Edward Willett's Blog, page 51

August 24, 2012

Usain Bolt? He’s not so fast

OK, admittedly the title of this column is a bit tongue in cheek. Compared to, well, any other human being on the planet, Usain Bolt is, of course, insanely fast. (I have not personally compared my speed in the 100-metre dash with his, of course, but since I’d have to stop halfway to be loaded onto an ambulance I suspect I’d have little hope of matching him.)

OK, admittedly the title of this column is a bit tongue in cheek. Compared to, well, any other human being on the planet, Usain Bolt is, of course, insanely fast. (I have not personally compared my speed in the 100-metre dash with his, of course, but since I’d have to stop halfway to be loaded onto an ambulance I suspect I’d have little hope of matching him.)

But compared to the rest of the animal kingdom, Usain Bolt…or any other human…is small potatoes.

In an article entitled “Animal athletes: a performance view,” the July 28 issue of Veterinary Record did the comparison, finding Bolt would trail greyhounds, cheetahs and pronghorn antelopes, among others.

Not only that, many animals beat us for strength, too.

According to Craig Sharp from the Centre for Sports Medicine and Human Performance at Brunel University, humans can run at a maximum speed of 23.4 miles per hour (37.6 kilometres/hour) or 10.4 metres per second. On the plus side, that means a fast human can outrace a dromedary…but only just; dromedaries’ top speed is 22 mph (35.3 kph), or 9.8 metres/second.

But when it comes to cheetahs, we’re not even close. A cheetah is twice as fast as an Olympic-level sprinter, able to cover ground at 64 mph (104 kph) or 29 metres/second.

And the aforementioned pronghorn antelope? He’s going to leave poor old Bolt in the dust, too, bounding away at 55 mph (89 kph) or 24.6 metres/second.

They’re not alone. The North African ostrich, Sharp notes, runs at 40 mph (64kph) or 18 metres/second, making it the fastest running bird. In the water, the record belongs to the sailfish, which can swim an astonishing 67 mph (108 kph) or 30 metres/second. Take that, Michael Phelps!

Racehorses are no slouches, either. The fastest thoroughbred has managed 55 mph (88 kph). And greyhounds, synonymous with speed among canines, cover ground at 43 mph (69kph).

It’s perhaps unfair to include flying birds, since humans can’t fly, but still, it’s worth noting their impressive achievements in the air: peregrine falcons can reach speeds of 161 mph (259 kph), while even the ubiquitous ducks and geese can reach 64 mph (103 kph) in level flight.

On the power side of the ledger, you might think birds would be pretty weak…but you’d be wrong. Flying requires a lot of energy, and pheasant and grouse, to name just two, can generate 400 Watts per kilo from their wing muscles—five times as powerful as trained athletes. Even hummingbirds, tiny though they might be, can manage 200W/kg.

Strength? Even those massive Olympic weightlifters wouldn’t stand a chance in an all-species Olympics. The African elephant can lift 300 kg with its trunk and carry 820 kg. A grizzly bear can lift 455 kg. And gorillas? 900 kg.

Sharp admits that humans have adapted remarkably well to long-distance running, thanks to long legs, short toes, arched feet, and ample fuel storage capacity. But camels can trot at 10 mph (16 kph) for more thanr 18 hours. And then there are Siberian huskies: in 2011, a team raced for eight days, 19 hours, and 47 minutes, covering 114 miles a day.

Some specific comparisons Sharp makes:

Usain Bolt ran the100 metres in 9.58 seconds; a cheetah ran the same distance in 5.8 seconds.

Usain Bolt ran 200 metres in 19.19 seconds; a cheetah covered the same distance in 6.9 seconds, Black Caviar (a racehorse) in 9.98 seconds, and a greyhound in 11.2 seconds.

Michael Johnson ran the 400 metres in 43.18 seconds, compared with 19.2 seconds for a racehorse and 21.4 seconds for a greyhound

David Rushida ran 800 metres in one minute 41 seconds, compared with 33 seconds for the pronghorn antelope and 49.2 seconds for a greyhound.

An endurance horse ran a full marathon in one hour 18 minutes and 29 seconds, compared with the two hours, three minutes and 38 seconds of Patrick Makau Musyoki.

In the long jump, a red kangaroo has leapt 12.8 metres, compared to the 8.95 metres Mike Powell achieved. Its high jump of 3.1 metres exceeds Javier Sotomayor’s of 2.45. Sotomayor is even outdone by the lowly snakehead fish, which can leap four metres out of the water

But don’t let all this get you down. Remember, there’s one thing no animal has ever managed to do: deliberately throw a badminton match.

For that, you need a human.

A Wordle for Masks

Here’s a Wordle for my upcoming YA fantasy novel Masks, to be published by DAW Books under the pseudonym E.C. Blake (publication date coming soon!). Mara, as you might guess, is the name of the main character.

August 18, 2012

Saturday Special: Careers in Outer Space

Careers in Outer Space is woefully out of date now, having come out ten years ago, but it’s notable in that it’s the first of several books I did for Rosen Publishers (I haven’t done one for a while, but I hope to do more in the future). Also, of course, it was on a topic near and dear to my science-fictiony heart: space travel.

Careers in Outer Space is woefully out of date now, having come out ten years ago, but it’s notable in that it’s the first of several books I did for Rosen Publishers (I haven’t done one for a while, but I hope to do more in the future). Also, of course, it was on a topic near and dear to my science-fictiony heart: space travel.

Another interesting side note: the reason I ended up doing this book was because I had read that Josepha Sherman was editing at Rosen. I contacted her because I kind of knew her: she had been editing at Walker & Co. back in the early 1990s, where I had sent her my YA SF novel The Minstrel (based on the short story I posted here a few weeks ago). She had responded saying she couldn’t take it as is but would be happy to look at it again if I wanted to make some revisions. Naturally, I made some revisions, and sent it back. And then…(sigh)…as she explained in public during a panel at the WorldCon in Winnipeg in 1994, I’d done just what the book needed and she was “ready to make an offer”…only the publisher died, and the new publisher decided Walker was getting out of publishing science fiction. And so The Minstrel went back into the trunk and still hasn’t found a publisher to this day (although if nothing else I will undoubtedly revise it and bring it out as an ebook some day).

Still, perhaps that connection helped, and Josepha offered me Careers in Outer Space, which I was glad to take on. She left Rosen very shortly thereafter, alas.

Although the book as a whole is dated, the intro and the first chapter, featuring a very brief history of spaceflight, are still pretty good. Enjoy!

***

Careers in Outer Space

By Edward Willett

Introduction

“Space: the final frontier.” The famous opening words of Star Trek are more than just a great way to start a television show–they’re also an accurate description of what lies beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

Space really is the final frontier. Most of Earth has been explored and mapped; people live just about everywhere it’s possible for people to live. But beyond Earth there’s a whole universe to study, explore–and even colonize.

In fact, we’ve already begun. Today thousands of men and women work in fields that are related to the exploration of space. A lucky few are astronauts, the ones who actually travel into space. Many more work on the ground, building the rockets that take the astronauts into space, designing satellites to study space–and the Earth from space–or training delicate instruments on the farthest reaches of the universe to learn everything they can about what’s out there.

Very few people will ever travel into space. Maybe you’ll be one of them. But even if you’re not, if you’re interested in space, you can find a career that will let you pursue your passion without ever leaving the ground.

Chapter 1: A Brief History of Space Exploration

Space exploration didn’t begin with the launch of the first man into space. In a sense, it began the first time some unknown ancient human looked up at the stars and wondered what they were.

The ancient Greeks spent a lot of time wondering about the universe and how it was put together. Aristotle, who lived from 384 to 322 B.C., developed the common idea that the Earth was the center of the universe, and everyone pretty much accepted that for centuries to come–until 1543, in fact. That’s when a Polish astronomer, Nicolas Copernicus, published a book suggesting that the Earth (and the other planets) go around the sun, instead of the other way around. More than 60 years later, a German astronomer, Johannes Kepler, published another book demonstrating mathematically that the planets did in fact circle the sun.

At about the same time, the first telescopes were invented, and in 1632, Galileo Galilei, one of the first astronomers to use the telescope in his work, published his evidence for Copernicus’s idea. The Roman Catholic church was not amused, because Galileo’s work seemed to contradict the Bible, and so the church forced Galileo to withdraw his statements.

But Galileo was right, of course, and in 1687 Isaac Newton published a very famous book called Principia, which explained how gravity holds the universe together.

With that basic understanding of the universe in place, astronomers began to learn more and more about the stars and planets that filled it. Writers like Jules Verne, who wrote From the Earth to the Moon in 1865, even began to imagine traveling in space.

But the 20th century was to be the one in which humans were finally able to send machines and eventually themselves into space. Russia’s Konstantin Tsolikovsky put forward the idea of using liquid-fueled rockets in space travel in 1903, and in the 1920s, the American Robert Goddard conducted experiments with liquid-fuelled rockets that proved Tsolikovsky was on to something.

The Second World War brought great advances in rocket technology, culminating in the V-2, which Nazi Germany used to bombard London. After the War, many of the German scientists ended up in the Soviet Union and the United States, where they continued their research, beginning with captured V-2 rockets.

Then, in 1957, the Soviet Union put the first satellite, Sputnik 1, into orbit, followed shortly by the first animal, a dog named Laika. The United States tried frantically to catch up, but suffered a series of embarrassing launch failures before finally launching its own satellite, Explorer 1, in 1958.

The two countries, who were already rivals in international politics, became locked in a race to see who could outdo the other in space. The Soviet Union got off to a head start by launching the first man, Yuri Gagarin, into orbit in 1961. The U.S.’s first astronaut into space (though he didn’t go into orbit) was Alan Shepard, later that same year; and then President John F. Kennedy upped the stakes by proclaiming the goal of putting a man on the moon by the end of the decade.

The U.S. succeeded in doing just that; Neil Armstrong, commander of Apollo 11, became the first man to set foot on the moon on July 20, 1969. In all, six Apollo missions landed on the moon over the next three years.

After that, the focus shifted to Earth orbit for manned space flight; but robots, which had already traveled to Mars and other planets in the 1960s, were sent to the farthest reaches of the solar system. The U.S.’s Viking 1 and Viking 2 landed on Mars in 1976 and the Voyager and Pioneer spacecraft sent back fantastic pictures of Jupiter, Saturn and other distant planets.

The first space shuttle was launched in 1981; five years later, the space shuttle Challenger exploded less than two minutes after launch, killing all seven crew members. For a time there were no shuttle launches, but in the 1990s shuttle flights have once again come to seem almost routine, taking place every few months to launch satellites and conduct experiments–and, in the past few years, to begin construction of the International Space Station, the current focus of manned space flight.

Meanwhile, here on Earth astronomers continue to make astounding discoveries about the universe, using tools ranging from giant radio telescopes on the ground to the Hubble Space Telescope, an orbiting observatory that provides images far more detailed than any Earth-based telescope can manage.

Robots, too, continue to explore the solar system, even landing and roving around Mars–the planet which many people would like to see humans land on within the next 20 or 30 years.

And just as the American West went from being wild to being civilized and citified, so space is beginning to attract, not only explorers, but people who see it as a place of opportunity. Today there are telecommunications companies that launch and own their own satellites, companies with plans for hotels in space, even a company that hopes to launch its own roving robot to the moon.

All of these programs require talented, skilled and dedicated people. In the pages of this book, you’ll learn about many different space-related careers–and what you can do now to begin working toward a life in this exciting, fascinating field.

Important dates in space

March 16, 1926 — Robert Goddard launches the world’s first successful liquid-fueled rocket, in Auburn, Massachusetts.

October 3, 1942 – The first German V-2 rocket is successfully launched.

1946 – The U.S. and the Soviet Union begin their space research programs by experimenting with captured German V-2s–with the help of captured German rocket scientists.

April, 1955 – The Soviet Union announces plans to explore the moon and devise an Earth-orbiting satellite.

July 29, 1955 – President Dwight D. Eisenhower announces plans to launch U.S. satellites.

October 4, 1957 – The Soviets launch the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1.

November 4, 1957 – The Soviets launch Sputnik 2, carrying a dog, Laika, the first animal to orbit the Earth.

January 31, 1958 – The U.S. launches its first satellite, Explorer 1.

October 1, 1958 – The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) begins operation.

January 2, 1959 – The Soviets launch the Luna 1 space probe, the first human-made object to fly past the moon. A follow-up probe crash-lands on the moon; another sends back pictures of the moon’s far side.

April 9, 1959 – The U.S. introduces its first seven astronauts.

April 12, 1961 – Soviet Yuri Gagarin is the first person in space, orbiting the Earth in a 108-minute flight.

May 5, 1961 – Astronaut Alan Shepard is the first American in space, completing a 15-minute suborbital flight.

Feb. 20, 1962 – John Glenn is the first American to orbit Earth.

June 16, 1963 – Soviet Valentina Tereshkova is the first woman in space, orbiting Earth in Vostok 6.

March 18, 1965 – Soviet Alexei Leonov is the first person to walk in space.

June 3, 1965 – Ed White makes the first U.S. space walk.

July 14, 1965 – The U.S. probe Mariner 4 transmits the first close-range images of Mars back to Earth.

February 3, 1966 – The Soviet Luna 9 probe makes the first soft landing on the moon.

June 2, 1966 – The U.S. Surveyor 1 probe lands on the moon.

January 27, 1967 – Astronauts Virgil “Gus” Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee are killed during a test of Apollo 1.

April 24, 1967 – Soviet Vladimir Komarov dies when Soyuz 1 crashes during re-entry.

December 21, 1968 – The Apollo 8 crew, Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders, are the first humans to orbit the moon.

July 20, 1969 – Astronaut Neil Armstrong of Apollo 11 becomes the first person to walk on the moon.

April 11, 1970 – The crew of Apollo 13 narrowly escapes death after an explosion.

April 19, 1971 – The Salyut 1 space station is launched by the Soviets. Its first team of cosmonauts dies during re-entry in June.

December 2, 1971 – The Soviet Union’s Mars 3 makes the first soft landing on Mars.

December 7, 1972 – Apollo 17 becomes the last mission to visit the Moon to date.

May 14, 1973 – Skylab, America’s first space station, is launched. It remains in orbit for six years.

July 17, 1975 – Apollo 18 and Soyuz 19 dock in space, the first international collaboration.

July 20, 1976 – The U.S. Viking 1 orbits Mars and lands a craft on its surface that conducts soil analysis. Viking 2 repeats the feat in September.

February 18, 1977 – NASA begins testing the space shuttle.

April 12, 1981 – John Young and Robert Crippen fly the first space shuttle, Columbia, into orbit.

November 12, 1981 – Columbia’s second flight marks the first time any spacecraft has returned to space.

June 13, 1983 – The Pioneer 10 space probe becomes the first manmade object to leave the solar system.

June 18, 1983 – Sally Ride is the first U.S. woman in space.

August 30, 1983 – Guion Bluford is the first African-American astronaut to fly in space.

February 7, 1984 – Bruce McCandless takes the first untethered space walk.

January 28, 1986 – Space shuttle Challenger explodes after launch, killing its crew.

February 20, 1986 – The Soviets launch the core of their Mir space station.

September 29, 1988 – The first space shuttle since the Challenger disaster is launched.

April 25, 1990 – The shuttle deploys the Hubble Space Telescope. Its mirror proves to be faulty.

December 4-10, 1993 – Astronauts capture and repair the Hubble Space Telescope.

February 3, 1994 – Cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev is the first Russian to be launched in a U.S. space shuttle.

March 14, 1995 – Norman Thagard is first American to be launched on a Russian rocket.

March 25, 1995 – Cosmonaut Valery Polyakov sets a space-endurance record of 437 days, 18 hours aboard Mir.

September 7, 1996 – American Shannon Lucid sets an endurance record for women in space with a 188-day mission aboard Mir.

June 25, 1997 – The U.S. Sojourner Rover becomes the first vehicle to roam Mars.

October 29, 1998 – John Glenn, 77, is the oldest person to visit space, 36 years after his first flight.

November 20, 1998 – Russia launches Zarya, the first element of the International Space Station.

December 4, 1998 – The first U.S. module of the International Space Station, Unity, is attached to Zarya.

November 2, 2000 – The first permanent crew boards the International Space Station.

March 23, 2001 – The 15-year-old Russian space station Mir returns to Earth in a controlled descent, splashing into the Pacific Ocean.

April 28, 2001 – American Dennis Tito is the first space tourist, paying the Russian government $20 million for a six-day trip to the International Space Station.

August 4, 2012

From small-town hockey player to Broadway star: Paul Nolan’s improbable journey

This week’s Saturday Special is the interview I conducted with Paul Nolan, who grew up in the small town of Rouleau, just outside Regina (better known, perhaps, as Dog River from the TV series

Corner Gas

), and just ended a run on Broadway in the title role of the revival of

Jesus Christ Superstar

(he’s now starring in a production of the Elton John version of

Aida

in Kansas City, but

JSC

was still running when I wrote this story for

Fine Lifestyles

magazines.)

This week’s Saturday Special is the interview I conducted with Paul Nolan, who grew up in the small town of Rouleau, just outside Regina (better known, perhaps, as Dog River from the TV series

Corner Gas

), and just ended a run on Broadway in the title role of the revival of

Jesus Christ Superstar

(he’s now starring in a production of the Elton John version of

Aida

in Kansas City, but

JSC

was still running when I wrote this story for

Fine Lifestyles

magazines.)

I performed with Paul many times when he was growing up, and once since, when I was in Persephone Theatre‘s production of Beauty & the Beast in 2007, in which he played the Beast. He’s a tremendous performer and a fabulous singer, and it’s great to see him having such success.

Enjoy!

***

By Edward Willett

It’s a long, strange journey from small-town hockey player to Broadway musical theatre star, a journey so unlikely it’s probably safe to say Roleau native Paul Nolan is the only one who has ever made it.

But make it he has: the 33-year-old is currently starring as Jesus in the Tony-nominated revival of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s classic rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar in the Neil Simon Theatre in New York City.

He’s garnered rave reviews for it, too. There have been articles in The New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, The New Yorker and Vanity Fair. The Associated Press called him “all-around excellent.” The Globe & Mail wrote, “With his hypnotic performance as Jesus, Paul Nolan remains the show’s superstar.”

And, he says, “It all began with voice lessons.”

From hockey to music

The youngest of five children (he has four older sisters), Nolan grew up in a farming family. Like most prairie boys, his first focus was hockey. “I started playing when I was six. We happened to have a very talented group of guys. Before I left hockey for good at age 17 we had won two provincial championships, and they won another after that.”

But even though he enjoyed hockey and was good at it, it wasn’t until he began voice lessons with Betty Hayes, who introduced him to Regina’s artistic circles, that he found what he calls “my community.”

Then came another revelation: a touring production of Les Miserables Nolan saw at the Saskatchewan Centre of the Arts when he was 13 or 14. “From that night forward, I knew that was what I wanted to do with my life.”

He began with local productions, performing with Regina Summer Stage and Regina Lyric Light Opera, and continued voice lessons, first with Hayes, then with Robert Ursan.

“I doubt I would be where I am today having not studied with Rob as a voice teacher,” Nolan says. “He and Betty are the reason I have any technique and can do this eight times a week.”

Nolan also joined Do It With Class Young People’s Theatre Co. “It was another affirmation that there was a community for me. In a town of 500 people, the focus is not very often put on the arts. It’s almost always sports. If you don’t fit into that peer group, it can be a struggle. DIWC was an affirmation, and very responsible for my success.”

Second thoughts

Nolan moved to Toronto after high school, and attended the Randolph Academy, a musical theatre school, which is where he started his professional work. And hasn’t looked back since…

…well, except maybe once.

“Even now, with the success I’m having, I still kind of fantasize about a more stable life,” Nolan admits, and in 2004 he actually left the business for a year. “I did volunteer work at a children’s camp in St. Lucia for all of August and worked on the family farm. I travelled. I was serious about not working any more as an actor. I really wanted to make a different life.”

But in 2005 he returned to the stage. The role? Jesus in a production of Jesus Christ Superstar at the Sunshine Festival in Orillia.

That was followed by five seasons at the Stratford Festival…and the first steps toward Broadway.

In Nolan’s second year at Stratford Tony-award winning director Des McAnuff became artistic director. In his first meeting with McAnuff, Nolan recalls, “I did a monologue—I don’t think I sang—and we talked for five or ten minutes. He asked me what I would I like to do. I told him, ‘I want to play Jesus in Jesus Christ Superstar in this Festival.’”

Just recently McAnuff revealed to Nolan that that comment helped spark the new production. “He doesn’t normally think actors cast themselves well in roles,” Nolan marvels, “but he didn’t even audition me for it. He asked me to play Jesus before my first preview as Orlando in As You Like It. He approached me in the staircase and said, off the cuff, ‘I want you to play Jesus in Superstar next year.’ I was kind of dumfounded and blindsided. It was a dream role.”

And, he adds, with a laugh, “It was one of the first times I haven’t auditioned for a role. I could get used to that!”

A sizeable Saskatchewan contingent

After a smashing success in Stratford, the show moved to the La Jolla Playhouse in California, and then to Broadway.

It brought a larger Saskatchewan contingent than just Nolan to the Great White Way. The Stratford production had six Saskatchewanians: Jacqueline Burtney (daughter of Andorlie Hillstrom, artistic director of Do It With Class), Matt Alfono and Kyle Golemba (both also DIWC alumni), Stephen Patterson and Mary Antonini. Golemba and Patterson decided to stay in Stratford for this season, but the others are in New York with Nolan.

“There are a lot of Saskatchewan people at the Stratford Festival,” Nolan notes. “They say the cold winters force us to be creative.” More seriously, he says, Saskatchewan offers extraordinary support for its arts community, and particularly for young people in the arts.

So is it overwhelming for a small-town prairie boy to perform on one of the storied stages of Broadway?

Nolan laughs. “I think my family keeps me grounded,” he says. “They’re very, very, very proud, but I think they would be very quick to slap me in the side of the head if I was getting carried away with my own ego.”

He admits, though, that, “If it had happened earlier, maybe I wouldn’t have been so grounded. I know who I am a lot more than I did when I was 23 or 24.”

He tries to look past the Broadway myth. Stratford, he notes, though it may lack the cachet of Broadway, is “creating artists, and nurturing artists, and creating great internationally groundbreaking work and nourishing the thirst of actors to deal with a classical text.”

Ultimately, he says, “It isn’t our job to create the myth, it’s our job to create the art, to do a great job that we believe in. Being an artist, you tend to go where your artistic thirst is quenched. Right now it’s in Jesus Christ Superstar.”

An ever-evolving role

Even though he’s been playing Jesus for months, he finds that his understanding of the role continues to get “richer and richer and richer.”

Each performance is slightly different. “Sometimes I’m exhausted, energetic, sorrowful, joyful, hopeful, defeated—all of those things would have applied to Jesus Christ. He was an incredibly dualistic person, as many and most humans probably are. I find that wonderful to play. It leaves it open to be almost anything.

“Sometimes I’m out there and I’m thinking, ‘This can’t possibly be Jesus, I’m too angry,’ or, ‘I’m too happy,’ but all of that is Jesus. Over time I just have allowed myself to be anything. For me I know where it comes from,” (what he calls the “seed” of the role), “and there’s where I start my night.”

When he’s not on stage, what does he do for fun in the greatest city in the world?

Play softball, what else? Every Thursday for an hour and a half, in the Broadway Softball League. Other than that, “I spend a lot of time having to prepare—getting physical therapy that helps me do it over and over and over again.”

He did find time to visit Yankee Stadium. He was to sing “God Bless America” during the seventh-inning stretch of the Yankees’ home opener.

Nolan is committed to playing Jesus until mid-September, if the show runs that long, and would love to continue for another six months after that. Eventually, though, his time as Jesus will come to an end. And then?

He cheerfully admits he doesn’t have a clue. “I’ll eventually sort that out,” he says, then adds with considerable understatement, “This is big enough right now.”

Let’s go to the tape

While I was browsing for another Olympic-themed column idea (as promised last week) one story particularly caught my eye: a Reuters piece by Kate Kelland headlined (in the Regina LeaderPost, at least) “Scientists skeptical as Olympic athletes get all taped up.”

While I was browsing for another Olympic-themed column idea (as promised last week) one story particularly caught my eye: a Reuters piece by Kate Kelland headlined (in the Regina LeaderPost, at least) “Scientists skeptical as Olympic athletes get all taped up.”

It caught my eye, not because it had a picture of female beach volleyball players in bikinis attached to it (honest!), but because I had seen, on the backs of some of the synchronized divers a few days ago, these weird pieces of colored tape…and I had no idea what they were.

Turns out they’re Kinesio tape, and it’s not new, as I has assumed: in fact, it’s been around since the 1970s, which is when it was developed by Dr. Kenzo Kase, a Japanese chiropractor and acupuncturist. However, its popularity has soared as more and more elite athletes have begun using it. (A donation of 50,000 rolls to Olympic athletes in the 2008 games in Beijing no doubt helped.)

According to the Kinesio company website, Dr. Kase developed the tape, which has a texture and elasticity close to that of living human skin, because he found standard taping techniques too restrictive for his patients. Specifically, the website claims, Kinesio tape can be used to “re-educate the neuromuscular system, reduce pain, optimize performance, prevent injury, and promote improved circulation and healing.”

Apparently it can only do those things if applied properly, though, which is why Kinesio taping is taught through a special training course. In Britain alone, the Reuters story notes, there are currently 4,000 people trained in Kinesio taping.

So, it’s popular, it’s becoming ubiquitous, and elite athletes swear by it. But does it actually, you know, work?

According to Kelland, there has been little rigorous scientific research on Kinesio tape, but the handful of papers that have been published indicate its ability to relieve pain or improve muscle strength is actually limited.

A review of all the scientific research on the tape thus far, published in Sports Medicine journal in February, found “little quality evidence to support the use of Kinesio tape over other types of elastic taping in the management or prevention of sports injuries.”

The company responds to that by saying that research hasn’t simply caught up with the benefits users are reporting. And lots of users there are. For example, Ilka Semmler of the German beach volleyball team was sporting pink strips of tape on her buttocks in the photo accompanying the Reuters piece (the one that had nothing to do with why this story caught my eye).

Swedish handball player Johanna Wiberg wears blue tape from knee to groin. British sprinter Dwain Chambers has been known to wear it in a Union Jack design. And then there were those divers that first made me wonder about the tape: they mostly wore it in pink, in two strips on the small of the back.

The reason some scientists question the tape’s efficacy is the reason us skeptical types always question stuff like this: they’re not convinced by the underlying mechanism, which in this case is the supposed “lifting” ability of tape applied to the skin to enhance the performance of muscles deep inside the body.

Steve Harridge, a professor of human and applied physicology at King’s College London, is quoted in the Reuters article as saying, “It may be a fashion accessory, and it may just be one of those fads that come along from time to time, but to my knowledge there’s no firm scientific evidence to suggest it will enhance muscle performance.”

But both he and John Brewer, a professor of sports science at Britain’s University of Bedfordshire, who is also quoted in the article and is equally doubtful about the tape’s claims, say in effect that it doesn’t matter what they think: what matters is what the athletes think.

Like people in drug trials who find their symptoms improve even though they’re actually taking sugar pills, an effective placebo in elite athletics “could make all the difference between success and failure.”

So don’t laugh too much at those weird pieces of tape. Scientifically, they may not really be doing what the athlete thinks they’re doing…but if the athlete thinks they are doing it, then maybe, in fact, they are.

I’m glad I could clear that up.

(The photo: Brazil’s Juliana spikes the ball as Germany’s Ilka Semmler (L) blocks it during their women’s preliminary round beach volleyball match at the London 2012 Olympic Games at Horse Guards Parade July 30, 2012. – Marcelo Del Pozo, REUTERS.)

July 29, 2012

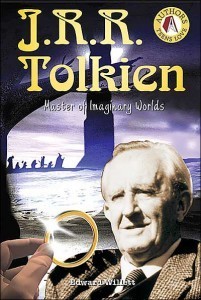

Saturday (er, Sunday) Special: J.R.R. Tolkien, Master of Imaginary Worlds

I think I’ve now posted the introductions to all of the biographies I wrote for Enslow Publishers except this one:

J.R.R. Tolkien, Master of Imaginary Worlds

. Like my book on Orson Scott Card, it was part of their Authors Teens Love series.

I think I’ve now posted the introductions to all of the biographies I wrote for Enslow Publishers except this one:

J.R.R. Tolkien, Master of Imaginary Worlds

. Like my book on Orson Scott Card, it was part of their Authors Teens Love series.

Why, yes, I did really really enjoy writing this one. How did you guess?

***

J.R.R. Tolkien: Master of Imaginary Worlds

By Edward Willett

Introduction

The world might never have heard of J.R.R. Tolkien, or The Lord of the Rings, if not for two young people. One was an anonymous student. The other was the son of an English publisher.

The anonymous student delighted Tolkien by leaving a blank page in his School Certificate paper. One year in the late 1920s or early 1930s (Tolkien couldn’t remember exactly), Tolkien was marking School Certificate Papers in his home in Northmoor Road, Oxford.[i] (School Certificate Papers were exams given to high school students who wanted to attend one of the colleges.)

This wasn’t part of Tolkien’s duties as Professor of Anglo-Saxon at the University of Oxford. It was really a summer job, a way to bring in a little extra money between school terms. [ii] It was also terribly boring. In a letter to W.H. Auden years later, Tolkien wrote of “the everlasting weariness of that annual task forced on impecunious (poor) academics with children.”[iii]

But then he turned over one page to find, “One of the candidates had mercifully left one of the pages with no writing on it (which is the best thing that can possibly happen to an examiner) and I wrote on it: ‘In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.’”[iv]

That single, simple sentence was like a seed that eventually sprouted into The Hobbit. From The Hobbit, years later, grew The Lord of the Rings.

“Names always generate a story in my mind,” Tolkien said. “Eventually I thought I’d better find out what hobbits were like.”[v]

Tolkien’s first attempt to turn his single sentence into a complete novel didn’t get past the first chapter. He put the manuscript aside for years, then began again. He read chapters to his children after tea on winter evenings. But he still didn’t finish the story.[vi] In fact, he abandoned it shortly after the death of the dragon Smaug, late in the book. He’d occasionally show the manuscript to friends like C.S. Lewis (author of The Chronicles of Narnia), but mostly it sat in his study, unfinished and likely to remain so.[vii]

But one of the people who did see it was an Oxford graduate named Elaine Griffiths. On Tolkien’s recommendation, Griffiths, a former student of his, had been hired by the London publishers George Allen & Unwin. In 1936 Griffiths mentioned to a friend of hers, Susan Dagnall, a member of the publisher’s staff, that Tolkien had a wonderful unfinished children’s story. Dagnall asked Tolkien for a copy, and took it back to London. She liked it, and asked Tolkien to finish it. He took up the story again, and in October sent the completed manuscript to George Allan & Unwin.

Stanley Unwin, chairman of George Allen & Unwin, thought that the best judges of children’s literature were children themselves, so he gave the manuscript to his son Rayner, age 11.[viii] Rayner read it and wrote a short review of it for his father, who paid him one shilling for his work. Rayner liked the book, so his father published it in the fall of 1937.

Begin SIDEBAR

Rayner Unwin ‘s book report on The Hobbit

Here’s the report (complete with the original spelling) that Rayner Unwin wrote about The Hobbit for his father, Stanley Unwin:

“Bilbo Baggins was a hobbit who lived in his hobbit-hole and never went for adventures, at last Gandalf the wizard and his dwarves perswaded him to go. He had a very exciting time fighting goblins and wargs, at last they got to the lonley mountain; Smaug, the dragon who gawreds it is killed and after a terrific battle with the goblins he returned home–rich! This book, with the help of maps, does not need any illustrations it is good and should appeal to all children between the ages of 5 and 9.”[ix]

Rayner said years later, “I earned that shilling. I wouldn’t say my report was the best critique of The Hobbit that has been written, but it was good enough to ensure that it was published.”[x]

End SIDEBAR

The publishers received a lot more than one shilling as a result of trusting Rayner’s opinion. Critics loved The Hobbit. The London Times reviewer wrote, “All who love that kind of children’s book which can be read and re-read by adults should note that a new star has appeared in this constellation.”[xi]

The London Observer called it “…an exciting epic of travel, magical adventures…”. W.H. Auden called it “the best children’s story written in the last fifty years.” And when Houghton Mifflin published it in the United States in 1938, it won the New York Herald Tribune prize as the best children’s book of the year.[xii]

The first edition of The Hobbit sold out by Christmas. A reprint was hurriedly prepared, this time containing some of Tolkien’s own colored illustrations.[xiii] Since then, The Hobbit has stayed in print continuously, and has sold more than 40 million copies.[xiv]

The initial sales and acclaim for The Hobbit were such that just a few weeks after it was published Stanley Unwin invited Tolkien to London to talk about a possible sequel. Tolkien submitted a number of manuscripts he had on hand, including The Silmarillion, Farmer Giles of Ham and Roverandom, but they weren’t what Unwin had in mind. He knew that the first book about hobbits had sold really well, so he wanted another book about hobbits.

Tolkien wasn’t sure he had any more stories to tell about hobbits, but he gave it some thought. On December 19, 1937, he wrote to Charles Furth, who was on the staff at Allen & Unwin, “I have written the first chapter of a new story about Hobbits–’A long-expected party.’ A merry Christmas.”[xv]

We don’t know if Charles Furth had a merry Christmas that year or not, but many readers since then have, because ‘A long-expected party’ was the first chapter of The Lord of the Rings.

Tolkien’s “new story about Hobbits” would eventually become his masterpiece–and one of the most beloved books of the 20th century.

[i]Tom Shippey, J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century, (London, HarperCollins Publishers, 2001), p. 1.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Humphrey Carpenter, Editor, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, (London, HarperCollins Publishers, 1995), p. 215.

[iv] Humphrey Carpenter, Tolkien: A Biography, (Boston, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1977), p. 172

[v] Ibid, p. 172.

[vi] Ibid, p. 177.

[vii] Ibid, p. 179-180.

[viii] Michael Coren, J.R.R. Tolkien: The Man Who Created The Lord of the Rings, (Toronto, Stoddart, 2001), p. 73.

[ix] Carpenter, p. 180-181.

[x] Daniel Grotta-Kurska, J.R.R. Tolkien: Architect of Middle Earth, (Philadelphia, Running Press, 1976) p. 83.

[xi] Ibid., p. 84

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Carpenter, p. 182.

[xiv] Shippey, p. xxiv.

[xv] Letters, p. 27.

July 28, 2012

The Space-Time Continuum: The shape of things to come – science fiction predictions

(My Space-Time Continuum column from the May issue of Freelance, the magazine of the Saskatchewan Writers Guild.)

(My Space-Time Continuum column from the May issue of Freelance, the magazine of the Saskatchewan Writers Guild.)

Science fiction is popularly perceived as being concerned with predicting the future. It’s not hard to see where that notion comes from: after all, over the years science fiction has gotten quite a few things right about the shape of things to come.

In fact, The Shape of Things to Come was the actual title of a book by H. G. Wells (made into a landmark 1936 film). Though Wells foresaw submarine-launched guided missiles and got a few other technological predictions right, he was primarily concerned with the problems of society. The Shape of Things to Come envisioned major wars being fought in the 20th century, a distressingly accurate prediction.

Going back a bit further, Jules Verne envisioned a mission to the Moon launched from Florida in From the Earth to the Moon, and, of course, high-tech submarines in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

Last column I mentioned the various predictions Hugo Gernsback made, including microfiche, skywriting, solar power, holograms, fax machines, aluminum foil and radar.

Successful predictions during the Second World War famously got a few writers and publishers investigated by the FBI: they’d written about a terrifying new weapon that unleashed the energy of the atom itself. They knew nothing about the Manhattan Project: like the scientists themselves, they were just drawing on existing scientific knowledge.

Every day we use a technology conceived by SF writer Arthur C. Clarke: he came up with the idea of communication satellites in the 1940s, more than a decade before any satellite had been launched.

For hazardous work, scientists and engineers often use remote manipulators called “waldoes.” Why such an odd name? Because of “Waldo,” a story by Robert Heinlein, about an enormous man, trapped in orbit, who manipulated things through remote machines.

In several of his books, as early as 1942, Heinlein also described the water bed, although he foresaw it being used primarily in hospitals. More recently, Canada’s own William Gibson gave us the term and concept of “cyberspace” in his 1982 short story “Burning Chrome.”

Space exploration, of course, has always been a big SF topic. It’s been said that many, maybe even most, of the engineers and scientists who worked on the Apollo program were inspired as youngsters by Heinlein’s stories about the colonization of the moon and the planets. But that also leads to the flip side of SF predictions: the misses.

Heinlein’s futuristic space travelers tended to calculate orbits using slide rules. And when he did envision computers, he saw them as massive, building-filling monsters—he failed to foresee that computer power would increase as the machines shrank, rather than as they got bigger.

Jules Verne’s Florida-launched trip to the moon was conducted by the dubious method of loading the explorers into a giant artillery shell and firing them from an enormous cannon.

Arthur C. Clarke, in 2001: A Space Odyssey, foresaw giant orbiting space stations and a lunar colony, served by commercial flights, by the turn of the century. We didn’t make it.

Today, SF is still making predictions. Robert J. Sawyer has dealt with possibilities like the World Wide Web “waking up” and becoming sentient; immortality through the implantation of a copy of a person’s memories and personality into an artificial body; life-extension; and more.

Some of these predictions may come true. Many won’t. Considering how bleak predictions can sometimes be (global thermonuclear war between the U.S. and the Soviet Union was pretty much assumed in any number of stories I read as a kid), that’s just as well.

But the point isn’t whether the predictions come true, the point is that science fiction allows us to imagine different possibilities.

Science fiction is based on the thoroughly modern notion that the future will not be the same as the present. For most of human history, that hasn’t been the case: someone from 1211 would have felt perfectly at home two hundred years earlier or a hundred years later.

Now? Heinlein himself went from riding around in the buggy of his grandfather, a small-town rural doctor, in early-20th century Missouri to providing commentary on television on the first lunar landing. Jack Williamson, who died in 2006, travelled out west in a covered wagon in 1915 at the age of seven and wrote science fiction for some seven decades: his first story appeared in Gernsback’s Amazing Stories in 1928. Think of the changes everybody of his generation saw in their lifetimes.

I like to call science fiction an inoculation against future shock. SF writers may not get the details right, but one thing they do get right, over and over again: the shape of things to come may be wonderful, terrifying, or quite possibly both: but it won’t the be the shape of things as they are today.

Olympic throwing sports

Just in time for the Olympics (and just in time for this science column), COSMOS Magazine has run an interesting online piece by Richard A. Lovett on the history and physics of the Olympic throwing sports.

Just in time for the Olympics (and just in time for this science column), COSMOS Magazine has run an interesting online piece by Richard A. Lovett on the history and physics of the Olympic throwing sports.

It is customary, in the column-writing biz, to be up-front about any direct personal connection you have to your topic. So, full disclosure: I was a high-school shot-putter. Sad to say, Olympic caliber, I was not.

As I heaved my eight-pound lead ball an embarrassingly short distance in my one-and-only competition, however, I did wonder who on Earth ever came up with the idea of this is a sport.

The same people who brought us haggis, as it turns out: the Scots. At least that’s Lovett’s view: he thinks shot putting has as its ancestor the heaving of large stones in Scottish Highland games, and that the cannonball (the “shot” in shot put) was adopted as a more refined heaving object

The aerodynamics of the shot put are not, alas, all that interesting. Essentially, the shot putter is simply replacing gunpowder with human muscle, launching the shot into a ballistic trajectory…which means the ideal angle for distance is 45 degrees. Shot putters spin around before launching the shot simply to pick up some speed and impart more energy to the throw.

Discus throws, though, are more complicated. The discus is the only other current throwing sport besides shot put that was part of the first Modern Olympics, in 1896: but unlike the shot put, it goes all the way back to the ancient games in Athens (as statues of discus throwers from that era attest).

Lovett’s go-to source for his COSMOS article is Geoffrey Spedding, an aerospace and mechanical engineering professor at the University of Southern California. Spedding describes the discus as a “spin-stabilized oblate spheroid.” That means that the discus is designed so that if it is tilted backward slightly when it is thrown, its passage through the air creates greater air pressure on the bottom/front than on the top/back, generating lift and extending its flight. (The current records stand at over 70 metres for both men and women.) It’s “spin-stabilized” in that its spin gives it angular momentum that: like a bicycle wheel, it resists tipping, which keeps it from dropping edgewise out of the air.

Since the discus flies farther the more lift it generates, atmospheric conditions can affect its flight, Lovett notes. A 1981 paper in the American Journal of Physics found that the discus can travel more than 10 per cent farther in a 10-metres-per-second headwind than in calm air. Cold temperatures, humidity or low elevation, all of which increase atmospheric density, also help discuses fly farther.

Another throwing sport well-known to the Greeks but not a part of the first modern Olympics was the javelin, a.k.a. the spear. Javelins, Lovett notes, fly farther than any other thrown object in the Olympics. The key is the “angle of attack,” the difference between the direction of flight and the upward tilt of the point as the javelin leaves the thrower’s hand. This upward tilt, Spedding says, causes air to flow across the javelin’s curved underside, which increases pressure there while reducing it on the upper side. Just as with the discus, this creates lift and so the javelin rises.

The optimum launch angle is apparently 30 degrees (same as the discus), but the optimum angle for the javelin itself is 37 degrees. Tilt the javelin too far upward at launch and it will stall and fall short, don’t tilt it far enough and it won’t get enough lift.

And finally, there’s the weirdest throwing sport of all, the hammer throw. First of all, it’s clearly not a hammer. It gets its name from another Scottish event: throwing a sledgehammer. (The English liked it, too: King Henry VIII, Lovett notes, was reported quite good at throwing hammers. Also tantrums, but that’s a different story.) But it actually goes back much, much further, to ancient Ireland, 3,500 to 3,800 years ago, where athletes threw weights attached to ropes at the Taileann Games.

Aerodynamically? It’s still a cannon ball: a straightforward ballistic trajectory, meaning a 45-degree launch is optimal. The chain simply allows athletes to spin it much more vigorously than the shot put, imparting a lot more energy that carries it nearly four times as far.

The throwing events are only a few of those at the Olympics, of course, and every event has its own fascinating history…and fascinating physics.

Somehow, I think I already know next week’s column topic.

Auroral sounds

There are few more awe-inspiring sights in the sky than the northern lights. Probably everyone who lives in Saskatchewan has seen them multiple times, and those who live further north are even better acquainted with them…but that doesn’t mean we know everything about them.

There are few more awe-inspiring sights in the sky than the northern lights. Probably everyone who lives in Saskatchewan has seen them multiple times, and those who live further north are even better acquainted with them…but that doesn’t mean we know everything about them.

One mystery associated with the northern lights is the claim by some people that they can hear them as well as see them. Many scientists have dismissed the notion as nothing more than an auditory illusion…but now research has not only verified the existence of sound associated with the northern lights, it has recorded it and pinpointed its source in the sky.

What generates it, though, is still a mystery.

But first, a bit of background which might explain why the very notion of auroral sounds seems preposterous to some.

The proper name for the northern lights is aurora borealis. Aurora was the Roman goddess of the dawn, while borealis basically means “north”: down around the South Pole people see aurora australis instead.

From the ground, the most common auroras look like huge, shimmering, ever-shifting curtains of light, extending from east to west. Usually they’re green, although occasionally there’s also some red to them.

They’re even bigger than they look. The bottom of the curtain is about 100 kilometres up, and the upper edge can extend to 300 kilometres or higher–to the very edge of space.

Which is why, as physicist and aurora expert Dirk Lummerzheim, a research professor emeritus at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, puts it, “It is easy to say that the aurora makes no audible sound. The upper atmosphere is too thin to carry sound waves, and the aurora is so far away that it would take a sound wave five minutes to travel from an overhead aurora to the ground.”

From space, auroras don’t look like curtains at all; instead, they’re oval belts of light surrounding the geomagnetic pole. The aurora belt has an average radius of about 20 degrees of latitude (2,200 kilometres), though on rare occasions it spreads out as far as 60 degrees. It extends thousands of kilometers east to west, but it’s usually only about one kilometre thick from north to south.

Auroras are caused by the interaction between the solar wind and the Earth’s magnetic field. The solar wind is the highly energetic particles which the sun sheds constantly, at a rate of about one million tonnes per second. These particles streaming through the Earth’s magnetic field generate electrical charges–energetic electrons that are channeled poleward by the magnetic field. There they collide with particles in the upper atmosphere, exciting them: that is, imparting energy to them which they then shed in the form of light. Solar flares aimed in our direction throw a lot more particles our way, which results in more northern lights during gusty solar weather.

Sounds from intense auroras have been reported for centuries. In his book Germania the Roman historian Cornelius Tacitus (56-120AD), said people from the northern part of Germany claimed to be able to hear a faint swishing, hissing, sighing or rustling from the auroras, and that kind of anecdotal evidence has been around ever since.

Finnish researcher Professor Unto K. Laine of Aalto University’s School of Electrical Engineering, has long had an interest in aurora sounds. In a paper just published in the proceedings of the 19th International Congress on Sound and Vibration, held last week in Vilnius, Lithuania, he reports that he used three separate microphones to successfully record auroral sounds and pinpoint their location: in this instance, only about 70 meters above the ground.

Of course, that still doesn’t answer the question of why there should be any sound at all. It seems clear, however, that whatever the mechanism (or mechanisms; the researchers suspect there may be more than one since the sounds are so varied) behind the sounds are, people aren’t really hearing the distant auroras: rather, they’re hearing something produced much closer to the ground by the same energetic particles from the sun that create the auroras, particles which have penetrated much deeper into the atmosphere.

So next time you’re out in a quiet field, far from any other noise, and the northern lights fill the sky, listen close. You just might hear one of nature’s most mysterious noises.

And if anyone doubts your claim, just point them to this column.

July 21, 2012

Saturday Special: The First Two Chapters of The Haunted Horn

For this week’s Saturday Special, the first chapter of the YA/middle-grade ghost story The Haunted Horn, which I’ve just released to Kindle (other ebook formats and eventually print to follow). It’s set in Arkansas, where I went to university, although Searcy bears only a passing resemblance to the Oak Bluff of the story (although both towns share a Race Street). It’s a modern-day tale with a Civil War connection. And it’s only $2.99 for Kindle.

Enjoy!

***

The Haunted Horn

By Edward Willett

Chapter One: The Old Bugle

Alex Mitchell first saw the old bugle late one Friday—a Friday so miserable he later thought he should have taken it as an omen.

He’d started the day by being late to class; not just any class, but “Iron Head” McCullough’s science class. It was his mother’s fault—she’d lost her car keys again—but try explaining that to Iron Head. Being lectured at the front of the room in front of everybody else wasn’t made any easier to take by the fact he had the best grades in the class, and everyone knew it. By one of Edmund Kirby-Smith Junior High School’s myriad unwritten laws, that meant his classmates hated him whenever they were in the science lab.

Maybe jealous science students were responsible for the further decline of his fortunes in second-period physical education. As usual, he’d been the last one chosen for basketball (something he was used to, being, in his father’s words, only slightly taller than a fire hydrant) and then someone had hidden his clothes while he was in the shower. By the time he’d found them, rolled in a ball and stuffed in the wastepaper basket in the toilet, the Grade 7 boys who had P.E. next were already coming into the locker room, and had been greatly entertained by the spectacle of him trying to get dressed before the bell rang.

Of course, he hadn’t made it, which meant he had to sneak into Miss Hildebrandt’s English class in the middle of “To be or not to be…” Even though he was only the second-best student in her class, the other kids got a big kick out of seeing him raked over the coals a second time.

At lunch he spilled milk all over his French fries, in the library he caused an avalanche of old National Geographics, and in math he discovered he’d left his homework at home.

But the day reached what Alex would forever after consider his personal definition of “the absolute pits” when, going into geography class, he tripped over his own feet, flung out one hand to catch himself, and sent an elaborate toothpick model of the Great Wall of China crashing to the floor.

The room, which a moment before had been earsplittingly full of talk and laughter, fell silent in something approaching awe at the magnitude of that screw-up. The first voice to break the silence was Michael Sifton’s. “You’re dead, Mitchell,” he said from the doorway. He sounded pleased.

“It was an accident!”

“Don’t tell me. Tell the guy who made it. If you think it will do any good.”

The guy who made it? Alex knelt down and scooped up pieces of what used to Great Wall and now was only good for kindling. Glued to one of the largest surviving bits was a neatly typed card: “Sammy Findlater, Grade 8 Geography.”

Alex gulped. Sammy Findlater was every teacher’s idea of an All-American teenager. He was good-looking, always called grown-ups “sir” and “ma’am,” got terrific grades, and volunteered for every helpful task, from cleaning erasers to stapling test papers.

He was also the most feared kid on the playground, at the pool, downtown, or wherever else you had the supreme misfortune to run into him.

The teacher came in, took in the scene at a glance, and sighed. “Alex, I swear, you must have taught the proverbial bull in the china shop everything he knows.”

“I’m sorry, Mrs. Jordan, it was—”

“I know, I know, it was an accident. It always is. Well, pick up the pieces and take your seat.” She patted Alex on the shoulder as she passed. “Don’t worry about it, Alex; I’m sure Sammy will understand.”

“Oh, yeah, Sammy’s very understanding,” said Michael Sifton innocently. Alex sighed and finished collecting the no-longer-great Great Wall.

He was not surprised, as he made his way to the football field for marching band practice, to see Sifton talking to a tall, lean boy with short brown hair—Sammy. They both turned to look at Alex as he passed. He told himself it wasn’t really possible for Sammy’s eyes to be drilling holes in his head.

Nonetheless, he was relieved Sammy wasn’t waiting for him when band practice ended; even more relieved to see his mother was. All he wanted to do was climb into the familiar black Lincoln SUV, go home, and either watch TV or die—

—so of course his mother decided to take him with her to an antique auction.

Fortunately, he had ways to make such annoyances bearable. As a future best-selling novelist (he also had his sights set on the Nobel Prize in chemistry, but he figured that would take longer), he knew everything that happened to him should be grist for a story. Considering the way the day had gone, a horror story. He tried a few lines in his head.

Fallen leaves swirled crazily in the wake of the speeding car as it hurtled down the mountainside. The boy in the front seat peered morosely through the darkly tinted glass at the shadowed valley into which the car was descending, wondering where he was being taken, and why.

The thin, pale woman who had marched him from the schoolyard and shoved him into the black station wagon had said nothing. He’d had no word of explanation, but the principal had insisted that he go with her.

A shiver crept up his spine at the thought of her ice-cold touch, her burning red eyes and those too-perfect red lips. She hadn’t smiled, but he could have sworn he’d caught a glimpse of two protruding, sharp white teeth…

The woman was very quiet as she drove. He couldn’t even hear her breathing. It was almost like—like—

He turned his head and saw the steering wheel turning, the brake and accelerator going up and down, but no one in the driver’s seat…

“Honestly, Alex, I wish you’d quit sulking.”

Alex blinked and the story evaporated. Something Miss Hildebrandt had mentioned about a guy from Porlock flashed through his mind. “I wasn’t sulking.”

“Sure you weren’t—sitting there staring right through me. Alex, I’m sorry you’re going to miss Science World, but it comes on every day. This auction is only going to happen once.”

“Couldn’t Dad have come to get me?”

“Your father is busy at city hall.” His mother swung the car around a sharp corner, and Alex banged his elbow on the door handle.

He rubbed the sore place. “I hardly ever see him anymore,” he complained.

“He’s a very busy man. You know, if you let yourself, you might even enjoy this.”

“Oh, right. Dusty old furniture and faded pictures of guys with beards and funny mustaches. I can hardly wait.”

“Alex, for heaven’s sake, at least give it a chance!”

Alex slouched in his seat, arms folded.

They swept past the sign that said, “We hope you enjoyed your stay in Oak Bluff” and for several minutes followed what the locals called “the old highway” to distinguish it from the interstate that bypassed the town on the north. The road wound past stands of trees (just beginning to get serious about their autumn colors), stubble-covered fields and cozy white farmhouses. Alex watched the scenery pass and tried to resume his story, but couldn’t keep his mind on it. The trouble was, Oak Bluff, Arkansas, and its broad valley in the Ozarks foothills just weren’t dreary or menacing enough to serve as the setting of a horror story. At least, not in late October, with the leaves changing colors and the air cool and smoky. It was more like a setting for a rerun of Lassie.

Alex’s French horn case slammed against the back of his seat and only his seatbelt kept his forehead from likewise slamming against the dashboard. “They should’ve had a bigger sign,” his mother said.

He looked out his window at a small square of yellow cardboard mounted on a fence post. A red arrow pointed left. “Auction today. Three miles,” he read out loud.

His mother backed the SUV, then turned it onto a narrow road that wound up toward the valley rim. “Almost missed it!”

“Gee, that would have been terrible,” Alex muttered under his breath. At least this road looked more menacing. Unpaved, rutted, covered with leaves and overhung by the gnarled, arm-like branches of ancient oaks, it was the sort of road movie-teenagers were always venturing down prior to being sliced, diced and shredded by some chainsaw-wielding maniac in a hockey mask. Now that would be the perfect end to this day, Alex thought. He resumed his story. The driverless black station wagon (who was he kidding? He knew it was a hearse) turned off the paved road onto a rutted, weed-infested track that climbed toward a craggy mountain peak, crowned with lightning and thunder. Through ragged, storm-torn clouds, the boy could see—”Oof!”

“Sorry,” said Alex’s mother. “This road’s not very good.”

Alex sighed. Who could write while his insides were being turned into a milkshake? The coroner looked white—even a little bit green—as he turned away from the autopsy table. “I’ve never seen anything like it!” he said. “His insides are nothing but mush—”

Not bad, Alex thought. He glanced back at his French horn case, which had started out upright and was now upside down and wedged between the back and front seats. He knew just how it felt.

The road crossed a narrow wooden bridge marked with a faded “Watch for Flash Floods” sign, turned sharply right for a few hundred feet, and then turned right again, plunging into a hollow between two hills. The late afternoon sun stretched the car’s shadow out in front of it like a bony finger pointing the way to a dilapidated house that might once have been white, an even more dilapidated barn barely a ghost of its original red, and so many cars Alex at first thought they were approaching a junkyard—except these cars weren’t junk. “You can get that many people out to an antique auction in the middle of nowhere?” he said in astonishment.

“This is a very special auction,” his mother replied as they jolted and jounced the last eighth of a mile. “Miss Elizabeth Wainscott lived here all her life—kind of a recluse. The place isn’t much, but she packed house and barn to the rafters with one of the best antique collections in Arkansas. When she died last month, her will specified that everything be sold at auction and the money given to her only surviving relative, a nephew up in Springfield. I expect—,” they swerved in behind a silver Mercedes and jerked to a stop, “—that he’ll do all right.” She turned off the engine and picked up her purse from the floor at Alex’s feet. Alex didn’t budge. His mother sighed. “You can stay here if you like, but it’s going to be a while. You might as well get out and look around.”

“Who cares about a lot of old junk?”

“Suit yourself.” His mother tossed him the car keys. “I guess you can listen to the radio.” She got out and hurried toward the house, a snatch of auctioneer’s patter rattling around inside the car as her door opened and closed.

“If you’d buy me a smartphone I wouldn’t have to,” Alex said, but not until after she couldn’t hear him. He turned the key to ACC, but all he got on the radio was static. “Stupid hills,” he muttered. He twisted the knobs a few seconds longer, then gave in to the inevitable, switched off the radio, pulled out the key and got out of the car, shivering a little at the unexpected chill in the air in the shaded hollow. Even poking around in some old lady’s knickknacks was better than slowly going crazy from boredom in his parents’ Lincoln. “The hearse stopped abruptly, and the engine died,” he muttered under his breath as he walked past the Mercedes, two BMWs and a Corvette, toward the rhythmic chant of the auctioneer. “The boy took his chance and fled, following a weed-choked path past the rusting hulks of—of—aw, to heck with it.” He kicked a Coke can out of his path and finally stopped on the edge of the well-dressed crowd surrounding the auctioneer, who stood in the bed of a pickup truck. He wore a blue western-cut suit, a red plaid shirt, a string tie and a white cowboy hat, and brandished a cane as he accepted bids on a piece of furniture that looked like a cross between a refrigerator and a chest of drawers. “Sold! A mahogany wardrobe, to the lady in red, for $2,000.” Alex gave the piece of furniture a second, more interested glance: he’d wondered exactly what a wardrobe was ever since he’d read C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia. Two thousand dollars seemed to him like a lot of money to pay for a portable closet, but adults were always spending their money on dumb things…speaking of which, where was his mother?

Ah. He spotted her on the other side of the truck, looking at a table covered with odds and ends, and guessed she wasn’t ready to spend $2,000 on a mahogany wardrobe either. He edged around the crowd as something new went on the block: a collection of framed photographs, showing Wainscott menfolk in Civil War uniforms, both Union and Confederate. The auctioneer held up a photo of a boy with a bugle as a sample, and the bidding started at $100 for the lot.

“See anything you like, Mom?” Alex asked as he came up to her.

She smiled at him. “Got bored, huh?” He didn’t answer. “I’m afraid not. I was hoping for some nice old china, but Miss Wainscott seems to have been terribly hard on dishes.” She looked toward the house. “Unless there’s something on that table over there…”

She strode off but Alex stayed put, poking half-heartedly through the junk on the table. It consisted of items too small or insignificant to be auctioned individually, which instead had been dumped randomly into boxes and priced for outright sale. Alex dug through the first box, finding rusted horseshoe nails, ugly costume jewelry, a handful of stereoscopic views of Little Rock in 1905, a German Bible, three marbles, a bedraggled stuffed hummingbird posed rather stiffly on a piece of wire above a carved wooden flower, and a remarkably bad smell. The box was priced at $15. Alex snorted and wiped the dust off his hands onto his jeans. He was about to turn away when a sudden gust of cold wind blew back the flap on another box on the table, revealing the bugle.

At first sight it was ugly. At second sight it was even uglier. In fact, it was the most scratched, scarred, dented and dingy musical instrument Alex had ever seen. Parts of the tubing were so flattened he wondered if it could even be played. The chain or cord which had once kept the mouthpiece from falling off had been replaced with baling wire, and the entire horn was caked with what looked like a hundred years’ worth of dust and grease.

But ugly and filthy as it was, it drew Alex. He picked it up, and almost dropped it; it was heavier than it looked, and it felt—strange. His palms tingled and he quickly put the bugle back in the box. Grease, he told himself uneasily, wiping his hands again. The thing would need a lot of cleaning before he could blow it…

He shook his head. Was he nuts? The bugle’s box was marked at $20. Sure, he had $20, but he was saving for a telescope. He wasn’t about to spend that big a chunk of his saved-up allowance on—he glanced at what else was in the box—old clothes and a beat-up bugle. That would be crazy.

But then he looked at the bugle again, and wondered where it had come from. How old was it? Second World War? Maybe even the First? Or maybe it wasn’t that old at all, but had been damaged in a firefight in Vietnam and sent back with some dead soldier’s personal effects…did they even use bugles in Vietnam? Alex didn’t know. He ran his finger over the battered length of the instrument, and again felt that odd tingling. “What a piece of junk,” he said out loud. “Who’d pay twenty bucks for something like that?” He flipped the lid of the box shut.

But somehow, fifteen minutes later, when his mother returned to the car, he sat in the passenger seat turning the bugle over and over in his hands. His mother hardly glanced at him as she climbed in. “You were right, Alex. We should have gone home and watched Science World. Though if I’d had a couple of thousand dollars to spend on some of that beautiful old furniture—” She looked at him and stopped. “What’s that?”

Alex was used to explaining the obvious to grown-ups. “It’s a bugle.”

“I know that, but where—” She grinned suddenly. “‘Who cares about a lot of old junk?’, huh?”

“This isn’t junk. It’s a musical instrument.”

“Used to be, you mean.” His mother started the car. “Looks to me like it’s not much of anything, anymore.”

“It will be, once I shine it up. You wait and see. I’ll take it to school and blow it during football and basketball games. It’ll be great!”

“Well, I’m glad one of us got something worthwhile out of this little jaunt. As long as you don’t take to blowing ‘Reveille’ at six a.m….”

Alex laughed.

He held the bugle all the way home, stroking it almost like a cat. The tingling didn’t bother him anymore; in fact, he hardly noticed it. A new story started in his head. The antique dealer squinted at the ancient instrument through his monocle. “I don’t believe it,” he said in awe. “A Stradivarius bugle. Everyone thought he only made violins…”

Maybe it hadn’t been such a bad day after all.

***

Chapter Two: Sammy’s Offer

At home, on the old wooden desk beside his bed, the bugle seemed somehow larger and dirtier. Alex stared at it and wondered what had attracted him to it. It really was horned-toad ugly.

It won’t be once it’s cleaned up, he promised himself. He picked it up, and again was startled by its weight. He put it to his mouth to try to blow it, but when his lips touched the mouthpiece a spark cracked, and he jerked the horn down again. “Ow!”

As if on cue, someone knocked on the door. “Son?”

Guiltily—though he hadn’t been doing anything wrong—Alex tossed the bugle aside. “Come in, Dad.”

His father pushed the door open and stood in the doorway, nearly filling it. His dark blue business suit, carefully tailored though it was, always looked to Alex as though it were about to rip at the seams across his broad shoulders. “Alex, you left your French horn and that box you bought in the car. Go get them, then wash up for supper.”

“I didn’t buy any—oh!” Alex had forgotten about the box the bugle came in. More surprisingly, he’d forgotten about the French horn. The school would have his neck—and probably his allowance for the rest of his life—if he let anything happen to that horn. “There’s nothing in that box but old clothes. You could just throw it out.”

“No, you could just throw it out. Although since you paid for it, I’d think you’d at least want to see what’s inside it. Maybe there’s something under the clothes. If I were you, I’d hope so—that beat-up bugle sure isn’t worth $20.” His father, towering over him, followed him down the stairs. “I thought you were saving for a telescope. Why are you wasting your money on a piece of junk?” Alex groaned inwardly and quickened his pace through the hallway into the kitchen, where his mother was setting the table. “Maybe if you had to work for it like I did when I was growing up…”

Alex banged through the back door and out into the cool evening air. His father had a standard speech about how hard times were when he was growing up on a dry-land cotton farm in the Texas panhandle. He’d used it campaigning for town council. Trouble was, three months after being elected, he was still using it.

Sometimes Alex wished his father was still just managing a grocery store. He used to tell funny stories about the people who came in to shop. These days he always sounded more like the evening news.

In the garage, Alex pulled open the back door of the car and lifted out the French horn case. The box the bugle had come in he unceremoniously upended on the greasy shelf that ran along the wall next to his father’s silver sport coupe. The old clothes spilled out, thick with dust and as ratty-looking as though on the verge of becoming dust themselves. Years of filth hid their color. Alex poked at them gingerly. On top of the heap lay a coat, ripped across the front and stained with something darker than the dirt. Alex fingered the long, jagged tear. “Blood, inspector,” said the great detective. “The coat is stained with blood. Obviously someone—or some thing—slashed the poor man’s stomach open. No doubt he died instantly…” Alex jerked his finger back. It did look an awful lot like blood…

Well, whatever it was, he didn’t want it. He bundled the clothes back into the box and shoved it into a dark corner of the shelf. He’d throw it away later, when his father wasn’t around to lecture him about wasting his money.

He half-expected his father to ask him about the box’s contents during supper, but instead his dad went on and on—and on—about who had said what to whom at city hall that day and what whom had thought of it. Alex tuned him out and concentrated on shoveling in his spaghetti. He wanted to get back to his bugle.

Dessert over, he waited for a break in his father’s monologue, asked, “May I be excused?” and dashed up the stairs the moment his mother nodded. His father didn’t seem to notice.

When he picked up the bugle it shed flakes of greasy, reddish dirt onto his orange bedspread. He hurriedly brushed them off. The smudge blended into the color well enough he didn’t think his mother would notice.

Gingerly he lifted the bugle to his lips again. There was no static spark this time, but he didn’t try to blow it—not yet. He’d shine it up like new, and then surprise everyone with “Charge” or “Reveille” or “Taps.”

He cast around his room for something to polish with, and, finding nothing, slipped down the hall to the bathroom and grabbed one of the old washrags that nobody used anymore. Then he hurried downstairs to the dining room and liberated a bottle of metal polish from one of the many glass-doored cabinets filled with his mother’s growing collection of antique doodads. Ever since his father had been elected to council, his mother had been buying more and more of the things. The house was beginning to look like an antique shop. Useless old junk, Alex thought as he closed the cabinet door. At least the bugle is good for something. The kids in the band will think it’s great. And at the football game next Friday…

Back in his room, he sat on his bed, soaked the rag in the polish, then began scrubbing the bell of the dirty old horn. It was surprisingly hard work, but as the first small circle of pale-gold metal took shape under his rag and began to grow, Alex forgot about everything else. As age-old dirt melted away, fine filigrees of silver and gold appeared, he mentally wrote. What had been a shapeless mass of corrosion became a glittering, priceless work of art…

Two hours later he set aside rag and almost-empty bottle of polish and stretched his arms, wincing as his muscles complained. The bugle, unfortunately, did not look like a glittering, priceless work of art, or even new or almost-new—it was too battered and scratched. On the other hand, it was no longer a “shapeless mass of corrosion,” either. Instead…It looked somehow proud, like a leathery-faced ancient sailor, wrinkled and burned by the sun, every adventure of his long life etched on his face. Alex grinned and promised himself he’d remember that phrase for his next English composition. Miss Hildebrandt would like it. She kept telling him not to waste his time on horror stories, anyway.