Mary Quattlebaum's Blog, page 4

July 9, 2018

Dressing Up for Special Occasions

by Jacqueline Jules

In my new title in the Sofia Martinez series, Sofia’s Party Shoes, Sofia is so excited about her new white shoes that she disobeys Mamá. Instead of keeping her party shoes clean and safe in their box, she wears them to her cousins’ house where they meet an unhappy accident. Sofia must face the consequences of her actions and wear the stained shoes to her friend Liliana’s quinceañera anyway. At first Sofia is grumpy, certain that she can’t have a good time. But as the party progresses, she learns that fun does not require the perfect outfit.

Read Sofia’s Party Shoes and ask students to share a time when they got something new to wear for a special occasion. How did they feel? Did the new clothes stay perfect or did something happen?

Describe the special occasion. Was it a quinceañera, a wedding, or a Bar Mitzvah? Did they look forward to attending? Or were they nervous?

Clothes can be a fun topic for young children to write about, especially dressing up for a special event. Kids might have funny stories about spills, lost ties, torn skirts, or wardrobe malfunctions.

What’s more, everyone has one item of clothing they love more than anything else in their closet. Do you remember when you got those pants or that cap? Does that T-shirt remind you of a special day with a grandparent or parent? How do you feel when you wear it? Do favorite clothes make you feel different? Why or why not?

Focusing on one special item of clothing will also give your students practice in description. What color is the dress? Can the color be compared to something else? For example, strawberry red or sky blue. Is the dress long or short? Scratchy or smooth?

When it comes to clothes, the possibilities for realistic writing are endless. Happy Writing!

www.jacquelinejules.com

Published on July 09, 2018 14:00

June 25, 2018

Pillows, Dogs, and Writing Fun

by Laura Gehl

My Pillow Keeps Moving, written by Laura Gehl and illustrated by Christopher Weyant, is the story of a lonely man who tries to buy a pillow and accidentally buys a dog—who becomes his new best friend.

After you read My Pillow Keeps Moving out loud to your students, you can use the story as a fun writing prompt. Try these suggestions for getting your students writing:

1) In this story, a man walks into a pillow store and accidentally buys a dog. Write your own story using this formula:? walks into a store to buy ? and accidentally buys ?Replace the first question mark with a character, the second question mark with an item you might buy in a store, and the third question mark with an animal.

2) The man in the story starts out with no pets and ends up with two. Do you have a pet? Do you wish you had a pet? What pet would you like to have, and why? You can even write about an imaginary creature you would love to have as a pet, like a unicorn or a dragon!

3) This book has a lot of pages without text, where the story is told only through pictures. Choose one of those pages and imagine that you need to describe what is happening to someone who cannot see the illustration. Use words to tell that part of the story.

www.lauragehl.com

Published on June 25, 2018 14:00

June 11, 2018

Cooperative Learning with Brave Like My Brother

by Jacqueline Jules

As a teacher, I was thrilled to discover Brave Like My Brother by Marc Tyler Nobleman. This slim title will make a perfect read-aloud and writing model for the upper elementary classroom. Told entirely in letters, Brave Like My Brother depicts a touching relationship between two brothers writing to each other during World War II. Joe’s letters home to younger brother Charlie share a fascinating account of an American soldier’s life abroad. The portrayal of war is neither too sugar coated nor too frightening for upper elementary students. Charlie’s letters to Joe share his struggles with a bully at home in Cleveland. The book’s large font and 100 page text should make it attractive to reluctant readers.

Letter writing is a wonderful vehicle for sharing information. After reading Brave Like My Brother, students could work in pairs, each one taking on the role of a person separated from a loved one by war or circumstance. The letters could involve research into either a historical era or geographic region. It could be an exciting cooperative project. Here are some suggestions.

Student 1: Write letters to a sister/brother/friend describing your life as you travel to a new country and build a new life.Student 2: Describe your life at home in response to these letters.

Student 1: Write letters home to a sister/brother/friend while you are at summer camp or on a vacation.Student 2: Describe your life back home in response to these letters.

Student 1: Write letters to a friend during a move to a state across the country.Student 2: Respond to the letters with information on how things are going in your friend’s old city.

Student 1: Write letters to a parent/sister/brother who is away on business, deployed, or incarcerated.Student 2: Respond to the letters, explaining your current life situation.

Student 1: Write letters to a grandparent asking what life was like for them and explaining what your life is like.Student 2: Write letters answering your grandchild’s questions.

In an age, when most people communicate by email or text rather than speaking on the phone, the ability to express ourselves by means of a letter is more important than ever. A cooperative letter writing exercise will give your students practice in both writing and essential life skills.

www.jacquelinejules.com

Published on June 11, 2018 14:00

May 21, 2018

Experimenting with Imagination

guest post by Sue Fliess

The title of my new book Mary Had A Little Lab came to me in a dream—really. So when I visit schools and talk about this book, I tell them that they can dream up any story they want—or any machine they’d like—the only limit is their imagination.

My book is about Mary, a scientist and inventor, who makes her own dreams come true. She doesn’t have friends, so she decides she needs a pet. But rather than buy one, she makes one! A sheep, of course. Once she makes a sheep, she is no longer lonely, and it soon allows her to make friends. Then her friends want sheep as well. But her Sheepinator goes haywire and starts making so many sheep that she and her new friends have to solve this new problem. The story has several problems that Mary and her friends must solve before the end. It’s like any experiment—things don’t always go right the first time. It takes many tries. Just as this book did to get it right!

My book is about Mary, a scientist and inventor, who makes her own dreams come true. She doesn’t have friends, so she decides she needs a pet. But rather than buy one, she makes one! A sheep, of course. Once she makes a sheep, she is no longer lonely, and it soon allows her to make friends. Then her friends want sheep as well. But her Sheepinator goes haywire and starts making so many sheep that she and her new friends have to solve this new problem. The story has several problems that Mary and her friends must solve before the end. It’s like any experiment—things don’t always go right the first time. It takes many tries. Just as this book did to get it right!One fun activity I do with students when I visit schools is to have them line up and recreate the Sheepinator from my book. They each have to choose what function they serve, what simple machine or movement their body must do to perform that function, and what sound it makes. They go in order, until, at last, a sheep pops out in the end—one student getting to be the sheep (I have a costume for this part, but that’s not necessary!). This gets them thinking about machine parts, how things work, and how things must work together.

Another activity is to have students create their own version of a Sheepinator. Draw a schematic on paper, then build it with arts and crafts and explain how it works.

A third, and maybe my favorite, it to ask students “If you could construct a machine to make anything you wanted, what would it be and what would it make?” This allows them total freedom. Maybe they want to create an ice-cream-o-scooper, which makes any flavor of ice cream with the push of a button. Or a Cash-o-matic that spits out money. They can draw it, explain how it works, and even create a 3-D model of it, if they like.

Let the inventions begin!

Sue Fliess("fleece") is the author of numerous children's books including A Fairy Friend, Calling All Cars, Robots, Robots Everywhere!, The Hug Book, Tons of Trucks and Shoes for Me! Sue lives with her family and a Labrador named Charlie in Northern Virginia. For more information about Sue and to check out her books and song parodies, go to http://www.suefliess.com/

Sue Fliess("fleece") is the author of numerous children's books including A Fairy Friend, Calling All Cars, Robots, Robots Everywhere!, The Hug Book, Tons of Trucks and Shoes for Me! Sue lives with her family and a Labrador named Charlie in Northern Virginia. For more information about Sue and to check out her books and song parodies, go to http://www.suefliess.com/

Published on May 21, 2018 14:00

May 7, 2018

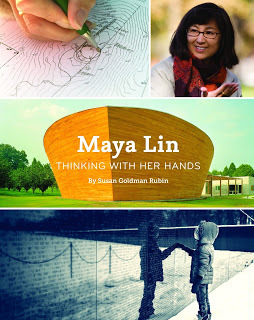

“Thinking with her hands”

by Karen Leggett Abouraya

Maya Lin has built monuments in clay, granite, water, earth, glass and wood. Her most famous monument is the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, an opportunity she won in a contest she entered anonymously as a college student. It was controversial from the beginning. Critics wondered why a person of Asian heritage should design a monument to veterans of a war fought against Asians. Others criticized what appeared to them as a black scar in the earth. But now this monument in Washington, D.C., is visited by more than three million people every year.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial/Creative Commons photoSusan Goldman Rubin’s new and highly acclaimed biography of Maya Lin – Maya Lin: thinking with her hands - includes photos of the many more monuments and sculptures she has designed, along with her struggles about whether and how to design each one.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial/Creative Commons photoSusan Goldman Rubin’s new and highly acclaimed biography of Maya Lin – Maya Lin: thinking with her hands - includes photos of the many more monuments and sculptures she has designed, along with her struggles about whether and how to design each one.

“I try to understand the ‘why’ of a project before it’s a ‘what.’”

“I try to understand the ‘why’ of a project before it’s a ‘what.’”

She used the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama, to “give people an understanding of what that time period was about.” She literally sculpted the earth to create a grassy Wave Field at the University of Michigan’s aerospace engineering building. She redesigned an old barn for a retreat center in Tennessee for the Children’s Defense Fund.

Not only is Maya Lin: Thinking with her hands a thought-provoking story of how an artist works, it can spur conversations and writing as well. It could be a perfect way to open a discussion of national and local monuments – including the many that are controversial right now - but you could also have students :

· Write about a monument or statue in your town. What does it mean to you? Why is it important for that statue to be in your town?· Do you think there are other monuments that could be added or removed from your town? Write a persuasive essay explaining your reasons.· If your school is named for a person, what sort of monument would you create to honor that person? This could be a class project, especially for younger children. (My own children’s elementary school in Montgomery County, Maryland, was always known just as “Barnsley.” Turns out it was the first Montgomery County school named for a woman. Lucy V. Barnsley not only taught for 35 years, but also donated books to start the first library in Rockville and started the Retired Teachers Association in the county.)· Design a monument to any person or event that is important to you and write an artist’s statement about your monument. Maya Lin’s essay about her Vietnam Veterans Memorial competition entry is included in the book, but may also be read here.

Maya Lin expects her last commission to be a project called “What is Missing?” at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in Ithaca, New York. This ecological history of the planet invites scientists, conservationists and everyone to find ways to “learn enough from the past to rethink a different and better future.” And that can spark many many more writing ideas.

https://childrensbookguild.org/index.php/karen-leggett-abouraya

Maya Lin has built monuments in clay, granite, water, earth, glass and wood. Her most famous monument is the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, an opportunity she won in a contest she entered anonymously as a college student. It was controversial from the beginning. Critics wondered why a person of Asian heritage should design a monument to veterans of a war fought against Asians. Others criticized what appeared to them as a black scar in the earth. But now this monument in Washington, D.C., is visited by more than three million people every year.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial/Creative Commons photoSusan Goldman Rubin’s new and highly acclaimed biography of Maya Lin – Maya Lin: thinking with her hands - includes photos of the many more monuments and sculptures she has designed, along with her struggles about whether and how to design each one.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial/Creative Commons photoSusan Goldman Rubin’s new and highly acclaimed biography of Maya Lin – Maya Lin: thinking with her hands - includes photos of the many more monuments and sculptures she has designed, along with her struggles about whether and how to design each one.  “I try to understand the ‘why’ of a project before it’s a ‘what.’”

“I try to understand the ‘why’ of a project before it’s a ‘what.’” She used the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama, to “give people an understanding of what that time period was about.” She literally sculpted the earth to create a grassy Wave Field at the University of Michigan’s aerospace engineering building. She redesigned an old barn for a retreat center in Tennessee for the Children’s Defense Fund.

Not only is Maya Lin: Thinking with her hands a thought-provoking story of how an artist works, it can spur conversations and writing as well. It could be a perfect way to open a discussion of national and local monuments – including the many that are controversial right now - but you could also have students :

· Write about a monument or statue in your town. What does it mean to you? Why is it important for that statue to be in your town?· Do you think there are other monuments that could be added or removed from your town? Write a persuasive essay explaining your reasons.· If your school is named for a person, what sort of monument would you create to honor that person? This could be a class project, especially for younger children. (My own children’s elementary school in Montgomery County, Maryland, was always known just as “Barnsley.” Turns out it was the first Montgomery County school named for a woman. Lucy V. Barnsley not only taught for 35 years, but also donated books to start the first library in Rockville and started the Retired Teachers Association in the county.)· Design a monument to any person or event that is important to you and write an artist’s statement about your monument. Maya Lin’s essay about her Vietnam Veterans Memorial competition entry is included in the book, but may also be read here.

Maya Lin expects her last commission to be a project called “What is Missing?” at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in Ithaca, New York. This ecological history of the planet invites scientists, conservationists and everyone to find ways to “learn enough from the past to rethink a different and better future.” And that can spark many many more writing ideas.

https://childrensbookguild.org/index.php/karen-leggett-abouraya

Published on May 07, 2018 14:00

April 22, 2018

Taking Care of the Earth

guest post by Madelyn Rosenberg

Both Earth Day and National Poetry Month fall during April, so it’s a good time to introduce you to Take Care, a rhyming book about taking care of the earth and each other.

I wrote Take Care after watching a series of gut-wrenching events unfold in the news. This particular series of events culminated in the nightclub shooting in Orlando. How can we keep doing this to each other?I thought – and have thought, again, many times since. I have similar thoughts when I see people abusing the planet – when someone throws a cigarette butt out a car window or when they find a whale on a beach in Spain with his stomachfull of plastic.

I react with rage. And sadness. And I try to reassure myself that we can learn to take care of each other and the planet and make things better. Poetry, whether we’re writing it or reading it, can be burn or balm. My book is meant to be a balm, though it’s fueled by burn. It begins:

Take care of the world, of the mountains and treesTend to the world, all the bumbles and beesColor the world, with greens and with bluesHeal up the world with the words that you choose

Following are a few related prompts:

Emotion poemsWhat makes you angry? What makes you sad? What makes you happy and what makes you heal? All poems convey emotion, and for this writing prompt, we’re going to come at it full throttle. The lesson I try to always teach my kids when it comes to writing is that specifics are important. So urge your class, when they’re writing about a particular emotion, to think really hard about the things that make them feel the way they do. Does their emotion have a color? A temperature? A season? Is it tied to a specific event, like a fight with a friend or the loss of a stuffed animal? (Was anyone else riveted by the search for the rabbit lost on the London Underground?) There are no real rules for this one, but for students who thrive with rules, you can tell them the poem has to be the same number of lines as letters in the type of emotion they’re feeling – or a multiple of that if it’s a short one. Challenge: Can you convey the emotion without mentioning it by name?

A letter to the worldHave the class write a letter to the planet. Maybe it’s an apology note. Maybe it’s a thank you note for a dandelion or a dimpled strawberry or the color green. Again, it’s always great when you can get kids to focus on something specific. Want to get them in the right mood? ? Consider a nature walk around the school for inspiration. Prose or poetry for this one, your pick.

A letter to the worldHave the class write a letter to the planet. Maybe it’s an apology note. Maybe it’s a thank you note for a dandelion or a dimpled strawberry or the color green. Again, it’s always great when you can get kids to focus on something specific. Want to get them in the right mood? ? Consider a nature walk around the school for inspiration. Prose or poetry for this one, your pick.A take-care treeIngredients:A tree branch (a fallen one, please =)A hole punchString or yarn“Leaves” cut from recycled paper. It’s fine if there is printing on one side, as long as the other side is blank. Multiple colors help.A flower potRocks or newspapers

Place the branch in the flowerpot and use rocks or wadded up newspapers to hold it in place. Have students write their ideas for taking care of the world on the paper leaves. Punch a hole in each leaf and attach it to your branch with the string. Use as a reminder and a classroom decoration for Earth Day, Arbor Day, Tu B’shevat or spring.

Place the branch in the flowerpot and use rocks or wadded up newspapers to hold it in place. Have students write their ideas for taking care of the world on the paper leaves. Punch a hole in each leaf and attach it to your branch with the string. Use as a reminder and a classroom decoration for Earth Day, Arbor Day, Tu B’shevat or spring. ADAPT IT: If your students do the letters-to-the-world prompt, excerpts on tree leaves also make a nice classroom display.

BIO: As a journalist, Madelyn Rosenberg spent many years writing about colorful, real-life characters. Now she makes up characters of her own. The author of award-winning books for young people, she lives with her family in Arlington, Va. For more information, visit her web site at madelynrosenberg.com or follow her on twitter at @madrosenberg. And if you try this exercise in your classroom, she’d love to see the results!

Published on April 22, 2018 06:00

April 9, 2018

HIC! HIC! Writing about the Hiccups

by Jacqueline Jules

Hiccups are funny! They happen to everyone! An experience everyone can relate to makes a great writing prompt for a personal narrative. It can also give your students an opportunity to write humor since hiccups often create a funny situation.

In my new book, Hector’s Hiccups, Sofia and her cousin, Hector plan to attend a movie with Abuela. They are all ready to go when they realize Hector has the hiccups. Abuela tries to cure Hector with a lemon and other remedies. Sofia tries to help by holding her breath with Hector. HIC! HIC! Now Sofia has the hiccups, too. Abuela suggests a change of plans and soon they are all dancing in the kitchen. Who says the hiccups can’t be fun?

After reading Hector’s Hiccups to your class, ask your students to describe a day when they experienced the hiccups. Ask them to consider the following questions to expand their narrative.

1. Describe the time of day and what you were doing when the hiccups started.2. Did you change your plans or keep on with whatever you were doing? 3. Did you get the hiccups in a place where you were supposed to be quiet?4. How long did your hiccups last?5. Were you embarrassed? Frustrated? Or did you laugh? 6. Did others try to help you?7. What is your favorite cure for hiccups?8. Did you learn something from the experience?

Happy Writing!

www.jacquelinejules.com

Hiccups are funny! They happen to everyone! An experience everyone can relate to makes a great writing prompt for a personal narrative. It can also give your students an opportunity to write humor since hiccups often create a funny situation.

In my new book, Hector’s Hiccups, Sofia and her cousin, Hector plan to attend a movie with Abuela. They are all ready to go when they realize Hector has the hiccups. Abuela tries to cure Hector with a lemon and other remedies. Sofia tries to help by holding her breath with Hector. HIC! HIC! Now Sofia has the hiccups, too. Abuela suggests a change of plans and soon they are all dancing in the kitchen. Who says the hiccups can’t be fun?

After reading Hector’s Hiccups to your class, ask your students to describe a day when they experienced the hiccups. Ask them to consider the following questions to expand their narrative.

1. Describe the time of day and what you were doing when the hiccups started.2. Did you change your plans or keep on with whatever you were doing? 3. Did you get the hiccups in a place where you were supposed to be quiet?4. How long did your hiccups last?5. Were you embarrassed? Frustrated? Or did you laugh? 6. Did others try to help you?7. What is your favorite cure for hiccups?8. Did you learn something from the experience?

Happy Writing!

www.jacquelinejules.com

Published on April 09, 2018 14:00

March 18, 2018

Animals As Characters/Subjects: Pushing Against Gender Typing

by Mary Quattlebaum

Starting March 1st, we’re celebrating Women’s History Month with 31 days of posts focused on improving the climate for social and gender equality in the children’s and teens’ community/industry. Join in the conversation on Twitter at #kidlitwomen or on Facebook at https:www//www.facebook.com/kidlitwomen (which includes all the posts this month).

Starting March 1st, we’re celebrating Women’s History Month with 31 days of posts focused on improving the climate for social and gender equality in the children’s and teens’ community/industry. Join in the conversation on Twitter at #kidlitwomen or on Facebook at https:www//www.facebook.com/kidlitwomen (which includes all the posts this month).

Misty of Chincoteagueby Marguerite Henry. Black Beauty by Anna Sewell. I read these novels multiple times as a kid. I adored the fierce mare, Phantom, who cared for her domesticated foal until Misty could live on her own, and then returned to the wild. I cried over the trials of sensitive, observant Black Beauty, the male horse in the 19th century bestseller that galvanized the movement for more humane treatment of animals.

Lassie Come-Homeby Eric Knight. The Incredible Journeyby Sheila Burnford. The Hundred and One Dalmatians by Dodie Smith. No matter their sex, the animal characters in these books were, by turns, loyal, cooperative, intelligent, kind, sturdy, afraid, vulnerable, and angry. They had personality strengths and flaws. They fought, strategized, searched for food, and cared for their young. They persisted. They triumphed, in different ways. They were the heroes of their stories.

Growing up in the 1960s and ‘70s, I remember very, very few books with strong human girl and gentle human boy characters. I didn’t even realize what I was searching for until, as an adult, I examined my favorite books more closely. Yes, I had been a country kid, a lover of animals and the natural world, but even deeper than that, I think I was hoping for depictions in books that better reflected some of the change I was glimpsing in the wider world. The realistic, slightly anthropomorphized critter-characters in these novels pushed boundaries. They brought nuance to, and even subverted the traditional gender-assigned roles and traits of the times. (Interestingly, for picture books, almost the opposite is true. In her research, children’s author/scholar Jennifer Mann discovered that anthropomorphized animals—especially parents, teachers and other adults--tended to remain gender typed, especially in terms of clothing.)

In the blog post that opened this #kidlitwomen discussion, Shannon Hale asked us to deeply consider how we as creators and as teachers/librarians/parents present books to young people. Do we or others unconsciously label or have expectations of a book as being “for girls” or of a particular author as appealing primarily to boys? How might we work against this? In their posts, Susan Van Metre, Meg Frazer Blakemore, and Elizabeth Dulemba further explore ideas and possibilities around re-shaping the cultural narrative.

As a writer of nonfiction about/fiction with animal characters, I’ve tried to be alert to my own shortcomings, blind spots, and expectations (with full awareness of how much I still need to learn/unlearn)—and those of the larger society. And I want to present my work—and that of others—in a way that encourages kids to think more deeply and critically about these issues too.

For a nonfiction chapter book about Hero Dogs, I wanted to broaden the narrative about heroic animals beyond the usual stories about military/law-enforcement dogs and the single act of bravery, so I included true stories about a female detective dog who has found hundreds of lost pets; two female “nurse” dogs at a wildlife sanctuary; and a male Dalmatian who is a fire-safety educator. At schools, I ask kids to think about the term “hero” and what it means to them—and we talk about examples of heroes in history and their lives who may exemplify a range of heroic traits.

Mighty Mole and Super Soil depicts the real-life superhero of the animal kingdom, a female mole with super strength, super speed, and a super appetite. Mighty Mole is like Wonder Woman, I tell kids. Only she has fur and claws and teeny-tiny eyes (and no bustier, I might add, but that’s the subject for another post).

Many kids love reading and talking about animals. Since #kidlit women encourages solution-based discussions, I want to ask: What’s your favorite book about animals that works against gender typing? And/or your favorite book about/with animal characters by a woman?

My choice: Hello, Universe by Erin Entrada Kelly. So much love for this year’s Newbery Medal winner! I especially admire the characterizations of the gentle boy and his beloved guinea pig and the fierce Nature-loving deaf girl who helps to rescue them.

www.maryquattlebaum.com

Starting March 1st, we’re celebrating Women’s History Month with 31 days of posts focused on improving the climate for social and gender equality in the children’s and teens’ community/industry. Join in the conversation on Twitter at #kidlitwomen or on Facebook at https:www//www.facebook.com/kidlitwomen (which includes all the posts this month).

Starting March 1st, we’re celebrating Women’s History Month with 31 days of posts focused on improving the climate for social and gender equality in the children’s and teens’ community/industry. Join in the conversation on Twitter at #kidlitwomen or on Facebook at https:www//www.facebook.com/kidlitwomen (which includes all the posts this month).Misty of Chincoteagueby Marguerite Henry. Black Beauty by Anna Sewell. I read these novels multiple times as a kid. I adored the fierce mare, Phantom, who cared for her domesticated foal until Misty could live on her own, and then returned to the wild. I cried over the trials of sensitive, observant Black Beauty, the male horse in the 19th century bestseller that galvanized the movement for more humane treatment of animals.

Lassie Come-Homeby Eric Knight. The Incredible Journeyby Sheila Burnford. The Hundred and One Dalmatians by Dodie Smith. No matter their sex, the animal characters in these books were, by turns, loyal, cooperative, intelligent, kind, sturdy, afraid, vulnerable, and angry. They had personality strengths and flaws. They fought, strategized, searched for food, and cared for their young. They persisted. They triumphed, in different ways. They were the heroes of their stories.

Growing up in the 1960s and ‘70s, I remember very, very few books with strong human girl and gentle human boy characters. I didn’t even realize what I was searching for until, as an adult, I examined my favorite books more closely. Yes, I had been a country kid, a lover of animals and the natural world, but even deeper than that, I think I was hoping for depictions in books that better reflected some of the change I was glimpsing in the wider world. The realistic, slightly anthropomorphized critter-characters in these novels pushed boundaries. They brought nuance to, and even subverted the traditional gender-assigned roles and traits of the times. (Interestingly, for picture books, almost the opposite is true. In her research, children’s author/scholar Jennifer Mann discovered that anthropomorphized animals—especially parents, teachers and other adults--tended to remain gender typed, especially in terms of clothing.)

In the blog post that opened this #kidlitwomen discussion, Shannon Hale asked us to deeply consider how we as creators and as teachers/librarians/parents present books to young people. Do we or others unconsciously label or have expectations of a book as being “for girls” or of a particular author as appealing primarily to boys? How might we work against this? In their posts, Susan Van Metre, Meg Frazer Blakemore, and Elizabeth Dulemba further explore ideas and possibilities around re-shaping the cultural narrative.

As a writer of nonfiction about/fiction with animal characters, I’ve tried to be alert to my own shortcomings, blind spots, and expectations (with full awareness of how much I still need to learn/unlearn)—and those of the larger society. And I want to present my work—and that of others—in a way that encourages kids to think more deeply and critically about these issues too.

For a nonfiction chapter book about Hero Dogs, I wanted to broaden the narrative about heroic animals beyond the usual stories about military/law-enforcement dogs and the single act of bravery, so I included true stories about a female detective dog who has found hundreds of lost pets; two female “nurse” dogs at a wildlife sanctuary; and a male Dalmatian who is a fire-safety educator. At schools, I ask kids to think about the term “hero” and what it means to them—and we talk about examples of heroes in history and their lives who may exemplify a range of heroic traits.

Mighty Mole and Super Soil depicts the real-life superhero of the animal kingdom, a female mole with super strength, super speed, and a super appetite. Mighty Mole is like Wonder Woman, I tell kids. Only she has fur and claws and teeny-tiny eyes (and no bustier, I might add, but that’s the subject for another post).

Many kids love reading and talking about animals. Since #kidlit women encourages solution-based discussions, I want to ask: What’s your favorite book about animals that works against gender typing? And/or your favorite book about/with animal characters by a woman?

My choice: Hello, Universe by Erin Entrada Kelly. So much love for this year’s Newbery Medal winner! I especially admire the characterizations of the gentle boy and his beloved guinea pig and the fierce Nature-loving deaf girl who helps to rescue them.

www.maryquattlebaum.com

Published on March 18, 2018 16:31

Animals Characters/Subjects: Pushing Against Gender Typing

by Mary Quattlebaum

Starting March 1st, we’re celebrating Women’s History Month with 31 days of posts focused on improving the climate for social and gender equality in the children’s and teens’ community/industry.

Join in the conversation on Twitter at #kidlitwomen or on Facebook at https:www//www.facebook.com/kidlitwomen (which includes all the posts this month).

Misty of Chincoteagueby Marguerite Henry. Black Beauty by Anna Sewell. I read these novels multiple times as a kid. I adored the fierce mare, Phantom, who cared for her domesticated foal until Misty could live on her own, and then returned to the wild. I cried over the trials of sensitive, observant Black Beauty, the male horse in the 19th century bestseller that galvanized the movement for more humane treatment of animals.

Lassie Come-Homeby Eric Knight. The Incredible Journeyby Sheila Burnford. The Hundred and One Dalmatians by Dodie Smith. No matter their sex, the animal characters in these books were, by turns, loyal, cooperative, intelligent, kind, sturdy, afraid, vulnerable, and angry. They had personality strengths and flaws. They fought, strategized, searched for food, and cared for their young. They persisted. They triumphed, in different ways. They were the heroes of their stories.

Growing up in the 1960s and ‘70s, I remember very, very few books with strong human girl and gentle human boy characters. I didn’t even realize what I was searching for until, as an adult, I examined my favorite books more closely. Yes, I had been a country kid, a lover of animals and the natural world, but even deeper than that, I think I was hoping for depictions in books that better reflected some of the change I was glimpsing in the wider world. The realistic, slightly anthropomorphized critter-characters in these novels pushed boundaries. They brought nuance to, and even subverted the traditional gender-assigned roles and traits of the times. (Interestingly, for picture books, almost the opposite is true. In her research, children’s author/scholar Jennifer Mann discovered that anthropomorphized animals—especially parents, teachers and other adults--tended to remain gender typed, especially in terms of clothing.)

In the blog post that opened this #kidlitwomen discussion, Shannon Hale asked us to deeply consider how we as creators and as teachers/librarians/parents present books to young people. Do we or others unconsciously label or have expectations of a book as being “for girls” or of a particular author as appealing primarily to boys? How might we work against this? In their posts, Susan Van Metre, Meg Frazer Blakemore, and Elizabeth Dulemba further explore ideas and possibilities around re-shaping the cultural narrative.

As a writer of nonfiction about/fiction with animal characters, I’ve tried to be alert to my own shortcomings, blind spots, and expectations (with full awareness of how much I still need to learn/unlearn)—and those of the larger society. And I want to present my work—and that of others—in a way that encourages kids to think more deeply and critically about these issues too.

For a nonfiction chapter book about Hero Dogs, I wanted to broaden the narrative about heroic animals beyond the usual stories about military/law-enforcement dogs and the single act of bravery, so I included true stories about a female detective dog who has found hundreds of lost pets; two female “nurse” dogs at a wildlife sanctuary; and a male Dalmatian who is a fire-safety educator. At schools, I ask kids to think about the term “hero” and what it means to them—and we talk about examples of heroes in history and their lives who may exemplify a range of heroic traits.

Mighty Mole and Super Soil depicts the real-life superhero of the animal kingdom, a female mole with super strength, super speed, and a super appetite. Mighty Mole is like Wonder Woman, I tell kids. Only she has fur and claws and teeny-tiny eyes (and no bustier, I might add, but that’s the subject for another post).

Many kids love reading and talking about animals. Since #kidlit women encourages solution-based discussions, I want to ask: What’s your favorite book about animals that works against gender typing? And/or your favorite book about/with animal characters by a woman.

My choice: Hello, Universe by Erin Entrada Kelly. So much love for this year’s Newbery Medal winner! I especially admire the characterizations of the gentle boy and his beloved guinea pig and the fierce Nature-loving deaf girl who helps to rescue them.

www.maryquattlebaum.com

Published on March 18, 2018 16:31

March 7, 2018

Young People Making a Difference

by Karen Leggett Abouraya

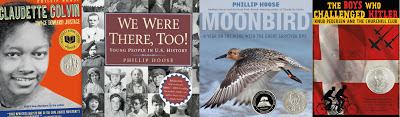

Children’s Book Guild 2018 Nonfiction Award Winner Phillip Hoose has always been intrigued by young people who make a difference in their world. They are the subject of most of his books, especially after Sarah Rosen - a teenager in South Bend, Indiana - asked him, “We’re not taught about young people who have made a difference. Studying history almost makes you feel like you’re not a real person.” Hoose decided he would be the author to find and share the stories of real young people making a difference.

Hoose brings young leaders to life, including Sarah Rosen in It’s Our World, Too! along with many more in We Were There, Too! Young People in U.S. History. With the meticulous research that characterizes all of his books, Hoose has identified youngsters who sailed with Christopher Columbus right up to those who have been active in the 20th and 21stcenturies: Olaudah Equiano, who was kidnapped into slavery in Benin, Africa, in 1756; teens Billy Bates and Dick King who escaped from the dreaded Andersonville prison during the Civil War; fourteen-year-old Susie King Taylor, a former slave who had learned to read and shared her skills with countless illiterate children and adults; eight-year-old Margaret Davidson who worked in small ways to counter the anti-German sentiments in her Iowa town during World War II.

Ideas for writing and action pop from every page of Hoose’s books.· Write a journal entry for any one of the young people he describes.o Imagine being twelve-year-old Diego Bermúdez. Why did you leave your home? What work did you do on Christopher Columbus’ ship? What was boring? What was exciting? Diego returned to Spain and did not come to the New World again. Why not? His brother Juan did sail across the ocean and the Bermuda Islands were later named for him. These journals also provide an opportunity to discuss the difference between historical fiction – journals that your students would write – and nonfiction, based on primary sources and verifiable facts.

· What would you like to change in your school or community? How could you begin to make that change? This could be a class discussion and project. o Write a plan to lobby or work for the change you desire.o Hoose’s book It’s Our World, Too! includes a “A Handbook for Young Activists” with resources and tools for change. The website Youth Activism Project includes many other ideas and examples. The Co-President of the Youth Activism Project, Anika Manzour, helped start School Girls Unite as a middle school student in Kensington, Maryland.

Phillip Hoose says the young people in his books “deserve attention not simply because they are ‘real people’ close to your age. They are important because through their sweat, bravery, luck, talent, imagination and sacrifice – sometimes of their lives – they helped shape our nation.”

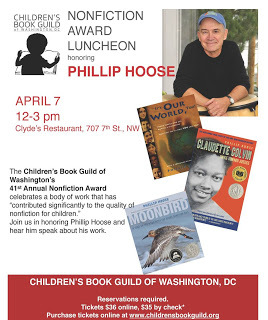

Librarians, teachers and students are all invited to hear Phillip Hoose speak at the Children’s Book Guild Nonfiction Award Celebrationon April 7 in Washington, D.C. More details and reservations at www.childrensbookguild.org.

www.childrensbookguild.org

Published on March 07, 2018 17:30

Mary Quattlebaum's Blog

- Mary Quattlebaum's profile

- 22 followers

Mary Quattlebaum isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.