Mary Quattlebaum's Blog, page 13

April 11, 2016

Embarrassed? Frightened? Write a Poem!

by Jacqueline Jules

Poetry is a great outlet for expressing strong emotions. The Poetry Friday Anthologies are a wonderful source for poems about first day jitters, disappointments, fears, and other emotional moments students experience on a daily basis. I’d like to share two poems I wrote that your students could use as models to write about their own feelings.

“Embarrassed” appeared in The Poetry Friday Anthology, K-5 Edition,2012.

In this poem, I use food images to describe the feeling of being embarrassed after saying the wrong thing. I say “Words spilled like soda/Now there’s a stain.” Sometimes things slip from our mouths in a sloppy way we didn’t intend. It can feel like being a sloppy eater and having potato chips end up in your hair.

The use of images to describe one’s feelings is a powerful tool in writing, particularly in poetry. Ask your student to think of an embarrassing moment. It can be a time when they said something they were sorry for or it could simply be a time when they dropped something or lost their balance in front of someone they wanted to impress. Can they think of an image to describe their feelings? Can they compare it to another situation or object readers will immediately identify with?

Begin with a freewrite, asking your students to describe the situation in prose, with as many metaphors or similes that come to mind. Freewrites give writers the opportunity to find their images first before trying to rhyme or condense their thoughts into a poem. Sometimes, writers choose words only because they rhyme. Doing a freewrite first can help writers avoid this pitfall.

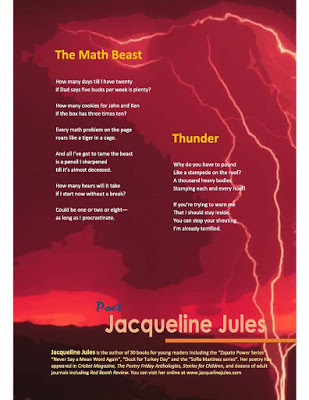

Another strong emotion is fear. Fear of homework. Fear of thunder. Fear of being embarrassed. These poems, “The Math Beast” and “Thunder” appeared in Balloon Lit Journal, August 2015.

In “The Math Beast” I compared math homework and my fear of failing to a tiger roaring in a cage. In “Thunder” I compared the frightening sound of a storm to a stampede of buffalos on the roof.

Ask your students to write about something they fear. Storms? Tests? The High Dive? Monsters? Can they compare their fear to something else?

Once again, begin with a prose freewrite, encouraging your students to identify images before they try to write a poem. Poetry should contain at least one clear picture for the reader and having one in mind before you start is very helpful.

There are so many emotions to write about. Encourage your students to explore emotional terrains and describe their feelings in concrete images.

www.jacquelinejules.com

Poetry is a great outlet for expressing strong emotions. The Poetry Friday Anthologies are a wonderful source for poems about first day jitters, disappointments, fears, and other emotional moments students experience on a daily basis. I’d like to share two poems I wrote that your students could use as models to write about their own feelings.

“Embarrassed” appeared in The Poetry Friday Anthology, K-5 Edition,2012.

In this poem, I use food images to describe the feeling of being embarrassed after saying the wrong thing. I say “Words spilled like soda/Now there’s a stain.” Sometimes things slip from our mouths in a sloppy way we didn’t intend. It can feel like being a sloppy eater and having potato chips end up in your hair.

The use of images to describe one’s feelings is a powerful tool in writing, particularly in poetry. Ask your student to think of an embarrassing moment. It can be a time when they said something they were sorry for or it could simply be a time when they dropped something or lost their balance in front of someone they wanted to impress. Can they think of an image to describe their feelings? Can they compare it to another situation or object readers will immediately identify with?

Begin with a freewrite, asking your students to describe the situation in prose, with as many metaphors or similes that come to mind. Freewrites give writers the opportunity to find their images first before trying to rhyme or condense their thoughts into a poem. Sometimes, writers choose words only because they rhyme. Doing a freewrite first can help writers avoid this pitfall.

Another strong emotion is fear. Fear of homework. Fear of thunder. Fear of being embarrassed. These poems, “The Math Beast” and “Thunder” appeared in Balloon Lit Journal, August 2015.

In “The Math Beast” I compared math homework and my fear of failing to a tiger roaring in a cage. In “Thunder” I compared the frightening sound of a storm to a stampede of buffalos on the roof.

Ask your students to write about something they fear. Storms? Tests? The High Dive? Monsters? Can they compare their fear to something else?

Once again, begin with a prose freewrite, encouraging your students to identify images before they try to write a poem. Poetry should contain at least one clear picture for the reader and having one in mind before you start is very helpful.

There are so many emotions to write about. Encourage your students to explore emotional terrains and describe their feelings in concrete images.

www.jacquelinejules.com

Published on April 11, 2016 14:00

April 4, 2016

Explaining Unfamiliar Words, Concepts, and Facts

Guest Post by Laurie Wallmark

Whether your students are writing fiction or nonfiction, there might be an unfamiliar word, concept, or fact that needs additional explanation. This might be anything from a STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) fact to a sports move, a fantasy world setting to an alien language. Here’s a writing exercise to help your students think about the many techniques available in their writer’s toolbox that will help.

First, as a group exercise, have your students imagine they’re writing a story about a little boy with asthma. Explain that not everyone knows about this disease. Ask for suggestions of how this could be explained in the story.

Here are some possible techniques:· Simplify the definition – it’s a disease where you have trouble breathing· Give an analogy – it’s like trying to breath through a straw· Show an action – describe a character having an asthma attack· Offer an example – character can mention famous people who have asthma · Show in the narrative – the text explains what asthma is· Use a question & answer – have another character asks about the disease

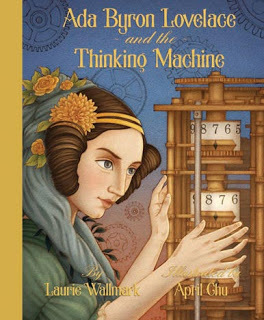

As an example, you can read my book Ada Byron Lovelace and the Thinking Machine and point out how even difficult concepts can be explained using appropriate text techniques. Ada Byron Lovelace was the world’s first computer programmer. In order to appreciate her groundbreaking achievement, the reader needs to understand the concept of an algorithm. Some of the techniques I used to explain this were:· Give a definition – “A set of steps that are followed in order to solve a mathematical problem or to complete a computer process.” · Simplify the definition – “Ada decided to create an algorithm, a set of mathematical instructions.” · Show an action – “Ada broke the problem into a series of simple steps.” · Use an example – “The machine could follow these instructions and solve a complex math problem, one difficult to figure out by hand.”

Now it’s time for the students to do a writing exercise on their own. Have them think of an unfamiliar word, concept, or fact they might need to explain in a story. If they’re having trouble coming up with anything, you can give suggestions such as: cultural or religious traditions, sports terms, or hobby activities. Challenge them to write five or more ways to give an explanation to their reader. At the end of the exercise, have them share their techniques with the class. Have the students discuss which techniques they think work better.

BIO: Laurie Wallmark writes picture books and middle-grades, poetry and prose, fiction and nonfiction. She has an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from VCFA. When not writing, Laurie teaches computer science at Raritan Valley Community College, both to students on campus and in prison. Her debut picture book, Ada Byron Lovelace and the Thinking Machine, received four starred trade reviews (Kirkus, Publishers Weekly, Booklist, and School Library Journal) and several national awards, including Outstanding Science Trade Book. Visit http://www.lauriewallmark.com/

BIO: Laurie Wallmark writes picture books and middle-grades, poetry and prose, fiction and nonfiction. She has an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from VCFA. When not writing, Laurie teaches computer science at Raritan Valley Community College, both to students on campus and in prison. Her debut picture book, Ada Byron Lovelace and the Thinking Machine, received four starred trade reviews (Kirkus, Publishers Weekly, Booklist, and School Library Journal) and several national awards, including Outstanding Science Trade Book. Visit http://www.lauriewallmark.com/

Whether your students are writing fiction or nonfiction, there might be an unfamiliar word, concept, or fact that needs additional explanation. This might be anything from a STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) fact to a sports move, a fantasy world setting to an alien language. Here’s a writing exercise to help your students think about the many techniques available in their writer’s toolbox that will help.

First, as a group exercise, have your students imagine they’re writing a story about a little boy with asthma. Explain that not everyone knows about this disease. Ask for suggestions of how this could be explained in the story.

Here are some possible techniques:· Simplify the definition – it’s a disease where you have trouble breathing· Give an analogy – it’s like trying to breath through a straw· Show an action – describe a character having an asthma attack· Offer an example – character can mention famous people who have asthma · Show in the narrative – the text explains what asthma is· Use a question & answer – have another character asks about the disease

As an example, you can read my book Ada Byron Lovelace and the Thinking Machine and point out how even difficult concepts can be explained using appropriate text techniques. Ada Byron Lovelace was the world’s first computer programmer. In order to appreciate her groundbreaking achievement, the reader needs to understand the concept of an algorithm. Some of the techniques I used to explain this were:· Give a definition – “A set of steps that are followed in order to solve a mathematical problem or to complete a computer process.” · Simplify the definition – “Ada decided to create an algorithm, a set of mathematical instructions.” · Show an action – “Ada broke the problem into a series of simple steps.” · Use an example – “The machine could follow these instructions and solve a complex math problem, one difficult to figure out by hand.”

Now it’s time for the students to do a writing exercise on their own. Have them think of an unfamiliar word, concept, or fact they might need to explain in a story. If they’re having trouble coming up with anything, you can give suggestions such as: cultural or religious traditions, sports terms, or hobby activities. Challenge them to write five or more ways to give an explanation to their reader. At the end of the exercise, have them share their techniques with the class. Have the students discuss which techniques they think work better.

BIO: Laurie Wallmark writes picture books and middle-grades, poetry and prose, fiction and nonfiction. She has an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from VCFA. When not writing, Laurie teaches computer science at Raritan Valley Community College, both to students on campus and in prison. Her debut picture book, Ada Byron Lovelace and the Thinking Machine, received four starred trade reviews (Kirkus, Publishers Weekly, Booklist, and School Library Journal) and several national awards, including Outstanding Science Trade Book. Visit http://www.lauriewallmark.com/

BIO: Laurie Wallmark writes picture books and middle-grades, poetry and prose, fiction and nonfiction. She has an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from VCFA. When not writing, Laurie teaches computer science at Raritan Valley Community College, both to students on campus and in prison. Her debut picture book, Ada Byron Lovelace and the Thinking Machine, received four starred trade reviews (Kirkus, Publishers Weekly, Booklist, and School Library Journal) and several national awards, including Outstanding Science Trade Book. Visit http://www.lauriewallmark.com/

Published on April 04, 2016 14:00

March 28, 2016

Michael Shiner: A True American Original

by Karen Leggett Abouraya

“It is sometimes called the City of Magnificent Distances, but it might with greater propriety be termed the City of Magnificent Intentions…” That’s how Charles Dickens described Washington, D.C., when he visited in 1842. The only compliment he paid to Washington was the “very pleasant and commodious library in the Capitol.”

In Capital Days, Michael Shiner’s Journal and the Growth of Our Nation’s Capital, Tonya Bolden recounts the history of Washington, D.C., often from the point of view of Michael Shiner, born enslaved but able to secure freedom for himself and his family. He spent most of his life working at the Washington Navy Yard, keeping a journal that cataloged some of the city’s most important events, including numerous fires, laying the cornerstone for the Washington Monument and the inauguration of 11 presidents.

Bolden is the winner of the 2016 Children’s Book Guild Nonfiction Award. She is honored for all of her books, including many stories of American history, often from the point of view of African Americans. Bolden will be honored at an Award Luncheon on April 9 in Washington, D.C., and everyone is invited. Find the details here.

Bolden’s books are rich with opportunities for student research and writing.

In addition to Michael Shiner’s journal itself, Capital Days is filled with pictures and stories drawn from original documents. Here is a poster published by the Anti-Slavery Society as part of its campaign to end slavery and slave trading in Washington, D.C.

You can enlarge this poster here.

· Ask students to create their own anti-slavery poster. What would they say or show that might convince legislators to make slavery and slave trading illegal in the nation’s capital?

In 1807, three free black men who could neither read nor write established Bell School near the Washington Navy Yard where they worked. It was the first school for black children in the nation’s capital.

· Have one student pretend to be carpenter George Bell while another interviews him. Why did Mr. Bell think it was important to start a school? Who did he expect to attend the school (boys and girls)? What problems or challenges did he encounter in opening the school? Both students can write newspaper articles based on Mr. Bell’s answers.

Read the full quote about Washington from Charles Dickens, where he writes very disparagingly of “spacious avenues that begin in nothing and lead nowhere.”

· Ask students to write a review of their own city, as if they were writing for Yelp or TripAdvisor.

Reading Michael Shiner’s journal was like having a conversation with him across the dinner table about daily events. In 1861, “they commenced hauling flour from the different warehouses in Washington, D.C., and Georgetown to the Capitol of the United States.” The Capitol – still under construction – would serve as a bakery, barracks and hospital for Union troops.

· Ask students to interview a long time resident of their community – perhaps a relative or resident of a retirement community. Ask about details of a particularly important event in the community or even the nation and turn those details into a narrative description or story.

Capital Days is also an excellent tool to help students learn the importance of good glossaries, thorough footnotes and an index. In her Author’s Note, Bolden calls Shiner a “true American original.”

http://childrensbookguild.org/karen-leggett-abouraya

“It is sometimes called the City of Magnificent Distances, but it might with greater propriety be termed the City of Magnificent Intentions…” That’s how Charles Dickens described Washington, D.C., when he visited in 1842. The only compliment he paid to Washington was the “very pleasant and commodious library in the Capitol.”

In Capital Days, Michael Shiner’s Journal and the Growth of Our Nation’s Capital, Tonya Bolden recounts the history of Washington, D.C., often from the point of view of Michael Shiner, born enslaved but able to secure freedom for himself and his family. He spent most of his life working at the Washington Navy Yard, keeping a journal that cataloged some of the city’s most important events, including numerous fires, laying the cornerstone for the Washington Monument and the inauguration of 11 presidents.

Bolden is the winner of the 2016 Children’s Book Guild Nonfiction Award. She is honored for all of her books, including many stories of American history, often from the point of view of African Americans. Bolden will be honored at an Award Luncheon on April 9 in Washington, D.C., and everyone is invited. Find the details here.

Bolden’s books are rich with opportunities for student research and writing.

In addition to Michael Shiner’s journal itself, Capital Days is filled with pictures and stories drawn from original documents. Here is a poster published by the Anti-Slavery Society as part of its campaign to end slavery and slave trading in Washington, D.C.

You can enlarge this poster here.

· Ask students to create their own anti-slavery poster. What would they say or show that might convince legislators to make slavery and slave trading illegal in the nation’s capital?

In 1807, three free black men who could neither read nor write established Bell School near the Washington Navy Yard where they worked. It was the first school for black children in the nation’s capital.

· Have one student pretend to be carpenter George Bell while another interviews him. Why did Mr. Bell think it was important to start a school? Who did he expect to attend the school (boys and girls)? What problems or challenges did he encounter in opening the school? Both students can write newspaper articles based on Mr. Bell’s answers.

Read the full quote about Washington from Charles Dickens, where he writes very disparagingly of “spacious avenues that begin in nothing and lead nowhere.”

· Ask students to write a review of their own city, as if they were writing for Yelp or TripAdvisor.

Reading Michael Shiner’s journal was like having a conversation with him across the dinner table about daily events. In 1861, “they commenced hauling flour from the different warehouses in Washington, D.C., and Georgetown to the Capitol of the United States.” The Capitol – still under construction – would serve as a bakery, barracks and hospital for Union troops.

· Ask students to interview a long time resident of their community – perhaps a relative or resident of a retirement community. Ask about details of a particularly important event in the community or even the nation and turn those details into a narrative description or story.

Capital Days is also an excellent tool to help students learn the importance of good glossaries, thorough footnotes and an index. In her Author’s Note, Bolden calls Shiner a “true American original.”

http://childrensbookguild.org/karen-leggett-abouraya

Published on March 28, 2016 14:00

March 21, 2016

Creating Amate Bark Paintings

by Joan Waites

Amate bark paintings are a beautiful type of folk art created by the Otomi Indians of Mexico. These paintings are done on paper made from brown and white bark. The art depicts various flowers, birds, reptiles, and other native animals and/or scenes from everyday life using beautiful patterns and vibrant colors.

Students can create their own Amate paintings using brown Kraft paper or cut up pieces of a brown paper bag to simulate the look of bark.

1. Cut paper into the desired size for the project. Students can create individual works or one large collaborative painting.

2. Crumple the paper into a tight ball. Carefully unwrap the paper and smooth it out using hands, a ruler, or if needed, have an adult iron the paper flat.

3. Using a pencil, have students lightly sketch out their designs. Go over pencil lines with a black Sharpie, oil pastel or crayon.

4. Fill in the designs, shapes, and scenes with bright tempera paint, acrylic paint, oil pastels or markers.

After the students have created their artwork, ask them to write a short folk tale featuring one or more of the animals or people featured in their paintings.

www.joanwaites.com

Amate bark paintings are a beautiful type of folk art created by the Otomi Indians of Mexico. These paintings are done on paper made from brown and white bark. The art depicts various flowers, birds, reptiles, and other native animals and/or scenes from everyday life using beautiful patterns and vibrant colors.

Students can create their own Amate paintings using brown Kraft paper or cut up pieces of a brown paper bag to simulate the look of bark.

1. Cut paper into the desired size for the project. Students can create individual works or one large collaborative painting.

2. Crumple the paper into a tight ball. Carefully unwrap the paper and smooth it out using hands, a ruler, or if needed, have an adult iron the paper flat.

3. Using a pencil, have students lightly sketch out their designs. Go over pencil lines with a black Sharpie, oil pastel or crayon.

4. Fill in the designs, shapes, and scenes with bright tempera paint, acrylic paint, oil pastels or markers.

After the students have created their artwork, ask them to write a short folk tale featuring one or more of the animals or people featured in their paintings.

www.joanwaites.com

Published on March 21, 2016 14:00

March 14, 2016

WHAT HAPPENS NEXT?

guest post by Katherine Marsh

Just after midnight, Mary Hayes crept into the kitchen of the Buffalo Asylum for Young Ladies and opened a small door on the side of the enormous cast-iron stove. Then she took a deep breath and shoved herself inside.

These are the first few sentences of my new book, The Door By The Staircase. Want to know what happens next? If you do, then I’ve done my job as a writer.

“What happens next?” is one of the most important questions to make a reader ask. We have a lot of fancy ways of talking about this: suspense, mystery, conflict, foreshadowing, cliffhanger. But these terms all really mean the same thing: Show your reader that something interesting and unusual, something dangerous or scary or magical or problematic, is about to happen. Make them wonder about it enough to turn the page.

The Door by the Staircaseis about magic. Magic works best when you show but also conceal at the same time. That’s a lot like writing. Great writing shows just enough to hook the reader and make them read on but doesn’t rush to give away the whole story.

The first lines of a book are a key place to make your reader wonder what happens next. Here are a few I love:

“’Where’s Papa going with that axe?’ asked Fern to her mother as they were setting the table for breakfast.” (Charlotte’s Webby E.B. White).

“Kouun is good luck in Japanese, and one year my family had none of it.” (The Thing About Luck, Cynthia Kadohata)

“There was a hand in the darkness, and it held a knife.” (The Graveyard Book, Neil Gaiman)

Note that even though only one of these lines starts with an actual question, they all raise intriguing and troubling questions that compel the reader to keep on going: What bad thing could be happening with that axe? And why is Fern’s father marching out with it just before breakfast? What happened to the narrator’s family during the year of bad luck? How bad could it have been? Whose hand was in the darkness? And what were they doing with that knife?

Writing Exercises:

1) Ask students to think of a family story. It could be funny, sad, scary, or exciting. Ask them to come up with a first line or couple lines that would make a reader want to know “what happens next?” Let students read their lines aloud and note the lines that pulled them in most. Afterwards, lead a discussion about the most popular ones: What about them pulled you in? What did they show? What did they conceal or not tell you? How did they make you feel? How did they set up a sense of conflict, tone, or character?

2) There’s more than one way to start a story. Working off another book students have read in your class, ask them to come up with an alternate first line or couple lines that would also draw readers in.

3) Have students come up with a first line or lines for a fictional story. Collect and anonymously read them aloud. Have the students vote on their favorite.

Katherine Marsh is the Edgar-Award-winning author of The Night Tourist, The Twilight Prisoner and Jepp, Who Defied the Stars. Her middle-grade fantasy, The Door By The Staircase, comes out January. In a starred review, School Library Journal called it, “A sparkling tale full of adventure, magic, and folklore.” A onetime high school English teacher and journalist, Katherine lives in Brussels, Belgium with her husband, two children and cat, Egg. You can visit her at www.katherinemarsh.com

Katherine Marsh is the Edgar-Award-winning author of The Night Tourist, The Twilight Prisoner and Jepp, Who Defied the Stars. Her middle-grade fantasy, The Door By The Staircase, comes out January. In a starred review, School Library Journal called it, “A sparkling tale full of adventure, magic, and folklore.” A onetime high school English teacher and journalist, Katherine lives in Brussels, Belgium with her husband, two children and cat, Egg. You can visit her at www.katherinemarsh.com

Just after midnight, Mary Hayes crept into the kitchen of the Buffalo Asylum for Young Ladies and opened a small door on the side of the enormous cast-iron stove. Then she took a deep breath and shoved herself inside.

These are the first few sentences of my new book, The Door By The Staircase. Want to know what happens next? If you do, then I’ve done my job as a writer.

“What happens next?” is one of the most important questions to make a reader ask. We have a lot of fancy ways of talking about this: suspense, mystery, conflict, foreshadowing, cliffhanger. But these terms all really mean the same thing: Show your reader that something interesting and unusual, something dangerous or scary or magical or problematic, is about to happen. Make them wonder about it enough to turn the page.

The Door by the Staircaseis about magic. Magic works best when you show but also conceal at the same time. That’s a lot like writing. Great writing shows just enough to hook the reader and make them read on but doesn’t rush to give away the whole story.

The first lines of a book are a key place to make your reader wonder what happens next. Here are a few I love:

“’Where’s Papa going with that axe?’ asked Fern to her mother as they were setting the table for breakfast.” (Charlotte’s Webby E.B. White).

“Kouun is good luck in Japanese, and one year my family had none of it.” (The Thing About Luck, Cynthia Kadohata)

“There was a hand in the darkness, and it held a knife.” (The Graveyard Book, Neil Gaiman)

Note that even though only one of these lines starts with an actual question, they all raise intriguing and troubling questions that compel the reader to keep on going: What bad thing could be happening with that axe? And why is Fern’s father marching out with it just before breakfast? What happened to the narrator’s family during the year of bad luck? How bad could it have been? Whose hand was in the darkness? And what were they doing with that knife?

Writing Exercises:

1) Ask students to think of a family story. It could be funny, sad, scary, or exciting. Ask them to come up with a first line or couple lines that would make a reader want to know “what happens next?” Let students read their lines aloud and note the lines that pulled them in most. Afterwards, lead a discussion about the most popular ones: What about them pulled you in? What did they show? What did they conceal or not tell you? How did they make you feel? How did they set up a sense of conflict, tone, or character?

2) There’s more than one way to start a story. Working off another book students have read in your class, ask them to come up with an alternate first line or couple lines that would also draw readers in.

3) Have students come up with a first line or lines for a fictional story. Collect and anonymously read them aloud. Have the students vote on their favorite.

Katherine Marsh is the Edgar-Award-winning author of The Night Tourist, The Twilight Prisoner and Jepp, Who Defied the Stars. Her middle-grade fantasy, The Door By The Staircase, comes out January. In a starred review, School Library Journal called it, “A sparkling tale full of adventure, magic, and folklore.” A onetime high school English teacher and journalist, Katherine lives in Brussels, Belgium with her husband, two children and cat, Egg. You can visit her at www.katherinemarsh.com

Katherine Marsh is the Edgar-Award-winning author of The Night Tourist, The Twilight Prisoner and Jepp, Who Defied the Stars. Her middle-grade fantasy, The Door By The Staircase, comes out January. In a starred review, School Library Journal called it, “A sparkling tale full of adventure, magic, and folklore.” A onetime high school English teacher and journalist, Katherine lives in Brussels, Belgium with her husband, two children and cat, Egg. You can visit her at www.katherinemarsh.com

Published on March 14, 2016 17:00

March 7, 2016

Writing Connections with Gene Luen Yang

by Mary Quattlebaum

Gene Luen Yang recently became the fifth National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, succeeding Kate DiCamillo. As the first graphic novelist in this prestigious role, he brings a keen awareness to the interplay of words and art in the creation of engaging stories. In a recent interview for the

The following writing prompts and discussion points connect to Yang’s platform “Reading Without Walls” for the two years of his ambassadorship.

Classroom Discussion: Yang suggests that young people explore new worlds in two ways: (1) read a book on a topic completely new to them, and (2) pick up a book about a character who is different (by race, gender, culture, etc.) from them. Have each student brainstorm topics, coming up with a list of at least five new subjects to explore. Or have them visit the library and check out a book with a completely new type of character.

Writing: Ask students to read their books and then write a short response paper. What did they learn by reading this? What, exactly, was boring? What was surprising? Would they want to learn more? Why or why not?

Classroom Discussion: In his graphic novel, American Born Chinese, Yang draws on some of his own experiences as one of the few Asian-American kids in his middle school. He was sometimes teased and excluded. Writing: Ask students to write about a time when they felt teased or excluded. Was it because of appearance, socioeconomic status, race? How do they feel about the incident now? (These should remain private unless the writer wants to share aloud.)

Additional Resources: The Library of Congress website includes information on past and current National Ambassadors of Young People's Literature.

Check Yang’s website for details about his work as a writer for DC Comics and his graphic novels, including Boxers & Saints and the playful, tech-savvy Secret Coders middle-grade series.

www.maryquattlebaum.com

Gene Luen Yang recently became the fifth National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, succeeding Kate DiCamillo. As the first graphic novelist in this prestigious role, he brings a keen awareness to the interplay of words and art in the creation of engaging stories. In a recent interview for the

The following writing prompts and discussion points connect to Yang’s platform “Reading Without Walls” for the two years of his ambassadorship.

Classroom Discussion: Yang suggests that young people explore new worlds in two ways: (1) read a book on a topic completely new to them, and (2) pick up a book about a character who is different (by race, gender, culture, etc.) from them. Have each student brainstorm topics, coming up with a list of at least five new subjects to explore. Or have them visit the library and check out a book with a completely new type of character.

Writing: Ask students to read their books and then write a short response paper. What did they learn by reading this? What, exactly, was boring? What was surprising? Would they want to learn more? Why or why not?

Classroom Discussion: In his graphic novel, American Born Chinese, Yang draws on some of his own experiences as one of the few Asian-American kids in his middle school. He was sometimes teased and excluded. Writing: Ask students to write about a time when they felt teased or excluded. Was it because of appearance, socioeconomic status, race? How do they feel about the incident now? (These should remain private unless the writer wants to share aloud.)

Additional Resources: The Library of Congress website includes information on past and current National Ambassadors of Young People's Literature.

Check Yang’s website for details about his work as a writer for DC Comics and his graphic novels, including Boxers & Saints and the playful, tech-savvy Secret Coders middle-grade series.

www.maryquattlebaum.com

Published on March 07, 2016 14:00

February 29, 2016

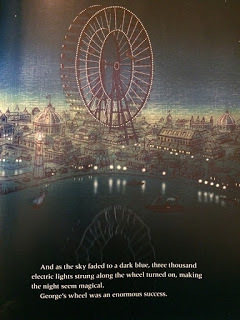

FERRIS WHEEL DREAMS

by Karen Leggett Abouraya

Have you seen a toy or gadget and thought, “I could make a better one than that!” That was exactly what George Ferris thought when he lay in the grass as a boy watching a waterwheel move.

“The boy watched, fascinated. Maybe there is another way to make a wheel go around, he thought.”

Betsy Harvey Kraft tells Ferris’ story in The Fantastic Ferris Wheel: The Story of Inventor George Ferris.

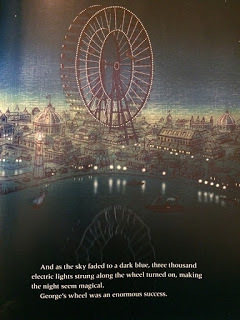

Indeed there was. Ferris became an engineer and designed a spectacular wheel that would carry people over the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893.

“George must be out of his mind,” thought other engineers when they saw that George intended for people to ride passenger cars attached to his giant wheel. The public wasn’t sure either. “Some people were terrified just looking at it. Others couldn’t wait to ride on it.”

Thousands did indeed ride the wheel on the first day. “One thrill was enough for some folks; others raced to the end of the ticket line for another ride.”

There are several ways to turn the exciting (and sometimes sad) story of George Ferris and his invention into a writing workshop.

1) Ask students what they would like to invent. • Write a request for money or supplies to create your invention. Explain what the invention does and why it is worth spending money to make it - especially someone else’s money. Write a persuasive essay or letter to a parent, a local business or even a big foundation.

2) Think about the people who had a chance to ride that very first Ferris wheel.• Would you have been terrified just looking at it? Or would you be first in line to ride on the Ferris wheel? Explain why (or draw a picture of yourself near or on the Ferris wheel).

3) George Ferris’ first wheel was moved from Chicago to St Louis for another world’s fair in 1904, but after that fair, there was “no new home for the wheel. It was destroyed with dynamite and sold for scrap.”• What do you think should have happened to the first Ferris wheel instead?

Important inventions often start with dreams. “As long as there are dreamers like George Ferris ready to make big plans, the world can look forward to wonderous new inventions like his.”

http://childrensbookguild.org/karen-leggett-abouraya

Have you seen a toy or gadget and thought, “I could make a better one than that!” That was exactly what George Ferris thought when he lay in the grass as a boy watching a waterwheel move.

“The boy watched, fascinated. Maybe there is another way to make a wheel go around, he thought.”

Betsy Harvey Kraft tells Ferris’ story in The Fantastic Ferris Wheel: The Story of Inventor George Ferris.

Indeed there was. Ferris became an engineer and designed a spectacular wheel that would carry people over the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893.

“George must be out of his mind,” thought other engineers when they saw that George intended for people to ride passenger cars attached to his giant wheel. The public wasn’t sure either. “Some people were terrified just looking at it. Others couldn’t wait to ride on it.”

Thousands did indeed ride the wheel on the first day. “One thrill was enough for some folks; others raced to the end of the ticket line for another ride.”

There are several ways to turn the exciting (and sometimes sad) story of George Ferris and his invention into a writing workshop.

1) Ask students what they would like to invent. • Write a request for money or supplies to create your invention. Explain what the invention does and why it is worth spending money to make it - especially someone else’s money. Write a persuasive essay or letter to a parent, a local business or even a big foundation.

2) Think about the people who had a chance to ride that very first Ferris wheel.• Would you have been terrified just looking at it? Or would you be first in line to ride on the Ferris wheel? Explain why (or draw a picture of yourself near or on the Ferris wheel).

3) George Ferris’ first wheel was moved from Chicago to St Louis for another world’s fair in 1904, but after that fair, there was “no new home for the wheel. It was destroyed with dynamite and sold for scrap.”• What do you think should have happened to the first Ferris wheel instead?

Important inventions often start with dreams. “As long as there are dreamers like George Ferris ready to make big plans, the world can look forward to wonderous new inventions like his.”

http://childrensbookguild.org/karen-leggett-abouraya

Published on February 29, 2016 14:00

February 22, 2016

LOTTERY WRITING PROMPTS

by Jacqueline Jules

Recently, I enjoyed Tammar Stein’s young adult novel, Spoils. When the book begins, Leni is a week away from her 18th birthday and the right to spend her million dollar trust fund as she chooses. Her father won the lottery seven years before and she is the only family member left with money from the big event. Leni’s parents spent their lottery winnings on a lavish lifestyle that has left them broke and living in a mansion, cringing at calls from creditors. Leni is emotionally torn. She feels she has a responsibility to her parents to help them financially but she would rather donate her money to a worthy cause. Leni’s dilemma would make a fascinating writing prompt for middle or high school students. With last month's 1.4 billion dollar PowerBall, many students have already considered what they might do with a lottery win, making this writing prompt an attractive one for reluctant writers.

Recently, I enjoyed Tammar Stein’s young adult novel, Spoils. When the book begins, Leni is a week away from her 18th birthday and the right to spend her million dollar trust fund as she chooses. Her father won the lottery seven years before and she is the only family member left with money from the big event. Leni’s parents spent their lottery winnings on a lavish lifestyle that has left them broke and living in a mansion, cringing at calls from creditors. Leni is emotionally torn. She feels she has a responsibility to her parents to help them financially but she would rather donate her money to a worthy cause. Leni’s dilemma would make a fascinating writing prompt for middle or high school students. With last month's 1.4 billion dollar PowerBall, many students have already considered what they might do with a lottery win, making this writing prompt an attractive one for reluctant writers.

What would you do if you won the lottery? Would you spend it only on yourself and/or your family?What items would you buy?Would you travel?Would you make investments? How would you choose what companies to invest in?Would you try to help others? If so, would you choose individuals or an organized charity?

Ask your students to do a freewrite about winning the lottery, recording every fun fantasy they have. Then ask them to revise after digging a little deeper with research into some of the issues mentioned in Spoils, such as how 70 % of lottery winners are broke after a few years. How friends, relatives, and strangers hound them for money. How many end up living much worse lives than before. Time Magazine ran an article January 12, 2016, “Here’s How Winning the Lottery Makes You Miserable.” On the same day, The Daily News ran “Curse of the lottery: Tragic stories of bigjackpot winners.”

Warning: Some of these news stories on winning the lottery are not for the faint-hearted. However, asking your students to write about the consequence of having a dream come true could produce some provocative narratives and spark interest from middle schoolers and high schoolers who never enjoyed writing before.

www.jacquelinejules.com

Recently, I enjoyed Tammar Stein’s young adult novel, Spoils. When the book begins, Leni is a week away from her 18th birthday and the right to spend her million dollar trust fund as she chooses. Her father won the lottery seven years before and she is the only family member left with money from the big event. Leni’s parents spent their lottery winnings on a lavish lifestyle that has left them broke and living in a mansion, cringing at calls from creditors. Leni is emotionally torn. She feels she has a responsibility to her parents to help them financially but she would rather donate her money to a worthy cause. Leni’s dilemma would make a fascinating writing prompt for middle or high school students. With last month's 1.4 billion dollar PowerBall, many students have already considered what they might do with a lottery win, making this writing prompt an attractive one for reluctant writers.

Recently, I enjoyed Tammar Stein’s young adult novel, Spoils. When the book begins, Leni is a week away from her 18th birthday and the right to spend her million dollar trust fund as she chooses. Her father won the lottery seven years before and she is the only family member left with money from the big event. Leni’s parents spent their lottery winnings on a lavish lifestyle that has left them broke and living in a mansion, cringing at calls from creditors. Leni is emotionally torn. She feels she has a responsibility to her parents to help them financially but she would rather donate her money to a worthy cause. Leni’s dilemma would make a fascinating writing prompt for middle or high school students. With last month's 1.4 billion dollar PowerBall, many students have already considered what they might do with a lottery win, making this writing prompt an attractive one for reluctant writers.What would you do if you won the lottery? Would you spend it only on yourself and/or your family?What items would you buy?Would you travel?Would you make investments? How would you choose what companies to invest in?Would you try to help others? If so, would you choose individuals or an organized charity?

Ask your students to do a freewrite about winning the lottery, recording every fun fantasy they have. Then ask them to revise after digging a little deeper with research into some of the issues mentioned in Spoils, such as how 70 % of lottery winners are broke after a few years. How friends, relatives, and strangers hound them for money. How many end up living much worse lives than before. Time Magazine ran an article January 12, 2016, “Here’s How Winning the Lottery Makes You Miserable.” On the same day, The Daily News ran “Curse of the lottery: Tragic stories of bigjackpot winners.”

Warning: Some of these news stories on winning the lottery are not for the faint-hearted. However, asking your students to write about the consequence of having a dream come true could produce some provocative narratives and spark interest from middle schoolers and high schoolers who never enjoyed writing before.

www.jacquelinejules.com

Published on February 22, 2016 14:00

February 15, 2016

COME ON, FEEL THE NOISE!

guest post by Nancy Viau

Kids love sound words, and onomatopoeia is often taught as early as kindergarten. Students know that onomatopoeia makes reading aloud fun, but do they know that they can use onomatopoeia in their writing now and for many years to come? Why not help them create an Onomatopoeia Resource List?

Encourage students to listen for the sounds in and around their classroom—the tick, tock of clock, hands clapping, fingers snapping, water splashing, shoes clacking, birds tweeting, etc. Name the onomatopoeia and begin your list as a class (tick, tock, clap, snap, splash, clack, tweet). Students copy the words in their writing journals, leaving plenty of room for additions.

Introduce Storm Song, one of my titles. Prepare for reading by asking students what sounds they hear during a storm, then read it straight through. Talk about what happens in the story and ask if the story contains any onomatopoeia. Have kids add these words to their lists.

Next, do the same thing with City Street Beat, my latest rhyming picture book. Like Storm Song, it’s filled with onomatopoeia. As you read it aloud, you’ll find that students have acquired quite an ear for sound words.

At this point, Onomatopoeia Resource Lists should contain approximately 100 words! Here’s a cool fact: My personal ORL has 402 words—YAY!

Extended Activities:

Come On, Write the Noise: Students imagine a noisy setting such as a city, pool, zoo, amusement park, airport, farm, pet store, or home. After brainstorming noises in pairs, they get those pencils TAPPING and use at least 10 sound words in a one-page story.

Come On, Spell the Noise: Add the word “onomatopoeia” to spelling tests. Getting 12 letters in perfect order is something to be proud of. WHOOT!

Come On, Find the Noise: Work with the school librarian and help kids ZIG and ZAG, SHUFFLE and ZOOM through the library to find titles that contain onomatopoeia.

Here are some helpful lists:https://www.goodreads.com/shelf/show/onomatopoeia

https://www.librarything.com/tag/onomatopoeia

BOOM! Your students understand the importance of onomatopoeia and now have a resource list to use, and add to, for the next decade.

Nancy Viau is the author of three picture books: City Street Beat, Look What I Can Do! and Storm Song, and two middle-grade novels: Samantha Hansen Has Rocks in Her Head and Just One Thing! (Fall 2016). In her interactive, energetic story hours, assembly programs, and writing workshops, Viau gets young readers rhyming and writing on the spot. She’s a Jersey girl with ties to both the country and the seashore, and finds inspiration in nature, travel, and her job as a librarian assistant. www.NancyViau.com

Nancy Viau is the author of three picture books: City Street Beat, Look What I Can Do! and Storm Song, and two middle-grade novels: Samantha Hansen Has Rocks in Her Head and Just One Thing! (Fall 2016). In her interactive, energetic story hours, assembly programs, and writing workshops, Viau gets young readers rhyming and writing on the spot. She’s a Jersey girl with ties to both the country and the seashore, and finds inspiration in nature, travel, and her job as a librarian assistant. www.NancyViau.com

Kids love sound words, and onomatopoeia is often taught as early as kindergarten. Students know that onomatopoeia makes reading aloud fun, but do they know that they can use onomatopoeia in their writing now and for many years to come? Why not help them create an Onomatopoeia Resource List?

Encourage students to listen for the sounds in and around their classroom—the tick, tock of clock, hands clapping, fingers snapping, water splashing, shoes clacking, birds tweeting, etc. Name the onomatopoeia and begin your list as a class (tick, tock, clap, snap, splash, clack, tweet). Students copy the words in their writing journals, leaving plenty of room for additions.

Introduce Storm Song, one of my titles. Prepare for reading by asking students what sounds they hear during a storm, then read it straight through. Talk about what happens in the story and ask if the story contains any onomatopoeia. Have kids add these words to their lists.

Next, do the same thing with City Street Beat, my latest rhyming picture book. Like Storm Song, it’s filled with onomatopoeia. As you read it aloud, you’ll find that students have acquired quite an ear for sound words.

At this point, Onomatopoeia Resource Lists should contain approximately 100 words! Here’s a cool fact: My personal ORL has 402 words—YAY!

Extended Activities:

Come On, Write the Noise: Students imagine a noisy setting such as a city, pool, zoo, amusement park, airport, farm, pet store, or home. After brainstorming noises in pairs, they get those pencils TAPPING and use at least 10 sound words in a one-page story.

Come On, Spell the Noise: Add the word “onomatopoeia” to spelling tests. Getting 12 letters in perfect order is something to be proud of. WHOOT!

Come On, Find the Noise: Work with the school librarian and help kids ZIG and ZAG, SHUFFLE and ZOOM through the library to find titles that contain onomatopoeia.

Here are some helpful lists:https://www.goodreads.com/shelf/show/onomatopoeia

https://www.librarything.com/tag/onomatopoeia

BOOM! Your students understand the importance of onomatopoeia and now have a resource list to use, and add to, for the next decade.

Nancy Viau is the author of three picture books: City Street Beat, Look What I Can Do! and Storm Song, and two middle-grade novels: Samantha Hansen Has Rocks in Her Head and Just One Thing! (Fall 2016). In her interactive, energetic story hours, assembly programs, and writing workshops, Viau gets young readers rhyming and writing on the spot. She’s a Jersey girl with ties to both the country and the seashore, and finds inspiration in nature, travel, and her job as a librarian assistant. www.NancyViau.com

Nancy Viau is the author of three picture books: City Street Beat, Look What I Can Do! and Storm Song, and two middle-grade novels: Samantha Hansen Has Rocks in Her Head and Just One Thing! (Fall 2016). In her interactive, energetic story hours, assembly programs, and writing workshops, Viau gets young readers rhyming and writing on the spot. She’s a Jersey girl with ties to both the country and the seashore, and finds inspiration in nature, travel, and her job as a librarian assistant. www.NancyViau.com

Published on February 15, 2016 14:00

February 8, 2016

INSPIRE YOUR STUDENTS WITH BLUE DOG

by Joan Waites

This past week, my young art students completed a project based on the Blue Dog paintings by the late artist George Rodrigue. After talking about the artist and looking at examples of his work, students were instructed to create their own version of a blue dog painting. The idea was not to copy the original work exactly, but to give their own dog a personality by using color choices, background design, and any accessories they wanted their dog to wear.

The paintings were completed on canvas paper with initial sketches done in pencil. Students then traced over their pencil lines with black oil pastel. Acrylic paint was used to fill in color, and as a final step, black acrylic ink was used to go over the oil pastel lines that may have been covered up in the painting process. Works like this could also be completed using basic supplies such as oil pastel, tempera paint, or using colored pencils and crayons.

There have been several books for children written by the artist featuring Blue Dog, including Why is Blue Dog Blue and Are You Blue Dog's Friend?

As a writing exercise to complement the art, ask students to write a short story featuring their blue dog character. Where does he/she live? Who are his/her owners? What does their dog like to do? Who are his friends, and the question that might reveal the most exciting part of the story…why is Blue Dog blue?

www.joanwaites.com

This past week, my young art students completed a project based on the Blue Dog paintings by the late artist George Rodrigue. After talking about the artist and looking at examples of his work, students were instructed to create their own version of a blue dog painting. The idea was not to copy the original work exactly, but to give their own dog a personality by using color choices, background design, and any accessories they wanted their dog to wear.

The paintings were completed on canvas paper with initial sketches done in pencil. Students then traced over their pencil lines with black oil pastel. Acrylic paint was used to fill in color, and as a final step, black acrylic ink was used to go over the oil pastel lines that may have been covered up in the painting process. Works like this could also be completed using basic supplies such as oil pastel, tempera paint, or using colored pencils and crayons.

There have been several books for children written by the artist featuring Blue Dog, including Why is Blue Dog Blue and Are You Blue Dog's Friend?

As a writing exercise to complement the art, ask students to write a short story featuring their blue dog character. Where does he/she live? Who are his/her owners? What does their dog like to do? Who are his friends, and the question that might reveal the most exciting part of the story…why is Blue Dog blue?

www.joanwaites.com

Published on February 08, 2016 14:00

Mary Quattlebaum's Blog

- Mary Quattlebaum's profile

- 22 followers

Mary Quattlebaum isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.