Roz Morris's Blog, page 115

January 2, 2011

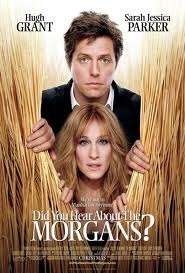

New Year special – writing sins that scupper a story Part 4: Did You Hear About The Morgans?

Weak story links, lazy plotting, wrong point of view, unsatisfying endings… Although Chez Morris we've taken time off from writing, we've seen some DVDs that have roused me to write posts of protest. So, to keep your critical faculties ticking over until life resumes as normal, I thought I'd share them with you in this five-part mini-series. (And yes, beware spoilers…)

Weak story links, lazy plotting, wrong point of view, unsatisfying endings… Although Chez Morris we've taken time off from writing, we've seen some DVDs that have roused me to write posts of protest. So, to keep your critical faculties ticking over until life resumes as normal, I thought I'd share them with you in this five-part mini-series. (And yes, beware spoilers…)

Today: Did You Hear About The Morgans?

Did You Hear About The Morgans? features a couple from New York who are separating. Out one evening to discuss their divorce, they witness a crime and are forced to go to a safe house, in a tiny town hundreds of miles away from the city.

This sounds like a great concept –danger, soul-searching, an unsophisticated town to put the New Yorkers back in touch with what really matters.

Writing sin 1: story delivers on expectations only superficially and not deeply

Did You Hear About The Morgans? delivers on none of the promises, except in the most mechanical way. There are a number of mishaps and small-town oddities, but they seem to operate only to set up superficial and unsatisfying pratfalls later.

There are nominal attempts to get the Morgans involved in the community – Mrs Morgan, who is a real estate agent, helps the doctor to sell his house, and Mr Morgan, a lawyer, helps an ornery old grump to write a will. None of these have payoffs later, or are particularly funny, or – most important – challenge the characters at any personal level. They seem to have been put in only to show that the Morgans had jobs, and to make the community like them. But in a story like this we want the change to be the other way round – the main characters have to grow to like the community and thus have discovered some new values.

Taking the Morgans out of New York didn't force them to act in new ways, so there was nothing gained by doing it. All it seems to mean to them is that they miss their lattes, vegetarian restaurants and the internet. This story is partly a fish out of water scenario – and should be more than simply a way to force characters to spend time together. The setting should be instrumental in the characters' change.

Writing sin 2: wooden characters

This is the central problem. The main characters are wooden. They never discover anything about themselves. It's a story about a reconciled relationship, but we never see how the two Morgans relate to each other now, what they were like at the start, what had gone bad and how it changed.

There are hints at fertility problems and conflict about starting a family, but these look as if they have been flung in in a desperate attempt to press emotional hot keys, rather than being thought through.

The characters also don't live up to the professions the writers gave them. Mrs Morgan ran a company so famous that she was on the cover of a glossy magazine. Mr was a high-powered lawyer. They should have had some corresponding personality traits, such as tenacity, ruthlessness and ingenuity. When people like that are in conflict with each other, particularly emotional conflict, they should become ugly. It looked like nobody wanted to risk making the Morgans a bit nasty. This misses the point of a story like this. If they don't bring nasty traits out in each other at the start, they have no way to mellow at the end.

Writing sin 3: changing the story direction without putting enough work into the new elements This is just a guess, but it looks to me as though Did You Hear About The Morgans? started life as a thriller. Probably a lot of that material was taken out, but the thriller elements that remain (including how the hitman tracks them) are the best honed and have obviously had multiple drafts.

Also, the supporting cast are far better realised than the main characters. Although they have less screen time, each of them gives us a sense of a real person with aims, hobbies and troubles – conspicuously lacking in the main characters.

It looks like the film was rewritten in a hurry, but nobody paid any attention to working through the main characters properly.

Tomorrow: Sherlock Holmes

January 1, 2011

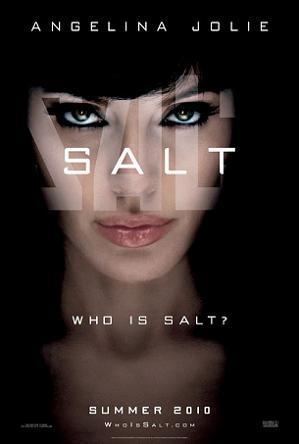

New Year special – writing sins that scupper a story Part 3: Salt

Weak story links, lazy plotting, wrong point of view, unsatisfying endings… Although Chez Morris we've taken time off from writing, we've seen some DVDs that have roused me to write posts of protest. So, to keep your critical faculties ticking over until life resumes as normal, I thought I'd share them with you in this five-part mini-series. (And yes, beware spoilers…)

Weak story links, lazy plotting, wrong point of view, unsatisfying endings… Although Chez Morris we've taken time off from writing, we've seen some DVDs that have roused me to write posts of protest. So, to keep your critical faculties ticking over until life resumes as normal, I thought I'd share them with you in this five-part mini-series. (And yes, beware spoilers…)

Today: Salt

Salt starts well enough. Angelina Jolie's character, Evelyn Salt, is preparing for her wedding anniversary when she discovers she is not a CIA officer but a Russian sleeper spy – and is given an assignment to assassinate the Russian president. Her husband is kidnapped, and she goes on the run. Pretty soon she finds her husband, just in time to see him killed. For the rest of the film, she carries on with her mission, tries to avoid capture and flushes out the real bad guys.

Writing sin 1: breaking the connection with the audience In the commentary the director, Philip Noyce, reveals they cut a scene from the middle, in which Salt is interrogated by the CIA after apparently assassinating the Russian president. She tells them she had to look as though she was going on with her Russian orders because the Russians have her husband and this is the only way to find him. Noyce said he regretted taking the scene out because it 'broke the umbilical cord with the audience'.

With this scene in the film, she is struggling to rescue her husband – and so we are rooting for her. If it is cut out we have no idea what her motivations are, and are left only with the question of whether she assassinated the Russian president or not – a character we have not been made to care about, and an action whose consequences to us are remote and theoretical. For the rest of the film we are wondering whether she is a patriotic American or a Soviet baddie, but again this is impersonal. What the story made us care about at the beginning is whether she loses her husband. When they discarded that from the film, they cut out its heart.

Writing sin 2: bodged ending

The director's commentary reveals there are three possible endings to Salt. In the first ending, she kills her Russian handler (who earlier on killed her husband) – thus ending on a note of emotional closure. The test audience didn't like it – possibly because without the earlier umbilical cord scene it looked glib.

So what did they do instead? In the released version, Salt is unofficially allowed to escape on condition she kills the other sleeper spies – which looks like it's leaving the treadmill on for dozens of sequels. The third ending is a variation on this – a news bulletin hints that the new US president might be another sleeper spy. This is intellectually clever but not emotionally –because we haven't been made to care about the consequences of that. Plus, we can hear that cynical sequel treadmill grinding.

Endings do have to be clever and surprising, of course. But they also have to tackle what the audience most cares about. The revenge killing of the handler would have done this, but only if the thread had been kept.

Tomorrow: Did You Hear About The Morgans?

December 31, 2010

New Year special – writing sins that scupper a story Part 2: Doctor Who, The Runaway Bride

Weak story links, lazy plotting, wrong point of view, unsatisfying endings… Although Chez Morris we've taken time off from writing, we've seen some DVDs that have roused me to write posts of protest. So, to keep your critical faculties ticking over until life resumes as normal, I thought I'd share them with you in this five-part mini-series. (And yes, beware spoilers…)

Weak story links, lazy plotting, wrong point of view, unsatisfying endings… Although Chez Morris we've taken time off from writing, we've seen some DVDs that have roused me to write posts of protest. So, to keep your critical faculties ticking over until life resumes as normal, I thought I'd share them with you in this five-part mini-series. (And yes, beware spoilers…)

Today: Doctor Who Christmas special – The Runaway Bride

In some ways I liked this as Russell T Davies is a slick, economical storyteller. I admire the way he takes a few intriguing ingredients and builds a script. In this case they are the rock that seeded planet Earth when the solar system was being formed, and ancient particles that have been deleted from the universe. I can imagine Davies daydreaming in school physics lessons and thinking 'can't we do something more interesting with the boring old atom?'. He mixes in a bit of showmanship and mayhem at London landmarks (and some soap opera, which I'm a little more doubtful about).

However, although he's good at the big picture, he's slipshod with details – and these undermine the whole story.

Writing sin 1: inconsistency in the pseudoscience We're going to get technical here, so pay attention. Remember the deleted particles? They are attracted to the TARDIS. So one minute the bride, who has been secretly dosed with the particles, is walking down the aisle to get married. The next, she finds herself teleported to the TARDIS – which kicks off the whole story.

But later we meet other characters riddled with the particles who aren't teleported anywhere.

The Doctor makes a flimsy attempt to explain this by saying the bride's stress hormones and endorphins activated the particles in some way, but that's a fudge. It's obvious as a Dalek in your living room what the real reason is – if the other characters teleported too it would cause story chaos (and inconveniently get them out of a tight spot they weren't supposed to escape from).

If you invent science, it has to be robust and stick to its own rules. If you find the rules are inconvenient, you can't add exception clauses in small print. It's particularly bad to bend them with a dose of exposition from a character who miraculously knows everything (and is therefore a get-out-of-gaol card whenever you like). If your pseudoscience rules don't work the way you want, you have to rewrite them at a fundamental level or find another solution.

Writing sin 2: absurdity The big baddie is an alien spider creature who is millennia old. Despite this, it inexplicably knows the vows in the modern Church of England wedding service – and makes gags about them. This is clearly Russell T with his pantomime boots on, and it's irritating. Yes, I do realise a Christmas special needs gags, but they need to make internal sense. Otherwise they smack you out of the world of the story. Oh yes they do.

Tomorrow, or next year: Salt

Until then, Bonne Annee x

December 30, 2010

New Year special – writing sins that scupper a story Part 1: Caprica series pilot

Weak story links, lazy plotting, wrong point of view, unsatisfying endings… Although Chez Morris we've taken time off from writing, we've seen some DVDs that have roused me to write posts of protest. So, to keep your critical faculties ticking over until life resumes as normal, I thought I'd share them with you in this five-part mini-series. (And yes, beware spoilers…)

Weak story links, lazy plotting, wrong point of view, unsatisfying endings… Although Chez Morris we've taken time off from writing, we've seen some DVDs that have roused me to write posts of protest. So, to keep your critical faculties ticking over until life resumes as normal, I thought I'd share them with you in this five-part mini-series. (And yes, beware spoilers…)

Today: Caprica – series pilot

Caprica started well enough, with a group of teenagers sneaking away to their secret online world. Then these characters are killed, and the focus switches to the fathers of two of the girls.

Writing sin 1: jarring POV shift.

Not all POV shifts are jarring, but this one is. We spend quite a few scenes with these teenagers, getting to know the world and what matters to them. After they die we need to shift to someone else – but instead of that being someone we are interested in, it's the characters who so far seem to have had the least exciting lives. Although the parents will be trying to find out what their kids were involved in, we were promised the teenagers' experience. For this reason, the generational shift is jarring.

Writing sin 2: character is inexplicably stupid for the sake of the plot. Later, one of the fathers tries to put the avatar of his dead daughter into a military robot. Inexplicably, once he has done this he deletes her from the computer – and this is clearly going to be important. Now, I'm no expert, but I never transfer a computer file anywhere without having a backup – and the only things I make are textfiles. A cybernetic scientist would, we would think, be neurotically careful, especially if the files were consciousness of his dead daughter. But for the sake of making the transfer a once-only thing, he had to do something stupid.

Tomorrow: Doctor Who Christmas special – The Runaway Bride

December 19, 2010

Characters: choose their enemies and friends wisely

The magic happens when your characters are together

Your characters don't exist in a vacuum, but as a complex ensemble. So choose their friends and enemies carefully

There's a game going round on Facebook – write down as fast as possible 15 fictional characters who have influenced you and will always stick with you.

This is the list I rustled up:

1 Cordelia (surname probably Lear)

2 Catherine Earnshaw (Wuthering Heights)

3 Jill Crewe (from Ruby Ferguson's Jill pony books)

4 Doctor Who (Jon Pertwee incarnation)

5 Charles Ryder (Brideshead Revisited)

6 James Bond

7 Lucy Snowe (Villette)

8 Bathsheba Everdene (Far From The Madding Crowd)

9 Eva Khatchadourian (We Need to Talk About Kevin)

10 The narrator of Tanith Lee's Don't Bite The Sun

11 Alexa (from Andrea Newman's eponymous novel)

12 The gay vampire in Fearless Vampire Killers

13 Ray (hitman in In Bruges)

14 Robert Downey Junior's Sherlock Holmes

15 Purdey (The New Avengers)

I thought of the list in a hurry, as per the rules, and as you can see some of them have nothing to tell a serious student of storytelling. But my choices aren't the point of this post. The point is, I found the exercise surprisingly difficult.

Characters in a story are like an ensemble

Only one character?

In each case, I didn't feel it was fair to single out one character – because their memorable, influencing journeys relied on other characters too.

A character makes a lasting impression because of the other characters they spark off.

To look at my list, who is Cordelia without peevish Lear, scheming Goneril and viperous Regan? Who is Eva Khatchadourian without the terrifying Kevin, sweet Celia and straightforward Franklin? Who is Charles Ryder without his dreary father the divine Flytes?

Characters in a story are like a choir. It takes the whole ensemble to bring out what is in the MC and they deserve the credit too.

What about Lizzie Bennett?

Some characters are so iconic that you could argue they deserve the spotlight to themselves. Lizzie Bennett, for instance – where was my head when I left out her? She's good value wherever she goes. But we see that only because her sparring partners are so well chosen. Indeed in that respect, Mr Collins and Lady Catherine de Bourgh are even more delightful than the essential Mr Darcy.

No character operates alone

No character goes through a story alone. Part of the writer's fun is putting characters with others who will bring out the best, worst, be their opposites, nemesis, thwart them, push them to the edge and put their arms around them.

Who makes your main character most interesting? Who makes them do things? Who gets under their skin? Who completes them – or might destroy them?

So let's play this game my way. You've seen who some of my favourite character combinations would be, and why – tell me some of yours.

December 14, 2010

How do you know when your book is finished?

You could edit a book for ever – so how do you know when to stop?

You could edit a book for ever – so how do you know when to stop?

First of all, apologies for this post being so late. We've had massive internet blackout chez Morris and no joy from the online help people. This post is being brought to you from a thin-walled internet cafe under a gurgly bathroom in which a gentleman appears to be having a very productive cough. But, like him, I feel so good to get it out at last.

Anyway, on with the post. I've had a great question from Tara Benwell: How do you know when to stop editing your novel, especially when you hear different advice from different editors and readers?

Novel-writing must be the ultimate artform for editors and perfectionists. Unlike painting, where too much tinkering might turn a strong piece to mush, most books – fiction or non-fiction – only get better with repeated attention.

Indeed, getting a novel right is such a complex job you could edit for ever and some writers would if the writing universe would let them. So how do we tell when it's safe to stop tweaking?

Is it your first?

If it's your first novel, it's particularly hard to know when to stop. Your first novel is the book that teaches you to write. Baby steps turn to giant leaps and by the time you have a polished draft you're eager to see if it's a contender. But many first-time writers query before the manuscript is really ready.

If you have edited until you can't think of anything more to do, and you feel the story is sharp and sparkling, don't send it to an agent or publisher. Give it to a trusted reader. It doesn't have to be an industry professional, but it does have to be someone whose literary judgement you trust and who will give you an honest opinion. Then digest their commentary, be surprised at their insights and your blind spots, dust yourself off and edit again.

Time to stop being solitary

Writing is primarily a solitary activity – at least while we're doing it. But all the writers I know reach a point where they need feedback from their trusted readers. Finishing is something we all have trouble with and no writer I know can do it without help.

Different advice?

Tara's obviously gone through these stages and has discovered a new joy in critical feedback – conflicting suggestions. Make it a thriller, no, make it a romantic suspense. Make chapter seven the prologue; no, get rid of all that material in chapter 7. Put the parrot centre stage; no, get rid of the infernal parrot. There's clearly something wrong in the manuscript, but which advice do you follow?

To make sense of conflicting advice, you have to delve a little deeper into your critics' expectations. What kind of book did they think they were reading? Is it what they usually like to read? Were they comparing it to one that is already on the market? If you know that, you can see why they made their suggestions – and can decide if that is the way you want your book to go.

Conflicting advice from agents and publishers

Sometimes this kind of feedback comes from agents or publishers. As above, this might indicate there is a flaw that needs fixing – in which case, work out which advice fits best with the kind of book you want to write. But wildly conflicting advice might also be an indication that the publisher wants to slot it into a spot in the market that it doesn't yet fit. Your book may be perfectly good as it is, but these days a quality book doesn't automatically earn a deal.

So should you make those changes? It's worth considering if there is a guarantee that they will publish – but there isn't always and you could do all that work for nothing. Should you carry on looking for a home where your book fits better? After all, fashions change. Every case is different and it's a tough call.

Great novels aren't finished, they're pushed out of the nest

I'm going to let you in on a secret. None of us published writers ever think we've finished our novels. Allow any of us to pick up our work again six months after finishing and we'll find things to change, think of better ways to skin the cat or save it. We'll read favourite passages and suck our teeth. Editing is kind of anxiety habit for not doing it all perfectly the first time. We all have a feeling that we could do this novel just a teensy bit better with one more pass.

But at some stage the sand runs out of the hourglass, the imperfections we notice get smaller and smaller, our inner circle of readers are happy and we push it nervously out of the nest.

Finished is a relative term

And then there are degrees of finished. When the manuscript reaches an agent or publishing house, it comes back with queries and notes. Just like your beta readers, your agent or editor will raise questions you'd never dreamed could be asked about your plot, make inferences about your characters that you hadn't a clue were possible – and you'll feel like you're back to square one.

In reality, a book is finished when everybody is reasonably happy.

If you don't have a deadline, how do you know when to stop?

There are people who refine the same book for ever, but maybe they're not doing any good. Perhaps they're polishing so far it's down to the bare metal. Or they're constantly reinventing their style by redoing the same story when they should start a new one.

As writers we're learning and changing all the time. If I'd started my current WIP five years ago I wouldn't do it the way I'm doing it now. We write our books according to the writer we are at the moment. Some tricks and devices I thought were smart five years ago I wouldn't use now. To me they're obvious, although readers may not mind them at all. They only matter to me as I develop my art. I'm not interested in the same themes, problems and types of character as I was half a decade ago. So I do the book as well as I can at the moment, make sure it works on its own terms and for the people who will read it, and move onto a new phase of my writing life.

Is the book finished?

In the end, all we can do is build our trust in the book and let it go.

Thank you, Pinkmoose on Flickr, for the photo.

How do you know when your book is finished? Share in the comments – I may not get to them immediately, but I love a good discussion and I'll reply as quickly as possible

November 28, 2010

Story structure – the secret of compelling storytelling

Structure is how we knit our story together

If I had to pin down the single most important secret of powerful storytelling, it would be structure. Here's why

This week I hosted a forum on the Facebook group Writers Etc and kicked off with this discussion about story structure. Here it is, slightly expanded, buffed and clarified…

Good storytelling is about grabbing the reader, making them care, worrying them, disappointing them, cheering them up, giving them hope, making them bite their nails because they can't bear the suspense, making them miss their train stop and making them stay up until they finished the book. This is partly done with voice and point of view, but mostly with an acute awareness of how to use the events and where to place them – the structure.

Plot is not just events

Events in a novel are rarely superficial. They are a force pulling the characters through the most important experiences of their lives. This principle holds no matter what we are writing, from a fast-paced thriller to a tangled study of a relationship.

I find that more and more, I am sculpting my novels by concentrating on what the structure does.

Once I have my characters and a rough idea of the story, I know the kinds of things they will do and the resources at their disposal. I usually find there are half-a-dozen places a scene could logically go, so I have to find the right one – the one that will answer or ask a question, create a surprise, light a fuse or generate extraordinary tension. A good half of my creative time is spent experimenting with my story's events in different orders to discover where they matter the most.

Courage to experiment

So to structure stories effectively, you need courage to experiment. When I critique manuscripts I find many of my clients can't see their novel's structure. They have a lot of events that don't advance the story, or need to come earlier or later or be reshaped from a different perspective. When I suggest reordering events they don't dare, fearing it's an unmanageable task. Usually, the biggest help I can give them is to show them how to see their novel as a whole and use each story development to its best potential. One of them is my beat sheet tool, which you can see demonstrated here on the opening of the first Harry Potter novel.

Most of us can think of interesting stuff to put in our stories. It's the way we knit it together that matters – who does what, who it changes, what it makes them want to do and whether that makes things better or worse. Get it right, and you won't have any ho-hum sections where the story is spinning its wheels. You'll see where the reader will welcome a good dollop of back story. Everything will flow naturally from the characters' needs, hopes and fears – and when a story works like that, the reader will be drawn along irresistibly.

The beat sheet is one of the tools in Nail Your Novel – Why Writers Abandon Books and How Your Can Draft, Fix and Finish With Confidence. Available from Amazon.com and outside the USA from Lulu.

Thank you, Freya Hartas, for the picture. You can find more of Freya's fabulous art at her blog Carl Has The Funk.

November 21, 2010

Call me Ishmael… When to reveal your MC's name if writing in first person

Daisy Hickman from SunnyRoomStudio has sent this question. 'How soon, when writing in first person, does the story need to reveal the full name of the protagonist? And how do I weave it in? It always feels awkward.'

Daisy Hickman from SunnyRoomStudio has sent this question. 'How soon, when writing in first person, does the story need to reveal the full name of the protagonist? And how do I weave it in? It always feels awkward.'

Slipping in your first-person narrator's name is a small matter but often feels awkward. It's logically unnecessary, since the narrator is talking to the reader directly. Of course, naming shouldn't look like a piece of explanation for its own sake, the dreaded exposition. So writers can tie themselves in knots bringing in other characters who will intrude with a plausible reason to utter their name.

Dickens and du Maurier

Here's how Charles Dickens handles naming in Great Expectations:

My father's family name being Pirrip, and my Christian name Philip, my infant tongue could make of both names nothing longer or more explicit than Pip. So I called myself Pip, and came to be called Pip.

This is the opening paragraph of the entire novel. No messing there. But actually, Dickens has another reason for giving us his MC's name so early. For much of the book Pip isn't very likable, but every time we see the name Pip used later on, we are reminded of his child self.

At the other end of the naming spectrum is Daphne Du Maurier's narrator in Rebecca. She doesn't have a name at all until she marries Max and becomes Mrs de Winter. This is logical because until she marries she is a paid companion, with no status and nothing of her own and no one ever uses her name. It is also resonant– the girl has no identity, to herself or to the rest of society, until she becomes Mrs De Winter. And of course she feels like she is an impostor… I could go on.

Dickens had a good reason for giving us Pip's name at the very start. And Du Maurier had a good one for not giving a name at all. So the reader isn't going to feel lost or annoyed if the protagonist's name isn't revealed for quite some time.

Names in a first-person narrative are usually pretty peripheral anyway, unlike third person, where the name can be a profound symbol. You can get interested in a first-person character without knowing their name. We do it all the time in real life.

A terrible memory for names

How many times do you hear people say they don't have a good memory for names? When we first meet people, we remember them more by what we connected or disagreed over. I have a friend who I first met when she was crazy for a handsome Italian guy she worked with. It was a few weeks before her name was ingrained in my brain, but I remembered every detail of her romantic plight effortlessly – and always will, even though they have married, had a daughter and divorced.

Your first connection with someone who talks to you as 'I' has little to do with a name. (Usually. Except for Pip. And Ishmael in Moby-Dick, who has chosen a symbolic name that tells us something about his character.)

Safety net

Also, to an extent, you have a safety net. Where is the first place a reader looks once they're enticed by your title or cover? The blurb. Most blurbs – or the Amazon version – slip in the protagonist's name anyway. If the reader really starts to feel rudderless, they can look there. (This may seem like a cheat but it's not a bad idea to write with an awareness of what is on the blurb. Lionel Shriver was spurred to find an extra twist in We Need To Talk About Kevin because she knew the flap copy would give away the novel's main event. But I digress.)

Key points

Don't be in a panic to slip the name in. It takes as long as it takes.

If you have a brilliant reason for doing it at the beginning, like Great Expectations and Moby-Dick, then do it. If it doesn't naturally arise until later, don't fret – it's not the most important thing the reader wants to know.

Don't try to shoehorn in a tired scene where the character picks up the morning post and sighs that someone has misspelled their name.

As with all kinds of back story, see if you can use the name-revealing for something else as well.

Thank you, Daisy, for a great question, and Thunderchild7 on Flickr for the picture. Let's share some examples: first-person introductions that work brilliantly – and ones that make you cringe

November 14, 2010

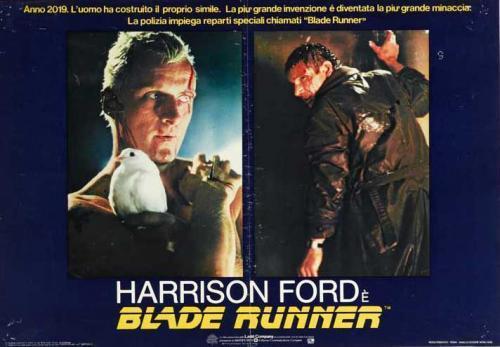

A plot twist too far – was Rick Deckard a replicant?

Have you thought of a brilliant twist for your plot? How does it fare in the Blade Runner test?

Have you thought of a brilliant twist for your plot? How does it fare in the Blade Runner test?

Who doesn't love Blade Runner? It's one of the few films I could watch again and again. But I don't have much time for discussing whether the main character Rick Deckard is a replicant, like the characters he has been sent to kill.

No, actually I do. He isn't a replicant. Period. Because if he is, that weakens the whole story. It's a twist too far. It's the kind of idea that gets invented when you analyse a story to the nth degree and keep looking for more and more.

But it's a lesson for all of us when we're plotting our novels. We constantly wonder if we've got enough twists. We want the reader to think, wow, I didn't see that coming (yet it was there all along). And novels take so long to write that we're in danger of getting bored or losing confidence in our surprises.

When I'm plotting I try out a lot of twists, big reveals and payoffs. Quite a lot of them I throw away because they're not quite right. Rick Deckard being a replicant would be one of those. Yes, it's a twist. It's possibly signposted by clues. It's dripping with irony. But it is wrong. Here's why.

Blade Runner is about a man who has lost his humanity. His job is killing robots. But he's woken up to life again when he falls in love with one of them (Rachael Tyrell). Then the last robot on his hitlist, Roy Batty, saves his life and shows that he has been a more complete, remarkable human than Deckard ever has. If Deckard is human, isn't that perfect, ironic and life changing?

If Deckard is a replicant too, what do we have? A story about a robot who thinks he's human, killing other robots, some of whom have had more exciting lives. Hardly gets the pulse going, does it?

If Deckard is a replicant too, what do we have? A story about a robot who thinks he's human, killing other robots, some of whom have had more exciting lives. Hardly gets the pulse going, does it?

Of course, it is essential that Deckard – and the people he works with – lack humanity. But these are rewarding as themes and ironies. If they turn out to be literally true it robs the idea of much of its power. It also destroys our emotional connection. One of the reasons Blade Runner leaves us with a yearning ache is that we ask, on a smaller scale, how much of our humanity do we lose? How many of us really make the most of life?

Stories work on two levels – the superficial action and the deeper emotional journey. But often when we're trying to squeeze the most out of a plot, we can squeeze too far. If you've thought of a radical twist, don't think only about the literal events of the story. Do the Blade Runner test. Look at the essential emotional arc that is connecting with the reader. Ask if you have twisted too far.

Have you pulled back from a twist too far? Do you have any examples from novels or movies? Share in the comments.

November 8, 2010

How to write fights, games, races and chases – in three easy stages

Action scenes can be tricky to write. Here's

Action scenes can be tricky to write. Here's

a three-step plan to nail them

1. Write first, fix the pace later

'He stepped back to avoid the fist that came at him like a sledgehammer. Then he grabbed the arm and twisted, but his opponent had already recovered his balance and the teapot was whizzing towards him.'

Writing action is slow. Dead slow. When you're plodding through every blow, twist, feint and reaction your exciting scene becomes a dire trudge. But you need to get the details down because those are your raw materials.

I remember in one early thriller I wrote there was a cliff-top chase, which culminated in the MC diving into the sea. It was supposed to be spectacular but dear me, it crawled. In desperation, I took out every other sentence (yes, that's how much I had to cut). Suddenly it had the pace I wanted – the slick, breathless scene I imagined when I put it in the synopsis. Now I could see what speed the choreography should be, I checked the details, swapped some in and out – and it worked.

2 You don't have to show absolutely everything

You don't have to show the scene blow by blow. You can give a sense of what the scene feels like without showing every step, every blow, every thrust and counter-thrust. As with every kind of description, telling details that give the emotional feel of the scene are the most important. For instance, this excerpt from Ian Fleming's Goldfinger:

'Ten yards away, Oddjob hardly paused in his rush. One hand whipped off his ridiculous, deadly hat, a glance to take aim and the black steel half-moon sang through the air. Its edge caught the girl exactly on the nape of the neck.'

3 Make it more interesting than just a fight or a chase

Prose is an internal medium, and is much better for internal, or emotional, action. A scene that is just a set of physical instructions is never going to be as interesting as one with significant character interaction, or humour, or a development that matters to someone on an emotional level.

Screenwriter Jane Espenson said she always found it hard to write the fight scenes in Buffy The Vampire Slayer. So she would design the scene about something else – an argument or a revelation between the characters. When that was established, she slipped the fight in around that.

Thank you, Simon Wicks on Flickr, for the photo

Do you find action scenes easy to write or hard? Do you have any tips? Share in the comments!