Edward Willett's Blog, page 54

April 21, 2012

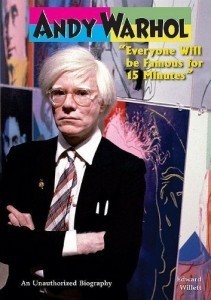

Saturday Special from the Vaults: Andy Warhol: Everyone Will Be Famous for 15 Minutes

For this week’s Saturday Special, another opening to another biography written for Enslow Publishers, this one about artist Andy Warhol. Like my biographies of Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix, it was for the series American Rebels. I actually studied a bit of art history and minored in art at university, and we make a point of visiting art galleries wherever we go, so this one was fun. Even more so since a Warhol exhibit passed through Regina while I was in the early stages of working on it.

For this week’s Saturday Special, another opening to another biography written for Enslow Publishers, this one about artist Andy Warhol. Like my biographies of Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix, it was for the series American Rebels. I actually studied a bit of art history and minored in art at university, and we make a point of visiting art galleries wherever we go, so this one was fun. Even more so since a Warhol exhibit passed through Regina while I was in the early stages of working on it.

Herewith, the introduction and first chapter to Andy Warhol: Everyone Will Be Famous for 15 Minutes.

But first: a link where you can buy the book!

Andy Warhol: Everyone Will Be Famous for 15 Minutes

Introduction

On July 9, 1962, a most unusual art exhibition opened in the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. It consisted of thirty-two paintings of Campbell’s Soup cans—one painting for each flavor of soup the company offered—wrapped around the gallery on a narrow white shelf, very much as if they were real cans on display in a supermarket.

The gallery owner, Irving Blum, didn’t do much to advertise them. He simply sent out a postcard of a tomato-soup can inviting interested buyers to stop by. There was no official opening. The paintings, measuring 20 by 16 inches each, were priced at $100 each.

Visitors to the gallery were “extremely mystified,” Blum said later. Another gallery not too far away bought dozens of real Campbell’s soup cans, put them in the window, and offered to sell them cheaper: just 60 cents for three cans. “There was a lot of hilarity concerning them,” he noted, but no serious interest from collectors (actor Dennis Hopper bought one, but in all only six were sold).[1]

Despite the lack of buyers, the paintings attracted a lot of publicity—both good and bad. Critics and viewers alike either liked them or loathed them.

The publicity began two months before with an article in TIME magazine, published May 11, 1962. “It was said of Zeuxis, the great artist of ancient Greece, that he could paint a bunch of grapes so realistically that birds would try to eat them,” wrote TIME. “This was an impressive skill, but art has long since aspired to more than carbon-copy realism.”

But “a segment of the advance guard,” a group of painters unknown to each other, TIME went on, “has suddenly pulled a switch,” coming to the conclusion that “the most banal and even vulgar trappings of modern civilization can, when transposed literally to canvas, become Art.”

Among the painters briefly mentioned in the article was a 30-year-old New York-based commercial artist named Andy Warhol, who, TIME noted, “is currently occupied with a series of ‘portraits’ of Campbell’s Soup Cans in living color.”

“I just paint things I always thought were beautiful, things you use every day and never think about,” Warhol told TIME. “I just do it because I like it.”[2]

The article was entitled “The Slice-of Cake School,” but a new name for it, Pop Art, was already taking hold. Within a few years, Warhol had become the Prince of Pop, the most famous creator of this new style of art so different from what had come before.

Eventually the Pop Art movement sputtered out, but Warhol’s fame continued. For the last 25 years of his life, he was one of the most famous and recognizable people in the world.

He wasn’t necessarily one of the most liked, however. Controversy constantly swirled around him. People loathed him or loved him, applauded him or reviled him. Some swung from one extreme to the other: one former associate and admirer eventually tried to kill him.

“In the future everybody will be world-famous for 15 minutes,” Warhol once famously said.3[3] But his own fame lasted a lot longer than that. Indeed, he’s as famous—and as controversial—now as he was when he died more than 20 years ago, with new exhibitions of his work mounted on a regular basis around the world.

Those Campbell Soup Can paintings? Irving Blum bought them back from Dennis Hopper and the others who had bought a few, then purchased the entire set from Warhol for $1,000.

In 1996 the Museum of Modern Art acquired them from Blum for an estimated $15 million.[4]

Warhol would have loved that.

A trendsetter rather than a trend-follower, a dispassionate observer of both the seamy and celebrity sides of life, Warhol was a true American rebel.

And in true American fashion, his life started in very humble circumstances.

Chapter One: Early Days

Andy Warhol told a lot of stories about his childhood after he was famous. He’d talk about having to eat soup made with tomato ketchup while growing up in the Depression. He talked about his father being a coal miner who died when he was young, and whom he hardly saw. He said his brothers bullied him, that his mother was always sick, that nobody liked him, that he never had any friends, that his skin turned white and his hair fell out by the time he was twelve.[5]

A lot of the stories weren’t true. But Andy Warhol was never someone to let truth get in the way of a good story—especially about himself.

Born in Pittsburgh

Andy Warhol was born Andrew Warhola on August 6, 1928, to Ondrej and Julia Warhola, in his parent’s bedroom in a narrow red-brick house at 73 Orr Street in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He had two older brothers, Paul, born on June 26, 1922, and John, born on May 31, 1925.

Ondrej and Julia were recent immigrants from the Ruthenian village of Mikova, located in the Carpathian Mountains (known in popular culture as the home of the vampire Dracula) near the borders of Russia and Poland.

Ondrej was born in Mikova on November 28, 1889. The Warhola family were devout, hard-working people, and Ondrej grew up working in the fields. When he was seventeen he decided there was no future in his homeland and he emigrated to Pittsburgh. After working there for two year, he went back to Mikova to find a bride.

He found Julia Zavacky, born in Mikova on November 17, 1892, one of a family of 15 children (though only nine survived until Julia was in her teens). Her brothers, John and Andrew, had already moved to Pennsylvania. According to Warhol biographer Victor Bockris, who interviewed family members extensively for his book Warhol, Julia and her sister, Mary, wanted to be famous singers, and even sang with a gypsy caravan in the Mikova area for a season. Julia was also artistic, making small sculptures and painting designs on objects. When she was sixteen her father told her it was time for her to get married. When Ondrej Warhola, who had just been the best man at the wedding of Julia’s brother, John, in Pennsylvania, returned and wanted to marry her, she at first refused; but her father beat her and then asked the priest to tell her to marry him. “Andy (Ondrej) visits again. He brings candy, wonderful candy. And for this candy, I marry him,” she used to say.[6] The couple lived in Mikova for three years, then Ondrej went back to Pittsburgh on his own to avoid being drafted into the army of Emperor Franz Joseph to fight in the First Balkan War. The couple wouldn’t see each other for nine years.

Julia was pregnant when Ondrej left, and gave birth in 1913. The baby, a girl, died of influenza when she was just six weeks old. Not long after that Julia heard that her brother Yurko had been killed in the war. It later turned out the news was a mistake, and he had survived, but the shock of the news may have contributed to the death, just a month later, of Julia’s mother. That left Julia to look after her little sisters, Ella and Eva, who were just six and nine.

Things went from bad to worse. The First World War broke out. The area was ravaged. Julia’s house was burned down. Ondrej’s brother George was killed. Several times she had to hide out in the woods with her little sisters and the old woman who helped care for them to escape approaching soldiers.

When the war ended, Ondrej began trying to bring Julia over to the United States. In 1919 he tried to send her the fare five times, but none of the money reached her. In 1921, she finally took matters into her own hands. Just before the United States embargoed immigration from Eastern Europe, Julia borrowed $160 from a priest and used it to travel by wagon, train, and finally ship to find her husband in Pittsburgh.

By the time Andy was born Ondrej, then thirty-eight years old, was a bald, muscular man who worked twelve hours a day for the Eichleay Corporation, a company that built roads and moved houses (not the contents of the houses: the houses themselves, to make way for new construction). Although he didn’t work in a coal mine, as Andy sometimes claimed, it was true that he was often away, called out of town on work for weeks or months.

Julia, thirty-five, had not been assimilated into American life as well as her husband. She still couldn’t speak a word of English. She typically wore a long peasant dress under an apron, and covered her head with a babushka. Both Julia and Ondrej were devout Byzantine Catholics who walked their family six miles to mass every Sunday morning.

The Depression hits home

In 1930 the family moved into a larger house at 55 Beelan Street. Julia’s sister Mary lived nearby. Two other brothers and another sister lived not too far away, and Ondrej’s brother Joseph also lived in the neighborhood. Between them and their families, little Andek (as his mother called him) grew up surrounded by relatives.

As the Great Depression took hold, the family (like many others in America at the time) suffered economically. Ondrej lost his job. Fortunately, unlike many men, he had managed to save several thousand dollars from his earnings during the 1920s. Now he had to rely on those savings to feed his family, but at least he had them: on January 16, 1931, relief organizations in Pittsburgh noted that 47,750 people were at starvation level in the city.[7]

Nevertheless, they were forced to move again, into a two-room apartment on Moultrie Street, where all three boys had to sleep in the same bed. The crowded conditions probably contributed to tensions between Paul and John, who often fought each other. Julia began working part time, cleaning houses and windows. She also made flower sculptures out of tin cans. Paul sold newspapers on streetcars for nickels and dimes.

When Andy was four years old, his father regained his job with the Eichleay Corporation and was once again called away frequently on jobs, leaving Paul, then ten years old, as head of the household. He was having his own problems at school. He hadn’t been able to speak English when he started first grade, and as a result he hated public speaking, a problem which became worse when he developed a speech impediment. He began to skip school, and he began to take out some of his frustrations by disciplining his little brother.

He apparently needed some discipline, though his big brother probably wasn’t the best person to administer it. “You could see he was picking up things much better than we had, but he was mischieful[EW1] between the ages of three to six,” Paul said later. Andy was picking up bad language from kids in the street and using it around his relatives. “The more you smacked him, the more he said it, the worse he got.”[8]

In September of 1932, when Andy has just turned four, Paul decided he should be registered for school. But the first day went badly—a girl slapped him, and of course he was two years younger than any of the other students—and Julia told Paul not to force him to go back. For the next two years, while Paul and John were in school, Andy was alone with his mother.

Julia was very creative herself. Not only did she draw pictures (her favorite subjects were angels and cats), she also loved embroidery—fabrics she’d embroidered decorated their home—and enjoyed making beautifully decorated Easter eggs.[9] When she was alone with Andy, she would draw pictures with him: portraits of each other, sometimes, or pictures of the cat.

New neighborhood, new friends

In early 1934 the Warhola family moved again, this time into a house at 3252 Dawson Street in the Oakland neighborhood of Pittsburgh. Ondrej paid $3,200 for the two-story brick house, which was much nicer than anything else the family had lived in up to that point. Andy would live there until he moved to New York fifteen years later. He and John shared a bedroom; Paul converted the attic into a third bedroom for himself. There were lots of boys around, playing horseshoes, softball or baseball, going swimming in Schenley Park, playing craps. But, remembers a neighbor, “Andy was so intelligent, he was more or less in a world all of his own, he kept to himself like a loner.”[10]

When Andy did play with other children, he usually preferred to play with girls. His first best friend at Holmes Elementary School, located just half a block from the Warholas’ new house, was a little Ukrainian girl named Margie Girman. They’d go to the movies together on Saturday mornings. At the theater, for just eleven cents, children got an ice-cream bar, a double feature, and a signed eight-by-ten glossy photograph of one of the stars. Andy collected them and soon had a whole box of them.

When Julia would take her children to visit her family in Lyndora, Pennsylvania, Andy’s best friend was Lillian “Kiki” Lanchester. When they went to visit Julia’s sister Mary, Andy’s best friend was his cousin Justina, nicknamed Tinka. She was four years older than Andy and more like a big sister than anything else.

Even though Andy had only been at Soho Elementary in their old neighborhood for one day when he was four, he was credited with having completed the first grade there, and so went straight into Grade 2 at Holmes Elementary, at the age of six. Even then, his teacher Catherine Metz remembered later, “he was real good at drawing.”[11]

Andy liked school and did well in it—and all the time he was drawing. Julia encouraged him, even buying a movie projector (without her husband’s knowledge) so he could watch black-and-white silent cartoons, which inspired him to draw even more.

Andy had a number of health problems as he grew up. When he was two, his eyes would swell up and had to be washed with boric acid every day. When he was four he broke his arm—the arm he would eventually paint with—after tripping over the streetcar tracks. Nobody realized it was broken until it had healed crooked: the doctors had to re-break it so it could heal straight. When he was six he had scarlet fever. When he was seven he had his tonsils removed.

And then, in the autumn of 1936 when he was eight years old, he came down with rheumatic fever.

Eight weeks in bed

Rheumatic fever is less common in the United States than it used to be, although outbreaks are still common in the developing world. It’s a complication of strep throat in which the bacteria that cause strep move into the rest of the body, producing inflammation that can include damage to the heart, joints, skin—and brain.[12]

If the brain is affected, the inflammation can cause loss of coordination and uncontrolled movement of the limbs and face. Technically this is called chorea, but a more common name for it is St. Vitus’s dance. In the 1930s doctors weren’t sure what caused it, but they did know that it usually disappeared on its own within weeks or months.

Teachers at Holmes Elementary had already discovered Andy’s artistic talent, but now he found when he tried to draw on the blackboard his hand would begin to shake. He had trouble writing his name or tying his shoes. The other kids laughed at him and began to pick on him and beat him up. Suddenly school became a terrifying place.

His family didn’t notice the symptoms at first, but once he started having trouble talking or sitting still and began fumbling things. they finally called the doctor. He ordered Andy to stay in bed for a month.

Andy loved it. He had his mother all to himself, and didn’t have to deal with the bullies at school or his brothers or father. His mother gave him movie magazines and comic books and coloring books and moved the radio into the dining room, where his bed had been placed. Once his hands stopped shaking, Andy spent hours coloring, making collages with cut-up magazines and playing with paper dolls.

After four weeks he was supposed to go back to school, but he suffered a relapse and had to go back to bed for another four weeks. After the second four weeks, he’d developed one of the other possible complications of rheumatic fever: large reddish-brown patches on his skin.

In addition to blotches, rheumatic fever can cause lumps or nodules to appear beneath normal-appearing skin. Bad skin would plague Andy for the rest of his life.

Those eight weeks in bed proved to be important to Andy Warhol’s eventual development as an artist. In the movie magazines and through the radio, he immersed himself in a rich fantasy world, one filled with celebrities and centered on the two centers of American popular culture: Hollywood and New York. His most prized possession for years was a personalized signed photograph of Shirley Temple. He went so far as to emulate many of the child actress’s gestures, carrying them on into adult life. His fascination with celebrities would be a driving force for much of his career.

Those eight weeks also contributed a great deal to the development of his personality. Back in school, the bullying slacked off. Andy was now seen as slightly eccentric and somewhat frail. His brothers began standing up for him more. He played on all of that to his benefit.

Many years later, Warhol wrote, “I learned when I was little that whenever I got aggressive and tried to tell someone what to do nothing happened—I just couldn’t carry it off. I learned that you actually have more power when you shut up, because at least some people will start to maybe doubt themselves.”[13]

Or as Victor Bockris puts it, “His two-sided character began to emerge. While continuing to be as sweet and humble as ever with his girlfriends, he began on occasion to act like an arrogant little prince at home.”12[14]

That home was soon to undergo another major upheaval, with the death of Andy’s father.

INTRODUCTION

[1] Bockris, Victor. Warhol. (New York: Da Capo Press, 1997). p. 149.

[2] “The Slice-of Cake School.” Time Magazine, Friday, May 11, 1962. . (November 5, 2008).

[3] Kaplan, Justin, ed. Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, 16th Ed. (New York: Little, Brown & Co., 1992), p. 758.

[4] Vogel, Carol. “Modern Acquires 2 Icons Of Pop Art.” The New York Times, October 10, 1996.

CHAPTER ONE

[5] Bockris, Victor. Warhol. (New York: Da Capo Press, 1997), p. 15.

[6] Guiles, Fred Lawrence. Loner at the Ball: The Life of Andy Warhol. (New York: Bantam Press, 1989), p. 12.

[7] “Chronology by Year: 1931.” Historic Pittsburgh. (June 4, 2009).

[8] Bockris, p. 24.

[9] “Julia Warhola – Andy Warhol’s Mother.” The Andy Warhol Family Album. (November 5, 2008).

[10] Bockris, p. 33.

[11] Ibid, p. 35.

[12] “Rheumatic Fever.” Mayo Clinic.com < http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/rheu.... (November 6, 2008.)

[13] Hackett, Pat and Warhol, Andy. POPism: The Warhol Sixties. (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980.)

[14] Bockris, p. 41.

April 14, 2012

Saturday Special from the Vaults: The Shepherd

This is another really early story; in fact, I’d completely forgotten about it until I found the file on my hard drive. I must have written it when I was 21 or 22. I was pleasantly surprised it holds up as well as it does.

It was never published, though I think I submitted it a few times.

***

By Edward Willett

Danell woke.

Dream-images of warriors with bright swords and glittering armor shattered around him, and he was left with only his narrow cot, his patched wool blanket, and the aftertaste of the bitter disappointment he had taken to bed with him.

Today had been the day of the great fair and market in Kingsholm. The King himself had been there, and all his mighty knights. There had been a tournament; displays of magic and music; plays and acrobats; food and wine overflowing. His father had been there, selling their sheep, and his brothers had been there, enjoying themselves, and he—

He had been left behind to look after his year-old sister, Teriss. His father knew how much he loved the old tales of war and wizards, how much it would have meant to him to see the King who won those glorious victories and watch his men wage mock war in the tournament. Surely his father knew he dreamed of becoming a squire and maybe even a knight himself someday. And it wasn’t as if Barett and Guildor had never been to Kingsholm before; they’d both been to the last fair. He’d never been at all.

But his father hadn’t been moved by any of his arguments. “You’re not old enough,” he’d said. “Kingsholm at fair-time is no place for a boy. You’ve filled your head with silly dreams. You’d go off with the first landless knight who needed a slave to curry his horse.”

“You don’t trust me!”

“I trust you enough to leave the farm and your sister in your safekeeping,” his father replied. “What you need to learn, my boy, is what’s really important. Dreams are fine, but this farm is wide-awake reality. You’ll get a good dose of it, being on your own today. You’ll find it a lot easier to reach for dreams if you keep your feet on the ground.”

And that had been that.

Still angry at the complete unfairness of it, he sat up and looked around the room, dimly lit by moonglow through the narrow window. Teriss had not awakened him; the only sound from her crib in the corner was her faint breathing.

A flash brighter than the moonlight flickered in the shape of the window on the stones of the far wall. Seconds later a bass rumble followed.

Satisfied he had been disturbed only by the approaching storm, Danell lay back and rolled over on his side, anxious to plunge into his heroic dreams again. Then he heard a voice outside, answered by a second, and a third.

He sat back up in a hurry. The voices were not those of his two older brothers, Barett and Guildor, though he expected them to return some time during the night. Nor could his father be out there; he would be at market two or three days.

Danell slipped out of bed and went to the window. A light breeze drew cold fingers across his bare skin, and he shivered. He could see nothing but a narrow swath of the farmyard, but the voices, when they came again, were nearer—the deep, thick voices of men.

“Easy as cracking eggs. The old man and his grown sons are gone.”

“What about the youngest boy?”

“What about him? He’ll be asleep. Even if he’s not, what can he do against three of us? We’ll slit his throat and take our time finding the gold…”

Danell stepped away from the window, his heart pounding. Robbers!

His first thought was for the gold, the gold his father had saved, coin by coin, over years and years of taking the sheep to market, the gold he’d kept hidden against some day of disaster, drought or disease. But then Teriss murmured in her sleep, and the gold seemed less than nothing.

If they planned to slit his throat, would they hesitate to kill her, too?

Danell didn’t even know how long he had. He had to decide what to do at once.

He had his sling and he could use it well—he’d once killed a sheep-stalking mountain cat with it—but in the dark, against three, it wouldn’t be enough.

There was no place to hide in the house. That meant he had to get outside.

Quickly he pulled on trousers and tunic, but left his sandals and cloak. Bare feet would serve him better, and the cloak would only be in his way.

He opened the wardrobe his father had made for his mother only last fall, and pulled down clothes to make a nest in the bottom, thinking sadly as he did so that though his mother hadn’t lived long enough to make use of the gift, it could now serve the daughter she had died giving birth to. He lay Teriss down on the clothes; she moved sleepily but did not wake, and he softly closed the door.

Next he ran into the kitchen and reached inside the chimney, feeling for the loose rock that—there! In the space behind it was a heavy leather pouch that jingled as Danell pulled it free. Slinging the pouch over his right shoulder, he reached into it and grabbed a handful of coins. Then, clenching them in his fist, he lifted the latch on the kitchen door and stepped outside.

Lightning flared, silhouetting the three robbers only a few feet away. Danell gasped as they lunged at him, then twisted away, dropping the coins he had in his hand. One of the thieves grabbed the neck of his tunic, but the material tore away and Danell ran for the trees.

He heard curses behind him: then lightning flashed again and the robbers saw the coins he had let fall. “The brat has the gold on him!” one yelled. “After him!”

Danell slowed down inside the forest and turned uphill. He knew these woods and the meadows further up; all his life he had kept sheep on the mountain, and on more than one stormy night had scoured the slope for a lost lamb. His bare feet made no sound in the leaves and twigs of the forest floor, while behind him the thieves crashed through the underbrush. They fell further and further back.

Lightning came again, followed close on its heels by thunder, and the rising wind drowned out the last faint sounds of his pursuers. Danell slowed to a walk, drawing breath. No doubt the robbers were still after him, but he had gained some time.

Above the patch of forest surrounding the house was the meadow where the sheep grazed during the day, before being bedded down in the fold, well away to his right. To his left rose a ridge, a shoulder of the mountain, that on the other side fell steeply to a cataract in a deep gorge.

Danell headed up toward the edge of the meadow, planning to cut left and climb over the ridge. With it between him and the woods where the thieves would continue looking for him, he would head down the mountain for help. His brothers had to be on the road home, maybe close by. And since he had the gold, the thieves would continue looking for him and leave the house and Teriss alone.

He hoped.

He broke out of the trees. Before him rose the grassy, rock-strewn meadow where he had spent many happier days. Lightning and thunder mingled in glare and cacophony overhead and the howling wind, whipping over the grass, hit him full force as he left the trees behind. Blowing off the snows of the peak, it seemed to suck all warmth from his body.

Hastily he turned left and, leaning into the gale, started for the ridge, a quarter of a mile away, sticking close to the tree line for as much cover as possible, both from the storm and from hostile eyes behind him. By the time he reached the ridge the chill in his limbs had become pain, and the first drops of rain spattered down, each as solid and cold as ice.

The thin, twisted trees on the ridge scarcely broke the wind. Danell scrambled up among them as quickly as he could, head lowered. As he crested the slope he could hear the roar of the river even above the storm. Swollen by rain upslope, the swift, splashing stream had become a torrent.

The rain thickened, until in seconds it fell so hard that even in the full glare of the lightning Danell could see only a few yards. Soaked and shivering, he began to descend the mountain, clinging to branches along the top of the ridge, feet sliding dangerously on the wet grass.

His confidence waned as the storm waxed. Shouldn’t he have fled with Teriss herself, instead of the gold? He had escaped with it, he could just as easily have escaped with her.

A knife-like slash of wind-blown rain across his face made him stumble, and he shook his head violently. Teriss would not have survived such a night. He took another step and slid for a heart-stopping instant toward the gorge before catching a branch. He might not survive it either!

Sheep are safe when the wolves hunt elsewhere, he thought. The wolves are hunting me; the lamb is safe.

Then he looked up and screamed. Like something out of a nightmare, one of the robbers appeared in front of him in a flash of lightning, naked sword in hand. The blade reached out toward his throat. “Give me the gold, boy!” Danell didn’t move—couldn’t move. Sharp steel bit his cold-numbed flesh. “The gold!”

The wolves had hunted him down…and when they had him they would return to the fold to take whatever else was there—including the lamb, Teriss.

Slowly Danell let the strap of the pouch slide from his shoulder into his hand. Then, “Take it!” he screamed, and with his slinger’s skill whipped the pouch in a half-circle and released it.

The gold-weighted bag smashed into the robber’s chest. He staggered back, arms flailing, the sword flying from his hand. Lightning flashed and Danell glimpsed a white face and staring eyes—then darkness returned and the man was gone. For an instant, a scream echoed above the sound of wind and river.

Danell, his own eyes wide and his heart pounding, flung himself up and over the ridge and down the other side, back into the forest. He ran through the trees, branches clutching at him, tearing clothes and skin. Twice he fell and stumbled back up to run again. The third time he crashed down so hard he couldn’t breathe for a moment, and lay curled in misery on the wet leaves of the forest floor, struggling for air.

In a burst of lightning he saw he was at the edge of the trail down the mountain. With his first shallow, painful breaths he staggered to his feet and stumbled onto the path—and saw the remaining two thieves not twenty feet upslope.

Danell didn’t have enough air in his lungs to run. He fell to his knees as the robbers ran toward him, swords drawn. One of them grabbed his hair and yanked his head back “Where is it? Where’s the gold?”

“The river,” Danell choked out. “With your friend.”

The robber flung him to the ground. “You’re lying!”

“I think he’s telling the truth,” the other man said. “I thought I heard a scream—”

The first robber stared at him, then down at Danell. “All that gold—in the river—” He raised his sword. “I’ll kill you for that!”

His blade whistled down, but Danell rolled out of the way, scrambled to his feet and pelted down the path. The robbers followed, screaming oaths.

Danell’s feet felt leaden and his chest still ached. Soon, very soon, he would fall, and they would kill him, and then they would go back to the house and Teriss would die, too . . .

He rounded a corner. Blinded by the rain and his terror and exhaustion, he didn’t see the two men on the trail until he careened into them. Strong arms grabbed him, then supported him. “Danell! What’s wrong?”

With overwhelming relief, Danell recognized the voice of Barett, his oldest brother. “Robbers!” he gasped. Barett thrust him out of the way, and he heard the ring of swords being drawn.

The ensuing battle was brief.

#

Wrapped in a blanket, Danell steamed by the roaring fire in the kitchen hearth. “I thought I’d never be warm again,” he said, and edged closer to the blaze.

Barett sat at the table with Teriss in his arms. The baby tried to grab his finger, laughing. Guildor turned from the fire and smiled at his little sister as he handed Danell a steaming mug of mulled wine.

Danell cupped it in his hands. “What will father say about the gold? He’s been saving that for so many years…”

Barett glanced up at him. “He’s always said he was saving it for a disaster,” he pointed out. “If you hadn’t used it as you did, tonight would have been the worst disaster of all. You know he isn’t concerned about gold as much as he is about you—and Teriss.”

“I didn’t think so this morning,” Danell admitted. “I didn’t think it was fair. He knows how I feel…” His voice trailed off. He felt only embarrassment now at the way he had acted that morning, and gulped wine to hide his flush.

Guildor and Barett exchanged glances, then Guildor said, “That was a very brave thing you did. Worthy of a great hero, if you ask me.”

Danell remembered cold, terror, violence and pain. He sipped from the cup again and shook his head. “If that’s what it means to be a hero—then to be a shepherd is the finest thing I know.” No dreams of knights or bold battles filled his head now; he had fought his battle, and to sit in peace and safety with his brothers and sister was all he could ask. He looked at Teriss, laughing as she played with Barett’s hand, and added, “Besides, all I was really doing was looking after a very special lamb.” He grinned and snuggled down in his blanket. “The ones with fleece are less trouble.”

#

April 12, 2012

The QWERTY effect

I took to typing like…well, like a writer to a keyboard. In high school I was always the fastest typist in typing class. Possibly it was genetic: my mother, who worked as a secretary, was a very fast typist. Possibly it was because I was highly motivated: my handwriting was (and is) atrocious.

I took to typing like…well, like a writer to a keyboard. In high school I was always the fastest typist in typing class. Possibly it was genetic: my mother, who worked as a secretary, was a very fast typist. Possibly it was because I was highly motivated: my handwriting was (and is) atrocious.

Anyone who has learned to touch type has probably wondered about the peculiar arrangement of the standard keyboard, usually called QWERTY. Why aren't the letters in, say, alphabetical order?

The fact is, some of the earliest typewriters did have keyboards in alphabetical order. But they had a problem: alphabetical order put some frequently used letter pairs too close together on the keyboard, resulting in mechanical clashes.

QWERTY was invented in 1868 and adopted by Remington for the Sholes and Glidden Type-Writer, whose brand name eventually became the generic name of all such machines—one sure sign of a commercial success.

The other sign of the machine's success is the fact that its QWERTY layout was soon adopted by all other manufacturers.

QWERTY was designed to prevent the mechanical clashes that arose in early machines when two adjacent keys were struck in quick succession. It did that by separating frequently used letter pairs to opposite sides of the keyboard. (It also, not coincidentally, contains all the letters for the word "typewriter" in the top row, allowing salesmen to easily demonstrate the machine.)

QWERTY is now everywhere, which means that most of what you read passed, at some time, through a QWERTY keyboard. And now there's research that suggests that the QWERTY arrangement actually affects the emotional content of what we read.

Linguists and psychologists talk about the "articulators" used in language production. They usually mean part of the vocal tract, but with so much language being produced using a keyboard, increasingly we're letting our fingers do our articulation for us.

In spoken language, a portion of the meaning of words is linked to the way they are articulated. Researchers Kyle Jasmin and Daniel Casasanto wanted to find out if the same held true for typed language.

How does this supposed effect work? The QWERTY keyboard is asymmetrical: there are actually more letters on the left side of the midline than on the right. This means it is slightly more difficult to type words that use left-side letters than those that use right-side letters (something which has been demonstrated experimentally).

The researchers decided to test the hypothesis that "right-side words," because they are easier to type, might be viewed more positively than left-side word. Not only that, but this might carry over to spoken language, because touch-typists (like me) actually implicitly activate the positions of keys when they read words.

To test this, Jasmin and Casasanto conducted three experiments, using three QWERTY-using languages (Dutch, Spanish, and, of course, English.) In the first, they set out to find out if the QWERTY effect carried across different languages—and found that it did. They showed participants a list of words and had them rate the emotional "valence" on a scale of one to five (using "manikins," a smiling figure at the positive end and a frowning figure at the negative end). Overall, words with more right-side letters were rated to have a more positive meaning than words with more left-side letters.

Next, they tested whether QWERTY influences new words more than old words…and found that the QWERTY effect was indeed more apparent in words coined after the invention of QWERTY.

Finally, they tested for the effect with pseudowords, made-up words with no meaning. (Science fiction and fantasy writers take note! We make up words all the time.) Sure enough, made-up words with more right-side letters were judged to have more positive meanings.

In the words of the researchers, "It appears that using QWERTY shapes the meaning of existing words and may also influence which new words and abbreviations get adopted into the lexicon and the 'texticon' by encouraging the use of words and abbreviations whose emotional valences are congruent with the letters' locations on the keyboard."

And the practical applications?

"People responsible for naming new products, brands and companies might do well to consider the potential advantages of consulting their keyboards and choosing the 'right' name."

And for what's it worth, I just realized that my name, Edward, is typed entirely using the left-hand keys.

It's a wonder I have any friends at all.

April 7, 2012

Saturday Special from the Vaults: Janis Joplin: Take Another Little Piece of My Heart

Another Enslow book, Janis Joplin: Take Another Little Piece of My Heart tells the story of another '60s rock star who died at age 27–within just a few weeks of Jimi Hendrix's death. Since I also wrote biographies of Johnny Cash and Andy Warhol for Enslow, I spent several months kind of stuck in the '60s. (I won't say "reliving the '60s, because I was a pre-teen in that decade and can't say any of the social or musical upheaval impacted much on my consciousness!)

Another Enslow book, Janis Joplin: Take Another Little Piece of My Heart tells the story of another '60s rock star who died at age 27–within just a few weeks of Jimi Hendrix's death. Since I also wrote biographies of Johnny Cash and Andy Warhol for Enslow, I spent several months kind of stuck in the '60s. (I won't say "reliving the '60s, because I was a pre-teen in that decade and can't say any of the social or musical upheaval impacted much on my consciousness!)

Enjoy! And if you feel so inclined, here's a link to the Amazon page where you can purchase the book.

Janis Joplin: Take Another Little Piece of My Heart

Introduction

On Saturday afternoon, June 17, 1967, a band with the unlikely name of Big Brother and the Holding Company took to the stage of the Monterey International Pop Festival at the Monterey County Fairgrounds, eighty miles south of San Francisco.

Big Brother's lead singer, a young woman named Janis Joplin, was nervous. She'd been singing with Big Brother for a year, and so far the group hadn't made much headway. They weren't a top draw even in San Francisco, their home town. Now here they were facing their biggest audience yet. Forty thousand people had turned out for the festival, but they were there to see Otis Redding and British imports like The Who and Jimi Hendrix. They weren't particularly interested in Big Brother, which was why the band had been given a slot on the program on Saturday afternoon, hardly prime time at a rock concert.

A documentary about the festival was being filmed by D. A. Pennebaker that weekend for ABC-TV, but the cameras weren't pointed at the stage when Big Brother and Janis Joplin launched into "Down on Me, "Road Block" and "Ball and Chain." Instead they were pointed at the audience, where they captured the overwhelmed response of Mama Cass of the hit group the Mamas and the Papa. "Mouth agape, her ears were in music lover's heaven," wrote Laura Joplin, Janis Joplin's sister, in her book Love, Janis.[i]

When Big Brother finished its set, the audience exploded. The organizers were dumfounded. Critics were ecstatic. Jazz critic Nat Hentoff wrote that Janis's performance left him limp and feeling that he'd been "in contact with an overwhelming life force." Greil Marcus, another critic, noted that Janis went so far out that he wondered how she ever managed to get back.[ii]

"When I sing," Janis Joplin once said, "I feel, oh, I feel, well, like when you're first in love…I feel chills, weird feelings slipping all over my body, it's a supreme emotional and physical experience."[iii]

At Monterey Pop, the audience felt the same way when they heard Janis Joplin perform. Brought back for an encore to ensure that this time, their performance would be filmed, Janis and Big Brother wowed the audience again.

For Janis, it was vindication. Letting her feelings take hold, letting it "all hang out," in the slang of the time, had been something she'd always been counseled against, something that had led to taunts and ridicule in high school and beyond. But now, she said, "I've made feeling work for me, through music, instead of destroying me. It's superfortunate. Man, if it hadn't been for the music, I probably would have done myself in."[iv]

Before Monterey Pop, few people had heard of Janis Joplin.

Afterward, almost everyone had. For the next three years, like a falling star, she would blaze a trail of outrageous behavior and incredible music across the pop-culture sky of 1960s America.

But then, also like a falling star, her light would abruptly go out.

Chapter 1: Frilled Frocks and Bridge

The short but eventful life of Janis Joplin began in what might be considered the most unlikely of places: Port Arthur, Texas.

Port Arthur, located in southeast Texas just off the Gulf of Mexico and just west of the Louisiana border, was founded (and named) by Kansas railway promoter Arthur E. Stilwell. Stilwell wanted to link Kansas City to the Gulf of Mexico by rail, because he had just launched the Kansas City, Pittsburg and Gulf Railroad. He and his backers acquired land on the western shore of Sabine Lake, a freshwater lake just inland from the Gulf and connected to it by a natural opening known as Sabine Pass.

Stillwell wanted the new city to be both a major tourist resort and an important seaport. A canal was cut along the western edge of the lake, connecting the site of the new town to deep water at Sabine Pass. Port Arthur was formally incorporated in 1898.[v]

Because Stillwell wanted Port Arthur to be a tourist destination as well as a major port, he planned beautiful broad boulevards and avenues and grand homes along the lakeshore. But early in the twentieth century Stillwell lost financial control of the project to John W. Gates, a Wall Street speculator whose nickname was "Bet-a-Million" and who had made his fortune selling barbed wire across the West. (The company he formed eventually became the giant corporation U.S. Steel.)[vi]

Gates extended and deepened the canal so that ships could sail it all the way to the cities of Beaumont and Orange. Unfortunately, that cut off Port Arthur from the lakeshore, ruining the view of the expensive lakeside homes and reducing Port Arthur's appeal as a tourist destination.[vii]

That appeal faded further as Port Arthur became inextricably linked to the burgeoning Texas oil industry. By the 1960s, the town buildings seemed almost lost among the huge oil refineries, storage tanks and chemical plants. And since in those days natural gas was simply released into the air, the whole "Golden Triangle," as the region encompassing the towns of Port Arthur, Orange and Beaumont is known, smelled like rotten eggs. Reportedly, at Lamar Tech, the college Janis Joplin would some day (briefly) attend, the fumes from a nearby sulfur plant were sometimes strong enough to melt the girls' nylons.[viii]

But oil also means money, and good jobs, and it was the need for both that brought Janis's parents to Port Arthur before she was born.

The flapper and the bootlegger

Dorothy East and Seth Joplin met in Amarillo, Texas, on a blind date. Dorothy, the daughter of Cecil and Laura East (nee Hansen), was known in Amarillo for her beautiful singing. She particularly liked Broadway show tunes, and in high school she won the lead role in a citywide stage production. The Broadway director the organizers brought in told Dorothy he could get her work in New York, but he recommended against it, because "those people just aren't your kind of folks."[ix] She took his advice and instead applied to Texas Christian University in Fort Worth. Disappointed that the university had only one voice teacher, who only taught opera, she returned to Amarillo after a single year and began helping at a radio station, KGNC. She was known as a "free spirit," scandalizing her parents by adopting the "flapper" styles of short hair, close-fitting dresses, snazzy hats and high heels. She also smoked and once accidentally swore on-air.[x]

In other words, she showed flashes of the same rebelliousness for which her daughter would later be notorious.

Seth Joplin was the son of Seeb (who ran the Amarillo stockyards) and Florence Joplin (nee Porter). At the time he met Dorothy East, he was taking a break from engineering studies at Texas A&M—studies he never finished: a lack of money forced him to give up his schooling still one semester shy of a degree. A bit of a rebel himself, he made bathtub gin during the last days of Prohibition and smoked marijuana (which was legal then). While courting Dorothy, he took the only job he could find, as a gas station attendant. Dorothy worked as a credit clerk in the local Montgomery Ward department store, eventually becoming head of the department.[xi]

In 1935, in the depths of the Depression, Seth got a break: his best friend from college recommended him for a job at the Texas Company (later Texaco) in Port Arthur. Dorothy quit her job to follow, and soon found work in the credit department at Sears. With two incomes they were finally able to afford to marry, which they did on October 20, 1936.

Seth worked at the only Texaco plant that made containers for petroleum. When the Second World War broke out, his job was considered so vital that although he was called to join the armed forces three times, each time he was deferred.

Shortly after Seth and Dorothy married, Dorothy's parents' marriage broke up. Dorothy's mother, Laura, and her younger sister, Mimi, came to live with Seth and Dorothy. Needing more space, they bought their first house, a two-bedroom brick bungalow on the edge of town. For fun, Dorothy and Seth liked to cross the Sabine River and party in the bars in Vinton, Louisiana.

In mid-1942, Dorothy became pregnant. Janis Lyn Joplin was born at 9:30 a.m. on January 19, 1943.

Janis Joplin makes her entrance

Janis was three weeks early and weighed only five and a half pounds, but she throve. After all, she had parents, a grandmother and an aunt doting on her. (However, Laura and Mimi moved out to a place of their own when Janis was three.)[xii]

As a child, Janis wasn't rebellious at all. In fact, Dorothy Joplin said later she was easy to care for—not too docile, but not overactive, either—and cheerful by nature.

Janis's mother, who believed a mother's place was at home, quit her job to look after Janis full time. She made her beautiful dresses and blouses with ruffles and ribbons and frills, and took her to the First Christian Church for church school, which Dorothy eventually taught.

Seth, who started work at 5:30 a.m., got to spend time with his daughter when he got home in the afternoon. Janis would wait for him on the front porch, he'd give her a hug, and they'd sit and talk.

One day Dorothy overheard her husband telling Janis about making bathtub gin in college. "'Is that the proper topic for a conversation with a child?' she asked him later," Laura Joplin, Janis's younger sister, wrote in her biography of Janis, Love, Janis. "Pop refused to argue the point; instead, he quit spending the evening time visiting with Janis on the front step. Janis was crushed and never knew why."[xiii]

Janis's mother introduced her daughter to music well before she started school. She bought an old upright piano and taught Janis how to play it. "She and Janis sat on the piano bench together, with Janis singing the simple nursery songs Dorothy taught her," Laura wrote. "Janis often lay in bed at night singing those songs, over and over, to put herself to sleep."[xiv]

But Janis's father found the noise of a child practicing scales annoying. As well, Dorothy had recently undergone an operation to remove her thyroid gland. The operation destroyed her singing voice (although her speaking voice was fine). Seth Joplin thought having the piano around would be too emotionally painful for his wife, so the piano was sold, ending Janis's first flirtation with formal musical training.[xv]

In 1949, after two miscarriages, the Joplins had a second child, Laura Lee, and moved to a larger three-bedroom house at 3130 Lombardy Drive, in a neighborhood called Griffing Park. Four years later, in 1953, Janis's brother Michael Ross was born.

Janis was bright, friendly and inquisitive. Laura wrote, "She had a full face, small, twinkling blue eyes, a broad forehead that Mother always said showed her intellect, and fine, silky blond hair that had a soft curl in it…People might have found her features plain if a buoyant spirit and zest for life hadn't overshadowed her looks. She was a child who liked people. She always made strangers welcome. Her sensitivity to others showed in a considerate willingness to go out of her way to include others in play."[xvi]

Aside from singing herself to sleep and singing in the church choir (and, in junior high school, in the Glee Club), Janis showed no particular aptitude for or interest in music. She was much more interested in art. She began to draw as soon as she could hold a pencil. Her mother even arranged private art lessons for her when she was in the third and fourth grades.

Janis also loved to read, a love that continued throughout her life. She learned to read before she entered school and had a library card even before that.

Janis Joplin: her own tall tale?

Dorothy Joplin said that Janis particularly loved magical, fantastical tales. (In one of the letters in Laura Joplin's book Love Janis, Janis recommends J.R.R. Tolkien's books The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings to her younger sister.)

"She studied about the theater. She studied 'tall tales of America,'" Dorothy said. She wondered if some of the over-the-top accounts of her own escapades Janis told the press once she became famous were her own versions of those tall tales.

"She'd spin these tales. It was so far out that you were supposed to understand that it was that way. She tried the same thing with the press–in my opinion. And it backfired.

"I overlooked that marvelous capacity of hers to trust people."[xvii]

Janis even began writing her own plays in the first grade and staging them with her friends as puppet shows in a puppet theatre her mother built for her in the back yard.

A "strikingly timid child"

Janis entered junior high with a good but unspectacular academic record. Several of her childhood friends moved out of town when she was in the sixth grade, and she had to ride a bus to the junior high, which was further away than her grade school had been. She found the rowdy kids on the bus frightening—she was a "strikingly timid child," Myra Friedman wrote[xviii]—but once she started traveling to junior high via a car pool instead of on the bus, she adjusted quickly. Her mother didn't remember any behavioral problems at all. "I even worried about it a little," she said. "She never did anything for me to correct!"[xix]

The limitations of Port Arthur meant that finding something interesting for the whole family to do took some imagination on the part of Janis's father. He hit upon taking them down to the Post Office to look at the Wanted posters. "It was a little unusual," he agreed later, "but it was somewhere to go. That wasn't the real reason, the Wanted Men. We'd just roam around the deserted building and read about all the people who were wanted for murders. We'd go any unusual place we could."[xx]

Everyone who knew Janis when she was a child praised her when Myra Friedman interviewed them not long after Janis's death. "Janis helped out in the library; Janis helped out at the church. Janis won an artwork contest for the cover of a junior high publication; Janis did posters for the library. Janis was cooperative; Janis was shy. Janis was 'just like everybody else,'" she wrote.[xxi]

But in junior high, as Janis approached adolescence, signs began to appear that perhaps Janis wasn't "just like everybody else" after all. Her teachers began to give her unsatisfactory marks in work habits and citizenship because she "talked too much and didn't get her work done on time," her sister Laura noted. "…She was more inquisitive and energetic than the school program allowed." [xxii] She was also, according to her friends, naïve and gullible, someone who could be led to believe all kinds of preposterous stories and who was always eager to please other people.[xxiii]

Janis did all the things expected of a proper young girl in Port Arthur in the 1950s. She joined the Junior Reading Circle for Culture, and Tri Hi Y club, and the Glee Club, which gave her her first public singing opportunity outside of church: she sang a solo in the Christmas pageant. She even took bridge lessons. (Bridge was a passion of her parents'.) In fact, she met her first boyfriend, Jack Smith, when they played bridge together in the seventh grade in the Ladies Aid Society's 'Bridge for Cultural Improvement' club.[xxiv]

Despite occasional problems with talking too much in class or doodling when she should have been taking notes, Janis seemed destined to sail smoothly into Port Arthur society, following the course prescribed for young ladies: high school, university, marriage, house, kids.

But in high school, smooth sailing gave way to stormy waters.

[i] Joplin, Laura, Love, Janis, New York: HarperCollins 2005 p. 237.

[ii] Echols, Alice, Scars of Sweet Paradise: The Life and Times of Janis Joplin, New York: Metropolitan Books 1999 p. 165.

[iii] Ibid, p. 166.

[iv] Ibid, p. 168.

CHAPTER ONE

[v] Storey, John W., "Port Arthur, Texas," The Handbook of Texas Online, (September 22, 2006).

[vi] Joplin, Laura, Love, Janis, New York: Penguin Books 1992 pp. 22-23.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Echols, Alice, Scars of Sweet Paradise: The Life and Times of Janis Joplin, New York: Metropolitan Books 1999 pp. 4-5.

[ix] Joplin, p. 19.

[x] Ibid, p. 20.

[xi] Ibid, p. 21

[xii] Ibid, p. 22-24

[xiii] Ibid., p. 25

[xiv] Joplin, p. 25.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Joplin, p. 27.

[xvii] Friedman, Myra, Buried Alive: The Biography of Janis Joplin, New York: Harmony Books 1992, p. 10.

[xviii] Friedman, p. 11.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] Ibid, p. 12.

[xxi] Ibid, p. 13

[xxii] Joplin, p. 38.

[xxiii] Friedman, p. 14.

[xxiv] Ibid., p. 15.

March 31, 2012

Saturday Special from the Vaults: The Bounty Mutiny: From the Court Case to the Movie

One of the more interesting projects I undertook for Enslow Publishers was a history of the famous Mutiny on the Bounty, comparing the real-life events to the way they were portrayed in the movie starring Anthony Hopkins as William Bligh and Mel Gibson as Fletcher Christian that came out in the 1980s. I've always enjoyed reading about life at sea in the 19th century, so this was a natural fit. And honestly, what other book of mine is likely to have Anthony Hopkins and Mel Gibson on the cover?

One of the more interesting projects I undertook for Enslow Publishers was a history of the famous Mutiny on the Bounty, comparing the real-life events to the way they were portrayed in the movie starring Anthony Hopkins as William Bligh and Mel Gibson as Fletcher Christian that came out in the 1980s. I've always enjoyed reading about life at sea in the 19th century, so this was a natural fit. And honestly, what other book of mine is likely to have Anthony Hopkins and Mel Gibson on the cover?

I came away from the project with a great admiration for William Bligh, who is surely one of the more grievously wronged-by-history men in the history of the British Empire.

Here's the introduction and about half of the (very long) first chapter of The Bounty Mutiny: From the Court Case to the Movie.

And, of course, a link to where you can buy it on Amazon!

***

Introduction

Boom!

The single cannon shot from HMS Duke rang out over the choppy gray water of England's Portsmouth Harbor. It was 8 A.M. on Wednesday, September 12, 1792, and the Duke had just hoisted a flag indicating that a court martial was in process.

Thirty minutes later, ten prisoners were led from the gun room of HMS Hector and loaded aboard one of the Hector's boats. British Marines in bright red uniform jackets stood at attention as the boat's crew dipped their oars and began the journey to the Duke, moored in the outer harbor.

More than an hour later, with the Marines still standing at attention, the boat reached the Duke. The prisoners were formally taken aboard, and then led into the captain's great cabin at the very stern of the ship to face the twelve captains who would serve as their judges and the Judge Advocate who would run the court. Also present were the prisoners' counselors, and various witnesses.

The Judge Advocate, Moses Greetham, began reading from the "Circumstantial letter" which laid out the details of the case: the ten men were accused of mutiny, a crime punishable by death.

Specifically, they were accused of the most famous mutiny of all time: the mutiny on His Majesty's Armed Vessel Bounty, the ship once commanded by Lieutenant William Bligh.

For more than two centuries now, that mutiny has captured the imagination of the world, inspiring histories, plays, novels, at least one stage musical, and five motion pictures.

Oddly enough, it all started with breadfruit.

Chapter 1: The Voyage of the Bounty

In 1688, while sailing around the world, a naturalist (and occasional pirate) named William Dampier noted an interesting new fruit from the island of Guam:

"The bread-fruit (as we call it) grows on a large tree…The fruit…is of a round shape and has a thick tough rind. When the fruit is ripe it is yellow and soft; and the taste is sweet and pleasant. The natives of this island use it for bread: they gather it when full grown while it is green and hard; then they bake it in an oven…the inside is soft, tender, and white."[i]

Later explorers, including Captain Cook (the first European to visit Hawaii and Australia) also extolled the virtues of the breadfruit. The fruit was so much like bread that sailors actually preferred it to their own bread. (That's not surprising, since the bread served in the middle of a long voyage was a kind of cracker made of flour, water, and salt known as "hardtack" or "ship's biscuit." Ship's biscuit was so hard it often had to be soaked before it could be eaten. It was also occasionally infested by the worm-like larvae of beetles.)

As early as 1775, the Society for West India Merchants saw the potential in breadfruit as a source of food for slave on the sugar plantations in the Caribbean. The Society offered a hundred pounds to the first person who could bring living breadfruit trees to England.

A Passion for Botany

Among those with businesses interests in the West Indies was Joseph Banks. Born in 1743, Banks was independently wealthy and passionately interested in natural history—particularly botany, the study of plants. When he was twenty-one he collected numerous never-before-seen specimens of plants along the coasts of Labrador and Newfoundland. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society, England's top scientific society, when he was just twenty-three.

He next joined Captain James Cook aboard the Endeavour when he set sail in August 1768 to carry British astronomers to Tahiti to observe the planet Venus crossing the disk of the sun.

The ship's visit to Tahiti seized the public's imagination upon the Endeavour's return to England in 1771, even though the island had first been reached by an English ship four years earlier. Banks had a lot to do with the public's sudden interest. He returned with thousands of specimens, drawings and paintings.

In 1778, after a final voyage to Iceland, Banks was elected president of the Royal Society. For decades, very few expeditions of science or exploration were undertaken without his consultation.

Banks wrote and received tens of thousands of letters from all over the world, full of questions and scientific observations. More than a few urged that the breadfruit tree be imported as a new food source for the West Indies.

Banks could see the fruit's potential. He convinced the British government to mount an official expedition, announced in February 1787, to bring back specimens of the plant.

A former merchant ship called the Bethia, approved by Banks, was purchased and renamed His Majesty's Armed Vessel (HMAV) Bounty. (The Bounty was too small to qualify for the designation His Majesty's Ship [HMS]).

Command of The Bounty was awarded to Lieutenant William Bligh.

Enter William Bligh

William Bligh, born September 9, 1754, was the son of Francis Bligh, customs officer at Plymouth, and Jane Pearce, a widow Francis had married just ten months earlier.

Reality vs. the Movie: A Cabin Boy at Age Seven?

Throughout this book, we'll be comparing real-life events to the way they were described or depicted in the 1984 movie The Bounty, produced by Dino de Laurentiis. In that movie, Bligh (Anthony Hopkins) tells Fletcher Christian (Mel Gibson) that he has been at sea since he was twelve.

In fact, William Bligh first appears in naval records as a ship's servant on the Monmouth at the age of seven—but it's unlikely he actually went to sea at that age.

In the 1700s, Royal Navy captains would often enter youngsters from well-connected families onto the books, providing them with valuable "sea time." Sea time was important because, to become a lieutenant, a young man had to appear on a ship's roster for six years, and serve as a midshipman or master's mate for at least two years of the six.[ii] Appearing on a ship's roster at a young age allowed the boy to step straight into a midshipman's position and take his lieutenant's exam sooner.

Bligh probably first went to sea for real at age sixteen, shortly after his mother died.

In 1770 Bligh signed on to the Hunter as an able seaman. This was a typical classification for potential officers on ships where all the positions for midshipmen—officers in training—were filled. Six months later a midshipman's position opened up, and Bligh was promoted.

From ages seventeen to twenty Bligh served as a midshipman on the Crescent, sailing to Tenerife and the West Indies. In 1774 he joined the Ranger, temporarily reduced to able seaman again, as she hunted smugglers in the Irish Sea.

At age twenty-one, Bligh learned that Captain Cook had selected him as sailing master of the Resolution for Cook's third expedition. Cook must have heard a good report of Bligh's navigational capabilities. He may also have known of Bligh's talent for drawing. Cook wanted all his officers to be able to construct charts and accurately sketch the various places in which the ship might anchor.[iii]

Sailing with Captain Cook

With Cook, Bligh sailed to Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania), New Zealand, Tahiti, and various Pacific islands. Cook also sailed up the west coast of North America in a failed search for the Northwest Passage (a more direct route from Europe to the Pacific that would avoid the stormy seas around Cape Horn, at the southern tip of South America).

Bligh must have paid close attention to Cook's methods for keeping his crew healthy on long voyages, because he later implemented some of those methods on the Bounty. Second to Cook himself, he was responsible for creating charts and surveys, and also drew accurate sketches of birds, animals, and landscapes.

On February 14, 1779, at Kealakekua Bay, Hawaii, Bligh witnessed the murder of Captain Cook by natives. In Bligh's view, the murder happened because the Marines guarding Cook did not do their duty.[iv] The tragedy affected Bligh not only personally but professionally. Bligh's family connections were just good enough to get him into the Navy as a midshipman, but he had been counting on Cook's influence to help further his career. (In the Royal Navy in that era, who you knew was often more important than what you knew.)

In February 1781, Bligh married Elizabeth Betham on the Isle of Man. After serving on a variety of ships for a few months near the end of the American Revolution, Bligh ended up on the Isle of Man with his wife and new daughter. In the scaled-back peacetime Navy, no officer's berths were available.

The peacetime Navy paid only two shillings a day, so Bligh had to find work. The Navy granted his request for permission to sail on merchant ships. From mid-1783 until he was appointed commander of the Bounty, he commanded ships belonging to his wife's wealthy uncle, Duncan Campbell, carrying goods from England to the West Indies and returning with rum and sugar.

His careful drawings and proven navigational skills probably recommended him to the Admiralty as commander of Sir Joseph Banks's breadfruit expedition. Navigational skills were important because, once he'd retrieved breadfruit from Tahiti, the Admiralty wanted him to chart the Endeavour Straits, a narrow, dangerous passage separating Australia (then called New Holland) and New Guinea).[v] Cook had run aground there. The Admiralty hoped Cook's sailing master might do better.

There's no evidence Banks ever met Bligh. But Bligh, knowing the career value of a powerful patron, thanked Banks profusely for command of the Bounty, and wrote: "I can only assure you I shall endeavour, and I hope succeed, in deserving such a trust…"[vi]

HMAV Bounty

The Bounty was a three-masted merchant vessel, built just 2 1/2 years earlier. She was 85 feet, 1 1/2 inches long on the upper deck and 24 feet 4 inches wide. At just 220 tons, she was much smaller than any of Cook's ships had been.

Because she was so small, she was rated as a cutter. That mattered because a cutter did not rate a captain or a commander as a commanding officer, but only a lieutenant. That, in turn, meant Bligh would not be getting a promotion, as he had hoped.

On a voyage expected to last at least two years, the difference between a lieutenant's and commander's pay was considerable. Bligh would earn just £70 a year. (As a merchant captain under Duncan Campbell, he'd been earning £500.) All the Navy offered was the assurance that that he would be promoted upon his return.[vii]

The Bounty was unusual in other ways, thanks to modifications Joseph Banks had insisted upon. All that mattered to Banks was the return of breadfruit, and, he wrote, "…the Master & Crew of her must not think it a grievance to give up the best part of her accommodations for that purpose."[viii]

The most notable modification from Bligh's point of view must have been the loss of the great cabin, the commanding officer's private quarters. Normally the great cabin was as wide as the ship and extended from the stern almost to the main mast, with windows on three sides providing plenty of light. But on the Bounty, the great cabin had been turned into a breadfruit nursery. It was filled with shelves, cut with holes to receive 629 pots. It had special ventilation, a stove for warmth, a drainage system that caught and recycled excess water, and more. Bligh had to make do with a windowless cabin, eight by seven feet. He would eat in a small, cramped pantry.

The Bounty's small size meant a smallish crew. Bligh would be the only commissioned officer. Warrant officers would include a master, boatswain, carpenter, gunner and surgeon. Bligh decided not to hire a purser, who normally bought provisions from the Navy Board, tracked them and doled them out on the voyage, and sold back unused ones at the end. Instead, Bligh would look after the disbursement of stores himself.

Most fatefully, the ship would not carry any Marines, who on most Navy ships served as the captain's security and police force.

CHAPTER ONE

[i] Dampier, William. A New Voyage Round the World. (London: Adam and Charles Black 1937.) < http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks05/0500... (January 17, 2008).

[ii] "Patronage and Promotion," Broadside – Home of Nelson's Navy. (January 18, 2007).

[iii] Alexander, Caroline. The Bounty. (New York: Penguin Group 2005). p. 44.

[iv] Ibid, p. 46

[v] Bligh, William and Christian, Edward. The Bounty Mutiny. (New York: Penguin Books, 2001.), p. 198

[vi] Hough, Richard. Captain Bligh & Mr. Christian: The Men and the Mutiny. (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1973). p. 64.

[vii] Ibid, p. 67

[viii] Alexander, p. 49

March 27, 2012

Test Drive: Ford Focus

Week before last Ford graciously provided me with the opportunity to drive a brand-new Ford Focus for a few days…which I found amusing for reasons that had nothing to do with the car. See, in my YA fantasy Song of the Sword, set here in Regina, one of the villains, who tries to abduct my young heroine, drives a Ford Focus. Which is not to say that only bad guys drive Ford Focuses (Focii?). But, you know, he had to drive something, and I just like the sound of the name: very alliterative.

Week before last Ford graciously provided me with the opportunity to drive a brand-new Ford Focus for a few days…which I found amusing for reasons that had nothing to do with the car. See, in my YA fantasy Song of the Sword, set here in Regina, one of the villains, who tries to abduct my young heroine, drives a Ford Focus. Which is not to say that only bad guys drive Ford Focuses (Focii?). But, you know, he had to drive something, and I just like the sound of the name: very alliterative.

Fortunately, my fictional bad guy's Focus was white, and this one was silver, so I didn't feel too much like I'd fallen into one of my own stories. Also, this one, unlike my character's, was the very latest model, and a high-end version, at that, with a terrific sound system and Ford's new MyFord Touch system.

The latter manifests itself as an eight-inch touch screen that pulls together in one location many of the controls that in the past would have been knobs or buttons (although some of those knobs and buttons are still around, since Ford provides redundancy). At first glance it all seems dangerously fiddly, but that, I soon found out, was because I was using it wrong (a few days later I had an in-car demonstration from a Ford expert on the system). The whole point of MyFord Touch isn't to get you to poke at a touch screen while driving, which obviously isn't the best of ideas, but rather to free you from having to poke at anything at all: pretty much everything on there can be controlled by voice, and the voice-recognition software is far more powerful than in most similar systems, recognizing some 10,000 words and phrases and even being able to interpret a comment like, "I'm hungry" and throw up (pardon the expression) a list of nearby restaurants.

Ford actually wants you to keep your eyes on the road, not on the dashboard, and once you get the hang of the MyFord Touch system, that's exactly what you can do. (Although, being who I am, I kept thinking of that song from Paint Your Wagon, "I talk to the trees…" with updated lyrics: "I talk to my car, but it never listens to me…" With MyFord Touch, that shouldn't be a problem.

Ford actually wants you to keep your eyes on the road, not on the dashboard, and once you get the hang of the MyFord Touch system, that's exactly what you can do. (Although, being who I am, I kept thinking of that song from Paint Your Wagon, "I talk to the trees…" with updated lyrics: "I talk to my car, but it never listens to me…" With MyFord Touch, that shouldn't be a problem.

Better yet, the MyFord Touch system is software, not hardware: which means, when Ford decides to update (as it has already done), it can simply send out to customers a USB stick with the new software on it. Plug it in, in within 45 minutes or so your car is up to date. (I believe the Focus I was driving had the original software in it; the example I was shown later with the new software looked a bit different from what you see in the photo).

Something else I noticed on the Focus that I hadn't noticed on last year's vehicles was a path indicator in the rear-view camera display that comes on automatically when you go into reverse. In other words, it not only shows you what's behind you, it shows you where the edges and center of the car will travel as you turn the wheel during your backward adventures. Very useful.

Driving-wise, I found the car nimble, especially compared to my 2002 Volvo S60, which I love, don't get me wrong, but which has the turning radius of a small truck. Or maybe a large truck. Acceleration was not all I would have liked it to be, since I crave power, power and more power! (Oops, sorry. Let my internal villainous monologue show there for a moment.) But it was certainly acceptable, especially in a car of this size and class.

My wife and I both liked the styling. It's a good-looking vehicle, no question about that, and if it won't turn a lot of heads in your direction as you drive down the street, it won't turn heads away from you in horror, either. The interior looks sharp, too. Our only negative comment was the seats, which we both found a bit firm for our taste. But our aforementioned Volvo is renowned for having comfortable seats, so we seldom find anything we like better.

My wife and I both liked the styling. It's a good-looking vehicle, no question about that, and if it won't turn a lot of heads in your direction as you drive down the street, it won't turn heads away from you in horror, either. The interior looks sharp, too. Our only negative comment was the seats, which we both found a bit firm for our taste. But our aforementioned Volvo is renowned for having comfortable seats, so we seldom find anything we like better.

All in all, an excellent entry into Ford's parade of cars. And, no, you don't have to be the villain in one of my books to drive one. You just need to be someone in search of a good-looking, well-put-together fun-to-drive (and fuel-efficient!) small car.

And if you do happen to be a fictional villain, well, what could be better than a car you can literally give orders to? It's kind of like your personal henchman.

March 26, 2012

Pop! goes nutrition

There's nothing quite like the smell of popcorn. It makes you think of movie theatres, the circus, the midway. It makes you long for a handful. Or two. Or better yet, a whole bucket.

There's nothing quite like the smell of popcorn. It makes you think of movie theatres, the circus, the midway. It makes you long for a handful. Or two. Or better yet, a whole bucket.

And best of all, just this week some research results were released that indicate popcorn is also a very healthy food!

I'll get to that in a minute, but first, some background.

Nobody knows who first popped popcorn, which is thought to have originated in Mexico. Ears found in the Bat Cave of West Central New Mexico were dated to some 5,600 years ago, and 1,000-year-old grains of popcorn found in tombs along the east coast of Peru were so well-preserved they could still be popped.

By 1492, when Columbus sailed the ocean blue, popcorn was widespread in the Americas. English settlers were introduced to it at the famous first Thanksgiving feast in Plymouth, Massachusetts, to which Quadequina, brother of the Wampanoag chief Massasoit, reportedly brought a deerskin bag full of popped corn.

Popcorn kernels pop due to water stored inside a layer of soft starch beneath a hard outer casing. Heat the popcorn up to about 230 degrees Celsius and that water turns to steam, which creates so much pressure that the casing gives away. The kernel explodes, turning inside out, the starchy layer beneath the casing becoming the fluffy white confection we like to eat.

And perhaps we should be eating more of it. At the 243rd National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society, Joe Vinson of the University of Scranton in Pennsylvania and his colleagues reported on a new study that found that the healthy antioxidants known as polyphenols are actually more plentiful in popcorn than in fruits and vegetables.

That's because, Vinson says, popcorn averages only four percent water, while fruits and vegetables are 90 percent water, which dilutes the polyphenols. (Dried fruits have more polyphenols per serving than fresh fruit for the same reason.) Popcorn provides levels of polyphenols similar to those in nuts.

The highest concentration of polyphenols and fiber is actually in the hull, which isn't exactly everyone's favorite part of the popcorn, but perhaps the fact they're, as Vinson calls them, "nutritional gold nuggets," will make you feel better about having them stuck in your teeth. Thanks to that hull, popcorn is also the only snack that is 100 percent unprocessed whole grain, far better than your typical "whole grain" cereal, which only has to be 51 percent whole grain to qualify for that title.