Roz Morris's Blog, page 109

July 23, 2011

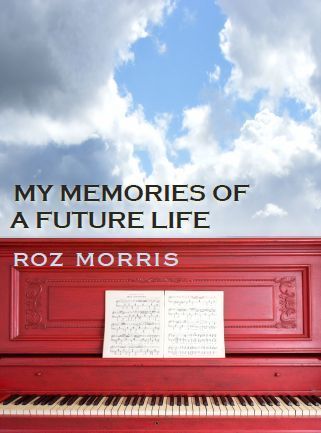

It's a cover! My Memories Of A Future Life – and how to find your novel's theme

A crucial part of introducing your novel to agents or directly to readers is identifying your novel's central theme. But that can be mighty hard to do. Here's how I did it

Final tweaks are being twaught. Kindle hell beckons. Blurb hell too. But cover hell is over, at least the front.

And what theme is this pretty book scratching away at, you may ask? What questions are burning out of the red piano and the blue sky?

Answering that has caused me considerable grief. The journey in the book takes 100,000 words. How do I find one sentence – just one – that captures the heart of it?

It took me a while. Much pacing up and down.

My first thought was, it feels like it's about the whole of life itself. Everything. The universe.

As a theme, 'everything' was a bit, well, vague. And it's the very least you'd expect of a self-respecting well-rounded novel.

Then I made lists of common themes in fiction, as if I was doing an essay for A-level English. It was no help at all.

Everything seemed to fit. Love, loss, friendship, fate. Cheating, lying, haunting, being haunted. Nature, confinement, superstition, the weather. It was easier to find themes that weren't in the book than themes that were.

I had to pull away from 'subjects', because every multi-layered novel will have plenty of them. So I asked myself: what are people doing in this book that gives it its distinctive flavour?

It had to come down to the MC. Her relationships. Her central problem. The patterns that repeat again and again with everyone she meets. The things she reacts to that show what she's searching for. Her peculiar situation and what she needs to understand.

After quarrying down that seam, I had it. This is what My Memories of a Future Life is about.

How do you find where you belong?

You can follow My Memories of a Future Life on Twitter – @ByRozMorris. Not only did the story take 100k words to unroll, its title busts the Twitter name limit

Have you found your novel's theme yet? If so, how did you do it? And if you have, share it in the comments

July 20, 2011

Nearly finished? Make yourself a critical list

Sorry I've been quieter here than usual. Those of you who also follow me on Twitter or have seen my stream in the sidebar will probably know that I'm bolted into my study in the final throes of My Memories of a Future Life. (Can't tell you much about it yet, but it has its own Twitter ID.) So my blog has forgotten it has an owner, Dave has forgotten he's got a wife… or he thinks I've forgotten him. The upshot is that I can't talk sensibly about anything that isn't happening to my characters in their time of crisis.

Sorry I've been quieter here than usual. Those of you who also follow me on Twitter or have seen my stream in the sidebar will probably know that I'm bolted into my study in the final throes of My Memories of a Future Life. (Can't tell you much about it yet, but it has its own Twitter ID.) So my blog has forgotten it has an owner, Dave has forgotten he's got a wife… or he thinks I've forgotten him. The upshot is that I can't talk sensibly about anything that isn't happening to my characters in their time of crisis.

Anyway, while I do these most final of final edits, I invented a little tool that I thought you might find useful if you're also at the last pass. I'm calling it the critical list.

What I'm doing at this stage is test-driving the whole book to see it works as it's supposed to. Speed is of the essence. When we edit we read slowly which is great for detail but gives us a distorted idea of the pace. When we read at the speed a reader does, we understand the flow.

I'm finding points that need a tweak, but that can bog me down to that detail-obsessive snail pace again, which I don't want. So I make a change, whip out a sentence here or reword something there, and keep a note of the page number so that I can come back and check it at editing speed later. Then I go on through the manuscript, running it at the speed a normal reader would.

Big deal, huh? Sorry. This is probably the least profound post I have ever written on the storytelling art. You are probably wondering if I've lost my senses, but such has my world shrunk while in the grip of this book. You're very welcome to share your most trivial writing tip ever in the comments, and I'll be delighted you said hi.

Thank you, Christina Welsh, for the picture – and back soon.

July 10, 2011

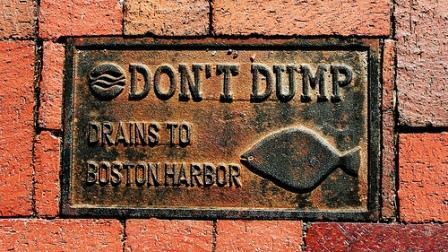

Theme: don't get down in the dumps

Theme is a crucial element of well-rounded fiction, but conveying it can be mighty awkward

Theme is a crucial element of well-rounded fiction, but conveying it can be mighty awkward

Writing is full of potential 'dump' areas. The back story dump, which I talked about last week. The info-dump, aka exposition. And this week, I came across a novel that was wearing its themes rather dumpishly.

When this author wanted to alert us to one of her themes, the characters had a chat about it. Or it was on a TV programme they were watching. Or in the college lecture they'd gone to. So far in this book we've had the failure of language 101, the women's movement 101 and male/female stereotypes 101. (And this isn't, by the way, one of my clients' WIP manuscripts. It's a published literary novel.)

There's nothing wrong with the odd mention of a theme here or there, of course. After all, characters have got to talk about/watch/learn/be interested in something. A line or two won't hurt, to give flavour here and there. So long as you don't stop the action for half a page while you deliver a lecture. (And some writers do it for far longer.)

Bring theme to life

If you feel the need to shake your resonances, you have to do a bit more than dump an essay on the reader. Theme shouldn't come from what the characters intellectually talk about, but from what they feel. The kind of problems that cause trouble for them. Or the way everyone in the universe of the novel behaves. Then the themes become tangible influences in the novel.

So how do you create this feeling?

Sub-plots, my friends

One of the best ways is with sub-plots. Your main plot may examine the theme from one angle; if your sub-plot comes at it another way, that makes the reader more aware of it as a force in the world of your story.

Shakespeare, as we might expect, knew how to make a theme sing for its supper. Take King Lear. In the main plot the king is abdicating and splitting up his kingdom, and trusts the wrong children while wronging the one who is truly decent. In the sub-plot, an illegitimate son (treated badly by everyone from the day he was born) schemes to get his brother disinherited because he feels he deserves his chance. Yes, from time to time the characters deliver speeches about thankless children and unnatural behaviour, but they are provoked by what is what is happening to them. (You can find out more about using sub-plots in my book, Nail Your Novel.)

Themes tend to be intellectual concepts. To make them work in a novel, you have to bring them to life. Not dump them in and constipate your story. I dare you to tweet that line.

Thanks for the picture, Marco/Zak on Flickr

How are you bringing themes alive in your novel? Share in the comments!

July 3, 2011

How to wield back story with panache

How soon can you tell readers your characters' backgrounds? Most writers are in too much of a hurry. Here's how to deploy back story with confidence

How soon can you tell readers your characters' backgrounds? Most writers are in too much of a hurry. Here's how to deploy back story with confidence

We've got a tonne of stuff to let readers know at the start of a novel. What's going on, who wants what, why it matters. And then there's the background to the characters' lives – how they know the people they're with, what they do day to day. All the inventory that isn't action but gives context and depth.

That's back story.

Here are the two main problems with back story.

Most writers fling it in too early.

Most writers dump back story in one big chunk.

Both these problems mean the story grinds to a standstill. Which means the reader stops being engaged.

So how do you judge when is the right time?

First woo your reader

Imagine you have a new acquaintance. I'm talking about real life, by the way. Don't even think of telling them about your life until they're curious about you. Tell them the bare minimum until you've bonded with them in an experience that has drawn you closer together. Even then, give dribs and drabs; don't whammy them with your entire biography. Give only what's immediately relevant, what arises naturally from what you do together and what you already know.

In our hypothetical friendship, can you see how much is being held back? And how the full picture might not come out for a long time?

This is like your book's relationship with the reader.

Your reader meets the book, is pulled into the world of the characters. You have to judge when they are genuinely curious for a dollop of back story. And it's usually much later than you think.

So where do you put it?

I'm just thrashing through a final edit of My Memories of a Future Life, and with a title like that you can bet it's got heaps of back story. Here's what I did.

Cut it all out

I made a copy of the book up to the first turning point and cut out all the back story. It ran very smoothly without its weight of explanation, and offered me natural places to reintroduce a paragraph or two. Once I'd got the characters safely (or perilously) to their point of no return, the reader was warmed up enough to welcome the first chunk of back story.

Here's how I'm dealing with the rest.

Make the back story part of the action

What you imagined as background may not have to stay as background. Could you make it part of the active story? In Life Form 3, which my agent sent out to publishers this week, I caught myself struggling with a lot of explanations. I realised I'd brought the reader in too late. So I started the story earlier and dramatised a lot of the explanations in real time.

Leave it as late as possible

As we said above, there are points in the story where the reader will welcome a few pages about the distant details of the character's childhood, or how they first got a job at the circus. The later you leave it, the more delicious it might be.

Use back story as bonding material

As well as explaining back story directly through the narrator's voice, you can also use it to deepen a bond between two characters in a story. If one character tells another how their relationship with their stepson went wrong, that's miles better than leaving it in back story.

So much of what works in writing mirrors real life. If you think of your book as developing a relationship with the reader, it's much easier to see you can't pitch a chunk of back story in the first few chapters. So woo them a little. Intrigue them. Bond the reader to your characters and to you as a storyteller. There will come a point where your back story is very important to them.

Breaking news – historical and speculative author KM Weiland has obviously been wrestling with this topic recently too. She's just posted a case study on back story in one of Hemingway's classic shorts – check it out here.

Thanks, Binder.donedat for the pic How do you deal with back story? Do you find it a problem? Do share any examples of novels that have handled this well!

June 29, 2011

How to break into ghostwriting

Today I'm guesting about ghosting. Ollin Morales has invited me to his blog Courage2Create, which this year was voted one of Write To Done's Top 10 Blogs For Writers.

Today I'm guesting about ghosting. Ollin Morales has invited me to his blog Courage2Create, which this year was voted one of Write To Done's Top 10 Blogs For Writers.

On Courage2Create, Ollin is documenting his journey to write his first novel and equip himself for a long-term and lasting writing career. As part of that quest, he seeks advice from a diversity of sources, practical to spiritual.

Though I have to confess that despite the name, the ghosting I discuss is entirely practical…

June 26, 2011

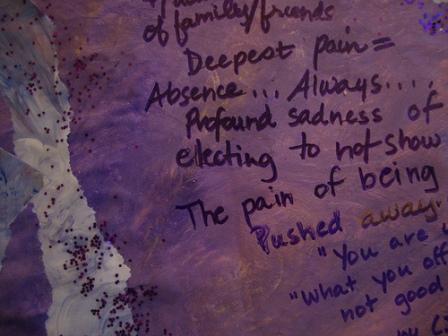

Purple reigns

You may have noticed we're looking more purple here than we used to. I decided the interior and cover of the paperback Nail Your Novel were showing their age and so they've had a complete facelift and I'm switching publisher from Lulu to CreateSpace.

You may have noticed we're looking more purple here than we used to. I decided the interior and cover of the paperback Nail Your Novel were showing their age and so they've had a complete facelift and I'm switching publisher from Lulu to CreateSpace.

The text is exactly the same, but typefaces are clearer and the design simplified. The Kindle edition is already wearing the new cover, as I couldn't wait to put it in its new outfit.

You may also have noticed a certain schizophrenia about the Nail Your Novel covers in the sidebar. Purple on the main Amazon link, blue and coffee on the Bookbuzzr widget. Relax, they are all the same book and the print version isn't vanishing. I'm waiting for my final proof copy to arrive so I can offer the new edition on Amazon, and at that point I'll update the Bookbuzzr widget so it shows the new design. Until then it has to show the book that you'll actually get if you click Buy… clear?

Using CreateSpace should mean the paperback version will be more easily available worldwide. For some reason Lulu didn't like to ship to Amazon buyers outside the US. And those of you who've kicked around here for a while will know that they seriously blotted their copybook when they deleted my Amazon listing early this year, along with my reviews, and then made the book unavailable a second time with no explanation. (Thank you to all of you who repasted reviews when I finally got my listing up again.)

I'll keep the old coffee-n-blue design ticking over on Lulu as the links are scattered far and wide in the blogoverse. I can't update it to the new one for reasons too stodgy to bother you with, but I'll try to let people know in the listing there's also a fresherversion.

But if you've got one of the old blue copies, hang on to it. I just noticed this week that someone's selling them on Amazon Marketplace for USD$136

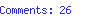

Don't keep your distance – capture the experience

Describing physical or emotional feelings can be a minefield and writers can easily become abstract, which distances the reader. Don't be afraid of finding a simile or metaphor

Describing physical or emotional feelings can be a minefield and writers can easily become abstract, which distances the reader. Don't be afraid of finding a simile or metaphor

The main character in my forthcoming novel* has an ailment of mysterious origin that causes her pain in her hands. So I have my work cut out to find vivid ways to describe it and keep it in the reader's mind.

First problem is variety. So I deployed all the interesting adjectives. Throbbing, pulsing, lancing, searing, burning, nagging, agonising… Nouns too: stab, spasm, twist… you get the picture.

But I'm not there yet. Those synonyms flex the lexical apparatus but they don't let the reader in. They are abstract. They don't make the experience real. They're telling, not showing.

My favourite quote this week from all the posts I've shared on Twitter is this, by Alain de Botton – 'Writing is about capturing experience' .

That's what I needed to do. Bring alive the experience, not plunder the thesaurus.

for similes

for similes

Early on in a key passage I slung in a simile.

'In medieval times there was a kind of torture where your hands were bound in soaking cloths. As they dried they squeezed your hands like little birds in a vice, an inescapable ache hammering in the bones. If I carried an umbrella for half an hour, that's how it would feel.'

A metaphor did the trick in another early passage:

Sometimes I woke in bed at night, imprisoned between long gloves stroked by lightning.

Of course the poor lamb has some nasty medical tests. All praise the simile again:

'When the switch was thrown, an electric current fired down the main nerves and the doctor watched my thumbs twitch. It was painful and peculiar in a sickening way, like grabbing an electric cable and not being able to let go. Not the million volts they use to fry murderers in Alabama, of course. This was a spider-leg scratching, an electrical rasp, a dance of millipedes under the skin that you felt could do bad things to your heart but only if given the long leisure of a professional torturer.'

A few other details to show how the pain limits the character's life (which the umbrella example gets a second tick for), and I was all set. For most of the time, when I needed to remind the reader, my supple synonyms could be offered with confidence.

Telling, showing, aargh

Most writers I know wage a constant battle between telling and showing. We know the character's pain is agonising, so our first recourse is to say that, or find a synonym. But that can be too abstract and distancing. Although similes and metaphors can be overused, like any figure of speech, they can be just what you need to bring an experience alive.

Handle with care

But similes and metaphors have to be chosen with care. The wrong one can be academic and distancing. You always have to ask yourself: how does the experience feel and how would somebody who had it tell me about it?

Here's an example. A friend who lives in Australia was telling me she found an enormous spider. She didn't say 'It was as big as a plate', although that would be accurate. She said: 'hold out your hand, it was that big'.

Sometimes a simple description will do.

That's what we do as writers. We try to capture the experience.

Thank you for the picture, Juliejordanscott on Flickr. Do you have trouble showing instead of telling? In what kind of scenes? Share in the comments!

*My Memories of a Future Life will be available from the end of July

June 19, 2011

Why writers give the best parties

Party scenes are a gift for a writer – here's my celebration

Party scenes are a gift for a writer – here's my celebration

I love a good party. Anyone might collide and anything might start. Or finish. A party is fate's way of throwing a die.

Which makes them perfect for a story.

For some reason, a dinner party scene doesn't do it for me. Of course it can throw folks together, as randomly as you please. But a dinner party is more difficult to choreograph, as most of the action takes place around one table, and juggling a sixsome or eightsome is tricky on the page. Most of the time I find excuses to split them up, sending them out to the kitchen to flatten the soufflé, or outside to have a smoke.

A party, though, comes alive on the page more naturally. Its loose informality means you can drift through a succession of intimate groups or pull back for a long shot. You can use montage to clip a conversation of everything but the most startling line. Or show that somebody is a crashing bore without boring the reader. You can shuffle strangers around with very little contrivance.

What parties can do in a story

Parties might be a focal point for society, as in Jane Austen's novels, when they are often the only times that characters might meet.

Jilly Cooper has rounded off a good number of novels with a rousing gathering, letting the characters bash out their differences under the special conditions a party allows.

A party can also kick off a novel rather well. Iain Banks used a party early in The Crow Road to give a sense of reunion among his characters – and ended the sequence on a poignant note as the MC saw the girl he loved with another guy. Writing as his M alter ego, he used a party early on in one of his Culture books to set up his world.

You might start with a celebration and have it end in tragedy or outrage – as in Sleeping Beauty. The contrast will make the tragedy all the stronger.

Most of the plot of Kingsley Amis's Lucky Jim comes from a party the MC is forced to attend at his new boss's house. The scrapes he gets into set the rest of the book in motion.

A party can have an internalising function too. I used a party scene in My Memories of a Future Life to show the character trying to keep up with her old world after a personal disaster, pretending everything was all right. We can see it isn't. Later in the book, she goes to another party, held by the friends of a character she hopes to find out more about. The surreal atmosphere reflects her internal state as her life takes another swerve. (Two parties may seem heavy going for one book but I atoned in Life Form 3 where there were no parties at all.)

My rules for a good party

So we've established that parties can give you hours of story fun. But like the real thing, they take a bit of organisation. Here are my rules for making your party go with a swing:

1 A party sequence needs a point of view. It could be one POV character or an omniscient camera, but keep it consistent. Don't start as one and end as another.

2 When lingering on groups of people, keep to small numbers. It's extremely hard for the reader to keep track of more than three people foregrounded at a time, and some writers never have more than two. Although you may like that ensemble scene at the start of Quentin Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs, where all the characters are nattering in a café, it does not translate well to the page.

3 Keep letting the camera look up to take in what others are doing and to demonstrate that there are more people there besides the ones you're looking at.

4 If you have a tense exchange, don't hurry away from it too fast because you need to get round to the other people too. Lock the characters in the bathroom together if necessary so that they can take their time.

Thank you, Oddsock, for the picture. And in other news, My Memories of a Future Life will be available on Kindle soon, so that will be an excuse for a party too…

How have you used parties in your fiction? What purpose did they serve in the story? Which writers give the best parties? Share your examples in the comments!

June 12, 2011

Stories are like sharks – to stay alive they must keep moving

A simple trick for writing a compelling story

A simple trick for writing a compelling story

One day I want to write a story that runs backwards. I'll start with the protagonists in a mire of disaster, and then tick back through time, unpicking their mistakes, until they are blithe and bonny.

So I devour all I can about backwards narratives, and the other day I was listening to the actress Kristen Scott Thomas interviewed about her part in Harold Pinter's play Betrayal. The play is a love triangle; husband, wife and wife's lover. The first scene takes place after the affair has ended and the final scene ends when the affair begins.

Aside from indulging my long-range planning, her comments about playing the part clarified something fundamental that writers do when we create any story – backwards or forwards.

Scott Thomas said that Betrayal's chronology stripped away the tools the actors normally used to carry them through a performance. Usually, the actor plugs in at scene one, and what they experience there carries them, changed, into the next one. This domino taps that domino. In each scene their character learns something, commits to something, discards something, and that sets them up for the next. Changing all the time.

This relentless momentum, the decisions and acts that cannot be undone, the words that cannot be unsaid, are the pulse that gives a story its life. It's like a shark who must keep moving otherwise it will die.

That change in every scene is what the actor looks for. It might be gigantic or it might be just a grain. And it is what the writer must look for too.

Thank you, Mrpbps, for the picture. Does each of your scenes have that momentum of forwards change? Do you think there are any situations where a scene can coast without anything changing? Let's discuss!

June 10, 2011

Self-publish first book, seek an agent for the second? Good, bad, risky?

As publishing becomes increasingly like the music industry, should you self-pub to kick-start your career?

As publishing becomes increasingly like the music industry, should you self-pub to kick-start your career?

I've had an interesting question from Stacy Green. 'An online writing friend is going to self-publish a novel to build an audience, and then submit a second book to agents. What do you think'

The writing industry has become like the music industry. Writers are starting their careers not by genuflecting at the desk of an agent or a publisher, but by getting out on blogs and websites, gathering like-minded folks on Twitter and Facebook. Effectively we're gigging.

With Kindle books so cheap and so instantly available, it makes sense to have a book to prove ourselves with as well.

But should you self-publish a novel while you're building your audience?

Is it spoiling your chances of a proper deal?

Six months ago I'd have said it was. But a few trailblazers have changed the world. Crucially, they have proved to the sceptics that self-publishing isn't for slushpile losers. Traditionally published authors who retained their e-rights are putting their backlists on Kindle, showing that 'proper' authors self-publish too. Some agents are thinking of doing it for them. Some authors are ditching their publishers and going it alone, or bringing out their more off-piste work themselves. And there's that Kindle millionaire Ms Hocking. Yes, she's in a minority but a lot of people took notice.

If you self-publish a novel, is it written off?

Agents warn that if you self-publish a book you won't get a deal on it, ever. However, a few self-published authors have had offers for foreign rights. Again, they are in the minority, but it does happen.

For the vast majority, though, no publisher will touch the novel that's been self-published.

That might not matter. Traditional publishing deals hardly pay very much these days so your earnings might not be much different if you keep all the rights for yourself. If you secure a deal for your second book, that will expose you to a wider spread of readers. If they like you, they will probably seek out your first book and won't care where it came from. And so your first novel will not be sacrificed into a void.

But why shouldn't Stacy's friend approach traditional publishers?

Last night I was talking to a former agent and publisher who told me about the soul-destroying business of acquisitions meetings. He and his fellow editors would be passionately championing a book but just one veto from the marketing department could reject it.

The major publishers, he said, will only take potential best-sellers. Market is what speaks to publishers now, even more than merit.

Of course, new smaller publishers are stepping in to take their place, but they only publish a handful of titles a year. You might wait for ever. All the more reason to get out and gig your book.

Before you do…

Here comes the nagging. As everyone says ad nauseum (including me), make sure your book does you credit. Don't toss a novel off so you've got something to get started with. Don't put a book out because you don't dare query with it, or you suspect an editor would tell you there were flaws. Edit and polish as slowly and carefully as you would for a formal query. Get a professional opinion and treat it like a job.

Authors who have blazed a trail this year have demonstrated that self-published writers are capable of policing themselves. Because of this we all have a better chance than ever before of building a career this way. But only if we all set our standards high.

Thank you, Hoong Wei Long for the photo.

To Stacy's friend I say: good plan. If you have a book ready to gig, go for it.

What would you say?