James Maliszewski's Blog, page 22

April 14, 2025

"Experience the Life of a Secret Agent ..."

Though I played a fair bit of Top Secret in my youth, I think my favorite espionage RPG was James Bond 007 from Victory Games. Even ignoring its connection to Ian Fleming's novels and the United Artists film series, James Bond 007 was in my opinion a great bit of game design, with elegant, emulative rules and terrific graphic design. I had a ton of fun with it during the brief time when it was in production (1983–1987).

April 13, 2025

Initial Thoughts on Dragonbane

As I mentioned at the start of the month, my ongoing Dolmenwood campaign is on a short hiatus while one of the players is away traveling. In the meantime, another member of the group has kindly offered to run a few sessions of Dragonbane, Free League's fantasy roleplaying game, and I’ve taken the opportunity to step out from behind the screen and join as a player. I jumped at the chance, not only because Dragonbane has been on my radar for a while, and this seemed like the perfect time to give it a try.

For those unfamiliar with it, Dragonbane is the modern English-language evolution of Drakar och Demoner, Sweden’s first major fantasy RPG, originally released in 1982. That game was built on Chaosium’s Basic Role Playing (BRP) system, adapted under license and inspired in part by Magic World and RuneQuest. Over the decades, Drakar och Demoner went through numerous editions in Sweden, each refining or reshaping its rules. In 2023, Free League acquired the rights and reimagined the game as Dragonbane, distilling its BRP roots into something faster, lighter, and more accessible. While it retains the BRP hallmarks, like skill-based resolution, opposed rolls, it swaps out percentile dice for d20s and favors simplicity wherever it can.

While I’ve played my fair share of BRP-based games over the years, most of my fantasy RPG experience comes from Dungeons & Dragons and that likely shapes how I see other systems in the genre. That said, Dragonbane feels immediately familiar in all the best ways. Like older editions of D&D, character creation is fast and to the point: you choose a kin (i.e., race), a profession (class), some skills, and you’re good to go. It's more straightforward than making a character in RuneQuest and only marginally more involved than in D&D. You can feel the BRP ancestry throughout, but almost everywhere the system has been pared back to emphasize ease of play. The use of d20s streamlines resolution, and Dragonbane replaces modifiers with “boons and banes,” a system akin to advantage and disadvantage.

All of this is well and good, but what pleasantly surprised me was the combat system. I’m someone who often finds combat a necessary but uninspiring part of roleplaying games. I don’t dislike it outright, but I rarely look forward to it. In Dragonbane, though, combat has consistently been fun: brisk, dynamic, and full of opportunities for clever play. In fact, I’ve found myself anticipating combat encounters, which is not something I say lightly. It’s almost as if the Dice Gods are mocking me for having just written a post about my ambivalence toward combat mechanics. If so, I don’t mind. I’m grateful to have found a system that’s helping me understand what I do enjoy in RPG combat.

Each round, a Dragonbane can move and act. Special weapons or abilities can bend the rules in flavorful ways, but the core loop remains fast and approachable. Initiative is determined with cards rather than dice and reshuffles every round, introducing a layer of unpredictability. There are ways to act out of turn or swap initiative order, which adds some tactical flexibility. Beyond that, there are other mechanical wrinkles, such as morale checks, weapon breakage, special maneuvers, that bring the system to life without bogging it down.

That, for me, is what stands out about the Dragonbane combat system: it hits a sweet spot that’s hard to find. Too often, combat systems fall into one of two traps: they’re either so streamlined that they feel flat or they’re so loaded with options and subsystems that the pace suffers. Dragonbane threads the needle rather well in my opinion, offering just enough crunch to make combat engaging, but not so much that it becomes a slog. Whether this will remain my considered opinion over the long haul remains to be seen, but so far, it’s been a delight.

April 11, 2025

Field Assessment

FIELD ASSESSMENT – SUBJECT: “NEW AMERICA” MOVEMENT

CLASSIFICATION: TOP SECRET – EYES ONLY

DATE: 04 DECEMBER 2000

COMPILED BY: DIA FIELD SECTION 47B, MILGOV REGION 3

REFERENCE NO.: 00-FS47B-NA/337-A

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY:

New America (NA) is a revolutionary, ultra-populist insurgent movement that has emerged as one of the most ideologically coherent and operationally dangerous factions within the constellation of Free States groups. Drawing on a hybrid ideology of anti-elitism, apocalyptic renewal, and militarized spirituality, NA frames itself not merely as a resistance group but as the vanguard of a new American order, one that seeks to erase the legacy of both pre-war democracy and Cold War ideological systems.

Recent intercepts and recovered propaganda confirm the movement’s alignment under a codified manifesto titled "What We Believe." This document outlines a doctrine combining post-constitutional rejectionism, anti-globalist conspiracy theory, revolutionary spiritualism, and a violent commitment to social purification. The movement’s symbolic and organizational cohesion appears increasingly centered around a messianic figure known only as “The Preacher.”

IDEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT:NA’s core beliefs represent a radical break from traditional American political culture, including both constitutional republicanism and Cold War binary thinking. Their worldview can be summarized as a total rejection of past institutions and a call for violent national rebirth.

Key Ideological Tenets:1. The Old Order is Dead

The U.S. Constitution is viewed as null and void.All prior political authority (civilian or military) is illegitimate.USMEA and its predecessor institutions are framed as inheritors of tyranny.2. No Left, No Right, Only Revolution

The movement rejects traditional political alignments, calling them “engineered divisions.”Promotes a unifying mythology of betrayal by elites, which includes politicians, global corporations, media, and international institutions.3. Might and Purity Over Law

Embraces social Darwinism: strength, conviction, and “righteousness” justify authority.Denounces attempts at restoration or reconciliation as weakness and collaboration.Espouses purgative violence against those who cling to “the broken world.”4. Anti-Systemic Economic Doctrine

Rejects both capitalism and communism as oppressive foreign ideologies.Endorses an undefined system where land, labor, and leadership are “earned through struggle.”Preliminary assessments describe this as a proto-feudal or militarized collectivist model.5. War as National Sacrament

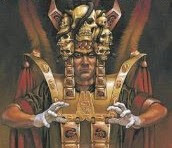

Conflict is seen as a necessary and purifying process.Peace is treated as dangerous, degenerative, and indicative of weakness.The movement frames its own violence not as criminal or insurgent, but as sacred duty.6. The Preacher

A charismatic cult figure central to movement cohesion.Portrayed as a prophetic survivor of the war, bearing mystical insight.Internal communications suggest his authority is absolute and not subject to debate.Believed to function as both ideological architect and operational commander.ORGANIZATION AND STRUCTURE:NA is not a monolith but shows a high degree of internal discipline and shared doctrine across cells. Recent captures suggest a federated structure under the overarching authority of the Preacher’s inner circle, known as “The Assembly.” Recruitment appears strongest among disenfranchised rural populations, former National Guard units, and survivors embittered by USMEA operations or inaction.

Key features:Standardized iconography (e.g., red, white, and black flag; stylized eagle with broken chains).Indoctrination-focused training camps.Control over several small to medium-sized settlements in the Appalachian region and the Midwest.Covert infiltration of supply lines and local administrations in contested zones.CAPABILITIES AND ASSETS:While not possessing conventional force parity, NA continues to exhibit high operational agility and a growing capacity for both sabotage and strategic occupation.

Military Estimate:10,000–14,000 armed personnel in rotating field units.Heavily reliant on captured or scavenged military materiel.Capable of deploying small, well-coordinated strike teams.Intelligence indicates internal vetting for ideological loyalty and doctrinal purity.Weapons of Concern:Persistent reports (unverified) of VX nerve agent in NA-controlled areas.Weaponization capability not yet confirmed, but strategic implications are severe.Possible origin traced to compromised DoD stockpiles or third-party black-market suppliers.STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES:NA’s ultimate goal is not merely to replace the current government but to completely erase the institutional and ideological memory of the United States as it previously existed. In its place, it seeks to establish an authoritarian state based on struggle, loyalty, and purity of purpose.

Tactical Objectives Include:Destabilization of USMEA and civilian control zones through propaganda, assassination, and supply disruption.Expansion of Free State sympathizers into ideological alignment with NA doctrine.Subversion of local governance in isolated or underserved regions.Provocation of heavy-handed responses to fuel recruitment and validate revolutionary claims.RECOMMENDATIONS:Enhanced Psychological Operations to counter "Preacher" mythology and fracture ideological cohesion.Increased HUMINT penetration of Assembly-aligned cells and allied militias.Emergency review of chemical weapon security protocols at all surviving facilities.Development of ideological counter-narratives tailored to sympathetic civilian populations.Stricter vetting of civil-military personnel in affected regions for signs of ideological drift.ASSESSMENT CONCLUSION:New America is not merely a post-collapse insurgency. It is a revolutionary state-in-waiting – zealous, patient, and prepared to burn the remnants of the old world to build its own. Its greatest strength is ideological clarity, coupled with a deep resonance among the dispossessed. Its greatest vulnerability lies in its inflexible doctrine and reliance on centralized spiritual leadership. The longer USMEA fails to provide a clear and credible national future, the more New America’s message will resonate.

END OF REPORTDISTRIBUTION RESTRICTED: USMEA INTEL OPS CMD, MILGOV REGIONS 2–5, DCI FUSION NODE ALPHA

April 10, 2025

Campaign Updates: Politics By Other Means

As I mentioned last week, the Dolmenwood campaign is on hiatus until the end of this month. That means there will only be updates for the Barrett's Raiders and House of Worms campaigns. Fortunately, both campaigns provided plenty of action recently, especially House of Worms, where the struggle for who will succeed Hirkáne Tlakotáni upon the Petal Throne continues to heat up.Barrett's Raiders

As I mentioned last week, the Dolmenwood campaign is on hiatus until the end of this month. That means there will only be updates for the Barrett's Raiders and House of Worms campaigns. Fortunately, both campaigns provided plenty of action recently, especially House of Worms, where the struggle for who will succeed Hirkáne Tlakotáni upon the Petal Throne continues to heat up.Barrett's RaidersMichael and Radosław took the Ford F-150 truck (one of three vehicles assigned to MLG-7, the others being a LAV-25 and a Humvee) in the direction of the coded radio message Bum Farley had picked up. This led them to an obviously damaged roadside diner that had a ring of damaged cars around it. Sneaking up to it, Michael was able to ascertain three people – two inside the diner and one outside keeping watch, armed with an M16. While Radosław kept an eye on the guard, Michael slipped in the back, surprising the two inside. One was a woman and the other a man. After a brief moment of tension, Michael and the man exchanged pass phrases and countersigns that made it clear to each of them that they were both operatives of the CIA.

The man identified himself as Lee Gerber. He'd been doing deep cover work in Richmond, infiltrating the virulent Free State offshoot, New America, that had been growing in influence recently. When USMEA attacked, he only escaped thanks to Wyatt Henshaw, a Virginia National Guardsman and Dana Richter, a paramedic. They've been with him ever since, with Richter tending to cracked ribs he sustained prior to his escape. Neither one thinks much of USMEA, so Gerber was glad Michael didn't bring any soldiers with him. Gerber claimed to have sensitive information about New America, but wouldn't reveal it to Michael. Instead, he asked for a lift to the west side of Richmond, if possible. Michael couldn't do that – he was expected to rendezvous with Barrett's Raiders as they headed toward Fort Lee. Gerber was fine with that and asked to be dropped off, along with Henshaw and Richter, as far as Michael could take them. Meanwhile, Barrett's Raiders was make its way toward the I-295 interchange, which was as close to Richmond as they dared go. Captain Calloway had warned them against traveling near Richmond, as USMEA was not popular there. Because he hoped that Michael and Radosław would catch up with them before they headed southwards, Lt. Col. Orlowski ordered their vehicles to stop so that they could reconnoiter. Doing so proved smart. Up ahead, near the interchange, there were two vehicles, a Humvee and a black SUV, neither of which bore markings. With them were at least six soldiers, who likewise had no clear insignia on their uniforms. Worrying that they might be deserters turned marauders, Orlowski ordered Barrett's Raiders to avoid the highways and head south through smaller state roads.

Michael caught up with his comrades just before they left the highway. He also dropped off Gerber and his companions, wishing them luck. Gerber told him that, should he make contact with someone in the CIA, mention the name "Marcus Fallon" to them. It's important, he explained, and they'll know what to do with it. Now a full unit again, the group made their way south, stopping at the Varina-Enon Bridge over the James River, which was manned by a small detachment of military police from Fort Lee. The soldiers explained that the road was clear to the fort, but to stay buttoned up, because some of the locals liked to take potshots at passing USMEA vehicles. Orlowski thanked him for the advice and ordered the vehicles to continue their journey south.

House of Worms

Still reeling from the revelations regarding Prince Dhich'uné's plans, the characters tried to determine a way forward. Prince Táksuru admitted that he was simultaneously in awe of his half-brother's bold scheme and in fear that it might just work, securing eternal rule over Tsolyánu until the End of Time. Of course, not everyone was so sure that things would work the way Dhich'uné imagined. Chiyé in particular felt that Dhich'uné was deluded in thinking he could outwit the One Other and suggested that it might well give the pariah deity the means to become even more involved in the affairs of Tékumel – not a pleasant prospect!

There was also some discussion of certain similarities between Dhich'uné's plan and what had happened to Aíthfo some years ago. When Aíthfo died and was resurrected through Naqsái sorcery, he seemingly lost his Báletl or spirit-soul, which was replaced with the power of the god Eyenál. The worry now was that, if Dhich'uné sacrificed his spirit-soul to the One Other while emperor – even if he believed he could survive as an undead being – he risked providing an opening (literally!) to the One Other to inhabit him. Again, what this might mean remains unclear and it's precisely for that reason that the characters are so concerned. There were simply too many unknowns to Dhich'uné's gambit to allow him to pursue it. One way or the other, he had to be stopped.

Nebússa's wife, Srüna, arrived and asked her husband to forgive her for something she had done. She presented him with a sealed letter, bearing the seal of Princess Ma'ín. She explained that she had for years made use of a contact within a small local clan, the Green Smoke clan, who acted as middlemen for nobles and priests who wished to communicate discreetly. Her contact had intercepted this letter and thought it would be of interest, especially since it was headed for the clanhouse of the Domed Tomb clan, where Dhich'uné spent his time while in Béy Sü. The letter was a poem written in Classical Tsolyáni that, while in code, clearly suggested that Ma'ín wished to throw in with Dhich'uné, seeing him as the inevitable winner of the Kólumejàlim.

This concerned Táksuru, since his and Rereshqála's plan depended on all the other princes entering the Choosing of the Emperors in order to minimize the likelihood that Dhich'uné might win. While Ma'ín's odds were not good – she's a lover, not a fighter – her presence might still drain Dhich'uné's resources enough for others to defeat him. Srüna suggested substituting a fake letter for the one her contact intercepted, one that was more ambiguous and might undermine the burgeoning alliance between princess and prince. Nebússa agreed this was a good plan and made arrangements for it to happen.

Word also spread that Prince Eselné, who'd been absent from Béy Sü recently, would be entering the city in two days at the head of several cohorts of the First Legion, led by his friend and mentor, General Kéttukal. Ostensibly, this is a parade in honor of his deceased father, the emperor. However, Táksuru believes it's also intended as a provocation to Dhich'uné, a reminder that he has not yet won and that others are prepared to stand up to him. Eselné is not called the "Chlén-beast in blue robes" for nothing, after all!

More immediately pressing was the matter of Kirktá's golden disk. He still did not have it and, without it, he could not participate in the Kólumejàlim. The characters had earlier learned that it mostly likely lay somewhere within the Temple of Belkhánu where Kirktá had been trained as a young man. However, its precise location was unknown. Rather than directly looking for it, the characters opted to journey into Béy Sü's underworld beneath the temple, while Keléno's third wife, Mírsha, made use a locate object spell. Though the plan worked, revealing where the disk was likely located within the temple, it did draw the attention of temple guards in the underworld, who asked them to leave the area. Apparently, masked and robed men had been attempting to enter the temple from the underworld and now it was on alert against further incursions. Who these men were and what they wanted was yet another mystery.

April 9, 2025

Serious Fun: An Ode to GDW's RPGs

As I've said innumerable times since I started this blog, I was never a wargamer.

As I've said innumerable times since I started this blog, I was never a wargamer.I didn’t have shelves stocked with hex maps or spend my weekends calculating armor penetration on the Eastern Front. I wasn’t part of that sacred brotherhood that spoke in acronyms and argued over the effective range of a Panther’s 75mm gun. Yet somehow, whether by accident or by fate, I fell in love with a company born from that world: Game Designers’ Workshop, better known as GDW.

GDW got its start in 1973 as a publisher of serious, detail-oriented, historical wargames. While I didn’t know almost any of this when I first encountered their roleplaying games, I nevertheless felt it. Even as a teenager, I could tell there was something different about the games GDW made. Where TSR gave us magic missiles and gelatinous cubes, GDW gave us vector movement, speculative trade tables, and the quiet horror of running out of fuel in central Poland.

Like a lot of roleplayers, Traveller was the game that first introduced me to GDW. I came across it several years after playing Dungeons & Dragons, and the contrast was immediate. Traveller didn’t just offer you a character; it offered you a life. Character generation gave you a person with a backstory in the form of a career and an odd collection of skills and equipment. Of course, if your rolls were unlucky, all you got was an early grave before the campaign even began. This was the kind of game where you might end up as a grizzled ex-Merchant with a gambling habit and no pension instead of a mighty-thewed barbarian.

Traveller’s vision of the far future wasn’t shiny or triumphant. It was bureaucratic, complicated, and often rather gray. There was something fascinating about how it treated space travel not as an exciting novelty but as a job, equal parts dangerous, expensive, and frequently boring. It was, I later realized, a very wargamer approach to science fiction: not about wish fulfillment, but about systems, trade-offs, and consequences. Even though I’d never played Drang Nach Osten! or Pearl Harbor, I could still intuit that GDW’s RPGs were built by people who thought about conflict, logistics, and uncertainty in a fundamentally different way.

That sensibility was especially evident in

Twilight: 2000

. T2K was a game that asked, “What if the Cold War ended in fire and now you’re out of gas in a broken-down Humvee, trying to negotiate with a Polish farmer for potatoes?” It was bleak, but it was real. Every decision mattered. Ammo wasn’t just an abstraction; it was the difference between life and death. Characters had to eat, find shelter, manage morale. There were no magical solutions, just the grim satisfaction of surviving one more day.

That sensibility was especially evident in

Twilight: 2000

. T2K was a game that asked, “What if the Cold War ended in fire and now you’re out of gas in a broken-down Humvee, trying to negotiate with a Polish farmer for potatoes?” It was bleak, but it was real. Every decision mattered. Ammo wasn’t just an abstraction; it was the difference between life and death. Characters had to eat, find shelter, manage morale. There were no magical solutions, just the grim satisfaction of surviving one more day.I didn’t realize it at the time, but I think Twilight: 2000 taught me something about roleplaying that's stuck with me to this day: adventure doesn’t have to come from epic quests. Sometimes, it comes from the struggle to get by in the face of all sorts of obstacles, both big and small. Fixing a broken axle under sniper fire, bartering for antibiotics with a suspicious local, or just figuring out where the next meal is coming from. That was the adventure.

Later, I picked up Traveller: 2300 (later rebranded 2300 AD), which built on the ashes of Twilight: 2000's world to envision a future shaped not by utopian ideals, but by historical inertia. Nations rebuilt and space was colonized by corporations and governments with agendas rather than by high-minded dreamers. It wasn’t heroic, but it was plausible. It had an internal consistency that made it feel like a real place, even if that place was cold, indifferent, and occasionally French.

Then there was

Space: 1889

, GDW’s pioneering foray into what we'd now call "steampunk," complete with ether flyers, Martians, and an entire solar system shaped by European colonialism. Space: 1889 had a slightly lighter tone than its siblings, but it nevertheless bore the hallmark GDW seriousness. There was surprisingly detailed setting material, a respect for history, and a commitment to internal consistency that made its outlandish premise feel oddly plausible. Even in a world where Queen Victoria reigns over Venusian swamps, GDW still asked you to think like a colonial officer, an inventor, or an explorer navigating the realpolitik of empire.

Then there was

Space: 1889

, GDW’s pioneering foray into what we'd now call "steampunk," complete with ether flyers, Martians, and an entire solar system shaped by European colonialism. Space: 1889 had a slightly lighter tone than its siblings, but it nevertheless bore the hallmark GDW seriousness. There was surprisingly detailed setting material, a respect for history, and a commitment to internal consistency that made its outlandish premise feel oddly plausible. Even in a world where Queen Victoria reigns over Venusian swamps, GDW still asked you to think like a colonial officer, an inventor, or an explorer navigating the realpolitik of empire.Finally, there was Dark Conspiracy, a game that asked what would happen if you took the economic anxiety of the late '80s, mixed in extra-dimensional horror, and then handed the whole mess to a security contractor. As I mentioned in my recent Retrospective, Dark Conspiracy failed to live up to its full potential, but even so, it was strangely compelling. Beneath the neon-soaked dystopia and monstrous invaders, you could still feel GDW’s trademark seriousness at work: the emphasis on gear, tactics, and systems that made survival feel earned rather than assumed.

What bound all these games together wasn’t genre; it was approach. GDW brought a wargamer’s eye to RPGs. They cared about detail, about systems that worked even when they weren’t elegant (though I continue to maintain that Traveller is one of the most mechanically elegant roleplaying games ever designed). GDW wasn't afraid to make things difficult or even bleak, because they believed that challenge and immersion went hand in hand. As a player and a referee, I must confess that I didn’t always understand every rule. I sometimes made do with what I thought they meant, but I nevertheless respected the intent. GDW’s RPGs weren’t about wish fulfillment. They assumed you were already smart enough to navigate their worlds and tough enough to handle the consequences.

As someone who entered the hobby on the more fantastical side represented by D&D and

Gamma World

, that was both refreshing and bracing. GDW showed me that roleplaying could be serious, by which I don't mean dour, but serious in the best possible way. Roleplaying games could provoke you to think, to plan, and to inhabit a world that didn’t care about your character sheet unless you used it wisely.So, as I said at the beginning of this post, I was never a wargamer, but I was – and remain – a GDW fanboy. Their RPGs showed me a different way to play, a way shaped by history, consequence, and thought. Almost thirty years after the demise of the company, that kind of grounded imagination still feels like something worth celebrating, hence today's ode to the amazing roleplaying games of Game Designers' Workshop. What an incredible company, what an incredible library of games.

As someone who entered the hobby on the more fantastical side represented by D&D and

Gamma World

, that was both refreshing and bracing. GDW showed me that roleplaying could be serious, by which I don't mean dour, but serious in the best possible way. Roleplaying games could provoke you to think, to plan, and to inhabit a world that didn’t care about your character sheet unless you used it wisely.So, as I said at the beginning of this post, I was never a wargamer, but I was – and remain – a GDW fanboy. Their RPGs showed me a different way to play, a way shaped by history, consequence, and thought. Almost thirty years after the demise of the company, that kind of grounded imagination still feels like something worth celebrating, hence today's ode to the amazing roleplaying games of Game Designers' Workshop. What an incredible company, what an incredible library of games.

April 8, 2025

Retrospective: Merc: 2000

The last six months of 1989 marked the beginning of the end of Communism in Eastern Europe and, with it, the Cold War. Between June, when Solidarity won Poland's first semi-free elections in decades and the execution of Nicolae Ceaușescu in late December – not to mention the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9 – the world that had existed since 1945 unraveled in real time. These momentous events ushered in what U.S. president George H.W. Bush optimistically dubbed the “new world order.” For a time, many breathed a sigh of relief.

At Game Designers’ Workshop in Bloomington, Illinois, though, the end of the Cold War created a creative dilemma. Their military RPG Twilight: 2000 was built on a dark, alternate history premise: détente had failed, nuclear war had erupted, and civilization lay in ruins. Now that reality had taken a different path, that premise was suddenly obsolete. Line developer Loren Wiseman didn’t throw in the towel but instead adapted.

Merc: 2000, released in 1990, was his answer.

Rather than pivot away from military adventure, Merc: 2000 reimagined a world where the Cold War ends more or less peacefully, as it had in reality, but the peace is shallow. The Soviet Union lingers in a diminished state, the Third World seethes with brushfire wars, and the major powers, unwilling to commit their own troops, outsource dirty work to deniable assets. Enter the player characters as mercenaries for hire, plying their trade in a world where “peace” is just another illusion and every war is someone's business opportunity.

In hindsight, Merc: 2000 reads as much as a nervous exhalation from a culture suddenly unsure of who the enemy is as a RPG supplement. To varying degrees, it captures the jittery uncertainty of the early ’90s, when ideology faded but the machinery of conflict kept humming. If Twilight: 2000 was a fever dream of what might have been, Merc: 2000 was a grim-eyed projection of what was coming.

And it wasn’t wrong.

The setting anticipates the rise of private military contractors, the shadow wars of the post-9/11 era, and the morally murky interventions of the ’90s, such as Somalia, the Balkans, and the Persian Gulf, among too many others. It imagines a world of porous borders, covert missions, and soldiers who work for paychecks, not flags. Its tone of weary professionalism, competence without cause, sets it apart from the more operatic tone of Twilight: 2000. In some ways, I'd go so far as to say it's aged better.

That said, Merc: 2000 isn't a standalone game. It builds directly on Twilight: 2000's second edition, also released in 1990, and inherits both its strengths and its spiky complexity: crunchy mechanics, detailed equipment lists, and an emphasis on logistics, firearms, and realism. If you liked T2K’s obsessive attention to detail, you’ll find plenty to enjoy here. If not, Merc probably won’t change your mind.

What distinguishes it is scope. Where Twilight: 2000 offered survival in a wrecked Europe (and, later, America), Merc: 2000 gives you the world. Campaigns can explore corporate espionage, peacekeeping gone wrong, proxy wars, failed states, and morally ambiguous black ops. It opens the door to adventures that blend military action with politics, ideology, and personal cost, offering a sandbox of plausible deniability and ethical compromise.

From today’s perspective, what stands out most is how little Merc: 2000 glamorizes its subject. There are no grand causes, just contracts. No crusades, only jobs. In that, it feels oddly prophetic. It foresaw a world where war became a business and soldiers became freelancers in the global gig economy of violence.

Unlike Twilight: 2000, which I played quite a bit, I never had the chance to run Merc: 2000 back in the day. By the time it came out, I’d already drifted away from T2K, thinking the real world had outpaced it. Ironically, as my Barrett’s Raiders campaign heads back to the USA, I realize how much of Merc: 2000 has seeped into my imagination after all, particularly in the types of missions, the tone, and the sense of purpose frayed by compromise that now animate that campaign.

Thirty-five years on, I think more highly of Merc: 2000 than I probably did upon its publication, not because, like Twilight: 2000, it depicted a world that never was, but rather because it depicted one we hadn’t yet admitted we were already living in.April 7, 2025

The Articles of Dragon: "New Denizens of Devildom"

I'm sure it'll come as no surprise that issue #75 of Dragon (July 1983) is among my favorites, one I both remember very well (and for which I, therefore, have a great deal of nostalgia) and one whose content was of very high quality. Indeed, I'd go so far as to say that the run of issues between, say, issue #65 (September 1982) and issue #100 (August 1985) may well have been the magazine's best ever. I'm biased, of course, since this run not coincidentally coincides with when I subscribed to Dragon, but I really do think that, from a reasonably objective perspective, that three-year period was exceptional, filled with some of the most interesting and inspiring articles ever to grace Dragon's pages.

I'm sure it'll come as no surprise that issue #75 of Dragon (July 1983) is among my favorites, one I both remember very well (and for which I, therefore, have a great deal of nostalgia) and one whose content was of very high quality. Indeed, I'd go so far as to say that the run of issues between, say, issue #65 (September 1982) and issue #100 (August 1985) may well have been the magazine's best ever. I'm biased, of course, since this run not coincidentally coincides with when I subscribed to Dragon, but I really do think that, from a reasonably objective perspective, that three-year period was exceptional, filled with some of the most interesting and inspiring articles ever to grace Dragon's pages.Issue #75 is probably best remembered for the first part of Ed Greenwood's superb treatment of the Nine Hells and rightly so. What people sometimes forget is that the issue also included a partial preview of the upcoming Monster Manual II in Gary Gygax's regular "From the Sorcerer's Scroll" column. In fact, I believe it was precisely because of the planned appearance of this preview that Greenwood was given the go-ahead – with Gygax's blessing – to develop the Nine Hells as an adventuring locale suitable for use with AD&D.

Over the course of six pages, Gygax provides game statistics for a plethora of new devils, both generic and specific. The generic ones are notable, in that they run the gamut of hit dice, from the 3 HD spined devils to 8 HD black abishai. While AD&D had always included weaker devils and demons as opponents, I know that, as a younger person, I appreciated the addition of more at the lower end of the diabolic spectrum. Devils, as envisaged by Gygax, have always been compelling enemies to me, but they were mostly the enemies for higher-level characters, given their hit dice and powers. By including more options at the low end, Gygax made it easier for me to use them with a wider range of character levels.

Of course, the true stars of this article (and the Monster Manual II) were the specific, named devils, including several new arch-devils. This pleased me greatly back in the day. The original Monster Manual was the very first AD&D book I ever owned. I bought it at a Sears catalog store in early 1980, using money I'd got for Christmas and I spent an inordinate amount of time poring over its pages. One of the things that I soon noticed was that Gygax hadn't provided entries for all the arch-devils ruling over Hell's nine planes. Who ruled over the third and fourth layers? And what about the eighth, the one closest to the domain of Asmodeus? This article finally answered some of these questions.

Beyond new arch-devils, "New Denizens of Devildom" also gave us "dukes of hell" – singular named devils with unique statistics that were beneath the arch-devils in both authority and power. That last part was especially important, because it meant that there was now space for powerful, named devil opponents who weren't as potent as the rulers of Hell's layers. This was a terrific boon to me and my campaign, though my players back then might have disagreed! Another great aspect of these additions was that they could be defeated and even slain by player characters without worrying about how this might upset the cosmic balance of the Outer Planes.

This is one of those articles that is probably hard to appreciate decades after its initial publication. Nowadays, almost nothing within its six pages is all that notable, its information having long since passed into general Dungeons & Dragons lore. But, during the summer of 1983, several months before the Monster Manual II would be available for purchase, an article like this captivated me immensely. I was seized by the possibilities it presented and the directions it suggested Gygax was planning to take AD&D in future. Consequently, it remains an affectionate favorite of mine, even if it's unlikely to make most people's Top 10 – or Top 50! – lists of Dragon's greatest articles.

Esoterica

My apologies to anyone not particularly interested in the Tékumel setting, which is the backdrop for my long-running House of Worms campaign. As this campaign races toward its conclusion after more than a decade of play, the stakes are rising. The characters are now uncovering some of the setting’s deeper mysteries—those that are either well hidden or not addressed at all in published materials. Fortunately, I’m both deeply familiar with Tékumel’s arcana and quite willing to deviate from it when doing so enhances the fun. That’s why I’m hopeful that the campaign’s final denouement will be a satisfying one.

In my most recent campaign update, I referenced several elements that may not be immediately clear or that deserve further explanation. Let’s begin with the Tsolyáni conception of the soul, which is largely inherited from the earlier Engsvanyáli civilization. According to this worldview, the soul is composed of five distinct parts:

Bákte: the physical body, which is born, lives, grows, dies, and returns to dust.Chusétl: the "shadow self," the sleeping counterpart of the waking person, which exists in dreams.Hlákme: the conscious mind, encompassing both intellect and ego: the “I-ness” of a person.Pedhétl: the bundle of raw instincts, lusts, fears, and desires, as well as the source of psychic power.Báletl: the spirit-soul, which travels after death to the Isles of the Excellent Dead before eventually being reborn.Different gods and religious sects in Tsolyánu emphasize certain aspects of the soul over others. In the case of the Temple of Sárku, the Change deity of death, only the body and the intellect truly matter. Everything else is considered irrelevant. For Sárku’s worshipers, the intellect (or ego) is the essence of individuality, that which separates one person from another. Normally, this aspect ceases to exist upon death. The only part of the soul that survives is the Báletl, the spirit-soul, which is not truly individuated and is eventually reborn in someone else, without any memory of its previous existence. To a devotee of Sárku, this outcome is abhorrent. Thus, they embrace a sorcerous union of the body and intellect after death by becoming undead.

This is what makes Prince Dhich’uné’s plan, as described in the linked update, comprehensible. He seeks to ascend the Petal Throne, become emperor, and then offer his spirit-soul as a sacrifice to the pariah deity known as the One Other, because he sees no value in that part of his soul. Instead, he intends to preserve his body and mind as an undying emperor. This “exquisite gift” to the One Other, he believes, will secure for Tsolyánu a state of perpetual stability, allowing it to avoid the fate of all previous empires, including the ever-glorious Engsvanyáli Imperium.

Why does he believe this? Dhich’uné claims to have uncovered a dark secret: that the founder of the Tsolyáni Empire was a cultist of the One Other. The name of the first emperor is unrecorded; he is known only as “the Tlakotáni.” This name eventually became the clan name of the imperial line. However, anyone familiar with Engsvanyáli, the language from which Tsolyáni descends, knows that tlakotané means “brother,” but not in the familial sense. Rather, it denotes brotherhood in a priesthood or secret society. So, to which secret society did the first emperor belong? According to Dhich’uné: a cult of the One Other.

What evidence Dhich’uné has for this claim is not yet clear. However, the mystery surrounding the identity and nature of the first emperor is certainly suggestive. Moreover, although the worship of the One Other. like that of all pariah gods. is officially banned in Tsolyánu, his priests operate in secret within the Temple of Belkhánu. Even more curiously, they play a formal role in the emperor’s internment rites. Why, then, the public disavowal of the One Other, while simultaneously granting his priests a hidden role at the heart of imperial ritual? Dhich’uné believes he knows the answer: the empire was founded and sustained by a covenant with the pariah god, one that is continually renewed through the sacrifice of the spirit-souls of those who lose the Kólumejàlim (the Choosing of the Emperors).

Dhich’uné now believes he can reshape that covenant. Instead of the traditional sacrifice of defeated princes, he proposes to offer the spirit-soul of an emperor. He believes this will vastly strengthen the stabilizing influence of the One Other, making it eternal. He also believes that by becoming undead, he can survive the loss of his spirit-soul. Of course, no one can know whether this gambit will succeed, but Dhich’uné is convinced it will. He believes he has the knowledge and the will to deceive a pariah god into giving him what he desires.

Whether he’s right forms the central question of the campaign’s next (and likely final) phase.

Mongoose Acquires Dark Conspiracy

Serendipity is a real thing. When I decided last week to write a Retrospective post about GDW's 1991 horror RPG, Dark Conspiracy, I had no advanced knowledge of today's announcement that Mongoose Publishing has acquired all the rights to it. This isn't exactly surprising. Once it was announced last summer that the company now owned the rights to Traveller (along with Twilight: 2000), I thought it inevitable that they'd also grab the rights to other former GDW properties. Still, it's nevertheless an odd little coincidence that I started thinking again about DarkCon after all these years.

According to the limited information available, Mongoose's re-release of the game won't be until next year. There's no official word on its rules, but I'd be amazed if it didn't use some version of the Mongoose Traveller rules, which are rapidly becoming the house system of the company. I'm fine with that, honestly. For all my complaints about the most recent iteration of the Mongoose rules, it's still a solid system and much better than Dark Conspiracy's original rules, which I never much liked.When I hear more, I'll be sure to share that information here.

April 6, 2025

I Hate Combat

Here’s a confession that might get me kicked out of the old school clubhouse: I hate combat in roleplaying games.

There: I said it.

Now, I’m – obviously – not saying combat never has a place at the table. I've refereed sessions where battles were tense, dramatic, and even thrilling, with cunning ambushes, panicked melees in cramped spaces, last-stand battles with high stakes for all those involved. If you want, I can recount plenty of examples of fun, memorable combats from almost any campaign I've run in recent years (and some from well before that). However, those are the exceptions, the golden flecks in the gravel.

Most of the time, combat is the broccoli on my RPG dinner plate, something I chew through dutifully because I’m told it’s good for me. This is especially true when I'm refereeing games like Dungeons & Dragons and its descendants, which tend to highlight combat. From what I can tell, other people seem to genuinely like combat. After all, it’s in every rulebook and often takes up its longest chapter. Combat's part of a balanced adventuring diet, isn’t it?

And yet I regularly find it tedious.

Roll to hit. Miss. Roll to hit. Miss. Roll damage. Deduct hit points. Wait. Roll to hit. Miss. Consult a chart. Roll to confirm. Miss again. Meanwhile, someone's scrolling through social media. Combat grinds on, a clockwork of attrition that slows down the pace of the session. The usual momentum of exploration, intrigue, or even character banter gives way to a wargame that’s usually just complex enough to bog things down but not complex enough to be tactically interesting.

I know this sounds like sacrilege, especially coming from someone who inhabits the old school part of the hobby, where monsters are there to be slain and treasure to be pried from their still-warm claws. But even when I was a kid, the parts of a session I looked forward to weren’t the whittling down of hit points or the tracking of initiative. They were everything else.

I loved describing sinister rooms filled with strange objects and watching my friends debate whether or not to touch them. I loved watching them argue about the safest way for their characters to cross a rickety rope bridge across a chasm. I loved their paranoid investigations of hidden crawlspaces and their impromptu diplomacy with bullywugs they were trying to convince of their good intentions (I should write about that sometime). I loved the awkward, funny, surprisingly human interactions between characters and the worlds I'd presented to them.

That’s always been the meat of roleplaying games for me: not the fighting, but the playing. Heck, that's why I'm still here after all these years.

To be clear: I love a good fight. In fact, as a player, I really respect a well-run tactical encounter and have nothing but praise for referees capable of this. A few years ago, for example, I played in a great Rolemaster campaign run by a friend who knew the game – and its combat rules – like the back of his hand. I left that campaign with a much greater appreciation for the unique virtues of Rolemaster and its chart-driven approach to combat. It helped, too, that the referee had a good sense of how to make combats fun, a skill in which I am decidedly lacking.

I often include combats because I feel obligated to do so. Of late, I've noticed this most often in my Barrett's Raiders Twilight: 2000 campaign. Since T2K is a military RPG, it would be ridiculous not to have combats, wouldn't it? So, we have them, even though I spend most sessions trying to figure out ways to avoid them. Again, it's not that we haven't had fun and exciting combats in that campaign, because I know we have. However, they're not what interest me and I regularly feel as if combat doesn't play to my strengths as a referee.

Consequently, I sometimes think of combat as a tax I have to pay to get to the good parts of the session, like those unskippable ads on YouTube, except the ads last half an hour and require me to reread the rules on incendiary ammunition. Again.

Now, I understand that some people love combat. For some, it’s what they most enjoy about RPGs. There’s a satisfying clarity in the geometry of battle, the crisp chain of cause and effect, the tactical puzzle. I completely understand that, because, as I said, I've had moments where I felt the same way. So, I salute their enthusiasm. I merely ask that they might forgive me when I can't be bothered to remember the modifier for an attack against a prone target or how much protection a concrete wall provides against weapons fire.

For me, the real excitement comes when players sidestep combat entirely. When they parley, sneak, bribe, confuse, seduce, or otherwise avoid having to resort to swordplay or gunfire. Not only do I cheer those moments for the cleverness they demonstrate, but also because it means I don't have to worry about my own tactical inadequacies. Plus, it's in the unscripted non-combat interactions that the game feels most alive to me.

So, yes, I hate combat – but only because I love everything else about roleplaying games so much more.

Still, just often enough to make me question everything, a combat shines. The dice align, the stakes are high, the players are desperate, and suddenly we’re not just resolving a skirmish. We’re there, holding our collective breaths, waiting for the next roll. In those moments, I’m reminded why people put up with those incendiary ammunition rules.

But I won’t pretend I’m not secretly hoping someone talks their way out of it instead.James Maliszewski's Blog

- James Maliszewski's profile

- 3 followers