Mary Quattlebaum's Blog, page 8

April 10, 2017

Poetry Power: Poetic Language in Signs

Guest Post by Janet Wong

More people than ever are expressing themselves with art supplies. During the week before the Inauguration and Women’s March(es), people spent $6 million on poster boards and paint markers. While some signs were overtly political, many signs were simple affirmations of our humanity.

With a few Google searches (“protest signs,” “protest art,” “kids protest,” etc.) I found over a thousand examples of inspiring and appealing signs. Many of the most effective signs use poetic devices such as rhyme, repetition, rhythm, alliteration, and wordplay to help them stand out from the crowd—and present learning opportunities for writers. Consider the following examples:

Rhyme: This rhyming text is so much more powerful than, say, “No hatred where I live.”

Repetition: She could’ve said, “No ban, wall, or division.” Would that have been as effective? No, no, no.

Alliteration: “Eighty-nine, feisty, and determined” just doesn’t pack the same punch.

Rhyme, Repetition, and Rhythm: This sign benefits from all three devices: rhyme, repetition, and rhythm.

[image error]

And look at these clever examples of wordplay:

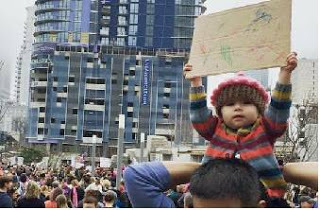

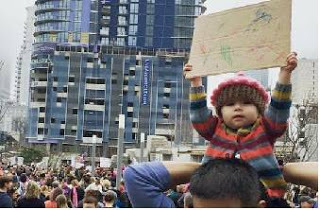

With dozens of favorite signs, it was hard to choose a favorite—but the best sign of all, to me, was probably this one, completely universal in its message and held high:

Which brings me to the point of this piece. Let’s empower kids to make signs.

Look at the pride on these kids’ faces!

Look at the pride on these kids’ faces!

Parents can help kids make signs at home, as language arts exercises.

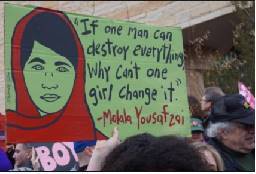

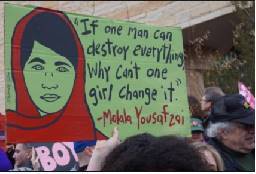

This sign even satisfies a Common Core requirement to teach students about the use of quotes.

This sign even satisfies a Common Core requirement to teach students about the use of quotes.

I am not a particularly “political” person, but I am making a greater effort to inform myself, to engage, and to volunteer for all sorts of activities in an attempt to make a daily difference. To inspire you to get involved in whatever inspires you, here is a prewriting exercise and the title poem from my latest book with Sylvia Vardell, Here We Go: A Poetry Friday Power Book. I hope that you are inspired by this piece to do something like starting a walkathon at your school—and, if you do, make sure to bring sign-making supplies for everyone!

[image error]

[image error]

BIO: Janet Wong (janetwong.com) is the author of 30 books for children and teens, and the co-creator (with Sylvia Vardell) of The Poetry Friday Anthology series and Poetry Friday Power Book series. (PomeloBooks.com).

More people than ever are expressing themselves with art supplies. During the week before the Inauguration and Women’s March(es), people spent $6 million on poster boards and paint markers. While some signs were overtly political, many signs were simple affirmations of our humanity.

With a few Google searches (“protest signs,” “protest art,” “kids protest,” etc.) I found over a thousand examples of inspiring and appealing signs. Many of the most effective signs use poetic devices such as rhyme, repetition, rhythm, alliteration, and wordplay to help them stand out from the crowd—and present learning opportunities for writers. Consider the following examples:

Rhyme: This rhyming text is so much more powerful than, say, “No hatred where I live.”

Repetition: She could’ve said, “No ban, wall, or division.” Would that have been as effective? No, no, no.

Alliteration: “Eighty-nine, feisty, and determined” just doesn’t pack the same punch.

Rhyme, Repetition, and Rhythm: This sign benefits from all three devices: rhyme, repetition, and rhythm.

[image error]

And look at these clever examples of wordplay:

With dozens of favorite signs, it was hard to choose a favorite—but the best sign of all, to me, was probably this one, completely universal in its message and held high:

Which brings me to the point of this piece. Let’s empower kids to make signs.

Look at the pride on these kids’ faces!

Look at the pride on these kids’ faces!Parents can help kids make signs at home, as language arts exercises.

This sign even satisfies a Common Core requirement to teach students about the use of quotes.

This sign even satisfies a Common Core requirement to teach students about the use of quotes. I am not a particularly “political” person, but I am making a greater effort to inform myself, to engage, and to volunteer for all sorts of activities in an attempt to make a daily difference. To inspire you to get involved in whatever inspires you, here is a prewriting exercise and the title poem from my latest book with Sylvia Vardell, Here We Go: A Poetry Friday Power Book. I hope that you are inspired by this piece to do something like starting a walkathon at your school—and, if you do, make sure to bring sign-making supplies for everyone!

[image error]

[image error]

BIO: Janet Wong (janetwong.com) is the author of 30 books for children and teens, and the co-creator (with Sylvia Vardell) of The Poetry Friday Anthology series and Poetry Friday Power Book series. (PomeloBooks.com).

Published on April 10, 2017 14:00

April 3, 2017

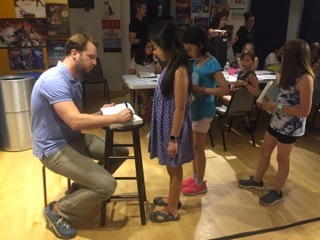

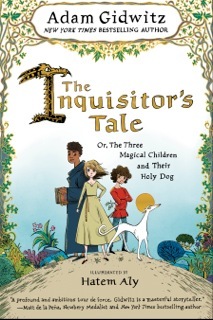

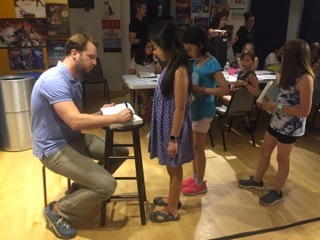

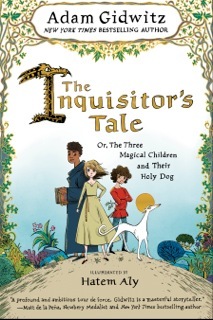

Writing Connections with Adam Gidwitz

by Mary Quattlebaum

Adam Gidwitz’s new novel The Inquisitor’s Taleis proving as popular as his well-known “Grimm” novels, including A Tale Dark and Grimm. In an interview with the KidsPost section of the Washington Post , Gidwitz talks about his research process for this novel, which is set in the Middle Ages. As he traveled in Europe with his wife, a professor of medieval history, Gidwitz read about knights, saints and even a sacred dog. All these things became part of his fictional tale, but he added many of his own intriguing details. For example, the young peasant girl Jeanne is loosely based on St. Joan of Arc, of whom little is known of her childhood. And a farting dragon makes an appearance!

Below are writing lessons for the classroom or for individual writers ages 8 and up. Gidwitz’s website includes a teacher’s guide.

EXPLORING HISTORY: Classroom Discussion: Gidwitz makes the past come alive by centering historic events in the lives of three young people and a dog on a dangerous quest for sacred objects. You might apply his process to the classroom study of any historic time period—or even to the study of current events.

Classroom Writing: Depending on what issue or historical time period you may be studying, you might help kids to connect to it on a more interactive, dramatic level. Have each student make up a character who is involved in a historic event. For example, a girl or boy involved in a suffrage march or Civil Rights Era eat-in. Or a young neighbor helping the Wright brothers to fly the first airplane. Or a youngster trying to grow food in a weedy Victory Garden during WWII. What makes Gidwitz’s novel particularly compelling, though, is that the child characters must deal with uncertainty and danger, which creates suspense. Sinister knights try to kidnap Jeanne; quicksand creates problems for travelers.

Ask students to put their characters in a moment of realistic danger or in the midst of a big problem that they must figure out how to solve/deal with. Have them brainstorm some possible dangers/problems, alone and as a class. What does the main character do? Have students close their eyes and imagine this scene in their heads, focusing on what their kid character might see, hear, smell, taste, and touch as part of this experience. What do their clothes look and feel like? What’s their mode of transportation? Do they have a pet? Are they scared? Angry? Confused?

Students might do some internet or library or classroom book research. For example, looking at historic photographs might give them ideas of details of clothing or historic items to include in their Historic Moments pieces.

Ask students to read their pieces aloud. As a group, discuss what they learned by researching/writing these pieces—and by listening to others’ pieces.

www.maryquattlebaum.com

Adam Gidwitz’s new novel The Inquisitor’s Taleis proving as popular as his well-known “Grimm” novels, including A Tale Dark and Grimm. In an interview with the KidsPost section of the Washington Post , Gidwitz talks about his research process for this novel, which is set in the Middle Ages. As he traveled in Europe with his wife, a professor of medieval history, Gidwitz read about knights, saints and even a sacred dog. All these things became part of his fictional tale, but he added many of his own intriguing details. For example, the young peasant girl Jeanne is loosely based on St. Joan of Arc, of whom little is known of her childhood. And a farting dragon makes an appearance!

Below are writing lessons for the classroom or for individual writers ages 8 and up. Gidwitz’s website includes a teacher’s guide.

EXPLORING HISTORY: Classroom Discussion: Gidwitz makes the past come alive by centering historic events in the lives of three young people and a dog on a dangerous quest for sacred objects. You might apply his process to the classroom study of any historic time period—or even to the study of current events.

Classroom Writing: Depending on what issue or historical time period you may be studying, you might help kids to connect to it on a more interactive, dramatic level. Have each student make up a character who is involved in a historic event. For example, a girl or boy involved in a suffrage march or Civil Rights Era eat-in. Or a young neighbor helping the Wright brothers to fly the first airplane. Or a youngster trying to grow food in a weedy Victory Garden during WWII. What makes Gidwitz’s novel particularly compelling, though, is that the child characters must deal with uncertainty and danger, which creates suspense. Sinister knights try to kidnap Jeanne; quicksand creates problems for travelers.

Ask students to put their characters in a moment of realistic danger or in the midst of a big problem that they must figure out how to solve/deal with. Have them brainstorm some possible dangers/problems, alone and as a class. What does the main character do? Have students close their eyes and imagine this scene in their heads, focusing on what their kid character might see, hear, smell, taste, and touch as part of this experience. What do their clothes look and feel like? What’s their mode of transportation? Do they have a pet? Are they scared? Angry? Confused?

Students might do some internet or library or classroom book research. For example, looking at historic photographs might give them ideas of details of clothing or historic items to include in their Historic Moments pieces.

Ask students to read their pieces aloud. As a group, discuss what they learned by researching/writing these pieces—and by listening to others’ pieces.

www.maryquattlebaum.com

Published on April 03, 2017 14:00

March 27, 2017

“All Talk and No Action”

guest post by Claudia Mills

Oh, that boring word said. We do need to have some way to know which character is speaking in a stretch of dialogue, but to hear said, said, said, said, said, said is almost unbearable.

The only thing worse, alas, is to switch out said for a bunch of “fancy” speech verbs. An occasional shouted, whispered, complained, retorted is a welcome relief, but a long string of hundred-dollar speech verbs calls attention to itself much more than plain old said ever did. Worst of all is modifying each said with an adverb: saidsadly, said angrily, said wistfully.

Solution: introduce brief bits of action into dialogue. Letting us know what characters are doing as they speak not only identifies speakers, but places readers fully in a scene. Instead of talking heads, we have living, breathing, moving human beings.

For example, in my recent book about an aspiring seventh-grade writer, Write This Down, here are some instances where a speaker is identified simply by my showing what she is doing as she speaks:

“That isn’t funny.” Now Kylee’s distressed enough that she puts down her knitting.

Or:

Kylee shrugs. “Okay.” But she crinkles her forehead in a skeptical way.

One way to demonstrate this technique to your students is to create a short dialogue, written as in a play, just the words spoken. Here’s one I use when I teach:

“How are you?” “I’m fine. How about you?” “Just okay.” “What’s the matter?” “It’s my mom.”“What about her?”“I think she’s sick, like really sick.”“Oh, no!”

Have the students name the two characters. Now edit the dialogue (on the board) with each line tagged with, e.g., “John said” or Mary said.” Read it aloud so the students can hear how deadly this is. Next try replacing each said– every single one – with a fancy speech verb, or speech verb plus adverb. Read it aloud. Ouch!

Ah, but now let the students offer suggestions about where the dialogue should take place: in a shopping mall, at the pool, in the school cafeteria? Once a setting has been established, a few of the speech tags can replaced by brief bits of action, specific to that setting. Vary their placement by sometimes having action precede a line of speech and sometimes follow it.

“How are you?” John asked Mary, as they walked toward the pool.“I’m fine,” Mary said. “How about you?”“Just okay.” John fiddled with the towel draped over his shoulders.Mary stared at him. “What’s the matter?” After a long pause, John said, “It’s my mom.”“What about her?” A kid on the high board dove into the water with a huge splash, but Mary didn’t turn to look. “I think she’s sick, like really sick,” John whispered. “Oh, no!”

Don’t let dialogue be “all talk and no action.” Small bits of interspersed action make the talking real. Action makes talkers come alive.

Claudia Mills is the author of over 50 books for young readers, including How Oliver Olson Changed the World (an ALA Notable Book of the Year) and The Trouble with Ants (which received a starred review in Publishers Weekly), as well as the Franklin School Friends series of chapter books from Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Claudia lives in Boulder, Colorado, with her family and her cat, Snickers. Visit her at www.claudiamillsauthor.com.

Claudia Mills is the author of over 50 books for young readers, including How Oliver Olson Changed the World (an ALA Notable Book of the Year) and The Trouble with Ants (which received a starred review in Publishers Weekly), as well as the Franklin School Friends series of chapter books from Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Claudia lives in Boulder, Colorado, with her family and her cat, Snickers. Visit her at www.claudiamillsauthor.com.

Oh, that boring word said. We do need to have some way to know which character is speaking in a stretch of dialogue, but to hear said, said, said, said, said, said is almost unbearable.

The only thing worse, alas, is to switch out said for a bunch of “fancy” speech verbs. An occasional shouted, whispered, complained, retorted is a welcome relief, but a long string of hundred-dollar speech verbs calls attention to itself much more than plain old said ever did. Worst of all is modifying each said with an adverb: saidsadly, said angrily, said wistfully.

Solution: introduce brief bits of action into dialogue. Letting us know what characters are doing as they speak not only identifies speakers, but places readers fully in a scene. Instead of talking heads, we have living, breathing, moving human beings.

For example, in my recent book about an aspiring seventh-grade writer, Write This Down, here are some instances where a speaker is identified simply by my showing what she is doing as she speaks:

“That isn’t funny.” Now Kylee’s distressed enough that she puts down her knitting.

Or:

Kylee shrugs. “Okay.” But she crinkles her forehead in a skeptical way.

One way to demonstrate this technique to your students is to create a short dialogue, written as in a play, just the words spoken. Here’s one I use when I teach:

“How are you?” “I’m fine. How about you?” “Just okay.” “What’s the matter?” “It’s my mom.”“What about her?”“I think she’s sick, like really sick.”“Oh, no!”

Have the students name the two characters. Now edit the dialogue (on the board) with each line tagged with, e.g., “John said” or Mary said.” Read it aloud so the students can hear how deadly this is. Next try replacing each said– every single one – with a fancy speech verb, or speech verb plus adverb. Read it aloud. Ouch!

Ah, but now let the students offer suggestions about where the dialogue should take place: in a shopping mall, at the pool, in the school cafeteria? Once a setting has been established, a few of the speech tags can replaced by brief bits of action, specific to that setting. Vary their placement by sometimes having action precede a line of speech and sometimes follow it.

“How are you?” John asked Mary, as they walked toward the pool.“I’m fine,” Mary said. “How about you?”“Just okay.” John fiddled with the towel draped over his shoulders.Mary stared at him. “What’s the matter?” After a long pause, John said, “It’s my mom.”“What about her?” A kid on the high board dove into the water with a huge splash, but Mary didn’t turn to look. “I think she’s sick, like really sick,” John whispered. “Oh, no!”

Don’t let dialogue be “all talk and no action.” Small bits of interspersed action make the talking real. Action makes talkers come alive.

Claudia Mills is the author of over 50 books for young readers, including How Oliver Olson Changed the World (an ALA Notable Book of the Year) and The Trouble with Ants (which received a starred review in Publishers Weekly), as well as the Franklin School Friends series of chapter books from Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Claudia lives in Boulder, Colorado, with her family and her cat, Snickers. Visit her at www.claudiamillsauthor.com.

Claudia Mills is the author of over 50 books for young readers, including How Oliver Olson Changed the World (an ALA Notable Book of the Year) and The Trouble with Ants (which received a starred review in Publishers Weekly), as well as the Franklin School Friends series of chapter books from Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Claudia lives in Boulder, Colorado, with her family and her cat, Snickers. Visit her at www.claudiamillsauthor.com.

Published on March 27, 2017 14:00

March 20, 2017

Comparison Poem--One Minute Till Bedtime

by Jacqueline Jules

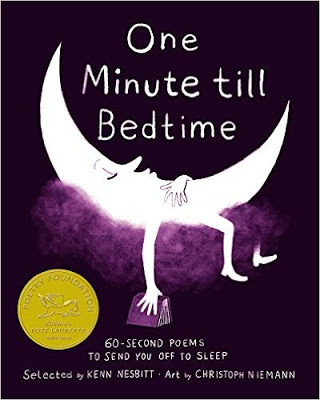

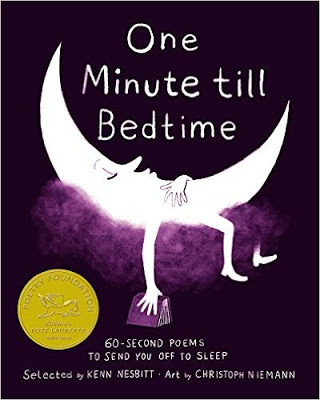

How do you inspire students to write beautiful poetry? Share beautiful poetry in your classroom! A wonderful new resource is One Minute Till Bedtime selected by former Children’s Poet Laureate Kenn Nesbitt. This extensive collection features new poems from Jane Yolen, Jon Scieszka, Nikki Grimes, Jack Prelutsky, Lemony Snicket, Mary Ann Hoberman, Eileen Spinelli, and dozens of other well-known children’s authors. Each poem is a minute in length, perfect for a quick transitional moment before lining up for lunch, dismissal, or specials. It’s also perfect for calming a class down to begin social studies or math. Dreamy illustrations by Christoph Niemann will invite young readers to cuddle up with this book in a corner. If you are looking for poetry to add to your classroom library, this should be on your wish list.

For the writing workshop, One Minute Till Bedtime provides a wide selection of poems on various topics to use as models. You will find poems on virtually any subject of interest to your students. Family relationships, school, home, food—it can all be found in this 164 page compendium of rhyme, rhythm, and figurative language. Particularly notable are poems on the seasons, which could tie in to the science curriculum. Poems on animals also abound. My contribution to this collection is a poem called “Pigeon.”

Illustration by Christoph Niemann

Illustration by Christoph Niemann

from One Minute Till Bedtime

Read this poem to your students and discuss how the poem compares pigeons to other birds. Challenge them to write their own comparison poem. How does a flamingo compare to a penguin? How does a frog compare to a toad? This activity requires some science related research to compare two animals. Integrating language arts with science expands critical thinking skills and creativity!

Happy researching and writing!

www.jacquelinejules.com

How do you inspire students to write beautiful poetry? Share beautiful poetry in your classroom! A wonderful new resource is One Minute Till Bedtime selected by former Children’s Poet Laureate Kenn Nesbitt. This extensive collection features new poems from Jane Yolen, Jon Scieszka, Nikki Grimes, Jack Prelutsky, Lemony Snicket, Mary Ann Hoberman, Eileen Spinelli, and dozens of other well-known children’s authors. Each poem is a minute in length, perfect for a quick transitional moment before lining up for lunch, dismissal, or specials. It’s also perfect for calming a class down to begin social studies or math. Dreamy illustrations by Christoph Niemann will invite young readers to cuddle up with this book in a corner. If you are looking for poetry to add to your classroom library, this should be on your wish list.

For the writing workshop, One Minute Till Bedtime provides a wide selection of poems on various topics to use as models. You will find poems on virtually any subject of interest to your students. Family relationships, school, home, food—it can all be found in this 164 page compendium of rhyme, rhythm, and figurative language. Particularly notable are poems on the seasons, which could tie in to the science curriculum. Poems on animals also abound. My contribution to this collection is a poem called “Pigeon.”

Illustration by Christoph Niemann

Illustration by Christoph Niemannfrom One Minute Till Bedtime

Read this poem to your students and discuss how the poem compares pigeons to other birds. Challenge them to write their own comparison poem. How does a flamingo compare to a penguin? How does a frog compare to a toad? This activity requires some science related research to compare two animals. Integrating language arts with science expands critical thinking skills and creativity!

Happy researching and writing!

www.jacquelinejules.com

Published on March 20, 2017 14:00

March 13, 2017

Encouraging Nonfiction Writing in School

Guest Post by Moira Rose Donohue

When I was a kid, I read fiction with two very limited exceptions: I read books about dogs and ballet. As an adult, it was pretty much the same story. So when I started writing for children, naturally I wrote only fiction. Then, a number of years ago, I was asked to write a series of nonfiction books about civil rights figures in Virginia. Hmmm. I didn’t think there would be a lot of dogs or ballerinas involved. And it sounded a little like homework.

I thought about it for a while. I didn’t mind the research. In fact, I was ready to learn new things. But it was the thought of note taking on small white index cards, one thought and source to a card, made me feel faint. I absolutely hated doing that in school. But fortunately, before I said, “NO,” I had an epiphany: I can take notes in a way that works for me.

I realize that piles of index cards with one or two lines on each one may be a great organizational tool for some. But for me, a visual learner, that stack, with all that wasted space, is totally overwhelming. If I could take notes in my tiny handwriting, on colored legal pads, with page numbers in the margins, I would be much happier. Then I could star things that I liked, use pink highlighter on facts I wanted to be sure to include and annotate others with cross-references. I could even color code things. It worked. In fact, I kept writing nonfiction and I haven’t looked back.

Writing nonfiction teaches the writer so much. So why not encourage your students to write nonfiction?

GETTING STARTED: Before setting children to the task of writing nonfiction, it’s important to have them read nonfiction. Next, pick topics that they can research easily. Writing about animals is a good starting place, because animals, in general, are less mired in conflicting information. Then consider moving into cultural and biographical subjects. I would suggest that you save history, especially long-ago history, for later, as it is hardest area in which to verify facts.

RESEARCH: This is a great time to teach children that not everything they read is true. It’s not about finding three sources that say the same thing anymore, like when I was a kid. And not all internet sites are reliable. Finally, sometimes it’s a question of saying “experts differ.”

NOTETAKING: Obviously it is crucial to keep track of where a particular bit of information comes from. But it doesn’t have to be done on white index cards. I would suggest providing children with several options.

OUTLINING: It’s a good idea to ask students to outline their stories, but only in a general way to give the story some structure. Then comes the really fun part. A writer I really respect told me that when you are researching a topic and come across something that makes you say, “Wow!” include it in your story. If it surprises you, it will surprise others as well. I encourage you to share this idea with your students. And then let them put pencil to paper! BIO: Moira Rose Donohue has written over 20 nonfiction books for children. The Invasion of Normandy from North Star Editions came out in January 2017. Dog on a Bike from National Geographic was released in February 2017. Moira offers a school program called "Writing Interesting Nonfiction" that she loves to present to elementary schools. And she still loves dogs and ballerinas. Visit www.moirarosedonohue.net

BIO: Moira Rose Donohue has written over 20 nonfiction books for children. The Invasion of Normandy from North Star Editions came out in January 2017. Dog on a Bike from National Geographic was released in February 2017. Moira offers a school program called "Writing Interesting Nonfiction" that she loves to present to elementary schools. And she still loves dogs and ballerinas. Visit www.moirarosedonohue.net

When I was a kid, I read fiction with two very limited exceptions: I read books about dogs and ballet. As an adult, it was pretty much the same story. So when I started writing for children, naturally I wrote only fiction. Then, a number of years ago, I was asked to write a series of nonfiction books about civil rights figures in Virginia. Hmmm. I didn’t think there would be a lot of dogs or ballerinas involved. And it sounded a little like homework.

I thought about it for a while. I didn’t mind the research. In fact, I was ready to learn new things. But it was the thought of note taking on small white index cards, one thought and source to a card, made me feel faint. I absolutely hated doing that in school. But fortunately, before I said, “NO,” I had an epiphany: I can take notes in a way that works for me.

I realize that piles of index cards with one or two lines on each one may be a great organizational tool for some. But for me, a visual learner, that stack, with all that wasted space, is totally overwhelming. If I could take notes in my tiny handwriting, on colored legal pads, with page numbers in the margins, I would be much happier. Then I could star things that I liked, use pink highlighter on facts I wanted to be sure to include and annotate others with cross-references. I could even color code things. It worked. In fact, I kept writing nonfiction and I haven’t looked back.

Writing nonfiction teaches the writer so much. So why not encourage your students to write nonfiction?

GETTING STARTED: Before setting children to the task of writing nonfiction, it’s important to have them read nonfiction. Next, pick topics that they can research easily. Writing about animals is a good starting place, because animals, in general, are less mired in conflicting information. Then consider moving into cultural and biographical subjects. I would suggest that you save history, especially long-ago history, for later, as it is hardest area in which to verify facts.

RESEARCH: This is a great time to teach children that not everything they read is true. It’s not about finding three sources that say the same thing anymore, like when I was a kid. And not all internet sites are reliable. Finally, sometimes it’s a question of saying “experts differ.”

NOTETAKING: Obviously it is crucial to keep track of where a particular bit of information comes from. But it doesn’t have to be done on white index cards. I would suggest providing children with several options.

OUTLINING: It’s a good idea to ask students to outline their stories, but only in a general way to give the story some structure. Then comes the really fun part. A writer I really respect told me that when you are researching a topic and come across something that makes you say, “Wow!” include it in your story. If it surprises you, it will surprise others as well. I encourage you to share this idea with your students. And then let them put pencil to paper!

BIO: Moira Rose Donohue has written over 20 nonfiction books for children. The Invasion of Normandy from North Star Editions came out in January 2017. Dog on a Bike from National Geographic was released in February 2017. Moira offers a school program called "Writing Interesting Nonfiction" that she loves to present to elementary schools. And she still loves dogs and ballerinas. Visit www.moirarosedonohue.net

BIO: Moira Rose Donohue has written over 20 nonfiction books for children. The Invasion of Normandy from North Star Editions came out in January 2017. Dog on a Bike from National Geographic was released in February 2017. Moira offers a school program called "Writing Interesting Nonfiction" that she loves to present to elementary schools. And she still loves dogs and ballerinas. Visit www.moirarosedonohue.net

Published on March 13, 2017 14:00

March 6, 2017

Tips, Tricks and a Little Bit O’ Luck!

guest post by Sue Fliess

When I was growing up, making leprechaun traps was simply not a thing. I’m not sure when it became a trend, but I know that my first reaction as a mom of preschoolers was, “Oh, great, I’m already so tired and now I have one more thing I have to do!”

But I must confess: I think I enjoyed making the traps more than my children did! I got so into it. We used an old fish tank, painted some rocks gold, made a ladder, and propped open the fish tank like an animal snare. My boys helped in all of this—as much as 3 and 5 year olds can—and decorated the tank with shamrocks and rainbows.

But it wasn’t enough for me to stop there. I knew my boys would want proof that a leprechaun stopped by. So, I left a note (which rhymed, of course!) from Liam the Leprechaun, which gave my boys clues for looking for the treasures he’d stolen, which I’d placed around the house. We did this for a few years, until they grew out of it—or, more truthfully, my older son grew frustrated with never catching Liam. Once he wrote a note back to Liam expressing just that.

All of this planted the seed for my new book, How To Trap a Leprechaun, long before I knew I would write it. But when I sat down to write it, all of the material presented itself from my own experience. It was one of those books that flew from my brain to the page with relative ease.

This how-to book written in rhyme explains to kids what leprechauns are and what they might be attracted to, so kids can decide how to build their traps, what types of things to put in the traps, and how they might decorate them. There is even some instruction in the back of the book for teachers/educators.

Depending on the age of the kids you’re working with, there are lots of ways to present a how-to writing activity on building a leprechaun trap.

Simple MachinesHave this be a ‘simple machine’ building day. Require kids to have one moving part to their traps. Maybe an incline, pulley, or a lever.

Rubric practice Create a rubric for the trap, making sure they use one or more specific materials, such as, ‘you must use at least one pipe-cleaner, and it must have a shamrock.’

Plan it! Have them create a blueprint before starting. They can draw a picture of what they want the trap to look like, and write out the steps they’ll take to make the trap.

CollaborationPut them in small groups to have it be a collaborative trap-building activity (like the kids in my book). This promotes teamwork and brainstorming.

An unstructured structureYou can also just keep it completely unstructured. Put out materials and/or encourage them to bring some materials from home to use in their traps. Let them create in an unstructured environment.

Whatever assignment you give, you may want to ask the students to do presentations when they are finished. This gives them a public speaking opportunity where they’ll have to clearly explain something in multiple steps: how the leprechaun may be lured, how he might enter the trap, what will keep him there. Every trap is sure to be very different! Emphasize that there’s no wrong way to make a leprechaun trap, so every effort is commended.

BIO: Sue Fliess ("fleece") is the author of numerous children's books including A Fairy Friend, Calling All Cars, Robots, Robots Everywhere!, The Hug Book, Tons of Trucks and Shoes for Me! Her background is in copywriting, PR, and marketing, and her articles have appeared in O the Oprah Magazine, Huffington Post, Writer's Digest, Education.com, and more. Fliess has also written stories for The Walt Disney Company. Her picture books have received honors from the Society of Children's Books Writers and Illustrators, have been used in school curriculums, museum educational programs, and have even been translated into French. She's a member of SCBWI and The Children's Book Guild of DC. Sue lives with her family and a Labrador named Charlie in Northern Virginia. Visit her at http://www.suefliess.com/

BIO: Sue Fliess ("fleece") is the author of numerous children's books including A Fairy Friend, Calling All Cars, Robots, Robots Everywhere!, The Hug Book, Tons of Trucks and Shoes for Me! Her background is in copywriting, PR, and marketing, and her articles have appeared in O the Oprah Magazine, Huffington Post, Writer's Digest, Education.com, and more. Fliess has also written stories for The Walt Disney Company. Her picture books have received honors from the Society of Children's Books Writers and Illustrators, have been used in school curriculums, museum educational programs, and have even been translated into French. She's a member of SCBWI and The Children's Book Guild of DC. Sue lives with her family and a Labrador named Charlie in Northern Virginia. Visit her at http://www.suefliess.com/

When I was growing up, making leprechaun traps was simply not a thing. I’m not sure when it became a trend, but I know that my first reaction as a mom of preschoolers was, “Oh, great, I’m already so tired and now I have one more thing I have to do!”

But I must confess: I think I enjoyed making the traps more than my children did! I got so into it. We used an old fish tank, painted some rocks gold, made a ladder, and propped open the fish tank like an animal snare. My boys helped in all of this—as much as 3 and 5 year olds can—and decorated the tank with shamrocks and rainbows.

But it wasn’t enough for me to stop there. I knew my boys would want proof that a leprechaun stopped by. So, I left a note (which rhymed, of course!) from Liam the Leprechaun, which gave my boys clues for looking for the treasures he’d stolen, which I’d placed around the house. We did this for a few years, until they grew out of it—or, more truthfully, my older son grew frustrated with never catching Liam. Once he wrote a note back to Liam expressing just that.

All of this planted the seed for my new book, How To Trap a Leprechaun, long before I knew I would write it. But when I sat down to write it, all of the material presented itself from my own experience. It was one of those books that flew from my brain to the page with relative ease.

This how-to book written in rhyme explains to kids what leprechauns are and what they might be attracted to, so kids can decide how to build their traps, what types of things to put in the traps, and how they might decorate them. There is even some instruction in the back of the book for teachers/educators.

Depending on the age of the kids you’re working with, there are lots of ways to present a how-to writing activity on building a leprechaun trap.

Simple MachinesHave this be a ‘simple machine’ building day. Require kids to have one moving part to their traps. Maybe an incline, pulley, or a lever.

Rubric practice Create a rubric for the trap, making sure they use one or more specific materials, such as, ‘you must use at least one pipe-cleaner, and it must have a shamrock.’

Plan it! Have them create a blueprint before starting. They can draw a picture of what they want the trap to look like, and write out the steps they’ll take to make the trap.

CollaborationPut them in small groups to have it be a collaborative trap-building activity (like the kids in my book). This promotes teamwork and brainstorming.

An unstructured structureYou can also just keep it completely unstructured. Put out materials and/or encourage them to bring some materials from home to use in their traps. Let them create in an unstructured environment.

Whatever assignment you give, you may want to ask the students to do presentations when they are finished. This gives them a public speaking opportunity where they’ll have to clearly explain something in multiple steps: how the leprechaun may be lured, how he might enter the trap, what will keep him there. Every trap is sure to be very different! Emphasize that there’s no wrong way to make a leprechaun trap, so every effort is commended.

BIO: Sue Fliess ("fleece") is the author of numerous children's books including A Fairy Friend, Calling All Cars, Robots, Robots Everywhere!, The Hug Book, Tons of Trucks and Shoes for Me! Her background is in copywriting, PR, and marketing, and her articles have appeared in O the Oprah Magazine, Huffington Post, Writer's Digest, Education.com, and more. Fliess has also written stories for The Walt Disney Company. Her picture books have received honors from the Society of Children's Books Writers and Illustrators, have been used in school curriculums, museum educational programs, and have even been translated into French. She's a member of SCBWI and The Children's Book Guild of DC. Sue lives with her family and a Labrador named Charlie in Northern Virginia. Visit her at http://www.suefliess.com/

BIO: Sue Fliess ("fleece") is the author of numerous children's books including A Fairy Friend, Calling All Cars, Robots, Robots Everywhere!, The Hug Book, Tons of Trucks and Shoes for Me! Her background is in copywriting, PR, and marketing, and her articles have appeared in O the Oprah Magazine, Huffington Post, Writer's Digest, Education.com, and more. Fliess has also written stories for The Walt Disney Company. Her picture books have received honors from the Society of Children's Books Writers and Illustrators, have been used in school curriculums, museum educational programs, and have even been translated into French. She's a member of SCBWI and The Children's Book Guild of DC. Sue lives with her family and a Labrador named Charlie in Northern Virginia. Visit her at http://www.suefliess.com/

Published on March 06, 2017 14:00

February 27, 2017

“Sure to Spark Intense Discussion”

by Karen Leggett Abouraya

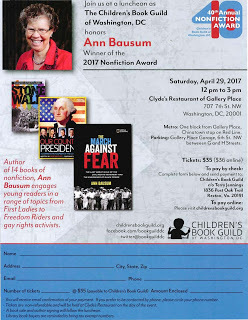

When Ann Bausum wrote Denied Detained Deported: Stories from the Dark Side of American Immigration in 2009, the starred review in Booklistcalled it a “landmark title, sure to spark intense discussion.” Indeed. Eight years later, the discussion might be even more intense.

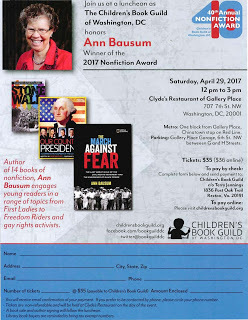

Ann Bausum is the winner of the 2017 Children’s Book Guild Nonfiction Award, given to an author or author-illustrator whose total work has contributed significantly to the quality of nonfiction for children. Bausum’s work is wide-ranging – The March Against Fear: The Last Great Walk of the Civil Rights Movement and the Emergence of Black Power; Stonewall: Breaking Out in the Fight for Gay Rights; Stubby the War Dog and Denied Detained Deported.

In Denied Detained Deported, Bausum ends many chapters with questions that are excellent, thought-provoking writing prompts for teens and in a few cases, younger students.

· “What individual rights should be sacrificed in the name of homeland security?”· “Do migrant workers contribute more to society than they take away?” · “What protections might Americans be asked to forfeit when their heritage makes them suspect during a time of war?”

Whether students are asked to write essays or debate both sides of each question, they can gain experience in using logical reasoning and facts for civil debate and discourse.

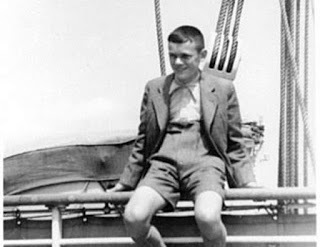

A less intense writing activity would ask students to write a single diary entry for one of the children whose stories are told in the book. What was a day like for Mary Matsuda in a Japanese internment camp or Herb Karliner, a German Jewish boy expecting to sail to freedom and safety in the United States?

Herb Karliner, a German Jewish boy expecting to sail to freedom and safety

Herb Karliner, a German Jewish boy expecting to sail to freedom and safety

in the United States in 1939

There are more stories about Chinese who came seeking gold in California in 1849 and cycles of Mexican migration in the 20th century. As Bausum concludes, “The United States has been alternatively welcoming and hostile to those who have tried to cross through ‘the golden door’ into America.”

While you are contemplating which of Ann Bausum’s books to share with your students, make plans to hear her in person at the Children’s Book Guild Nonfiction Award Celebration on April 29 at Clyde’s Gallery Place in Washington, D.C. Register here . Everyone is welcome!

http://childrensbookguild.org/karen-leggett-abouraya

When Ann Bausum wrote Denied Detained Deported: Stories from the Dark Side of American Immigration in 2009, the starred review in Booklistcalled it a “landmark title, sure to spark intense discussion.” Indeed. Eight years later, the discussion might be even more intense.

Ann Bausum is the winner of the 2017 Children’s Book Guild Nonfiction Award, given to an author or author-illustrator whose total work has contributed significantly to the quality of nonfiction for children. Bausum’s work is wide-ranging – The March Against Fear: The Last Great Walk of the Civil Rights Movement and the Emergence of Black Power; Stonewall: Breaking Out in the Fight for Gay Rights; Stubby the War Dog and Denied Detained Deported.

In Denied Detained Deported, Bausum ends many chapters with questions that are excellent, thought-provoking writing prompts for teens and in a few cases, younger students.

· “What individual rights should be sacrificed in the name of homeland security?”· “Do migrant workers contribute more to society than they take away?” · “What protections might Americans be asked to forfeit when their heritage makes them suspect during a time of war?”

Whether students are asked to write essays or debate both sides of each question, they can gain experience in using logical reasoning and facts for civil debate and discourse.

A less intense writing activity would ask students to write a single diary entry for one of the children whose stories are told in the book. What was a day like for Mary Matsuda in a Japanese internment camp or Herb Karliner, a German Jewish boy expecting to sail to freedom and safety in the United States?

Herb Karliner, a German Jewish boy expecting to sail to freedom and safety

Herb Karliner, a German Jewish boy expecting to sail to freedom and safety in the United States in 1939

There are more stories about Chinese who came seeking gold in California in 1849 and cycles of Mexican migration in the 20th century. As Bausum concludes, “The United States has been alternatively welcoming and hostile to those who have tried to cross through ‘the golden door’ into America.”

While you are contemplating which of Ann Bausum’s books to share with your students, make plans to hear her in person at the Children’s Book Guild Nonfiction Award Celebration on April 29 at Clyde’s Gallery Place in Washington, D.C. Register here . Everyone is welcome!

http://childrensbookguild.org/karen-leggett-abouraya

Published on February 27, 2017 14:00

February 20, 2017

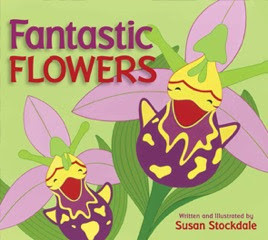

Fantastic Flowers as Mentor Text

Guest Post by Author/Illustrator Susan Stockdale

Let’s explore flowers that look like other things!

Fantastic Flowers celebrates 17 flowers from around the world that resemble objects, creatures and even people, from spiraling spoons to flying birds to sleeping babies. The rhythmic, rhyming text and bright, bold illustrations bring to life this dazzling display of surprising blooms. Fantastic Flowersencourages object identification and inspires children to observe nature more closely. Back matter provides information on the pollination process, color photos of the flowers (so children understand that they are real!) and a flower identification guide.

Before reading, show students the flower illustrations in the book. Ask them what they think the flowers resemble.

Writing prompts

• Write a paragraph about your favorite flower in the book, stating the reason you chose it.

• Select a flower in the book and generate two lists: one with adjectives (e.g. wild baboons) and one with verbs (e.g. skittering spiders) that describe it. Write a paragraph about the flower using your adjectives and verbs.

• Select a flower in the book and write a few sentences about it that integrates the information provided in the back matter, which includes the flowers’ common names, scientific names, native range (habitat) and pollinators.

• Create your own name for each flower, being as imaginative and playful as possible.

• Select two flowers in the book and imagine that they can speak. Write a few sentences imagining what they might “say” to one another in a conversation. For example, how might they compliment one another?

BIO: Susan Stockdale freelanced as a textile designer for the apparel industry before becoming the author and illustrator of 8 picture books for young children. Her books celebrate nature with exuberance and charm and have won awards from the American Library Association, Parents’ Choice, the National Science Teachers Association and Bank Street College of Education, among others. She lives with her husband in Chevy Chase, Maryland. Visit her website at www.susanstockdale.com.

BIO: Susan Stockdale freelanced as a textile designer for the apparel industry before becoming the author and illustrator of 8 picture books for young children. Her books celebrate nature with exuberance and charm and have won awards from the American Library Association, Parents’ Choice, the National Science Teachers Association and Bank Street College of Education, among others. She lives with her husband in Chevy Chase, Maryland. Visit her website at www.susanstockdale.com.

Let’s explore flowers that look like other things!

Fantastic Flowers celebrates 17 flowers from around the world that resemble objects, creatures and even people, from spiraling spoons to flying birds to sleeping babies. The rhythmic, rhyming text and bright, bold illustrations bring to life this dazzling display of surprising blooms. Fantastic Flowersencourages object identification and inspires children to observe nature more closely. Back matter provides information on the pollination process, color photos of the flowers (so children understand that they are real!) and a flower identification guide.

Before reading, show students the flower illustrations in the book. Ask them what they think the flowers resemble.

Writing prompts

• Write a paragraph about your favorite flower in the book, stating the reason you chose it.

• Select a flower in the book and generate two lists: one with adjectives (e.g. wild baboons) and one with verbs (e.g. skittering spiders) that describe it. Write a paragraph about the flower using your adjectives and verbs.

• Select a flower in the book and write a few sentences about it that integrates the information provided in the back matter, which includes the flowers’ common names, scientific names, native range (habitat) and pollinators.

• Create your own name for each flower, being as imaginative and playful as possible.

• Select two flowers in the book and imagine that they can speak. Write a few sentences imagining what they might “say” to one another in a conversation. For example, how might they compliment one another?

BIO: Susan Stockdale freelanced as a textile designer for the apparel industry before becoming the author and illustrator of 8 picture books for young children. Her books celebrate nature with exuberance and charm and have won awards from the American Library Association, Parents’ Choice, the National Science Teachers Association and Bank Street College of Education, among others. She lives with her husband in Chevy Chase, Maryland. Visit her website at www.susanstockdale.com.

BIO: Susan Stockdale freelanced as a textile designer for the apparel industry before becoming the author and illustrator of 8 picture books for young children. Her books celebrate nature with exuberance and charm and have won awards from the American Library Association, Parents’ Choice, the National Science Teachers Association and Bank Street College of Education, among others. She lives with her husband in Chevy Chase, Maryland. Visit her website at www.susanstockdale.com.

Published on February 20, 2017 14:00

February 13, 2017

"If I" Poem

by Jacqueline Jules

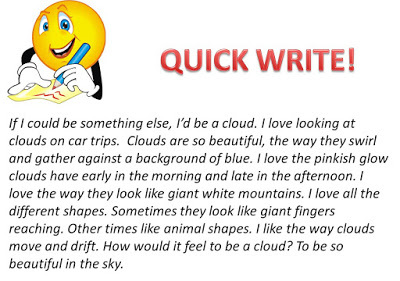

Writers of all ages are inspired by the simple suggestion to imagine themselves as a different entity. Model the process by using your own poem or my poem, “If I Were A Cloud.” I chose this subject because watching clouds is not only a joy but a consolation for me. Their floating beauty in the sky often lifts my spirits. To begin the exercise, ask your students to do a quick write on their chosen topic. Here is my quick write:

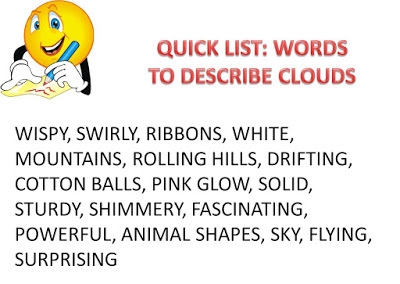

Then form a list of words that could be used in the poem to describe your feelings:

Finally, create the poem, using the line “If I were . . .” at the beginning of each stanza. Note that the poem does not have to rhyme. Encourage your students to choose figurative language over a forced rhyme scheme. It is more important to paint a picture for your reader than to rhyme. Here is an image of my poem, “If I Were a Cloud.”

[image error]

“If I Were a Cloud” is also online at Silver Birch Press.

In addition, or before you have students write individual poems, you might do a group writing exercise with the same process. Quick Write, Quick List of Words, Poem.

Have fun imagining!

www.jacquelinejules.com

Writers of all ages are inspired by the simple suggestion to imagine themselves as a different entity. Model the process by using your own poem or my poem, “If I Were A Cloud.” I chose this subject because watching clouds is not only a joy but a consolation for me. Their floating beauty in the sky often lifts my spirits. To begin the exercise, ask your students to do a quick write on their chosen topic. Here is my quick write:

Then form a list of words that could be used in the poem to describe your feelings:

Finally, create the poem, using the line “If I were . . .” at the beginning of each stanza. Note that the poem does not have to rhyme. Encourage your students to choose figurative language over a forced rhyme scheme. It is more important to paint a picture for your reader than to rhyme. Here is an image of my poem, “If I Were a Cloud.”

[image error]

“If I Were a Cloud” is also online at Silver Birch Press.

In addition, or before you have students write individual poems, you might do a group writing exercise with the same process. Quick Write, Quick List of Words, Poem.

Have fun imagining!

www.jacquelinejules.com

Published on February 13, 2017 14:00

February 6, 2017

Story Scenes: Just One Thing

by Nancy Viau

Anthony Pantaloni needs Just One Thing!—one thing he does well, one thing that will replace the Antsy Pants nickname he got tagged with the first day of fifth grade, one GOOD thing he can “own” before moving up to middle school next year. Every kid in Carpenter Elementary has something: Marcus is Mr. Athletic, Alexis is Smart Aleck, Bethany has her horse obsession, and even Cory can stake a claim as being the toughest kid in the whole school. Ant tries lots of things but – KA-BOOM! – nothing sticks! It doesn’t help that there are obstacles along the way—a baton-twirling teacher, an annoying cousin, and Dad’s new girlfriend to name a few.

“With tons of humor and lots of heart, this story jabs into the core of middle grade insanity and the question of whether or not a kid can ever make it out with even a little bit of self-esteem intact.” ~ T. Drecker (Bookworm for Kids) Discussion Guide for Teachers:

Follow-up Activity: Fold an 8 ½ x 11 plain piece paper in half long end to long end.Fold it again. And once more.Open sheet to find 8 blocks.Place paper on desk horizontally so that there are 4 blocks are across the top and 4 at the bottom.In the corners, number the blocks left to right so that #5 is the first number on the second row.Write KA-BOOM! somewhere on block #6.Students get together in pairs, and interview each other using the following questions:

What kinds of activities/sports/hobbies do you do well?

What activities /sports/hobbies do you wish you did well?

In terms of activities/sports/hobbies, what frustrates you?

If you’ve found your One Thing, what is it? Is that working out for you? How?

If you could change your One Thing, what would it be?

Next, using the divided paper, each student creates a visual representation of another student’s journey in finding his/her One Thing. Using the interview answers above as a guide, they write a scene (like a mini-story) in 8 blocks. Each block is illustrated and supported by minimal text. As for the climax, that occurs on block #6 where KA-BOOM! is written. Here, the writer shows the turn of events that leads to a final outcome on block #8. Students can base their story scenes on entirely on the interview and write a factual account, or use the answers for inspiration only and write absolute fiction.

BIO: Nancy Viau no longer worries about finding her One Thing for she has found quite a few things she loves, like being a mom, writing, traveling, and working as a librarian assistant. She is the author of the picture books City Street Beat, Look What I Can Do! and Storm Song, and an additional middle-grade novel, Samantha Hansen Has Rocks in Her Head. Nancy grew up in the suburbs of Philadelphia, PA and now resides in South Jersey. Vist Nancy at www.NancyViau.com www.KidLitAuthorsClub.com or Twitter: @NancyViau1

BIO: Nancy Viau no longer worries about finding her One Thing for she has found quite a few things she loves, like being a mom, writing, traveling, and working as a librarian assistant. She is the author of the picture books City Street Beat, Look What I Can Do! and Storm Song, and an additional middle-grade novel, Samantha Hansen Has Rocks in Her Head. Nancy grew up in the suburbs of Philadelphia, PA and now resides in South Jersey. Vist Nancy at www.NancyViau.com www.KidLitAuthorsClub.com or Twitter: @NancyViau1

Anthony Pantaloni needs Just One Thing!—one thing he does well, one thing that will replace the Antsy Pants nickname he got tagged with the first day of fifth grade, one GOOD thing he can “own” before moving up to middle school next year. Every kid in Carpenter Elementary has something: Marcus is Mr. Athletic, Alexis is Smart Aleck, Bethany has her horse obsession, and even Cory can stake a claim as being the toughest kid in the whole school. Ant tries lots of things but – KA-BOOM! – nothing sticks! It doesn’t help that there are obstacles along the way—a baton-twirling teacher, an annoying cousin, and Dad’s new girlfriend to name a few.

“With tons of humor and lots of heart, this story jabs into the core of middle grade insanity and the question of whether or not a kid can ever make it out with even a little bit of self-esteem intact.” ~ T. Drecker (Bookworm for Kids) Discussion Guide for Teachers:

Follow-up Activity: Fold an 8 ½ x 11 plain piece paper in half long end to long end.Fold it again. And once more.Open sheet to find 8 blocks.Place paper on desk horizontally so that there are 4 blocks are across the top and 4 at the bottom.In the corners, number the blocks left to right so that #5 is the first number on the second row.Write KA-BOOM! somewhere on block #6.Students get together in pairs, and interview each other using the following questions:

What kinds of activities/sports/hobbies do you do well?

What activities /sports/hobbies do you wish you did well?

In terms of activities/sports/hobbies, what frustrates you?

If you’ve found your One Thing, what is it? Is that working out for you? How?

If you could change your One Thing, what would it be?

Next, using the divided paper, each student creates a visual representation of another student’s journey in finding his/her One Thing. Using the interview answers above as a guide, they write a scene (like a mini-story) in 8 blocks. Each block is illustrated and supported by minimal text. As for the climax, that occurs on block #6 where KA-BOOM! is written. Here, the writer shows the turn of events that leads to a final outcome on block #8. Students can base their story scenes on entirely on the interview and write a factual account, or use the answers for inspiration only and write absolute fiction.

BIO: Nancy Viau no longer worries about finding her One Thing for she has found quite a few things she loves, like being a mom, writing, traveling, and working as a librarian assistant. She is the author of the picture books City Street Beat, Look What I Can Do! and Storm Song, and an additional middle-grade novel, Samantha Hansen Has Rocks in Her Head. Nancy grew up in the suburbs of Philadelphia, PA and now resides in South Jersey. Vist Nancy at www.NancyViau.com www.KidLitAuthorsClub.com or Twitter: @NancyViau1

BIO: Nancy Viau no longer worries about finding her One Thing for she has found quite a few things she loves, like being a mom, writing, traveling, and working as a librarian assistant. She is the author of the picture books City Street Beat, Look What I Can Do! and Storm Song, and an additional middle-grade novel, Samantha Hansen Has Rocks in Her Head. Nancy grew up in the suburbs of Philadelphia, PA and now resides in South Jersey. Vist Nancy at www.NancyViau.com www.KidLitAuthorsClub.com or Twitter: @NancyViau1

Published on February 06, 2017 14:00

Mary Quattlebaum's Blog

- Mary Quattlebaum's profile

- 22 followers

Mary Quattlebaum isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.