Roz Morris's Blog, page 111

April 24, 2011

How to make your most ordinary scene interesting

Having a cup of tea on the way somewhere

Some scenes crackle off the page as we write them. Others fill logical gaps or give us information, but they can be the dullest scenes to write. How can we liven them up?

I'm a big fan of giving scenes in novels a purpose, but in some manuscripts I come across scenes that are all purpose and no soul. I can see the writer thinking – ho-hum, here's where I introduce the main character's parents over tea, here's where they've got to be in the car going somewhere, here's where he explains a set-up that we need or nothing else will make sense. The writer's weariness slumps off the page.

But elsewhere in the novel, the tension is beautifully done, the characters spring into three dimensions as living, feeling people, with things to hide, issues that are at odds with some of the other people.

Wow, what just happened? It's as if the book has come alive.

No. The writer has come alive.

The reader knows you were bored

When I point out that some of their scenes were flat, the writer usually says they had a hard time writing them. But, they say, I have to get those bits in, don't I?

Going from A to B in a car, the Iron Man way

They're right in a way. For a story to make sense you do have to convey a certain amount of information, background, and there are logical gaps you have to bridge.

But you don't need any scene that you're bored by. Because the reader can tell your heart wasn't in it.

What I do

When I get to a scene that makes me feel this way, I rethink. How can I get my obligatory information across in a way that entertains me? I play a few improv games to make the dialogue snap, I mess around with the location or other things the characters can do until I hit on something that makes it all wake up. (You'll find some of them in my book, Nail Your Novel – Why Writers Abandon Books And How You Can Draft, Fix and Finish With Confidence).

Or make them say the opposite

Another thing you can do if you have an obligatory conversation is make the characters say the opposite of what they needed to say.

In Hitchcock's film of The 39 Steps, there's a scene where the hero, Richard Hannay, is in a hotel room with the woman he's handcuffed to. They're lying on the bed and she's obviously going to ask him if he's really a murderer. And he's got to explain. I was keen to see how the writers would tackle this because -

1 – we're going to get a lot of explanation

2 – it's all stuff we've already seen, yet he obviously has to tell her.

How in holy were they going to keep us interested?

Here, roughly remembered and greatly truncated because I didn't think to write it down at the time, is how that bit of the dialogue went:

She: I've been told murderers have terrible dreams.

He: Only at first. Got over that a long time ago. When I first took to crime,

I was quite squeamish about it….

She: How did you start?

He: Quite a small way, like most of us. Pilfering pennies from other children's lockers at school… a little pocket picking, a spot of car pinching… Killed my first man … In years to come, you'll be able to take your grandchildren to Madame Tussaud's and point me out.

She: Which section?

He: It's early to say. I'm still young … You'll point me out and say, "if I were to tell you how matey I once was with that gentleman, you'd be… "

And so on. He didn't explain how innocent he was. He went ludicrously over the top and claimed he was on his way to being the grand-moff master-criminal. Far from being a plodding piece of exposition, it's a wonderful character piece that makes the characters trust each other a little more.

In a good story we're interested in every scene. So every time you find yourself wearily thinking 'I've got to get this bit in' or 'they have to go here or say this' wait, think and brainstorm. Turn off the autopilot and find a way to write it that excites you.

Do you have any tips for obligatory scenes? Or examples of scenes where writers have found a great way to liven them up? Share in the comments!

April 20, 2011

Pretty, precious, purple – talking prose with Victoria

What makes good writing? Victoria Mixon and I are fearlessly grappling with this question in this week's editor chat, over at her wood-panelled lacy writing nest. Highlight? Victoria threatens to shave her head and move to Tibet Om your way over and see if you can stop her…

What makes good writing? Victoria Mixon and I are fearlessly grappling with this question in this week's editor chat, over at her wood-panelled lacy writing nest. Highlight? Victoria threatens to shave her head and move to Tibet Om your way over and see if you can stop her…

April 19, 2011

I've had near misses with agents and publishers – should I self-publish?

I had this very interesting comment from Paul Gresty about my interview with John Rakestraw at BlogTalkRadio, and it's typical of questions I've been seeing a lot of authors wrestling with. What follows is just my opinion as an author and freelance editor, and may be typical only of the UK publishing market, but here goes.

I had this very interesting comment from Paul Gresty about my interview with John Rakestraw at BlogTalkRadio, and it's typical of questions I've been seeing a lot of authors wrestling with. What follows is just my opinion as an author and freelance editor, and may be typical only of the UK publishing market, but here goes.

Paul: You talked in the interview about writers who have had near misses with agents. A few times now, the agents who've read my novel have said: 'This is really good, but we can't see a major publisher going for it. Try finding a smaller publisher of literary fiction for it, and send us whatever you write next.' At the same time, smaller publishers, with whom I've published bits and pieces before, are saying, 'We don't have the means to publish a new book right now'.

I know a number of writers who have excellent, interesting novels that are not getting published. Perhaps they cross genres, or they're too edgy to be literary and too intelligent to be genre. In all likelihood if those writers were submitting those same novels to the market 5 or 10 years ago they would have landed a publishing deal. But publishers don't want them any more.

My agent says he's had plenty of situations in the last few years when editors have adored a novel by one of his clients, have recommended it for publication and had it rejected by the marketing department. So these novels were definitely good enough. But the marketers didn't want them.

Why?

Publishers don't sell to ordinary readers

The major publishers sell to book stores, and they want to make bulk sales to chains. They want titles that will sell in quantity. Not something 'interesting' that will sell one or two copies per store.

Meanwhile, smaller publishers are inundated with submissions and can only afford to publish a few titles a year. This is because there's a lot of work in bringing a manuscript up to standard and it is simply impossible for a shoestring staff to handle more than a small number.

Paul: Perhaps the solution is to publish an ebook?

That seems to make perfect sense. While you may not shift very many copies in your town or even your county, worldwide you might find 15,000 people who want to read what you write. Providing you can reach them – and the internet is the place to do it. Some small publishers are testing the water by epublishing titles first, and then if sales go well they produce a print version. But again, you have to land on their desk before they hit their quota for the year. How lucky do you feel?

Paul: On the writing courses I've done over the last few years, I've been advised against self-publishing – 'vanity' publishing, with all the negative connotations. 'It shows that you haven't looked hard enough to find a 'real' publisher,' I've been told. But maybe that's changing. Maybe self-publishing is becoming more legitimate. Is it?

Ooh, this is interesting.

Vanity publishing is not the same as self-publishing. With vanity publishing you pay – usually a lot of money – for someone to print thousands of shoddy copies of your book and then you discover they're not going to sell or distribute them for you. It's usually verging on a scam. With self-publishing no money changes hands until a copy is sold (of course you may spend money on covers, editing etc, but that doesn't usually have anything to do with the self-publishing company).

As for the assertion that if you can't get a 'proper' publisher you haven't earned your spurs…

Many of the people saying that either wouldn't get published now or have never tried at all. I still encounter people who imagine they only have to slip their magnum opus through a publisher's letterbox and they'll be Rowling all the way to the bank.

Take no notice of the stuffy gits at those writing courses. They're well out of date. I bet most of them don't even know what an online platform is, or assume we're all writing undisciplined noodlings about what we had for breakfast.

I couldn't get a 'proper publisher' for Nail Your Novel. I was told it was far too short and there were far too many how-to-write books. It was not needed in the market, apparently. So I self-published. Far from being a flop it's been getting great reviews and sales that have surprised me. I regularly get emails and tweets from people who are genuinely grateful I put it out there.

Catherine Ryan Howard, of the blog Catherine, Caffeinated, self-published her travel memoir Mousetrapped after agents told her it was a good read but hard to place. It's doing very nicely for her – especially in ebook form. (She's got a book coming soon all about how she self-published. I just read an ARC. If you're interested in self-publishing it's called Self-Printed and I urge you to get it.)

Which brings me back to…

Conventional publishers have narrower tastes than the book-buying public. Much narrower.

My agent also says that the pendulum is bound to swing the other way in favour of these maverick, original writers. That's lovely of him, but who knows if it will? Self-publishing makes sense if you've exhausted normal channels and don't want to wait for ever.

The trouble is, as I said on the radio show, anyone can now hit 'publish'. There isn't yet a reliable way for readers to find out which the good self-published books are, especially with fiction. How do you even get noticed?

I haven't got an answer for this. Except…

Let's show those stuffy gits

Self-publishers are now more credible than we have ever been. We must keep that credibility. We must aim for the highest possible quality. That means getting professional help with the editing, proofing and design, so that the book can hold its own against the best of conventionally published titles. (In fact, I'm just revamping the interior design of the print version of Nail Your Novel so that it looks as crisp as possible. Not the content, just the layout and typestyles. When I first formatted it I didn't think I'd be getting it on Amazon alongside the top-selling books in its field. Now it needs to look the part.)

To sum up: Paul, if you're really sure you've done all you can to make your book as good as you can, hit publish.

(Thank you, Oldonliner, for the picture)

What would you tell Paul? Are you another 'near miss' author? Discuss in the comments!

April 18, 2011

Would you cross the road to avoid them? A problem with flawed characters

Characters with major flaws aren't always endearing. Here's how they might scare the reader away

Characters with major flaws aren't always endearing. Here's how they might scare the reader away

Most writers are aware that if their main character is going to change, they have to set them up as incomplete, or flawed, or in need of something.

But I see a lot of manuscripts where they've gone too far. The MC is so abject, feeble, whiney, wussy, miserable, dysfunctional or even bonkers it's a wonder they ever acquired a bipedal stance.

And that usually makes them hard to tolerate.

First impressions count

In the first few pages of a book, we're deciding if we want to spend time with the characters. Although flaws can definitely be humanising and endearing, creating a character like this is such a fine balance. If they're too draining, we'll quietly put the book down.

Yes, there probably are people like this in real life. But do you seek them out? Be honest now. You let voicemail take their call.

The faithful friend solution

Often the writer senses the character is not likable enough. So they give them a faithful friend who is always looking after them, and hope this persuades the reader that something about them is adorable.

This friend has endless patience for the MC's feebleness, unreliability and bad behaviour. They may even give a tough-love pep-talk from time to time. Personally I either want them to take centre stage as they have the more interesting life, or I want to give them a slap too.

But flawed, damaged, incomplete characters can be quintessential drivers for a good story. So how do you build them?

Don't make the flawed character helpless.

Ask yourself: how do they cope? Presumably they need to earn a living, manage a family or keep up with schoolwork. Even people with quite serious problems manage a juggling act where they keep it under control – just about.

Show that. Perhaps they are keeping a high-powered job in spite of being blitzed on cocaine. Or pouring Darjeeling demurely at the vicar's tea party while being tormented by horned demons. Or playing the romantic lead in a drama despite being abused by their real-life husband. Or trying to please their parents who want them to be accountants, but sneaking off to circus practice because that's where their heart is.

People who really have problems paper over the cracks and carry on as if life is normal. Readers love to spot the holes – and they love the plucky, the brave, the fighters. Make them show their hero qualities by what they are already having to cope with – and the reader will love them.

Thank you, Freya Hartas, for the pictures – more of her work can be found at her fab blog Carl Has The Funk

Who are your favourite flawed characters?

April 17, 2011

Structure, creativity, one-click publishing… and the fossil record for our books

John Rakestraw of Unbridled Editor invited me on his Blog Talk Radio show today. John used to be an actor before he became a freelance editor, and we had a great time nattering about fleshing out characters, creativity, where a story starts, the liberating influence of story structure and how to create a story that pulls the reader in.

John Rakestraw of Unbridled Editor invited me on his Blog Talk Radio show today. John used to be an actor before he became a freelance editor, and we had a great time nattering about fleshing out characters, creativity, where a story starts, the liberating influence of story structure and how to create a story that pulls the reader in.

We also waded into the big questions facing writers today. What becomes of publishing if epublishing is as easy as hitting a button? As the classics of the future are written on computer and manuscripts disappear, will there be a fossil record for how our books evolved? And speaking of what is on record and what is not, there's a little chit-chat about ghostwriting and not being able to tell people I wrote the books they loved… Proper post tomorrow, in the meantime – hope you enjoy our natter.

April 13, 2011

Talking characters – Victoria and me

I'm back at Victoria Mixon's for the second part of our weekly editor chats. Last week we hammered out plot. Today the subject is characters. We discussed techniques for developing characters, what makes a character with dignity and depth, whether to use all your research – and my dislike of what some of you call plaid and what I call tartan.

I'm back at Victoria Mixon's for the second part of our weekly editor chats. Last week we hammered out plot. Today the subject is characters. We discussed techniques for developing characters, what makes a character with dignity and depth, whether to use all your research – and my dislike of what some of you call plaid and what I call tartan.

Hey, we're all allowed unreasonable quirks. Take a highland fling over to Victoria's blog and see what it's all about… Thank you, Lee Carson, for the picture…

April 10, 2011

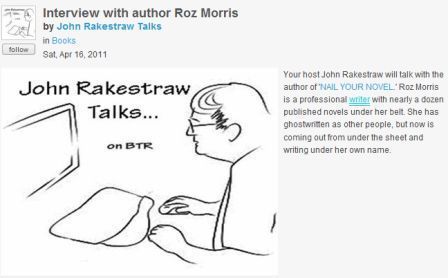

Why the best novels are written on the back of an envelope

Writers, are you daunted by a blank sheet of paper? Here's a remedy

Writers, are you daunted by a blank sheet of paper? Here's a remedy

Do you have special notebooks? I have several. Many of them were gifts from friends who wanted to give me something writerly 'to help with my new book'. The most extraordinary is upholstered in buckskin and inhabited by rough-edged Japanese paper with glints of gold, as though it is recycled from illuminated manuscripts.

It is undoubtedly lovely. But I have used only half a page of it.

When I need to chew over a plot arc or talk to myself about my themes, I reach into the bin for an old cover letter from my contact lens supplier, a delivery slip from Amazon. Or an envelope.

Dave tells me off for never emptying my bin. I regard it not as full but as well stocked. Anyway, he's just as bad. His bin may be clear but beside his desk he has a pile of old printouts, with workings for his WIP, Mirabilis Year of Wonders. Each time he starts a new Mirabilis book, he buys a formal, lined notebook. They remain unused.

Why do we prefer to work like this? Perhaps it's because the first idea is rarely the perfect one. Ideas need to be tweaked, turned upside down and shaken, scribbled out and started again. A scrappy page or an envelope that was already in the bin is not a serious document. It allows you to be rough.

Of course, it's obvious to write notes on the blank side, but I prefer the side with the print on – where the only room is in the spaces between the original dull prose. Somehow this invites my most creative graffiti. My Inland Revenue PAYE coding notice (which was destined for the filing cabinet, not for throwing away) will now probably not be filed for months as it was in the way when I needed to make a research list for my new WIP Echo.

Real creative work goes through a lot of rough stages, and a blank sheet of beautiful paper is way too daunting for this.

I wonder how many posh notebooks are bought by writers' friends and relatives and remain sacrosanct on the bookshelf?

Which do you use? Posh notebooks or scraps from the bin?

April 6, 2011

We can't leave plot alone – first in a series of weekly chats with editor Victoria Mixon

Back in January, Victoria Mixon and I amused ourselves mightily with a couple of rambling discussions about writing and editing – here and here.

Back in January, Victoria Mixon and I amused ourselves mightily with a couple of rambling discussions about writing and editing – here and here.

For those who don't know, Victoria is the author of The Art & Craft of Fiction, A Practitioner's Manual, and her blog was rightly voted one of the top 10 writing sites in the Write To Done awards (in which Nail Your Novel was a runner-up).

We enjoyed ourselves so much in January we decided to do it again, this time with slightly more focus on the core elements of novel-writing. For each week in April we're going to be tackling plot, character, prose and whatever else seems important. As you can probably tell, we haven't firmed up the last topic yet – so if you have a request, get it in now.

Join us over at Victoria's, where we're discussing hooks, conflicts, faux resolution and climaxes – as well as the biggest problems we see with client manuscripts. And what saves the Terminator from being flesh-coloured goo.

April 4, 2011

A not-very-serious post – what's the soundtrack for your novel?

In my post below on starting a new novel, I briefly discussed using soundtracks while writing, and Sally, in one of her comments, asked what the soundtrack was for Life Form 3. As so many of you have said you use soundtracks, I thought it might be fun for us to share them!

In my post below on starting a new novel, I briefly discussed using soundtracks while writing, and Sally, in one of her comments, asked what the soundtrack was for Life Form 3. As so many of you have said you use soundtracks, I thought it might be fun for us to share them!

Here goes. Soundtrack for Life Form 3

Fireflies by Owl City

Music has the Right to Children by Boards of Canada (whole album)

Martes by Murcof (whole album)

Passion by Peter Gabriel (album)

The Sensual World by Kate Bush (just that song)

The Lark Ascending by Ralph Vaughn Williams

Okay, guys – your turn on the decks.

April 3, 2011

From tiny beginnings: how I start a novel

Can you remember what you did when you started on the novel you're working on? If you've finished more than one, do you have a way you like to prepare? Are they always the same or are they different for each project?

Can you remember what you did when you started on the novel you're working on? If you've finished more than one, do you have a way you like to prepare? Are they always the same or are they different for each project?

Last week I wrote about reaching the end of the tunnel and emerging, blinking and relieved, with a finished book. Now, of course, I find myself at the beginning of another. Here's what I do.

I've got a working title for my next novel: Echo. It started as a subject I'd always wanted to explore, then a week ago formed into an idea that demanded to be written. Now I'm quarrying for the beginnings of my story.

This is what I'm doing. I'm hunting around Amazon and LibraryThing to see who else has tackled the subject, getting acquainted with all the various ways writers have handled it so that what I do will be new.

I know what I want the story's atmosphere to be, so I'm delving through the less-familiar albums in my music collection to build a playlist. Some of these will become a soundtrack for important sequences or characters, capturing a vital essence or even just a moment.

At this stage, anything is possible. Ideas tumble out of everywhere. A chance headline seen on someone's paper while travelling on the Tube. A TV programme glimpsed while persuading the DVD to work. A conversation with a friend. A book cover that startlingly would be perfect if it had been designed for Echo.

Each of these could drastically change the way the book develops. This is where storymaking seems like serendipity and fragile chance. As much about random collisions as about research.

And so what I'm doing most, as I stand at the edge of the tunnel, is watching and listening.

Tell me what you do to start writing a novel

(Thank you, Paul Beattie, for the pic) You can find more tips for planning your novel in my book, Nail Your Novel, available in the Kindle US store, the Kindle UK store, and in print.