Days of future past

Sometimes people ask me why I like to write about science. There's all sorts of fancy-schmancy reasons I could come up with about the importance of science to modern society and the wonders of the natural world and the joys of intellectual stimulation—but the truth is, I write about science because I grew up reading science fiction.

Sometimes people ask me why I like to write about science. There's all sorts of fancy-schmancy reasons I could come up with about the importance of science to modern society and the wonders of the natural world and the joys of intellectual stimulation—but the truth is, I write about science because I grew up reading science fiction.

And you know what? That would have warmed the cockles of Hugo Gernsback's heart.

What's that? You never heard of Hugo Gernsback? Well, you're about to!

Modern science fiction stands primarily on the shoulders of two writers: France's Jules Verne and England's H. G. Wells. Verne played on the public's interest in burgeoning technological and scientific advances as the 19th century advanced, and told stories of fantastic journeys to the moon, beneath the seas, to the center of the Earth, and even Around the World in 80 Days.

Wells focused less on the future of technology than on the future of society. The Time Machine was a parable concerning future relations between the working and ruling classes. And The War of the Worlds, the first alien invasion tale, was more about the insignificance of humanity in an uncaring universe than the likelihood of life on Mars.

Yet neither Wells nor Verne is considered "the father of science fiction." That title belongs to Hugo Gernsback.

Gernsback wasn't a writer, at least not to start with. Rather, he was a pioneer in the fields of electricity, radio and television. He sold America's first home radio kit in 1904 ($7.50 at Macy's). When government regulation of radio put him out of business, he repackaged the left-over parts as kids' electronics kits. He also founded New York radio station WRNY, where some of the world's first regular TV broadcasts began in 1928.

But he also moved into publishing. In 1908 he founded the world's first radio magazine, Modern Electrics. For a 1911 issue, finding himself short of material, he filled a few empty pages with a piece of fiction, entitled "Ralph 124C 41+: A Romance of the Year 2660." The story was so popular he wrote more, even publishing them as a novel in 1925. As a prose stylist, Gernsback left a lot to be desired ("Bang! Bang! Bang! Three shots rang out! Each more horrible than the last!") But he wasn't worried about style. He used his stories to toss off scientific predictions like one of his electrical devices might toss off sparks.

Microfiche, skywriting, solar power, holograms, fax machines, aluminum foil and a "parabolic wave reflector" (radar) were all part of Ralph's daily life—but certainly not yet part of the daily lives of Gernsback's readers.

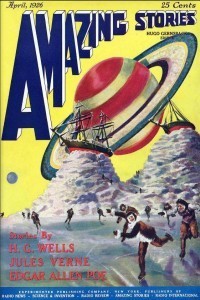

Based on Ralph's success, Gernsback founded a new magazine: Amazing Stories. The first issue from April 1926 (which you can read online, along with many other old magazines, at pulpmags.org) featured old stories by Verne and Wells and Edgar Allen Poe, but was nevertheless, Gernsback claimed in his introduction, "entirely new—entirely different" from other fiction magazines, because it would be devoted to what he called "scientifiction."

He defined scientifiction as "a charming romance intermingled with scientific fact and prophetic vision." His rationale for the new magazine could have been written yesterday: "It must be remembered that we live in an entirely new world. Two hundred years ago, stories of this kind were not possible. Science, through its various branches of mechanics, electricity, astronomy, etc., enters so intimately into all our lives today, and we are so much immersed in this science, that we have become rather prone to take new inventions and discoveries for granted. Our entire mode of living has changed with the present progress, and it is little wonder, therefore, that many fantastic situations—impossible 100 years ago—are brought about today."

Gernsback saw the new genre as a way of "imparting knowledge, and even inspiration, without once making us aware that we are being taught," and that's exactly how it worked out: many of the children who read Amazing Stories under the covers went on to become scientists, engineers or science fiction writers themselves. Gernsback, as Ray Bradbury put it, "made us fall in love with the future."

Implicit in science fiction is the realization that the future will not be like today, and in both its "Vernesian" (focused on the science and technology) and "Wellsian" (focused on the effects of science and technology on society) strains, prepares us and excites us for—and sometimes alarms and warns us about—what that future may hold.

Hugo Gernsback died in 1967, not quite living long enough to see humans walk on the moon. Science has honored him by naming a lunar crater after him. Science fiction, meanwhile, hands out awards every year for the best new work in the field.

They're called Hugos.

(The image:the cover of Amazing Stories , Volume 1, Number 1, April 1926.)