Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 119

April 21, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Brief from Prof. Justin Driver (Yale) and Me in School Curriculum / Religious Opt-Out Case

["This Court should not announce an opt-out right for religious objectors under the Free Exercise Clause that its precedents would foreclose for students objecting to public-school curricula under the Free Speech Clause."]

We argue, in an amicus brief filed in Mahmoud v. Knight (now pending before the Supreme Court), that the Free Exercise Clause doesn't secure a presumptive right to opt out of K-12 public school curriculum elements to which the parents or children have a religious objection. Many thanks to I. Rodgin Cohen, Amanda Flug Davidoff, Daniel J. Richardson, and Harrison J. Tanzola (Sullivan & Cromwell LLP), who wrote the brief on our behalf. Here's the Summary of Argument:

Petitioners ask this Court to hold that parents have a constitutional right to interfere with the routine curricular decisions of public schools. Whether this Court answers that question by applying its existing free-exercise precedents or—as members of this Court have recently suggested—by considering analogies to free-speech doctrine, see Fulton v. City of Phila., 593 U.S. 522, 543 (2021) (Barrett, J., concurring); id. at 565 n.28 (Alito, J., concurring in the judgment), the answer is the same: The First Amendment does not shield public-school students from the mere exposure to ideas that conflict with their personal views, whether secular or religious.

Every day, thousands of public schools throughout the United States make countless decisions about the best way to educate their students. Those decisions reflect the input of educators, parents, and local communities. They thus incorporate competing views about both the materials that should be included in public-school curricula and the role of public education in civil society. In a country as diverse as the United States, those decisions also often expose students to ideas that may be in tension with their deeply held beliefs.

This Court has developed an extensive body of law that balances the needs of the public-school system against the free-exercise rights of students and parents. These decisions prevent public schools from espousing or indoctrinating religious views, require schools to accommodate students' private religious practices, and let parents educate their children outside the public-school system altogether. At the same time, they also recognize the importance of local control over education and the harms that can arise from judicial interference in curricular decision-making. Taken together, this Court's precedents have established a stable framework—one that has allowed religious exercise to flourish on and off school grounds, but without inhibiting the ability of local communities to make decisions about public education and to expose public-school students to a wide variety of ideas.

Petitioners' suit would upset that balance. In this case, the Montgomery County Public School Board approved a set of books for its English curriculum that include LGBT characters. The Board added these books to "assist students with mastering reading concepts" and to teach respect for other students. Petitioners challenged MCPS's decision, arguing that the Free Exercise Clause requires the county either to remove the books or to accommodate opt-outs for any student who has a religious objection to reading them. In advancing that claim, Petitioners did not contend that the books espoused any religious or anti-religious view, nor did they show that the Board included the books to coerce students into adopting any particular viewpoint. Instead, they argued that merely introducing students to books in tension with their religious faith violated the Free Exercise Clause.

Petitioners' sweeping opt-out theory is inconsistent with free-exercise law and would undermine the educational system. For decades, this Court has recognized that students do not surrender their constitutional rights at the schoolhouse gate. But it has also explained that the protections of the First Amendment must be tailored to the unique demands of the school environment, and has cautioned against constitutional theories that would displace the "vital national tradition" of local control over education.

Applying those decisions, lower courts have consistently (and correctly) held that the Free Exercise Clause does not allow parents to override routine public-school curricular decisions. As these courts have recognized, "[p]ublic schools often walk a tightrope between the many competing constitutional demands made by parents, students, teachers, and the schools' other constituents." When weighing those demands, our constitutional system vests authority in "the normal political processes for change," rather than the federal courts.

That result is not unique to free exercise. In recent years, members of this Court have suggested that the Free Exercise Clause should be understood in light of other First Amendment freedoms. Justice Barrett's concurrence in Fulton suggested that the meaning of free exercise may be informed by how "this Court[]" has treated "other First Amendment rights-like speech and assembly." And Justice Alito's Fulton opinion argued that "the phrase 'no law' applies to the freedom of speech and the freedom of the press, as well as the right to the free exercise of religion, and there is no reason to believe that its meaning with respect to all these rights is not the same."

Examining how "other First Amendment rights" apply to school curricula confirms that the decision below was correct. This Court has long held that schools can expose students to materials on various subjects without infringing the free-speech rights of students and parents. And federal courts have long rejected claims (like Petitioners') that would either require student-specific opt-outs or empower individual parents to dictate educational decisions for the entire school. This Court should not announce an opt-out right for religious objectors under the Free Exercise Clause that its precedents would foreclose for students objecting to public-school curricula under the Free Speech Clause.

The practical implications of Petitioners' opt-out theory provide another reason for caution. Were this Court to adopt Petitioners' view, public schools would be forced to either (i) offer student-specific instruction every time a parent identifies a potential conflict between the public-school curriculum and their religious faith, or (ii) develop a curriculum so anodyne that it aims to avoid even the slightest risk of exposing students to ideas that may conflict with any conceivable religious belief-a task that would almost certainly prove impossible in practice.

Such a result would be both unworkable and undemocratic. Parents would have the right to flyspeck curricula in a vast range of academic subjects, as they have already tried to do. See, e.g., Fleischfresser v. Directors of Sch. Dist. 200 (7th Cir. 1994) (discussing a free-exercise challenge to books that reference "wizards, sorcerers, [and] giants"). And schools would be discouraged from providing the education they believe to be most valuable, in favor of making choices that-they hope, but can never know-would provoke relatively few parents to opt out.

The Court of Appeals' decision correctly applied free-exercise law, aligned with other First Amendment doctrines, and honored the importance of local control over education. This Court should affirm….

If you're interested, you can read the whole thing here and many more briefs on both sides .

The post Brief from Prof. Justin Driver (Yale) and Me in School Curriculum / Religious Opt-Out Case appeared first on Reason.com.

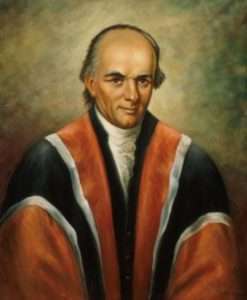

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: April 21, 1800

4/21/1800: Justice Alfred Moore takes judicial oath.

Justice Alfred Moore

Justice Alfred MooreThe post Today in Supreme Court History: April 21, 1800 appeared first on Reason.com.

April 20, 2025

[Ilya Somin] Free Press Symposium on "Is Donald Trump Breaking the Law?"

[The degree of agreement among participants with major ideological diferences is striking.]

(Lex Villena; Midjourney)

(Lex Villena; Midjourney) Today, the Free Press published a symposium on "Is Donald Trump Breaking the Law?"

Participants include (in addition to myself), several prominent constitutional law scholars and legal commentators : Jonathan Adler (Case Western/Volokh Conspiracy co-blogger), Aziz Huq (University of Chicago), Larry Lessig (Harvard), Andrew McCarthy (National Review), Michael McConnell (Stanford), Ed Whelan (Ethics and Public Policy Center), and yours truly.

The editors of FP summarize the contributions, as follows:

The consensus is striking—and perhaps surprising, given the ideological diversity of these contributors. All agreed that the president's legal tactics reflect a dangerous willingness to ignore statutory and constitutional constraints—and that he must be reined in quickly.

Speaking for myself alone, I think I have never before been part of an ideologically diverse symposium on a contentious topic where I agreed with over 90% of what the other participants said. But I do here, despite major ideological differences with all the others (except, probably, Adler). If I have a disagreement, it may be with Larry Lessig's argument that the best analogy to Trump's behavior is that of Mafia bosses. I think that comparison is a bit unfair to the Mafiosi, and the better analogy is to various nationalist authoritarians and wannabe authoritarians. But I do agree that what Lessig says is illegal is in fact so.

It's perhaps notable that two of the contributors (Huq and Lessig) are far to the left of me, and two others (McCarthy and Whelan) are far to the right. McConnell is also substantially more conservative than I am, but probably to a lesser degree than McCarthy and Whelan.

Skeptics can argue that FP cherry-picked the participants. But it's worth noting that Free Press is generally viewed as a right-leaning "anti-woke" publication. They've even been criticized for being excessively friendly to the MAGA movement and overly tolerant of its excesses.

Here's an excerpt from my own contribution:

The second Trump administration is trying to undermine the Constitution on so many fronts that it's hard to keep track. But three are particularly dangerous: the usurpation of Congress's spending power; unconstitutional measures against immigration justified by bogus claims that the U.S. is under "invasion"; and assertions of virtually limitless presidential power to impose tariffs….

Trump has claimed the power to "impound" federal funds expended by Congress, and to impose conditions on federal grants to state governments and private entities that Congress never authorized. The Constitution gives the power of the purse to Congress, not the president….

On immigration, Trump has issued an executive order claiming illegal migration amounts to an "invasion," thereby authorizing him to suspend most legal migration. The order is at odds with overwhelming evidence indicating that, under the Constitution, "invasion" means an "operation of war" (as James Madison put it), not mere illegal border crossing or drug smuggling. The invasion order threatens not only immigrants, but U.S. citizens….

Similar bogus invocations of "invasion" have been cited by Trump to justify invoking the Alien Enemies Act of 1798—legislation that can only be used in the event of war, "invasion," or "predatory incursion"—to deport Venezuelan migrants without due process to imprisonment in El Salvador….

The administration's claims that courts are powerless to order the return of illegally deported and imprisoned people menace not only immigrants, but American citizens. Under Trump's logic, they, too, could be deported and imprisoned abroad, and courts could not order their return.

Finally, Trump has usurped congressional authority over international commerce to impose his massive "Liberation Day" tariffs, thereby starting the biggest trade war since the Great Depression, and gravely damaging the U.S. economy….

The post Free Press Symposium on "Is Donald Trump Breaking the Law?" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: April 20, 2010

4/20/2010: United States v. Stevens decided.

The post Today in Supreme Court History: April 20, 2010 appeared first on Reason.com.

April 19, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Justice Alito Dissents: "Both the Executive and the Judiciary have an obligation to follow the law."

[Justice Alito also questions whether the Court even had jurisdiction to act.]

Saturday evening, I published three posts on A.A.R.P. v. Trump. Around midnight eastern time, Justice Alito issued his dissent, which was joined only by Justice Thomas. The dissent begins: "Shortly after midnight yesterday, the Court hastily and prematurely granted unprecedented emergency relief." He is correct.

Justice Alito lists seven bullets which demonstrates why this order was problematic. The first bullet argues that it is unclear the Court had jurisdiction:

It is not clear that the Court had jurisdiction. The All Writs Act does not provide an independent grant of jurisdiction. See 28 U. S. C. §1651(a) (permitting writs "necessary or appropriate in aid of " a court's jurisdiction); Clinton v. Goldsmith, 526 U. S. 529, 534–535 (1999) ("the express terms" of the All Writs Act "confine the power of [a court] to issuing process' in aid of ' its existing statutory jurisdiction; the Act does not enlarge that jurisdiction" (quoting §1651(a)). Therefore, this Court had jurisdiction only if the Court of Appeals had jurisdiction of the applicants' appeal, see §1254 (granting this Court jurisdiction to review "[c]ases in the courts of appeals"), and the Court of Appeals had jurisdiction only if the supposed order that the applicants appealed amounted to the denial of a preliminary injunction. See §1292(a)(1).

I've received a number of emails about my Marbury post. I'll offer a few points in response. The All Writs Act permits the Court to take actions in aid of its jurisdiction, and even in aid of its future jurisdiction. But, as Justice Alito notes, the All Writs Act does not, by itself, grant the Court new statutory jurisdiction. The Court still must have statutory jurisdiction from some other basis. The usual basis is where there is a judgment that is appealable under Section 1292. In some cases, the Court have construed a TRO as, in effect, a preliminary injunction, thus permitting the Court to intervene. But in A.A.R.P., the District Court did not rule at all, one way or the other. There is a doctrine where the "constructive" denial of a TRO is considered a ruling. But as Judge Ramirez pointed out, the district court was given about 42 minutes to rule. There is no sense this was a "constructive" denial.

Perhaps the ACLU might argue that the question of whether there is a "constructive" denial is a merits question. But I think it has to be jurisdictional, and that is what the Fifth Circuit concluded. If the Supreme Court wanted to issue any relief, it would have to satisfy itself there was a constructive denial, which would afford it some sort of statutory jurisdiction. I doubt any such finding was made. The Court fell for the ACLU's petition hook, line, and sinker.

It's not at all clear to me that the Supreme Court had any appellate statutory jurisdiction in this case. And if it was not exercising an appellate statutory jurisdiction, then how did the Court issue an order to the "government" (however defined)? If in fact the All Writs Act permits the Supreme Court to assume statutory jurisdiction over a future appeal, and issue an injunction, when in fact the District Court was never even given a chance to rule, then the All Writs Act may have some Marbury problems.

Has the Supreme Court ever issued an injunction or mandamus in a case where there is no ruling from any lower court? (I am not talking about cases of constructive denial.) I would wager the answer is no, but maybe someone knows of these cases. I am happy to post an update.

Justice Alito's second and third bullets focus on whether the ACLU complied with the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure Rule 8(a)(1)(A) and Supreme Court Rule 23.3 about emergency relief. They didn't. These sorts of procedural rules only seem to matter when the Court wants to deny relief.

Alito does include a piece of information that hasn't been made public:

When this Court rushed to enter its order, the Court of Appeals was considering the issue of emergency relief, and we were informed that a decision would be forthcoming.

Based on my calculations, the Fifth Circuit ruled within a few minutes of the Supreme Court. The Fifth Circuit's order was dated April 18. It was issued around midnight central time, which would be around 1:00 a.m. ET. The Supreme Court's order was issued around 1:00 a.m. ET. It isn't clear which happened first. I asked the Clerk of the Fifth Circuit for clarification, which should be a matter of public record. But now we learn that Chief Justice Roberts knew the Fifth Circuit was going to rule, but just didn't give a damn to wait. Maybe he thought it was easier to try to rule first, and avoid having to make any ruling on anything?

Justice Alito's fourth bullet explains the problems with granting ex parte relief, where there are only briefs from one side.

Justice Alito's fifth bullet attacks another ruling issued late at night: South Bay:

The papers before us, while alleging that the applicants were in imminent danger of removal, provided little concrete support for that allegation. Members of this Court have repeatedly insisted that an All Writs Act injunction pending appeal may only be granted when, among other things, "the legal rights at issue are indisputably clear and, even then, sparingly and only in the most critical and exigent circumstances." South Bay United Pentecostal Church v. Newsom, 590 U. S. ___, ___ (2020) (ROBERTS, C. J., concurring in denial of application for injunctive relief ) (slip op., at 2) (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting S. Shapiro, K. Geller, T. Bishop, E.Hartnett, D. Himmelfarb, Supreme Court Practice§17.4, p. 17–9 (11th ed. 2019));

In my earlier post, I speculated:

Can you imagine if the Supreme Court had bypassed all lower courts, and enjoined an emergency COVID regulation twenty-four hours after a district court TRO was filed?

Does everyone remember the South Bay "super precedent"? During the pandemic, there were actual imminent injuries by American citizens who sought to pray on holidays. But Chief Justice Roberts took his time, and ruled against people of faith for months at a time. It wasn't until Justice Barrett's confirmation that this tide turned. (I am convinced she regrets that early vote.) By contrast, the Court issues unprecedented orders to ensure that alleged gang members, who are in this country illegally, cannot be deported. I'm glad that the Chief has his priorities straight. This is what Trump would call an 80/20 issue.

Justice Alito's sixth bullet references a hearing before Judge Boasberg on a Saturday.

Although this Court did not hear directly from the Government regarding any planned deportations under the Alien Enemies Act in this matter, an attorney representing the Government in a different matter, J. G. G. v. Trump, No. 1:25–cv–766 (DC), informed the District Court in that case during a hearing yesterday evening that no such deportations were then planned to occur either yesterday, April18, or today, April 19.

Judges in the Beltway apparently are always on call to hold emergency hearings whenever the ACLU asks for one. It is unclear why Judge Boasberg is doing anything with these cases. The Supreme Court found he lacks venue and the D.C. Circuit stayed his special prosecutor frolick. Still, even if Boasberg denied relief, he is still demanding concessions from government lawyers.

The seventh bullet points out an obvious argument: the Court has never held that habeas can be used to certify a class, and the District Court never certified a class. The Supreme Court cannot exercise Rule 23 powers on the fly.

Although the Court provided class-wide relief, the District Court never certified a class, and this Court has never held that class relief may be sought in a habeas proceeding.

Justice Alito issues a challenge to his fellow members: I couldn't join this opinion, so why did you?

In sum, literally in the middle of the night, the Court issued unprecedented and legally questionable relief without giving the lower courts a chance to rule, without hearing from the opposing party, within eight hours of receiving the application, with dubious factual support for its order, and without providing any explanation for its order. I refused to join the Court's order because we had no good reason to think that, under the circumstances, issuing an order at midnight was necessary or appropriate.

The conclusion is a shot at J. Harvie Wilkinson:

Both the Executive and the Judiciary have an obligation to follow the law. The Executive must proceed under the terms of our order in Trump v. J. G. G., 604 U. S. ___ (2025) (per curiam), and this Court should follow established procedures.

Amen. The obligation cannot only be on Trump; the Court must obey the law as well. The more Chief Justice Roberts issues decisions like this, the more his precious "legitimacy" withers. I made a similar point here:

In a stress test, the Justices of the Supreme Court failed. In the same breath that Judges like J. Harvie Wilkinson wax poetic about the executive branch behaving lawlessly, the highest court in the land does no better.

Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas are national treasures.

Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh did not join this dissent. I see a redux of the tax return cases, where the clearly agreed with the dissenters but could not be seen ruling for Trump. As for Justice Barrett, I think we can finally bury the "process formalism" defense. There are so many procedural reasons why she should have dissented here. But she did not, without any explanation. We can't read an opinion that does not exist; much like the Supreme Court cannot review a decision that does not exist.

The post Justice Alito Dissents: "Both the Executive and the Judiciary have an obligation to follow the law." appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Process Formalism In Texas But Not At SCOTUS

[Kudos to Judge Ramirez who understands how the rules of civil and appellate procedure operate.]

For much of the last five years, the fine federal judges of Texas were slandered and maligned. They were called rogue, partisan hacks. Egged on by pundits on social media, these judges were targeted for non-stop attacks. Their chambers were blitzed with calls. They received countless misconduct complaints. Billboards were plastered with their faces. They were subject to repeated death threats, which led to criminal indictments. This conduct was far worse than any pizzas delivered to judges. How did the federal judiciary respond to these actions? By trying to ram down an illegal rule to take away their cases. And the threats were met with silence.

The reality is very different. For sure, plaintiffs forum shopped, but the Biden Administration never argued that venue was improper. And when these judges issued national injunctions or vacaturs, they stayed their rulings to permit the government to take a timely appeal. The Fifth Circuit moved promptly, and decided cases on its emergency docket to permit a timely appeal to the Supreme Court. It is fair to criticize these rulings on their substance, but over the four years of the Biden Administration, I think Texas judges largely followed fair procedures.

The second Trump administration has brought on a different wave of problems. District judges have permitted suits against the federal government for damages that should clearly have been brought in the Court of Federal Claims. Habeas actions brought on the east coast should have clearly been brought in Texas where the prisoners were confined. Actions seeking reinstatement of federal employees should have clearly been brought in the MSPB and other civil service forums. Judges have certified class actions during ex parte TRO hearings without any regard for Rule 23. And so on.

At every instance, judges in these cases abandoned any pretense of process formalism. Even as they denied Trump the presumption of substantive regularity, courts themselves abandoned any preseumption of procedural regularity. Judge Boasberg is perhaps the most egregious repeat offender. On a Saturday afternoon hearing, he told the ACLU lawyers to restyle their habeas case as an APA case to avoid venue problems, and immediately certified a class, and ordered the executive branch to turn around planes. Even after the Supreme Court gave him an easy out by finding he lacked venue, he is still going down the road to appoint a truly independent special prosecutor who can assert absolute authority over the executive branch. Again, Boasberg may be right or wrong about the substance, but procedurally, he is way out of his lane. The D.C. Circuit administratively stayed Boasberg's order by a 2-1 vote (Katsas and Rao, with Pillard dissenting). Let's see if that holds up.

By any procedural measure, the judges of Texas have behaved far better than the judges on the Amtrak Corridor. This background brings me to the latest installment of the emergency docket, A.A.R.P. v. Trump.

Judge Hendrix cannot be faulted. He moved with remarkable dispatch on a compressed timeline with a very complex case. The ACLU only gave him forty-two minutes to rule, even as he promisd to rule by the following day. You might say, well someone had to stop the planes? The federal judiciary does not work for the ACLU. There are many important cases on the docket. Indeed, it seems that Judge Hendrix had a criminal case that week. Generally, as any district court law clerk can tell you, criminal cases always take precedents over civil matters. (Whenever lawyers called to ask about the status of a civil case, I would parrot that line.) Judges cannot be expected to rule on incredibly complex cases, without waiting for the other side to reply. That sort of knee-jerk reaction would be the anthesis of reasoned decision-making. Remember, courts cannot solve all of society's ills. Some problems can only be resolved through the political process.

The Fifth Circuit cannot be faulted. They only had the case for a few hours before the ACLU ran to the Supreme Court. And the panel managed to put together a one-page order denying relief. This analysis, which was done without the benefit of any government briefing, is also emphatically correct.

Petitioners' opposed motion for a temporary administrative stay and an injunction pending appeal is DENIED as premature. "A court of appeals sits as a court of review, not of first view." Zaragoza v. Union Pacific Railroad Company, 112 F.4th 313, 322 (5th Cir. 2024) (cleaned up). That principle dictates our ruling today. Just yesterday, the district court entered an order indicating that "[t]he government states that authorities will not remove the petitioners during this litigation, and it will alert the Court if that changes." If Petitioners are concerned that Respondents' position has changed, they should have litigated these concerns before the district court in the first instance. We do not doubt the diligence and ability of the respected district judge in this case to act expeditiously when circumstances warrant. Petitioners insist that they tried to proceed before the district court in the first instance, and that the district court simply "refus[ed] to act." But the district court's order today indicates that Petitioners gave the court only 42 minutes to act—and did not give Respondents an opportunity to respond. The appeal is DISMISSED for lack of subject matter jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1291(a)(1), for substantially the reasons stated in Judge Ramirez's concurrence.

This is far more considered judgment than the Supreme Court gave to the issue.

Moreover, Judge Irma Carrillo Ramirez wrote a two paragraph concurrence under exceptionally tight circumstances:

Nevertheless, "what counts as an effective denial is contextual— different cases require rulings on different timetables." In re Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce, 100 F.4th 528, 535 (5th Cir. 2024). "District courts have wide discretion in managing their docket, and they do not necessarily deny a motion by failing to rule on a parties' requested timeline." Id. Here, the petitioners filed a motion for a temporary restraining order just after midnight on April 18, 2025. Around noon the next day, they filed a motion seeking a status conference and informing the district court that they would construe its failure to act within 42 minutes as a constructive denial of their motion. The ensuing appeal, after the district court failed to meet this unreasonable deadline, divested the district court of jurisdiction. It was therefore unable to complete its review of the filings, after affording the government an opportunity to respond, and issue rulings by noon on April 19, 2025, as it had planned. Although the declarations fully reflect the need for urgency, we cannot find an effective denial of injunctive relief based on the district court's failure to issue the requested ruling within 42 minutes. The appeal is dismissed for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1291(a)(1).

Kudos to Judge Ramirez. She previously served as a Magistrate Judge, and has a wealth of experience in the intricacies of trial court proceedings. The Supreme Court, and its two former district court judges, should know better.

Maybe the ACLU would have preferred if the Fifth Circuit summarily denied relief without putting out any opinion. That way the ACLU could take the case to the Supreme Court without delay. Maybe the Supreme Court does not even care what the Fifth Circuit has to say about these matters. If the Justices did, they could have waited a few hours before administratively staying the executive branch's actions. But process matters. Here, the fine judges of Texas illustrated process formalism. The members of the Supreme Court majority did not. Instead, they ignored the foundational principles of Marbury v. Madison and issued an order in the absence of appellate jurisdiction.

I wonder if the Supreme Court, when it decided J.G.G. v. Trump, thought through the next step. What would happen if the Fifth Circuit did not bend procedural rules like the D.C. Circuit did? The Supreme Court's ruling on venue punted the inevitable clash with the real process formalists.

My friend Mike Fragoso aptly noted the "excellent application of process formalism by Biden appointee, Irma Ramirez." He added, "too bad the Supreme Court' didn't heed to it."

Excellent application of process-formalism by Biden appointee, Irma Ramirez. Too bad the Supreme Court didn't take heed to it. https://t.co/yUClN0eP7P pic.twitter.com/S7hftMcTvz

— Mike Fragoso (@mike_frags) April 19, 2025

I share Mike's frustration. But some people on the Supreme Court did heed to it: Justices Alito and Thomas. At least one, and probably all three, of the Trump appointees, disregarded process formalism. (We'll see if anyone else joins Alito's imminent dissent.) As I've written before, for Justice Barrett, process matters except when the case comes from the Fifth Circuit. Here is your daily reminder that President Trump could have filled all three of his vacancies with judges from Texas.

Soon enough, A.A.R.P. will come back to the Court in the normal course. The Justices will never have to acknowledge how flawed this order was. Justice Alito will issue a dissent, as promised. But it will not make a difference. In a stress test, the Justices of the Supreme Court failed. In the same breath that Judges like J. Harvie Wilkinson wax poetic about the executive branch behaving lawlessly, the highest court in the land does no better.

I've long said that Chief Justice Roberts thinks about law in terms of newspaper headlines. "Supreme Court upholds Affordable Care Act" matters far more than the nuances of the Tax Anti-Injunction Act or the apportionment requirement of the Direct Taxes Clause. Roberts is proud to disavow being an originalist, but I think the reality is far worse. He is not a legalist. More often not, the law will take a backseat where Roberts thinks that there is some higher purpose the Court must serve in the moment.

The Court's statement (and it is not an order) in A.A.R.P. v. Trump illustrates this principle clearly. The headlines all report that "Supreme Court blocks removal of aliens by a 7-2 vote." But the press is utterly unconcerned with whether the Court even had jurisdiction to do so. Indeed, to the extent the reporters said anything, they unquestionably accepted the ACLU's position that the district court's failure to immediately rule on a motion warranted immediate intervention by the Supreme Court. How many of these reporters ever spent a day in district court, where preliminary injunction motions sometimes sit pending for weeks or months. The inferior courts performed with exemplary swiftness here.

I'll close with my common refrain. John Roberts is ill equipped to keep the Court away from an actual constitutional crisis. At this point, he is squirming in a pit of quick sand. The more he flails his arms, the quicker he will sink. Anyone who reaches out to the Chief will descend just the same.

The post Process Formalism In Texas But Not At SCOTUS appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] The Procedural Posture of A.A.R.P. v. Trump

[The Fifth Circuit and SCOTUS ruled at approximately the same time.]

I wrote a short post about A.A.R.P. v. Trump. Here, I will walk through the complex procedural posture of this case. I will do my best to lay out it clearly, and offer commentary at the end.

In the wake of J.G.G. v. Trump, district courts in Texas have asserted jurisdiction over alleged gang members who are slated for removal to El Salvador. Some of these aliens are currently being held in Abilene, Texas. Judge James Wesley Hendrix keeps his chambers in Lubbock, but draws cases from the Abilene Division of the Northern District of Texas.

On April 16, 2025 the ACLU filed suit on behalf of A.A.R.P and W.M. in the Abilene Division. They sought an ex parte TRO, alleging that the federal government planned to imminently remove the aliens. The government filed a reply later that day. On April 17, 2025, Judge Hendrix denied the TRO on the grounds that the removal was not imminent. That evening, counsel for the ACLU left a voicemail with the court about the case. Later that evening, the court ruled that any emergency relief must be sought on the docket. On April 18, at 12:34 a.m., the ACLU sought a second emergency TRO. Under a prior order, the government had twenty-four hours to respond. The Court noted the case "raised a series of complicated questions" and "believed that 24 hours was an appropriate time" to respond. Moreover, Friday was (for those who may not have known) Good Friday, and many people simply were not available to work that day. (We will see if the ACLU brings an Establishment Clause claim against the judge for citing a religious holiday to justify a delay.) Judge Hendrix said he would rule by Saturday, April 19. But he would never be given the chance to rule.

The ACLU filed another motion for an emergency immediate status conference at 12:48 p.m. CT. The motion stated that if the government did rule by 1:30 p.m.--forty-two minutes later--the ACLU would seek emergency relief from the Fifth Circuit. Judge Hendricks did not rule on the motion within forty-two minutes. The ACLU sought an appeal. But by filing an appeal, the ACLU divested Judge Hendricks of jurisdiction to proceed, and the chance to rule.

At this point, the timeline gets fuzzy, as ECF does not track the precise times when motions are docketed. But, as best as I can tell, several hours after the 1:30 p.m. deadline the case arrived at the Fifth Circuit. The ACLU requested an immediate ruling from the Fifth Circuit. Under the usual practice, when an emergency case arrives to the Fifth Circuit, the clerk assigns it a docket number, and it is assigned to a randomly drawn emergency panel. There is no reason to think the judges on this panel were tracking the case, let alone familiar with the complex procedural posture. Indeed, it is reasonable to assume that on Good Friday, judges would have already left the office and their clerks have gone home.

At some point on April 18 before midnight central time, the Fifth Circuit issued a per curiam order with a concurrence by Judge Ramirez. The unanimous panel (Ho, Wilson, Ramirez) found that the court lacked appellate jurisdiction. (I'll describe that opinion in another post.) I know the opinion came before midnight central time, because the opinion is stamped by the clerk with the date of April 18. Midnight central time is 1:00 a.m. ET. According to SCOTUSBlog, the Court's decision was released to the reporters around 1:00 a.m. ET. I can't pin down which order was issued first: the Fifth Circuit order or the Supreme Court order. It's possible the Fifth Circuit acted first. It's possible the Supreme Court acted first. There is something of a Schrodinger's Box problem. The case was both decided and it was not decided.

In the abstract, the ordering does matter. Had the Fifth Circuit issued some decision, the Supreme Court would arguably have some lower court ruling to review. This posture would avoid the Marbury problem. But if the Fifth Circuit had not yet ruled, there would be nothing for the Supreme Court to review. This temporal debate is irrelevant because the Supreme Court's order itself states that the Fifth Circuit had not yet ruled, and that was the basis for the Justices' vote. It is a curious question whether the Fifth Circuit's ruling after the Supreme Court's ruling retroactively provided some form of appellate jurisdiction nunc pro tunc. I am skeptical this could work. The general rule is that jurisdiction must be present at all times, and if jurisdiction is absent when the Court ruled, it cannot be restored after the fact. This academic question is ultimately irrelevant. At least five members of the Supreme Court issued an injunction against the executive branch without even having any lower court ruling. The Court basically granted an "Administrative Stay" of an executive action. This nomenclature is a perversion of federal court jurisdiction. If this is the Chief Justice's way of avoiding a constitutional crisis, he should promptly sign up for the benefits from A.A.R.P.

The post The Procedural Posture of A.A.R.P. v. Trump appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] SCOTUS Violates Marbury v. Madison By Granting Ex Parte Injunction Against Executive Branch In Its Original Jurisdiction

[When the Justices voted, there was no actual lower court decision to review.]

It is black letter law that the Supreme Court's original jurisdiction is fixed by the Constitution. By contrast, Congress can regulate the Supreme Court's appellate jurisdiction. As a result, a litigant cannot simply file an action in the Supreme Court to demand relief. Poor William Marbury learned this lesson the hard way more than two centuries ago.

I thought this much was clear, but apparently not. The Supreme Court's statement in A.A.R.P. v. Trump violated Marbury v. Madison. (I cannot call the statement an order or decision, because the Court was without jurisdiction.) When the Justices voted, the District Court had not issued a ruling and the Fifth Circuit ruled it had nothing to review. There was no credible allegation that the lower courts were dragging their feet. Indeed, both lower courts were moving with remarkable dispatch. Judge Ramirez's concurrence explains why there was no "effective denial of injunctive relief based on the district court's failure to issue the requested ruling within 42 minutes." As a result, there was no actual lower court decision for the Fifth Circuit to review, and no lower court decision for the Supreme Court to review. The proper order, if any, was to deny the application on the expectation that the lower courts would move promptly. The Court has done that from time to time. But I cannot recall the Supreme Court issuing a global injunction against the executive branch while the lower court was in the midst of deciding the issue.

The short per curiam order cited the All Writs Act. To be sure, courts can take actions to protect their jurisdiction. But they have to have some jurisdiction in the first place. The Supreme Court had no appellate jurisdiction. The Supreme Court can only exercise appellate jurisdiction when there is some ruling of the lower court. Here, the Supreme Court directly reviewed the government's actions. Cutter v. Wilkinson (2005) explains that SCOTUS is a "court of review, not of first view." No judge had ruled on the merits when the Supreme Court enjoined the government. This case threw Cutter to the wind. Can you imagine if the Supreme Court had bypassed all lower courts, and enjoined an emergency COVID regulation twenty-four hours after a district court TRO was filed? Worse still, the Court did not actually grant the ACLU's emergency application. This is part of a disturbing pattern of playing games with nomenclature. The Court simply issued an ex parte order against the executive branch in its original jurisdiction.

This is not the first time the Supreme Court ran afoul of Marbury on the emergency docket. Last month, in the USAID case, the Court denied the federal government's application but still issued an order to the district court to clarify which funds were enjoined. This was an advisory opinion of the worst sort: telling a lower court what to do without actually ruling on the requested relief.

What in the world is going on here? Does anyone think the Justices gave this issue more than a moment's thought in the middle of the night on Good Friday? The Supreme Court has clearly abandoned any pretense of procedural regularity at the same time they are denying the Trump Administration the presumption of substantive regularity. If Chief Justice Roberts doesn't want his rulings to be ignored, then this decision is a terrible way to proceed. Justice Barrett, a former federal courts professor, should, in the words of Justice Scalia, hide her head in a bag. There is more law in Obergefell than in this fly-by-night operation.

With a case name like A.A.R.P v. Trump, the retirement jokes write themselves!

The post SCOTUS Violates Marbury v. Madison By Granting Ex Parte Injunction Against Executive Branch In Its Original Jurisdiction appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] D.C. Circuit Stays Judge Boasberg's Criminal Contempt Proceedings

[A panel of the D.C. Circuit is encouraging Judge Boasberg to adopt a more deliberate approach.]

Late yesterday, the motions panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit issued an administrative stay delaying the criminal contempt proceedings against the Trump Administration initiated by Judge Boasberg. The stay was imposed by a majority of the panel (Judges Katsas and Rao). Judge Pillard disagreed with the decision to impose a stay. The order gives the panel more time to consider the Trump Administration's emergency order to say the proceedings.

The order reads:

Upon consideration of the emergency motion for a stay pending appeal or, in the alternative, a writ of mandamus, it is

ORDERED, on the court's own motion, that the district court's contempt-related order entered on April 16, 2025, be administratively stayed pending further order of the court. The purpose of this administrative stay is to give the court sufficient opportunity to consider the emergency motion for a stay pending appeal or a writ of mandamus and should not be construed in any way as a ruling on the merits of that motion. See D.C. Circuit Handbook of Practice and Internal Procedures 33 (2024). It is

FURTHER ORDERED that appellees file a response to the emergency motion by 5:00 p.m. on Wednesday, April 23, 2025. Any reply is due by noon on Friday, April 25, 2025.

A footnote provides:

Judge Pillard would not administratively stay the challenged order. In the absence of an appealable order or any clear and indisputable right to relief that would support mandamus, there is no ground for an administrative stay.

The post D.C. Circuit Stays Judge Boasberg's Criminal Contempt Proceedings appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Is Trump Administration Confrontation with Harvard Due to a Mistake?

[An interesting report that suggests some internal disagreement over how to handle higher education.]

Last week, the Trump Administration sent a letter to Harvard University threatening serious consequences were the University not to adopt a broad series of reforms including (but not limited to) changes in hiring and admissions. Unlike some other universities, Harvard stood its ground and announced it would not comply. Now it appears someone in the Trump Administration may have acted prematurely in sending the letter in the midst of negotiations between the two sides.

According to a New York Times report the letter may have been sent in error.

The April 11 letter from the White House's task force on antisemitism, this official told Harvard, should not have been sent and was "unauthorized," two people familiar with the matter said.

The letter was sent by the acting general counsel of the Department of Health and Human Services, Sean Keveney, according to three other people, who were briefed on the matter. Mr. Keveney is a member of the antisemitism task force.

It is unclear what prompted the letter to be sent last Friday. Its content was authentic, the three people said, but there were differing accounts inside the administration of how it had been mishandled. Some people at the White House believed it had been sent prematurely, according to the three people, who requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly about internal discussions. Others in the administration thought it had been meant to be circulated among the task force members rather than sent to Harvard.

But its timing was consequential. The letter arrived when Harvard officials believed they could still avert a confrontation with President Trump. Over the previous two weeks, Harvard and the task force had engaged in a dialogue. But the letter's demands were so extreme that Harvard concluded that a deal would ultimately be impossible.

Once the letter was sent, however, Harvard felt the need to respond to the official demands, leading to the current confrontation in which the Trump Administration is threatening to cut off all federal money to the university and to reconsider its tax-exempt status (a legally questionable move, as Eugene discusses here).

The post Is Trump Administration Confrontation with Harvard Due to a Mistake? appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers