Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 157

February 26, 2025

[Sasha Volokh] Cert Petition in Georgia Adult-Entertainment Tax Case

[The Supreme Court should reverse the Georgia Supreme Court's judgment in Georgia Ass'n of Club Executives v. Georgia.]

A couple of weeks ago, I filed a cert petition in Georgia Ass'n of Club Executives v. Georgia and Georgia Ass'n of Club Executives v. O'Connell. (For procedural reasons, these were filed as two separate cases, but they raise identical issues, and the Georgia Supreme Court decided them in a combined opinion.)

Together with the team at Freed Grant LLC, we challenged a Georgia statute imposing a tax on adult entertainment establishments, a group of businesses defined in a content-discriminatory way, based on whether "[t]he entertainment or activity therein consists of nude or substantially nude persons dancing with or without music or engaged in movements of a sexual nature or movements simulating sexual intercourse, oral copulation, sodomy, or masturbation . . . ." Our position was that, as a content-discriminatory enactment, this tax should be evaluated under strict scrutiny—and should fail because the government could have raised the same amount of taxes in a non-content-discriminatory way, out of general revenues.

This case should be of interest even if you're not interested in adult entertainment (indeed, even if you're hostile to adult entertainment). The big question here is whether a facially content-discriminatory enactment (that would otherwise be evaluated under strict scrutiny) should be considered content-neutral (and thus evaluated under intermediate scrutiny) if it has a content-neutral justification. This means this case is closely related to the abortion-clinic buffer-zone cases that rely on Hill v. Colorado—and, as you may have read on this blog (here or here), the Supreme Court has recently denied cert in a case that presented the issue of whether to overruled Hill.

Hopefully the Supreme Court will consider our cert petition sometime in March or April. I'm reprinting the main text of the introductory part of our cert petition below (some portions and citations omitted). If you want to write an amicus brief, you have until March 20 to file one—let me know by personal message if you're interested! If you want to read the whole thing in its beautiful formatted form (thanks to Counsel Press), you can click here.

* * *

Question Presented

A Georgia statute imposes a tax that, on its face, singles out businesses defined by the content of their expression; the State seeks to justify the tax by the need to address "secondary effects." Is this tax subject to strict scrutiny under the First Amendment because it is facially content-discriminatory, as recently reaffirmed by Reed v. Town of Gilbert, 576 U.S. 155 (2015), or does a content-neutral rationale make the tax subject to intermediate scrutiny under City of Renton v. Playtime Theatres, Inc., 475 U.S. 41 (1986)?

Statutory Provisions Involved

Ga. Code Ann. § 15-21-201(1) provides, in relevant part:

(1) "Adult entertainment establishment" means any place of business or commercial establishment where alcoholic beverages of any kind are sold, possessed, or consumed wherein:

(A) The entertainment or activity therein consists of nude or substantially nude persons dancing with or without music or engaged in movements of a sexual nature or movements simulating sexual intercourse, oral copulation, sodomy, or masturbation . . . .

Ga. Code Ann. § 15-21-209 provides, in relevant part:

(a) By April 30 of each calendar year, each adult entertainment establishment shall pay to the commissioner of revenue a state operation assessment equal to the greater of 1 percent of the previous calendar year's gross revenue or $5,000.00. This state assessment shall be in addition to any other fees and assessments required by the county or municipality authorizing the operation of an adult entertainment business. . . .

(c) The assessments collected pursuant to this Code section shall be remitted to the Safe Harbor for Sexually Exploited Children Fund Commission, to be deposited into the Safe Harbor for Sexually Exploited Children Fund.

Statement

This Court has long held that content-discriminatory (i.e., content-based) governmental enactments must satisfy strict scrutiny; a content-neutral justification cannot transform a facially content-discriminatory enactment into a content-neutral one. This principle goes back several decades. See, e.g., Arkansas Writers' Project v. Ragland, 481 U.S. 221 (1987); Simon & Schuster v. Members of the N.Y. State Crime Victims Bd., 502 U.S. 105 (1991); Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project, 561 U.S. 1 (2010). And this Court has recently strongly reaffirmed this principle. See Reed v. Town of Gilbert, 576 U.S. 155, 163 (2015); Barr v. Am. Ass'n of Polit. Consultants, 591 U.S. 610, 618 (2020) (plurality opinion) [hereinafter AAPC].

However, in other cases, this Court has stated that even a facially content-discriminatory regulation can be treated as a content-neutral "time, place, and manner restriction" and evaluated under intermediate scrutiny, so long as it is justified without reference to content. This rule has been stated in the context of adult entertainment, where the government's claimed justification has been the need to combat "secondary effects." City of Renton v. Playtime Theatres, Inc., 475 U.S. 41 (1986). But this "content-neutral justification" rule has since grown to be applied in very different areas—for instance, the regulation of sound amplification in a municipal park, see Ward v. Rock Against Racism, 491 U.S. 781, 799 (1989), and abortion-clinic buffer zones, see Hill v. Colorado, 530 U.S. 703, 719 (2000).

And this Court has assumed the validity of the content-neutral justification rule in even more areas—the regulation of political protests near foreign embassies, see Boos v. Barry, 485 U.S. 312, 320 (1988), the regulation of the display of symbols that arouse anger based on factors such as race, see R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul, 505 U.S. 377, 389 (1992), and the regulation of newsracks, see City of Cincinnati v. Discovery Network, Inc., 507 U.S. 410, 430 (1993). In some of these cases, the precise doctrinal statement has not made a difference (the regulation in Ward, for instance, would have been content neutral under any standard), but in other cases (such as City of Renton and Hill), the reliance on the content-neutral justification theory made a real difference to the bottom line.

These two lines of doctrine are inconsistent. Or, at least, they are in substantial tension with each other. Perhaps each doctrine is valid within its own domain—but it is unclear what these domains are. Clearly, the content-neutral justification rule is not limited to the handful of assorted areas where those cases arose, including adult entertainment and abortion-clinic buffer zones. Nor is that framework always used for all cases within those areas. In United States v. Playboy Entertainment Group, 529 U.S. 803 (2000), this Court applied strict scrutiny in an adult-entertainment context. And in McCullen v. Coakley, 573 U.S. 464 (2014), this Court applied intermediate scrutiny in an abortion-clinic buffer-zone context without relying on the City of Renton/Hill reasoning, endorsing the facial approach that it would later strongly restate in Reed. Id. at 479-81.

The City of Renton framework was developed in a zoning and land-use context, and its rationale has been closely tied to the justifications for zoning and land-use regulation; indeed, this Court has described City of Renton and its progeny as "[o]ur zoning cases." Playboy, 529 U.S. at 815. And yet, lower courts—including the Georgia Supreme Court in this case, and the Texas Supreme Court in a similar case, Combs v. Tex. Entm't Ass'n, 347 S.W.3d 277, 286 (Tex. 2011)—have extended the content-neutral justification rule, even after Reed. These courts have applied City of Renton to facially content-discriminatory taxes, even though there is no precedent from this Court for extending the City of Renton/Hill doctrine that far. There has also been confusion among lower courts about the fate of City of Renton after Reed. Some have assumed that City of Renton is still good law; others have held that some of their pre-Reed case law that relied on City of Renton has been abrogated.

This Court should grant certiorari in this case to resolve this confusion among lower courts and to prevent courts from diluting the Reed doctrine by an unjustified expansion of City of Renton/Hill analysis. This case presents the content-neutral justification reasoning cleanly, without any of the vehicle problems that may have led this Court to deny certiorari in recent cases that presented the issue in the context of abortion-clinic buffer zones, like Bruni v. City of Pittsburgh, 141 S. Ct. 578 (2021) (mem.) (denying certiorari), Vitagliano v. County of Westchester, 144 S. Ct. 486 (2023) (mem.) (denying certiorari), and Reilly v. Harrisburg, 144 S. Ct. 1002 (mem.) (2024) (denying certiorari). See Bruni, 141 S. Ct. at 578 (Thomas, J., respecting denial of certiorari) ("[T]he Court should take up this issue in an appropriate case to resolve the glaring tension in our precedents" between the Reed/McCullen and Hill frameworks).

There are at least three ways that this Court could clarify the doctrine.

First, this Court could overrule City of Renton/Hill intermediate scrutiny as being inconsistent with the Reed rule of strict scrutiny. After all, this Court has already stated that Hill is a "distort[ion]" of "First Amendment doctrines," Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Org., 597 U.S. 215, 287 & n.65 (2022), and the Hill problem extends to City of Renton and other cases as well. As some of this Court's Justices have noted, this Court's intervening decisions have "all but interred" Hill, rendering it "an aberration in [the Court's] case law." City of Austin, 596 U.S. at 91-92, 103-04 (2022) (Thomas, J., joined by Gorsuch & Barrett, JJ., dissenting); Bruni, 141 S. Ct. at 578 (Thomas, J., respecting denial of certiorari) (noting that the Court's use of intermediate scrutiny in Hill "is incompatible with current First Amendment doctrine" (quoting Price v. City of Chicago, 915 F.3d 1107, 1117 (7th Cir. 2019))).

Moreover, Hill has been criticized ever since it was decided, even by commentators who support abortion rights. See, e.g., Erwin Chemerinsky, Content Neutrality as a Central Problem of Freedom of Speech: Problems in the Supreme Court's Application, 74 S. Cal. L. Rev. 49, 59 (2000); Kathleen M. Sullivan, Sex, Money, and Groups: Free Speech and Association Decisions in the October 1999 Term, 28 Pepp. L. Rev. 723, 737-38 (2001). Much of the critique of the Hill reasoning is a critique of the entire content-neutral justification rule; this case would thus allow this Court to clarify that strict scrutiny is the rule in all these diverse areas.

Second, this Court could clarify that the City of Renton reasoning is strictly limited to the zoning and land-use context in which it arose. The City of Renton reasoning would thus no longer be available to support regulations that have nothing to do with land use (such as abortion-clinic buffer zones), and certainly would not be available to support non-regulatory enactments, such as the tax at issue in this case.

Third, this Court could clarify that, however far the City of Renton reasoning extends, it certainly does not apply to taxation. This option would retain the City of Renton reasoning for regulatory cases of various kinds (perhaps including buffer zones), but would prevent the expansion of the secondary effects doctrine to taxation—an expansion that would be inconsistent with cases like Arkansas Writers' Project and that could substantially undo the Reed rule of strict scrutiny.

Either way, this Court has been right to stress the general rule that content discrimination is highly suspect and that strict scrutiny is the norm in such cases, even when the government asserts content-neutral justifications. "The vice of content-based legislation—what renders it deserving of the high standard of strict scrutiny—is not that it is always used for invidious, thought-control purposes, but that it lends itself to use for those purposes." Madsen v. Women's Health Center, Inc., 512 U.S. 753, 794 (1994) (Scalia, J., concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting in part). The City of Renton/Hill exception should not continue to expand to erode or swallow up this salutary rule.

1. The State Operation Assessment

In 2015, the Georgia Legislature passed a tax—labeled a "state operation assessment"—on "adult entertainment establishment[s]." Ga. Code Ann. §§ 15-21-209, -201(1)(A). The purpose of the tax was to fund the Safe Harbor for Sexually Exploited Children Fund ("Safe Harbor Fund"), the primary purpose of which "is to disburse money to provide care and rehabilitative and social services for sexually exploited children." Id. § 15-21-202(c).

The category of "[a]dult entertainment establishment" was defined, in part, in a way that facially discriminates based on content: an establishment could qualify by having "entertainment" that "consists of nude or substantially nude persons . . . engaged in movements of a sexual nature" or simulating specified sexual activities. Id. § 15-21-201(1)(A).

2. The Georgia Trial Court Opinion

Petitioner Georgia Association of Club Executives, an organization of adult entertainment clubs in Georgia, sued to enjoin the collection of the tax. After some initial litigation, petitioner filed new complaints in the Georgia trial court against the State of Georgia and the Commissioner of the Georgia Department of Revenue (now Frank O'Connell), arguing that the tax violated the First Amendment. The cases against the State of Georgia and against Revenue Commissioner O'Connell were separate but raised substantively identical issues.

First, petitioner argued that the tax was content discriminatory and therefore had to be evaluated under strict scrutiny. Petitioner conceded that the State's interest, fighting child sexual exploitation, was compelling. But the tax could not satisfy strict scrutiny because there existed a less discriminatory alternative: funding the Safe Harbor Fund out of general revenues. The tax did not fall within the City of Renton exception. The City of Renton secondary effects doctrine has always been a limited exception to the general rule that content-discriminatory enactments are subject to strict scrutiny; and City of Renton, which was developed in a land use and zoning context, does not apply to taxes.

Next, petitioner argued that even if the tax were evaluated under intermediate scrutiny, it would still fail, because it would still have to be "narrowly tailored to serve a significant governmental interest." See, e.g., Clark v. Community for Creative Non-Violence, 468 U.S. 288, 293-94 (1984). In the intermediate scrutiny context, narrow tailoring merely requires that an enactment "promote[] a substantial government interest that would be achieved less effectively absent the regulation." Ward, 491 U.S. at 799 (internal quotation marks omitted). But the only interest ever asserted by the State was to raise revenue to fund the programs that fell within the purpose of the Safe Harbor Fund. And, because that interest would be served just as effectively if the money were raised from general revenues, the tax failed narrow tailoring even in the context of intermediate scrutiny. Moreover, petitioner argued, the tax failed intermediate scrutiny for the additional reason that the evidence relied on by the Legislature was woefully insufficient to establish a rational connection between adult entertainment establishments and child sexual exploitation.

Finally, petitioner raised an overbreadth challenge.

In the case against Revenue Commissioner O'Connell, the Georgia trial court (adopting verbatim respondents' proposed order) upheld the tax, ruling that strict scrutiny did not apply, that the tax satisfied intermediate scrutiny, and that the tax was not overbroad. In the (substantively identical) case against the State of Georgia, the Georgia trial court incorporated all of its legal reasoning from the case against the Commissioner.

3. The Georgia Supreme Court Opinion

Petitioner appealed both cases to the Georgia Supreme Court. In a combined opinion, the Georgia Supreme Court affirmed the trial court by a vote of 7-1.

First, the court held, relying on City of Renton, that the tax was content neutral because it was aimed at the suppression of secondary effects, and that it was therefore not subject to strict scrutiny.

Second, the court assumed that the tax was subject to intermediate scrutiny and held that it met that standard. Though the State had only asserted a bare revenue-raising interest, the court recharacterized the State's interest, asserting that "implicit within the State's interest is an element of seeking not to burden taxpayers in general with the costs of remedying the harm that the adult entertainment industry causes." That interest was "important" within the meaning of intermediate scrutiny. And, the court said, deferring to the State's empirical studies, the tax furthered that interest. The State's interest was unrelated to suppressing free expression. And the tax's burden on expression was incidental and promoted the State's interest (as recharacterized) more effectively than if the money came from general revenues.

Third, the court held that the tax was not overbroad.

Justice Warren dissented. She agreed with the majority that the tax should be considered content neutral in light of City of Renton, and she wrote that the tax should thus be analyzed under intermediate scrutiny. But she disagreed with the majority on how to characterize the State's interest. She argued that the State's interest was merely raising revenue; the State's supposed interest in targeting the tax at the industry responsible for the secondary effects was not one that it had ever argued. In her view, this recharacterization "undermine[d] . . . the four-prong test [of United States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968)] and create[d] potential work-arounds for government entities to target protected expression." When the State's interest was properly viewed as the interest in raising revenue, it failed narrow tailoring because of the availability of generally applicable taxes.

The Georgia Supreme Court denied reconsideration in the two cases.

* * *

Well, that's the introductory material from the cert petition—read the whole thing.

The post Cert Petition in Georgia Adult-Entertainment Tax Case appeared first on Reason.com.

February 25, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Federal Judge Sanctions Attorneys For Judge-Shopping

[No, this did not occur in Texas. ]

Last March, I wrote about progressive attorneys in Alabama who tried to steer a transgender case to a Carter appointee. At the time, the court found there were surreptitious steps taken. Now, Judge Liles C. Burke issued a 230-page opinion that sanctioned three attorneys The Court refers one of the attorneys for potential prosecution to the U.S. Attorney for the Middle District of Alabama.

Here is the introduction:

This case requires the Court to consider a malignant practice that threatens the orderly administration of justice: judge-shopping. The lead attorneys in this case— a high-profile challenge to Alabama state law—tried to avoid their assigned judge by voluntarily dismissing one case and filing anew with different plaintiffs in a neighboring federal district court. This was not just a strategic litigation decision; it was a calculated effort to subvert the rule of law.

The case began in April 2022, when two teams of attorneys from some of the nation's leading law firms and advocacy groups sued the State of Alabama to block enforcement of a new felony healthcare ban on medical treatments for transgender minors. The attorneys had labored over these cases for nearly two years in advance so they could sue the State as soon as the proposed ban became law; and when the Governor signed the legislation on April 8, 2022, they sued immediately. The first case, Ladinsky v. Ivey, was filed that afternoon, No. 5:22-cv-447-LCB (N.D. Ala. Apr. 8, 2022) ("Ladinsky"). The second, Walker v. Marshall, was filed the following Monday, No. 5:22-cv-480-LCB (N.D. Ala. Apr. 11, 2022) ("Walker"). Both teams felt immense pressure to secure an injunction before the law's May 8 effective date. But within a week, both teams abandoned their cases. Walker and Ladinsky were reassigned to this Court on the afternoon of April 15, and less than two hours later each team had voluntarily dismissed its case under Rule 41(a)(1)(A)(i). By their own admission, these attorneys were "try[ing] to game the system": one team abandoned the litigation altogether, while the other dropped everything, regrouped, mustered new plaintiffs, and filed suit in another federal district court for the express purpose of manipulating the courts' random case-assignment procedures to avoid the risk of an unfavorable judgment from this Court. In re Vague, 2:22-mc-3977, Doc. 75 at 141. . . .

But the plaintiffs' filings in Walker and Ladinsky sparked concern among the federal bench that counsel had tried either to manipulate or circumvent the random case-assignment procedures for the Northern and Middle Districts of Alabama. In May 2022, a three-judge panel consisting of the chief judges for the Northern, Middle, and Southern Districts of Alabama (or their designees) was convened to investigate their conduct. After six months developing a substantial evidentiary record and eleven months deliberating, the Panel found that eleven lead attorneys from Walker and Ladinsky (the "Respondents") had committed misconduct by judge-shopping. Doc. 339. On October 3, 2023, the Panel published its findings in a 53-page Final Report of Inquiry, which it referred to this Court for further proceedings. . . .

Now, for the reasons discussed below, the Court PUBLICLY REPRIMANDS attorneys Melody Eagan and Jeffrey Doss for their intentional, bad-faith attempts to manipulate the random case assignment procedures for the Northern and Middle Districts of Alabama, DISQUALIFIES them from further participation in this case, and REFERS the matter of their professional misconduct to the Alabama State Bar. The Court declines to exercise its discretion to suspend Eagan and Doss from practice in the Middle District of Alabama. Moreover, the Court PUBLICLY REPRIMANDS Carl Charles for his repeated, intentional, bad-faith misrepresentations of key facts to the three-judge panel about his call to Judge Thompson's chambers, imposes MONETARY SANCTIONS in the amount of $5,000, and REFERS this matter to the United States Attorney for the Middle District of Alabama and Charles's licensing bar organizations.

This is actual judge shopping, and it is problematic. Filing cases, consistent with local rules and venue choices created by Congress, is entirely lawful.

The post Federal Judge Sanctions Attorneys For Judge-Shopping appeared first on Reason.com.

[David Post] The American People vs the Trump Administration

[A very useful resource for those interested in the many lawsuits challenging one or another Trump Administration outrage]

The Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse has an extremely useful compilation showing the current progress in all cases challenging Trump Administration policies filed to date. The website is here. [There is also a separate site for cases involving, but not challenging, Trump policies.] [I'm told that students at the University of Michigan Law School are responsible for keeping these sites up to date - kudos to them]

By my count, there are 28 separate cases** in which a TRO or a Preliminary Injunction has been issued against the government's implementation of its policies.

**Six cases involve challenges to Trump's patently (and rather embarrassingly) unconstitutional Executive Order regarding birthright citizenship, six involve challenges to employment actions, two involve DOGE access to government information, four involve Trump Administration policies regarding transgender rights, one involves immigration policy, eight challenge various aspects of the Spending Freeze(s), and one involves Trump Administration policies dismantling DEI initiatives.

Wow! Of course, we all know that TROs and PIs are not adjudications on the merits of any case; they do not involve a determination the Administration's actions have been unlawful.

But still . . . TROs and PIs do require judges to find that there is a "substantial likelihood" that the challenge will succeed, on the merits - i.e., that the challenger will be able to show that the government has behaved unlawfully. Twenty-eight judges have done so - 28! Surely, it's a record - 28 restraining orders in five weeks!

I know, I know - "That's why we elected him!! Break everything down! Smash everything!! Get rid of all that stupid 'rule of law' nonsense!! No man who saves his country is violating the law!!"

Maybe so. But I kind of liked that rule of law nonsense, where Presidents were supposed to follow the law, like everyone else. It served us pretty well, over the last 250 years. Such a shame to see it go. I think we'll miss it when it's gone.

The post The American People vs the Trump Administration appeared first on Reason.com.

[Michael Abramowicz] Major Technological Questions

The George Washington University Law Review has now published "Major Technological Questions," a contribution by John Duffy and myself to a symposium on Legally Disruptive Emerging Technologies. (You can find all of the symposium contributions here.) In this post, John and I will provide a brief overview of our argument. We'll elaborate more in several subsequent posts.

Our core argument is that courts and agencies should hesitate to interpret ambiguous pre-existing legal authority as resolving legal questions newly raised by major technological developments. As the title suggests, we draw an analogy to the "major questions doctrine." That doctrine can be understood as holding that an administrative agency seeking to resolve major questions of vast or political significance must have a fairly explicit authorization in pre-existing statutes that supports the agency's power to address such "major questions." If such an explicit authorization is absent, the pre-existing statutes are interpreted so that the "major questions" are viewed as outside the ambit of the agency's statutory authorization.

Our approach to major technological questions is analogous but not identical. We argue that, when significant new technologies and with them major new legal questions arise, all legal actors (both agencies and courts) should typically view those questions as falling outside the ambit of pre-existing legal materials, including not only statutes but also judicially created common-law doctrines. The consequences of such a view varies. For agencies, the consequence is likely a lack of statutory authorization and thus less power (just as with the major questions doctrine). For courts, the consequence of viewing pre-existing precedents as not addressing new technological issues may well be to give the courts more power because the courts would then not be constrained by precedent.

We'll give some examples of past and current controversies in later posts, but the idea can be seen clearly in a hypothetical. Imagine that in the future, a technological development (maybe even the invention of Mr. Fusion Home Energy Reactors) makes it possible for individual households to generate substantial amounts of power and sell that power directly to their neighbors. The question might then arise whether each individual household is a "public utility" under the relevant statute governing administrative action or is sufficiently "public" under judicial precedents governing the reach of traditional regulatory powers. Those questions, it should be noted, may not fall within the "major questions doctrine" because, at least at first, only a few early adopters may be buying the home fusion devices.

The lawyerly instinct would be to look, say, to the pre-existing administrative statutes and judicial precedents to answer those questions. We think, however, that the pre-existing definition of "public utility" under statutory law or the pre-existing concept of a "public" business under judicial cases simple may not shed light on the fundamental policy questions in this radically different world. Given that pre-existing lawmakers probably did not consider whether individual households should have to meet, say, paperwork and procedural requirements imposed on large electric utilities, the pre-existing legal sources might reasonably be interpreted as simply being inapplicable. That doesn't mean that we necessarily favor that such home electric sales should ultimately be unregulated, but the relevant lawmaking body (the Congress for federal statute law and the courts for judge-made law) may very well have to act to address the relevant new legal questions posed by the advent of the technology.

We do not claim major technological questions as a subcategory of the major questions doctrine. As noted with the fusion hypothetical, many major technological questions may be presented at the first dawn of a new technology when the social or economic stakes hardly seem "major." Rather, our approach to major technological questions follows a fundamental insight of the major questions doctrine: sometimes lawyers and judges are looking for answers in texts that simply cannot provide them.

Ultimately, our argument is a prudential one, and we do not claim to prove wrong someone who has more faith in the power of legal actors to extract from old, ambiguous sources clear meaning relevant to entirely new problems. We also recognize that our approach may have more purchase in some contexts than others. Reasonable people may disagree about whether a technological development and the legal questions surrounding it are sufficiently "major" to justify our approach. Nevertheless, our approach is, we believe, especially justified in three circumstances: first, when a contrary approach would give decisional power concerning the new technology to an agency or other regulatory body that lacks the expertise necessary to make the relevant policy decisions; second, when the principal costs and benefits of the new technology are not closely related to those that animated the lawmaking entity that created the pre-existing legal authority; and third, when a contrary approach would greatly limit the emergence of, and experimentation with, the new technology.

A potential critique of our approach is that it often favors a deregulatory default. While that may be true, the fundamental goal of our approach is to make sure that the relevant lawmaking bodies have grappled with the relevant policy issues and come to some considered resolution. Where the relevant lawmaking body is a legislature as opposed to a common-law court, our approach can be viewed as favoring democratic action. To the extent that our approach still has a deregulatory tilt, that tilt is a positive. In common lawmaking, courts can legitimately consider all sorts of policy considerations, including the strong historical support in our legal culture to innovation and progress as exemplified by our constitutionally authorized patent system. In statutory law, our approach is no less appropriate than the major questions doctrine, at least where there is ambiguity. Of course, sometimes the law will discourage innovation with antiquated justifications but yet be sufficiently clear. An example may be the Federal Aviation Administration's nearly complete ban on supersonic aircraft. Where the law is genuinely ambiguous, however, our approach would help to make sure that regulatory decisions are made with full consideration of the relevant policy grounds (by the legislature or by the courts) and are not developed merely by having lawyers and judges squinting to find answers in dusty legal materials that don't offer them.

In the next blog posts, we'll apply our approach first to some old technologies (the inventions of photography and airplanes) and then to some new ones (cryptocurrencies and artificial intelligence).

The post Major Technological Questions appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "Mississippi Town Votes to Drop Lawsuit That Had Forced Newspaper to Take Down Editorial"

From the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) (see here for my original post on the case):

After receiving widespread condemnation for obtaining a temporary restraining order that forced Mississippi's Clarksdale Press Register to take down an editorial critical of the city, Clarksdale's Board of Mayor and Commissioners voted Monday to drop the lawsuit.

Last week, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression first called national attention to the plight of the Press Register after the city sued the small-town Coahoma County newspaper to force it to take down an editorial criticizing local officials. On Friday, FIRE agreed to defend the Press Register, its editor, and parent company in court to have the unconstitutional restraining order lifted…

By Monday, Clarksdale's Board had convened, voted not to continue with the lawsuit, and filed a notice of voluntary dismissal with the court. That means the city's suit is over and with it the restraining order preventing the Press Register from publishing its editorial….

The controversy began when the city of Clarksdale held an impromptu meeting on Feb. 4 to discuss sending a resolution asking the state legislature to let it levy a 2% tax on products like tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana. By state law, cities must notify the media when they hold such irregular "special-called meetings," but the Press Register did not receive any notice.

In response, the Press Register blasted the city in an editorial titled "Secrecy, Deception Erode Public Trust," and questioned their motive for freezing out the press. "Have commissioners or the mayor gotten kick-back from the community?" the editorial asked. "Until Tuesday we had not heard of any. Maybe they just want a few nights in Jackson to lobby for this idea – at public expense." …

Rather than taking their licks, the Clarksdale Board of Commissioners made a shocking move by voting to sue the Press Register, its editor and publisher Floyd Ingram, and its parent company Emmerich Newspapers for "libel." Last Tuesday, Judge Martin granted ex parte – that is, without hearing from the Press Register – the city's motion for a temporary restraining order to force it to take down the editorial.

By silencing the Press Register before they could even challenge Clarksdale's claims, Judge Martin's ruling represented a clear example of a "prior restraint," a serious First Amendment violation. Before the government can force the removal of any speech, the First Amendment rightly demands a determination whether it fits into one of the limited categories of unprotected speech or otherwise withstands judicial scrutiny. Otherwise, the government has carte blanche to silence speech in the days, months, or even years it takes to get a final ruling that the speech was actually protected.

Judge Martin's decision was even more surprising given that Clarksdale's lawsuit had several obvious and fatal flaws. Most glaringly, the government itself cannot sue citizens for libel. As the Supreme Court reaffirmed in the landmark 1964 case New York Times v. Sullivan, "no court of last resort in this country has ever held, or even suggested, that prosecutions for libel on government have any place in the American system of jurisprudence."

But even if the Clarksdale commissioners had sued in their personal capacities, Sullivan also established that public officials have to prove not just that a newspaper made an error, but that it did so with "actual malice," defined as "knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false." Clarksdale's lawsuit didn't even attempt to prove the Press Register editorial met that standard.

Finally, libel requires a false statement of fact. But the Press Register's broadside against city officials was an opinion piece that expressed the opinion that there could be unsavory reasons for the city's lack of candor. The only unique statement of fact expressed in the editorial — that Clarksdale failed to meet the legal obligation to inform the media of its meeting — was confirmed by the city itself in its legal filings….

Like many clumsy censorship attempts, Clarksdale's lawsuit against the Press Register backfired spectacularly by outraging the public and making the editorial go viral. After FIRE's advocacy, the small Mississippi town's lawsuit received coverage from the New York Times, The Washington Post, Fox News, and CNN, and condemnation from national organizations like Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press and the Committee to Protect Journalists. Other Mississippi newspapers have stepped up and published the editorial in their own pages to ensure its preservation….

The post "Mississippi Town Votes to Drop Lawsuit That Had Forced Newspaper to Take Down Editorial" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Paul Cassell] Did Glossip and the Oklahoma Attorney General Collusively Conceal Evidence to Win Their U.S. Supreme Court Case?

[Justice Thomas observes in his dissent that "the parties collusively excluded" evidence—which I presented to the Court for the victim's family—"in order to reach a predetermined outcome." And the Court majority offers no defense of this deceitful maneuver.]

Today the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of death row inmate Richard Glossip. By a 5-3 majority, the Court found that the prosecutors in the case "knowingly" failed to correct false testimony from an important state witness at Glossip's murder trial. But in reaching this conclusion, the majority refused to consider highly relevant evidence that I presented for the victim's family disproving this finding. The majority concluded that my evidence constituted "extra-record materials not properly before the Court." But as Justice Thomas pointed out in his powerful dissenting opinion, the parties in the case (Glossip and the Oklahoma Attorney General's Office) "collusively excluded this highly relevant evidence" from the record. The parties' dubious maneuver raises serious questions about the justice of today's ruling—and about our nation's treatment of crime victims' families.

VC readers will recall that I blogged about this case earlier, explaining the story behind how death row inmate Glossip concocted a phantom "Brady violation" and got Supreme Court review. See Part I, Part II, and Part III.) To quickly summarize, Glossip was convicted of the 1997 murder of Barry Van Treese in 1998. After a reversal for ineffective assistance of counsel, Glossip was convicted again in 2004. The main state witness was Justin Sneed, who confessed that he (Sneed) had murdered Van Treese after Glossip had commissioned the murder.

In 2007, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals ("OCCA") affirmed Glossip's conviction and sentence, rejecting Glossip's claim that the evidence proved only that he was an accessory-after-the-fact. In the years since, courts have rejected multiple challenges by Glossip to his conviction and death sentence.

Nearly two decades later, Oklahoma was preparing to execute Glossip when a new Attorney General, Gentner Drummond, was elected. Shortly after assuming office in January 2023, and apparently sensing political opportunity, the new Attorney General hastily commissioned an "independent" review of Glossip's conviction. Conveniently, General Drummond hired Rex Duncan, his lifelong friend and a political supporter who possessed limited experience in capital litigation. Duncan suddenly discovered "new" evidence the prosecution had purportedly concealed from the defense.

As the tale was told in Glossip's and Oklahoma's briefs before the Oklahoma courts and, ultimately, the Supreme Court, the trial prosecutors concealed from Glossip's defense team information about Sneed's lithium usage and related psychiatric care. This story rested on an interpretation of notes the prosecutors took during a pretrial interview of Sneed. Specifically, General Drummond asserted that the handwritten notes indicated that Sneed told the prosecutors "that he was 'on lithium' not by mistake, but in connection with a 'Dr. Trumpet.'"

The OCCA rejected the argument and, after relisting the case twelve times, the Supreme Court granted cert. I filed a motion to participate in oral argument for the family. But, instead, the Court appointed an amicus to argue for affirming the judgment below.

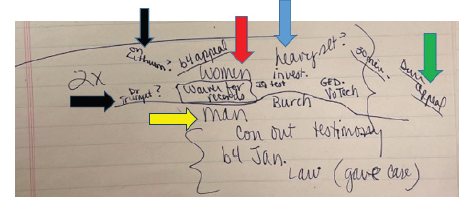

I filed an amicus brief in the case, explaining that the prosecutors' handwritten notes did not somehow reveal that prosecutors knew about Sneed's alleged lithium prescription and usage, but rather merely showed the prosecutors were recording Sneed recounting what Glossip's defense attorney's were asking about. Specifically, I explained that the notes from one of the prosecutors contained question marks—as shown by the references marked with the black arrows below:

Stepping back to examine the surrounding context of these two notes clarifies that the prosecutor was simply recording Sneed recounting what Glossip's defense team was questioning him (Sneed) about—hence, the two question marks reflecting questions being asked. The prosecutor's adjoining notes reflect two visits ("2X") by defense representatives—with notes about the two visits separated by a curving line.

Turning to the first visit, as shown by the note flagged with a red arrow above, Sneed's visitors were "women." As shown by the notes flagged with a blue arrow, that visit involved an investigator ("invest.") who may have been heavy set ("heavy set?"). As shown by the notes flagged by the green arrow, the defense representatives may have been involved in Glossip's earlier direct "appeal." And, finally, as shown by the notes flagged by the two black arrows, the women questioned Sneed about (1) whether he was "on lithium?" and (2) a "Dr[.] Trumpet?"—i.e., questioned by the women representing Glossip. Thus, read in context, the key words in the prosecutor's notes reveal that Sneed was recounting not what the prosecutor had independently learned (much less confirmed and knew) but rather questions Glossip's defense team was asking Sneed.

During oral argument in October, Glossip and the Oklahoma Attorney General both argued for setting Glossip's murder conviction aside. Today, the Supreme Court agreed, finding that the OCCA had misinterpreted federal law. The Court held that the Oklahoma courts had misinterpreted Napue v. Illinois, which became an underpinning for the Brady rule and explained that due process forbids prosecutors from "the knowing use of false evidence." But then today's opinion continues to make new factual findings the case for the first time on appeal. Very surprisingly, the Court held that remedy was not the standard remand for further proceedings but rather an automatic new trial for Glossip. The Court got it wrong—or, even more clearly, the Court ruled based on distorted record where the parties collusively concealed important information.

In the majority opinion, Justice Sotomayor specifically discussed the issues raised by my interpretation of the prosecutor's notes:

In an amicus brief, the Van Treese family argues that it was Glossip's counsel who asked Sneed about his lithium prescription, and that [the prosecutor's] notes reveal only that Sneed relayed those questions to [the prosecutor]. See Brief for Victim Family Members as Amici Curiae 7–22. That argument relies heavily on extra-record materials not properly before the Court, including a recent unsworn statement from [the prosecutor] adopting the family's interpretation of the notes. (The dissent, which criticizes the independent counsel for "impugning" the trial prosecutors' reputation, post, at 15, justifies its reliance on these materials by accusing the Oklahoma attorney general of "collusively exclud[ing]" them from the record, see post, at 42.) Nor would accepting the family's account change the Napue analysis. Whatever the impetus for the conversation, the family agrees that Sneed and [the prosecutor] discussed Dr. Trombka and lithium. The natural inference is that Sneed explained to [the prosecutor] the circumstances that led to his lithium use.

Several observations on this passage. First, and most notably, Justice Sotomayor merely flagged the dissent's position accusing the Oklahoma attorney general of "collusively exclud[ing] … highly relevant evidence from the record." Justice Sotomayor did not dispute that characterization's accuracy.

Second, Justice Sotomayor concluded that the materials I provided from the family would not "change" the Napue analysis, based on what she believes is the "natural inference" about a "conversation" that then ensued between the prosecutors and the witness (a conversation that is not memorialized in the prosecutor's notes).

This is a gobsmackingly inaccurate description of the materials that I presented. As recounted in a letter from both prosecutors in the case attached to my brief, what happened during the Sneed interview was that he recounted that Glossip's defense attorneys "asked him questions about lithium and Dr. Trumpet. The question marks after those two words indicate that the women asked him those questions." Van Treese Br. at 10a (reprinting letter from prosecutors). Contrary to the alleged "natural inference" from the notes, the notes' authors explain that Sneed was no discussing the "circumstances" surrounding Sneed's prescribed use of lithium—only the fact that the defense attorneys were asking about it.

Justice Sotomayor tried to support her "natural inference" with a reference to a jail medical record, which appeared to include information about Sneed's lithium prescription. But, as noted above, for prosecutors to violate Napue, they must "knowingly" use false evidence. Even assuming that the prison medical record showed that Sneed was prescribed lithium, that record did not show prosecutors "knowingly" used false testimony to the contrary. As the two prosecutors explained in a letter included in my brief to the court: "The two of us, in a combined over fifty-five years of prosecuting cases, have never seen a transport order like this document. The first time we saw this specific document was when it was attached to a defense filing in 2022," which (of course) was nearly two decades after Glossip's trial. The prosecutors could not have knowingly used testimony contrary to a record that they had never seen.

Justice Sotomayor also noted that Justice Thomas' dissent argued for a remand to the Oklahoma courts to provide "the Van Treese family [with] the opportunity to present its case." But, for Justice Sotomayor, this was not enough because "[t]he family has not requested an evidentiary hearing (or participation in one) at any stage before the OCCA and does not request that relief before this Court." (Op. at 27 n.11.) Her conclusion is obviously disappointing, particularly given that I filed a motion to participate in oral argument before the Court—a motion that the Court denied (without explanation) in favor of instead giving a Court-appointed amicus the opportunity to defend the judgment below. Moreover, the family's brief obviously asked the Court to simply affirm the judgment below. Once the Supreme Court rejected the family's overarching position, the family would clearly have preferred to have their factual arguments considered by the Oklahoma courts—rather than simply ignored as "extra-record" by the Supreme Court in its haste to command a new state court trial.

Justice Thomas' dissent (joined in full by Justice Alito and in part by Justice Barrett) highlighted numerous flaws in the majority's opinion. In this post, I will spotlight Justice Thomas' important discussion of my amicus brief for the victim's family. Justice Thomas explains how my brief advanced a perfectly plausible alternative reading of the notes in question:

Concluding that no new factual development is needed is particularly inappropriate given the alternative reading of the notes advanced by the Van Treese family in this Court. As discussed above, the family has argued that the supposed "smoking gun"—the notes from Box 8—in fact reflects Sneed's recollection of what defense counsel had asked him at two prior meetings. [Prosecutors] Smothermon and Ackley have likewise endorsed this interpretation, which casts serious doubt on Glossip's and the State's theory. If Sneed simply reported that he was asked about Dr. Trombka without admitting Dr. Trombka prescribed him lithium, Smothermon and Ackley would have had no reason to know that Dr. Trombka prescribed him lithium. And, the indication in Ackley's notes that Sneed apparently mentioned his "'tooth'" being "'pulled'" suggests that Sneed stood by his earlier story that he was mistakenly prescribed lithium when his tooth was pulled. (citations omitted).

For Justice Thomas, instead of the Supreme Court engaging in appellate fact-finding on a distorted record, the proper result would have been to send the case back to the Oklahoma courts for further consideration. Justice Thomas highlighted the "collusive" distortion of the record that the parties orchestrated in this case:

To the extent the Court insists it cannot endorse the family's theory because it relies on "extra-record materials not properly before the Court," ante, at 25, … that is because the parties collusively excluded this highly relevant evidence from the record in order to reach a predetermined outcome. The majority rewards this gamesmanship, and in so doing denies the victim's family the opportunity to present contrary evidence. (Dissent at 42 (emphasis added)).

Justice Thomas observed that the victim's family deserved its "day in court":

The "Government should turn square corners in dealing with the people." That command extends not only to criminal defendants, but also to their victims. "[C]onducting retrials years later inflicts substantial pain on crime victims," who must "relive their trauma and testify again," in this case 28 "years after the crim[e] occurred." The Oklahoma Constitution recognizes this interest by giving crime victims like the Van Treese family the right—"which shall be protected by law in a manner no less vigorous than the rights afforded to the accused"—"to be heard in any proceeding involving release, plea, sentencing, disposition, parole and any proceeding during which a right of the victim is implicated." Art. II, §34(A). Glossip, on the other hand, would suffer no prejudice from an evidentiary hearing in which the Van Treese family had the opportunity to present its case. If the evidence is as decisive as the majority believes, Glossip would still receive a new trial. There is no excuse for denying the Van Treese family its day in court. (citations omitted).

Justice Thomas decried how unfair it is for the Court to decide this case based on a collusively crafted and distorted set of facts:

After having bent the law at every turn to grant relief to Glossip, the Court suddenly retreats to faux formalism when dealing with the victim's family. The Court concludes that it need not honor the family's right to be heard because the family did not request an evidentiary hearing earlier in the proceedings. But, the family had no need to do so, since Glossip had conceded that "a hearing is necessary" for his claim to rise above the level of "speculation." And, before this Court, the Van Treese family has vigorously asserted its interests. The family filed the only brief opposing certiorari in this case. It filed a merits brief highlighting critical evidence that the parties sought to sweep under the rug. And, it filed a motion to participate in oral argument, which this Court denied. The majority's assertion that the family has sat on its rights is groundless. (Dissent at 43 (citations omitted).

Justice Thomas concluded his powerful dissent by chastising the majority for failing to consider the victim's family's interests: "[E]ven if the family had no formal right to be heard, any reasonable factfinder plainly could consider the account of the evidence that the family has brought to light, making the majority's procedural objections beside the point. Make no mistake: The majority is choosing to cast aside the family's interests. I would not."

In the back-and-forth between the majority and Justice Thomas, it will not be lost on the reader that the majority has no response to his observation that the parties (i.e., Glossip and the Oklahoma Attorney General) have "collusively excluded this highly relevant evidence from the record [about what the prosecutor's notes mean] in order to reach a predetermined outcome." As a result, for those who would cite this case as an example of trial prosecutors knowingly relying on false evidence, the case more accurately stands for the proposition that the Oklahoma Attorney General's Office and the defendant have succeeded, through "gamesmanship," in collusively distorting the record.

Commenting in a press release today on the "victory" he had obtained before the U.S. Supreme Court, Attorney General Drummond asserted that "[o]ur justice system is greatly diminished when an individual is convicted without a fair trial, but today we can celebrate that a great injustice has been swept away. I am pleased the high court has validated my grave concerns with how this prosecution was handled, and I am thankful we now have a fresh opportunity to see that justice is done."

From what I can see, General Drummond still has no explanation for why he "collusively excluded … highly relevant evidence from the record" to obtain his victory. Sadly, while the Attorney General is crowing about "justice being done," the victim's family may well be left with no remedy for his deceitful maneuver. It's a sad day for justice in this country when an attorney general can exclude highly relevant evidence and then win his case on a distorted record—leaving the victim's family to wonder why relevant facts about a murder trial held more than two decades ago can deceptively be swept under the rug.

One final note: The Court has sent the case back for a retrial. The evidence in this case is overwhelming. The family remains confident that when that new trial is held, the jury will return the same verdict as in the first two trials: guilty of first degree murder.

Update: For more legal analysis critical of today's ruling, see Kent Scheidegger's post here.

Correction: In my original post, I inaccurately described the Napue case as an "interpretation" of the Brady rule. As an alert reader (SMP0328) correctly points out, Brady was a later (and broader) decision, applying the same principles. I have corrected the post to reflect the timing.

The post Did Glossip and the Oklahoma Attorney General Collusively Conceal Evidence to Win Their U.S. Supreme Court Case? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Has Hill v. Colorado Already Been "Abandoned" Like Lemon?

[Did Kennedy v. Bremerton overrule the precedent on precedent from Rodriguez de Quijas?]

Justice O'Connor once explained that "no legal rule or doctrine is safe from ad hoc nullification by this Court when an occasion for its application arises in a case involving state regulation of abortion." (I think a similar principle applies to the Eighth Amendment; more on Glossip later.) In the lead-up to Dobbs, I listed a host of precedents in which the law was distorted to protect Roe. One such case was Hill v. Colorado. The Court upheld a "buffer" zone around an abortion clinic, which prevented people from expressing pro-life views. Hill was always inconsistent with the Court's other forum cases, but abortion was just too important.

In the wake of Dobbs, there have been several petitions urging the Court to overrule Hill. Indeed, local governments have attempted to manipulate the Court's jurisdiction to save the precedent. (I'm looking at you Westchester County!) But the Court has continued to deny those petitions.

Yesterday, the Supreme Court denied yet another case that sought to overrule Hill. In Coalition Life v. City of Carbondale, Justice Alito would have granted the petition, and Justice Thomas wrote a lengthy dissent from denial. Thomas repeated his usual refrain that Hill distorted First Amendment principles, and it is difficult to see what is left of Hill after Dobbs: "Hill's abortion exceptionalism turned the First Amendment upside down."

But Justice Thomas added a new spin on things. He explained that Hill has been eroded by recent cases, including McCullen v. Coakley, Reed v. Town of Gilbert, City of Austin, and (of course) Dobbs. Thomas writes, "If Hill's foundation was 'deeply shaken' before Dobbs, see Price, 915 F. 3d, at 1119, the Dobbs decision razed it." (Price v. City of Chicago was a Seventh Circuit decision by Judge Sykes, that then-Judge Barrett joined).

Thomas then draws an analogy between Hill v. Colorado and Lemon v. Kurtzman:

This trajectory calls to mind the story of Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U. S. 602 (1971), which had created a three-part test to determine whether a law violated the Establishment Clause. While this Court had not by any one statement overruled Lemon, for many years it either "expressly declined to apply the test" or "simply ignored it." American Legion v. American Humanist Assn., 588 U. S. 29, 49 (2019) (plurality opinion) (collecting cases). We were never shy about Lemon's "shortcomings" and "daunting problems." 588 U. S., at 49, 51. And, we eventually faulted lower courts for failing to notice that the "'shortcomings' associated with th[e] 'ambitiou[s],' abstract, and ahistorical" Lemon test had "bec[o]me so 'apparent' that this Court long ago abandoned" it. Kennedy v. Bremerton School Dist., 597 U. S. 507, 534 (2022) (second alteration in original). In other words, we explained, Lemon had long been dismantled by our precedents, and lower courts should have recognized its demise. Given that prior to Kennedy, a decision of the Court had never outright condemned Lemon as a "distort[ion]," Dobbs, 597 U. S., at 287, and n. 65, Hill's abandonment is arguably even clearer than Lemon's.

Woah! Should courts recognize that Hill v. Colorado has already met its demise? Does Justice Thomas think that lower courts now have a green light to treat Hill v. Colorado as "abandoned"? To be sure, Rodriguez de Quijas v. Shearson/American Express Inc. (1989) suggests that the answer is clearly no: "If a precedent of this Court has direct application in a case, yet appears to rest on reasons rejected in some other line of decisions, the Court of Appeals should follow the case which directly controls, leaving to this Court the prerogative of overruling its own decisions." But did Kennedy v. Bremerton abrogate Rodriguez de Quijas? To be sure, plenty of Courts disregarded Baker v. Nelson in the wake of Windsor, but the precedential value of Baker was always questionable from the outset. In any event, I think Dobbs demonstrated that precedents on precedent are not entitled to stare decisis value. So maybe the Court has moved beyond Rodriguez de. Quijas?

Of course, Justice Thomas wrote a solo dissent. No one joined him. Even Justice Alito, who would have granted the petition, did not join Thomas's opinion.

I think it is unlikely the Court will ever formally overrule Hill. Despite Thomas's appeal to Justice Barrett, she did not budge. And really, is there any doubt why the number of summary reversals, as well as cert grants, are down? It is Justice Barrett. I made this point nearly a year ago:

Justice Kavanaugh, by contrast, has signaled that he is more open to cert grants. I've taken notice of the random dissents from denial of cert on the order list for low-profile cases. Those dissents show that he carefully scrutinizes all of the petitions, and is looking for issues to grant. By my count, Barrett has only dissented from the denial of certiorari once in Waleski v. Montgomery, McCracken, Walker & Rhoads (2023). This case presented a nerdy FedCouts question about "hypothetical jurisdiction"--not exactly something of national importance. (She joined Justice Thomas's dissent, along with Justice Gorsuch.) In most cases, if Barrett is willing to grant, there are almost certainly three more votes to join her.

See also this post.

Nothing has changed since 2024.

The post Has Hill v. Colorado Already Been "Abandoned" Like Lemon? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Authorship Predictions for the October Sitting

[It is never too early to make predictions!]

During the October sitting, nine cases were argued. With this lineup, it is likely that each Justice will have one opinion. Five of those cases have already been decided.

Justice Kavanaugh wrote Williams v. Reed. Justice Kagan wrote Royan Canin. Chief Justice Roberts wrote Lackey v. Stinnie. Justice Sotomayor wrote Glossip v. Oklahoma. Justice Jackson wrote Bouarfa v. Mayorkas.

Four cases remain to be decided: VanDerStock, Medical Marijuana v. Horn, Bufkin v. McDonough, and San Francisco v. EPA.

Back in January, I offered this prediction:

Fourth, we can already start to make predictions about the assignment of cases. There were nine cases argued during the October sitting. Presumably, each Justice will have one case from that sitting. Two cases have been decided so far from that sitting. Justice Kagan wrote Royal Canin, and Justice Jackson wrote Bouarfa, an immigration case. If I had to guess, the top two candidates to write Royal Canin would be the two procedure professors: Kagan or Barrett. Kagan got Royal Canin, which was argued on October 7. VanDerStock was argued on October 8. The only liberal left to write is Justice Sotomayor. And I do not think the Chief would give her that case. I have a sinking feeling Barrett has VanDerStock, which is at bottom a statutory interpretation case. (I say sinking because I was counsel on that case, and attended oral argument.) Then again, we may never know how that case turns out, if the Trump ATF and DOJ take a new position. If that happens, we can check at the end of the term if Barrett doesn't write an opinion for October.

I think it is even more likely that Justice Barrett has VanDerStock.

That leaves Justices Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch for the remaining three cases. My uninformed speculation: Gorsuch has Medical Marijuana (he is from the Mile "High" City and he has written opinions about truckers before), Thomas has Bufkin, the Veterans Claim case, and Alito has San Francisco.

The post Authorship Predictions for the October Sitting appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "A Woman Made Her AI Voice Clone Say 'Arse.' Then She Got Banned"

From the MIT Technology Review (Jessica Hamzeou):

Both Joyce Esser, who lives in the UK, and Jules Rodriguez, who lives in Miami, Florida, have forms of motor neuron disease—a class of progressive disorders that result in the gradual loss of the ability to move and control muscles….

AI is bringing back those lost voices. Both Jules and Joyce have fed an AI tool built by ElevenLabs recordings of their old voices to re-create them. Today, they can "speak" in their old voices by typing sentences into devices, selecting letters by hand or eye gaze…. It's been a remarkable and extremely emotional experience for them—both thought they'd lost their voices for good….

[But at one point,] Joyce typed a message for her voice clone to read out: "Come on, Hunnie, get your arse in gear!!" She then added: "I'd better get my knickers on too!!!"

"The next day I got a warning from ElevenLabs that I was using inappropriate language and not to do it again!!!" Joyce told me via email (we communicated with a combination of email, speech, text-to-voice tools, and a writing board)…. "… [B]ecause the next day a human banned me!!!!" …

Joyce contacted ElevenLabs, who apologized and reinstated her account. But it's still not clear why she was banned in the first place….

Thanks to Jordan Brown for the pointer.

The post "A Woman Made Her AI Voice Clone Say 'Arse.' Then She Got Banned" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "Certain Phrases, Including 'Free Hong Kong' and 'Tiananmen Square,' Were Not Allowed" for Marvel Gamers

From N.Y. Times (German Lopez):

Marvel Rivals is one of the biggest video games in the world. Since its launch in December, more than 40 million people have signed up to fight one another as comic book heroes like Iron Man and Wolverine. {With Marvel Rivals, Disney licensed its intellectual property for the game.}

But when players used the game's text chat to talk with teammates and opponents, they noticed something: Certain phrases, including "free Hong Kong" and "Tiananmen Square," were not allowed.

While Marvel Rivals is based on an iconic American franchise, it was developed by a Chinese company, NetEase Games. It has become the latest example of Chinese censorship creeping into media that Americans consume.

You can't type "free Tibet," "free Xinjiang," "Uyghur camps," "Taiwan is a country" or "1989" (the year of the Tiananmen Square massacre) in the chat. You can type "America is a dictatorship" but not "China is a dictatorship." Even memes aren't spared. "Winnie the Pooh" is banned, because people have compared China's leader, Xi Jinping, to the cartoon bear.

The restrictions are largely confined to China-related topics. You can type "free Palestine," "free Kashmir" and "free Crimea." …

The post "Certain Phrases, Including 'Free Hong Kong' and 'Tiananmen Square,' Were Not Allowed" for Marvel Gamers appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers