Edward Willett's Blog, page 50

November 27, 2012

My favorite author thinks I’m stupid: the perils of Internet pontification

The great thing about the Internet is the way you can find out way more information than you ever used to about your favorite authors, actors, singers, etc.

The great thing about the Internet is the way you can find out way more information than you ever used to about your favorite authors, actors, singers, etc.

Or not.

Because here’s the thing: most people don’t agree with you.

Oh, don’t feel bad, they don’t agree with me, either.

Sure, you can find people who agree with you about lots of things. If you’re really lucky, that person might even be your spouse or child…but even people who agree with you about lots of things don’t agree with you about everything.

Used to be, even when I was a kid, you just didn’t know much about what your favorite authors and performers thought. You might see an interview here or there, but quite likely you would read books and watch movies without an inkling of this writer’s or that actor’s take on, say, taxation levels or foreign policy. All you knew was you really loved their books, or you really loved their movies, and really, that was enough.

Now, though…

Now, everyone seems to feel entirely free to splatter their “thoughts” (and yes, often enough the scare quotes are appropriate) about politics, religion, and their own sense of pure enlightenment all over the World Wide Web, either through their own blog or through the endless series of interviews and profiles that clutter up the Internet.

Of course they have the right: free speech and all that, and personally I put that right above all others. But just once in a while, I’d like to see a little modesty creep in. A little sense that maybe, just maybe, the other side of whatever topic is being proclaimed about might have a few points to make, too.

Because here’s the other thing. The default tone for discussion on the Internet is snark. You don’t have to engage with the arguments against your position, you just have to trot out a few well-worn phrases like “wingnuts” and “sheeple,” “libtards” and “Rethuglican,” call someone racist or socialist or fascist or some other word ending in “-ist,” and you’re done! You’ve established your bona fides as a political thinker, and all your readers (if you’re a writer) who agree with you will clap their hands in delight.

But that default snarkiness has another effect. Remember, at least half of your potential readers don’t agree with yout. It means that, for any big, divisive topic, you are alienating half of the population: and not because they disagree with your ideas, per se, but because they disagree with the way in which you present those ideas. The only reason to use an insulting tone is to insult people, and guess what? You’ve succeeded. You’ve either insulted half your audience or you’ve insulted some of their friends and family members. And the next time they see your name on a book, they’re going to remember that insult, and remember that you hold them in contempt…and quite likely they’re going to return that favor.

Of course we’ve all enjoyed books and music and movies made by people whose opinions and, often, lifestyle choices we disagree with. But pre-Internet, you could more easily overlook all that stuff because it wasn’t in your face all the time.

These days, it’s harder. And too many writers, people you would expect to be able to present a reasoned argument that accurately reflects the opposing position but presents logical reasons why it is incorrect, go straight for bombast and insult.

It’s not even the fact they disagree and insult me and friends and family who share my opinion of a particular topic that annoys me most—it’s the fact that they’ve let me down by proving themselves to be people of no particular insight, who cling to a point of view not because they have considered both sides of the issue and then made a reasoned choice, but simply because it makes them part of the political tribe they either grew up in are associated themselves with somewhere along the line.

So, will you see political rants on this blog? It’s not impossible—I have strong opinions about things, too—but I will promise this: if I decide to take on a controversial topic, I will do my best to present the other side of the argument fairly, and then explain why I chose the opposite side, and I will do my best to do so without insulting anyone.

Well, unless I’m writing about something we can all agree to hate, like boiled okra. Then the gloves are off.

November 26, 2012

A solution to the world’s food problems?

If I told you something has been built in the Australian outback in the past couple of years that can be solidly argued is one of the most important technological advances in decades, would you have a clue what I was talking about?

If I told you something has been built in the Australian outback in the past couple of years that can be solidly argued is one of the most important technological advances in decades, would you have a clue what I was talking about?

You wouldn’t? Well, I wouldn’t have either until this past weekend when I read an article by Jonathan Margolis from The Observer newspaper in England.

A little humbling, but you can’t keep up with everything. Anyway, now that I have heard about it, I’m quite excited: because it is there, in a seaside desert outside Port Augusta, three hours from Adelaide, that a company called Sundrop Farms, has built an experimental greenhouse which, as Margolis puts it, “holds the seemingly realistic promise of solving the world’s food problems.”

That’s a rather grand claim, to be sure, but the greenhouse in Australia isn’t just some small-scale experiment. It’s already growing tons of tomatoes, pepper and cucumbers—high-quality and pesticide-free—using no fresh water and close to zero fossil fuels: its water comes from the sea and its energy from the sun.

Up next: a 20-acre greenhouse (40 times bigger than the current one) that will produce 2.8 million kg of tomatoes and 1.2 million kg of peppers a year for Australian supermarkets. Projects are also underway in the Middle East.

How does it work? Motorized parabolic mirrors in a 75-metre-long line follow the sun, focusing its heat on a sealed pipe with constantly circulating oil. The hot oil transfers its heat to tanks of seawater pumped from a few metres below ground (the sea is only 100 metres away).

The hot oil heats the seawater to 160 degrees C., and the resulting steam is used to drive turbines, generating electricity. Some of the hot water heats the greenhouses on cold desert nights, while the rest goes into a desalination plant, which produces 10,000 litres of pure, fresh water for the plants. The grower (Dave Pratt, a Canadian from Ontario, described by Margolis as “a hyper-enthusiastic 27-year-old”) can add whatever nutrients are required to the water to make the plants thrive: some of those nutrients come from the salts and minerals extracted from the seawater (the rest is sold to interested third parties).

Driving air, via wind and fans, through water trickling over a wall of honeycombed cardboard evaporative pads keeps the greenhouses humid and cool.

How high-tech is the greenhouse? Pratt can control all the growing conditions via an iPhone app, whether he’s actually at the farm or back home in Canada.

Grown under such controlled conditions, the crops are blemish-free, ideal for supermarkets, and they’re also pesticide-free: although obviously a few pests sneak into the greenhouse, they can be eliminated naturally. As a result, the produce is essentially organic (although it can’t be marketed that way in Australia because the rules prohibit using that term for crops that aren’t grown in soil). For pollination purposes, the greenhouse has its own flight of in-house bees.

As Margolis writes, Sundrop Farms appears “to have pulled off the ultimate something-from-nothing agricultural feat—using the sun to desalinate seawater for irrigation and to heat and cool greenhouses as required, and thence cheaply grow high-quality, pesticide-free vegetables year-round in commercial qualities.”

The new expanded greenhouse, while producing $12 million (Aus.) a year worth of produce, is expected to annually save the equivalent of about 4.6 million barrels of oil and 280 million litres of fresh water compared to a standard greenhouse in a similar location. The potential reduction in energy and water usage worldwide if the technology were adopted in other locations where fresh water is short but sun and seawater are abundant is clearly enormous; and since agriculture currently uses 60 to 80 percent of the planet’s fresh water, enormously beneficial.

Is there a catch? It’s hard to find one. Neil Palmer is the head of Australia’s government-funded desalination research institute. Margolis quotes him as saying, “They are making food without risk, eliminating the problems caused not just by floods, frost, hail, but by lack of water, too, which now becomes a non-issue. Plus, it stacks up economically and it’s infinitely scalable.”

We’re all on a one-way journey into the future. It’s encouraging to remember there are routes we can take to a brighter rather than dimmer future: and those routes, almost always, are blazed for us by science and technology.

On suffering the affliction of Editor Brain

It’s always a mistake to make a grand pronouncement that one is going to make a valiant attempt to post regularly to one’s blog again, especially after having made similar grand pronouncements in the past and then not following through, but…

It’s always a mistake to make a grand pronouncement that one is going to make a valiant attempt to post regularly to one’s blog again, especially after having made similar grand pronouncements in the past and then not following through, but…

Consider this my grand pronouncement.

It’s not as if I can’t come up with words. Give me a keyboard, I make words. It’s kind of like a reflex, something hard-wired, although I’m not quite sure how it evolved since it seems unlikely I’m the descendant of ancient proto-humans who survived to reproduce only because they were good at wriggling their fingers while making up stories.

In any event, here I am at the keyboard, and typing, and the thing that prompted this sudden surge of verbiage was the fact that I seem to have come down with a distressing affliction.

I call it Editor Brain.

Here’s the backstory. From last fall until last spring, I was writer-in-residence at the Regina Public Library, in which capacity I met with some 75 individual writers and helped them (to the best of my ability and their willingness to be helped) with their various projects, which ran the gamut from children’s stories to poetry to nonfiction to fantasy epics. This involved a lot of reading and a lot of notating of other author’s manuscripts.

With the conclusion of my nine-month term (and, alas, the end of regular paychecks) I decided it was time to hang out my shingle as a freelance editor, my theory being that with so many people seeking to self- (ahem) ah, independently publish their manuscripts, there will be growing need for people willing to edit those manuscripts.

I’ve had a few inquiries since then and recently completed my first full-fledged novel editing job, of an epic fantasy. I discovered a few things.

First, I discovered I was drastically undercharging. Apparently it takes me longer to edit someone else’s book than to self-edit my own. Lesson noted.

Second, I discovered that editing someone else’s work is a grand way to look critically at one’s own work. Focusing closely, on a line-by-line basis, on the weaknesses and verbal tics and oversights in someone else’s novel has made me more aware of my own failings in those regards as I look at my own work, which is useful what with a new fantasy trilogy starting in a few months’ time. (Masks, by E.C. Blake, DAW Books, November 2013. Don’t worry, I’ll remind you.)

But third, I discovered that once you get the editing part of your brain into high gear…it’s hard to shut it off. Hence Editor Brain.

While still in the throes of editing this other author’s fantasy epic, I began reading the third book in a quite successful fantasy trilogy I had very much enjoyed the first two books of. I remember thinking of the first book in particular how marvelously it was written, how evocative certain passages were, how wonderful the action scenes were, etc., etc.

But as I started reading the third book, I instead started thinking, “This bit of dialogue is clunky…that bit of description is dull…this action scene could stand some tightening up.”

I’m still enjoying the book, don’t get me wrong—but not in the same way I remember enjoying the first book of the trilogy. I’m seeing the seams in the world-building, spotting the rivets holding things together, noticing the dust bunnies under the furniture, that sort of thing.

It is precisely, I think, like what happens when I go to a play or musical. Having done a considerable amount of acting myself, both in community theatre and professionally, I notice things like how the sets are put together, where they hung the lights, how effective (or ineffective) the sound effects are. I know what happened backstage when an actor had to make a quick costume change, because I’ve been in that position…and so forth.

When I was in my 20s, having come back from Harding University where I sang in the top-notch A Cappella Chorus, I remember once listening with my father to a recording he had made of a recent concert by the high school chorus he directed. We were commenting back and forth on where the sopranos were a little flat and where the diction wasn’t what it should have been, and my mother eventually burst out, “Can’t you just listen to the music and enjoy it?”

Well, yes, we could…but it’s not as easy as it used to be.

Editor Brain has the same effect. Yes, I can read just for pleasure…but it’s not as easy as it used to be.

On the flip side, the more I work with other writers, the better, I hope, I’m able to craft my own writing. The ultimate goal? Creating work of my own that other people can read for pleasure without being brought up short by some clumsiness of expression or infelicity of dialogue.

Except, probably, for other people who, like me, are afflicted with Editor Brain.

Alas, from what I hear from other writers and editors, there is no cure. Still, with perseverance and determination, I do hope to continue to live a normal life.

October 20, 2012

Butterfly buildings

At the end of August and beginning of September, I and my wife and daughter were in Chicago for the World Science Fiction Convention…and a fair bit of touristy sightseeing, including taking in the (highly recommended) architectural river tour offered by the Chicago Architecture Institute.

At the end of August and beginning of September, I and my wife and daughter were in Chicago for the World Science Fiction Convention…and a fair bit of touristy sightseeing, including taking in the (highly recommended) architectural river tour offered by the Chicago Architecture Institute.

In the little over a decade since the last time we were there, numerous new skyscrapers have sprung up, each unique, each adding its own unique features to one of the world’s greatest city skylines. I particularly liked the Trump Tower (the one in the photo), now the second-tallest building in the city, whose pale blue glass blends beautifully with the sky and the reflection from Lake Michigan.

But if research led by Shu Yang of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia pans out, future skyscrapers may be even more spectacular. Shu Yang envisions buildings coated with artificial butterfly wing material, as brilliant iridescent as anything in nature.

I admit I would have missed the significance of Yang’s work if not for a report on it by Joanna Carver, a reporter for NewScientist’s Short Sharp Science blog (newscientist.com/blogs/shortsharpscience), since even had I come across Yang’s paper in the journal Advanced Functional Materials on my own, I probably wouldn’t have realized that “Exploiting Nanoroughness on Holographically Patterned Three-Dimensional Photonic Crystals” could lead to butterfly buildings.

Nor I admit, would the first sentence of the summary, “The fabrication of three-dimensional (3D) diamond photonic crystals with controllable nanoroughness (

But apparently, butterfly buildings is indeed where this could lead.

As Yang points out in the introduction to her paper, “structural coloration” (as opposed to coloration produced by a pigment, as in paint) is usually the result of the interference, diffraction, or scattering of light by arrays of transparent materials. For example, if you have a stack of thin, transparent films whose refractive (light-bending) properties alternate between low and high, you get a strong reflection of light…and interference of the light waves can lead to complete “stop bands” or “photonic band gaps,” allowing certain wavelengths of light to be reflected totally while others or not.

The classic example of this is in butterfly wings. The Morpho butterfly’s wings are brilliantly blue because of this kind of interference. They are also “superhydrophobic”—extremely water repellant—due to “nanoroughness,” roughness at an extremely small scale.

Yang set about to recreate this butterfly-wing combination of iridescent colour and superhydrophobia by using a technique called holographic lithography, using a laser to make a 3D cross-linked pattern in a special kind of material called photoresist. A solvent is then applied to wash away all of the photoresist untouched by the laser, and the result is a 3D structure that has the structural coloration seen in butterfly wings. A second solvent is then applied that roughens the surface, creating the nanoroughness that makes butterfly wings water-resistant.

There are multiple uses for such a coating. Yang has a grant to develop butterfly-inspired coatings for use on solar panels. In that case, the water-resistance would be the key selling feature: such coatings would keep the panels drier, cleaner, and hence more efficient.

But she is also working with architects to create a low-cost version of the material for use on buildings. “The structural colour we can produce is bright and highly decorative.” And, of course, water-resistant, so it wouldn’t have to be cleaned as often. Plus, Carver says in the Short Sharp Science article, such coatings could be connected to a computer and tuned at will to produce whatever colour/transparency combination was desirable. A prototype version of the coating is supposed to be available by June.

Who knows? By the next time I get to Chicago, there may be new buildings that gleam with iridescent color like giant, folded butterfly wings…and I’ll be able to impress the architectural river tour guide.

“Oh,” I’ll say. “I see your architects are now exploiting nanoroughness on holographically patterned three-dimensional photonic crystals. I’ll bet they’re using epoxy-functionalized cyclohexyl polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes.”

At which point, of course, I’ll probably get thrown off the boat.

But it’ll totally be worth it.

October 7, 2012

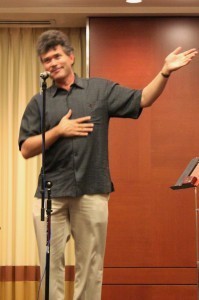

Sing, sing a song…

I’ve sung all my life, in church, in choirs, and on-stage, both just for fun and professionally. And through all those years, I’ve heard music teachers say anyone can learn to sing…and the occasional person who counterclaims (and through their singing seems to support the statement) that, well, no, they can’t.

I’ve sung all my life, in church, in choirs, and on-stage, both just for fun and professionally. And through all those years, I’ve heard music teachers say anyone can learn to sing…and the occasional person who counterclaims (and through their singing seems to support the statement) that, well, no, they can’t.

So…who’s right?

In “Singing proficiency in the general population,” a study conducted by psychologists Simone Dalla Bella of the University of Finance and Management in Warsaw, and Jean-François Giguère and Isabelle Peretz of the University of Montreal, and published in the February 2007 Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, the researchers point out that “singing abilities emerge spontaneously and precociously,” with the first songs being produced at around one year of age and recognizable songs starting to emerge at 18 months. This indicates that singing is really does come naturally to humans…yet, most people believe that the ability to carry a tune is unevenly distributed in the general population.

To test that belief, the psychologists recruited 20 individuals (a.k.a. Group 1), 10 males and 10 females aged 19 to 29, from the University of Montreal community, and an additional 42 individuals (Group 2), 19 males and 23 females, selected randomly in a public park. Group 1 was deliberately made up of non-musicians and no selection based on musical ability was made in Group 2 (whose members were told by the experimenter it was his birthday and he had made a bet with friends that he could get 100 individuals each to sing the well-known refrain to the song Gens du pays in honour of that fact).

Four professional singers were also recruited, along with Gilles Vigneault, composer and singer of Gens du pays. Group 2 singers were recorded on the spot, while Group 1 singers and the professionals were recorded in the laboratory. Vigneault was recorded in a studio.

The recordings were analyzed, both by a group of 10 non-musicians and by computer, for accuracy in pitch and time duration of the notes. The result: the occasional singers were found to have less control over pitch relative to time as compared to expert singers and tended to produce more out-of-key pitch intervals than the professionals, as you might expect. But the researchers noticed that the occasional singers also tended to sing the piece much faster than the professionals—and those who slowed down exhibited accuracy comparable to the professionals, suggesting some of those errors were simply caused by rushing.

(The rushing wasn’t surprising: the findings suggest occasional singers don’t remember tempo well: the tempos they chose only fell within eight percent of the tempo of the most frequently heard recordings 11 percent of the time. On the other hand, even untrained singers show a remarkable sense of absolute pitch: 72 percent of the performances placed the first note within two semitones of the original first note in the recordings.)

To test the hypothesis that rushing caused the bulk of the errors, the researchers did a follow-up study with 15 participants from Group 1 three years later. They found that when they slowed the singers down with a metronome, pitch accuracy increased dramatically, falling within the range exhibited by the professionals.

All of which suggests, as music teachers would have it, that singing is indeed a widespread skill, and what most people lack isn’t ability, but training.

But there really are exceptions. Two participants were unable to correct the numerous pitch errors they made, even though they could sing in time and were normal at detecting pitch errors in other music. In other words, they knew they were singing off-key, but were unable to correct it.

That distinguishes them from the four percent of the population that is literally tone-deaf, unable to distinguish differences in pitch. These singers could distinguish the correct pitches, they just couldn’t produce them.

Which means that, indeed, there are people who literally cannot sing on-pitch…but very few of them. The real take-away of the study, according to the authors, is that “singing in the general population is more accurate and widespread than is currently believe. The average person is able to carry a tune almost as proficiently as professional singers…In short, singing appears to be as natural as speaking with the added value of promoting social cohesion and activity coordination at a group level.”

And that, for sure, is something to sing about.

September 30, 2012

Saturday Special: Lisa Fernando and Canada’s epidemic response team

In view of the announcement this week that Canada will send a mobile laboratory to help stem an outbreak of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of Congo, I offer an account of a similar effort from Canada to help combat an outbreak of Marburg hemmorhagic fever (closely related to Ebola) in Angola a few years ago, condensed from a chapter in my book Disease-Hunting Scientist: Careers Hunting Deadly Diseases (Enslow Publishers).

***

“You’ve got to be kidding me!”

“You’ve got to be kidding me!”

It was 2005, and Lisa Fernando had just been told she would be flying to the African nation of Angola within a week to help battle an outbreak of Marburg hemorrhagic fever. (A hemorrhagic fever is a disease whose symptoms typically include high fever and internal bleeding.)

Fernando had only been working at the Canadian Science Centre for Human and Animal Health in Winnipeg, Manitoba, for 2 1/2 years. She’d started there shortly after she received her master’s degree in medical microbiology. (That’s the study of the tiny organisms, such as bacteria and viruses, that cause disease.)

The Canadian Science Centre for Human and Animal Health is a joint facility, home to both the Public Health Agency of Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency’s National Centre for Foreign Animal Disease. It’s also home to the country’s only “Level 4” laboratories. A Level 4 laboratory is one that can meet the strict safety standards for working with some of the world’s most dangerous disease-causing agents, such as the Marburg virus.

Marburg is closely related to the Ebola virus, the best-known of the disease organisms scientists study in Level 4 labs. But until the outbreak in Angola, confirmed by the World Health Organization in March, 2005, nobody realized that Marburg could be just as deadly as Ebola.

There is no cure for Marburg hemorrhagic fever, just as there is no cure for Ebola. At the time Fernando got the call to go to Angola, the nine out of every 10 people infected during the outbreak had died. A person can easily become infected if they are in contact with bodily fluids (such as blood) from an infected person.

Well-prepared, but still…

Even though the call to go to Angola surprised her, Fernando was no stranger to working with deadly germs. She had been training to do just that for her whole 2 1/2 years at the Winnipeg lab. “Working with these viruses every day, I really had developed a comfort level,” she says. “I felt well-prepared.”

Still, when “the big boss” (Dr. Heinz Feldmann, chief of special pathogens at the Public Health Agency of Canada) told her she was going to Angola, her surprise was tinged with just a bit of fear. It would be her first overseas mission.

She battled the fear with logic. “Of course there’s all these thoughts that go through your mind, so then you logically think, ‘We’re not visiting the people in the field, and for the samples that we’re handling, we’re following all the same safety requirements as we do in Winnipeg.” The only difference, she says, is that in the field they wouldn’t have “the fancy Level 4 lab.”

Fernando says she knew she had been well-trained and she had a tremendous amount of trust in Dr. Feldmann. “He would never bring us into an area where he was worried about our safety or well-being,” she said. “I just had to trust in his experience.”

Feldmann knew exactly what the team would be getting into, because he was already in Angola. He had gone there as part of the first team Canada sent, along with a mobile laboratory containing the equipment needed to diagnose Marburg. After three weeks in Angola, Feldmann found that cases were increasing and the demand for the lab remained high. That was when he called for Fernando and medical officer Dr. Jim Strong to relieve him and his lab assistant, Allen Grolla.

“I didn’t quite totally believe it until I was actually on the plane with Jim,” Fernando says. “There had been a lot of discussion back and forth through the week leading up to us leaving, you know, ‘Oh, are we really going? Do we have visas? Do we have flights booked? Are there more cases?’ With us being so far away it was hard to really know what the situation was.”

Do not lean on the airplane door

The outbreak began in the northern Angolan city of Uige (pronounced Weej). Getting there was not easy.

“You would fly into Luanda, which is the capital of Angola, and then you would have to take an hour flight in this tiny little four-seater plane,” Fernando recalls. “I remember the first flight out, the pilot leaned over, pulled the door shut, and said, ‘Just don’t lean on it.’ And I thought, ‘This is the last flight I will ever take.’ But at least it was adventurous!”

Conditions were primitive in Uige. The city and the surrounding countryside were badly affected by the civil war that had gripped Angola until just a couple of years before the outbreak. “It was war-torn,” Fernando says. “Everywhere you would look, the windows had been blown out, you would see gunshot holes. Dusty streets, very barren.”

She and Dr. Strong were put up in a hotel…of sorts. They had to share one room, called the honeymoon suite because, unlike the other rooms, it had an attached bathroom. However, the bathroom did not have running water.

“The shower was a bucket shower,” Fernando says. “You had a big tub of water which they would cart in every second day at least, and then you would just bucket shower that way.” They used bottled water to brush their teeth. They had an air conditioning unit, but they had no electricity to run it.

“It was very, very humble, but we got by,” Fernando says. She also notes that the food was sometimes “questionable.” Almost everyone the trip had diarrhea at some point.

Humble surroundings, important work

The words “mobile laboratory” might make you imagine a gleaming air-conditioned semi-trailer. The mobile lab Fernando and Strong worked in, however, was nothing of the sort. “No air conditioning, no running water,” Fernando says.

Everything in it was transported to Angola in six to eight rubber bins. The bins were simply put aboard commercial airplanes as checked luggage. Once the lab was delivered on site, it could be up and operating within two hours.

The mobile lab contained various test kits, a generator, a laptop computer designed to withstand humidity, dust, and heat, and a satellite phone. It also contained personal protection equipment, to insure the scientists did not infect themselves as they worked with samples from patients.

Using the lab, workers could determine who was infected and who was not. That was vital information, because the only way to bring an outbreak under control is to prevent uninfected people from coming into contact with infected people, and thus contracting the diseases.

The most important piece of equipment in the lab was a device called a “real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT PCR) unit.” The RT PCR copied the incredibly tiny bits of genetic material found inside viruses over and over again. Once there wa enough of it, it could be identified.

Fernando and the others would receive samples–typically blood samples or swab samples–for people who might be infected with Marburg. They would examine those samples, with the help of the RT PCR, for the presence of the Marburg virus.

They ran the lab in a room at the Uige Provincial Hospital, where the outbreak was first identified. At the time of the outbreak, that hospital, and its four doctors, were the only health care available for the 1.5 million people in the region. Some of the earliest victims of outbreaks of both Ebola and Marburg are often the medical staff at the hospitals where the first patients are taken. The Angola outbreak was no exception. Among those who died early on were two doctors and sixteen nurses.

Fernando says that by the time they got there, the doctors running the isolation ward (a special, sealed room where people with contagious diseases are place so they don’t infect others in the hospital), wouldn’t even attempt to treat a patient until they had a diagnosis from the lab.

That made the Canadians’ work doubly important. Fernando says that malaria is a huge problem in the region, and many of the children being brought to the hospital with symptoms similar to Marburg actually had malaria. Malaria can be treated, but the doctors wouldn’t even attempt to help the children until they were certain they didn’t have Marburg.

Taking precautions

Fernando and Strong were not working directly with patients, but they still had to take precautions because they were dealing with samples that might contain Marburg virus. The lab tests themselves were run on killed virus–but that meant the first step was killing live virus.

While they were working with potentially live virus, Fernando and Strong wore something similar to the Level 4 “space suit” (described in more detail in the next chapter). The suit had its own battery-operated breathing supply, drawing in air through a HEPA (High Efficiency Particulate Air) filter, a filter so fine even viruses can’t get through it. The suit also had rubber boots, taped at the top, and three pairs of gloves. “It’s like wearing this big snowsuit and it gets very, very hot in there,” Fernando says. “At times we were in that suit for an hour or two.”

(The current edition of the mobile lab, sent to the Democratic Republic of Congo for a 2007 Ebola outbreak, includes a high-tech box called an “isolator.” A scientist can reach inside the isolator and work on viruses without having to wear an uncomfortable full-body suit.)

After three weeks in the field, Fernando returned home for a month. Then she went back to Angola for another three weeks, because the World Health Organization wanted the lab to remain in Angola for three weeks after the last lab-confirmed case.

“We came home, ironically, the day before Canada Day (July 1), and that was the best Canada Day ever. I remember thinking, ‘Flushing toilets! Right on!’ I had never been so grateful for running water and electricity!”

Ready to go again

So far, Fernando has not been called for another outbreak. But she is ready to go if asked. “If there is the need, absolutely. I think that it is a great humanitarian effort and I think that as a scientist, it’s sometimes very easy to forget that this virus actually kills people.

“When you work in a lab you’re working with very artificial systems, with cell lines, cells that we use to grow up the virus. It’s easy to forget that this is an actual disease that kills people and affects families.”

She says that going to Angola really helped her put her research into perspective, because the main project she is working on is focused on developing a vaccine for both Marburg and Ebola. Seeing the effects of the disease in Angola has reinforced for her the importance of her job in Winnipeg.

When she was growing up, though, working with deadly viruses was certainly not what she thought she would end up doing as a career. “I mean, I had no idea what a Level 4 virus was,” she says. Instead, the job just “fell into her lap,” when Heinz Feldmann offered her a job as a biologist with the group shortly after she completed working on her master’s degree with him.

High-school interest pays off

But if working with Level 4 viruses was not something she always thought she wanted to do, working in a research lab certainly was. Fernando says became interested in biology and chemistry in high school and knew early on that she would study science in college.

“My second year I took a micro(biology) course, and I fell in love with bacteria. Then when I finished my degree I knew that I wanted to do research, so doing a master’s was the first step in that direction.”

She says that was the best decision she ever made, because it helped her understand exactly what research involved. It also proved to her that she did not want to go on to obtain her Ph.D. With that more advanced degree, she says, “You kind of get stuck working behind a desk or writing grants or writing papers. I wanted to be more involved in the lab.”

Even though she enjoys it, “Research is hard,” Fernando says. “We often say in the lab it’s 90 percent failure, 10 percent success.”

Fernando says she laughs whenever she watches the 1995 movie Outbreak, the best-known fictional version of the kind of work she does. “I love the way they find a cure in 24 hours, and the scientists fall in love. Really, we don’t lead glamorous lives like that. Research is hard: it’s mostly failure. You get maybe one day of success out of the whole year. You have to be the type of person who can put up with that frustration and be very patient.

A hero? No way!

Fernando says the question she was most often asked by media in Canada at the time of the outbreak was, “Do you consider yourself a hero?”

She found it hard to believe they would even ask her the question. “Everyone I know in this business, the colleagues of mine that went to Angola, none of us are this for the glory or the money, because there isn’t a lot of money in science,” Fernando says. “We’re not in this for the front-page news, not at all.

“We’re just here to do our job.”

September 22, 2012

The Space-Time Continuum: Cynicism vs. hope in science fiction

The Hunger Games may be getting all the attention right now, but there’s a long history to dystopian science fiction. War of the Worlds, Brave New World, 1984, A Canticle for Leibowitz, A Handmaid’s Tale…the list goes on and on. I’ve written some myself.

The Hunger Games may be getting all the attention right now, but there’s a long history to dystopian science fiction. War of the Worlds, Brave New World, 1984, A Canticle for Leibowitz, A Handmaid’s Tale…the list goes on and on. I’ve written some myself.

Dark and dangerous futures are, of course, ripe settings for fiction. (As are dark and dangerous pasts or presents, for that matter.) They provide the author with plenty of opportunities for adventure and excitement, as the heroes struggle to survive against nature, their fellow humans, or (in science fiction and fantasy) aliens, zombies, goblins or what-have-you.

I mean, there’s a good reason you don’t see many Star Trek stories set on Earth: Earth is presented as pretty much a perfected utopia, and unless it’s threatened from outside, it just doesn’t offer many storytelling opportunities.

But David Brin, scientist, inventor, and New York Times-bestelling science-fiction author, thinks the tendency to paint the future using only the darkest colours of the palette is “what is wrong with science fiction today.”

He makes the statement in a recent interview on the website Geekwire. “Too many authors and film-makers,” says Brin, “buy into the playground notion that cynicism is somehow chic and knowing.”

“Playground notion” seems a particularly apt phrase to me and, I suspect, anyone else who has worked a lot with teen writers. There’s a phase young writers tend to go through where every story has to be dark and depressing. I think it’s an effort to achieve gravitas, to write something deep and important, although in practice that means, if you’re reading a lot of teen writing, way too many stories involving car crashes, cancer, death or abuse. Brin seems to be saying, and I’d concur, that some writers never grow out of that phase.

Brin continues: “So many 50- or 80-year-old clichés are rampant (e.g. “hey look, I invented suspicion of authority!”) while nostalgia pushes aside what used to be our genre’s golden notion: that we in this civilization might find ways to improve, to solve problems, to become better than we were.”

A difficult task, he admits, “fraught with many pitfalls.” But, he says, too many creators portray the future as hopeless.

“How pathetic!” says Brin. “That beneficiaries of relentless progress should repay that debt by casting doubt on the very possibility of progress?” Nor is this political, in his view. “I see the habit spewing from both ends of the hoary, lobotomizing so-called ‘left-right axis.’ My late, lamented friend Ray Bradbury called this fetish the very lowest form of ingratitude.”

“But wait!” some may cry. “It’s not realistic to portray the future in sunny terms. Just look at all the problems in the world today!”

Brin doesn’t deny that there’s a place for dark fiction. He points to Bradbury again. “Ray plumbed the darkest depths of the human soul, in tales that could freeze your heart. So? He considered fantasy chills and terrifying sci-fi what-ifs to be part of exploring our dark corners and failure modes.” But, he continues, those dark stories were “always aiming to achieve effective warnings. Self-preventing prophecies.”

You might call that dystopia-as-prophylaxis: by presenting a dark and disturbing future, and detailing how our present led directly to it, you can convince people in the present to take the steps necessary to prevent that future. (Would 1984 have been more like 1984 if George Orwell had never written 1984?)

“Some of us are rebelling,” says Brin. “Neal Stephenson, Kim Stanley Robinson, Greg Bear and others have been laying down a challenge to our peers. If you think we have problems, expose them! But spare a little effort to suggesting solutions. Or stoking others with belief that we can.”

Of course, then you face counter danger: that, rather than wallowing in cynicism and hopelessness, you end up writing your story from atop a soap box or behind a pulpit. That can turn readers off, and if they never finish your book, they’ll never be exposed to your solutions for the problems you foresee.

That may happen anyway if they disagree strongly with either your diagnosis or your solutions you present. Pace Brin, that really does get into politics, because for every person who thinks “the government ought to do something” there’s another who thinks the government does way too much already and is far better at making things worse than it is at making things better.

But if you write a compelling story, even those who disagree with you will read to the end. And if they end up arguing with you along the way, or arguing about your ideas with others, then you’ve still done something to shape, and hopefully, improve, the future.

The broad gate and road lead to fictional futures of cynicism and hopelessness, while the narrow gate and strait road lead to possible futures where things may yet be better than they are today.

Or, to paraphrase another famous quote, “Cynicism is easy…hope is hard.”

September 19, 2012

Throwing like a girl

There’s a scene in Huckleberry Finn where Huck is attempting to pass himself off as a girl, but is betrayed, in part, by the way he throws a lump of lead at a rat: “And when you throw at a rat or anything, hitch yourself up a tiptoe and fetch your hand up over your head as awkward as you can, and miss your rat about six or seven foot. Throw stiff-armed from the shoulder, like there was a pivot there for it to turn on, like a girl; not from the wrist and elbow, with your arm out to one side, like a boy.”

There’s a scene in Huckleberry Finn where Huck is attempting to pass himself off as a girl, but is betrayed, in part, by the way he throws a lump of lead at a rat: “And when you throw at a rat or anything, hitch yourself up a tiptoe and fetch your hand up over your head as awkward as you can, and miss your rat about six or seven foot. Throw stiff-armed from the shoulder, like there was a pivot there for it to turn on, like a girl; not from the wrist and elbow, with your arm out to one side, like a boy.”

There’s a reason “You throw like a girl!” is a classic schoolyard taunt: boys really do throw better than girls, as freelance science writer Tamar Haspel points out in an article published in the September 10 Washington Post.

As Haspel recounts, Janet Hyde, a professor of psychology and women’s studies at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, has studied the gender gap across a variety of skills, analyzing the vast quantity of data collected over the years in studies of social, psychological, communication and physical traits, skills and behaviors. She’s found only two skills in which there is a “very large” difference between boys and girls: throwing velocity and throwing distance.

Jerry Thomas, dean of the College of Education at the University of North Texas in Denton, who has researched the “throwing gap,” told Haspel, “The overhand throwing gap, beginning at four years of age, is three times the difference of any other motor task, and it just gets bigger across age. By 18, there’s hardly any overlap in the distribution: nearly every boy by age 15 throws better than the best girl.”

It’s cross-cultural: around the world, pre-pubescent girls throw only 51 to 69 percent of the distance that boys do, at only 51 to 79 percent of the velocity. The difference increases with age: one U.S. study found that girls age 14 to 18 threw only 39 percent as far as boys.

There is a “nurture” factor: in most cultures boys start throwing earlier and throw more often than girls. But a study Thomas carried out with Australian aboriginals, in whose culture both men and women hunt and both sexes throw from childhood, found that, although aboriginal girls threw significantly better than girls from other cultures, they still threw at only 78.3 percent of the velocity of boys.

The widening gap after puberty can be explained by differences in size and strength, but before puberty? It all comes down to style.

Hamal writes, “According to Thomas, a girl throwing overhand looks more like she’s throwing a dart than a ball. It’s a slow, weak, forearm motion, with a short step on the same side as the throwing hand. A boy’s throw, by contrast, involves the entire body.”

Thomas goes on to say that a skillful overhand throw uncoils in three phases: step with the foot opposite the throwing hand, rotate with the hips first, then the shoulders, and whip with the arm and hand. Girls don’t do any of these as successfully as boys, but the biggest problem is rotation. The separate turning of hips and shoulders is what gives a throw its power. Women tend to rotate their hips and shoulders together.

OK…but, why? There’s no apparent muscular or structural reason.

Thomas’s best guess is that it’s neurological: girls’ brains default to a different throwing style than boys’. It makes some kind of evolutionary sense: among our ancestors, men typically threw rocks, and those that threw them well got more food, and more women. Women did the gathering and often had a baby with them. Women may not rotate their hips and shoulders separately because they’ve evolved to throw while holding a baby, Thomas suggests.

Saying the difference in throwing styles is hard-wired isn’t the same as saying girls should just give up on throwing, though. Jenn Allard, who has coached women’s softball at Harvard for 18 years, says overhand throwing is the most under-taught skill in softball. If you don’t want to throw like a girl, you don’t have to.

Or vice versa. Should any modern-day Huck Finn have a need to pass himself off as a girl, he can learn the skill of throwing like one…just as long as he doesn’t need to kill any rats.

September 12, 2012

Chicon 7: the 70th World Science Fiction Convention

(Note: if you’re thinking this doesn’t exactly read like a typical convention report from a SF writer, that would be because this is actually my weekly science column. A slightly different version will be my column for the next issue of the Saskatchewan Writers Guild newsletter Freelance. Never let a convention go to waste!

(Note: if you’re thinking this doesn’t exactly read like a typical convention report from a SF writer, that would be because this is actually my weekly science column. A slightly different version will be my column for the next issue of the Saskatchewan Writers Guild newsletter Freelance. Never let a convention go to waste!

(The photo is of Betsy Wollheim and Sheila Gilbert, co-publishers and co-editors of DAW Books, among whose authors I am proud to count myself. Betsy is holding the Hugo Award for Best Professional Editor (Long Form), a long-overdue tribute to one of the best editors in the field.)

Most people plan their summer vacations based on places they’d really like to go or people they’d really like to see.

Us? We plan it around the World Science Fiction Convention, which meant that this year, we vacationed in Chicago.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking, “Science fiction convention? Isn’t that one of those wacky events where everyone dresses up in Star Trek uniforms and swings light sabers at each other?”

To which I can only reply, “Well, yes, sort of…but that’s only a small part of it.”

This year’s World Science Fiction Convention, the 70th of its ilk, and the seventh to be held in Chicago (hence the convention’s title, Chicon 7) drew more than 5,000 people to the Hyatt Regency in the heart of downtown over the Labor Day weekend (from Thursday to Monday), and it’s safe to say no two of those people experienced the convention in exactly the same way, because at a WorldCon there are so many things happening all at once that a dozen people could arrive together and never see each other again for the entire weekend.

As the website (www.chicon7.org) points out, WorldCon this year offered discussions on writing, publishing and criticism; comics and graphic novels; film, television and other media; art; anime and cartoons, and costuming.

But that’s not all: there was also a very strong science track.

Guests of Honor were author Mike Resnick, artist Rowena Morrill, agent Jane Frank, fan Peggy Rae Sapienza, author John Scalzi, who acted as toastmaster…and astronaut Story Musgrave. A very special science guest was Sy Liebergot, the NASA Apollo EECOM Flight Controller in Mission Control for all Apollo manned missions and all Skylab program missions.

Admittedly, I was focused more on science fiction and fantasy than on science while I was there: my wife actually took in more science programming than I did. I did things like sign autographs (a few—my line, alas, did not stretch out of sight like George R.R. Martin’s did), took part in a panel on writing science fiction and fantasy scripts, and sang, as part of the “filk” programming (filk music is the SF/fantasy equivalent of folk music) The Road Goes Ever On, a song cycle of poems from the works of J.R.R. Tolkien set to music by Donald Swann (of famous music-hall duo Flanders and Swann).

But as usual, I regret not attending more panels of all sorts, including science panels. Because the line-up was impressive: So what does WorldCon have to offer writers? Plenty. Here are just a few of the panels at this year’s convention: “The Future of Food,” “Toxicology 101: Everything You Know is Wrong,” “So You Want to Discover the Higgs Boson?”, “Microbial Residents and Hitchikers,” “The Next H1N1,” “NASA and the Future of Space Exploration,” “What Energy Sources are Sustainable?”, “String Theory for Dummies,” “Latest News from Astronomy,” “Apollo 13: The Longest Hour,” “Mars Desert Research Station,” “Curiosity: The Mars Science Laboratory,” “Ceres, Our Nearest Dwarf Planet” and “The ‘Other’ Space Telescopes.”

And that’s just a small selection!

Of course, there’s lots more to do. There are readings and small get-togethers with authors (called Kaffeeklatsches or Literary Bheers, depending on the beverage available), the masquerade (where the costumers show their stuff on stage), the art show (where the work exhibited includes some from the top illustrators in the field) and the Big One, the Hugo Awards, whose winners are nominated and then voted on by the members of the convention.

Notable winners this year included Montreal writer Jo Walton, whose novel Among Others (Tor) won the Hugo for Best Novel, Neil Gaiman, for his Doctor Who episode “The Doctor’s Wife” (Best Dramatic Presentation, Short Form), George R.R. Martin, who accepted on behalf of Game of Thrones, the HBO series based on his novels (Best Dramatic Presentation, Long Form), and best of all from my point of view, Betsy Wollheim, who won the Hugo for best editor (long-form). Betsy, who has been an editor for 37 years, is also the publisher of DAW Books along with my editor, Sheila Gilbert.

WorldCon is always a fantastic (if exhausting) event, a bit like trying to drink from a fire hose: you just can’t take it all in. There’s only one solution to that, of course: go to the next one.

The 71st World Science Fiction Convention, LoneStarCon 3, will be held next Labor Day weekend in San Antonio.

See you there?

August 25, 2012

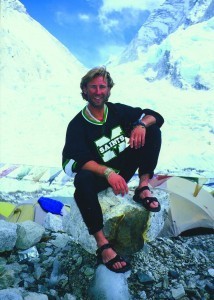

Saturday Special: Dave Rodney – From Yorkton to the Top of the World

(I wrote this feature during my recent short-lived stint as an editor for Fine Lifestyles magazines. It was supposed to be the cover story for Fine Lifestyles Yorkton , but I can’t see any sign Fine Lifestyles Yorkton made it off the ground. It did run in Business Saskatoon .)

Dave Rodney has twice stood atop Mt. Everest, the first Canadian to do so more than once. International keynote speaker, documentary producer, author, adventure guide, educator and humanitarian, he was recently re-elected for a third term as MLA for the constituency of Calgary-Lougheed, and named Associate Minister of Health for the province of Alberta.

And it all started in Yorkton.

Born in Mankota, Rodney was in Grade 1 at St. Paul’s Elementary School in Yorkton when he admired a painting his grandfather had of an alpine scene, wondering what the world would look like from the top of one of those mountains. That wonder planted a seed that would bear fruit on Mt. Everest three decades later. In Grade 5, Rodney’s class went skiing—and Rodney discovered something else he liked about alpine life.

But school days in Yorkton sparked more than just an interest in mountain climbing. He remembers his Grade 9 English teacher asking, “Who will write a book? Who will make a film? Who will become a politician?” Rodney found himself raising his hand several times over. And his Grade 10 social studies teacher impressed him with the comment that “government, when done well, is one of the most important ways to effect social change.”

“We had incredible educators and role models at SHHS,” Rodney recalls. “We were taught about finding out what our mission, our vocation, our calling in life truly is—and to determine what skills and expertise are required, then go out and get them.”

Teaching and climbing

Rodney considered both law and medicine, but wasn’t convinced either was his true calling. From a former vice-principal he sought the name of the headmaster of a school in the West Indies that the Sacred Heart student council had raised money for, and at the ripe old age of 20 spent a year working full-time as an educator on St. Vincent Island. “Living in a postcard,” with a fulltime job, Rodney realized “the world really is your oyster”—provided you work to make it so.

Returning home, he obtained his B.A. and B.Ed. from the University of Saskatchewan, then moved to Calgary as an educator. Over the next few years he taught at several different kinds of schools. “And all this time I was climbing mountains.”

His twin skills of teaching and mountaineering came together perfectly in 1997. A Canadian software group wanted to be involved with a joint Canadian/American Everest expedition, and the climbers realized they needed someone who knew both education and climbing. They called Rodney.

“I was on sabbatical, and since I finished my classes early, I had enough time left over to go on an Everest expedition (which takes three months). I had just climbed the highest mountain in the world outside the Himalayas [Mt. Aconcagua in Argentina], so I was acclimatized.”

Rodney created a new interactive website, Adventure Everest Online, “the first of its kind in the world, copied every year since—which I choose to take as a compliment, rather than as form of copyright infringement,” he says with a laugh.

He created a curriculum offering a lesson a day for Grades 1 to 12, posted a daily expedition update, and corresponded with students from around the world.

“What that experience showed me was that even though I was only a support team member, it wasn’t an impossibility for a person like me to assemble the right type of team and end up on top of the world.”

First Saskatchewanian on Everest

Two years later, he did just that, finding investors to finance an expedition that made him the first—and so far the only—Saskatchewan person to summit Mt. Everest. (He jokes that it’s not all that different from the prairies. “In the wintertime around here it can easily be forty below with howling winds, plus snow and ice. Bend it vertical, and that’s Mt. Everest!”)

He adds, however, that you’d also have to suck out two thirds of the air, multiply the ultraviolet radiation by 10, and throw in rock falls, avalanches, three-kilometer vertical drops, and many forms of altitude illness. Everest can kill you in many different ways, he says, and one member of his 1999 expedition, Michael Matthews, did not return from the mountain.

It’s a grim reminder that there is still nothing commonplace about climbing the world’s highest peak. “Of every 11 people who attempt it, only one gets to the top,” Rodney notes; when he climbed it, there was one death for every five summiteers. But in 2001 he reached the summit a second time, the first Canadian to do so.

It’s a grim reminder that there is still nothing commonplace about climbing the world’s highest peak. “Of every 11 people who attempt it, only one gets to the top,” Rodney notes; when he climbed it, there was one death for every five summiteers. But in 2001 he reached the summit a second time, the first Canadian to do so.

Rodney parlayed his Everest success into professional speaking engagements around the world, as well as books, documentaries, and international adventure guiding. On treks to the Mt. Everest base camp, he’d thank his Sherpa friends for helping him achieve his dream, and ask them about theirs. Reserved and polite, they wouldn’t answer; but as he returned year after year he earned their trust (along with the nickname “Sherpa Dave”).

They told him they dreamed of their children being able to get other kinds of jobs than as climbing Sherpas or helping people on treks. In response, Rodney started the Top of the World Society for Children. “For over a decade now we’ve been sending Sherpa kids to school and to post-secondary education,” Rodney says. “The Sherpas have made a huge positive difference in my life. I hope that we’ve been able to give back a little bit through our foundation.”

Provincial politics

Giving back is also the motivation for Rodney’s tackling of a metaphorical mountain, Alberta provincial politics. “I was strongly encouraged by all sorts of people—educator friends, community leaders, audience members who had heard me speak—to run. I was told I’d be supported if I ran for mayor or as an MP, but I thought I could contribute most to the ministries of provincial jurisdiction.”

When a seat opened up in southwest Calgary, a former MLA asked Rodney if he’d consider running to fill it. He won the nomination, and then the election. He’s been re-elected twice since. “It is such a thrill to help individual constituents every day with whatever their issues happen to be, whether they’re students, seniors or anyone in between,” says Rodney.

He’s “humbled and proud” that he’s had more private member bills passed than any other MLA in his time. He’s particularly proud of The Smoke Free Places Act, the Physical Activity Income Tax Amendment Credit, and the April Alberta Get Outdoors (GO) Weekend—which reminds people that “after a long cold winter, the middle of April is a perfect time to get outside and go for a walk, golf, ski, visit the farm, or adventure in our forests and on our waterways.”

As the newly minted Associate Minister of Health, says Rodney, “It is my honor, obligation, and duty to create the environment in which it is more attractive and easier for people to do what’s best for them. What I want to do is work with all sorts of groups across the province to encourage individuals to choose what is best for their physical and mental health.”

Family life

But the most important thing in his life is his family. He and his wife, Jennifer, have two children: Dawson, four, and Evan, two (and a puppy named MacGyver). “I want to be the best husband and father I can possibly be.”

From the flatlands of the prairies to the top of the world, from schoolteacher to mountaineer to MLA, Dave Rodney’s life has been an extraordinary journey.

But, he says, “I will forever treasure the fact that I was raised Yorkton, Saskatchewan. Some of the finest people on the planet live there, including my parents.”