James Maliszewski's Blog, page 24

March 31, 2025

"Now Make It YOUR Tékumel." (Part II)

I promised in my previous post on this topic to talk more explicitly about the various changes I've made to the published Tékumel setting in my ongoing-but-soon-to-end House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign. I want to do this both for the benefit of Tékumel fans, who might appreciate knowing the ways that I've made the setting my own, and for others who simply struggle with how to handle the weight of established facts and details in a pre-made RPG setting. After a decade of continuous play, many changes I've made are now so ingrained that they no longer stand out to me. However, some remain obvious, even after all this time, and it's these that I will focus on here.

I promised in my previous post on this topic to talk more explicitly about the various changes I've made to the published Tékumel setting in my ongoing-but-soon-to-end House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign. I want to do this both for the benefit of Tékumel fans, who might appreciate knowing the ways that I've made the setting my own, and for others who simply struggle with how to handle the weight of established facts and details in a pre-made RPG setting. After a decade of continuous play, many changes I've made are now so ingrained that they no longer stand out to me. However, some remain obvious, even after all this time, and it's these that I will focus on here.Science Fantasy

While Tékumel is what I have called a "secret science fiction" setting, the extent to which published materials lean into this varies. For my part, I lean into it heavily. Indeed, that's a huge part of the appeal of Tékumel: I like "fantasy" settings where all their fantastical elements are examples of Clarke's Third Law ("Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic."). This isn't really a change to "standard" Tékumel, but it colors my presentation of everything from magic (and "magic" items) to demons and the gods. This has allowed me to get a better handle on how all the setting's various parts work together and given me lots of ideas for developments in the campaign. Doing so also inadvertently gave birth to the sha-Arthan setting I've been working on for almost four years now.

MagicFor the most part, I stick to the presentation of magic and spells in Empire of the Petal Throne, which is much closer to what's found in OD&D than in later, more "authentic" Tékumel materials, like Swords & Glory. However, as I mentioned in the previous paragraph, I look on magic as "sufficiently advanced technology," even spellcasting. This means that I see a strong connection between spells and magic items, since they both harness the same forces, all of which are explicable by far future science. In this way, I've made it possible for spells to be used as energy sources to reactivate uncharged or even damaged magic items, something that's proved important on several occasions in the campaign.

Demons and the GodsIn a similar way, I views the various demon races of the Planes Beyond and even the gods themselves as highly advanced beings akin to those seen in older science fiction like Star Trek. They're "divine" or "demonic" only in an analogical sense, as humans and other more limited beings attempt to understand their nature and truly alien thought processes. I've also muddied the waters somewhat with the introduction of advanced artificial minds that are themselves effectively gods – and indeed have been mistaken as such by humans. My Tékumel is a place that's littered with science fictional elements dressed up in fantasy garb.

The Pariah GodsSpeaking of the gods, we have the Pariah Gods, a trio of deities introduced into post-EPT Tékumel as antagonistic beings more akin to Lovecraftian entities than those of the pantheon of Pavár. In published Tékumel, the Pariah Gods exist on the fringes of the setting. I've made them much more central, particularly the god known only as The One Other, who not only played a role in the imprisonment of the god Ksárul but was also a catalyst behind the founding of Tsolyánu itself. There are additional changes I've made, but I can't say much more about them here, since the House of Worms campaign is not yet over and I don't want to spoil anything for my players ...

Parallel Worlds, Time Travel, and the CollegeFurthering my science fictional emphasis, I've made much use of parallel versions of Tékumel, time travel (or at least asynchronous temporality), and the Undying Wizards of the College of the End of Time. None of these things is central to my version of Tékumel but they have roles to play. For example, Toneshkéthu, a student at the College, has been a longstanding ally of the characters. Because she exists in the far future of Tékumel, she often appears "out of sequence" from their perspective, remembering things that haven't yet happened and being unaware of events in which she (or a version of her) actually participated.

HistorySpeaking of the passage of time, the societies of Tékumel as presented in published materials are old – unbelievably so in my opinion. There is recorded history stretching back more than 10,000 years and I simply can't believe that. Consequently, my version of Tékumel is old but not that old, with suggestions to the contrary simply being rhetorical/poetic exaggerations for effect.

TsolyánuThe titular Empire of the Petal Throne is presented as if it's much more stable and monolithic than I can accept. Consequently, I've presented Tsolyánu and much more varied and prone to periods of rebellion and even anarchy. Customs and traditions vary from city to city and region to region, even to the point where Tsolyáni from one part of the Empire feel almost like foreigners in another.

Salarvyá and Yán KórI've made some changes to two of Tsolyánu's neighboring empires. In the case of Salarvyá, I made it an elective monarchy that periodically convulses with chaos as the time to elect a new king draws near rather than a kingdom ruled by the same dynasty for untold thousands of years. Likewise, Yán Kór is presented in published materials as a major rival of Tsolyánu, thanks to the determination of its leader, Baron Ald. I've opted instead to make it a weak confederation of city-states that's more a threat to itself than to anyone else. Consequently, the war with Yán Kór that occurred in "prime" Tékumel never did in mine.

Heirs to the Petal ThroneI included all the heirs mentioned in the original Empire of the Petal Throne, but almost none of those introduced in later materials. In particular, I dispensed with Mirusíya, whose revelation and subsequent elevation to the Petal Throne in official Tékumel never sat well with me for a number of reasons. Instead, I introduced my own additional heirs, as well as my own spin on the existing heirs.

As you can see, my personal Tékumel doesn't deviate too much from what's found in published materials. It's more a matter of emphasis, which allows me to put my own spin on certain aspects of it. This, in turn, allows me to shape it a setting conducive to the kind of adventures and situations that play to my own interests and strengths as a referee. I think it's worked very well over the course of the ten years we've been playing House of Worms. That said, I will be glad when the campaign is done at last. I've inhabited Tékumel for a long time now and am looking forward to he opportunity to explore a new setting with my players.

A Maker's Enigma

Among the more frequently unearthed relics of the Vaults are finely wrought containers of metal and ceramic, known as Maker’s enigmas or, in some circles, cipher caskets. Each is a marvel of ancient craftsmanship, its intricate locking mechanisms guarding the secrets within from all but those who possess the proper key. Yet even such defenses are not impervious; the Chenot, with their deft tendrils, have a knack for unraveling these age-old puzzles. Some enigmas conceal deadly traps, though such precautions are seldom found in the smaller ones, like the example shown here. The treasures within are as varied as they are coveted: coins and gems, alchemical pastilles of restoration, rolled sheets of ushua-paper inscribed with the cryptic Hejeksayaka script, or even arcane devices of unknown purpose. An unopened Maker’s enigma, especially one of larger size, commands a fortune in the great cities of da-Imer and Eshkom, where eager buyers wager immense sums on the hope of unveiling a priceless relic of the Makers.

Art by Zhu Bajiee

Art by Zhu Bajiee

March 30, 2025

Musings on Poll Results (Part III)

I'm going to take a break from these weekly polls. While I have found them useful in getting a better sense of Grognardia's readership demographics, I've found the poll service I've been using somewhat limited in its capabilities. Many of the questions I'd like to ask would require a much more sophisticated set-up and I don't, at present, have access to that. I'll spend the next few weeks researching the matter to see if I can come up with a polling system more suited to what I desire. If you should have any suggestions or recommendations in this regard, I'd be grateful if you make them known to me in the comments.

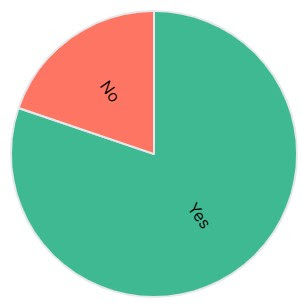

The poll, "Was Your First Tabletop RPG Dungeons & Dragons?," yielded the results I more or less expected:

Since its first appearance in 1974, D&D has been the proverbial 800-lb. gorilla of the roleplaying hobby. That remains true even today, despite – or perhaps because of – the proliferation of RPGs. As you can see, the vast majority of my readers started with D&D, as I did too. It's pretty uncommon to meet someone who entered the hobby through another game, though I currently play with at least one person who did so.

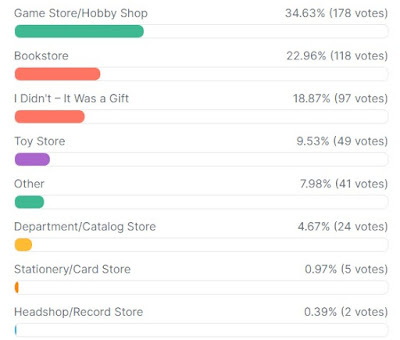

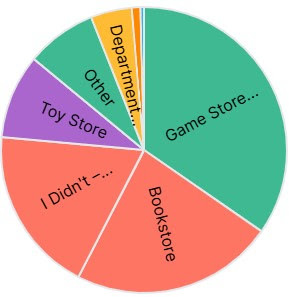

The poll, "Where Did You Buy Your First Tabletop RPG?," was a bit of a mess, if I'm honest. It was this poll that made it clear to me I needed a better means of collecting data. Even leaving aside the inadequacies of the poll itself – how did I not include "comic shop" as an option? – there are still some interesting results here.

Taken together, "game store/hobby shop" and "bookstore" accounted for nearly 60% of the responses. That's not really a surprise, since those are, in my opinion, the two most obvious places to purchase RPG. More interesting is the third most popular response: "I Didn't – It Was a Gift." Just shy of 20% of all respondents choose this option, which suggests that a significant number of people owe their involvement in the hobby to someone else. This is a case where I wish I could more easily follow up certain answers. I'd love, for example, to know who gave these gifts and also whether or not the gift was requested or an unexpected surprise – hence why I'm going to be looking for alternatives to Strawpoll in the coming days.

Taken together, "game store/hobby shop" and "bookstore" accounted for nearly 60% of the responses. That's not really a surprise, since those are, in my opinion, the two most obvious places to purchase RPG. More interesting is the third most popular response: "I Didn't – It Was a Gift." Just shy of 20% of all respondents choose this option, which suggests that a significant number of people owe their involvement in the hobby to someone else. This is a case where I wish I could more easily follow up certain answers. I'd love, for example, to know who gave these gifts and also whether or not the gift was requested or an unexpected surprise – hence why I'm going to be looking for alternatives to Strawpoll in the coming days.

March 29, 2025

"Now Make It YOUR Tékumel." (Part I)

Last week, in the comments to last week's post, "Rules, Rules, and More Rules," reader Bonnacon asked me to elaborate on something I wrote there. Specifically, he wanted to know more about this:

However, I still kept the magic-user and priest classes as separate things with unique skills for each, along with lots of other stuff that doesn't quite "fit" into the setting as it evolved. My vision of Tékumel is my own and undoubtedly at odds with the "official" version in several places.

This is all in reference to my ongoing – and soon to end – decade-long House of Worms Empire of the Petal Throne campaign. When I began the campaign in March 2015, my intention was to stick with the original 1975 EPT rules as closely as possible. That was, in fact, part of the reason I started the campaign in the first place: to play in Tékumel using its original ruleset. Those rules are quite "primitive" by contemporary standards, being an offshoot of 1974 OD&D. For the most part, I'm quite fine with this, since I prefer minimal (even minimalist) rules over more complex ones.

Of course, in extended periods of play, especially over the course of ten years, it's all but inevitable that even minimalist rules will start to change in response to unexpected circumstances. That's certainly the case with the House of Worms campaign, where we've made little adjustments here and there. For example, I've allowed the optional adventurer character class from issue #31 of Dragon (and further developed by Victor Raymond). Similarly, I clarified the way that weapon skills work in the game, since the rules don't really explain what purpose they serve or what penalties a character might suffer if he doesn't possess the skill associated with a weapon he's currently wielding.

The matter is further complicated by the fact that Empire of the Petal Throne presents an early version of Tékumel, the earliest published. Although most of its setting is present in the 1975 rulebook, much of it is still vague. For example, clans are barely mentioned at all, despite later being a foundational aspect of Tsolyáni society. Now, since I was a long-time Tékumel fan playing in the 21st century, I was already familiar with many elements later added to the setting. Even though my goal with the House of Worms campaign was to go back to the beginning, so to speak, it was nigh impossible for me not include things like clans, even though EPT doesn't really include them.

Furthermore, even in later Tékumel materials, such as the encyclopedic Tékumel Source Book released in 1983, there are still matters that are not fully explained or even discussed. Any attempt to referee a campaign for more than a short period of time will certainly run into "blank spots" that needed filling. That's especially true of the deeper mysteries of Tékumel – prehistory, the gods, parallel worlds, the College at the End of Time, and so forth – but it's just as true of even more mundane topics, like the lands at the edges of the continental map.

It has sadly been my experience that a lot of Tékumel fans have been reluctant to come up with their own answers, instead rushing to the Source Book or archived Usenet posts from the 1990s for the Truth™. I think that's a mistake for many reasons, not least because the introduction to the Source Book itself ends with the following:

Even if we were to issue a monthly newsletter or exchange data by telephone, there is no real way to prevent your history from diverging from mine. I can indeed provide further materials – and some are already available from the publisher of this book – but we cannot keep your Tékumel from drifting away from mine. This is as it should be. You have just bought MY Tékumel. Now make it YOUR Tékumel.

I think this is good advice for a referee making use of any published setting, but it's especially so for Tékumel, whose idiosyncrasies are many. Trying to get every detail right and never deviating from every jot and tittle of its diffuse canon would be a Herculean task and, ultimately, a Quixotic one. That's why I decided early in the House of Worms campaign not to get too hung up on such matters. My goal was a fun roleplaying experience for everyone involved and achieving that often meant adding, subtracting, and otherwise altering previously established material about Tékumel.

I'll get into more specifics in Part II of this post next week. With luck, it won't be too "inside baseball" in its content and readers without much knowledge of Tékumel will also find it useful.

March 27, 2025

Campaign Updates: Black Box

Barrett's Raiders

This week saw the characters finally cross the Atlantic (with a brief stop at Lajes in the Azores for refueling), arriving at "Naval Station Norfolk" on 3 December 2000. I used scare quotes, because their destination was located not at Norfolk proper – which took a 1 MT nuke in November 1997 – but rather at Newport News on the other side of the James River. Though the US Military Emergency Administration (USMEA, the acronym used by the military government) had made efforts to rebuild portions of the original station, it was still too irradiated for long-term human habitation, hence the relocation. Plus, both Langley AFB and Fort Eustis were nearby, as well as the National Defense Reserve Fleet ("Ghost Fleet") of inactive naval vessels.

Once in Virginia, the members of Barrett's Raiders were processed and given barracks prior to being interviewed, as per the directives of Operation Resolute. Because of they'd impressed General Hawthorne in West Germany, he asked USMEA Command to make every effort to keep the characters together as a single unit. They clearly possessed unique skills that could serve USMEA well in the anarchy of post-war America. For that reason, they were interviewed together by Captain Daniel Callahan, whom the characters immediately suspected of being their "handler" (or commissar, as former Soviet doctor Vadim later called him). He filled them in on the current situation in Virginia, as well as recent efforts by USMEA to deal with local threats.Callahan explained that his superiors wanted to keep Barrett's Raiders together as "Military Liaison Group 7," operating with a high degree of autonomy as force multipliers for local groups in the Delaware/Maryland/Virginia (Delmarva) region who are attempting to rebuild. If they were amenable to this arrangement, he tasked them with traveling to Fort Meade, Maryland, where a former official of the pre-war government had established a safe area and was looking for assistance. Though nominally aligned with the "unrecognized civilian authority" in Omaha, the official needed all the help he could get. Callahan explained that, if the characters can assist him, it'd go a long way toward helping to bridge the gap between USMEA and their rivals. After brief discussion, the characters agreed, thereby accepting continued service with the US Army.

Dolmenwood

Having reached the Shadholme Lodge and the camp that grew up around it in anticipation of the Hlerribuck festival, the characters spent much time settling in. They soon discovered that the Hlerribuck had attracted people from across Dolmenwood, including people whom they knew. Sir Clement encountered Sidley Fraggleton, a childhood friend, who was engaged to another friend, Celenia Candleswick. Celenia's father, Sir Jappser, didn't think much of Sidley (or Clement for that matter), which is why Sidley was glad to hide from him in the company of Clement and his comrades. For their part, the rest of the characters mostly ignored Sidley as they went about their own business.

Part of that business involved Falin being impressed into service as the temporary vicar of the memorial chapel set up on the grounds of the Lodge. Apparently, the priest who was expected to be here, Father Dobey, was nowhere to be found and many of those who'd traveled to the festival required the services of a cleric. Falin reluctantly agreed to this and set herself up in the chapel – which Sidley promptly claimed as his "sanctuary" from Sir Jappser and his brutish friend, Shank Weavilman – and began tending to a number of odd folk who happened by.While in the chapel, Alvie found a dusty key on the floor. This led him and Marid to begin looking around the place, assuming that the key must be for a lock in the church itself. After a while, they discovered a keyhole at the base of the chapel's altar. When used, the key unlocked the altar itself, which could be slid to one side, revealing a dark shaft into the earth, complete with a set of rungs leading downwards. Locking the chapel doors, Alvie descended some 20 feet down before discovering a door, on the other side of which he heard Breggle voices. He climbed back up and reported what he saw and heard. The characters decided this was worthy of investigation, but it would have to wait until nightfall, lest they draw too much attention to their activities.

House of Worms

The day of Kirktá's presentation to the city of Béy Sü and, by extension, the entire Empire of Tsolyánu, as a declared heir of the now-deceased Emperor Hirkáne was finally upon the characters. The festivities began early, with food and entertainment in the courtyards of the Golden Bough clanhouse. This was intended for members of the lower clans, while the high clans would partake of refreshments inside. It was inside that Kirktá, attired in the garb of an imperial prince, would receive his visitors, well-wishers, and rivals. The characters had made an effort to advertise the party widely and had specifically invited other known heirs to come and meet their newly revealed (half-)brother.

Prince Eselné sent his regrets, saying that he was "needed elsewhere." Prince Dhich'uné said the same, but promised to send someone in his place, with "a suitable gift." The gift was a large black box, borne by four slaves, and presented by Jayárgo hiKhánmu, a priest of Sárku of long association with Dhich'uné. Jayárgo was polite and respectful and explained that the box contained "something most precious" and would aid Kirktá in achieving his destiny. Naturally, this frightened Kirktá, who felt that, whatever it contained, it might serve as a catalyst for breaking down the mind-bar placed on his memories years ago. Rather than risk that, he had the box sent away to a safe place and planned to view its contents later.

Throughout the evening, Kirktá met several other people of significance, most notably Princess Ma'ín, who arrived with great fanfare. Her arrival attracted a lot of attention away from Kirktá, for which he was somewhat grateful. Ma'ín's chat with Kirktá was laden with subtle – and not so subtle – innuendo about his future. By comparison, Prince Táksuru was straightforward in his interactions, urging Kirktá to stay out of "the game" and promising him and his companions rewards if he did so. Prince Rereshqála, meanwhile, explained that he had hoped to avoid entering the Choosing of the Emperors himself, but that he would gladly do so if it meant ensuring Dhich'uné did not become emperor. He further suggested that all the other heirs might need to work together toward this one end. He then departed and said they would speak again soon.March 25, 2025

The Articles of Dragon: "Even Orcish is Logical"

I've been fascinated with languages and alphabets since I was a young child. Consequently, when I discovered roleplaying games in late 1979, it didn't take me long to start including snatches of made-up languages and scripts into my games. By the time I'd created my Emaindor campaign in high school, I was ready to try my hand at a full-on constructed language – which I, in fact, did, complete with a script imagined for me by a friend of mine in college. That language, Emânic, wasn't very good, as conlangs go, but I was nevertheless pleased with myself and used it primarily for place names in certain regions of the setting.

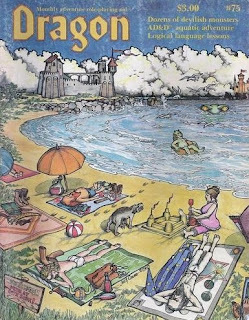

I've been fascinated with languages and alphabets since I was a young child. Consequently, when I discovered roleplaying games in late 1979, it didn't take me long to start including snatches of made-up languages and scripts into my games. By the time I'd created my Emaindor campaign in high school, I was ready to try my hand at a full-on constructed language – which I, in fact, did, complete with a script imagined for me by a friend of mine in college. That language, Emânic, wasn't very good, as conlangs go, but I was nevertheless pleased with myself and used it primarily for place names in certain regions of the setting.A major catalyst in my decision to do this were articles in Dragon, especially the pair that appeared in issue #75 (July 1983), the first of which I'll discuss in this post. Entitled "Even Orcish is Logical" and written by Clyde Heaton (who'd previously written another inspirational language article), it offered excellent practical and theoretical device to the novice constructor of fantasy languages. That's important and big reason why the articles in this issue had such an impact on me: they were more than high-minded musings about language; they provided lots of advice and examples on how to make your own languages.

In the case of "Even Orcish is Logical," Heaton spent a lot of time talking about the "feel" of a language, from its sounds to its grammatical constructions to its vocabulary. His thoughts would probably not pass muster with actual linguists, but that was beside the point. Heaton was providing useful guidance to referees who wanted to make languages that are suitable for use in RPG campaigns rather than ones that could withstand the scrutiny of professional academics. So, for example, Heaton notes that the Orcish language, which he uses as is his example, has "mostly harsh, guttural sounds." While he attempts to ground this in something "real" – the protruding fangs and tusks of the Orcish mouth – that's not his main concern. Rather, it's that the Orcish language sounds "right" for the language of savage humanoid enemies in Dungeons & Dragons.

Heaton opts for a similar approach when looking at the grammar of Orcish. Orcs are not a refined people, so the grammar of their language is simple and direct. Again, this approach wouldn't stand up to careful study by a scholar of languages, but it works well enough for fantasy RPGs. At least, that's the lesson I took from it: establish a frame or lens through which to imagine the language you're planning to create and then make decisions about its sounds, grammar, and vocabulary that fit that frame or lens. Unless you're very dedicated and want to follow in the footsteps of Tolkien, this is a reasonable way to proceed, I think. Heaton also points out that there's no need to create an extensive vocabulary for game purposes, since even real languages use only a very small number of words for everyday communication. The number needed in a RPG are probably even smaller. This is important to point out, particularly to readers like my youthful self, who might otherwise have spent weeks or months coming up with words for all sorts of things I'd never need for my campaign.

"Even Orcish is Logical" is a terrific article, one of my favorites from the period when I was reading Dragon regularly. When paired with the other language article from the same issue (about which I'll write next week), it played a significant role in my development as a referee and roleplayer more generally. Re-reading it filled me with a lot of memories and good feelings from that summer just before I started high school. It was a frightening but heady time for me, as I made a transition from one stage of my life to another. Having RPGs and magazines like Dragon available to me made it much less scary than it otherwise might have been and, for that, I'll always be grateful.

March 24, 2025

Where Did You Buy Your First Tabletop RPG?

For this week's poll, let me offer a few clarifications. First and most importantly, I'm asking this question about the very first tabletop RPG you bought for yourself and owned, not played. In some cases, these may be different. I want to know about the very roleplaying game for which you had a personal copy. Second, if you didn't buy your first RPG yourself but were given it as a gift, there is an option for that in the poll. Please use it, because I am curious to know how common it was to give roleplaying games as gifts.

For the five main options, I chose places of business that I can recall selling RPGs during my youth. I have undoubtedly neglected to include some possibilities. If you bought your first tabletop roleplaying game somewhere I didn't specifically mention, please choose "Other" and explain your answer in the comments. I'd love to know about some of the more unusual places where RPGs have been sold over the years.

Loading...

March 20, 2025

Rules, Rules, and More Rules

I'm currently refereeing three different campaigns at the moment: House of Worms, using Empire of the Petal Throne; Barrett's Raiders, using the Free League edition of Twilight: 2000; and Dolmenwood, using the rules of the same name. Of the three, only two – EPT and Dolmenwood – can be called "old school" in the usual sense of the term, though T2K has a lot in common with many old school games, specifically its focus on hexcrawling and resource management. That said, I wouldn't really call Twilight: 2000 "old school" without some big caveats. That's no knock against it, since my players and I have been enjoying ourselves with it for more than three years now, but I think it's important to note these things, particularly in light of the topic of this post.

Empire of the Petal Throne is a very early RPG. Released in 1975, it's a close cousin to OD&D in terms of rules, meaning that it's not very mechanically complex. Dolmenwood is a little bit heftier, being largely derived from Moldvay/Cook Dungeons & Dragons (1981), itself a clarification and expansion of OD&D. Twilight: 2000 (2021) uses a variation of Free League's "Year Zero" rules, versions of which can be found in most of the company's games, like Forbidden Lands or Vaesen. The T2K variant is a bit more complex than the others, owing to its inclusion of modern firearms and vehicles.

In each campaign, I rarely use the game's rules as written. I don't mean that I've introduced lots of house rules (though I have in a few cases). I mean that I often ignore the rules. When playing, I often don't want to slow down the flow of the session by having to refer to a rulebook or a chart. Instead, I prefer to rely on my memory and that of the players, which means that we're more likely to strictly apply those that we remember than those we don't. I call these kinds of rules "sticky" rules, because they stick in your memory.

One of the reasons I prefer old school RPGs like D&D is that I find their rules much stickier than those of newer games. To some extent, that's simply a function of familiarity. I've been playing D&D and Traveller for more than four decades; I know them almost like the back of my hand. I lack this familiarity with games I learned more recently. On the other hand, there's no question that most older roleplaying games are much more mechanically simple than those that came later. Again, this is a generalization and there are plenty of counterexamples. My point is that, as both a referee and a player, I'm much more comfortable with fewer and simpler rules, since I'm much more likely to remember and, therefore, use them.

But, as I already noted, even in games like EPT or Dolmenwood, I regularly handwave or outright ignore rules in the heat of play. For example, Empire of the Petal Throne includes spell failure rules. Depending on a character's level, psychic ability, and the type of spell, there's a chance a spell might not function. At mid to higher levels, this chance is minute, but there's still a chance of failure. Despite this, I don't always make the players roll, since there are many occasions when I feel it unnecessary or disruptive to the flow of the action. I defer to my own judgment here rather than the rules and the players have never complained. Were they to do so, I wouldn't hesitate to use the rules as written, but I like to think that, after a decade of play, we've built up enough trust that that no players worries much about how I'd adjudicate in-game situations.

I think about this question a lot, because many aspects of the new Twilight: 2000 rules, chiefly the combat system, are more complex than I like. There's nothing wrong with them and, by many measures, they're much simpler than the original GDW T2K combat rules. However, I'm not fond of them and I frequently dispense with many persnickety aspects of them in the interests of speed and simplicity. Again, the players rare complain about this and accept my judgments. Had I the ability to start this campaign over again, I might have opted for simpler, more straightforward rules, but, after more than three years, it's too late for that, so we muddle through.

That's more or less where I am with rules these days: when give the option, I prefer simple, even simplistic, rules over more elaborate and complex ones. I'm not opposed to trying to model complicated situations and activities mechanically and, under the right circumstances, could even find that enjoyable. However, as a referee running a weekly game over the course of many years, I have come to find that rules I can't keep in my head without recourse to a book or a chart or a table don't hold a lot of appeal for me anymore. Consequently, my latest drafts of the rules for Secrets of sha-Arthan are decidedly much simpler than earlier ones. It's yet another way that my experiences as a referee have colored my own design work – and for the better, I hope.

March 19, 2025

Hope Among the Ruins

Owing to scheduling conflicts, my Barrett's Raiders Twilight: 2000 campaign didn't meet this week. While we've striven to meet every week over the course of the three years and three months we've been playing, such hiccups aren't uncommon. Still, I can't deny I was a little bit disappointed, because this week would have been the first session in the campaign to take place on American shores. After three years of war on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, the characters are finally home.

Owing to scheduling conflicts, my Barrett's Raiders Twilight: 2000 campaign didn't meet this week. While we've striven to meet every week over the course of the three years and three months we've been playing, such hiccups aren't uncommon. Still, I can't deny I was a little bit disappointed, because this week would have been the first session in the campaign to take place on American shores. After three years of war on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, the characters are finally home.

The reason I was disappointed is that playing Twilight: 2000 in post-war America is something I've wanted to do since the late 1980s. In a very real sense, bringing Barrett's Raiders to this point is the culmination of a nearly forty(!) year-old dream of mine. Back when I originally played T2K, I only owned the first four adventure modules – The Free City of Krakow, Pirates of the Vistula, The Ruins of Warsaw, and The Black Madonna. These are all set in Poland, so my campaigns stayed in Eastern Europe rather than venturing elsewhere.

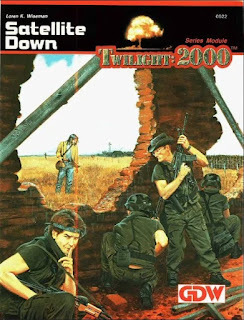

Clearly, though, GDW had a great interest in seeing Twilight: 2000 characters return to the USA. After 1986's Going Home, the company produced nine modules set in America. With the exception of the first, Red Star, Lone Star, which dealt with a Soviet-backed Mexican invasion of Texas – think Red Dawn but a little more grounded – the modules were all notable for their focus on rebuilding the country after the nuclear strikes of 1997 and the chaos that followed.

Clearly, though, GDW had a great interest in seeing Twilight: 2000 characters return to the USA. After 1986's Going Home, the company produced nine modules set in America. With the exception of the first, Red Star, Lone Star, which dealt with a Soviet-backed Mexican invasion of Texas – think Red Dawn but a little more grounded – the modules were all notable for their focus on rebuilding the country after the nuclear strikes of 1997 and the chaos that followed. Granted, the modules still offered plenty of opportunities for violent mayhem, but it was generally directed toward opportunistic warlords and authoritarian New America cells, forces that need to be swept away before any kind of rebuilding might be possible. And while MilGov and CivGov are most definitely at odds with one another, neither side is demonized or reduced to a caricature. It's a messy situation that creates lots of scope for interesting situations and scenarios.

And that's what most excites me about Barrett's Raiders finally making the transition to the Not-So-United States of America. As American soldiers brought home from Europe by the US Military Emergency Administration, the characters are put in a difficult situation: continue to obey the Joint Chiefs despite their extra-constitutional assumption of authority or put themselves at odds with their former comrades in arms. It's a situation made all the more complicated by the equally dodgy authority of President Broward and the reconstituted Congress – to say nothing of the threat of New America and others taking advantage of the breakdown in civil society.

Twilight: 2000 got a reputation in some circles as an immoral power fantasy RPG that made light of the deaths of millions in nuclear war. I think only the most superficial reading of either the game or (especially) its adventure modules could support such a false conclusion. This is most definitely not a game about reveling in the collapse of civilization but rather one where the characters can actively participate in helping to reconstruct that civilization. As campaign frames go, that's a truly worthy one in my opinion, one I've wanted to explore with some friends for decades. Now that I'm finally getting the chance to do so, my enthusiasm is high. Expect increased posting about Twilight: 2000 and the events of the Barrett's Raiders campaign.

Twilight: 2000 got a reputation in some circles as an immoral power fantasy RPG that made light of the deaths of millions in nuclear war. I think only the most superficial reading of either the game or (especially) its adventure modules could support such a false conclusion. This is most definitely not a game about reveling in the collapse of civilization but rather one where the characters can actively participate in helping to reconstruct that civilization. As campaign frames go, that's a truly worthy one in my opinion, one I've wanted to explore with some friends for decades. Now that I'm finally getting the chance to do so, my enthusiasm is high. Expect increased posting about Twilight: 2000 and the events of the Barrett's Raiders campaign.

March 18, 2025

Retrospective: The Complete Book of Elves

By the early 1990s, AD&D 2nd Edition was in full swing, and one of its defining features was the proliferation of entries in the Player's Handbook Rules Supplement (PHBR) series, commonly called the Complete books. These were player-focused supplements initially aimed at expanding the options for various classes that were eventually expanded to other topics, including races. The series is mixed bag, with most volumes following in the footsteps of The Complete Fighter’s Handbook – solid and unremarkable. However, a few stand out for how bad they were, The Complete Book of Elves, published in 1993, being my candidate for the worst (feel free to nominate your own in the comments).

Written by Colin McComb, The Complete Book of Elves is, at its core, an expansion of the already-powerful elf race in AD&D. But whereas earlier material presented elves as skilled but balanced adventurers with unique strengths and weaknesses, this book instead leans hard into the idea that elves are just better –smarter, faster, more artistic, more magical, more attuned to nature, and, of course, longer-lived – than virtually every other playable race in the game.

This emphasis is the start of where the book runs into trouble. It doesn’t just provide players with more options for elven characters; it actively reinforces an attitude of elven superiority, sometimes to an absurd degree. Take, for example, this passage:

No elf will ever simply perform a function when he can do it with flair and style. If a human forges a sword, he creates a piece of metal that cuts and slashes. If an elf forges a sword, he creates a masterpiece of balance, beauty, and power.

That's more or less the tone of the entire book. Elves are naturally superior to humans and other races in virtually every way that matters. Their weapons are better, their magic is more refined, their civilization more enlightened, their senses sharper, their emotions deeper. Even their music is better!

If it were merely a matter of tone, The Complete Book of Elves would simply be remembered as insufferable. However, the book follows suit with its rules expansions as well and this, in my opinion, is where it reaches a new level of egregiousness. The new elven kits, which are supposed to offer distinct roleplaying options, tend to be overloaded with benefits and underweighted on drawbacks. The bladesinger, for instance, is a combat-ready spellcaster with virtually no downside beyond its limitation to one weapon. The wilderness runner is an elf so in tune with nature that he can literally run faster than a horse. Even some of the purported elven disadvantages, like the elves' reluctance to use heavy armor, are framed as virtues rather than limitations.

It’s not as if the book is poorly written. McComb has a decent grasp of language and some of the information he presents, particularly concerning elven philosophy and their approach to magic, is interesting. However, it is so unbalanced in its portrayal of elves that it feels almost like a work of in-game propaganda rather than a neutral sourcebook. I don't think that was McComb's intention, but, even if it were, I think he went a bit overboard in his approach. I distinctly recall that, during the '90s, The Complete Book of Elves was the butt of frequent jokes by all but the most dedicated elf fanboys. In my local group, we referred to it as "The Complete Book of Gods," because of its overpowered kits and supercilious prose.

Despite this, The Complete Book of Elves still holds some interest today, if only from a historical perspective. It's an artifact of a time when AD&D was leaning much more heavily into the "story" or "narrative" approach that was pioneered almost a decade earlier in Dragonlance. The book has less concern for mechanical balance than it does for presenting a nonhuman race in sufficient detail for maximum player immersion. I don't think that's necessarily a bad thing – I'm a longtime fan of Roger E. Moore's "Point of View" series in Dragon, for example – but I can't help but feel as the racial Complete books, especially this one, go too far in this direction.

Ultimately, I think The Complete Book of Elves serves as an object lesson in the dangers of overindulging a single race or concept in a game. I prefer it when a supplement expands options, not elevates one choice as obviously better than all the others. Based on my undoubtedly biased experience, this book simply exacerbated an existing problem: players already drawn to elves didn’t need more reasons to see them as superior. It's a flawed and indulgent book, worth a read only if you want a window into some of the worst tendencies of TSR and AD&D during the early to mid-1990s.James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers