This is the third and concluding post serializing my comprehensive law review article on the past, present, and future of the crime victims' rights movement. Earlier I blogged about the movement's past and present. In this post, I look to the future. The movement seems likely to push for—and achieve—additional measures for asserting and enforcing victims' rights. And it is time for the movement to renew its advocacy for a federal constitutional amendment protecting victims' rights.

Back in 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court stated in expansive dicta that "in American jurisprudence at least, a private citizen lacks a judicially cognizable interest in the prosecution or nonprosecution of another." (Linda R.S v. Richard D., 410 U.S. 614.) Whatever the validity of that conclusion in 1973, more than a half-century later it is no longer correct. Even at the time, the Court's conclusion ignored this country's long history of private prosecution, with victims directing and even initiating criminal prosecutions. And in the last several decades, the crime victims' rights movement has created specific victims' interests in criminal prosecutions, with victims' bills of rights and other enactments giving victims a clear right to participation.

Today the public demands that victims play an important role in criminal justice processes. This view was well described in a Justice Department report regarding victims' rights: "When a person is harmed by a criminal act, the agencies that make up our criminal and juvenile justice systems have a moral and legal obligation to respond. It is their responsibility not only to seek swift justice for victims but to ease their suffering in a time of great need."

Exactly how the criminal justice system should respond to crime victims and their suffering remains a work in progress, with differences evident from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. But the basic contours of these responses are similar—as captured in a "victim participation model" first described by law professor Douglas Beloof. Today, the criminal justice processes in the federal system and all fifty states extend rights to crime victims, although the enforcement of these rights varies. Generally speaking, for felony and other important criminal cases, crime victims can be heard at appropriate points in the process, most commonly at sentencing through victim impact statements. Victims also are generally entitled to notice of court proceedings and to be able to attend court proceedings. Victims are also frequently given the right to confer with prosecutors and can sometimes shape a prosecutor's decision to file (or not file) criminal charges. Thus, victims now possess the right to participate in the criminal justice process.

These participatory rights are described in Beloof's victim participation model, which helps to reveal the fallacy in equating the crime victims' rights movement with crime control issues. No doubt, the movement's critics can point to examples of victims' advocates pressing for punitive measures that may (or may not) be excessive. But these efforts are not properly categorized as part of the modern victims' rights agenda. Instead, as clarified by Beloof's third model—the victim participation model—these efforts would best be described as part of a separate crime control agenda (as captured in Professor Packer's famous crime control vs. due process models). As Beloof explains, the victim participation model recognizes each victim as an individual and allows that individual's voice to be heard. But whether to be heard—that is, whether to participate and exercise rights—is left to each individual victim. And what the victim says is likewise left to the individual victim. For example, the victim may seek a punitive sentence or a lenient one. But the point of the crime victims' rights movement is that the victim is heard, not that the victim achieves a punitive or merciful objective. It is for this reason that mandatory minimum sentences are not part of the victims' rights movement's agenda.

Against the backdrop of the advances in victims' rights, victims will undoubtedly continue to play an important role in American criminal justice proceedings in the future. But it is interesting to consider how the victim's role might continue to evolve. As I explain at length in my article, the victims' rights movement will, no doubt, work to shore up weaknesses in existing victims' rights regimes. And in considering the future trajectory of crime victims' rights, further expansion of victims' rights seems most likely—and is easiest to justify—where two conditions exist: first, where victims' claims will not interfere with recognized and legitimate interests of criminal defendants; and, second, where the cost is not prohibitive. If so, the future will likely bring significant expansions of crime victims' rights. Victims' rights do not generally interfere with defendant's rights. And victims' rights are generally not extremely costly.

Regarding potentially harming defendant's interests, the bulk of the victims' rights agenda seeks procedural protection of victims' rights to be heard—to have a "voice, not a veto." Victims can be given a voice without harming the rights of criminal defendants. The victims' movement has not pushed for giving victims a voice in trials, focusing on other proceedings. And defendants do not have a legitimate interest in silencing victims in these other proceedings. For example, at sentencing, it has long been the law that a judge is free to consider all information that might have some bearing on the appropriate sentence.

In the 1990s, a federal victims' rights amendment to the U.S. Constitution was under consideration—and supported by some strong defenders of defendants' rights. Harvard law professor Laurence Tribe, for example, joined me in concluding that the proposed federal victims' rights amendment would "add[] victims' rights that can coexist side by side with defendants.'"

Most victims' rights initiative are largely cost-free, as they simply involve allow victims to participate in existing processes. But the future seems likely to bring attention to one important area where crime victims' rights could impose at least some modest costs: the victim's right to legal counsel. In America today, a serious obstacle to victims' rights enforcement, even in states with strong victims' rights protections, is the difficulty victims have in securing legal counsel. Ever since the Supreme Court's 1963 decision in Gideon v. Wainwright, indigent criminal defendants have been promised legal assistance. In contrast, crime victims are generally not provided legal counsel at state expense. Indeed, many state enactments specifically exclude such a possibility, presumably because of political compromises by victims' advocates to move victims' enactments forward. The issue of providing at least some victims' legal counsel to help with pressing legal issues needs to be revisited.

Other significant targets for improving victims' rights also exist, particularly in the area of enforcing victims' rights. While Marsy's Law and other state efforts have helped to improve the enforcement of crime victims' rights, those efforts have not comprehensively guaranteed protections for crime victims. Of course, the current landscape of victims' rights in the United States—which occurs against the backdrop of federalism and varying state practices—is a patchwork quilt. Some states have effective regimes in place, while others do not. It continues to be straightforward to find examples of victims who are unable to enforce their rights in state (and federal) criminal processes.

As a result, the victims' rights movement seems likely to seek—and should seek—one overarching goal: a federal victims' rights amendment. Since first proposed by the President's Task Force in 1982, a federal amendment has remained the movement's greatest objective. Even though considerable progress has been made in the last several decades toward improving victims' rights, that progress has been uneven and incomplete. As a recent analysis concluded, crime victims' rights are too often underenforced, "due mainly to the lack of effective implementation of victims' rights laws. Issues such as the lack of professional knowledge, the lack of enforcement mechanisms, strict eligibility criteria for compensation, existence of varying definitions of victim across jurisdictions, and the limited scope of most crime victim legislations, all undermine the effort to protect victims successfully and achieve a global recognition of the status of victims in the criminal justice system."

In one fell swoop, a federal constitutional amendment would not only achieve "global recognition" of victims but also respond to many of the problems that currently hamper victims' rights efforts. As I have argued elsewhere, the values undergirding a federal amendment "are widely shared in our country, reflecting a strong consensus that victims' rights should receive protection. Contrary to the claims that a constitutional amendment is somehow unnecessary, practical experience demonstrates that only federal constitutional protection will overcome the institutional resistance to recognizing victims' interests. And while some have argued that victims' rights do not belong in the Constitution, in fact a victims' rights amendment would addresses subjects that have long been considered entirely appropriate for constitutional treatment."

Using state constitutional amendments as models for language, it is possible to carefully draft a federal amendment so as to protect victims' interests in the system without harming defendants' and others' interests. Congress last held hearings on the amendment in 2013 and 2015. With the increasing success of the victims' rights movement in advancing state constitutional amendments, it is time for the movement to make a new push for a comprehensive federal amendment.

If you have found my series of posts interesting, you can read my entire article on the victims' rights movement here. Tomorrow, I will be presenting the article at a symposium hosted by the University of Pacific Law Review -- which will be live-streamed here, starting at 8:30 a.m. Pacific time.

The post The Crime Victims' Rights Movement's Past, Present, and Future (Part III - the Future) appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Ninth Circuit Denies Government Request for Emergency Relief in Birthright Citizenship Case

[The first of what may be many appellate rulings on the Trump Administration's most controversial and questionable Executive Order.]

Yesterday, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit denied the Trump Administration's request for emergency relief in Washington v. Trump, one of the cases challenging the Trump Administration's Executive Order purporting to narrow and redefine birthright citizenship. Specifically, the Trump Administration sought a partial stay of the preliminary injunction against acting on the Executive Order entered by the district court. The panel of Judges Canby, M. Smith, and Forrest denied the motion, stating simply that the Administration had "not made a 'strong showing that [they are] likely to succeed on the merits' of this appeal."

Judge Forrest (incidentally a Trump appointee) wrote a separate concurring opinion, explaining her reasons for denying the motion. It is reproduced below.

The Government has presented its motion for a stay pending appeal on an emergency basis, asserting that it needs the relief it seeks by February 20. Thus, the first question that we must ask in resolving this motion is whether there is an emergency that requires an immediate answer.

Granting relief on an emergency basis is the exception, not the rule. Cf. Nken v. Holder, 556 U.S. 418, 427 (2009) (noting that a non-emergency stay "is an 'intrusion into the ordinary processes of administration and judicial review,' and accordingly 'is not a matter of right, even if irreparable injury might otherwise result to the appellant.'" (citations omitted)); Labrador v. Poe ex rel. Poe, 144 S. Ct. 921, 934–35 (2024) (mem.) (Jackson, J., dissenting from grant of stay) ("Even when an applicant establishes [the] highly unusual line-jumping justification [for a nonemergency stay], we still must weigh the serious dangers of making consequential decisions 'on a short fuse without benefit of full briefing and oral argument.'" (citations omitted)). Neither the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure nor the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure address what a party must show to warrant immediate equitable relief. Cf. Fed. R. Civ. P. 62(g)(1); Fed. R. App. P. 8(a)(2)(D); Fed. R. App. P. 27(c). Nor do the "traditional" stay factors that we analyze when considering whether to grant a stay pending appeal. See Nken, 556 U.S. at 425–26. But this court's rules provide some guidance. Ninth Circuit Rule 27-3, which governs emergency motions, provides that "[i]f a movant needs relief within 21 days to avoid irreparable harm, the movant must," among other things, "state the facts showing the existence and nature of the claimed emergency." If the movant fails to demonstrate that irreparable harm will occur immediately, emergency relief is not warranted, and there is no reason to address the merits of the movant's request.

Here, the Government has not shown that it is entitled to immediate relief. Its sole basis for seeking emergency action from this court is that "[t]he district court has . . . stymied the implementation of an Executive Branch policy . . . nationwide for almost three weeks." That alone is insufficient. It is routine for both executive and legislative policies to be challenged in court, particularly where a new policy is a significant shift from prior understanding and practice. E.g., West Virginia v. EPA, 597 U.S. 697 (2022); Dep't of Homeland Sec. v. Regents of the Univ. of Cal., 591 U.S. 1 (2020); Nat'l Fed'n of Indep. Bus. v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. 519 (2012). And just because a district court grants preliminary relief halting a policy advanced by one of the political branches does not in and of itself an emergency make. A controversy, yes. Even an important controversy, yes. An emergency, not necessarily.

To constitute an emergency under our Rules, the Government must show that its inability to implement the specific policy at issue creates a serious risk of irreparable harm within 21 days. The Government has not made that showing here. Nor do the circumstances themselves demonstrate an obvious emergency where it appears that the exception to birthright citizenship urged by the Government has never been recognized by the judiciary, see United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649, 693 (1898), and where executive-branch interpretations before the challenged executive order was issued were contrary, see, e.g., Walter Dellinger, Assistant Attorney General, Office of Legal Counsel, Legislation Denying Citizenship at Birth to Certain Children Born in the United States, 19 O.L.C. 340, 340–47 (1995).

To be clear, I am saying nothing about the merits of the executive order or how to properly interpret the Fourteenth Amendment. I merely conclude that, whatever the merits of the parties' respective positions on the issues presented, the Government has not shown it is entitled to immediate relief from a motions panel before assignment of the case to a merits panel. That said, the nature of this case and the issues it raises does warrant expedited scheduling for oral argument and assignment to a merits panel. And our general orders expressly permit this option: "In resolving an emergency motion to grant or stay an injunction pending appeal, the motions panel may set an accelerated briefing schedule for the merits of the appeal, order the case on to the next available argument calendar . . . , or order the case on to a specified argument calendar." 9th Cir. General Order 6.4(b).

Aside from the legal standard governing emergency relief, three prudential reasons support not addressing the merits of the Government's motion for a stay at this point. First, under our precedent, the decision of a motions panel, even if published, is not binding on the future merits panel. In East Bay Sanctuary Covenant v. Biden, we held that "[t]he published motions panel order may be binding as precedent for other panels deciding the same issue" at the motions stage, but it is not binding on the merits panel in the same case "because the issues are different" as presented in a motion to stay and in the underlying appeal of a preliminary injunction. 993 F.3d 640, 660 (9th Cir. 2021). A motions panel resolving a motion to stay "is predicting the likelihood of success of the appeal" whereas the "merits panel is deciding the likelihood of success of the actual litigation." Id. This is a fine, but important, distinction that has implications for the parties and the court. Because the procedural context informs the questions to be answered, "we do not apply the law of the case doctrine as strictly." Mi Familia Vota v. Fontes, 111 F.4th 976, 980 n.1 (9th Cir. 2024) (quoting United States v. Houser, 804 F.2d 565, 568 (9th Cir. 1986), abrogated on other grounds by Christianson v. Cold Indus. Operating Corp., 486 U.S. 800 (1988)). Therefore, anything a motions panel says about the merits of any of the issues presented in a motion for stay pending appeal is, on a very practical level, wasted effort.

Second, as a motions panel, we are not well-suited to give full and considered attention to merits issues. Take this case. The Government filed its emergency motion for a stay on February 12, requesting a decision by February 20—just over a week later. We ordered a responsive brief from the Plaintiff States by February 18, and an optional reply brief from the Government by February 19—one day before the Government asserts it needs relief. This is not the way reviewing courts normally work. We usually take more time and for good reason: our duty is to "act responsibly," not dole out "justice on the fly." East Bay Sanctuary Covenant, 993 F.3d at 661 (citation omitted). We must make decisions based on reasoned judgment, not gut reaction. And this requires understanding the facts, the arguments, and the law, and how they fit together. See TikTok Inc. v. Garland, 604 U.S. ---, 145 S. Ct. 57, 63 (2025) (observing that courts should be particularly cautious in cases heard on an expedited basis); id. at 75 (Gorsuch, J., concurring) ("Given just a handful of days after oral argument to issue an opinion, I cannot profess the kind of certainty I would like to have about the arguments and record before us."). Deciding important substantive issues on one week's notice turns our usual decision-making process on its head. We should not undertake this task unless the circumstances dictate that we must. They do not here. Third, and relatedly, quick decision-making risks eroding public confidence. Judges are charged to reach their decisions apart from ideology or political preference. When we decide issues of significant public importance and political controversy hours after we finish reading the final brief, we should not be surprised if the public questions whether we are politicians in disguise. In recent times, nearly all judges and lawyers have attended seminar after seminar discussing ways to increase public trust in the legal system. Moving beyond wringing our hands and wishing things were different, one concrete thing we can do is decline to decide (or pre-decide) cases on an emergency basis when there is no emergency warranting a deviation from our normal deliberate practice.

* * * * *

I do not mean to suggest that emergency relief is never warranted. There are cases where quick action is necessary. But they are rare. There must be a showing that emergency relief is truly necessary to prevent immediate irreparable harm. The Government did not make that showing here, and, therefore, there is no reason for us to say anything about whether the factors governing the grant of a stay pending appeal are satisfied. The Government may seek the relief it wants from the merits panel who will be assigned to preside over this case to final disposition. For these reasons, I concur in denying the Government's emergency motion for reasons different than relied on by the majority.

[Note: This order was issued yesterday, not today, and the post has been edited accordingly.]

The post Ninth Circuit Denies Government Request for Emergency Relief in Birthright Citizenship Case appeared first on Reason.com.

:@WilliamBaude: Prof. Ryan Snyder on the Eric Adams Case

There have been a lot of posts recently about the Department of Justice's treatment of the Eric Adams prosecution. I wanted to pass along this additional perspective I received from Professor Ryan Snyder of the University of Missouri, based on his recent article Trading Nonenforcement:

If There Was A Quid Pro Quo in the Eric Adams Case, It's Unconstitutional

Ryan Snyder

Last week, according to acting U.S. Attorney Danielle Sassoon, the Trump Justice Department made a deal with New York City Mayor Eric Adams: help enforce federal immigration law, and we'll drop the public-corruption case against you. People have rightly criticized that trade as politically motivated, as a weaponization of the justice system, and as a blow to the rule of law.

But those aren't the only problems with the deal: it's also unconstitutional. The President, and the executive-branch officers who assist him, have a duty to "take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed," U.S. Const. art. II, § 3, and to respect the separation of powers. Nonenforcement trades like this one—where the executive branch promises not to enforce the law against someone who has promised to help achieve unrelated goals—violate that duty.

(Obviously, there is a factual dispute about whether a quid pro quo occurred. I personally find Sassoon's account persuasive, but people can make up their own minds on that point. For purposes of this post, I will assume that Sassoon's account is correct.)

As I've explained in prior work, nonenforcement trades allow the executive branch to effectively impose binding rules on an individual or group without Congress's authorization. To achieve that result, the executive uses nonenforcement as a bargaining chip. First, the executive offers not to enforce the law against an individual in exchange for the individual's promise to do something that the executive wants but the law doesn't require. Second, the executive makes a threat: if the individual fails to uphold their end of the bargain, the executive will reverse course and enforce the law. If the individual accepts the offer—and they often do—the resulting trade effectively changes the law on the ground without amending the law on the books.

According to Sassoon, that's precisely what happened here. On January 31, Adams's counsel met with Deputy Attorney General Emil Bove and "repeatedly urged what amounted to a quid pro quo, indicating that Adams would be in a position to assist with the [Justice] Department's enforcement priorities only if the indictment were dismissed." Ten days later, Bove told Sassoon to drop the case against Adams because it had "unduly restricted [his] ability to devote full attention and resources to … illegal immigration." But Bove told Sassoon to dismiss the case "without prejudice," which would allow the Department to resurrect the case in the future. That's a nonenforcement trade: the Department promised not to enforce the public-corruption laws against Adams, Adams promised to help enforce federal immigration law, and if Adams fails to do so, he'll face prosecution.

Of course, nonenforcement trades don't formally have the force of law. In the real world, however, these trades can be every bit as binding as a statute or regulation. Take Adams as an example. If his case is dismissed without prejudice, Adams will face a choice: help enforce federal immigration law or be prosecuted. The law won't formally require Adams to help with immigration, but as a practical matter, he'll have no other choice.

Nonenforcement trades like the Adams deal violate the Constitution in two different ways. First, they violate the President's duty to faithfully execute the law. And second, they allow the executive branch to rewrite the law in violation of the separation of powers.

Let's start with faithful execution of the laws. The Constitution vests the "executive Power" in the President, U.S. Const. art. II, § 1, and provides that "he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed," U.S. Const. art. II, § 3. Those provisions create a general rule that the executive branch must enforce federal statutes. But scholars have identified four possible exceptions to that rule: (1) when the law is unconstitutional, (2) when the executive disagrees with the law on policy grounds, (3) when the executive lacks the evidence or resources to successfully enforce the law, and (4) when the executive believes that punishment is factually or morally unwarranted. To be sure, scholars disagree about the legitimacy of some of those exceptions. But these disagreements don't really matter here, because the Adams nonenforcement trade doesn't fit into any of the categories.

Most of the possible exceptions are easy to dismiss. The Justice Department didn't object to the public-corruption laws on constitutional or policy grounds. The Department didn't say that it lacks the evidence or resources to prosecute the case. And the Department didn't say that punishment is factually unwarranted—indeed, Bove's letter expressly says that the Department decided to drop the case "without assessing the strength of the evidence or the legal theories on which the case is based."

Moreover, the Department doesn't seem to believe that punishment is morally unwarranted. If the Department believed that, it would dismiss the case with prejudice and let Adams get on with his life. Instead, the Department wants to dismiss the indictment without prejudice, so it can dangle the threat of punishment over his head. That's not how you treat someone who doesn't deserve to be punished; it's how you strong-arm someone who is morally blameworthy.

Nonenforcement trades like this one also allow the executive branch to rewrite the law in violation of the separation of powers. The Constitution vests "[a]ll legislative Powers herein granted" in Congress, U.S. Const. art. I, § 1, which gives Congress the power to create binding rules for society and to decide how those rules should be enforced. Congress did that with the criminal laws that Adams has been accused of violating: for example, the wire-fraud statute creates a binding rule (don't commit wire fraud) and says how violations of that rule should be punished (fines or imprisonment up to 20 years). 18 U.S.C. § 1343. In laws like this one, the statutory text and purpose create a strong link between the rule and the punishment—namely, the punishment exists to punish people who broke the rule.

The Adams deal severs that link. Instead of using the wire-fraud punishment to punish wire fraud, as Congress prescribed, the executive branch is using it as a bargaining chip to buy something else. And the executive gets to decide what it buys without any guidance from Congress—effectively allowing the executive to exercise the legislative power of deciding how Congress's laws are enforced.

To be sure, this would be a closer case if the Justice Department were trading for something that was closely related to wire fraud—for example, declining to prosecute a minor participant in a wire-fraud scheme in exchange for testimony against the ringleader. But that's not what we have here; instead, the Department is trading for help with immigration enforcement, which has little to do with wire fraud. Absent Congress's authorization, the Department simply can't make trades like that without violating the separation of powers.

The Adams deal also illustrates one reason why nonenforcement trades are so dangerous: they can allow the executive branch to circumvent constitutional and statutory limits on their authority. In Printz v. United States, the Supreme Court held that the federal government can't force state and local officials to enforce federal law. As a result, the federal government can't force New York City's officials to help with immigration enforcement. The federal government can offer incentives, of course, but until recently, the city had refused to enforce federal immigration law to the Trump Administration's liking.

The Adams deal, however, allows the Administration to do indirectly what the Constitution prohibits it from doing directly. The Administration used its leverage over Adams—leverage created by the public-corruption case—to commandeer New York City's officials and force them to help carry out federal immigration law. That may or may not violate the strict terms of the anticommandeering doctrine, but it certainly violates its spirit. And if the Administration can use the Adams deal to circumvent the anticommandeering doctrine, why not other constitutional limits? For example, what would stop the Administration from changing the terms of the deal and also controlling Adams's speech?

Finally, I should note that plea bargains differ from the Adams trade in several ways (some of which have already been discussed on this blog). First, plea bargains don't usually pose the same problems under the Faithful Execution Clause. Most plea bargains result in a guilty plea, which means that the executive is enforcing the law to some extent. And even when the executive drops some charges as a result of a plea, that decision often reflects other judgments—such as uncertainty about the executive's ability to prove the charges, or a concern about the executive's resources—that fall into one of the recognized exceptions to the general duty to enforce the law. (Deferred-prosecution agreements and nonprosecution agreements, of course, are a different story.)

Second, plea bargains don't usually pose the same separation-of-powers problems as the Adams deal. Of course, plea bargains may require defendants to do something that the executive wants but the law doesn't require. But those requirements are often related to the law that the defendant violated (for example, testifying against a co-defendant). That's a far cry from the Adams deal, which trades nonenforcement of the wire-fraud statute for something that has nothing to do with wire fraud. For these reasons, accepting that the Adams deal crosses constitutional lines doesn't mean that all plea bargains do as well.

Two closing thoughts. First, I freely acknowledge that prior Presidents from both parties have made nonenforcement trades that violate the Constitution. But that doesn't make this trade constitutional—and if each new President could violate the Constitution simply because earlier ones did, we wouldn't have a Constitution at all. Second, it's all too common nowadays for people to argue that something is unconstitutional simply because they dislike it. I certainly don't wish to contribute to that trend. But some things are distasteful and unconstitutional, and when that's the case, I have no problem saying so. This is one of those times.

The post Prof. Ryan Snyder on the Eric Adams Case appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Greg Lukianoff (FIRE) on "Being Non-Partisan in a Partisan Age"

An excellent post, about an organization that I very much admire. An excerpt:

Be willing to make common cause with ideological opponents

As he contemplated the challenges and pitfalls of advocating for abolition, Frederick Douglass began to see that dialogue with those who saw things differently was critical to achieving his goals. When the more stringent and radical abolitionists, whose motto was "No union with slaveholders," criticized Douglass' approach, he famously replied, "I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong."

We can learn a great deal from Douglass' wisdom here. The only way to make real progress is by forming coalitions around specific issues and collaborating, even if we remain deeply divided on other topics. You can't claim to be non-partisan if you only call out one side when they do bad or only praise one side when they do good. You also can't claim to be non-partisan if you won't accept help from or collaborate with your ideological opponents on issues where you actually agree.

And here's the thing: If you are waiting to only ally with a person, a politician, or—worse still—a political party that is never wrong on matters of freedom of speech, you will never partner with anybody. If we're being honest, by that standard you likely wouldn't even be able to partner with yourself….

(Note that I have done a bit of paid consulting for FIRE in the past, and FIRE is representing me pro bono in a couple of cases; I have also supported FIRE's work in the past pro bono on many occasions. I'm passing this along, though, solely because I liked it.)

The post Greg Lukianoff (FIRE) on "Being Non-Partisan in a Partisan Age" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Court Orders Newspaper to Remove Editorial Critical of City of Clarksdale (Miss.) Officials

I was traveling yesterday (and I'm continuing the trip today), so I didn't have the time to put something of my own together on this, but I highly recommend this thread from Adam Steinbaugh (FIRE). The opening paragraph:

Wow: The City of Clarksdale, Mississippi, got a court order yesterday directing a newspaper to delete an editorial criticizing city officials -- without a hearing. Here's the TRO issuing the prior restraint: …

I will add one possibly clarifying detail: Many courts have in recent decades allowed anti-libel injunctions requiring the removal of material after it has been found to be libelous after trial (or after a default judgment), and barring the reposting of the specific statements found to be libelous. But the First Amendment continues to forbid pre-trial injunctions, and especially "ex parte" ones such as this one, which were issued without even a preliminary adversary hearing. And that's true even if the order is issued after the article is published; under modern First Amendment law, a "prior restraint" is one issued prior to a trial on the merits, rather than prior to publication:

The special vice of a prior restraint is that communication will be suppressed … before an adequate determination that it is unprotected by the First Amendment.

That, though, is just one of the many apparent defects of this injunction; read Steinbaugh's thread for much more.

The post Court Orders Newspaper to Remove Editorial Critical of City of Clarksdale (Miss.) Officials appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers