Edward Willett's Blog, page 55

March 19, 2012

Salt-tolerant wheat

Having grown up on the prairies, first in Texas, then in Saskatchewan, I've seen, my whole life, the patches of white where nothing grows, out in the middle of the fields. And like most other prairie folk, I've tended to call them "alkali."

Having grown up on the prairies, first in Texas, then in Saskatchewan, I've seen, my whole life, the patches of white where nothing grows, out in the middle of the fields. And like most other prairie folk, I've tended to call them "alkali."

Fact is, though, that most of them, at least in Saskatchewan, aren't alkaline at all, but saline. True alkaline soils are low in soluble salts, but have a high sodium content and a high pH (over 8.5, which falls between egg whites and ammonia on the alkaline side of the pH ledger).

Saline soils are those with a lot of soluble salts in them, and although estimates vary widely, it's generally agreed that several million acres of Saskatchewan soil are affected by salinity to some degree, with some 600,000 acres within the cultivated area of the province so badly affected they have zero productivity.

Saline soil makes life difficult for plants because it deprives them of water. In ordinary soil, salt in the sap in plant roots draws water (and dissolved nutrients) into the plant via osmotic pressure. When the water in the soil is also salty, that pressure is reduced and water doesn't flow into the root, slowly starving the plant. In addition, sodium can build up in the plant's leaves, interfering with photosynthesis and other important processes.

Saline soils are bad news wherever they occur, and they occur everywhere: it's estimated that more than 20 percent of the world's agricultural soils are affected. They're a particular problem in the wheat-growing areas of Australia, which is the world's second-largest wheat exporter after the United States. (What, you thought that was Canada? No, we actually rank fourth, behind Russia, and just ahead of the European Union.)

The gene pool of modern wheat is rather narrow, thanks to domestication and breeding over the years, which has made it vulnerable to environmental stress. Durum wheat, which is used for pasta, among other food products, is particularly susceptible to soil salinity.

But now researchers at CSIRO Plant Industry in Clayton South, in the Australian province of Victoria, have successfully bred salt tolerance into a variety of durum wheat so effectively that it shows an improved grain yield of 25 percent on salty soils.

And even if you're dead-set against genetically modified wheat, you needn't throw up your hands in horror: this improved variety was created using non-GM crop-breeding techniques. Not only that, but the scientists at the University of Adelaide's Waite Research Institute are digging deeper into the plant to discover exactly how salt tolerance works genetically.

It all comes down to a salt-tolerant gene (TmHKT1;5-A, if you must know) which produces a protein that removes the sodium from the cells lining the xylem, the "pipes" that move water from the plant's roots to its leaves.

The gene was discovered in an ancestral cousin of modern-day wheat called Triticum monococcum (as a Star Trek geek, I wish it was called quadrotriticale, but alas…). Through a selective breeding process, they were able to introduce that gene into a variety of durum. In field trials at a variety of sites across Australia, not only did the new salt-tolerant durum outperform its parent under salty conditions by up to 25 percent, it performed the same as its parent under normal conditions.

"This is very important to farmers, because it means they would only need to plan one type of seed in a paddock that may have some salty sections," points out Richard James, lead author of the CSIRO Plant Industry study, which was published last week in Nature Biotechnology.

The new version of durum will now be used by the Australian Durum Wheat Improvement Program to see what the impact will be of incorporating it into recently developed varieties as a breeding line.

That means new varieties of salt-tolerant durum wheat could soon be available commercially—and since it was created through a non-GM breeding process, it can be planted without any of the restrictions sometimes placed on GM varieties.

Nor is salt-tolerant durum the end of the road for the research. The scientists have already bred the salt-tolerance gene into the kind of wheat used to make bread. It, too, is currently undergoing field trials.

The world population continues to grow, and that means a growing demand for food…which could make salt-tolerant varieties of wheat immensely valuable in the decades to come: not just in Australia, but right here at home.

(The photo: a particularly salt-tolerant variety of wheat in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, although it is rather susceptible to rust.)

March 17, 2012

Saturday Special From the Vaults: Introduction to Jimi Hendrix: Kiss the Sky

For several years I wrote numerous non-fiction books for Enslow Publishers, ranging from science books to biographies. Among the biographies were four for a series called American Rebels, for which I wrote books on Johnny Cash, Janis Joplin, Andy Warhol…and Jimi Hendrix.

For several years I wrote numerous non-fiction books for Enslow Publishers, ranging from science books to biographies. Among the biographies were four for a series called American Rebels, for which I wrote books on Johnny Cash, Janis Joplin, Andy Warhol…and Jimi Hendrix.

For this week's Saturday special, the introduction (complete with footnotes!) to Jimi Hendrix: Kiss the Sky . Which you can purchase here, if you're interested!

**

Jimi Hendrix: Kiss the Sky

By Edward Willett

Introduction

Shortly after 9 a.m. on Saturday, September 24, 1966, a young black man stepped off a Pan American Airlines airplane at London's Heathrow Airport. All he had with him was $40 in borrowed cash, a small bag containing a change of clothes, pink plastic hair curlers and a jar of Valderma face cream…and his guitar.[i]

But a guitar was all he really needed. Within an extraordinarily short time, that young man would be famous around the world. Decades later, he's still famous: "King Jimi," a "guitar god," the "master of electric-guitar sound and style."[ii]

Later that same evening, Jimi Hendrix was onstage at The Scotch of St. James, a club that attracted people in the music industry. As he started to play, the club fell silent.

"He was just amazing," Kathy Etchingham, then just twenty-four and soon to be Jimi's girlfriend (one of many), recalled. "People had never seen anything like it."[iii]

Among the musicians in the crowd was Eric Burdon of the Animals. His take: "It was haunting how good he was. You just stopped and watched."[iv]

Burdon was the first famous guitarist to be awed by Hendrix's ability. He wouldn't be the last. On January 11, 1967, Hendrix and his new band, The Experience, played at a basement club called the Bag O'Nails in the Soho district of London.

Hendrix had been in England just three and a half months (and had spent several weeks touring France and Germany with the Experience), but that night his show was attended by rock greats Pete Townshend and John Entwhistle of the Who, John Lennon, Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr of the Beatles (plus their manager, Brian Epstein), Mick Jagger and Brian Jones of The Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck…and many others.[v]

People all over the world stopped and watched when Jimi Hendrix played…but it all ended on September 18, 1970, when he died in London at the age of twenty-seven.

Jimi Hendrix crammed a lot into his short life. The consummate rebel, he somehow fought his way past every barrier that rose between him and his lifelong dream of stardom. He rebelled against his father, who thought his music was a waste of time. He rebelled against the strict regimentation of the bands in which he played as a back-up guitarist. He rebelled against the expectation that he would limit himself to playing for black audiences. He rebelled against conventional notions of how the electric guitar should be played. He rebelled against conventional ideas of sexual morality. And, tragically and fatally, he rebelled against restrictions on his use of drugs.

Tony Palmer, a friend of Hendrix's who today is a renowned director of music documentaries, wrote in The Observer newspaper on September 20, 1970, "Whatever Mozart and Tchaikovsky have come to mean to lovers of classical music, Hendrix meant the same if not more to a whole generation."[vi] He added, "Jimi Hendrix was born Jimi Hendrix. Great musicians are not created; they are born. Jimi was meant for music."[vii]

Looking back, it seems as if Jimi Hendrix was always meant to be a star. Certainly he always thought so. But for most of his life, stardom seemed a very long way away…

INTRODUCTION

[i] Cross, Charles R., Room Full of Mirrors: A Biography of Jimi Hendrix, New York: Hyperion, 2005, pp. 153-154.

[ii] Potash, Chris, ed., The Jimi Hendrix Companion: Three Decades of Commentary, New York: Schirmer Books, 1996, pp. xv, xviii.

[iii] Cross, p. 136.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid, pp. 176-177.

[vi] Lawrence, Sharon, Jimi Hendrix: the Man, the Magic, the Truth, New York: HarperEntertainment, 2005, p. 217.

[vii] Ibid., p. 322.

*

March 12, 2012

Plate tectonics

Our planet may look like a solid ball of rock, but if you could crack it like an egg (not actually something I'd recommend, although it would make for a fun scene in a science fiction novel or movie) you'd find it's quite fluid inside.

Our planet may look like a solid ball of rock, but if you could crack it like an egg (not actually something I'd recommend, although it would make for a fun scene in a science fiction novel or movie) you'd find it's quite fluid inside.

And, in fact, the Earth's solid shell, called the lithosphere, is cracked: broken up into numerous "tectonic plates" that scoot around on top of the more fluid layer beneath, called the asthenosphere.

Well, "scoot" might be an overstatement: plate speeds range from around 10 millimeters a year all the way up to a whopping 160 millimeters a year (about as fast as your hair grows).

This means Earth's oceans and continents are constantly changing shape, and if that sounds just a little bit crazy even today, think how it sounded a century ago when meteorologist Alfred Wegener put forth his notion of "continental drift," a theory he expanded in a 1915 book, The Origin of Continents and Oceans.

Wegener wasn't the first person to posit something of the kind (after all, he was hardly the first to notice that South America and Africa look uncannily like two pieces of a jigsaw puzzle separated by a few thousand miles of ocean), but he put forward as solid an argument as could be managed at the time, pointing to the similarity of rock formations on the east coast of South America and the west coast of Africa, fossils shared by South America, Antarctica, India and Australia, and more.

But it took a slow accumulation of additional evidence over the next few decades to convince the bulk of the geological community of the fact of continental drift. One reason was that nobody could quite figure out how, exactly, pieces of crust could move around. Certainly Wegener's concept of the continents as "icebergs" of low-density granite floating in a "sea" of denser basalt didn't seem adequate to explain the phenomenon.

Eventually, though, the evidence became overwhelming, and plate tectonics, as it became known, took its rightful place as central to the proper understanding of earth's geological history. (Though not, alas, in time for Wegener to see his "crazy" notion properly vindicated: he died in 1930.)

The wholesale shifting around of continents appears to have gotten underway about three billion years ago, and three times since then, all of the continents have mushed together into a single supercontinent. The most recent of these, called Pangaea, only broke apart about 250 million years ago, eventually creating the familiar shapes you memorized in geography.

In some places ("divergent boundaries"), the plates are pulling apart. Rock from the asthenosphere rises to the surface and becomes new lithosphere, mostly in the middle of the oceans, where this forms enormous rifts.

In other places ("convergent boundaries") the plates are running into each other. In some places, this results in subduction, with one plate being forced under the other. In the ocean, this creates deep trenches. As one plate is driven deeper into the Earth, it heats up and fluids within it melt the surrounding rock, creating magma that feeds volcanoes like those of the famous Ring of Fire that surrounds the Pacific Plate. When two continents run into each other, mountains—for example, the Himalayas—are forced up.

The constant upwelling of rock at the divergent boundaries and sinking of rock at the convergent boundaries creates a conveyor-belt effect that is the main force driving the movement of the plates.

In some regions ("transform boundaries"), plates aren't running into each other or pulling apart from each other: they're just rubbing each other the wrong way. The best-known example is the San Andreas Fault. As the plates grind together they generate earthquakes.

There are seven major plates—the African Plate, the Antarctic Plate, the Indo-Australian Plate, the Eurasian Plate, the North American Plate, the South American Plate, and the Pacific Plate—and dozens of smaller plates, all constantly in motion.

Which means you shouldn't get too attached to that map of the world you memorized. In 250 million years, after all, schoolchildren (or, at least, schoolthings) living on the new supercontinent Pangaea Ultima may well look back at our era and laugh at the strange shapes of our fragmented world.

(The image: The aftermath of colliding plates, a.k.a. the Canadian Rockies.)

March 10, 2012

Saturday Special from the Vaults: The Minstrel

This week, another early story of mine. This is one of the earliest stories I sold, to a long-defunct Canadian children's magazine called JAM . In fact, it was the cover story, and if I ever figure out where I put the magazine I'll post the cover art here.

It's of roughly the same era as "Janitor Work," which I posted here a few weeks ago.

The other interesting thing about "The Minstrel": it was the basis for my first post-university novel, a book that never sold…but that came agonizingly close, as I found out at the World Science Fiction Convention in Winnipeg in 1994. Josepha Sherman was editing science fiction at Walker & Co. in the late 1980s early 1990s (I don't remember the precise dates) and I'd sent the novel version of this story to her. She liked it, but said it needed quite a bit of additional work…which I did, adding several chapters, in fact. I sent it back, but again it was turned down.

What I found out in Winnipeg, as she recounted the tale while on a panel, was that she'd been "ready to make an offer"…but then the publisher died and his replacement decreed that Walker would no longer publish science fiction. And so my novel-writing career remained stalled for many more years.

Such is life, and writing. But I've got plans to go over Star Song (as I eventually titled the novel) and release it myself as an ebook. So I may yet have the last laugh!

For now, enjoy "The Minstrel."

###

The Minstrel

By Edward Willett

The music sang of the infinite Dark and the suns that burn within it. It shimmered like starlight on alien seas, and whispered with the voices of strange winds.

#

Kriss stopped playing, and as the last chord died slowly away, sat quietly with his head bowed, cradling his touchlyre in his arms. The orange glow of the oil lamps gleamed on the instrument's polished black wood and burnished copper.

One by one those in the smoky bar, mostly offworlders, rose from their tables and came to the low platform where Kriss sat to drop coins into the wooden bowl at his feet. The murmur of their conversation was slow to resume.

When the last had come and gone Kriss stood, bowed, and left the stage. He divided the money with the innkeeper, then slipped the touchlyre into its soft leather case and went out into the chill night air.

In the cobblestoned street he stopped and looked up at the stars blazing in the night sky, as he did every evening when he finished playing, burning into his mind's eye the goal for which he had striven, it seemed, forever.

Two local men staggered by. One poked the other with his elbow and nodded toward Kriss. "Uppity offworlder," he whispered loudly. His companion made an obscene gesture at the boy, then, laughing, they weaved on down the street.

Kriss clenched his fists, then spun and strode in the opposite direction.

Where the cobblestones ended and concrete began, artificial lights banished the night. At the sight of them Kriss forgot the drunks' insults and broke into a run. In a moment he reached the tall wire fence that surrounded the spaceport and pressed his face against the cold mesh, peering through it at the starships, silver spires that seemed to soar skyward even though standing still. The lights glittered on their mirrored sides.

There lay the path to the stars, away from this hated planet where he didn't belong, couldn't belong, though he had been raised on it. The drunks had known; they had seen his height and his blonde hair and had known he came from the stars.

Somewhere out there must be his true home; somewhere out there he had to have a family. His parents were dead, but they had to have had parents of their own, brothers, sisters…

He blinked away tears, and, disgusted with his own self-pity, turned away from the fence and set out along a dark, garbage-strewn alley for his barren lodging, a tiny attic room above a seamstress's shop. He was fooling himself if he thought he would ever leave Farr's World, he thought bitterly. The spacecrews called him "worldhugger"; neither Union nor Family, and without contacts in either of those spacefaring groups, he could never gain a berth as a crewmember, and he could entertain in spaceport bars for the rest of his life without raising enough money to buy passage into orbit, much less to another world.

Lost in dark thoughts, he didn't realize he was being followed until a hand touched his shoulder.

He instinctively spun away from that touch and pressed his back against a rough stone wall, his heart pounding, his arms wrapped protectively around the touchlyre.

"I mean you no harm," said the man who faced him. Shadows hid his features. "I only want to talk."

Kriss did not relax. "Then talk."

"What is your name?"

Kriss said nothing.

"Perhaps if you knew mine…? I am Carl Vorlick, a dealer in alien curiosities." He waited.

"My name's Kriss Lemarc," Kriss said finally. "Why?"

Vorlick ignored the question. "And how old are you?"

"Fifteen, standard."

"That would be just about right." Vorlick's eyes glinted faintly in the starlight. "I heard you play in Andru's—remarkable. Almost as though you projected emotion, not just sound."

Pleased despite himself, Kriss shrugged. "My instrument is…special."

"Indeed it is. And very beautiful. May I…?" He held out his hand.

Kriss looked up and down the alley, but saw no hope of rescue. Slowly he unfolded the leather covering and took out the touchlyre. The copper fingerplates and strings shone even in that dark corner.

Vorlick took a handlight from his pocket and played the beam over the instrument. Kriss caught a quick glimpse of a lean face with thin lips and ice-blue eyes before the light switched off. "Lovely," the man murmured. "How does it work?"

Kriss hesitated. "I hear music in my mind, and the touchlyre plays it," he said finally. "I can't explain any better than that."

"Touchlyre?"

"That's what I call it. I don't know what its real name is."

"Where did it come from?"

"It belonged to my parents. But I don't even remember them."

"Your parents, yes." Vorlick paused for a long moment, then said, "You desire to leave this world, don't you?"

Kriss said nothing. This stranger knew too much. Once again he glanced up and down the alley. He would have welcomed even the two drunks who had insulted him earlier—but there was no one.

But Vorlick took his silence as consent. "I own a ship."

Kriss stiffened. "What do you want from me?" he demanded; but inside he already knew.

"The price is small: your instrument. Give the touchlyre to me, and I will take you into space."

Kriss looked down at the touchlyre. "It's that valuable?"

"To the right person, everything is valuable. Your music spoke of your longing for the stars—some of those hardened spacefarers in Andru's were near tears. You value the stars, I value your instrument. A fair exchange."

"A musician once told me there isn't another instrument like this one in the galaxy."

"But there are other instruments. You could choose from those of a thousand worlds. Surely one construction of wood and metal is not so different from another?"

To go to the stars, Kriss thought. To cross the great Dark, to breathe the air of alien worlds, to perhaps touch Mother Earth herself…

…to find a family…

Almost unconsciously, his arms loosened from the touchlyre. He looked up again at the stars, drank in their light with his eyes—and made up his mind. "Agreed."

Vorlick rubbed his hands together. "Excellent! Come to the spaceport gate at dawn. Bring the instrument." He turned and vanished into the darkness.

Kriss listened to his footsteps fade, then turned and walked slowly on toward his room. He climbed the familiar, rickety wooden stairs on the outside of the old brick building, past the dingy window through which shone a faint yellow light from the seamstress's lantern, unlocked his door and went in. Lighting his single candle, he looked around the tiny chamber. The ceiling with its small square skylight was simply the underside of the roof, and so low on one side he had to stoop to get to his bed, the only furniture aside from a rough-hewn table and rusty metal chair. I won't miss this, he thought. I won't miss anything on this planet.

But he didn't feel euphoric, as he had always expected to feel when he finally found a way to fulfill his dream. Instead he felt—numb? No, not numb—depressed.

Why? he asked himself. I'm going to the stars—all my dreams are coming true!

But the feeling persisted. As always when his spirits needed lifting, Kriss took out the touchlyre. Playing it was cathartic; he could lose himself in music as so many others on this impoverished planet did in wine.

He held the instrument in his lap for a moment, running his fingers over the sinuous curves of its velvety, unvarnished wood. Then he raised it and placed his hands on the copper plates.

The strings screamed: discordant, angry, ear-shattering. Kriss snatched his hands away. The touchlyre had never made a sound like that before! Had he broken it? He touched the plates again, cautiously, and again the instrument howled.

Disgusted, he tossed it on the table. If it was broken, he was well rid of it. He'd find himself another instrument, from one of those thousand worlds of which Vorlick had spoken. He undressed, blew out the candle and crawled into bed.

Just before sleep claimed him, he thought he heard the instrument's strings softly humming; but of course that was impossible, with no one touching the plates.

He dreamed. He was performing in Andru's, as he had done so many times, playing of his longing for the stars. That longing filled him with almost physical pain, but pain he could bear as long as he kept playing.

But suddenly the touchlyre disappeared, and he stood on an alien planet, strange and beautiful. Then another new world surrounded him, and another, and another, flashing past faster and faster, but no matter how exotic, how wonderful, they did not satisfy his longing, and the ache grew ever more acute.

And then he came to a world where dwelt a man who, he somehow knew, was his father's brother. His uncle rose to greet him, laughing, and hugged him, welcoming him to his family…

…but still the longing burned within Kriss, stronger than ever, so strong he suddenly knew it could never be quenched, and he broke away and screamed and screamed and—

—woke, gasping, bathed in sweat, his blanket a tangled heap on the floor and the scream echoing in his ears. His scream—or—he glanced sharply at the touchlyre, barely visible in the faint illumination from the skylight. It seemed to him he could hear the strings vibrating down to stillness, as though a mighty chord had just been wrung from them.

Nonsense, he told himself. He retrieved his blanket. No dreams troubled him the rest of the night.

In the morning he rose very early, put the touchlyre and the few clothes he owned into a backpack, and headed down the stairs and through a thin morning mist to the spaceport. The mountains towering above the city still hid the sun, but light filled the sky.

Vorlick waited at the spaceport gate. "Did you bring it?" he asked at once.

"Yes," Kriss said, startled by the blunt question.

"Take it out. I want to see it in the daylight."

Nonplused, Kriss did as he was told. But as he took the touchlyre from its case it hummed to life in his hands, and from it crashed a single explosive chord that echoed through the silent streets. Vorlick stumbled back as though slapped. "What—"

Kriss didn't hear him. The chord had sent the whole dream of the night before flashing through his mind, and it suddenly made perfect sense to him. His longing wasn't so much to see the stars, or even to find his family, but to find himself. He was doing that, bit by bit, through the touchlyre, journeying into his own soul to find out what kind of person he was, healing the wound made when he was orphaned on Farr's World.

Without the touchlyre, he could never finish that healing process. Wandering around the stars with the touchlyre lost to him forever would only hurt him worse; and even if he found a family, he would have lost something just as important.

Kriss's eyes suddenly focused on Vorlick. "No."

"No?"

"I've changed my mind. I'll keep the touchlyre. I'll find my own way into space." He started to turn away.

Vorlick reached into his pocket and pulled out something metallic and deadly looking. "Stand still," he said, his voice as cold as space. "That's not one of your options. You don't even know what you have, but I do. It's a working artifact from an ancient, alien civilization, uncovered by two archaeologists on a planet we may never find again. They fled here with it when they realized someone knew they had it and was out to get it." He smiled humorlessly. "Me, of course. It was almost fifteen standard years ago. I tracked them here, only to find they had died in an aircar crash. I assumed the artifact was destroyed with them.

"But then, just a few months ago, a spy on this world told me of a strange instrument in the hands of a boy—an instrument unlike any other.

"I did some checking. I found that the archaeologists had an infant son shortly after they arrived here, who was not in the aircar when it crashed—a baby who has become a young man—the minstrel with the unique instrument.

"So now, Kriss Lemarc, though I must withdraw my offer of placing you in a ship's crew, I give you your parents: Jon and Memory Lemarc, archaeologists. And I also give you knowledge of what your 'touchlyre' is: the only relic of an ancient alien culture, and worth a fortune you cannot imagine.

"In exchange for that information, you will now give me this instrument." Vorlick put his hand on it. "Or I will kill you."

Kriss tore the touchlyre away from him. "No!"

And from the strings that cry of defiance exploded again, with a force that surpassed sound. Kriss, paralyzed, felt all his violent emotions, fear, awe, defiance, hatred, pouring through his hands into the touchlyre, adding to the force it hurled at Vorlick like a weapon. The power coursed through Kriss like a cleansing tide—and he knew he couldn't stop it if he wanted to.

Vorlick's face paled and slackened and his eyes glazed, then closed. The gun dropped from his nerveless hand as his legs buckled, and he fell to his knees and then to the ground.

Finally it ended. Kriss felt, not empty of emotion, but as if he now had room to truly experience and understand his emotions for the first time, as though a gritty residue clogging his mind had been washed away.

He looked down at Vorlick and pitied him. The man lay unconscious, and Kriss knew he had nothing more to fear from him.

Then he raised the touchlyre, silent again, and held it at arm's length, studying it in the first rays of the sun, streaming through a cleft in the mountains behind him like searchlights. The orange beams made the wood and copper glow, reflecting the power hidden inside the ancient artifact. Just what that power was, and where it came from, he might never know: but he knew it was on his side.

He let his gaze travel to the tall starships beyond the gate, stark against the brightening sky. Above the tallest a single star still outshone the dawn light.

Someday, Kriss thought. Someday I'll make that journey.

That dream was still his: but now he knew the real journey lay within him. He turned his back on the spaceport and walked back to his attic room.

#

In a bar called Andru's, near the only spaceport of an obscure planet, starship crewmembers come to sit quietly and listen to a boy play a strange instrument of space-black wood and burnished copper.

His music sings of the infinite Dark and the suns that burn within it. It shimmers like starlight on alien seas, and whispers with the voices of strange winds.

March 3, 2012

Saturday Special from the Vaults: Follow a Song

Last Saturday I posted the opening to the first novel I wrote, when I was 14 years old. This week we jump ahead four or five years to when I was attending Harding University in Searcy, Arkansas (that's a photo of the library). This story, "Follow a Song," was a winner in the school's annual creative writing contest, which meant a lot to me at the time: maybe I actually could become a published writer some day!

Last Saturday I posted the opening to the first novel I wrote, when I was 14 years old. This week we jump ahead four or five years to when I was attending Harding University in Searcy, Arkansas (that's a photo of the library). This story, "Follow a Song," was a winner in the school's annual creative writing contest, which meant a lot to me at the time: maybe I actually could become a published writer some day!

The next year I was out of university and working at the Weyburn Review as a reporter/photographer, but it would be a while longer before I actually sold a short story.

Re-reading this for the first time in years, I'm not too horribly embarrassed by it. Although the snatches of poetry are heavily Tolkien-influenced, at least the first stanza of the first one!

Enjoy!

***

Follow a Song

By Eddie Willett

Telar, perched on the bottom branch of the dead tree, stared sheepishly down at his father, who glared up at him. "Telar," said Annuin with some heat, "I am a blacksmith, but I cannot make a living as one when I must leave my forge cold to search for you. Why are you not at the war-hall practicing your swordplay as you should be?"

Telar climbed down from the tree, but hung his head and said nothing, hearing exasperation in Annuin's voice as he continued, "It has been three months since the First Rite, boy. What's wrong with you? For two months you were the most promising firstling, when Master Nimarl was teaching you the history of the kingdom. Yet now he tells me you are spending more and more time away from your instruction—now, when you have left behind the dull classroom and gone on to the war-arts, your true study. Nimarl tells me you are far behind the others in swordplay, archery and spearwork. Yet when you should be practicing, I find you sitting in a tree, playing the harp and singing!" His voice rose almost to a shout.

Telar flushed. He fingered the carved and polished wood of his harp, and ran his fingers over the silver strings. The instrument breathed a faint chord. He dared to raise his head slightly, peering up at his father through his eyelashes.

Annuin's jaw clenched. "You are my youngest son, Telar. Your three brothers are all warriors; Kerpal is even now recovering from the honorable wounds he received defending the King at Sazaran. Where have I gone wrong with you?"

Telar looked down again. He loved his father, but it hurt to know Annuin considered him a failure. In his younger days Annuin had been a King's Guard, and could not understand why a healthy, strapping youth of Telar's years, bearing the scar across his chest of the coming-of-age ceremony known as the First Rite, would want to waste his time in reading and, worse, music.

But Telar detested all the trappings of war the firstlings were taught: the clashing swords, the bloodthirsty shouts, the weight of a shield, the awkwardness of a scabbard, the dust and sweat of the practice court. He hated—

He suddenly became aware of an expectant silence. He glanced up. "What did you say, father?"

"Go to your lessons, boy," Annuin said wearily, and turned away.

Telar watched him go, then looked at the sun and sighed. His father had found him too soon. There would be a lot of daylight for swordplay yet, and he didn't dare stay away now his father had come looking for him. Slinging his harp over his shoulder, he waded through the tall grass to the narrow path leading down to the village.

He could hear the crack of wooden swords and the cries of his fellow firstlings as he approached the gate of the War Hall, but silence fell as he entered the courtyard. Every face turned toward him, then looked expectantly at Master Nimarl, a burly, middle-aged man, just beginning to turn gray, who pushed through the boys until he stood glaring down at Telar. "Well?"

"I'm sorry, master—"

"Sorry? You're not sorry. Twice before you have been so late you missed sword practice altogether. You have also missed spearwork three times and archery at least once."

The other firstlings snickered, and Telar looked at the ground. "Yes, master."

"You must be punished, Telar."

Telar's head jerked up. "Punished?" The only punishment until now had been the lectures on the importance of the war-arts that Nimarl would deliver to anyone at the slightest provocation.

"Unless you can demonstrate that your skills in the war-arts are such you can afford to miss practices."

"But, master, I'm the best reader, I spend more time than is required on geography, history, calculating—"

"Enough!" Nimarl roared. "Such things are important only in better suiting you for battle. Without the war-arts, they are meaningless, suited only to women and old men!"

Telar's face grew hot. "Meaningless? They're our noblest achievements!"

The courtyard rang with Nimarl's scornful laughter. "Women's words! Here, boy." He tossed a javelin to Telar. "Now we'll find out how much of a man you are!"

The rest of the afternoon was a nightmare. Telar's javelin missed the target by the width of a doorway, and in spear-and-shield sparring he received, almost at once, a blow to the stomach that doubled him over, gasping. "What good is reading now, boy?" Nimarl taunted him.

In archery he fared little better. Though he hit the target, his arrow was so near the edge the wood splintered and the shaft fell to the ground.

Then came swordplay. His first bout was with one-handed swords and shields; he lasted no more than ten seconds before his opponent's wooden blade cracked him on the wrist so hard he dropped his weapon. Then came two-handed swords; almost before he could blink something smashed across his head and he found himself flat on his back in the dirt, looking up into the sneering face of the other boy.

Telar sat up, gingerly feeling the bump on his head, then got a little shakily to his feet and faced Nimarl. "All right!" he said defiantly. "You've proved I'm a poor fighter, master. How will you punish me?"

Nimarl looked from him to the contemptuous faces of his fellow firstlings, and shrugged. "I think your punishment is already sufficient." He turned his back and clapped his hands. "Enough standing around, lads!"

Telar heard the taunts thrown at him as the firstlings returned to their own weapons and realized what Nimarl had done. Furiously he snatched up his harp and left the courtyard.

He climbed back up to the tree where his father had found him and slammed his fist against it, then leaned his forehead against its rough bark and kicked at the ground with his foot. No doubt his father had known Nimarl intended to make a fool of him, and had approved it as suitable "punishment." That made him even angrier. He knew his father didn't think very highly of him, but to agree to his humiliation . . .

But he was just as angry with himself. What was wrong with him? Why didn't he like the war-arts? He was sure he was the only firstling the village had ever produced that was not dying to go into battle.

He turned his back on the tree, unslung his harp, and slammed his fingers across the strings, crashing through a raw, sorrowful tune and ending with a harsh discord that summed up his feelings very accurately.

A voice behind him said, "A poor note on which to end a performance, don't you think? It might spoil your host's appetite, and that could easily spoil your own."

Telar spun to see a tall, broad-shouldered man with graying hair and beard. He wore a longsword on the belt of his blue tunic, but he also carried a harp, and Telar's eyes went to it immediately. "Your pardon, my lord—"

The man laughed. "Kailar is my name, and my only title. I come from a fishing family; hardly noble heritage. Now, however, I am a bard, as you seem to be yourself. I see there is no great house at which to play in this village, so if you could direct me to the inn—unless, of course, you already have the only business here, in which case I shall certainly leave it to you and move on."

"I am not a bard, my lord."

"Kailar. What are you, then?"

Telar grimaced. "Only a firstling, and a poor one. As for our inn, unless you sing of war, you won't find much welcome there."

Kailar shrugged. "I can sing songs of war if of war I must sing." He looked at Telar thoughtfully. "You deny you are a bard, but I heard you playing as I came up—and playing well, though, in truth, the tune was not much to my liking."

"Nor mine. But little is. The things I want to learn are despised by my teachers. Most of our time is spent in the 'glorious' pursuit of learning to kill."

Kailar raised an eyebrow. "Traditional firstling instruction disagrees with you?"

"I hate it!" Telar burst out, and, instinctively feeling Kailar would understand, poured out the story of his embarrassment that afternoon. "History—geography—the things that matter, he dismissed as meaningless! You're a bard, Kailar, a learned man—is what I feel wrong?"

Kailar said nothing for a moment, looking down at the town. "I think I will come to your house, Telar," he said finally. "You said your father was in the Guard—he will surely welcome me for my news, if not for my music. Then tomorrow I will try to help you with your problem."

Joyfully Telar agreed and started down the hill at a gallop. "Come on!" he called over his shoulder. "It's almost suppertime!"

Kailar followed more slowly, smiling.

Annuin was more than a little surprised when Telar arrived with a guest, but made Kailar welcome as the custom of hospitality demanded. "Your name, my lord?" he said, taking the bard's cloak.

"Kailar, son of Gerra, originally of Rhys." Kailar took off his sword and leaned it against the wall by the front door. "My father was a fisherman, but I am a bard—and in your debt."

Annuin laughed. "A bard. I might have known. Well, you are welcome, Kailar. Take a place at our table." As Kailar bowed and sat down, Annuin turned to his son. "And you, firstling. Did you go to your practice as I commanded?"

"Yes. And what you knew would happen, happened," Telar said sullenly.

"What?"

"You knew Nimarl planned to humiliate me in front of the other firstlings!" Telar burst out. "You must have! You probably arranged for it. But it won't work, father! I will not learn the war-arts. I'll—I'll go with Kailar, and be a bard!" The last was a flash of inspiration.

His father's face reddened. "You will hold your tongue, Telar," he growled. "I will not have you being disrespectful to me before a guest—a bard, at that! Would you shame me before the entire country? Sit at table!"

Telar banged down on the bench beside Kailar, shooting a glance at the man he had just allied himself with. But Kailar seemed oblivious. His eyes were closed, and his lips moved silently.

Thus he remained until Telar's mother, Hella, brought in the meal. She retired at once to the kitchen to eat her portion; it would not have been seemly for her to dine at table with a strange man. As his plate was set before him Kailar opened his eyes, smiled at Hella, and reached for his spoon. "What were you doing?" Telar asked.

"Working on a new song," Kailar replied. "Part of it will be finished tomorrow."

"Will you sing it for me?"

"Perhaps. If all goes as it should." He would say no more about it. Instead he began talking to Annuin, and soon the two men were deep in discussion of the latest news of the King and his court. Telar marveled at Kailar's memory—he seemed to know everyone in the kingdom by name and everything they had done for the past ten years.

When the meal was over they settled in chairs around the fire, and Hella rejoined them. Then Kailar sang for them, mostly the great old songs of the ancient heroes and the world as it had been before the Scattering. Telar admired the bard's skill, but the songs were war-songs. He stirred impatiently.

Perhaps Kailar noticed; abruptly his playing changed to a minor key, and his voice filled with longing:

Tree and leaf and wood and plain,

Snow and wind and sun and rain;

Day by day they come and go

And pass forever by.

Deeds of peace and deeds of war,

King and warrior, rich and poor;

One by one they rise and fall,

And pass forever by.

Day to night and night to day

I go my ever-restless way

No home, no hearth, no kith, no kin—

They've passed forever by.

Infant, child, youth and man;

The months and years like seconds ran—

My life, my songs—like winter wind

They pass forever by.

But flowers blossom, rivers run;

Each day beneath the springtime sun

New life, new hope, new joy appears

That never will pass by.

And so I play, and so I sing,

To bring my wintry soul its spring—

And new souls, too—my legacy

To pass forever—on."

For a moment after the last chord died away only the crackling of the fire on the hearth broke the silence. Then Annuin stirred and said gruffly, "You've travelled far today and must be tired. Telar will show you to your room."

Kailar rose and bowed. "I thank you, sir and lady. May you sleep well." Taking up his pack, Telar led him to the room they would share. He offered the bard his bed, but Kailar laughed and said he was as used to sleeping on the ground as on a mattress. He took blankets from his pack and spread them on the wooden floor.

Telar sat on the bed and watched him. "Kailar . . . " he said finally.

The bard glanced at him. "Yes?"

"That last song—it's—I—I would like to learn it," he finished lamely.

"It touched you, then? I thought it would. I wrote it a year or so ago, after—well, after a painful time. Certainly I will teach it to you—if you will return the favor and teach me some of the songs you know."

"I know nothing you would want to hear!"

"But you do, lad, you do. We each learn songs in our day-to-day lives that no one else knows. I try to share mine; won't you return the favor?"

"I have written one or two," Telar admitted shyly. "If you really want to hear them—"

"I would. But," he continued, lying down on his blankets, "I think it should wait until tomorrow. I 've walked my legs to the bone today, and you should rest as well. Tomorrow I will come with you to the War Hall."

Telar looked down. "I—I almost wish you wouldn't."

"Why not?"

"I—well, I know what Nimarl and the others think of me for not wanting to be a warrior. I don't want them to think that of you."

"But, Telar, that's exactly why I'm going—to show them, if I can, that to be a bard and not a warrior does not make a man any less a man."

"They won't listen."

"Perhaps they will, if I use the right language. Now will you please go to bed and douse the candles so we can both sleep?"

Telar said nothing more, but though he undressed and lay beneath the blankets, it was a long time before he slept.

The next day dawned clear and cold; autumn was giving way to winter. Telar dreaded what was to come; he doubted he would be allowed near the library after slipping off the day before. He would have to spend the whole day at the war-arts. Nimarl might never let him read again.

"And I have read only half of the Book of the Great, up to the passage where Shirra meets Gharus on Mount Nyngal to decide in single combat the fate of the kingdom," he told Kailar at breakfast.

Kailar looked at him with the amused expression Telar was beginning to find familiar. "The Book of the Great? Isn't that a rather war-filled book for someone who hates the thought of war as much as you do?"

"It's different in legends," Telar said defensively. "It means something. Here-and-now, all it is is killing other people. Can that ever be right?"

Kailar chewed and swallowed thoughtfully, then said, "Do you see nothing noble in war, then?"

"Nothing!"

"Nothing? Is it not noble for a man to give his life to save another's? Or to give it to save his family—or even the lives of an entire race? Is there nothing noble in such acts of heroism?"

Telar frowned. "Well—perhaps there can be noble acts in war. But war itself is evil!"

Kailar shrugged. "There are many evil things in the world, Telar. We try to avoid them, but we don't always succeed." Then he grinned. "Come, enough philosophy for early morning. Eat, then lead me to your War Hall. I am anxious to meet your teacher."

Telar finished his bread and cheese in thoughtful silence. Kailar had a way of making people examine their assumptions more closely than they were used to. Telar found it a not-entirely comfortable experience.

The War Hall courtyard, full of laughing firstlings strapping on practice armor and swords, fell silent when Telar entered with Kailar. Nimarl came forward to greet them. "Telar, you're late again—" he rumbled.

Kailar interrupted. "It's more my fault than his, Master Nimarl." He bowed. "I am Kailar, a wandering bard. I have accompanied my friend Telar to watch your instruction of firstlings."

Nimarl laughed. "I might have known our little harp-plucker would bring us a bard. Well, sir, you are welcome. But since you have given up the manly art of war, I don't know that you will find much here to interest you."

Kailar raised an eyebrow. "You consider barding unmanly?"

"Nay, sir! It is as manly as any occupation can be for someone who can no longer be a warrior. No doubt you were wounded or weakened by illness—I'm sure you were a mighty warrior in your youth."

Telar winced. He knew what was coming.

Kailar gave Nimarl an innocent look. "Master Nimarl, I have never been a warrior—only a bard, since my First Rite, trained in it by the great Theros of Gharwen."

Nimarl snorted. "Then I'm quite certain there is no point in your remaining here. We do not waste our time on such matters. Since you have no knowledge of the war-arts—"

"I didn't say that, Master Nimarl. I said I was trained as a bard."

"Sir, a bard is not a warrior."

"I bear a sword."

"Even Telar can bear a sword—though he has been known to trip on it!" Telar flushed. "But only a man can wield one—and all true men do!"

Telar's stomach lurched. He expected Kailar to leave in anger, but instead the bard astonished him by quoting a section of a song Telar knew: "The minds of men do differ ever; what's dull to one, to another's clever." Then he said, "I propose a wager, Master Nimarl. I wager I can defeat your best warrior—yourself, no doubt—in archery, spearwork and swordplay, just as Telar was tested yesterday."

Nimarl laughed. "And what would you risk on such a hopeless contest?"

"Name my stake yourself."

The firstling master considered. "Very well, then! If I win, you will proclaim to the firstlings that I am right, and you are no true man. Then you will spend the winter here, and amuse us at meals. If you win—"

Kailar raised his hand. "Nay, Master Nimarl, this part of the wager is mine. If I win, you will release Telar from his firstling instruction, and send his father a recommendation, as is your right, that he be apprenticed to me."

Excitement filled Telar. He straightened his shoulders. "There's nothing I would like more, Kailar!"

Nimarl shook his head. "You set a small stake. It would be little loss to me or the village were Telar gone. But, so, the wager is set. Shall we begin?"

"By all means," said Kailar.

A few moments later the firstlings clustered around the two men, armed with bows and quivers, at one end of the courtyard. At the other stood the target, a man-shaped cut-out of wood with a circle marking the heart. At the center of the circle was a round spot the diameter of a gold piece.

Nimarl loosed his arrow first. The bolt slammed into the heart, and the nearest boy ran to look. "Two finger's breadths from the center!"¯he shouted, and the firstlings cheered.

Nimarl turned to Kailar smugly. "Your shot, sir bard."

Kailar made no reply, but put arrow to string, drew and released in one smooth motion. The dart shuddered into the wood an inch and a half from Nimarl's arrow—precisely in the center of the heart.

The firstlings gaped at each other. Nimarl flushed, then bowed stiffly to Kailar. "Well shot. Spearwork is next."

The spear-throw went as had the archery contest. Kailar's spear hung in the center; Nimarl's was a good hand's breadth away. A sound suspiciously like muffled laughter ran through the gathered firstlings, but it died in a hurry when Nimarl glared around at the boys. The master did not congratulate Kailar this time, but said only, "Spear-and-shield is next, bard."

The two men took blunted wooden staffs and round wooden shields and faced off. The contest was brief, wicked, and decisive. Almost before the firstlings knew what had happened, Nimarl was down, doubled over by a blow from the blunt tip of Kailar's shaft. This time the laughter wasn't muted at all.

Nimarl said nothing to the bard, but stalked into the War Hall. When he returned, he carried not the wooden swords and shields used by the firstlings, but the razor-sharp and deadly war-weapons that hung in the hall. He flung shield and sword before Kailar, and Telar paled. He had never seen Nimarl so angry—he had never seen anyone that angry.

"Bard," Nimarl said between clenched teeth, "you are not a bard at all. You are obviously a warrior—a warrior brought into this court by Telar to humiliate me before the firstlings. But no more! I Challenge you!"

The firstlings gasped. Those words meant a duel—probably to the death. Telar looked at Kailar's white face and realized he had not anticipated this. "Master Nimarl," he protested, "this is not what I sought! Believe me, I am not here to shame you, but only to show you that there are true men who are not warriors. Don't make me fight you."

"I have Challenged you!" Nimarl shouted. "You must fight—or I will kill you where you stand!"

The color flooded back into Kailar's face; he stiffened. "As you wish," he said coldly.

"In the King's name, Kailar—" Telar burst out.

The bard turned to him. "Did I not tell you sometimes evil cannot be avoided? But wait and see—some good may yet come of it." He turned back to Nimarl. "I am ready."

Nimarl pointed at the weapons in the dirt before him. "Arm yourself!"

Kailar hefted the sword and shield for a moment, then saluted Nimarl with his blade. Nimarl did not salute: he attacked.

His first stroke, blocked by Kailar's shield, drove the bard almost to his knees. Telar cried out, certain Kailar would fall. But he did not. Instead he threw his shield to one side, knocking Nimarl's sword-arm away, and drove in with the point of his blade¯– but not at Nimarl's vitals. Telar, with a thrill of fear, realized Kailar fought not to kill, but only to disable—to end the contest with no loss of life.

Nimarl realized it as well, and as he blocked the thrust with savage glee, cried, "Do you show me mercy, bard-who-is-no-bard? I'll have none for you!" A slash of his sword came within a hair's breadth of cutting Kailar in two, but the bard sprang back. With his own sword he blocked the return stroke, and smashed his shield down on Nimarl's with such force the master dropped to one knee. Nimarl tried to thrust up, under Kailar's shield, but Kailar brought the shield's edge down on the blade and it flew from Nimarl's grasp.

A cry rose from the watching firstlings. Nimarl was doomed!

The firstling master paled. He raised his shield in a hopeless attempt to block his death blow.

But it did not fall. Kailar stepped back. "Noble Nimarl," he panted, "I declare myself victor in the Challenge, but I decline blood-right."

Nimarl lowered his shield in amazement. "But you disarmed me—I insulted you—are you not going to take revenge?"

Kailar shook his head. "Master Nimarl, I sing songs. Someday I will sing one about today, and revenge does not make a sweet song."

Nimarl stared at him, bewildered, sweat streaking the dust on his face.

Telar ran to Kailar's side. "Kailar, are you all right?

Kailar laughed, a little shakily. "Not a scratch."

"And did you mean what you said? About making me your apprentice?"

The bard looked down at him. "There is a condition."

"Anything!"

"I will teach you the war-arts."

Telar stepped back a pace. "But—but—"

"Did you think I did all this—" he tossed his sword and shield into the dust—"only for these?" He gestured at the silent, watching firstlings. "Didn't you learn anything? It's possible to be both strong and peaceable. Sometimes you have to be strong and willing to fight in order to remain peaceable. But the rest of you—" he raised his voice then, and turned slowly, looking from face to face. "Know there is more to life than war! I take no joy in what I have done." He held out his hand, and hesitantly, Nimarl took it and let the bard help him to his feet. "None at all," Kailar finished in a low voice.

"I—I don't understand," said Telar.

"Well, never mind. There'll be a long time to explain it." He kept his eyes on Nimarl. "Right?"

Nimarl inclined his head a fraction of an inch. "I do not understand you, bard; nor do I understand Telar. But I am no longer shamed. Bard or warrior, I would we had had a hundred like you in the Guard! I will tell Annuin you would be a worthy master for his son."

"Thank you, master Nimarl." Kailar bowed, then looked at Telar. "Shall we go, apprentice?"

"With pleasure, master—if."

"If?"

"If you will tell me what the song is you said would be partially finished today." Telar planted his feet. "That is my condition."

Kailar laughed. "Why, that's your song, Telar. The one you write day to day. You've just finished a major part of it. Now you get to move on to a whole new verse."

Telar frowned. "I'll never understand you, master."

Kailar led the way to the courtyard gate. "Perhaps someday, lad. Perhaps someday." And as they walked back to Telar's home, he sang:

And so I play, and so I sing,

To bring my wintry soul its spring—

And new souls, too—my legacy

To pass forever—on.

March 2, 2012

Days of future past

Sometimes people ask me why I like to write about science. There's all sorts of fancy-schmancy reasons I could come up with about the importance of science to modern society and the wonders of the natural world and the joys of intellectual stimulation—but the truth is, I write about science because I grew up reading science fiction.

Sometimes people ask me why I like to write about science. There's all sorts of fancy-schmancy reasons I could come up with about the importance of science to modern society and the wonders of the natural world and the joys of intellectual stimulation—but the truth is, I write about science because I grew up reading science fiction.

And you know what? That would have warmed the cockles of Hugo Gernsback's heart.

What's that? You never heard of Hugo Gernsback? Well, you're about to!

Modern science fiction stands primarily on the shoulders of two writers: France's Jules Verne and England's H. G. Wells. Verne played on the public's interest in burgeoning technological and scientific advances as the 19th century advanced, and told stories of fantastic journeys to the moon, beneath the seas, to the center of the Earth, and even Around the World in 80 Days.

Wells focused less on the future of technology than on the future of society. The Time Machine was a parable concerning future relations between the working and ruling classes. And The War of the Worlds, the first alien invasion tale, was more about the insignificance of humanity in an uncaring universe than the likelihood of life on Mars.

Yet neither Wells nor Verne is considered "the father of science fiction." That title belongs to Hugo Gernsback.

Gernsback wasn't a writer, at least not to start with. Rather, he was a pioneer in the fields of electricity, radio and television. He sold America's first home radio kit in 1904 ($7.50 at Macy's). When government regulation of radio put him out of business, he repackaged the left-over parts as kids' electronics kits. He also founded New York radio station WRNY, where some of the world's first regular TV broadcasts began in 1928.

But he also moved into publishing. In 1908 he founded the world's first radio magazine, Modern Electrics. For a 1911 issue, finding himself short of material, he filled a few empty pages with a piece of fiction, entitled "Ralph 124C 41+: A Romance of the Year 2660." The story was so popular he wrote more, even publishing them as a novel in 1925. As a prose stylist, Gernsback left a lot to be desired ("Bang! Bang! Bang! Three shots rang out! Each more horrible than the last!") But he wasn't worried about style. He used his stories to toss off scientific predictions like one of his electrical devices might toss off sparks.

Microfiche, skywriting, solar power, holograms, fax machines, aluminum foil and a "parabolic wave reflector" (radar) were all part of Ralph's daily life—but certainly not yet part of the daily lives of Gernsback's readers.

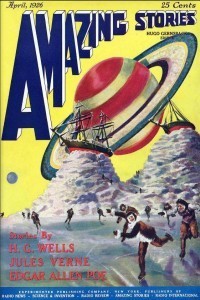

Based on Ralph's success, Gernsback founded a new magazine: Amazing Stories. The first issue from April 1926 (which you can read online, along with many other old magazines, at pulpmags.org) featured old stories by Verne and Wells and Edgar Allen Poe, but was nevertheless, Gernsback claimed in his introduction, "entirely new—entirely different" from other fiction magazines, because it would be devoted to what he called "scientifiction."

He defined scientifiction as "a charming romance intermingled with scientific fact and prophetic vision." His rationale for the new magazine could have been written yesterday: "It must be remembered that we live in an entirely new world. Two hundred years ago, stories of this kind were not possible. Science, through its various branches of mechanics, electricity, astronomy, etc., enters so intimately into all our lives today, and we are so much immersed in this science, that we have become rather prone to take new inventions and discoveries for granted. Our entire mode of living has changed with the present progress, and it is little wonder, therefore, that many fantastic situations—impossible 100 years ago—are brought about today."

Gernsback saw the new genre as a way of "imparting knowledge, and even inspiration, without once making us aware that we are being taught," and that's exactly how it worked out: many of the children who read Amazing Stories under the covers went on to become scientists, engineers or science fiction writers themselves. Gernsback, as Ray Bradbury put it, "made us fall in love with the future."

Implicit in science fiction is the realization that the future will not be like today, and in both its "Vernesian" (focused on the science and technology) and "Wellsian" (focused on the effects of science and technology on society) strains, prepares us and excites us for—and sometimes alarms and warns us about—what that future may hold.

Hugo Gernsback died in 1967, not quite living long enough to see humans walk on the moon. Science has honored him by naming a lunar crater after him. Science fiction, meanwhile, hands out awards every year for the best new work in the field.

They're called Hugos.

(The image:the cover of Amazing Stories , Volume 1, Number 1, April 1926.)

February 25, 2012

Saturday Special from the Vaults: The opening to the first novel I wrote as a teenager

I've worked with young writers quite a bit over the past few years, teaching the Sage Hill Teen Writing Experience for three summers in a row, serving as writer-in-residence at Riffel High School and now, of course, as writer-in-residence at the Regina Public Library. I've also edited the Saskatchewan Writer Guild's magazine for young writer, Windscript, and was involved in an on-line mentoring program for young writers for a couple of years.

One reason I like working with teen writers is because I used to be one. I wrote my first short story at age 11 ("Kastra Glazz, Hypership Test Pilot"), wrote a fairly long piece called The Pirate Dilemma in Grade 9, when I was 13–and then, in my Grade 10 year, when I was 14, wrote my first novel, The Golden Sword, later revised into The Silver Sword when I realized a sword of gold was a little too heavy to be practical.

(Although, as you can see from the picture, another author, Janet Morris, stuck with that title. Though I guess I had it first, since I wrote this in 1973-74 and her book came out in 1977. It's an...interesting…cover, isn't it?)

(Although, as you can see from the picture, another author, Janet Morris, stuck with that title. Though I guess I had it first, since I wrote this in 1973-74 and her book came out in 1977. It's an...interesting…cover, isn't it?)

So here is what I wrote when I was 14. If you're a teen writer, you may want to compare, just to see what someone who eventually became published was turning out at your age. If you're an older writer, you may find it amusing. And if you've ever been confused by the term "info-dump," then I think you'll find a striking example of it in the first few paragraphs!

I'll probably post more of this as time passes (and also some of my other two high school novels, Ship from the Unknown and Slavers of Thok, but this is all I've typed in so far.

Feel free to cringe. I know I do! :)

***

THE GOLDEN SWORD

By Eddie Willett

The sun rose slowly over the misted hills of Solonia, casting long shadows across the road, sending an eerie twilight creeping slowly back from the high cliffs on the opposite side of the valley of the Prall. Far below the road, at the bottom of a deep gorge, the Prall river flowed swiftly toward Lagon, far in the north.

Lagon was the arch-enemy of Solonia. Solonia, trading with the barbarian city-states, had encroached on territories in the Desert of Coran that Lagon considered its own. Negotiations slowed—broke down—stopped Soon after that Lagon had declared war on Solonia. That was the First Lagonian War.

When both countries had devastated each other and neither one would surrender, the war ground to a halt. But nearly a hundred years later, Lagon, fully replenished, had determined to take over the barbarian countries between Solonia and Lagon. Solonia had been sworn to defend the barbarians, and thus had begun the Second Lagonian War.

And now Kyle, Master Soldier of the Solonian Empire Militia, was returning as the advance messenger of the Militia, bearing news of Solonia's victory over Lagon.

Things had changed in Solonia. The capital city of Solonis had been fortified and special troops of the Militia had been stationed in Solonis to protect it. And the city had grown immensely as refugees from the attacked parts of Solonia had poured into it.

Now the sun had climbed to such a height that the Prall River glinted like quicksilver far below him and the mists were evaporating in the heat. As they cleared, he spotted the walls of the city in the distance. He glimpsed the glint of the Gate-Guards' armor and weapons as they circled the city's mighty walls.

Kyle rode on in silence, reflecting on the events of the past three months. He felt in his belt-pouch. Yes, the citation was still there. It read:

TO MASTER SOLIDER KYLE OF THE SOLONIAN EMPIRE MILITIA:

A CITATION FOR HONOR AND REWARD TO KYLE, FOR BRAVERY ABOVE AND BEYOND THE CALL OF DUTY AS WELL AS WITHIN IT.

It was addressed to King Lodi of the Solonian Empire, from the Commander-in-Chief of the Militia. But before he presented it to the king, he had duty to perform. Any moment now the Gate-Guards would surely glimpse his brilliant metal armor and gleaming white mount. They would then send out an honor guard to greet him as they had done on his previous message-carrying visit.

But as he drew nearer to the city, he began to wonder what was going on. By now there was no doubt but what they had spotted him–unless they were asleep or dead–but where was the honor guard?

He racked his brains for some reason behind this failure to honor an officer properly–and found it. From sunrise to midnight on the fourteenth day of the second month of summer all rewards were presented to those that deserved them–those that had performed some feet of greatness in the past year. Everyone's record was checked, and the names announced and the deeds recorded of those people who deserved a reward. Then, in the Reward Ceremony that night after the evening meal, they were presented with the proper rewards All citizens except the Gate-Guards would be in the Central Square–so no honor guard.

The sun rose higher, and finally the full blaze of it reached the road and set the city shimmering in the heat.

Kyle spurred his horse into a gallop and raced for the city in a cloud of dust. As he neared the gates he saw a flurry of activity and heard shouting, indistinct above the thunder of his horse's hooves, but sounding like the word Kyle. He had been recognized.

The gates swung open and he shot through them into the city, reining his horse to a sudden stop. The chief gatekeeper looked down at him. "Any news, Master Kyle?"

"Yes–great news. I'm going to the Central Square. The criers will be spreading the news soon."

He trotted his horse on through the streets toward the Square. As he neared it the people flooded out to meet him. "What news do you bring of the war?" "Are we winning, Kyle?"

"Hold on just a moment and I'll tell you." The mob quieted, and Kyle lapsed into formal ceremony. Resplendent in armor and black battle tunic, he stood up in his stirrups and took out a small golden horn. This he blew to announce the message. Kyle filled his lungs and shouted, "A message from Lagon!" He paused, and the crowd held its breath. "We have won! The war is ended–and we have obtained the victory!"

The crowd erupted in a flood of cheering and yelling. "We won! The War is over!" So loud was their jubilant yelling that no one heard Kyle's call for the king. Indeed, nothing could be heard over the cheering, singing mob. Kyle raised the golden horn and blew as loud as he could. The mellow sounds died away and with them the sound of the crowd. "More news, Master Kyle?"

"No, but I request an audience with the king."

"The king! Call King Lodi! Master Kyle requests an audience with the king!" Kyle heard the request fling itself through the crowd and toward the Castle. Then there was an expectant silence until a reply hurled itself back through the packed multitudes. "Master Kyle! the king will accept your presence at once!"

Hearing this, he reined the horse around and thundered up the street to the Castle. He stopped before the massive gates and called to the Royal Gate Guards, "Master Soldier Kyle here for an audience with the King."

"Enter, Master Kyle." The huge ironwood-and-steel gates swung open and Kyle trotted through. He stopped and dismounted, and as the groom took his charger, marched to the throne room doors. He presented a magnificent figure in the bright sunshine–6 feet, 4 inches tall, young, strong, handsome, muscular, resplendent in armor, carrying glittering spear and shining sword.

The doors were opened and a valet appeared to take his weapons. He gave them to the boy and entered the next room. For a moment he was blinded from the sudden transition from light to darkness. The only light in the small room came from the smoking torches in the bare stone walls.

But as Kyle's eyes grew accustomed to the dimness he glimpsed the rough wooden door in front of him. Knowing the correct procedure from the many times they had drilled it into him during training, he called out, "Master Soldier Kyle humbly requests an audience with his Majesty Lodi, King of the Solonian Empire."

"Enter, Master Kyle," came the reply from within. Kyle opened the door and entered the Throne Room. Now he was again momentarily blinded, this time by the light streaming in through the huge glass windows, the largest glass windows in Solonia. This light, once used to, showed the magnificent splendor of the Throne Room.

Four walls of the hexagonal room were covered with beautiful silver, black and gold tapestries depicting the First Lagonian War, the coronation of Lodi, the fortifying of the city, and an unfinished one of the Second Lagonian War. The other four walls were almost completely glass.

In the center of the black and gold mosaic floor rested, like some rare and exotic jewel, the Royal Throne of Solonia. It was 7 1/2 feet high, and had been designed to represent all parts of Solonia. The silver and gold had come from the mines along the northern part of the Prall. The jewels had come from the Slater Mountains in the East. The black leather had come from the Western ranches, and the basic design from the city itself. It had been built by the Royal Metalsmith and Craftsman, Tolin.

But for who was all this splendor? At first glance the king would seem to the huge, bronzed, muscular giant standing beside the throne. But King Lodi was neither tall nor muscular. He was a short, rather old man, barely 5 1/2 feet tall, with snow-white hair and beard.

And yet, he was impressive. His eyes flashed fire, and he held his finely chiseled features proudly and high.

Kyle took all this in at a glance. Then he kneeled slowly until Lodi said, "Rise, Master Kyle." Kyle rose. "What brings you here do the Castle, Master Kyle?"

"I came for a twofold purpose. I came to bring news of our victory over Lagon–I suppose you have already heard this?"

"True. And the other purpose?"

"To present to you a citation sent from the Commander-in-Chief of the Solonian Empire Militia. If I may present it to you now–?"

"You may." Lodi snapped his fingers, and the giant strode forward, hand outstretched. Kyle opened the belt-pouch and removed the citation from it. He handed it to the giant, who in turn handed it to Lodi. "Thank you, Ronan." He opened the seal and unrolled the thin parchment. He read it, then looked up. "This citation is accepted. As today is the day of the Reward Ceremony, you will take this to the priest reading off the names of those deserving a reward. I will seal it." Again he snapped his fingers. Ronan lifted a door hidden in the tapestry. He returned with a golden seal, and the king stamped it into the parchment, where it left a clear print. Then Ronan returned it to Kyle. "Master Soldier Kyle, may the gods of sun and rain smile upon you and may you die a brave death."

"Thank you, your majesty."

"You are dismissed."

Kyle bowed, turned, and left the Throne Room. He passed through the dim entry room, and into the plush foyer. The valet reappeared, handed Kyle his weapons, and disappeared as quietly as he had appeared. The groom trotted out his horse, and Kyle mounted and rode through the Castle Gates back into the city.

February 24, 2012

Segmented sleep

It's happened to all of us at one time or another: we wake up in the middle of the night, have trouble going back to sleep, start worrying about the fact we're having trouble going back to sleep, start worrying about the fact we're worrying about the fact we're having trouble going back to sleep…and then the alarm goes off and we spend the rest of the day yawning.

It's happened to all of us at one time or another: we wake up in the middle of the night, have trouble going back to sleep, start worrying about the fact we're having trouble going back to sleep, start worrying about the fact we're worrying about the fact we're having trouble going back to sleep…and then the alarm goes off and we spend the rest of the day yawning.

Well, a February 22 news article by Stephanie Hegarty of the BBC World Service claims that both science and history suggest we should quit worrying and embrace our midnight wakefulness: that in fact, sleeping without waking for eight hours is an unnatural artifact of technological advances and something our ancestors would have thought extremely peculiar.

On the science side, Hegarty notes, about 20 years ago psychiatrist Thomas Wehr conducted an experiment that involved keeping a group of people in darkness 14 hours a day for a month. Not surprisingly, this disrupted their sleep: but by the fourth week, they'd settled into a new, stable pattern—not eight hours of uninterrupted sleep, but a four-hour sleep, an hour or two of wakefulness, and then another four-hour sleep.

On the historical side, there's the research of Roger Ekirch of Virginia Tech university, who in a 2001 paper and a 2005 book (At Day's Close: Night in Times Past), discusses the more than 500 references he discovered, in everything from diaries to court records to medical books to Homer's Odyssey, to a segmented sleeping pattern: a "first sleep" beginning about two hours after dusk, a waking period of an hour or two, and then a "second sleep"—exactly what Wehr observed in his subjects.

The references seem to indicate that this kind of sleeping was the norm.

Some people would get up and have a smoke or even visit neighbors during that waking period. Others would stay in bed, reading, writing or praying. (Prayer manuals from the late 1400s offer special prayers for the hours between sleeps.)

But Ekirch found fewer and fewer of these references going forward, until by the 1920s the notion of a first and second sleep seems to have disappeared.

He attributes that to improvements in domestic and street lighting. Better lighting at home made it more attractive to stay up late; street lighting made it more attractive to be out and about in the city. Businesses naturally took advantage of the change: coffee houses began to be open all night. There were simply more thing to do at night, and so the two-sleep pattern condensed into a single sleep.

As Hegarty puts it, "Night became fashionable and spending hours lying in bed was considered a waste of time."

That sense of wasting time and losing efficiency became more pronounced as the industrial revolution took hold. Today of course, there are a million things to do no matter what the hour of the day or night…and millions of us are sleep-deprived as a result.

If sleeping the night through in one unbroken stretch is not entirely natural for humans, it could explain "sleep maintenance insomnia," a condition where people wake up in the middle of the night and then have trouble getting back to sleep—and a condition that only shows up in scientific literature at the end of the 19th century, just as the concept of segmented sleep was beginning to disappear.

Hegerty quotes sleep psychologist Gregg Jacobs as saying, "For most of evolution we slept a certain way. Waking up during the night is part of normal human physiology." He suggests the segmented sleep pattern we used to enjoy may have played an important role in regulating stress, since that hour or two in the night was spent in rest and relaxation.

So the next time you're lying awake in bed in the middle of the night, don't think of it as insomnia. Think of it as getting back to your roots.

If segmented sleep was good enough for your great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandpappy, it ought to be good enough for you, too! And he didn't even have the option of browsing the Internet at 3 a.m.

Poor guy.

February 18, 2012

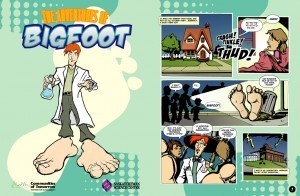

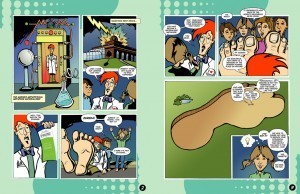

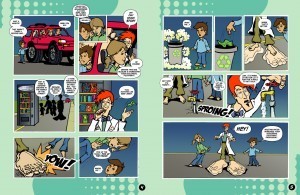

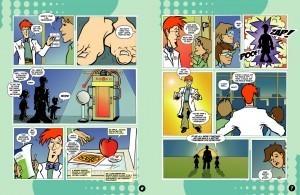

Saturday Special from the Vaults: The Adventures of Bigfoot

I've not written a lot of comics…but here's one I did, with an environmental theme, for Communities of Tomorrow via the Saskatchewan Science Centre. It appeared (maybe it still does, I'm not sure) in an exhibit at the Science Centre. I don't think it was ever actually printed as a comic per se.

The art work is by Ward Schell, with colors and lettering by Betta Shum. Click on each panel to see it larger.

***

February 17, 2012

The Rapunzel Number