Mary Quattlebaum's Blog, page 5

February 26, 2018

Feeling Grumpy? Writing About Emotions

Guest Post by Courtney Pippin-Mathur

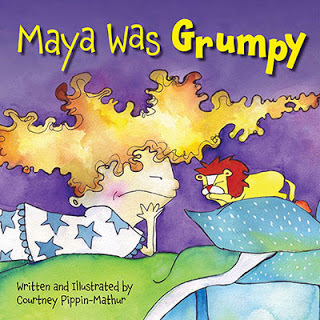

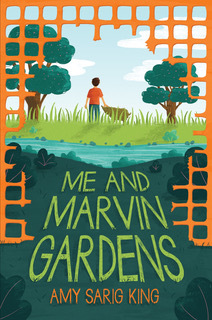

Ever wake up in “a crispy, crunchy grumpy” mood? That’s what happens in Maya Was Grumpy, a picture book I wrote and illustrated. Sometimes you just wake up on the wrong side of the bed and that is exactly what happens to Maya. She’s not sure why she’s not into coloring, wearing her favorite clothes or eating her favorite snack but all she wants to go is grump around the house and share her bad mood.

Luckily, her grandmother is there to help Maya get less grumpy by pointing out all of the wild adventures they are missing out on because of Maya’s grumps. With each wild suggestion, Maya starts to feel a bit better until she is finally ready to go play.

Emotions rule our lives, especially as children. Use the text to discuss different emotions and how they affect a story.-Why is Maya grumpy? -Do you ever wake up in a bad mood? Or Sad? -Write a story based on just one emotion and how it might affect your day.

Maya is a fun read aloud with lots of alliteration and sometimes unusual words to describe Maya’s sour moods. -Brainstorm fun words to describe moods besides the first ones you think of. -Instead of happy, what about jubilant? Instead of sad, what about morose?-Play with word sounds. Alliteration is a poetic sound device that makes reading fun.-Write a first draft of a paragraph about a simple story. On the second draft, write a paragraph using as many types of alliteration or assonance or just fun sounding words as you can think of.

There are clues in the artwork that sometimes aren’t stated in the story. These little details are what makes a picture book fun! -What is something that you notice about Maya’s hair and how it reacts to her mood?- On the playground spread do you see all of the animals Maya’s grandma mentioned? -Do you think she was inspired by the animals in her stories? - What are some real-life things you can change or exaggerate to make a fun story?

*Bonus- There is an Activity page on my site where you can color a picture of Maya and draw what you think caused her bad mood.

BIO: Courtney Pippin-Mathur was born and raised in East Texas but now lives on the East Coast. She shares her house with a knight, a princess and two dragons. This leads to many exciting adventures with lots of breaks for reading. She has written and illustrated two picture books, Maya Was Grumpy and Dragons Rule, Princesses Drool! Visit her online at http://www.pippinmathur.com/

BIO: Courtney Pippin-Mathur was born and raised in East Texas but now lives on the East Coast. She shares her house with a knight, a princess and two dragons. This leads to many exciting adventures with lots of breaks for reading. She has written and illustrated two picture books, Maya Was Grumpy and Dragons Rule, Princesses Drool! Visit her online at http://www.pippinmathur.com/

Ever wake up in “a crispy, crunchy grumpy” mood? That’s what happens in Maya Was Grumpy, a picture book I wrote and illustrated. Sometimes you just wake up on the wrong side of the bed and that is exactly what happens to Maya. She’s not sure why she’s not into coloring, wearing her favorite clothes or eating her favorite snack but all she wants to go is grump around the house and share her bad mood.

Luckily, her grandmother is there to help Maya get less grumpy by pointing out all of the wild adventures they are missing out on because of Maya’s grumps. With each wild suggestion, Maya starts to feel a bit better until she is finally ready to go play.

Emotions rule our lives, especially as children. Use the text to discuss different emotions and how they affect a story.-Why is Maya grumpy? -Do you ever wake up in a bad mood? Or Sad? -Write a story based on just one emotion and how it might affect your day.

Maya is a fun read aloud with lots of alliteration and sometimes unusual words to describe Maya’s sour moods. -Brainstorm fun words to describe moods besides the first ones you think of. -Instead of happy, what about jubilant? Instead of sad, what about morose?-Play with word sounds. Alliteration is a poetic sound device that makes reading fun.-Write a first draft of a paragraph about a simple story. On the second draft, write a paragraph using as many types of alliteration or assonance or just fun sounding words as you can think of.

There are clues in the artwork that sometimes aren’t stated in the story. These little details are what makes a picture book fun! -What is something that you notice about Maya’s hair and how it reacts to her mood?- On the playground spread do you see all of the animals Maya’s grandma mentioned? -Do you think she was inspired by the animals in her stories? - What are some real-life things you can change or exaggerate to make a fun story?

*Bonus- There is an Activity page on my site where you can color a picture of Maya and draw what you think caused her bad mood.

BIO: Courtney Pippin-Mathur was born and raised in East Texas but now lives on the East Coast. She shares her house with a knight, a princess and two dragons. This leads to many exciting adventures with lots of breaks for reading. She has written and illustrated two picture books, Maya Was Grumpy and Dragons Rule, Princesses Drool! Visit her online at http://www.pippinmathur.com/

BIO: Courtney Pippin-Mathur was born and raised in East Texas but now lives on the East Coast. She shares her house with a knight, a princess and two dragons. This leads to many exciting adventures with lots of breaks for reading. She has written and illustrated two picture books, Maya Was Grumpy and Dragons Rule, Princesses Drool! Visit her online at http://www.pippinmathur.com/

Published on February 26, 2018 14:00

February 12, 2018

Writing Connections with Amy Sarig King

by Mary Quattlebaum

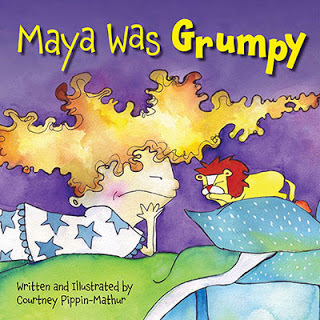

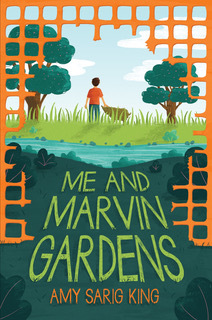

Amy Sarig King is the author of many acclaimed YA novels, but Me and Marvin Gardens (Scholastic, 2017) is her first middle-grade novel. It garnered three starred reviews and was named a 2017 Best Book by the Washington Post.

In an interview with the KidsPost section of the Washington Post, King talks about the childhood experiences that informed the book. She mentions her dog, Stella, as her inspiration for the mysterious creature that gets young readers thinking about recycling in a whole different way.

Obe loves the cornfields that his family once owned, but now they are being turned into a housing development. And his best friend is ditching him for the new kids in the neighborhood. To add to his troubles, Obe discovers a new type of animal by the creek—a slimy tapir-like creature with the friendly personality of a dog. He names it Marvin Gardens. Before long, Obe realizes that the creature eats plastic but that its toxic poop is ruining the land. Can Obe trust his science teacher, Ms. G, to help with the situation?

Below are writing lessons for the classroom or for individual writers ages 8 and up.

FACTS AS INSPIRATION: Classroom Discussion, Part 1: In the book, Ms. G shares facts about the environment with her students. As she researched these facts, King herself was horrified to discover that it takes a plastic bottle 500 years to decompose, and that Americans throw away 2.5 million of these bottles per hour. King created Marvin Gardens as a character that seemingly solves the problem (by eating plastic) but creates another (the toxic chemicals excreted as waste destroy grass, tennis shoes, and pretty much whatever comes in contact with them).

Classroom Writing, Part 1: Ask students to research several facts about dangers posed to the environment. For example, habitat loss for cheetahs is pushing them toward extinction in the wild. Or they might choose one of Ms. G’s facts from the book.

Have them choose one problem and brainstorm ways to solve it. Encourage them to make these solutions as helpful as they can, even if they may be extreme or somewhat wacky. (For example, a plastic-eating animal is a rather extreme solution to littering/recycling issues!)

Ask students to give their solution a name (such as Marvin Gardens), write one or two paragraphs on how it would work, and draw a picture or diagram of it.

Classroom Writing, Part 2, Critical Thinking and Writing: Might this solution create other problems? List some possible resulting problems. How might they be solved?

TAKING ACTION, Classroom Discussion, Part 1: Ask the class to notice environmental problems that are in the school or grounds for two days. For example, leaky faucets in bathrooms, lack of recycling bins, litter on school grounds, lack of native plants for local pollinators. List these things on the board.

Brainstorm ways to address or solve them. Have the class identify 2 or 3 that they might take action on and help them develop a strategy to do so.

Have them do online research to discover how other students or activist groups have created positive change in these problem areas.

Ask for volunteers to write a short article for the school newspaper or bulletin or principal’s blog and an op-ed piece for the local newspaper.

www.maryquattlebaum.com

Amy Sarig King is the author of many acclaimed YA novels, but Me and Marvin Gardens (Scholastic, 2017) is her first middle-grade novel. It garnered three starred reviews and was named a 2017 Best Book by the Washington Post.

In an interview with the KidsPost section of the Washington Post, King talks about the childhood experiences that informed the book. She mentions her dog, Stella, as her inspiration for the mysterious creature that gets young readers thinking about recycling in a whole different way.

Obe loves the cornfields that his family once owned, but now they are being turned into a housing development. And his best friend is ditching him for the new kids in the neighborhood. To add to his troubles, Obe discovers a new type of animal by the creek—a slimy tapir-like creature with the friendly personality of a dog. He names it Marvin Gardens. Before long, Obe realizes that the creature eats plastic but that its toxic poop is ruining the land. Can Obe trust his science teacher, Ms. G, to help with the situation?

Below are writing lessons for the classroom or for individual writers ages 8 and up.

FACTS AS INSPIRATION: Classroom Discussion, Part 1: In the book, Ms. G shares facts about the environment with her students. As she researched these facts, King herself was horrified to discover that it takes a plastic bottle 500 years to decompose, and that Americans throw away 2.5 million of these bottles per hour. King created Marvin Gardens as a character that seemingly solves the problem (by eating plastic) but creates another (the toxic chemicals excreted as waste destroy grass, tennis shoes, and pretty much whatever comes in contact with them).

Classroom Writing, Part 1: Ask students to research several facts about dangers posed to the environment. For example, habitat loss for cheetahs is pushing them toward extinction in the wild. Or they might choose one of Ms. G’s facts from the book.

Have them choose one problem and brainstorm ways to solve it. Encourage them to make these solutions as helpful as they can, even if they may be extreme or somewhat wacky. (For example, a plastic-eating animal is a rather extreme solution to littering/recycling issues!)

Ask students to give their solution a name (such as Marvin Gardens), write one or two paragraphs on how it would work, and draw a picture or diagram of it.

Classroom Writing, Part 2, Critical Thinking and Writing: Might this solution create other problems? List some possible resulting problems. How might they be solved?

TAKING ACTION, Classroom Discussion, Part 1: Ask the class to notice environmental problems that are in the school or grounds for two days. For example, leaky faucets in bathrooms, lack of recycling bins, litter on school grounds, lack of native plants for local pollinators. List these things on the board.

Brainstorm ways to address or solve them. Have the class identify 2 or 3 that they might take action on and help them develop a strategy to do so.

Have them do online research to discover how other students or activist groups have created positive change in these problem areas.

Ask for volunteers to write a short article for the school newspaper or bulletin or principal’s blog and an op-ed piece for the local newspaper.

www.maryquattlebaum.com

Published on February 12, 2018 14:00

January 29, 2018

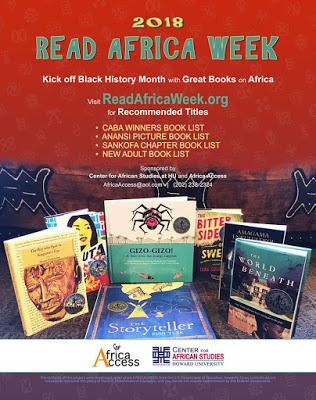

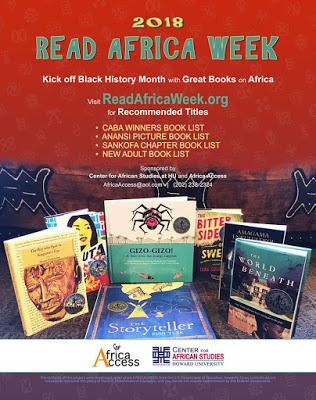

Read Africa

by Karen Leggett Abouraya

It’s almost Read Africa Week – that first week of February when Africa Access encourages everyone to kick off Black History Month with great books about Africa. There are lots of resources and booklists online, including the 2017 Children’s Africana Book Awards.

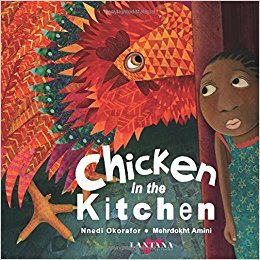

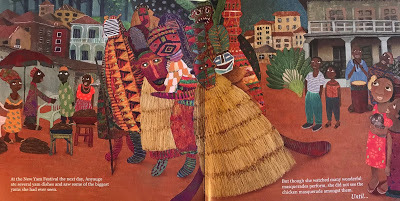

Let’s look at Chicken in the Kitchen, by Nnedi Okorafor, illustrated by Mehrdokht Amini (Lantana Publishing). Okorafor shares the masquerade culture of West Africa through a young Nigerian girl who fears – then adores – the giant chicken in her kitchen.

· Ask students to write about someone they didn’t know or someone who scared them (even just a little) who later became a friend (or at least less scary). How did the change happen? How does that affect the way you meet new people now?

Chicken in the Kitchenalso provides opportunities to talk about visual literacy. With Instagram stories and Snapchat images, television news and Twitter photos, images can galvanize a nation and even the world. Are young people learning to interpret, gather information and take meaning effectively from images?

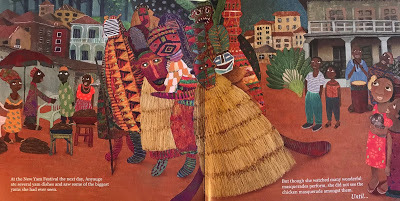

· What does this image in Chicken in the Kitchen tell the reader about Anyaugo’s community? Here’s what the Africa Access reviewer noticed. See how many of these observations your students notice.

o “To the left we see two couples in traditional dress symbolizing gender parity in the production of yams; to the right musicians, also in traditional dress, play local instruments. The backdrop shows a town with houses and apartments rather than a rural setting. The children attending the masquerade sport Western dress and local designs.”

· How do pictures help tell the story of Anyaugo and the chicken? Notice for example, how the Wood Wit appears in images before being mentioned in the text. How many Wood Wit images can your students find?

o Ask children to write a letter to the Wood Wit asking for help with a task – and then pretend they are the Wood Wit and write a response. This could be a group project as well.

In my book Hands Around the Library: Protecting Egypt’s Treasured Books (a 2013 CABA winner) and its accompanying website, there are news photos from the 2011 Egyptian revolution that illustrator Susan L. Roth translated into cut-paper collages, adding rich interpretations to the story.

· Ask students to choose an interesting news photo or image and re-create it as a drawing, painting or collage. You can also provide random news photos to students and ask them to write a caption or paragraph; then compare their writing to an actual news account of the event in the photo.

Read Africa Week is an opportunity to focus attention on individual countries and stories from a continent many Americans know little about. It is also an opportunity to begin adding these stories to your year-round reading lists – along with attention to the increasing importance of visual literacy.

It’s almost Read Africa Week – that first week of February when Africa Access encourages everyone to kick off Black History Month with great books about Africa. There are lots of resources and booklists online, including the 2017 Children’s Africana Book Awards.

Let’s look at Chicken in the Kitchen, by Nnedi Okorafor, illustrated by Mehrdokht Amini (Lantana Publishing). Okorafor shares the masquerade culture of West Africa through a young Nigerian girl who fears – then adores – the giant chicken in her kitchen.

· Ask students to write about someone they didn’t know or someone who scared them (even just a little) who later became a friend (or at least less scary). How did the change happen? How does that affect the way you meet new people now?

Chicken in the Kitchenalso provides opportunities to talk about visual literacy. With Instagram stories and Snapchat images, television news and Twitter photos, images can galvanize a nation and even the world. Are young people learning to interpret, gather information and take meaning effectively from images?

· What does this image in Chicken in the Kitchen tell the reader about Anyaugo’s community? Here’s what the Africa Access reviewer noticed. See how many of these observations your students notice.

o “To the left we see two couples in traditional dress symbolizing gender parity in the production of yams; to the right musicians, also in traditional dress, play local instruments. The backdrop shows a town with houses and apartments rather than a rural setting. The children attending the masquerade sport Western dress and local designs.”

· How do pictures help tell the story of Anyaugo and the chicken? Notice for example, how the Wood Wit appears in images before being mentioned in the text. How many Wood Wit images can your students find?

o Ask children to write a letter to the Wood Wit asking for help with a task – and then pretend they are the Wood Wit and write a response. This could be a group project as well.

In my book Hands Around the Library: Protecting Egypt’s Treasured Books (a 2013 CABA winner) and its accompanying website, there are news photos from the 2011 Egyptian revolution that illustrator Susan L. Roth translated into cut-paper collages, adding rich interpretations to the story.

· Ask students to choose an interesting news photo or image and re-create it as a drawing, painting or collage. You can also provide random news photos to students and ask them to write a caption or paragraph; then compare their writing to an actual news account of the event in the photo.

Read Africa Week is an opportunity to focus attention on individual countries and stories from a continent many Americans know little about. It is also an opportunity to begin adding these stories to your year-round reading lists – along with attention to the increasing importance of visual literacy.

Published on January 29, 2018 14:00

January 15, 2018

Earth's Point of View

by Laura Gehl

Get your class thinking about writing fun, humorous nonfiction with Stacy McAnulty’s Earth: My First 4.54 Billion Years (illustrated by David Litchfield).

After you read Earth out loud, here are some ideas for getting your students writing:

1) Earth is written in first person, from Earth’s point of view. Think of an object in your classroom. Write about the school day from the point of view of that object. Make sure to show your object’s personality in your writing…is the object shy? A know-it-all? Silly? Vain?

2) Earth tells the life story of our planet. Whose life story would you like to tell? Pick a person, object, or animal in your life, and write a short autobiography. (Hint: before you start writing, you will need to decide what are the most important events and details to share…you can’t include everything, or your story will be too long and boring!)

3) At the end of the book Earth, author Stacy McAnulty has a funny note addressed to an “alien visitor.” What if an alien visited Earth and it was YOUR job to teach that alien everything important about our planet? Write a speech, make a pamphlet or poster, draw a cartoon…use your creativity to show what facts you would tell the alien visitor about Earth, and how you would make those facts seem interesting to your audience!

www.lauragehl.com

Get your class thinking about writing fun, humorous nonfiction with Stacy McAnulty’s Earth: My First 4.54 Billion Years (illustrated by David Litchfield).

After you read Earth out loud, here are some ideas for getting your students writing:

1) Earth is written in first person, from Earth’s point of view. Think of an object in your classroom. Write about the school day from the point of view of that object. Make sure to show your object’s personality in your writing…is the object shy? A know-it-all? Silly? Vain?

2) Earth tells the life story of our planet. Whose life story would you like to tell? Pick a person, object, or animal in your life, and write a short autobiography. (Hint: before you start writing, you will need to decide what are the most important events and details to share…you can’t include everything, or your story will be too long and boring!)

3) At the end of the book Earth, author Stacy McAnulty has a funny note addressed to an “alien visitor.” What if an alien visited Earth and it was YOUR job to teach that alien everything important about our planet? Write a speech, make a pamphlet or poster, draw a cartoon…use your creativity to show what facts you would tell the alien visitor about Earth, and how you would make those facts seem interesting to your audience!

www.lauragehl.com

Published on January 15, 2018 14:00

January 1, 2018

Fish in a Tree

by Karen Leggett Abouraya

Fish in a Treeby Linda Mullaly Hunt (Puffin, 2015) features several middle schoolers who don’t fit in – as well as a pair of girls who tease all the others mercilessly. Ally is at the center of it all, spending as much time in the office as in class because she makes inappropriate comments or no comments at all and often creates a problem to avoid doing work she finds difficult. She talks about the mind movies in her brain: “My mind does this all the time – shows me these movies that seem so real that they carry me away inside of them. They are a relief from my real life.”

Ally’s real life includes frequent headaches and “letters that dance and move on the page.” When a new teacher gave her a journal to write in every day, she thought she’d rather eat grass. She draws instead. An observant teacher finally realizes Ally has dyslexia and slowly life begins to be worth living.

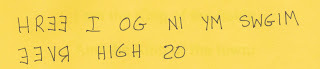

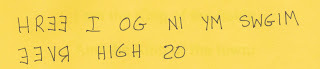

Fish in a Tree provides many openings for thought-provoking discussions and writing (or drawing) that could help students become more sensitive to each other’s problems – or aware of their own. For example, ask students if they can read the words in this phrase:

The phrase says, “Here I go in my swing” but it looks like the jumble above to a child with dyslexia.

The teacher, Mr. Daniels, had commented that, “If you judge a fish on its ability to climb a tree, it will spend its whole life thinking that it’s stupid.” After reading the book, ask students to figure out what the teacher means and how it applies to Ally – or perhaps themselves.

Ally suffered for a long time without letting anyone know she had problems reading. · Why is it so hard to ask for help when we need it?· Why do certain kids always tease and make life difficult for those who are different?

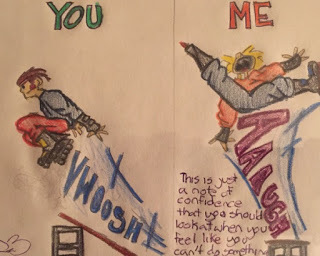

Ask each student to write a paragraph or a poem or draw a picture about some task or activity that is difficult or challenging for them. · If this is an activity you have to do – like reading or math – how do you solve the challenge? Who helps you, if anyone? What kind of help would you like?

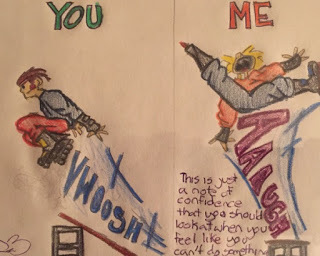

In this picture, a young boy shows that he is not as skilled as his friend on the skateboard but he certainly showed what a wonderful artist he is! Everybody is smart in different ways.

Fish in a Tree won the Schneider Family Book Award in 2016 as a book that embodies an artistic expression of the disability experience for child and adolescent audiences.

Fish in a Treeby Linda Mullaly Hunt (Puffin, 2015) features several middle schoolers who don’t fit in – as well as a pair of girls who tease all the others mercilessly. Ally is at the center of it all, spending as much time in the office as in class because she makes inappropriate comments or no comments at all and often creates a problem to avoid doing work she finds difficult. She talks about the mind movies in her brain: “My mind does this all the time – shows me these movies that seem so real that they carry me away inside of them. They are a relief from my real life.”

Ally’s real life includes frequent headaches and “letters that dance and move on the page.” When a new teacher gave her a journal to write in every day, she thought she’d rather eat grass. She draws instead. An observant teacher finally realizes Ally has dyslexia and slowly life begins to be worth living.

Fish in a Tree provides many openings for thought-provoking discussions and writing (or drawing) that could help students become more sensitive to each other’s problems – or aware of their own. For example, ask students if they can read the words in this phrase:

The phrase says, “Here I go in my swing” but it looks like the jumble above to a child with dyslexia.

The teacher, Mr. Daniels, had commented that, “If you judge a fish on its ability to climb a tree, it will spend its whole life thinking that it’s stupid.” After reading the book, ask students to figure out what the teacher means and how it applies to Ally – or perhaps themselves.

Ally suffered for a long time without letting anyone know she had problems reading. · Why is it so hard to ask for help when we need it?· Why do certain kids always tease and make life difficult for those who are different?

Ask each student to write a paragraph or a poem or draw a picture about some task or activity that is difficult or challenging for them. · If this is an activity you have to do – like reading or math – how do you solve the challenge? Who helps you, if anyone? What kind of help would you like?

In this picture, a young boy shows that he is not as skilled as his friend on the skateboard but he certainly showed what a wonderful artist he is! Everybody is smart in different ways.

Fish in a Tree won the Schneider Family Book Award in 2016 as a book that embodies an artistic expression of the disability experience for child and adolescent audiences.

Published on January 01, 2018 14:00

December 11, 2017

It’s a Parody Party!

guest post by Sue Fliess

Okay, so maybe I get overly giddy about writing parodies, but for me they are just so much fun! I’m not sure what inspired me to write my first parody song, but once I did, I was hooked. Essentially, I like to take popular songs and change up the lyrics to make it about writing or poke fun at part of the writing journey. I think it’s cathartic to me to be able to express some of the less appealing parts of being in book publishing or being a writer. Humor gets me through the rough patches, and I figured others in the same boat might need a laugh. I’ve done parodies on finishing a book, revising, wanting more books, and even dipped my toe into the political spectrum. But I had not thought of doing a parody for a book, which seems hard to believe! So when an editor, who’d seen my parodies, asked me to try my hand at a parody for a children’s book, I said yes! And We Wish For A Monster Christmas was born!

Try it with your class!Depending on the age of your students, you can have them do simple or more complex parodies. For the younger set, maybe just take the title of songs they know, and have them change the titles, or just the main chorus. For older groups they can choose a song and rewrite all the lyrics. What I do is print out a page with 2 columns. The left column I have the actual song lyrics and on the right, I create my own to match the beats or syllables. But since it’s a parody, it doesn’t have to be exact. Also, my parodies surround a central theme, but for younger students, it may be a challenge to rewrite a whole song around one topic.

Literary parodyNot in the mood for music? Have your class write a parody of a nursery rhyme or poem they know from a collection. For instance, Mary Had a Little Lamb or Humpty Dumpty might be good starters. Again, they can just create a new title, or rework the whole piece.

No matter which direction you choose, it’s sure to be a fun activity that lets kids be silly and use their imaginations.

Sue Fliess ("fleece") is the author of numerous children's books including A Fairy Friend, Calling All Cars, Robots, Robots Everywhere!, The Hug Book, Tons of Trucks and Shoes for Me! Sue lives with her family and a Labrador named Charlie in Northern Virginia. For more information about Sue and to check out her books and song parodies, go to http://www.suefliess.com/

Sue Fliess ("fleece") is the author of numerous children's books including A Fairy Friend, Calling All Cars, Robots, Robots Everywhere!, The Hug Book, Tons of Trucks and Shoes for Me! Sue lives with her family and a Labrador named Charlie in Northern Virginia. For more information about Sue and to check out her books and song parodies, go to http://www.suefliess.com/

Okay, so maybe I get overly giddy about writing parodies, but for me they are just so much fun! I’m not sure what inspired me to write my first parody song, but once I did, I was hooked. Essentially, I like to take popular songs and change up the lyrics to make it about writing or poke fun at part of the writing journey. I think it’s cathartic to me to be able to express some of the less appealing parts of being in book publishing or being a writer. Humor gets me through the rough patches, and I figured others in the same boat might need a laugh. I’ve done parodies on finishing a book, revising, wanting more books, and even dipped my toe into the political spectrum. But I had not thought of doing a parody for a book, which seems hard to believe! So when an editor, who’d seen my parodies, asked me to try my hand at a parody for a children’s book, I said yes! And We Wish For A Monster Christmas was born!

Try it with your class!Depending on the age of your students, you can have them do simple or more complex parodies. For the younger set, maybe just take the title of songs they know, and have them change the titles, or just the main chorus. For older groups they can choose a song and rewrite all the lyrics. What I do is print out a page with 2 columns. The left column I have the actual song lyrics and on the right, I create my own to match the beats or syllables. But since it’s a parody, it doesn’t have to be exact. Also, my parodies surround a central theme, but for younger students, it may be a challenge to rewrite a whole song around one topic.

Literary parodyNot in the mood for music? Have your class write a parody of a nursery rhyme or poem they know from a collection. For instance, Mary Had a Little Lamb or Humpty Dumpty might be good starters. Again, they can just create a new title, or rework the whole piece.

No matter which direction you choose, it’s sure to be a fun activity that lets kids be silly and use their imaginations.

Sue Fliess ("fleece") is the author of numerous children's books including A Fairy Friend, Calling All Cars, Robots, Robots Everywhere!, The Hug Book, Tons of Trucks and Shoes for Me! Sue lives with her family and a Labrador named Charlie in Northern Virginia. For more information about Sue and to check out her books and song parodies, go to http://www.suefliess.com/

Sue Fliess ("fleece") is the author of numerous children's books including A Fairy Friend, Calling All Cars, Robots, Robots Everywhere!, The Hug Book, Tons of Trucks and Shoes for Me! Sue lives with her family and a Labrador named Charlie in Northern Virginia. For more information about Sue and to check out her books and song parodies, go to http://www.suefliess.com/

Published on December 11, 2017 14:00

November 27, 2017

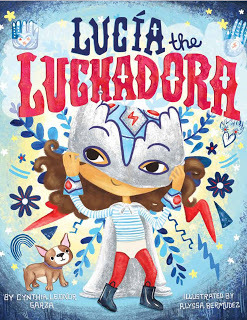

Lucía the Luchadora

Guest Post by Cynthia Leonor Garza

My new picture book, Lucía the Luchadora, illustrated by Alyssa Bermudez, is about a little girl who wants to be a superhero. When Lucía is told by the boys that girls can’t be superheroes, she gets mad, spicy mad, but with the help of abuela, comes up with an ingenious plan. She returns to the playground with her identity concealed behind a lucha libre mask and cape and becomes a playground sensation. Soon, all the other kids are dressed up as luchadores, too, but when Lucía witnesses the boys telling another girl she can’t be a superhero, Lucía must make a decision: Remain hidden behind the mask or reveal her true identity, which a real luchadoramust never do.

There are lots of ways this book can be used in the classroom to teach both younger and older students and English language learners. Dr. Rebecca Palacios, an inductee of the National Teachers Hall of Fame and preschool educator for over 30 years, developed a curriculum guide to go along with the book. Here are some activities drawn from the guide:

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL CONNECTIONS: After reading Lucía the Luchadora, explore social-emotional questions by asking:

· At times Lucía felt “mad, spicy mad.” Why did she feel this way? How did she resolve her feelings? · Lucía felt so strong with her mask on. Why do you think she felt this way? · How did Lucía help the pink crusader who felt so sad? Why was this important for her to do? · Why are feelings important in our lives? How can we help others with their feelings? ONOMATOPOEIA: Lucía the Luchadora also has lots of fun onomatopoeia like POW and BAM! Have a ten-minute word scavenger hunt to find these words. Discuss what they mean. How do these words affect the story?CULTURE: Explore the cultural aspects of the book. Look at the illustrations and have students find pictures they don’t recognize or words in Spanish. What might those pictures represent, and what do the Spanish words mean?There is also an Author’s Note on luchadores, luchadoras and lucha libre at the end of the book as well as an illustration of lucha libre legend El Santo inside the book. Have older students research a famous luchador or luchadora. What is the difference between a rudo and técnico? Where do luchadores today live? What are they fighting for? Why is the mask so important in Mexican wrestling?STEM & ART: Have some art and math fun by having the students create their own masks. Have them engineer a design and figure out how to fit a mask on a face. Discuss the symmetry of the design and which tools and resources would be best for creating such a mask. Have the students use geometric figures to make their masks, and incorporate some of art and design elements from the book. Last, everyone needs a lucha libre name. Have students write about a fun alter ego! BIO: Cynthia Leonor Garza spent most of her childhood under the hot South Texas sun running around with her three brothers. She's a journalist who has worked for several newspapers and her commentaries have appeared on NPR and in The Atlantic. Of all the lucha libre masks she owns, her favorite one is pink and gold. She currently lives with her two young daughters and husband in Nairobi, Kenya. Lucía the Luchadora is her first picture book.

BIO: Cynthia Leonor Garza spent most of her childhood under the hot South Texas sun running around with her three brothers. She's a journalist who has worked for several newspapers and her commentaries have appeared on NPR and in The Atlantic. Of all the lucha libre masks she owns, her favorite one is pink and gold. She currently lives with her two young daughters and husband in Nairobi, Kenya. Lucía the Luchadora is her first picture book.

My new picture book, Lucía the Luchadora, illustrated by Alyssa Bermudez, is about a little girl who wants to be a superhero. When Lucía is told by the boys that girls can’t be superheroes, she gets mad, spicy mad, but with the help of abuela, comes up with an ingenious plan. She returns to the playground with her identity concealed behind a lucha libre mask and cape and becomes a playground sensation. Soon, all the other kids are dressed up as luchadores, too, but when Lucía witnesses the boys telling another girl she can’t be a superhero, Lucía must make a decision: Remain hidden behind the mask or reveal her true identity, which a real luchadoramust never do.

There are lots of ways this book can be used in the classroom to teach both younger and older students and English language learners. Dr. Rebecca Palacios, an inductee of the National Teachers Hall of Fame and preschool educator for over 30 years, developed a curriculum guide to go along with the book. Here are some activities drawn from the guide:

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL CONNECTIONS: After reading Lucía the Luchadora, explore social-emotional questions by asking:

· At times Lucía felt “mad, spicy mad.” Why did she feel this way? How did she resolve her feelings? · Lucía felt so strong with her mask on. Why do you think she felt this way? · How did Lucía help the pink crusader who felt so sad? Why was this important for her to do? · Why are feelings important in our lives? How can we help others with their feelings? ONOMATOPOEIA: Lucía the Luchadora also has lots of fun onomatopoeia like POW and BAM! Have a ten-minute word scavenger hunt to find these words. Discuss what they mean. How do these words affect the story?CULTURE: Explore the cultural aspects of the book. Look at the illustrations and have students find pictures they don’t recognize or words in Spanish. What might those pictures represent, and what do the Spanish words mean?There is also an Author’s Note on luchadores, luchadoras and lucha libre at the end of the book as well as an illustration of lucha libre legend El Santo inside the book. Have older students research a famous luchador or luchadora. What is the difference between a rudo and técnico? Where do luchadores today live? What are they fighting for? Why is the mask so important in Mexican wrestling?STEM & ART: Have some art and math fun by having the students create their own masks. Have them engineer a design and figure out how to fit a mask on a face. Discuss the symmetry of the design and which tools and resources would be best for creating such a mask. Have the students use geometric figures to make their masks, and incorporate some of art and design elements from the book. Last, everyone needs a lucha libre name. Have students write about a fun alter ego!

BIO: Cynthia Leonor Garza spent most of her childhood under the hot South Texas sun running around with her three brothers. She's a journalist who has worked for several newspapers and her commentaries have appeared on NPR and in The Atlantic. Of all the lucha libre masks she owns, her favorite one is pink and gold. She currently lives with her two young daughters and husband in Nairobi, Kenya. Lucía the Luchadora is her first picture book.

BIO: Cynthia Leonor Garza spent most of her childhood under the hot South Texas sun running around with her three brothers. She's a journalist who has worked for several newspapers and her commentaries have appeared on NPR and in The Atlantic. Of all the lucha libre masks she owns, her favorite one is pink and gold. She currently lives with her two young daughters and husband in Nairobi, Kenya. Lucía the Luchadora is her first picture book.

Published on November 27, 2017 14:00

November 13, 2017

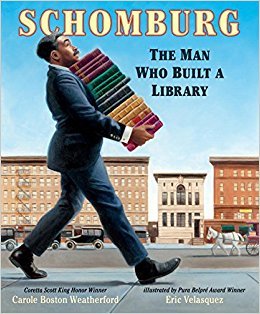

Schomburg: The Man Who Built a Library

by Karen Leggett Abouraya

As a boy in Puerto Rico, Arturo Schomburg’s fifth grade teacher told him that “Africa’s sons and daughters had no history, no heroes worth noting.” But in her new picture book Schomburg: The Man Who Built a Library (Candlewick, 2017), Carole Boston Weatherford writes,

“After that teacher dismissed his people’s past, did the twinkle leave Arturo’s eyeslike a candle blown out in the dark?No, the twinkle never left. It grew into a spark.”

That spark led Schomburg to collect a life’s worth of books, letters, art and prints that told the story of African accomplishments all over the world, especially Africans who came to the New World – like Toussaint Louverture who led a slave revolt in Haiti and Paul Cuffee who was one of the richest black men in early America. Schomburg found African roots in the family trees of naturalist John James Audubon and composer Ludwig van Beethoven. When Schomburg’s collection outgrew his house, the Carnegie Corporation bought everything for $10,000 and donated it to the New York Public Library.

This book opens the door for students to learn and write about the unsung heroes Schomburg discovered but also others from their own ethnic backgrounds.

· Learn and write a little more about someone in the book you’ve never heard of.· Research someone from your own ethnic background who came to America and made a difference. · Write a paragraph or a poem about someone you admire – either from your own ethnic background or someone else’s.

Arturo immigrated to New York from Puerto Rico in 1891, when he was 17 years old. He carried with him letters of introduction to help him find work.

Arturo immigrated to New York from Puerto Rico in 1891, when he was 17 years old. He carried with him letters of introduction to help him find work.

· Students can work in pairs to write letters of introduction for each other. Each student imagines a future job and writes a letter recommending the other student for that chosen career. What qualities and skills would be important? What would convince someone to hire the person?

“Arturo Schomburg studied the past… His mission looked to the future. ‘I am proud,’ said Schomburg, ‘to be able to do something that may mean inspiration for the youth of my race.’” He told professors to “include the practical history of the Negro race from the dawn of civilization to the present time. Then young blacks would hold their heads high and view themselves as anyone’s equal.”

Schomburg’s collection became the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library. Earlier this year, the Center was designated a national historic landmark.

· Is your school named after a person? Learn and write something about that person.· What type of building or space would you want named after you?

If these projects are initiated early in the school year, students can be encouraged to look for people whose stories are not well known in all their classes.

https://childrensbookguild.org/karen-leggett-abouraya

As a boy in Puerto Rico, Arturo Schomburg’s fifth grade teacher told him that “Africa’s sons and daughters had no history, no heroes worth noting.” But in her new picture book Schomburg: The Man Who Built a Library (Candlewick, 2017), Carole Boston Weatherford writes,

“After that teacher dismissed his people’s past, did the twinkle leave Arturo’s eyeslike a candle blown out in the dark?No, the twinkle never left. It grew into a spark.”

That spark led Schomburg to collect a life’s worth of books, letters, art and prints that told the story of African accomplishments all over the world, especially Africans who came to the New World – like Toussaint Louverture who led a slave revolt in Haiti and Paul Cuffee who was one of the richest black men in early America. Schomburg found African roots in the family trees of naturalist John James Audubon and composer Ludwig van Beethoven. When Schomburg’s collection outgrew his house, the Carnegie Corporation bought everything for $10,000 and donated it to the New York Public Library.

This book opens the door for students to learn and write about the unsung heroes Schomburg discovered but also others from their own ethnic backgrounds.

· Learn and write a little more about someone in the book you’ve never heard of.· Research someone from your own ethnic background who came to America and made a difference. · Write a paragraph or a poem about someone you admire – either from your own ethnic background or someone else’s.

Arturo immigrated to New York from Puerto Rico in 1891, when he was 17 years old. He carried with him letters of introduction to help him find work.

Arturo immigrated to New York from Puerto Rico in 1891, when he was 17 years old. He carried with him letters of introduction to help him find work. · Students can work in pairs to write letters of introduction for each other. Each student imagines a future job and writes a letter recommending the other student for that chosen career. What qualities and skills would be important? What would convince someone to hire the person?

“Arturo Schomburg studied the past… His mission looked to the future. ‘I am proud,’ said Schomburg, ‘to be able to do something that may mean inspiration for the youth of my race.’” He told professors to “include the practical history of the Negro race from the dawn of civilization to the present time. Then young blacks would hold their heads high and view themselves as anyone’s equal.”

Schomburg’s collection became the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library. Earlier this year, the Center was designated a national historic landmark.

· Is your school named after a person? Learn and write something about that person.· What type of building or space would you want named after you?

If these projects are initiated early in the school year, students can be encouraged to look for people whose stories are not well known in all their classes.

https://childrensbookguild.org/karen-leggett-abouraya

Published on November 13, 2017 14:00

November 6, 2017

I'm Not Taking a Bath

by Laura Gehl

In Peep and Egg’s third adventure, Peep And Egg: I’m Not Taking A Bath, Egg gets muddy playing with the pigs. Peep tries to convince Egg to take a bath…but Egg is not taking a bath. No way, no how!

After you read Peep And Egg: I’m Not Taking A Bath out loud to your class, try these activities to get your students writing.

1. Persuasive WritingPeep tries to convince Egg to take a bath by suggesting different alternatives, such as going to the river, or the duck pond, or the dog bowl. Write a letter to Egg. In your letter, try to convince Egg to try something new. It could be anything! Maybe you think Egg should go on a roller coaster. Maybe you think Egg should try your favorite video game. In your letter, give at least three reasons to convince Egg.2. Excuses, excuses!Peep gives a lot of reasons why taking a bath is nothappening—too wet, too bubbly, too slobbery!Imagine a family member is telling you to clean your room. Make up a list of excuses to show why you can’t possibly clean your room. 3. Make it fun!Peep finally convinces Egg to take a bath by making bath time seem like a lot of fun.Imagine it is your job to take out the trash or sweep the floor, but you don’t want to do it. How could you convince a brother, sister, cousin, or friend to do the job instead, by making the job seem super fun? Think of a game to make taking out the trash or sweeping the floor seem as fun as going to Disneyworld! http://www.lauragehl.com/

In Peep and Egg’s third adventure, Peep And Egg: I’m Not Taking A Bath, Egg gets muddy playing with the pigs. Peep tries to convince Egg to take a bath…but Egg is not taking a bath. No way, no how!

After you read Peep And Egg: I’m Not Taking A Bath out loud to your class, try these activities to get your students writing.

1. Persuasive WritingPeep tries to convince Egg to take a bath by suggesting different alternatives, such as going to the river, or the duck pond, or the dog bowl. Write a letter to Egg. In your letter, try to convince Egg to try something new. It could be anything! Maybe you think Egg should go on a roller coaster. Maybe you think Egg should try your favorite video game. In your letter, give at least three reasons to convince Egg.2. Excuses, excuses!Peep gives a lot of reasons why taking a bath is nothappening—too wet, too bubbly, too slobbery!Imagine a family member is telling you to clean your room. Make up a list of excuses to show why you can’t possibly clean your room. 3. Make it fun!Peep finally convinces Egg to take a bath by making bath time seem like a lot of fun.Imagine it is your job to take out the trash or sweep the floor, but you don’t want to do it. How could you convince a brother, sister, cousin, or friend to do the job instead, by making the job seem super fun? Think of a game to make taking out the trash or sweeping the floor seem as fun as going to Disneyworld! http://www.lauragehl.com/

Published on November 06, 2017 14:00

October 23, 2017

Jim the Wonder Dog--Writing About Pets

guest post by Marty Rhodes Figley

My newest book, Jim the Wonder Dog, is about a Depression Era Llewellin setter that many believed was either a genius or possessed of clairvoyant skills. This hunting dog predicted seven Kentucky Derby winners, the winners of the 1936 World Series and presidential race. He could also take direction in foreign languages (Italian, French, German, Spanish), shorthand, and Morse code—and recognized both colors and musical instruments. After a thorough examination by veterinarian scientists at the University of Missouri the mystery of Jim remained. No one could ever figure out how he did those things.

In the back of my book I have an extensive discussion of oral history. We have a much better understanding of Jim the Wonder Dog and the town where he lived because of the oral history created by the Marshall, Missouri Chamber of Commerce and the Missouri Valley College. In 1997, those two organizations conducted video interviews of people who had known Jim when they were children or young adults. Their recollections have details about Jim and Marshall, Missouri that would otherwise have been lost to time.

Classroom discussion: Discuss what an oral history is, its strengths and weaknesses.

Oral histories capture a moment in history that might have otherwise been lost.In the case of my book, these personal stories, from people who are no longer with us, about their experiences with an amazing dog they could not forget, let history come alive. Their enthusiasm and love for Jim the Wonder Dog are apparent, as is their obvious enjoyment in having an opportunity to give their honest account of their treasured memories of Jim from so long ago.

Some disadvantages of oral history are: The person who is giving the firsthand account might not have been able to observe everything that happened or his perspective might have tainted what he saw. That person also might not have made an accurate observation because of his location, the surrounding circumstances (such as darkness, rain, or smoke), or his personal circumstances (such as excitement, sleepiness, or poor eyesight). Finally, that person might not remember accurately. Memories can fade with time or be influenced by hearing other accounts of the same event.

Your students can make history come alive by creating their own oral histories by interviewing family members.

It’s important to conduct the interview in an informed manner.Ask questions one at a time. Give time for an answer before you ask the next question.Try to ask questions that can’t just be answered with a yes or no. Get more detailed responses.Be a good listener.

Here are some questions students could ask family members about their experiences with pets.

Did you have pets when you were growing up?How old were you when you got your first pet?What kind of animal was it? Where did you get it?Who named it?Who took care of the family pet?Where did your pet sleep?How did your pet show you love?Did any of your pets have special talents?What was the most interesting thing your pet did?Did you feel your pet understood you? Why?Did you have a favorite pet?If so, why was this pet your favorite?What did your favorite pet look like?Did you ever have more than one pet at the same time?If so, did they get along?

Bio: Marty Rhodes Figley is the author of several picture books including Emily and Carlo, Santa’s Underwear, Saving the Liberty Bell, andThe Schoolchildren’s Blizzard. She grew up in Missouri and now lives in Virginia with her husband and Airedale terrier. She is a graduate of Mount Holyoke College where she earned a bachelor's degree in American Studies. Besides writing for kids Marty enjoys making pies and playing the guitar. Visit Marty online at /http://www.martyrhodesfigley.com/

Bio: Marty Rhodes Figley is the author of several picture books including Emily and Carlo, Santa’s Underwear, Saving the Liberty Bell, andThe Schoolchildren’s Blizzard. She grew up in Missouri and now lives in Virginia with her husband and Airedale terrier. She is a graduate of Mount Holyoke College where she earned a bachelor's degree in American Studies. Besides writing for kids Marty enjoys making pies and playing the guitar. Visit Marty online at /http://www.martyrhodesfigley.com/

My newest book, Jim the Wonder Dog, is about a Depression Era Llewellin setter that many believed was either a genius or possessed of clairvoyant skills. This hunting dog predicted seven Kentucky Derby winners, the winners of the 1936 World Series and presidential race. He could also take direction in foreign languages (Italian, French, German, Spanish), shorthand, and Morse code—and recognized both colors and musical instruments. After a thorough examination by veterinarian scientists at the University of Missouri the mystery of Jim remained. No one could ever figure out how he did those things.

In the back of my book I have an extensive discussion of oral history. We have a much better understanding of Jim the Wonder Dog and the town where he lived because of the oral history created by the Marshall, Missouri Chamber of Commerce and the Missouri Valley College. In 1997, those two organizations conducted video interviews of people who had known Jim when they were children or young adults. Their recollections have details about Jim and Marshall, Missouri that would otherwise have been lost to time.

Classroom discussion: Discuss what an oral history is, its strengths and weaknesses.

Oral histories capture a moment in history that might have otherwise been lost.In the case of my book, these personal stories, from people who are no longer with us, about their experiences with an amazing dog they could not forget, let history come alive. Their enthusiasm and love for Jim the Wonder Dog are apparent, as is their obvious enjoyment in having an opportunity to give their honest account of their treasured memories of Jim from so long ago.

Some disadvantages of oral history are: The person who is giving the firsthand account might not have been able to observe everything that happened or his perspective might have tainted what he saw. That person also might not have made an accurate observation because of his location, the surrounding circumstances (such as darkness, rain, or smoke), or his personal circumstances (such as excitement, sleepiness, or poor eyesight). Finally, that person might not remember accurately. Memories can fade with time or be influenced by hearing other accounts of the same event.

Your students can make history come alive by creating their own oral histories by interviewing family members.

It’s important to conduct the interview in an informed manner.Ask questions one at a time. Give time for an answer before you ask the next question.Try to ask questions that can’t just be answered with a yes or no. Get more detailed responses.Be a good listener.

Here are some questions students could ask family members about their experiences with pets.

Did you have pets when you were growing up?How old were you when you got your first pet?What kind of animal was it? Where did you get it?Who named it?Who took care of the family pet?Where did your pet sleep?How did your pet show you love?Did any of your pets have special talents?What was the most interesting thing your pet did?Did you feel your pet understood you? Why?Did you have a favorite pet?If so, why was this pet your favorite?What did your favorite pet look like?Did you ever have more than one pet at the same time?If so, did they get along?

Bio: Marty Rhodes Figley is the author of several picture books including Emily and Carlo, Santa’s Underwear, Saving the Liberty Bell, andThe Schoolchildren’s Blizzard. She grew up in Missouri and now lives in Virginia with her husband and Airedale terrier. She is a graduate of Mount Holyoke College where she earned a bachelor's degree in American Studies. Besides writing for kids Marty enjoys making pies and playing the guitar. Visit Marty online at /http://www.martyrhodesfigley.com/

Bio: Marty Rhodes Figley is the author of several picture books including Emily and Carlo, Santa’s Underwear, Saving the Liberty Bell, andThe Schoolchildren’s Blizzard. She grew up in Missouri and now lives in Virginia with her husband and Airedale terrier. She is a graduate of Mount Holyoke College where she earned a bachelor's degree in American Studies. Besides writing for kids Marty enjoys making pies and playing the guitar. Visit Marty online at /http://www.martyrhodesfigley.com/

Published on October 23, 2017 14:00

Mary Quattlebaum's Blog

- Mary Quattlebaum's profile

- 22 followers

Mary Quattlebaum isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.