Mary Quattlebaum's Blog, page 12

June 20, 2016

Writing Excellence with EXCELLENT ED

by Laura Gehl

Excellent Ed, by Stacy McAnulty, tells the story of the Ellis family, where all of the children are excellent—at all kinds of things! Poor Ed, the family dog, feels a bit left out. Ed wants to be excellent too.

In the classroom, Excellent Ed makes a great writing prompt. Here are a few ideas for using the book in your classroom.

1. Ask students to make a list of their own excellent qualities—and remind them to think outside of the box. Some students may be excellent at math, or gymnastics, or soccer. But they can think of more unusual excellent traits as well. Perhaps one student is excellent at putting off cleaning her room or making realistic fake vomit sounds whenever she sees chopped liver. Perhaps another student is excellent at tying his shoes in knots so tight that his dad can’t get them out.

2. Ask students to make a list of another person’s excellent qualities. This could be a parent, friend, or teacher, for example.

3. Just like Ed the family dog, every kid (and adult) sometimes feels…less than excellent. Ask your students to make a list of excellent qualities they WISH they had. Do they wish they could jump higher than the Empire State Building? Turn Brussels sprouts into chocolate? See through walls? Or, maybe students wish they could make sad a friend feel better, shoot a goal at the next hockey game, or learn how to ride a bike. You could even encourage students to make two wish lists—one of realistic qualities, and one of crazy, over-the-top, not-gonna-happen-but-fun-to-think-about qualities.

4. Make an “Excellent Sheet” for each student in the room, with the student’s name at the top. Ask students to write on each other’s Excellent Sheets, writing at least one excellent quality of the student on his or her sheet. When students get to take home their Excellent Sheets, they will have a concrete reminder of their own excellent qualities, as seen through the eyes of their peers.

Excellent Ed is a wonderful book for reminding students how excellent they all are, in their own unique ways!

http://www.lauragehl.com/

Excellent Ed, by Stacy McAnulty, tells the story of the Ellis family, where all of the children are excellent—at all kinds of things! Poor Ed, the family dog, feels a bit left out. Ed wants to be excellent too.

In the classroom, Excellent Ed makes a great writing prompt. Here are a few ideas for using the book in your classroom.

1. Ask students to make a list of their own excellent qualities—and remind them to think outside of the box. Some students may be excellent at math, or gymnastics, or soccer. But they can think of more unusual excellent traits as well. Perhaps one student is excellent at putting off cleaning her room or making realistic fake vomit sounds whenever she sees chopped liver. Perhaps another student is excellent at tying his shoes in knots so tight that his dad can’t get them out.

2. Ask students to make a list of another person’s excellent qualities. This could be a parent, friend, or teacher, for example.

3. Just like Ed the family dog, every kid (and adult) sometimes feels…less than excellent. Ask your students to make a list of excellent qualities they WISH they had. Do they wish they could jump higher than the Empire State Building? Turn Brussels sprouts into chocolate? See through walls? Or, maybe students wish they could make sad a friend feel better, shoot a goal at the next hockey game, or learn how to ride a bike. You could even encourage students to make two wish lists—one of realistic qualities, and one of crazy, over-the-top, not-gonna-happen-but-fun-to-think-about qualities.

4. Make an “Excellent Sheet” for each student in the room, with the student’s name at the top. Ask students to write on each other’s Excellent Sheets, writing at least one excellent quality of the student on his or her sheet. When students get to take home their Excellent Sheets, they will have a concrete reminder of their own excellent qualities, as seen through the eyes of their peers.

Excellent Ed is a wonderful book for reminding students how excellent they all are, in their own unique ways!

http://www.lauragehl.com/

Published on June 20, 2016 14:00

June 13, 2016

Writing Instructions with A Fairy Friend

Guest post by Sue Fliess

To believe in magic fills the heart and mind with wonder. As a child, I always imagined I wasn’t alone and believed that some kind of magical creatures must exist. Were there aliens? Beings that we couldn’t see, but lived among us? So tiny we didn’t know they were there, or so big that our Earth could fit on their fingernail? I thought anything was possible.

In my newest book, A Fairy Friend , illustrated by Claire Keane and published by Macmillan, I write about magical, mystical fairies; how they live among us, and how one only needs to know where to look and what to do to attract one.

The story invites the reader to join that miniature dream world by giving detailed instructions on how to do so.

Want to have one come to you? Here is what you need to do…Build a house of twigs and blooms, Decorate her fairy rooms—Walls of blossoms, cotton floor, Sparrow feather for her door.

This is a great opportunity for you to have your class write their own set of instructions (explaining to them that they are writing from a second person point of view), talking directly to their reader.

Have students choose something they are passionate about—sports, dancing, dogs, playing an instrument, building, cooking, etc. The first few sentences can be description about that topic or thing.

Friendly fairies soar the skies,Ride the backs of dragonflies.Wings of fairies shimmer, spark, Twinkle, glimmer in the dark.

The next part can be where they write out instructions on, for example, how to score a goal in soccer, how to teach a dog to sit, how to pirouette, construct a fort, or even how to make a peanut butter sandwich.

Encourage them to be as detailed as possible, and to assume that the reader has never tried this particular thing before. If possible, as with the dance move, have the other students follow the instructions of their peers.

They can wrap it up by writing about the results of following the actions – how it feels to score a goal, what it’s like to perform a ballet recital, how yummy a peanut butter sandwich is, and so on.

Many reluctant writers find writing instructions lots of fun. And it is a welcome change for students to be able to instruct someone else on what do to, instead of always being told what do to.

BIO: Sue Fliess ("fleece") is the author of numerous children's books including A Fairy Friend, Calling All Cars, Robots, Robots Everywhere!, The Hug Book, Tons of Trucks and Shoes for Me! Her background is in copywriting, PR, and marketing, and her articles have appeared in O the Oprah Magazine, Huffington Post, Writer's Digest, Education.com, and more. Her Oprah article was included in the anthology, O's Little Book of Happiness. Fliess has also written stories for The Walt Disney Company. Her picture books have received honors from the Society of Children's Books Writers and Illustrators, have been used in school curriculums, museum educational programs, and have even been translated into French. She's a member of SCBWI and The Children's Book Guild of DC. Sue lives with her family and a Labrador named Charlie in Northern Virginia. Visit her at www.suefliess.com.

BIO: Sue Fliess ("fleece") is the author of numerous children's books including A Fairy Friend, Calling All Cars, Robots, Robots Everywhere!, The Hug Book, Tons of Trucks and Shoes for Me! Her background is in copywriting, PR, and marketing, and her articles have appeared in O the Oprah Magazine, Huffington Post, Writer's Digest, Education.com, and more. Her Oprah article was included in the anthology, O's Little Book of Happiness. Fliess has also written stories for The Walt Disney Company. Her picture books have received honors from the Society of Children's Books Writers and Illustrators, have been used in school curriculums, museum educational programs, and have even been translated into French. She's a member of SCBWI and The Children's Book Guild of DC. Sue lives with her family and a Labrador named Charlie in Northern Virginia. Visit her at www.suefliess.com.

Published on June 13, 2016 14:00

June 6, 2016

Summer Travel Sketch Journal Kit

by Joan Waites

The end of the year is already here or coming soon for most schools. How did another year zip by so quickly?

Whether you are spending summer days close to home, at the park, local pool, or traveling for a fun vacation, keeping a travel sketch and writing journal kit handy is a great way to keep the creativity flowing for kids of all ages. Recording what you see or experience in pictures and words will keep those memories alive for years to come.

Have your children take as little as 15 minutes a day to observe something around them. An everyday object in the home, a bird or bug in the backyard, or a sandy beach with colorful umbrellas can be recorded in a quick sketch along with some descriptive words or sentences. At the end of the summer, you will have a visual diary to remember small details that might otherwise be forgotten.

A travel kit can be something as simple as a small notebook, pencil and some crayons contained in a zippered pouch. A pencil or cosmetic case makes a great take-along bag to bring anywhere you go. If you’d like to add additional items to your travel bag, here are a few things I recommend:

*Small sketch journal with heavyweight paper that will hold up to wet media.

*Drawing pencil and eraser (a mechanical pencil works well and doesn’t require sharpening).

*Permanent black fine tipped ink pen such as a Sharpie or Micron pen for sketching and writing.

*Small set of watercolors and or some watercolor pencils or watercolor crayons.

*Water brush (a self-contained brush with a watercontainer in the handle).

Wishing you all a wonderful start to the summer!

www.joanwaites.com

The end of the year is already here or coming soon for most schools. How did another year zip by so quickly?

Whether you are spending summer days close to home, at the park, local pool, or traveling for a fun vacation, keeping a travel sketch and writing journal kit handy is a great way to keep the creativity flowing for kids of all ages. Recording what you see or experience in pictures and words will keep those memories alive for years to come.

Have your children take as little as 15 minutes a day to observe something around them. An everyday object in the home, a bird or bug in the backyard, or a sandy beach with colorful umbrellas can be recorded in a quick sketch along with some descriptive words or sentences. At the end of the summer, you will have a visual diary to remember small details that might otherwise be forgotten.

A travel kit can be something as simple as a small notebook, pencil and some crayons contained in a zippered pouch. A pencil or cosmetic case makes a great take-along bag to bring anywhere you go. If you’d like to add additional items to your travel bag, here are a few things I recommend:

*Small sketch journal with heavyweight paper that will hold up to wet media.

*Drawing pencil and eraser (a mechanical pencil works well and doesn’t require sharpening).

*Permanent black fine tipped ink pen such as a Sharpie or Micron pen for sketching and writing.

*Small set of watercolors and or some watercolor pencils or watercolor crayons.

*Water brush (a self-contained brush with a watercontainer in the handle).

Wishing you all a wonderful start to the summer!

www.joanwaites.com

Published on June 06, 2016 14:00

May 30, 2016

Writing Connections with Shawn Stout

by Mary Quattlebaum

Family can be inspiring, as Shawn Stout discovered when writing her eighth novel

A Tiny Piece of Sky

. In an interview for KidsPost/WashingtonPost, Stout talked about the prejudice her German-American grandfather dealt with right before World War II. Shawn fictionalized her family’s experiences, but she asked her mother and aunts many questions about their childhood. She wanted to convey a child’s perspective of the townspeople’s boycott of her grandfather’s restaurant and of their (false) perception of him as a German spy.

Family can be inspiring, as Shawn Stout discovered when writing her eighth novel

A Tiny Piece of Sky

. In an interview for KidsPost/WashingtonPost, Stout talked about the prejudice her German-American grandfather dealt with right before World War II. Shawn fictionalized her family’s experiences, but she asked her mother and aunts many questions about their childhood. She wanted to convey a child’s perspective of the townspeople’s boycott of her grandfather’s restaurant and of their (false) perception of him as a German spy.

Below are writing lessons for the classroom or for individual writers ages 8 and up. Stout’s website http://shawnkstout.com/ includes a teachers’ guide.

RETURN TO THE PAST: As the youngest in her family, 10-year-old Frankie Baum feels she lacks the respect and privileges accorded her two older siblings. She is determined to prove that her father is no spy. As she gets to know some of the African American staff in her father’s restaurant, Frankie also becomes more aware of the injustices suffered by blacks in the segregated Maryland town. She speaks frequently about her favorite book “The Wizard of Oz” and its movie adaptation.

Classroom Discussion, Part 1: Ask students to read the book and to jot down some details of clothing, food, transportation that have changed since the late 1930s. What were some examples of prejudice experienced by Frankie and her family? By the African-American staff? In their own families, where are students in the birth order (oldest, youngest, middle)? Do they ever feel like Frankie, trapped in a particular family role (responsible one, jokester, lazy lout, etc.)? Do the students try to break out? What do they do/have they done?

Classroom Writing: Ask students to interview a parent or grandparent to get a view of certain events that is both personal and reflective of childhood at the time. (They can do this orally or ask for written answers.) Kids might ask adults to go back to a certain age–10 years old, for example. Questions might include:

1. What was your family pet? Describe one or two adventures or times you shared with this pet. (Frankie has a dog and a pony.)

2. What was your favorite restaurant as a kid? Name three things about its appearance, sound , or smells that you remember. What dish did you like best? Least? Why?

3. What chores or responsibilities did you have as a kid? Which did you like least? Most? Why?

4. What was your favorite book? Movie? Why? Can you describe the first time you read or saw this?

5. What was your favorite item of clothing? Toy or game? Can you briefly describe?

6. Did you ever witness or experience prejudice? What did you say or do? How do you feel about that incident now?

7. What were some important events of that year (war, presidential election, Civil Rights movement, etc.)? How did you feel about them then?

Students might then take one of these answers and write a short description or fictional tale, much as Stout did.

Classroom Discussion, Part 2:Once they have done the interviewing and writing, ask students what they learned, both about the time period and parent.

www.maryquattlebaum.com

Family can be inspiring, as Shawn Stout discovered when writing her eighth novel

A Tiny Piece of Sky

. In an interview for KidsPost/WashingtonPost, Stout talked about the prejudice her German-American grandfather dealt with right before World War II. Shawn fictionalized her family’s experiences, but she asked her mother and aunts many questions about their childhood. She wanted to convey a child’s perspective of the townspeople’s boycott of her grandfather’s restaurant and of their (false) perception of him as a German spy.

Family can be inspiring, as Shawn Stout discovered when writing her eighth novel

A Tiny Piece of Sky

. In an interview for KidsPost/WashingtonPost, Stout talked about the prejudice her German-American grandfather dealt with right before World War II. Shawn fictionalized her family’s experiences, but she asked her mother and aunts many questions about their childhood. She wanted to convey a child’s perspective of the townspeople’s boycott of her grandfather’s restaurant and of their (false) perception of him as a German spy.

Below are writing lessons for the classroom or for individual writers ages 8 and up. Stout’s website http://shawnkstout.com/ includes a teachers’ guide.

RETURN TO THE PAST: As the youngest in her family, 10-year-old Frankie Baum feels she lacks the respect and privileges accorded her two older siblings. She is determined to prove that her father is no spy. As she gets to know some of the African American staff in her father’s restaurant, Frankie also becomes more aware of the injustices suffered by blacks in the segregated Maryland town. She speaks frequently about her favorite book “The Wizard of Oz” and its movie adaptation.

Classroom Discussion, Part 1: Ask students to read the book and to jot down some details of clothing, food, transportation that have changed since the late 1930s. What were some examples of prejudice experienced by Frankie and her family? By the African-American staff? In their own families, where are students in the birth order (oldest, youngest, middle)? Do they ever feel like Frankie, trapped in a particular family role (responsible one, jokester, lazy lout, etc.)? Do the students try to break out? What do they do/have they done?

Classroom Writing: Ask students to interview a parent or grandparent to get a view of certain events that is both personal and reflective of childhood at the time. (They can do this orally or ask for written answers.) Kids might ask adults to go back to a certain age–10 years old, for example. Questions might include:

1. What was your family pet? Describe one or two adventures or times you shared with this pet. (Frankie has a dog and a pony.)

2. What was your favorite restaurant as a kid? Name three things about its appearance, sound , or smells that you remember. What dish did you like best? Least? Why?

3. What chores or responsibilities did you have as a kid? Which did you like least? Most? Why?

4. What was your favorite book? Movie? Why? Can you describe the first time you read or saw this?

5. What was your favorite item of clothing? Toy or game? Can you briefly describe?

6. Did you ever witness or experience prejudice? What did you say or do? How do you feel about that incident now?

7. What were some important events of that year (war, presidential election, Civil Rights movement, etc.)? How did you feel about them then?

Students might then take one of these answers and write a short description or fictional tale, much as Stout did.

Classroom Discussion, Part 2:Once they have done the interviewing and writing, ask students what they learned, both about the time period and parent.

www.maryquattlebaum.com

Published on May 30, 2016 14:00

May 23, 2016

MAKING THE MOST OF A FIELD TRIP

by Karen Leggett Abouraya

This week I’m sharing a book for you – the grown-ups – because it is filled with such good ideas for writing and learning. When Uma Krishnaswami wasn’t busy writing her own children’s books, she wrote Beyond the Field Trip: Teaching and Learning in Public Places.

Uma wants students to be “actively engaged as learners, framing questions and working toward greater levels of understanding,” whether they are visiting a museum, a park or just the center of town.

She recommends planning backwards.

“Figure out what the ultimate product of the study will be. Then work back to find all the activities you will need to use to get there. What you are doing is building bridges between what students know already, and what you anticipate they will know when you have completed the sequence of activities. The place you visit is one ingredient in this process. The visit is not in itself the objective.”

Let’s start with one of Uma’s own picture books, Out of the Way! Out of the Way! about a tree whose role and importance in the center of a village changes as the village becomes crowded, people age, roads are built and everyone is in a hurry.

For one old man, the tree reminds him of stories his father and mother and grandfather told him long ago.

“Even today, those stories are told and retold,as the traffic rattles pastgoing from here to there and back again.But sometimes the drivers of cardsand buses and trucksand vans and tractors

Stop and stay a while… and listen.”

So after you’ve all read Out of the Way, have the children think about their own town or neighborhood. Ask them to write about or draw something that has changed – a new building, a different store, a new park. Ask the students to write some questions they could ask people who lived in the neighborhood before these changes.

Make a plan to visit a park, the library or even a nearby mall. Ask children to write a description of what they see while they are right there. Encourage them to observe carefully, soaking in as many visual and sensory experiences as possible. Try to arrange a meeting with some older residents - perhaps from a nearby senior center, older staff members at the school or family members of the students - so students can ask questions…and listen. Record the conversations if possible.

Back in the classroom, the children can each write their own paragraph or poem or draw a picture recalling what the older residents had to say. This can also be a group writing project combining the recollections of all the students. Uma notes that “cooperative rather than competitive activities in all phases of a place-based learning program will make for more authentic and participatory learning on everyone’s part.” If there is time for a larger production, plan a celebration including the older residents to share the students’ stories, poems and pictures. As Uma notes, “outcome events crown your program.”

http://childrensbookguild.org/karen-leggett-abouraya

This week I’m sharing a book for you – the grown-ups – because it is filled with such good ideas for writing and learning. When Uma Krishnaswami wasn’t busy writing her own children’s books, she wrote Beyond the Field Trip: Teaching and Learning in Public Places.

Uma wants students to be “actively engaged as learners, framing questions and working toward greater levels of understanding,” whether they are visiting a museum, a park or just the center of town.

She recommends planning backwards.

“Figure out what the ultimate product of the study will be. Then work back to find all the activities you will need to use to get there. What you are doing is building bridges between what students know already, and what you anticipate they will know when you have completed the sequence of activities. The place you visit is one ingredient in this process. The visit is not in itself the objective.”

Let’s start with one of Uma’s own picture books, Out of the Way! Out of the Way! about a tree whose role and importance in the center of a village changes as the village becomes crowded, people age, roads are built and everyone is in a hurry.

For one old man, the tree reminds him of stories his father and mother and grandfather told him long ago.

“Even today, those stories are told and retold,as the traffic rattles pastgoing from here to there and back again.But sometimes the drivers of cardsand buses and trucksand vans and tractors

Stop and stay a while… and listen.”

So after you’ve all read Out of the Way, have the children think about their own town or neighborhood. Ask them to write about or draw something that has changed – a new building, a different store, a new park. Ask the students to write some questions they could ask people who lived in the neighborhood before these changes.

Make a plan to visit a park, the library or even a nearby mall. Ask children to write a description of what they see while they are right there. Encourage them to observe carefully, soaking in as many visual and sensory experiences as possible. Try to arrange a meeting with some older residents - perhaps from a nearby senior center, older staff members at the school or family members of the students - so students can ask questions…and listen. Record the conversations if possible.

Back in the classroom, the children can each write their own paragraph or poem or draw a picture recalling what the older residents had to say. This can also be a group writing project combining the recollections of all the students. Uma notes that “cooperative rather than competitive activities in all phases of a place-based learning program will make for more authentic and participatory learning on everyone’s part.” If there is time for a larger production, plan a celebration including the older residents to share the students’ stories, poems and pictures. As Uma notes, “outcome events crown your program.”

http://childrensbookguild.org/karen-leggett-abouraya

Published on May 23, 2016 14:00

May 16, 2016

JUST-SO FUN AND FACTS

by Jacqueline Jules

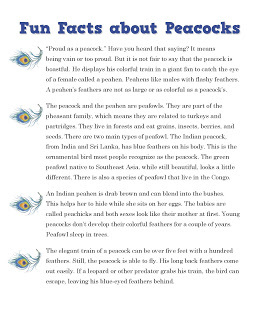

The Elephant’s Child, Rudyard Kipling’s wonderful just-so story is a staple of children’s literature. Children never fail to be amused by this zany explanation for why the elephant has such a long trunk. They also love retellings of why the chipmunk has stripes or why the zebra has stripes.

Personally, as an avid bird lover, I have always been fascinated by traditional tales about why each bird species has such distinctive feathers. There are tales from around the world depicting a time when birds were naked and not at all happy about it. “How Buzzard Got His Feathers” from the Iroquois is a famous one. There are also stories of birds who borrowed or stole feathers from other birds. Authors often take a pinch from one story and a pinch from another to create something entirely new. And that’s what I did when I decided to write an explanation for why the peacock has such amazing plumage.

In Feathers for Peacock, I dispute the old saying, “Proud as a peacock.” Is the peacock really boastful or vain? Peahens, the female of the peafowl species, like males with flashy colors. When the peacock displays his feathers in a giant fan, he is trying to catch a wife so he can become a daddy. Is that so wrong? In my mind, the peacock got a bad rap. He is no more boastful than a bat is blind. Besides, how could I write a just-so story saying that the peacock was awarded a gorgeous appearance as some kind of punishment? Wouldn’t that be counter to all sense of fairness?

In Feathers for Peacock, the poor peacock arrives late on the day all the other birds receive their warm colorful feathers. No one had remembered to invite him to the party. Peacock is left shivering and crying. When his friends see the mistake, the community responds humanely, and Peacock, rather than being an example of vanity, becomes an example of generosity and kindness.

Ask your students to brainstorm sayings about animals such as “slow as a snail,” “fast as a cheetah,” “lazy as a sloth.” Afterward, challenge them to write a story about how that animal behavior came to be. Encourage your students to be critical thinkers and research if the adage is actually true. For example, “Blind as a bat.”

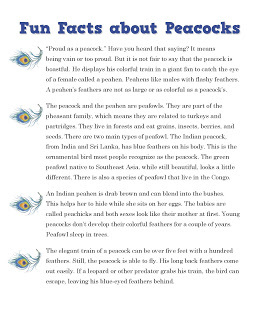

Choosing a distinctive trait of an animal and explaining why it came to be in a story is a fun exercise for writers of any age. Go one step further the way I did in Feathers for Peacock and ask your students to add a nonfiction addendum called Fun Facts About (whatever animal the story is about).

Animal stories provide a perfect opportunity for creative thinking and research.

Happy Writing!

www.jacquelinejules.com

The Elephant’s Child, Rudyard Kipling’s wonderful just-so story is a staple of children’s literature. Children never fail to be amused by this zany explanation for why the elephant has such a long trunk. They also love retellings of why the chipmunk has stripes or why the zebra has stripes.

Personally, as an avid bird lover, I have always been fascinated by traditional tales about why each bird species has such distinctive feathers. There are tales from around the world depicting a time when birds were naked and not at all happy about it. “How Buzzard Got His Feathers” from the Iroquois is a famous one. There are also stories of birds who borrowed or stole feathers from other birds. Authors often take a pinch from one story and a pinch from another to create something entirely new. And that’s what I did when I decided to write an explanation for why the peacock has such amazing plumage.

In Feathers for Peacock, I dispute the old saying, “Proud as a peacock.” Is the peacock really boastful or vain? Peahens, the female of the peafowl species, like males with flashy colors. When the peacock displays his feathers in a giant fan, he is trying to catch a wife so he can become a daddy. Is that so wrong? In my mind, the peacock got a bad rap. He is no more boastful than a bat is blind. Besides, how could I write a just-so story saying that the peacock was awarded a gorgeous appearance as some kind of punishment? Wouldn’t that be counter to all sense of fairness?

In Feathers for Peacock, the poor peacock arrives late on the day all the other birds receive their warm colorful feathers. No one had remembered to invite him to the party. Peacock is left shivering and crying. When his friends see the mistake, the community responds humanely, and Peacock, rather than being an example of vanity, becomes an example of generosity and kindness.

Ask your students to brainstorm sayings about animals such as “slow as a snail,” “fast as a cheetah,” “lazy as a sloth.” Afterward, challenge them to write a story about how that animal behavior came to be. Encourage your students to be critical thinkers and research if the adage is actually true. For example, “Blind as a bat.”

Choosing a distinctive trait of an animal and explaining why it came to be in a story is a fun exercise for writers of any age. Go one step further the way I did in Feathers for Peacock and ask your students to add a nonfiction addendum called Fun Facts About (whatever animal the story is about).

Animal stories provide a perfect opportunity for creative thinking and research.

Happy Writing!

www.jacquelinejules.com

Published on May 16, 2016 14:00

May 9, 2016

CHARACTER HAIKU

Guest Post by Claudia Mills

As a child I loved to write poetry. As an adult, I’ve felt too intimidated even to try, with one exception. I love to write poetry “by” the characters in my stories. I created child poet characters in a number of books, such as Lizzie at Last and Dinah Forever, and had tons of fun writing poems that Lizzie and Dinah might have written. There is something liberating about writing poems under an alias. It frees me from fear that my poem won’t be good enough, because after all, this isn’t really “my” poem, it’s Lizzie’s or Dinah’s.

In my forthcoming book The Trouble with Babies, the third book in my Nora Notebooks series, the kids in Nora’s class are writing haiku for a poetry unit. So I had the challenge of writing haiku for each featured character in the class.

Emma dotes on her cat, Precious Cupcake, so I gave Emma a cat-loving haiku:

Precious Cupcakeby Emma

My cat is the best.White, soft, fluffy, blue eyes, tail.She is the cutest.

Critter-loving Amy is disappointed that her mom won’t let her get a pet snake:

When I Grow Upby Amy

When I’m a mom some-Day, my kids can have ten snakesAnd I’ll say “Hooray!”

Tamara is the class dancer:

Hip Hopby Tamara

When I start to danceMy feet have their own ideas.My body follows.

After explaining the classic haiku structural pattern of three short lines with 5-7-5 syllables, have students write haiku “by” the characters in a favorite book, or a book report selection, or a classroom read-aloud.

If students will be using a common text, ask them collectively to recall as many characters as they can, listing the names on the board for easy reference. As each character is mentioned, have students refresh each others’ memories about key traits or scenes in which they appear. Then it’s time to start writing.

It can be fun to compare student poems written “by” the same character. If the text is Charlotte’s Web, for example, all kinds of poems “by” Wilbur may emerge:

I may be a runt. But I can be terrific. And radiant, too.

Or:

I’m glad I’m a pig. But I hope no one makes me Into a pork chop!

Or: The best kind of friend Is a spider who can write Words into her web.

Note that this last poem is aboutCharlotte, but written by Wilbur, as he reflects on Charlotte as wonderful friend. But if students get confused and write their poems about, rather than by, their chosen character, they are still generating poetry and linking it with their insights into literature.

Once you get started writing this kind of short verse, it’s hard to stop. That’s the power – and pleasure – of character haiku.

BIO: Claudia Mills is the author of over 50 books for young readers, including How Oliver Olson Changed the World (an ALA Notable Book of the Year) and The Trouble with Ants (starred review in Publishers Weekly), as well as the Franklin School Friends series of chapter books from Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Claudia lives in Boulder, Colorado, with her family and her cat, Snickers. Visit her at www.claudiamillsauthor.com.

BIO: Claudia Mills is the author of over 50 books for young readers, including How Oliver Olson Changed the World (an ALA Notable Book of the Year) and The Trouble with Ants (starred review in Publishers Weekly), as well as the Franklin School Friends series of chapter books from Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Claudia lives in Boulder, Colorado, with her family and her cat, Snickers. Visit her at www.claudiamillsauthor.com.

As a child I loved to write poetry. As an adult, I’ve felt too intimidated even to try, with one exception. I love to write poetry “by” the characters in my stories. I created child poet characters in a number of books, such as Lizzie at Last and Dinah Forever, and had tons of fun writing poems that Lizzie and Dinah might have written. There is something liberating about writing poems under an alias. It frees me from fear that my poem won’t be good enough, because after all, this isn’t really “my” poem, it’s Lizzie’s or Dinah’s.

In my forthcoming book The Trouble with Babies, the third book in my Nora Notebooks series, the kids in Nora’s class are writing haiku for a poetry unit. So I had the challenge of writing haiku for each featured character in the class.

Emma dotes on her cat, Precious Cupcake, so I gave Emma a cat-loving haiku:

Precious Cupcakeby Emma

My cat is the best.White, soft, fluffy, blue eyes, tail.She is the cutest.

Critter-loving Amy is disappointed that her mom won’t let her get a pet snake:

When I Grow Upby Amy

When I’m a mom some-Day, my kids can have ten snakesAnd I’ll say “Hooray!”

Tamara is the class dancer:

Hip Hopby Tamara

When I start to danceMy feet have their own ideas.My body follows.

After explaining the classic haiku structural pattern of three short lines with 5-7-5 syllables, have students write haiku “by” the characters in a favorite book, or a book report selection, or a classroom read-aloud.

If students will be using a common text, ask them collectively to recall as many characters as they can, listing the names on the board for easy reference. As each character is mentioned, have students refresh each others’ memories about key traits or scenes in which they appear. Then it’s time to start writing.

It can be fun to compare student poems written “by” the same character. If the text is Charlotte’s Web, for example, all kinds of poems “by” Wilbur may emerge:

I may be a runt. But I can be terrific. And radiant, too.

Or:

I’m glad I’m a pig. But I hope no one makes me Into a pork chop!

Or: The best kind of friend Is a spider who can write Words into her web.

Note that this last poem is aboutCharlotte, but written by Wilbur, as he reflects on Charlotte as wonderful friend. But if students get confused and write their poems about, rather than by, their chosen character, they are still generating poetry and linking it with their insights into literature.

Once you get started writing this kind of short verse, it’s hard to stop. That’s the power – and pleasure – of character haiku.

BIO: Claudia Mills is the author of over 50 books for young readers, including How Oliver Olson Changed the World (an ALA Notable Book of the Year) and The Trouble with Ants (starred review in Publishers Weekly), as well as the Franklin School Friends series of chapter books from Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Claudia lives in Boulder, Colorado, with her family and her cat, Snickers. Visit her at www.claudiamillsauthor.com.

BIO: Claudia Mills is the author of over 50 books for young readers, including How Oliver Olson Changed the World (an ALA Notable Book of the Year) and The Trouble with Ants (starred review in Publishers Weekly), as well as the Franklin School Friends series of chapter books from Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Claudia lives in Boulder, Colorado, with her family and her cat, Snickers. Visit her at www.claudiamillsauthor.com.

Published on May 09, 2016 14:00

May 2, 2016

Ann McCallum Wants Kids to Eat Their Homework!

by Joan Waites

We have all heard the excuse “the dog ate my homework” when a child forgets to bring in an assignment to school. But, what if you told a student to “eat their homework?” You would definitely get their attention, and they just might learn math, science and history facts without even realizing it.

Author Ann McCallum has a unique approach to writing books that engage and entertain students while learning important content. I recently spoke to Ann about these books came to be.

1. Tell us a little about your background, and what inspired you to write books for children?

I’m a mom and a teacher. Now I teach high school students from other countries how to communicate in English. I’ve also taught in a one-room schoolhouse (A remote community in Northern Canada during my first year out of college), in two elementary schools, and at the college level at a university in the United Arab Emirates. Writing children’s books is what I love best. I have inspiration all around: the antics of my own kids growing up, my various students, and my subtle observation of the children in my neighborhood. Plus, I’ve always loved reading children’s books. Even now, I’ll read 10 children’s books for every one adult book.

2. The "Eat Your Homework" series of books is such a unique take on teaching math, history, and science. How did you come up with the idea to combine cooking and teaching these subjects?

I first thought about writing a book and in particular the “Eat Your Homework” children’s books when I was teaching math in elementary school several years ago. One day before Winter Break I had my students make mathematical gingerbread houses—they had to show examples of math in their finished products. The kids were ecstatic and their math connections were amazing. My idea to teach math through food took root, though funny enough, “Eat Your Math Homework” was the fourth book I had published. Cooking and math fits so nicely together not only for the obvious tie-ins like temperature and measuring, but because cooking is a motivating and kid-friendly activity that can serve as a springboard to learning. Take Fibonacci Snack sticks which focus on patterns. Making kebobs with fruit is healthy and fun. Add patterning, and there you have an easy math activity. Depending on the age of the child, you can get into the Fibonacci sequence which is a little more complex, or you can create a more simple pattern with fruit. The food and math connection involves looking at the world in a new—and delicious—way. Similarly, the relationship between science or history and food is just as tasty!

3. There must have been a lot of experimenting happening in your kitchen! How did you choose the recipes that would match the facts you were highlighting in your books?

Oh yes! All that time in the kitchen was really fun. I came up with the concepts I wanted to cover first and then the recipes. Next, I headed to the kitchen to create the original recipes. I had to build every recipe multiple times, measuring ingredients carefully and taking notes on things like pan size and oven temperature. One of my favorite experiments was when I worked to develop Invisible Ink Snack Pockets for the “Eat Your Science” book. I wanted to re-create a situation like painting lemon juice on paper and having the juice become visible when you put the paper near a heat source. My recipe takes this idea, but the invisible, edible “ink” is painted on a pizza dough pocket with a clean paintbrush or cotton swab. When heated in the oven—voila—the printing becomes visible!

4. What kind of reactions have you gotten from your young readers?

I have received fantastic enthusiasm whenever I’ve taken my books and ideas in front of young people. Kids are naturally curious. Even reluctant math or science kids have told me how much they now love the subjects. With the history book, young people have also told me how much they love connecting food to the topics in the book. George Washington and homemade ice-cream? Yum! One of my favorite questions of all time came from a young child during one of my Skype author visits. He asked me, “How much ink does it take to make a book?” I admit I was stumped with that one. However, I went to my publisher and found out that each “Eat Your Homework” book takes about 3 ounces of ink to produce. Amazing.

5. Are there any more "Eat Your Homework" books in the works and what are you working on next?

You know—I’m not sure. I keep thinking that we now need an “Eat Your Language Arts Homework” book, but I’m not sure how to write it. . . yet. I’ll keep thinking! In the meantime, I have a couple of picture books in the works as well as a middle grade novel. I plan to spend some wonderful, long summer days writing these and more books. Thank you for asking!

Thanks, Ann for stopping by!

www.joanwaites.com

We have all heard the excuse “the dog ate my homework” when a child forgets to bring in an assignment to school. But, what if you told a student to “eat their homework?” You would definitely get their attention, and they just might learn math, science and history facts without even realizing it.

Author Ann McCallum has a unique approach to writing books that engage and entertain students while learning important content. I recently spoke to Ann about these books came to be.

1. Tell us a little about your background, and what inspired you to write books for children?

I’m a mom and a teacher. Now I teach high school students from other countries how to communicate in English. I’ve also taught in a one-room schoolhouse (A remote community in Northern Canada during my first year out of college), in two elementary schools, and at the college level at a university in the United Arab Emirates. Writing children’s books is what I love best. I have inspiration all around: the antics of my own kids growing up, my various students, and my subtle observation of the children in my neighborhood. Plus, I’ve always loved reading children’s books. Even now, I’ll read 10 children’s books for every one adult book.

2. The "Eat Your Homework" series of books is such a unique take on teaching math, history, and science. How did you come up with the idea to combine cooking and teaching these subjects?

I first thought about writing a book and in particular the “Eat Your Homework” children’s books when I was teaching math in elementary school several years ago. One day before Winter Break I had my students make mathematical gingerbread houses—they had to show examples of math in their finished products. The kids were ecstatic and their math connections were amazing. My idea to teach math through food took root, though funny enough, “Eat Your Math Homework” was the fourth book I had published. Cooking and math fits so nicely together not only for the obvious tie-ins like temperature and measuring, but because cooking is a motivating and kid-friendly activity that can serve as a springboard to learning. Take Fibonacci Snack sticks which focus on patterns. Making kebobs with fruit is healthy and fun. Add patterning, and there you have an easy math activity. Depending on the age of the child, you can get into the Fibonacci sequence which is a little more complex, or you can create a more simple pattern with fruit. The food and math connection involves looking at the world in a new—and delicious—way. Similarly, the relationship between science or history and food is just as tasty!

3. There must have been a lot of experimenting happening in your kitchen! How did you choose the recipes that would match the facts you were highlighting in your books?

Oh yes! All that time in the kitchen was really fun. I came up with the concepts I wanted to cover first and then the recipes. Next, I headed to the kitchen to create the original recipes. I had to build every recipe multiple times, measuring ingredients carefully and taking notes on things like pan size and oven temperature. One of my favorite experiments was when I worked to develop Invisible Ink Snack Pockets for the “Eat Your Science” book. I wanted to re-create a situation like painting lemon juice on paper and having the juice become visible when you put the paper near a heat source. My recipe takes this idea, but the invisible, edible “ink” is painted on a pizza dough pocket with a clean paintbrush or cotton swab. When heated in the oven—voila—the printing becomes visible!

4. What kind of reactions have you gotten from your young readers?

I have received fantastic enthusiasm whenever I’ve taken my books and ideas in front of young people. Kids are naturally curious. Even reluctant math or science kids have told me how much they now love the subjects. With the history book, young people have also told me how much they love connecting food to the topics in the book. George Washington and homemade ice-cream? Yum! One of my favorite questions of all time came from a young child during one of my Skype author visits. He asked me, “How much ink does it take to make a book?” I admit I was stumped with that one. However, I went to my publisher and found out that each “Eat Your Homework” book takes about 3 ounces of ink to produce. Amazing.

5. Are there any more "Eat Your Homework" books in the works and what are you working on next?

You know—I’m not sure. I keep thinking that we now need an “Eat Your Language Arts Homework” book, but I’m not sure how to write it. . . yet. I’ll keep thinking! In the meantime, I have a couple of picture books in the works as well as a middle grade novel. I plan to spend some wonderful, long summer days writing these and more books. Thank you for asking!

Thanks, Ann for stopping by!

www.joanwaites.com

Published on May 02, 2016 14:00

April 25, 2016

I'M NOT--Writing About Fears with Peep and Egg

by Laura Gehl

In Peep and Egg: I’m Not Hatching, Egg is scared of everything—from the too-high roof of the hen house to the too-dark sky at night. Egg wants to stay inside of her nice, cozy, SAFE shell.

When I present Peep and Egg to school groups, I ask kids to think about their own fears. What would make them want to stay inside their eggs?

When Egg finally hatches, it is because she wants to be with Peep, and because she wants to read a story. I ask students, “What would make you hatch out of your egg? What do you love enough that you would come out of your safe, cozy egg for it?”

In your classroom, you may want to have each student make a chart—one half of the paper for What Would Make Me Stay in My Egg and one half of the paper for What Would Make Me Hatch. Ask students to write a list, or draw pictures, on each side.

(So far, I’ve found sharks to be the most popular answer for What Would Make Me Stay in My Egg and ice cream to be the most popular answer for What Would Make Me Hatch.)

Peep and Egg: I’m Not Hatchingis the first in a series of books that will include Peep and Egg: I’m Not Trick or Treating, Peep and Egg: I’m Not Taking a Bath, and Peep and Egg: I’m Not Eating That.

Ask your students to think about an I’m Nottitle that reflects their own fears. Ask, “What would YOU be scared to do?” I often tell school groups that my title would be I’m Not Skydiving.

Next, ask students to write or tell an I’m Notstory, with the story primarily written in dialogue like Peep and Egg. A student could use the characters Peep and Egg, she could use herself and a parent (“I’m Not Trying Out for the School Play!”) or she might use a scared penguin and a comforting polar bear (“I’m Not Ice Skating!”). Anything goes!

Writing I’m Not stories can help students think about their own fears in a humorous way. I’m Not stories can also help kids remember that we can overcome our fears, although we may need a special someone like Peep to help us break out of our shells!

Laura Gehl is NOT skydiving! But she IS the author of One Big Pair Of Underwear, a Charlotte Zolotow Highly Commended Title, International Literacy Association Honor Book, and Booklist Books for Youth Editors’ Choice for 2014; Hare And Tortoise Race Across Israel and And Then Another Sheep Turned Up (both PJ library selections for 2015 and 2016); and Peep And Egg: I’m Not Hatching, an Amazon Best Book of the Month for February 2016. A former science and reading teacher, Laura also writes about science for children and adults. She lives in Chevy Chase, Maryland with her husband and four children. Visit Laura online at www.lauragehl.com.

Laura Gehl is NOT skydiving! But she IS the author of One Big Pair Of Underwear, a Charlotte Zolotow Highly Commended Title, International Literacy Association Honor Book, and Booklist Books for Youth Editors’ Choice for 2014; Hare And Tortoise Race Across Israel and And Then Another Sheep Turned Up (both PJ library selections for 2015 and 2016); and Peep And Egg: I’m Not Hatching, an Amazon Best Book of the Month for February 2016. A former science and reading teacher, Laura also writes about science for children and adults. She lives in Chevy Chase, Maryland with her husband and four children. Visit Laura online at www.lauragehl.com.

In Peep and Egg: I’m Not Hatching, Egg is scared of everything—from the too-high roof of the hen house to the too-dark sky at night. Egg wants to stay inside of her nice, cozy, SAFE shell.

When I present Peep and Egg to school groups, I ask kids to think about their own fears. What would make them want to stay inside their eggs?

When Egg finally hatches, it is because she wants to be with Peep, and because she wants to read a story. I ask students, “What would make you hatch out of your egg? What do you love enough that you would come out of your safe, cozy egg for it?”

In your classroom, you may want to have each student make a chart—one half of the paper for What Would Make Me Stay in My Egg and one half of the paper for What Would Make Me Hatch. Ask students to write a list, or draw pictures, on each side.

(So far, I’ve found sharks to be the most popular answer for What Would Make Me Stay in My Egg and ice cream to be the most popular answer for What Would Make Me Hatch.)

Peep and Egg: I’m Not Hatchingis the first in a series of books that will include Peep and Egg: I’m Not Trick or Treating, Peep and Egg: I’m Not Taking a Bath, and Peep and Egg: I’m Not Eating That.

Ask your students to think about an I’m Nottitle that reflects their own fears. Ask, “What would YOU be scared to do?” I often tell school groups that my title would be I’m Not Skydiving.

Next, ask students to write or tell an I’m Notstory, with the story primarily written in dialogue like Peep and Egg. A student could use the characters Peep and Egg, she could use herself and a parent (“I’m Not Trying Out for the School Play!”) or she might use a scared penguin and a comforting polar bear (“I’m Not Ice Skating!”). Anything goes!

Writing I’m Not stories can help students think about their own fears in a humorous way. I’m Not stories can also help kids remember that we can overcome our fears, although we may need a special someone like Peep to help us break out of our shells!

Laura Gehl is NOT skydiving! But she IS the author of One Big Pair Of Underwear, a Charlotte Zolotow Highly Commended Title, International Literacy Association Honor Book, and Booklist Books for Youth Editors’ Choice for 2014; Hare And Tortoise Race Across Israel and And Then Another Sheep Turned Up (both PJ library selections for 2015 and 2016); and Peep And Egg: I’m Not Hatching, an Amazon Best Book of the Month for February 2016. A former science and reading teacher, Laura also writes about science for children and adults. She lives in Chevy Chase, Maryland with her husband and four children. Visit Laura online at www.lauragehl.com.

Laura Gehl is NOT skydiving! But she IS the author of One Big Pair Of Underwear, a Charlotte Zolotow Highly Commended Title, International Literacy Association Honor Book, and Booklist Books for Youth Editors’ Choice for 2014; Hare And Tortoise Race Across Israel and And Then Another Sheep Turned Up (both PJ library selections for 2015 and 2016); and Peep And Egg: I’m Not Hatching, an Amazon Best Book of the Month for February 2016. A former science and reading teacher, Laura also writes about science for children and adults. She lives in Chevy Chase, Maryland with her husband and four children. Visit Laura online at www.lauragehl.com.

Published on April 25, 2016 14:00

April 18, 2016

Writing Connections with Dan Gutman

by Mary Quattlebaum

Like a master alchemist, Dan Gutman can take ordinary stuff and turn it into comic gold. As the best-selling author of 125 books, he knows how to keep kids laughing as they turn the pages. I recently interviewed him for KidsPost/WashingtonPost about the first book (The Lincoln Project) in his new history series, “Flashback Four.” With its time-travel shenanigans, the new series is sure to be as popular as Gutman’s “My Weird School” and “Baseball Card Adventure” series.

Below are writing lessons for the classroom or for individual writers ages 8 and up. Gutman’s website www.dangutman.comincludes puzzles and games related to his books.

VIEWS OF HISTORY: In the “Lincoln Project,” the four main characters travel back to the time of the Gettysburg Address, in 1863, for a wild adventure. But each experiences that time differently, depending on race and gender. Luke and Julia are white, Isabel is a scholarly Hispanic girl and David is an African American boy.

Classroom Discussion: Ask students to read the book and to jot down differences between the way boys and girls dressed or were treated. How about African American and white people? What is David worried about?

Classroom Writing:Ask each student to list what they would have liked/disliked/been worried about if they had traveled on Miss Z’s invention back to Gettysburg, in 1863. What would have been their favorite thing? Now, ask them to be someone from a different race and/or gender and do the same thing. How were the answers different?

Classroom Writing: Miss Z has tapped you to be one of her time-traveling students. What point in time would you like to travel back to—and where? (It doesn’t have to be the United States.) What important moment would you take a photo of? Write Miss Z a letter explaining (1) why you are the best person to go, (2) why this place and time are important to visit, and (3) why it is important that this moment be photographed. To prepare the most persuasive letters, ask students to do some research into their point in history. Ask them to write down what excites them and what they may be afraid of. How do they think they will be treated back then? Give some reasons why.

www.maryquattlebaum.com

Like a master alchemist, Dan Gutman can take ordinary stuff and turn it into comic gold. As the best-selling author of 125 books, he knows how to keep kids laughing as they turn the pages. I recently interviewed him for KidsPost/WashingtonPost about the first book (The Lincoln Project) in his new history series, “Flashback Four.” With its time-travel shenanigans, the new series is sure to be as popular as Gutman’s “My Weird School” and “Baseball Card Adventure” series.

Below are writing lessons for the classroom or for individual writers ages 8 and up. Gutman’s website www.dangutman.comincludes puzzles and games related to his books.

VIEWS OF HISTORY: In the “Lincoln Project,” the four main characters travel back to the time of the Gettysburg Address, in 1863, for a wild adventure. But each experiences that time differently, depending on race and gender. Luke and Julia are white, Isabel is a scholarly Hispanic girl and David is an African American boy.

Classroom Discussion: Ask students to read the book and to jot down differences between the way boys and girls dressed or were treated. How about African American and white people? What is David worried about?

Classroom Writing:Ask each student to list what they would have liked/disliked/been worried about if they had traveled on Miss Z’s invention back to Gettysburg, in 1863. What would have been their favorite thing? Now, ask them to be someone from a different race and/or gender and do the same thing. How were the answers different?

Classroom Writing: Miss Z has tapped you to be one of her time-traveling students. What point in time would you like to travel back to—and where? (It doesn’t have to be the United States.) What important moment would you take a photo of? Write Miss Z a letter explaining (1) why you are the best person to go, (2) why this place and time are important to visit, and (3) why it is important that this moment be photographed. To prepare the most persuasive letters, ask students to do some research into their point in history. Ask them to write down what excites them and what they may be afraid of. How do they think they will be treated back then? Give some reasons why.

www.maryquattlebaum.com

Published on April 18, 2016 14:00

Mary Quattlebaum's Blog

- Mary Quattlebaum's profile

- 22 followers

Mary Quattlebaum isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.