Adam Thierer's Blog, page 155

December 7, 2010

Milton Mueller on internet governance

On the podcast this week, Milton Mueller, Professor and Director of the Telecommunications Network Management Program at the Syracuse University School of Information Studies, discusses his new book, Networks and States: The Global Politics of Internet Governance. Mueller begins by talking about Wikileaks' recent leak of diplomatic cables, using the incident to elaborate on the meaning of internet governance. He notes the distinction between traditional centralized systems of authority and peer-produced, distributed governance that rules much of cyberspace. He also discusses global democracy, contradictions in cyber libertarian views, judicial checks and balances on the internet, and future issues in internet governance.

Related Links

"Mueller's Networks and States = Classical Liberalism for the Information Age", by Adam Thierer

"How to Discredit Net Neutrality", by Mueller

"'Networks and States' at the Internet Governance Forum", by Mueller

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we'd like to ask you to comment at the web page for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

December 6, 2010

Some thoughts on Cablegate

It's been surprising to me that none of my TLF colleagues has yet ventured a post about this latest WikiLeaks controversy. But perhaps it shouldn't be so surprising because the Cablegate case presents some very hard questions to which there are no easy answers. I'm not sure that I know myself exactly how I feel about every issue related to leaks. But to try to get some conversation going, and to try to pin down my own feelings, I thought I'd take a stab at writing down some thoughts.

Is it legitimate for states to keep secrets from their citizens? It's a good question, but not one I'm interested in addressing here. The fact is that they do keep secrets.

Should the disclosure of classified information be a criminal offense? Given state secrets, this is a bit of a moot question because a state's ability to keep a secret depends on it's ability to punish disclosure by anyone entrusted with secrets. If nothing else, someone so entrusted has likely made a promise not to disclose. (There should, of course, be whistleblower protections in place that make exceptions to the rule.)

Therefore, the interesting question is this: Should there be liability for third parties who publish disclosed information?

Something that I think is easily overlooked in the present controversy, thanks in part to the fixation on Julian Assange, is that Wikileaks is simply a publisher. It did not steal the documents it is now releasing.

Making publishers liable for the distribution of information is nothing new. For example, it is illegal to publish child pornography, even if the publisher was not involved in its creation. One justification for such a rule is the further harm visited upon victims by the continued publication of images of their abuse. So we can conceive of a scenario in which the publication of classified information by a third party could cause real harm to persons.

What would constitute sufficient harm to merit third-party liability for the publication of classified information? Well, one would certainly imagine that the threat of physical harm to operatives, informants or other persons would qualify. Short of that, it's difficult to imagine the type of information that would not be protected by the freedoms of speech and the press upheld in cases like Near v. Minnesota and New York Times Co. v U.S. Certainly political embarrassment or the uncovering of corruption should not apply. To quote President Obama:

The Government should not keep information confidential merely because public officials might be embarrassed by disclosure, because errors and failures might be revealed, or because of speculative or abstract fears. Nondisclosure should never be based on an effort to protect the personal interests of Government officials at the expense of those they are supposed to serve.

Now, to the extent that there is some sort of third party liability for the publication of classified information, we must ensure that it is accompanied by due process. Several online intermediaries that provide WikiLeaks the tools it uses to publish, including Amazon, have booted Wikileaks off their platforms. Amazon acted after a call from Sen. Lieberman's office. The threats implicit in political pressure has no place in a free society.

Despite the foregoing discussion of the legalities of leaks and third-party publication, the practical effect is that it is nearly impossible to completely eliminating any particular bit of information from the Internet. Peer-to-peer distribution, mass-mirroring, and even the possible forking of the DNS root stand in the way of censorship. That is a reality that transcends any normative questions about the WikiLeaks case.

If it can't censor after the fact, what can government do? First, it can reevaluate how much information it is classifying as secret. The more classified information there is, the more there is available to leak; the more loosely one applies the "secret" stamp, the less meaning it has. Again, that is a positive statement, not a normative one. Second, government can shore up it's security protocols. If we are to believe the reports in the papers, nearly 3 million persons with clearance had access to the leaked cables. Tightening security will no doubt have an effect on information-sharing, but that's an inevitable trade-off that my first recommendation will make easier to asses.

Finally, to the extent that the U.S. government's policy is to attempt to censor embarrassing disclosures about its operations, it would be contradicting its own foreign policy of internet freedom. And if in fact information can only be marginally suppressed, then I hope the U.S. recognizes that relative to other nations, especially authoritarian ones, it might have more to gain than lose from internet freedom.

Location-Based Services: A Privacy Check-In

The ACLU of Northern California says it's time for a privacy check-in on location based-services. Their handy chart compares several of the most popular location-based services along a number of dimensions.

Little of what they examine has to do with civil liberties—cough, cough, ahem (this is a favorite critique of mine for my ACLU friends)—but the report does find that five out of six location-based providers are unclear about whether they require a warrant before handing information over to the government. Facebook is the winner here. Yelp, Foursquare, Gowalla, Loopt, and Twitter are unclear about whether they protect your location data from government prying.

Social Media Replacing Traditional News

December 3, 2010

Do Not Track– a Single "Nuclear" Response for a Diversity of Choices

"The do-not-track system could put an end to the technological 'arms race' between tracking companies and people who seek not to be monitored." – David Vladeck, FTC

David Vladeck is right. The Do Not Track system would put an end to the technological "arms race" – but that's not a good thing. Instead, its the nuclear option that will halt ongoing industry innovation and consumer welfare.

This has been unofficial privacy week in Washington, DC. Wednesday saw the release of the FTC's privacy report. Yesterday was the House Commerce Committee hearing; phrased in the form of a question, the tile of the hearing was a bit presumptuous: "Do-Not-Track Legislation: Is Now the Right Time?" And today, NetChoice responds with why the answer to that question should be No.

Do Not Track is a Blunt Response, Not an Informed Choice

The FTC's report calls for a "uniform and comprehensive" way for consumers to decide whether they want their activities tracked. The Commission points to a Do Not Track system consisting of browser settings that would be respected by web tracking services. A user could select one setting in Firefox, for example, to opt out of all tracking online. The FTC wrongly calls this "universal choice."

Really, it's a universal response. It's a single response to an overly-simplified set of choices we encounter on the web. This single response means that tracking for the purpose of tailored advertising is either "on" or "off." There is no middle setting. But it is the "middle" where we want consumers to be. The middle setting would represent an educated setting where consumers understand the tradeoffs of interest-based advertising – in return for tracking your preferences and using them to target ads to you, you get free content/services. But an on/off switch is too blunt and not, err, targeted enough. There is no incentive for consumers to learn about the positives, they'll only fear the worst-case scenarios and will opt-out. In return they'll also opt-out of the benefits. [more on the "middle" below].

Do Not Track is nothing like Do Not Call

One of the fallacies about Do Not Track is that it would simply be like Do Not Call. But buyer beware: Do Not Compare the Two – they are nothing alike. As the IAB states in its analysis, there are fundamental technical differences:

Phone calls consist of one-to-one connections and are easily managed because each phone is identified by a consistent phone number. In contrast, the Internet is comprised of millions of interconnected websites, networks and computers—a literal ecosystem, all built upon the flow of different types of data. To create a Do Not Track program would require reengineering the Internet's architecture.

Moreover, there are immense cost-benefit differences, too. Telemarketing is marketing, nothing transformational about that. Tracking is about marketing too, but it's also much more: content personalization. As Fred Wilson described in yesterday's New York Times debate, "[t]racking is the technology behind some of the most powerful personalization technologies on the Web. A Web without tracking technology would be so much worse for users and consumers."

The "Middle Ground" is the Self Regulatory Approach Already Underway

Underlying this entire debate, and the disconnect between the benefits of tracking along with its costs, is the need for industry transparency and consumer education. Increasing transparency and promoting education would place the online industry squarely in the sweet spot, the "middle ground" where consumers are presented with the appropriate information to make informed decisions.

Thankfully, this process is already underway. It's the appropriately named Self Regulatory Program for Online Advertising. Central to it is the Advertising Option Icon, which allows consumers to understand why it is they received certain targeted ads and to opt-out of future ads. It's a just-in-time approach the kind of teachable moments that will truly educate and inform the meaning behind the choice.

The icon has only recently been activated, and the mechanisms to hold companies accountable will go live early in 2011. Let's wait for this industry-led initiative to take hold before we talk about more extreme Do Not Track measures.

Simple responses don't work for complex issues. That's why we see a simple "do not track" response as failing both online consumers and industry. Instead, let's encourage the "middle" ground here of tailored responses for diverse forms of information sharing. It's an arms race we want to encourage, as companies compete based on privacy policies and new technological innovation. Admittedly, throwing hand grenades is harder than dropping bombs, but innovation and consumer welfare will be rewarded in the long run.

Some Questions for Rep. Markey Regarding His New Kids' Privacy Bill

As part of what Politico's Tony Romm calls this week's "all-out online privacy blitzkrieg," Rep. Ed Markey (D-Mass) announced he would be proposing legislation aimed at better protecting kids from the supposed evils of online "tracking" and marketing. Apparently, Rep. Markey's effort will build on the "Do Not Track" proposal that is garnering so much attention this week.

Lost in the smoke surrounding that privacy blitzkrieg is an important distinction between these two proposals: There is a very big difference between re-engineering browsers and websites to comply with a "Do Not Track" mandate and a new regulatory scheme aimed at identifying the ages or identities of individuals using certain online sites or services. Namely, the latter likely necessitates some sort of mandatory age verification or online authentication regime for the Internet.

Let's take a step back for some context. Markey helped author the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) of 1998, which dealt with the collection of information for kids under 13 online. But COPPA wasn't a strict age verification or online authentication regime for the Internet. Instead, COPPA mandated a "verifiable parental consent" regime which the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) later enforced using a so-called "sliding scale" approach. Essentially, sites that are "directed at" kids under 13 are supposed to get parental consent using a variety of mechanisms (credit cards, sign and fax forms, phone calls, etc) before any collection of information takes place. Of course, there are some devilish details here regarding what counts as "directed at" or "collection," but the crucial point here is that COPPA does not require the formal authentication of web surfer identities or ages — whether they kids or parents.

So, the really tricky question here is how one goes about expanding the COPPA regulatory regime without stumbling into the legal thicket that tied up the Child Online Protection Act (COPA) of 1998, a law which did mandate such an authentication regime and, as a result, witnessed a grueling decade-long legal battle over its constitutionality. Ultimately, the courts rejected COPA as inconsistent with America's tradition of anonymous speech, something central to our evolution as a democracy, pre-dating even the First Amendment that protects it from government interference. Thus, we have, at least for now, closed the book on COPA. But are we about to re-open it with COPPA expansion a la the forthcoming Markey bill?

At yesterday's House Energy & Commerce hearing on "Do Not Track" where he announced his intention to drop legislation, Rep. Markey didn't offer concrete details about how his bill would work, but he did go out of his way to praise the work of Common Sense Media (CSM) on this front. This implies his plan will be in line with what CSM has already advocated. As I noted in this essay in July, CSM recently submitted a filing to the FTC advocating expanding COPPA's age scope to cover all kids under 18 as well as opt-in mandates for the collection and use of any "personal information" or "behavioral marketing."

As I pointed out in that earlier essay, as well as in this beefy paper with Berin Szoka, "COPPA 2.0: The New Battle over Privacy, Age Verification, Online Safety & Free Speech," there are many profound questions raised by any proposal to expand COPPA along the lines that Common Sense Media and presumably now Rep. Markey suggest. Here are a few questions that privacy advocates and policymakers need to consider before heading down this path:

What is the supposed harm that requires such a significant expansion of Internet regulation? Why the need for a massive expansion of federal regulation in this area? CSM never makes it clear in its FTC filing. Are there corresponding benefits to be considered? Aren't other values or principles at stake here?

What are the free speech implications of their proposals. Extending COPPA to cover older teens will require websites used by large numbers of adults to age verify all users. This raises the same First Amendment concerns about government interference with anonymous communication that caused COPA to be struck down by the courts as unconstitutional. Thus, another lengthy legal battle likely awaits.

Is it the case that — in the name of protecting privacy — this approach might demand a massive amount of additional information be collected to facilitate the regulatory regime? Expanded age verification mandates would mean more information has to be collected about kids and their parents, but also about adults who, after all, have to prove they aren't children! That means a honey pot of new information would be created and held by someone, potentially the government itself.

How would such a proposal cope with all the sites or services that allow voluntary sharing of personal information by children? In an era of widespread user-generated content, instant messaging, online gaming, and other forms of digital interaction, expanded verifiable parental consent requirements become a formidable regulatory problem.

Don't older teens have some speech rights? The Common Sense Media proposal implies that teens are utterly incapable of making decisions for themselves until the day they turn 18. Never mind that most U.S. states set their age of consent at 16 or 17, for example. These teens are people who we already allow to hold jobs and drive cars and who will shortly be in college and then eligible to vote and serve in our Armed Forces. Yet, the CSM approach would require "verifiable parental consent" before older teens could read or look at anything online.

What will the economic impact be of this mandate on smaller websites that cater to kids & teens? If expanded regulation crowds out smaller start-ups, the resulting level of creativity and innovation in this market will suffer. Thus, COPPA expansion could lead to unnecessary industry consolidation as smaller operators are forced to sell to bigger player who can cover regulatory compliance costs.

What's the potential cost to consumers / parents? Expanding verifiable parental consent requirements will no doubt burden the creators or various sites and services, but those costs will ultimately be borne by the public when they are passed along in the form of a fee for services, many of which were previously free of charge.

Aren't there better, less burdensome, ways to protect kids' privacy online? There are many beneficial steps being taken by site operators today that make kids safer online. If we assume that COPPA is the most important approach to keeping kids safe online, we are making a huge mistake. COPPA is probably one of the least important things that keeps kids safe online. It's what sites do after kids get into their online communities that is really important because—guess what!—kids are going to get in to social networking communities and other sites. There are many important steps being taken by countless online sites and communities take to make sure they offer more safe and secure environments for kids. In particular, beyond basic parental controls, moderation and intervention efforts by site operators are increasing within social networking sites, virtual worlds, and many other sites to ensure that they offer such "well lit" online neighborhoods. We should be encouraging a lot more of that and working to find new "oversight and intervention" methods to deal with problems when they pop up. Common Sense Media has done a lot of great work on this front and should have focused on how those methods could be improved instead of how the create a more cumbersome, intrusive, expensive, and ultimately unworkable age verification regulatory regime for the Internet.

As Rep. Markey and his fellow policymakers move forward with any plan to expand COPPA, they should carefully weight these considerations against the supposed evils of online data collection, advertising, and marketing. It's certainly true that greater care must be taken by advertisers and marketers when dealing with kids, but education, user / parental empowerment, and industry self-regulation may be the better approach here.

December 2, 2010

On the Benefits of Web "Tracking"

There's a sharp piece by Fred Wilson in the New York Times today pointing out the benefits of online "tracking." It's part of a series of essays in one of their "Room for Debate" series about the FTC's new "Do Not Track" regulatory proposal. (Our own Jim Harper also has a good essay worth reading.)

In Wilson's essay, "Tracking Personalizes the Web," he argues:

"Tracking helps services like the Weather Channel give you the information you are looking for without having to enter a lot of data every time you use the service. Tracking can make sure you don't see the same news story twice.

Tracking is the technology behind some of the most powerful personalization technologies on the Web. A Web without tracking technology would be so much worse for users and consumers."

He's right, "tracking" makes personalization possible–and much more effective. But the really important point here is the one I made early today in my essay on "No-Cost Opt-Outs & Online Content & Culture": data collection and advertising drive the free online content, sites, and services we take for granted today. Personalization of all those things is great, but we might not have some (most?) of them at all without data collection and advertising, or we'd at least have fewer that were entirely gratis.

Free isn't really free, people!

No-Cost Opt-Outs & Online Content & Culture

In his essay today, "Go On, Opt Out. Just Don't Come Cryin' To Me …," John Battelle has some very sensible thinking on the "Do Not Track" idea and privacy regulation more generally:

Look, if you want to, you can put yourself on a "do not track" list in the Real World. As you walk around in our Real World, where small shopkeepers and Starbucks alike attempt to lure you into their stores, you can simply decide to ignore their come ons. You can refuse to get a grocery card, and forego the discounts they offer. You can forego the countless coupons, come ons, and catalogs that come through your newspaper, browser, or your community mailer, and if you work at it, you can even opt out through some specialized services (with more coming soon, if the FTC gets its way). And you can turn off your television (cause lord knows even the shows are trying to influence you now), and you can ignore your friends when they talk about the latest, coolest promotion that Verizon or ATT has pushed them through their cell phones. If folks insist on talking about stuff that might smack of someone selling you something, heck, you can start to dress like the Unabomber and withdraw entirely from our obviously commercial culture. You might look weird, but at least folks will leave you alone. And if you do, your world will either be better, or it will suck more. Your call.

But don't come crying to me when you realize that in opting out of our marketing-driven world, you've also opted out of, well, a pretty important part of our ongoing cultural conversation, one that, to my mind, is getting more authentic and transparent thanks to digital platforms. And, to my mind, you've also opted out of being a thinking person capable of filtering this stuff on your own, using that big ol' bean which God, or whoever you believe in, gave you in the first place. Life is a conversation, and part of it is commercial. We need to buy stuff, folks. And we need to sell stuff too.

Amen, brother. This is a point Berin Szoka and I have made repeatedly here in the past: The debate over privacy regulation is fundamentally tied up with the future of online content and culture. The idea of a cost-free opt-out model for the all online data collection / advertising may sound seductive to some, but we must take into account the opportunity costs of regulation. The real world is full of trade-offs and, despite what the Federal Trade Commission seems to think, there is no such thing as a free lunch.

Correcting Herb Kohl (& Kayak & Bing Travel) on Google/ITA

Today comes news that Senator Kohl has sent a letter to the DOJ urging "careful review" of the proposed Google/ITA merger. Underlying his concerns (or rather the "concerns raised by a number of industry participants and consumer advocates that I believe warrant careful review") is this:

Many of ITA's customers believe that access to ITA's technology is critical to competition in online air travel search because it cannot be matched by other players in the travel search industry. They claim that ITA's superior access to information and superior technology enables it to provide faster and better results to consumers. As a result, some of these industry participants and independent experts fear that the current high level of competition among online travel agents and metasearch providers could be undermined if Google were to acquire ITA and start its own OTA or metasearch service. If this were to happen, they argue, consumers would lose the benefits of a robustly competitive online air travel market.

For several reasons, these complaints are without merit and a challenge to the Google/ITA merger would be premature at best—and a costly mistake at worst. The high-tech market is innovative and dynamic. Goods and services that were once inconceivable are now indispensable, and competition has improved the quality of technology while driving down its costs. But as the market continues to change, antitrust interventions are stuck using a static regulatory framework. As the government develops a strategy for regulating competition in the digital marketplace, it must tread carefully—excessive intervention will stifle innovation, harm consumers, and prevent growth. And given the link between innovation and economic growth, the stakes of "getting it right" are high. The individual nature of every decision, however, makes errors in antitrust enforcement inevitable. Some conduct that is bad for competition will be allowed to go on while some conduct that is good for competition will be blocked by intervention.

But prosecuting pro-competitive conduct is almost certainly more costly than mistakenly allowing anticompetitive conduct because mechanisms are in place to mitigate the latter but not the former. The cost of erroneous intervention is the loss to consumers directly and a deterrent effect on innovation—for fear of intervention, companies may not take large risks. Meanwhile, allowing conduct to persist amidst uncertainty allows the potential benefits of conduct to materialize while maintaining checks against practices that are bad for consumers: both the competitive marketplace and future enforcers have the power to mitigate specific anticompetitive outcomes that may arise. Unfortunately, current antitrust enforcement—abetted by influential congressmen like Senator Kohl—is more, rather than less, aggressive against innovative companies in high-tech industries. This aggression threatens to stifle growth and deter future innovation in a market with incredible potential.

Google has become a primary target of this scrutiny, and the company's proposed acquisition of ITA, a software company that compiles and processes travel data, is a good example of aggressive scrutiny threatening to stifle growth.

Google's acquisition of ITA is a straightforward merger where one company has decided to purchase another outright (instead of merely purchasing its services through contract). There are good reasons for integration. Most notably, Google gets to exercise direct control over ITA's talented engineers if it owns ITA—influence that it would not have if the company simply signed a contract with ITA. If Google is correct that it can manage ITA's resources better than ITA's current management, then integration makes sense and is valuable for consumers.

The primary concern raised over Google's proposed acquisition of ITA is that acquisition would "leverage" Google's alleged dominance into another market—the online travel search market—and permit Google to prevent its competitors from accessing ITA's high-quality analysis of flights and fares. There are a few problems with this.

First, ITA does not provide or own the underlying data (this comes from the airlines themselves); rather it works only to analyze and process it—processing that other companies can and do undertake. It may have developed superior technology to engage in this processing, but that is precisely why it (and consumers) should not be penalized by its competitors' efforts to hamstring it. Remember—although most of the hand-wringing surrounding this deal concerns Google, it is first and foremost the innovative entrepreneurs at ITA who would be prevented from capitalizing on their success if the deal is stopped.

Second, it is hard to see why, under the facts as alleged by the deal's naysayers, consumers would be worse off if Google owns ITA than if ITA stands on its own. The claims seem to turn on ITA's indispensability to the online travel industry. But if ITA is so indispensable—if it possesses such market power, in other words—it's hard to see how its incentives to capitalize on that market power would change simply by virtue of a change in its management. Either ITA possesses market power and is already taking advantage of it (or else its managers are leaving money on the table and it most certainly should be taken over by another set of managers) or else it does not actually possess this market power and its combination with Google, even if Google were to keep all of ITA's technology for itself, will do little to harm the rest of the industry as its competitors step up and step in to take its place.

Third and related to these is the simple repugnance of hamstringing successful entrepreneurs because of the exhortations of their competitors, and the implication that a successful company's work product (like ITA's "superior technology") must be rendered widely-available, by government force if necessary.

Meanwhile, Google does not seem to have any interest in selling airline tickets or making airline reservations (just as it doesn't sell the retail goods one can search for using its site). Instead, its interest is in providing its users easy access to airline flight and pricing data and giving online travel agencies the ability to bid on the sale of tickets to Google users looking to buy. The availability of this information via Google search will lower search costs for consumers and the expected bidding should increase competition and drive down travel costs for consumers. It is easy to see why companies like Kayak and Bing Travel and Expedia and Travelocity might be unhappy about this, but far more difficult to see how their woes should be a problem for the antitrust enforcers (or Congress, for that matter).

The point is not that we know that Google—or any other high-tech company's—conduct is pro-competitive, but rather that the very uncertainty surrounding it counsels caution, not aggression. As the technology, usage and market structure change, so do the strategies of the various businesses that build up around them. These new strategies present unknown and unprecedented challenges to regulators, and these new challenges call for a deferential approach. New conduct is not necessarily anticompetitive conduct, and if our antitrust regulation does not accept this, we all lose.

[Cross-posted at Truth on the Market]

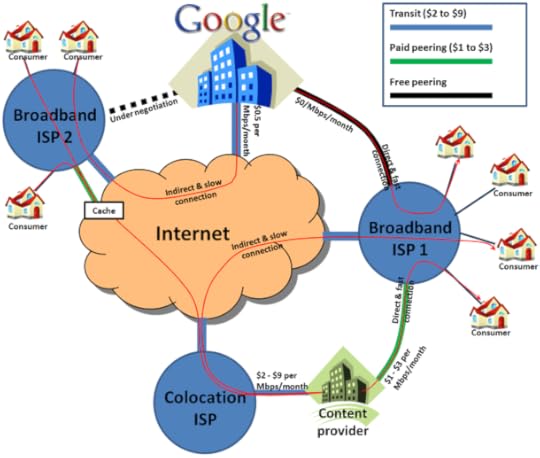

Buzz Out Loud's Epic Misunderstanding of Peering

I love listening to podcasts, yet I'm increasingly disappointed with popular tech news podcasts like CNET's Buzz Out Loud, which despite being staffed by tech journalists, consistently fail to grasp the basic economics of the Net. The latest case of this arose on Episode 1360 of "BOL," which took on the recent dispute between Comcast and Level3 over their peering agreement.

I love listening to podcasts, yet I'm increasingly disappointed with popular tech news podcasts like CNET's Buzz Out Loud, which despite being staffed by tech journalists, consistently fail to grasp the basic economics of the Net. The latest case of this arose on Episode 1360 of "BOL," which took on the recent dispute between Comcast and Level3 over their peering agreement.

To provide some background, Comcast and Level3 have had a standard peering agreement for years, meaning the balance of incoming and outgoing traffic on either side is so similar that the two have simply agreed to exchange data without exchanging any dollars.

In the past, Comcast and Level3 had a different arrangement. Comcast paid Level3 for access to their network in a "transit" agreement. This sort of agreement made sense at the time because Comcast was sending a lot more traffic over Level3′s network than it was taking in from Level3, hence it was a net consumer of bandwidth and was therefore treated by Level3 as a customer, rather than a peer.

Now, the tables have turned thanks to Level3 taking on the huge tasks of delivering Netflix streaming video, which takes an impressive amount of bandwidth—up to 20% of US peak traffic, according to CNET. So, logic and economics compel Comcast to start charging Level3, as Level3 is now the net consumer.

None of this background was understand by the folks at Buzz Out Loud, which probably explains why the hosts acted as though this peering dispute was a sign of the coming Internet apocalypse, decrying the action on the podcast and summarizing their feelings on the action in the episode's show notes by stating:

We break down the Level 3 and Comcast battle–no matter how you slice it, it's still very, very, VERY bad for the Web.

No, it's really, really, REALLY not.In fact, Comcast has actually been rather nice to Level3, according to Nate Anderson at Arstechnica:

Comcast "was able to scramble and provide Level 3 with six ports (at no charge) that were, by chance, available and not budgeted and forecasted for Comcast's wholesale commercial customers."

Anderson goes on to explain that Comcast then had to consider how this affected their agreement with Level3:

After providing these six additional ports, Comcast concluded that the existing settlement-free peering agreement with Level 3 was still (barely) valid, but if Level 3 really wanted another 21 to 24 ports, this was simply too much traffic. Level 3 would have to pay for those ports like any commercial paid peering customer.

To sum up, the two companies used to be exchanging bits at a roughly one-to-one ratio, that ratio has changed, so therefore one is charging the other for delivering some bits. Simple, right?

Yet somehow Buzz Out Loud has managed to turn this mundane non-news into a Chicken Little story and they even went so far as to suggest that Comcast may be scheming shut off Netflix traffic entirely in order to favor their own content, especially now that they're in the process of merging with NBC. To say that this is a baseless theory is an understatement.

Buzz Out Loud often ducks criticism by noting that they're just a podcast, that they're reporting on "buzz" not hard facts, and that they're really supposed to be entertaining. Fine, but if BOL is really supposed to be the Daily Show of tech podcasts, then they shouldn't make grand pronouncements on what's good or bad for the web, especially when the basic facts of a given situation aren't understood.

But I'm sure this isn't the last net neutrality doomsday scenario that Buzz Out Loud will concoct out of something humdrum. This sort of thing makes me wonder how much of the current debate on neutrality is grounded in a solid understanding of the underlying principles of the Net and how much is based on this sort of misinformed, ignorant, lazy "journalism."

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower