Roz Morris's Blog, page 116

November 7, 2010

What's in a name? Everything – guest post at SunnyRoomStudio

Today I'm guesting over at Daisy Hickman's SunnyRoomStudio.

Today I'm guesting over at Daisy Hickman's SunnyRoomStudio.

Daisy is a poet and the author of Where the Heart Resides:

Timeless Wisdom of the American Prairie and a tireless explorer

of what it means to be creative – as indeed you will know from the

searching comments she often leaves here. Daisy asked me to write

a piece about names in fiction, so here we go…

The three chambers of fluid, lacrimal caruncle, fornix conjunctiva, canal of Schlemm, choroid, ora serrata. Where are these places? Somewhere under the sea? No, they're right where you are. They are parts of the human eye.

I sense an artistic sensibility in the world of ophthalmology, as though its members are preserving a sense of wonder about what these organs do for us…

Read the rest of the post here

And drop back here tomorrow for a more regular post.

October 31, 2010

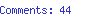

From fragments we build a story – holy cow I'm in a movie with Matt Damon and directed by Clint Eastwood

Apologies for the bragging headline. At the

I was hereabouts

beginning of the year I was an extra in Clint

Eastwood's latest film, Hereafter, starring

Matt Damon. However, I also feel there is

a level-headed, writerly post in it…

I just stumbled across my first review of Hereafter, in The Economist. I am of course, detonating with excitement (although I have to wait until January before it arrives in the UK). But reading the review, I can see for the first time how the scenes I was in fitted with the whole story. (Possible spoiler alert – there's nothing here the press hasn't shared, but if you hate to know anything about a film you want to see, you may want to look away.)

On the set I saw fragments –

Matt Damon going out of the front doors of Alexandra Palace looking upset

Crowd scenes at the London Book Fair

A female character giving a reading from a book on the afterlife

Some twins, one dead

A ghostly boy wandering through the Book Fair crowds

The ghostly boy's twin chasing Matt Damon's character

Derek Jacobi giving readings of Little Dorrit

'Marie has a near-death experience and … writes about scientific evidence for an afterlife… Marcus's twin brother dies in an accident and he goes looking for a psychic who can communicate with the dead… Lonely George (Damon), whose supernatural gift has wrecked his chances with a giggly beauty … goes to sleep listening to Charles Dickens audio books. Indeed, Dickens turns out to be the improbable thread that will bring all three characters to the London Book Fair, where Sir Derek Jacobi is reading from Little Dorrit.'

Suddenly, it's a story.

It reminded me of how I feel when I'm putting a novel together.

To start with, everything is fragments – locations I want to use, characters I know will be important, revelations I feel will be pivotal. Scenes that come in a flash of inspiration. None of them seem to particularly connect. It's like seeing each of them down a telephoto lens and not knowing what's around the edges, how it connects with everyone else.

Seeing the first reviews of Hereafter have reminded me of the fragments I was involved in. And at the time, my WIP was at a very sketchy stage, but now the view has widened. The threads have pulled together. Themes have emerged and resound throughout the story. And it's now making sense.

It's funny to look back and think what scant material I started with.

Do you find this with your novels? Or are you thinking, never mind about the writing, tell us about being in the darn film. Ask me anything you like in the comments. Or watch the Hereafter trailer here

October 24, 2010

How to state the obvious – obligatory scenes in Stephen King's The Green Mile

Sometimes writers have to state the obvious or

put in a scene everybody is expecting. But that's

not a licence to coast. Here's how Stephen King's

The Green Mile makes an obligatory scene into

something special

Stephen King's The Green Mile is a story about the lives of guards on death row. One of the first things it does is set the scene with an execution.

Some writers might coast here – surely the material is startling enough that you don't have to do anything else with it, right?

Wrong.

Here's what The Green Mile does.

It shows two execution scenes, in stark contrast.

The first isn't real, it's a rehearsal. One guard plays the 'condemned' man. He gibbers like a loon and makes lewd last requests. When the other guards throw the switch he writhes and screams with glee. The prison governor allows them to lark about, knowing he is seeing nervous men struggling with a difficult job. He also tries to keep the joking to a minimum because there is a newcomer who needs to be trained. This allows us a way in – in several ways: the prison governor trying not to let the hi-jinks get out of hand, yet realizing the men need to let off steam. The guards themselves, coping with the stress the best way they can. And the new guard, seeing all this for the first time. It also gives the author a licence to dump in as much exposition as he wants. Masterful.

And then he goes one better by showing an actual execution. And how different it is. The prisoner is frightened. The governor handles him with great sensitivity. The guards who were roaring with laughter before are nervous and gentle.

The Green Mile could have gone straight to this scene, relying on the content to speak for itself. But because he put the other one before it, the real one becomes much more appalling. We see how strange and difficult a thing it is to extinguish life.

I often see manuscripts in which the writer assumes there are some things they don't have to explain. Execution is a nasty business – who'd have thought? Surely you don't have to spell that out.

Wrong. For two reasons.

1 One of the things audiences have paid their money for is details of the grisly process. They need to get it somehow. What they don't realize they want is for you to make it way more powerful than they were expecting. So you can't just cruise with scenes like this.

2 In the world of your story, anything is possible. You could have, if you wanted, a bunch of prison guards who were completely blase, and no more affected by executing a man than if they were squashing a fly. You set the rules of the story, what is right, what is wrong, what is difficult and what is easy. And you have to demonstrate them.

So, an execution must be shown and it must be shown to be a difficult job. But The Green Mile turns this into storytelling gold.

Have you got any favourite examples of exposition and obligatory scenes that have been handled with panache? Have you solved similar problems?

October 18, 2010

How to revise your novel without getting stale – take a tip from Michael Caine

Do you hate going over your novel again and again?

Take a tip from Michael Caine and see it as

rehearsing your novel

Some writers hate redrafting. Analysing, dissecting and rewriting their work? A sure way to make themselves hate it.

But if you're hoping to amuse a buying public, your first draft will probably not be good enough. I've written about this before in I had no idea novel-writing was such hard work. Only the superhuman can get everything right on the first go. (I'm talking here about self-directed rewrites, before you show the novel to anyone else. Rewrites instigated by beta-readers, agents and editors are a different kettle of fish.)

So redrafting is a fact of life for writers. If you do it with gritted teeth, that's a problem.

It so happens I love this phase. But I didn't realise why until this week.

The penny dropped when I heard Michael Caine on the radio answering a question about giving natural performances.

He told the interviewer: I use one of the basic principles of Stanislavski. It's called the method. That's not looking at the floor and mumbling and scratching your bum. With the method, the rehearsal is the work and the performance is the relaxation. By the time they say 'action', I've been through those lines 500 times.

This is exactly how I see my writing process.

The rehearsal is the work and the performance is the relaxation

When I am drafting, I am in a continual state of rehearsal. Dissecting, questioning. Inventing new ways to test my story. Taking the characters for little rides outside the story. Digging for fundamental truth. I keep the writing rough while I chop the order of events around, concoct new scenes and drop them in. I always use my beat sheet (see it here demonstrated on the opening of the first Harry Potter novel). My current WIP, Life Form 3, got so darn difficult it needed its own tool, and so I rewrote it as a fairy tale.

Certainly this can be frustrating, particularly when the story is flagging, there are too many unknowns. There's always a stage where I'm convinced I've ruined an exciting idea. That's why it's called work.

But what comes out of it is intensely creative.

Ready to roll

There comes a day when I feel I understand, with a big U, fanfares and fireworks. I know what the characters want in each scene, what they show other people, what they're hiding. I know the character of the book – its world, its struggles, what voice it has. I am confident the reader's heart rate will soar in the right places.

That's when I'm ready to relax and tell the story properly – with the final, in-depth rewrite.

Final draft is the performance

Performance. You know what I mean. If you're a writer you have an urge to perform in prose. You can't just dash off an email to a friend, a comment on someone else's blog, a report for work. Even a note to the milkman will always be a bit of a song and dance. Words are never just words, they are indelible. That's what we really enjoy, right?

My final pass is the performance – the language, style, voice. With all the work I've done, I'm ready to grab hold of the reader and show them something special.

Part of the problem with revising is that you get stale. But if with each pass you are building something richer and better, it gets more exciting, not less. Crucial to this is to keep the text rough until everything is place. Then you can give yourself something to look forward to – telling the story. And isn't that what it's all about?

Are you a method writer? How do you motivate yourself through redrafts?

You can read more about my beat sheet and other revision tools in Nail Your Novel – Why Writers Abandon Books and How You Can Draft, Fix and Finish With Confidence, available from Amazon.com or outside the US from Lulu

Thank you, Tea, Two Sugars, for the picture

October 15, 2010

Looking for a NaNoWriMo buddy? Find one here

Who out there is trying to nail National

Novel-Writing Month? You don't have

to do it alone

You don't have to write your 50,000-word novel alone. Thousands of people out there are waiting to share your pain, to thump you on the back when needed and on the backside when that's needed too.

(If that's double-dutch, click here to find out what NaNoWriMo is all about )

If you're trying to nail NaNoWriMo and want to hook up with more buddies, there are a lot of them right here, reading this blog. So add your details and any links in the comments. Say as much or as little about your NaNo novel as you wish – although I'd love it if you'd say a little about the novel you're hatching. And let's meet new NaNowers (er, is that a word?)

Proper post coming very soon!

Thank you, Gorbould on Flickr, for the picture

October 10, 2010

How to write presidents, kings, queens and superstars

Characters with immense talent or power often feature in stories,

but they can be unknowable, remote and clichés. How can you

dig under the surface and make their star power come alive?

I really, really like Madonna, although at first I didn't at all. Like most serious teenagers I couldn't be bothered with mere pop-squeaks. Then came Live Aid. Her love of what she was doing rocked the rest of the performers right out of the arena. She made me enjoy something I didn't even want to watch. After that, I began to get interested, although I didn't think much of her music. But even that got better. I watched with mounting respect as she made the best of her ordinary voice, got better songs and put on eye-popping shows. You can definitely call me a fan.

However, much as I admire her grit, energy, perfection ethic and willpower there are certain things they won't bring her. For instance, acting ability.

I know zilch about acting, but it looks to me as though her nature will not allow her to be an actress. She cannot let herself be vulnerable or tolerate someone else being in control of her emotions. She will not, ever, show that someone has rattled her. But she makes a heroic effort. She has persevered with acting earnestly and diligently, sometimes in low-profile films, determined to conquer this form.

Her blind spot is the fighter inside her that will not lie down, even if she wants it to. And of course this makes her even more formidable – and puts her in a class of her own.

So what's the writing point here?

Sometimes we have to write characters who seem untouchable. People who run vast companies or kingdoms. Presidents, dictators, princes, superstars.

You can show they're just like you and me. Try what Blake Snyder, in Save The Cat, calls 'the Pope in the pool' – a scene from a thriller where the heroes visit the Pope at the Vatican. They find him in the swimming pool, doing his morning laps. The audience was probably expecting a ho-hum scene of robes and a throne, but they got His Holiness in his bathing suit.

That's endearingly ordinary, but these characters are usually not ordinary. How do you show that? The brilliant tactical brain, the fearless conqueror, the boardroom velociraptor? Fleets of helicopters, henchmen and gold-plated mansions? That can be a bit sterile. Is there a different way to show their special qualities, what it was that made them claw their way past most other mortals?

There is. Show the problems those qualities create for them. Show how their lives aren't perfect, and there are some things they can't do because of it. Show Madonna and her unconquerable pride.

Story prompts

Is there something they can't have? The cliche is that the uber-successful have sacrificed families and friendships. What about an unattainable dream that they keep failing at?

How are their strengths also a flaw? Are their advisers always trying to protect them from their ambition, or clearing up the damage afterwards? What goes on behind closed doors? Imagine Madonna's people, trying to hint that perhaps this album doesn't need another song about how hard fame is? Might it even tip into crisis, like King Lear with his abdication, a final act of hubris and ego?

In some ways princes, presidents and superstars are like everyone else. In certain, special ways they are a breed apart. Find both of those dimensions, slot them together and you make them really come alive.

Have you got a favourite superstar character, in fiction or even the real world? Why do they work so well?

Thank you, Code_Martial, for the picture

October 3, 2010

NaNoWriMo starts right here, right now

November is National Novel-Writing Month, when writers everywhere will handcuff themselves

to their keyboards and aim to get a 50,000-word draft finished in 30 days. Apart from clearing

the diary for November and creating a big Do Not Disturb sign, what can you do to prepare?

And is it even possible?

First of all, do established writers do this or is it just a game?

Certainly NaNoWriMo is not just an exercise. Many established writers use it to get their first drafts done. Novelist Sara Gruen wrote her New York Times #1 bestseller Water For Elephants one NaNoWriMo. What you start in NaNo can go on to great things – here's a list of all the NaNo novels that have made it into print.

How do you do it?

I've never done NaNoWriMo because other projects have got in the way, but I have written a lot of novels to tight deadlines – 50,000 words in two months. And not just first draft, but revised and ready for a publisher to see. It was effectively two NaNoWriMos back to back, which I did several times. Here's how I did it (my 7 top tips to nail NaNoWriMo).

I have several friends who are NaNoWriMo winners. Here are their tips. And the key to success is not just what you do in November, but what you do NOW.

Prepare your story

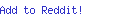

Zelah Meyer is a NaNoWriMo powerhouse, having consistently delivered 50,000 words for the last five years. Some years, she even lost a week because real life inconveniently got in the way, but even so, she sailed past the finish line. This year she's hoping to finish the first draft of her trilogy.

Zelah (left) says: 'Do a rough brainstorm beforehand of where you want to take at least the first 5,000 words or so. I call it plot scaffolding and I'll often talk to myself on paper about what could happen and where the story could go. I find it helps to know that so that I can avoid writing myself into a corner – but everybody works differently!

Zelah (left) says: 'Do a rough brainstorm beforehand of where you want to take at least the first 5,000 words or so. I call it plot scaffolding and I'll often talk to myself on paper about what could happen and where the story could go. I find it helps to know that so that I can avoid writing myself into a corner – but everybody works differently!

'I ask myself a lot of questions such as "Why does nobody know that he isn't really the lost prince/company CEO/etc?" I use the ideas I have to flesh out character back story and sometimes that will give me ideas for the plot.

'If I decide that I need to go back and add in a scene, I'll do that – but I never rewrite one. Instead I have a second document that I keep open called Corrections. There I make notes of changes I want to make in the re-writes and then continue as if I'd already done them.

'I also find it helps to have a third document for any names I need to keep track of. This saves me from wasting ages scanning back through thousands of words trying to find out which town the characters were heading for or what you called the hero's aunt.'

In real life, Zelah is an improvisational performer, and her experiences on stage have strengthened her approach to storytelling. 'I ask myself: "If I were in the audience, where would I want the action to go now?" and "Which character do I want to hear from now?" Also, everything that is said changes you – both the person saying and the person listening. Everything evokes some kind of emotional response and that colours how things happen from then on.'

Prepare your targets

Gareth Ryder-Hanrahan (left), another NaNoWriMo veteran, says: 'My one tip is stick to your daily wordcount no matter what – 1,600 words a day even if you've been run over by a steamroller. Nothing's more disheartening than an impossible deadline,'

Gareth Ryder-Hanrahan (left), another NaNoWriMo veteran, says: 'My one tip is stick to your daily wordcount no matter what – 1,600 words a day even if you've been run over by a steamroller. Nothing's more disheartening than an impossible deadline,'

Zelah's keen on statistics too. 'I create a spreadsheet for the 30 days of November with how many words I aim to write on each day. I give myself a contingency of around 5,000 words.'

Prepare your research

If you go and look something up on Google, do you stop there? No; an hour later you can still be happily cyber-faffing. So do all your Googling, Wiki-ing and forum fact-finding before November. Don't burn through your writing time by looking stuff up. If necessary, put a keyword in the text like [factcheck] and start a file for queries you will Google in December.

Find support

You don't slog through NaNoWriMo on your own. That's one of the beauties of it. The NaNoWriMo website is, of course, essential, and you'll find hashtag communities on Twitter, and bloggers who will be wearing NaNo badges and blogging if they have any fingers to spare.

Ann Marie Gamble, another winner, says: 'The single best non-official resource I used last year was Doyce Testerman's day-by-day blog posts. He described exactly what he was going through so I could think, ah, everyone feels like they are choking on Day 11 – it's not just me being pathetic. Plus he has a wife and kid, so his coping strategies are more accessible to me than those of the college students in the local NaNoWriMo groups.'

Remember it's a first draft

NaNoWriMo is about turning off your inner editor. If your draft sucks that doesn't matter. All first drafts suck.

It is also about a definite goal. Ann Marie says: 'Keep your eyes on your prize. NaNoWriMo is a chance to build writing habits and experience in finishing a piece. Don't get sidetracked by questions of quality, plausibility, readability etc. Let your pen fly during this intense month and analyse later.'

Zelah says: 'When I'm actually working, I remind myself that I'm not striving for perfection at this stage. I have a strip of paper saying "Quantity not Quality" taped to my monitor.

The message is, prepare, prepare, prepare.

your story

your research

your targets

your support groups

And that, my friends, is why NaNoWriMo 2010 starts now.

With all that sorted, just one thing remains. Simon C Larter (left) of the blog Constant Revisions says: 'How do I convince my wife it's okay for me to spend so much time writing?'

With all that sorted, just one thing remains. Simon C Larter (left) of the blog Constant Revisions says: 'How do I convince my wife it's okay for me to spend so much time writing?'

Are you doing NaNoWriMo 2010? How are you preparing? Is it your first time? If you've done it before, do you have any tips? And if NaNo requires you to ramp up your writing routine, how, like Simon, will you convince your nearest and dearest to indulge you? Share in the comments

You can find tips for researching, outlining and what makes a robust story in my book, Nail Your Novel – Why Writers Abandon Books and How You Can Draft, Fix and Finish With Confidence. Available from Amazon.com and outside the US from Lulu

September 27, 2010

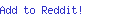

What characters hide – The double life of Isobel

How to create a three-dimensional

character – consider the many people they are

I can never resist a note on the pavement – and as I walked to the Tube this was waiting for me. For those receiving this post in pictureless email, what I found was a card that says Dear Isobel, Happy birthday! With love from Izzy xxx Multiple personality disorder? Double life?

This may seem far fetched, but she might easily be Izzy among friends, while she conquers the world with the stern face of Isobel. Or she could be well-behaved Isobel to her family, a wilder Izzy elsewhere. (By the way, if you like notes on the pavement too, you'll love Found Magazine.)

We all, to an extent, keep parts of our lives hidden. People aren't the same all the time, with everyone. And characters shouldn't be either.

Colleagues don't know what we are like under the professional mask – and sometimes it's quite a dense mask. Close friends don't know the personality that comes out when we're in work mode – perhaps fighting fires, selling door to door, standing up in court to defend a client, ruling the kingdom. Children don't realise their parents are so interesting, and parents don't realise their children are so complex, curious or independent.

*Imagine Isobel's friends wrote a list of what they know about her. Would it be the same as a similar list made by Izzy's friends?

A three-dimensional character has different sides – even if they think they have not got much to hide, and even to people who see them all the time. Those who know Isobel might be surprised to meet Izzy and vice versa.

*When is she more Izzy and when is she Isobel? How do the two halves dress? What do they talk about? What kind of people do they mix with?

Chemistry

As well as the Izzy/Isobel role split, there is chemistry to consider. Perhaps Izzy emerges when a new person arrives – or departs. The infamous Big Brother may have been panned for some of its crasser experiments but one of the most interesting things it demonstrated was the complex dynamics of personal chemistry. I particularly remember in the first UK series a housemate who looked so shy she was invisible but came right out of her shell once another character was evicted. If someone new arrives in the story, such as a potential lover, he (or she) might really bring Izzy alive.

*Who brings out Isobel and who brings out Izzy?

Conflict

These different faces may be a juicy source of conflict – and might even be the entire story. The double life may be overt – perhaps Isobel works under cover. In a less adventure-oriented story, perhaps she is given a choice that creates internal conflict – one half of her wants to take the safe job offer and the other yearns to drop it all and follow her dream – here's my piece on how this drives the entire story in Richard Yates's Revolutionary Road. Or maybe Izzy is a less mature incarnation and perhaps Isobel now wants to be taken more seriously – Deborah Harry instead of Debbie.

Isobel might not even know she's hiding Izzy. Another reality TV series, Faking It, would take a fine art student and challenge them to learn how to be a graffiti artist, or a naval officer and send him to become a drag queen. They were often suspicious of the new world they were pitched into – or they even despised it. They were made to do things that challenged their ideas of what they valued and who they were. They had to wake up sides of themselves they had never expressed before, indeed had repressed. But bit by bit, there was something inside them that embraced this new life. They relearned who they really were.

This kind of change is immensely satisfying. Is Isobel liberated to become Izzy?

*If Izzy wrote a note to Isobel at the end of the story, what would it say?

Does your main character have a double life? And have you found any interesting writing prompts in notes on the pavement? Share in the comments!

September 19, 2010

How to write descriptions vividly and well

How do you develop a good

descriptive style? Do you have to use fancy language to write

novels well?

I've had a question from Integral, who was commenting on my recent post Writing for your day job is nothing like writing a novel. 'One of the biggest problems I face when trying to write prose is that my vocabulary is too limited to paint scenes vividly. I'm a copywriter and I trained as a journalist, and having a fairly limited vocabulary hasn't been a particular disadvantage so far. I simply need to be able to write clearly and concisely. But when I come to write prose, I really struggle to find the right words to use. What's more, my metaphors and similes seem forced.'

In a novel, more is expected of the prose than a straightforward account. The reader has an inner cinema to light with imagery, a poetic ear to beguile. As Dave said in a comment on that same post: 'the difference between writing fiction and writing other types of documents is like the difference between talking and singing'.

Developing a descriptive style takes time, and quite a bit of trial and experimentation. There are books that can help nudge you to widen your vocabulary. I use Roget's Thesaurus and I'm also rather interested in The Describer's Dictionary by David Grambs.

A lot of writers read poetry to tune into what language can do when cut free from its functional bonds. I return constantly to William Golding's novel Pincher Martin. Here's the opening, in which a sailor has been pitched overboard:

'There was no up or down, no light and no air. He felt his mouth open of itself and the shrieked word burst out. "Help!" '

So what makes a good description?

Integral mentioned metaphors and similes. These are often overused by writers who are grasping for a more elaborate style. There is nothing wrong with them if they're fresh and well deployed, but there are many more ways to create arresting prose.

Look at that description from Pincher Martin; it does not contain a metaphor or simile, yet reading it is like bypassing language and mainlining pure sensation. It is observant, truthful, unusual.

Notice also that it is not laden with adjectives or adverbs. Or unusual words – except for 'of itself', but that is an artefact of when the novel was written rather than an obscure construction. The power of this description is all in what Golding notices about drowning – that is unique and he says it plainly.

To develop your descriptive instrument you need to be on a constant quest to be more daring, flexible and different.

Not just language

Although a writer's style is what we notice most obviously on picking up a novel, a good novel is more than pretty prose. There's characterisation, structure, plotting, themes, the way you use your setting and so on. Going more poetic, there's story metaphor.

In Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre, there is a strange screaming presence in a far-off attic. This represents Jane's repressed, passionate nature (and is also a darn good mystery). In Daphne du Maurer's Rebecca the first Mrs de Winter is a ghost who represents second Mrs de Winter's profound feelings of inadequacy. Although Bronte and du Maurier have voices that are full of passion and mystery, those stories would still work if they were told in a much plainer style.

Last but not least

In my novels, the language is what I hone last, when everything else is ticking along nicely. Only then do I worry about the imagery and descriptions. And that takes a lot of sweat. I think carefully about each line, taking several runs at each sentence before I'm happy it does what I want – and that it is truthful and mine.

Your voice is you

And this is my final point; your voice has to be you (I've written about it here in How to develop a strong writing voice). Work out what your literary strength is, and learn to use it well. It might be your sense of fun, mystery or mischief – like JK Rowling. Or fun and irony, like Jane Austen. If dense poeticism doesn't come naturally to you, there's nothing wrong with simpler language. Your stories can still be resonant, relatable, entertaining and universal. If clarity is your strength, build on that. It never did Ernest Hemingway any harm.

Good writers are great observers. To write description well, learn to notice the unusual, and to say it in an original way.

September 12, 2010

Should you use real life in your novels?

How do you make good stories out of real life?

S

hould you change things?

This week, a picture popped into my inbox. It's a frame from the manga graphic novel Cloud 109, the latest WIP by artist Peter Richardson and writer David Orme. Peter sent it because he's put me and Dave into the background as a cameo.

This is something arty folk do regularly, of course; we're forever using each other as cameos and walk-ons in our stories.

But this is only for cameos. Not main characters.

In fact, this topic has been hot all week. Mysteries writer Elizabeth Craig started it when she asked, should you write about people you know? Non-writers assume that everything we write is recycled from our own lives – but they don't realise how much invention is added. The debate carried on on Twitter, where the consensus from writers was this: sometimes real people go into novels, but if they are to play major parts, they require a lot of tweaking. What comes out is not necessarily that similar to the raw materials that went in.

No character from real life, however remarkable, is going to be completely suitable just as they are.

And that's just when they start off in the story. If characters are to be explored in any great depth they will probably – and should – evolve as the story goes. They may surprise you, develop a will of their own – that oft-repeated phrase 'the characters took over'. Not only do they do what they want, they go through their own changes which you can't necessarily predict when you start.

To use real life well in a novel, you have to allow everything to go its own way.

This doesn't just apply to characters, but also to events.

I used to go to a critique group, and one week a lady read from her novel about a couple divorcing. There were many scenes featuring bitter arguments. Everyone agreed the characters' distress was plain to see but following it all was difficult. We started to make suggestions that would help us find a way in – so that we could engage with the characters and why they were so upset with each other. There were suggestions to amalgamate two characters, show some of the other person's point of view, tone down the villainous behaviour. Every comment was answered with 'but I can't change that, it's what really happened'.

Really, she was writing the novel as therapy, so telling it exactly as she saw it was the point. Inviting the reader to become involved was not her purpose.

But if inviting the reader in is your purpose, you have to be prepared to change things.

You have to know the difference between real truth and dramatic truth. Dramatic truth is universal, in some ways it is about us all. Real truth is messy, overblown, particular to one situation. For instance, coincidences – in real life they happen all the time. In novels coincidences usually look like lazy storytelling. In real life, people behave in ways we will probably never understand. Real life is a terrible template for a story – it only gets away with it because we can't turn it off.

Truth is stranger than fiction – or, if you're a storyteller, fiction cannot be as messy and strange as truth. In a novel, the reader knows you have made up the events – therefore the events themselves are not as important as what they signify, or their part in a coherent whole. This is an absolute rule, no matter what kind of material you are basing your novel on – and I've helped clients make novels out of truly horrific childhoods, which you might think gave the writer a free pass for the reader's indulgence.

If you're basing a story or characters on real life, don't get hung up on what really happened. You are not giving evidence for the police. When you write fiction, no matter what you are making it out of, you cross a line. Telling the real truth isn't your job. Telling the dramatic truth is.

If you're going to write about real life, be prepared to let it change to make a better story.