Adam Thierer's Blog, page 154

December 14, 2010

At FCC's "Generation Mobile" Event, the Kids Speak Plainly & Pointedly

At today's FCC "Generation Mobile" forum — chock-full of online safety experts, company reps, Jane Lynch of the TV show Glee, and even Chairman Genachowski himself — it was the kids that made the show about mobile technology worthwhile. On a panel about generation mobile, here are a few of the statements we heard from high school kids:

At today's FCC "Generation Mobile" forum — chock-full of online safety experts, company reps, Jane Lynch of the TV show Glee, and even Chairman Genachowski himself — it was the kids that made the show about mobile technology worthwhile. On a panel about generation mobile, here are a few of the statements we heard from high school kids:

"Don't just take the phone away."

"When parents snoop too much, it's a privacy invasion."

"We'll listen more if you present us with concrete evidence for behavioral restrictions."

These are the kinds of arguments tech policy advocates make, only we would have said them in our unique brand of policy speak:

Don't regulate the technology, regulate bad behavior.

Privacy is important and governments/companies must respect the privacy interests of their citizens/customers.

Policymakers should collect sufficient data and analysis before introducing new legislation

Policy geek speak aside, here are some interesting facts we heard about teen use of mobile technology:

According to Genachowski, 80% of fatal teen driving accidents are caused by distracted driving

According to Amanda Lenhart of Pew, 15% of kids have received a sext message; only 4% have sent a sext

Also from Amanda, 62% of schools allow cell phones in the school, but not in the classroom. 12% permissively allow anywhere.

Adam Thierer reviews the year in technology policy

On the podcast this week, Adam Thierer, senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University in the Technology Policy Program, reviews the past year in technology policy and looks ahead to next year. Thierer first weighs in on net neutrality and upcoming FCC deliberations could that hatch a new regulatory regime for the internet. He then talks Google and antitrust, the proposed Comcast-NBC merger, and disputes between broadcasters and content providers. He also suggests that two issues — privacy and cyber security — will be at the forefront of tech policy debates in the coming year, pointing to support for do-not-track rules and to recent WikiLeaks and state secrets drama as momentum behind the respective issues.

Related Links

"The 5-Part Case against Net Neutrality Regulation", by Thierer

"The 10 Most Important Info-Tech Policy Books of 2010″, by Thierer

"Online Privacy Regulation:

Likely More Complicated (And Costlier) Than Imagined", by Thierer

"And so the IP & Porn Wars Give Way to the Privacy & Cybersecurity Wars", by Thierer

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we'd like to ask you to comment at the web page for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

December 13, 2010

What Cablegate tells us about cyber-conservatism

Over a year ago Adam Thierer and Berin Szoka penned an essay seeking to define the contours of cyber-libertarianism, and they drew a contrast with the digital commons movement, part of what they called "cyber-collectivism." They were criticized, however, for not drawing a similar contrast to "cyber-conservatism." The reason they didn't do this, Adam explained, was because they didn't "think there really is a coherent 'cyber-conservative' movement out there the same way we see a rising 'Digital Commons' movement." I think the reaction to Cablegate might be allowing us to see the outlines of cyber-conservatism a bit better.

Over a year ago Adam Thierer and Berin Szoka penned an essay seeking to define the contours of cyber-libertarianism, and they drew a contrast with the digital commons movement, part of what they called "cyber-collectivism." They were criticized, however, for not drawing a similar contrast to "cyber-conservatism." The reason they didn't do this, Adam explained, was because they didn't "think there really is a coherent 'cyber-conservative' movement out there the same way we see a rising 'Digital Commons' movement." I think the reaction to Cablegate might be allowing us to see the outlines of cyber-conservatism a bit better.

The most vocal and strident reaction against Wikileaks has come from folks we can identify as neocons. Aside from demanding that the U.S. hunt down Julian Assange, Charles Krauthammer wrote, "Putting U.S. secrets on the Internet, a medium of universal dissemination new in human history, requires a reconceptualization of sabotage and espionage — and the laws to punish and prevent them." Meanwhile Marc Thiessen, ignoring the distributed nature of WikiLeaks, called for the U.S. to "rally a coalition of the willing to defeat WikiLeaks by shutting down its servers and cutting off its finances." And William Kristol, for his part, asked rhetorically, "Why can't we disrupt and destroy WikiLeaks in both cyberspace and physical space, to the extent possible? Why can't we warn others of repercussions from assisting this criminal enterprise hostile to the United States?"

I won't say there's a fully developed theory of internet policy in these statements, but you can definitely see a rejection of an unregulated internet, not to mention of internet exceptionalism. Information control in the name of security, they seem to argue, is more than justified. And despite his technical cluelessness, Marc Thiessen does grasp that pressuring internet intermediaries, like Amazon and PayPal, is an important way to control information.

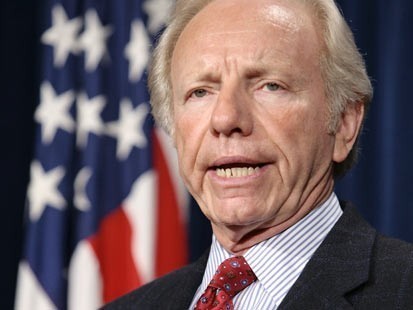

Joe Lieberman, often associated with neocon sensibilities, has led the charge to apply just such political pressure. As a result, some have pointed out how ironic it is that Sen. Lieberman is a founding member of the congressional Global Internet Freedom Caucus. (John McCain is also a founding member.) But maybe that shouldn't be so surprising.

In his forthcoming book, The Net Delusion, Evgeny Morozov talks about the neocons' embrace of the cause of internet freedom as a cheap and easy way of extending the "freedom agenda" of exporting democracy. In the book, Morozov coins the "cyber-con" moniker and points out that the first big event of the George W. Bush Institute (headed by former BBG Chairman and Undersecretary of State for Public Diplomacy James Glassman) was a conference on internet freedom in support of "cyber-dissidents" under authoritarian regimes. He also points out that many neocons have taken up the cause of the Falun Gong and have supported their campaign of cyber-resistance in China, sometimes with U.S. funding.

These contradictory views are problematic for a coherent cyber-conservative position, and to the extent that cyber-conservatism does develop into a unified vision, they'll have to deal with this problem. I can imagine, though, that if you believe in American exceptionalism and national greatness, these two viewpoints can be reconciled.

Also this week, another edge of cyber-conservatism's contours peeked through in an article Jim DeLong wrote for the American Enterprise Institute endorsing the Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeits Act (COICA). The bottom line of that piece is that there are limits to free speech, and protecting intellectual property is one of them, so allowing the DOJ to force intermediaries to act against suspected pirates is legitimate.

The internet is a means of communications, and communications is speech. Regulating the internet is regulating speech. I noted in my previous post on Cablegate that there are arguably legitimate reasons to limit speech, and I gave the example of child pornography (an example with which cyber-conservatives no doubt agree). Cyber-conservtaives, it seems, would add to that list national security and the protection of intellectual property rights. Others, generally from the Left, would add privacy and human dignity to the list. According to Adam and Berin, together the ideas of information control from the cyber Left and Right form "cyber-collectivism," which they define as "the general belief that cyber-choices should be guided by the State or an elite class according to some amorphous 'general will' or 'public interest,'" and to which cyber-libertarianism stands in contrast.

An aside: I'm not crazy about the "collectivist" label. Wiktionary defines "collectivism" as "an economic system in which the means of production and distribution are owned and controlled by the people collectively." A much better definition of "collectivism" for what Adam and Berin have in mind comes from the Concise OED: "the practice or principle of giving the group priority over each individual in it." To my mind, however, the fact is that the word "collectivism" is too wrapped up with the former definition to be very useful. And if you're including information control in the name of intellectual property protection in the definition, then I'm not sure collectivism is the word I'd use. What's a better label? I'm not sure, but off the top of my head, how about simply "statist"?

The tricky thing about cyber-libertarianism is that, at least as I would define it, it is not categorically opposed to information control, and it's important that we coherently articulate the contours of our own ideology. To me, libertarians simply have a narrower view of what information control is desirable, with harm to individuals as the relevant standard. They also prefer individual choices and self-regulation to state control. And to the extent that state control is unavoidable, they want to ensure robust due process and protection of individual liberties. I hope to flesh out these ideas some more in future posts.

December 12, 2010

Dynamic Pricing: The Unconcerning Scourge

Deep in this Washington Post story on dynamic pricing—prices that change based on what online retailers know or guess about individual customers—come these lines:

[A]s much as retailers try to foil bargain shoppers, consumers do hold the upper hand online. Dynamic pricing is easy to counteract. Search multiple sites – including ones that collect prices from across the Internet as well as the sites themselves. Run searches on more than one browser, including one which you have erased cookies. Leave items in a shopping cart for a few days to gin up discount offers.

That makes the rest of the story, and wafting consumer protection concerns with dynamic pricing, a little humdrum. Indeed, it belies the headline: "How Online Retailers Stay a Step Ahead of Comparison Shoppers."

Even better advice—certainly the simplest—is: Don't buy what you can't afford. That is serious consumer protection.

December 7, 2010

Tracking and Trade-Offs

While I harbor plenty of doubts about the wisdom or practicability of Do Not Track legislation, I have to cop to sharing one element of Nick Carr's unease with the type of argument we often see Adam and Berin make with respect to behavioral tracking here. As a practical matter, someone who is reasonably informed about the scope of online monitoring and moderately technically savvy already has an array of tools available to "opt out" of tracking. I keep my browsers updated, reject third party cookies and empty the jar between sessions, block Flash by default, and only allow Javascript from explicitly whitelisted sites. This isn't a perfect solution, to be sure, but it's a decent barrier against most of the common tracking mechanisms that interferes minimally with the browsing experience. (Even I am not quite zealous enough to keep Tor on for routine browsing.) Many of us point to these tools as evidence that consumers have the ability to protect their privacy, and argue that education and promotion of PETs is a better way of dealing with online privacy threats. Sometimes this is coupled with the claim that failure to adopt these tools more widely just goes to show that, whatever they might tell pollsters about an abstract desire for privacy, in practice most people don't actually care enough about it to undergo even mild inconvenience.

That sort of argument seems to me to be very strongly in tension with the claim that some kind of streamlined or legally enforceable "Do Not Track" option will spell doom for free online content as users begin to opt-out en masse. (Presumably, of course, The New York Times can just have a landing page that says "subscribe or enable tracking to view the full article.") If you think an effective opt-out mechanism, included by default in the major browsers, would prompt such massive defection that behavioral advertising would be significantly undermined as a revenue model, logically you have to believe that there are very large numbers of people who would opt out if it were reasonably simple to do so, but aren't quite geeky enough to go hunting down browser plug-ins and navigating cookie settings. And this, as I say, makes me a bit uneasy. Because the hidden premise here, it seems, must be that behavioral advertising is so important to supplying this public good of free content that we had better be really glad that the average, casual Web user doesn't understand how pervasive tracking is or how to enable more private browsing, because if they could do this easily, so many people would make that choice that it would kill the revenue model. So while, of course, Adam never says anything like "invisible tradeoffs are better than visible ones," I don't understand how the argument is supposed to go through without the tacit assumption that if individuals have a sufficiently frictionless mechanism for making the tradeoff themselves, too many people will get it "wrong," making the relative "invisibility" of tracking (and the complexity of blocking it in all its forms) a kind of lucky feature.

There are, of course, plenty of other reasons for favoring self-help technological solutions to regulatory ones. But as between these two types of arguments, I think you probably do have to pick one or the other.

And so the IP & Porn Wars Give Way to the Privacy & Cybersecurity Wars

Every once and awhile it's worth taking a step back and looking at the long view of how Internet policy developments have unfolded and consider where they might be heading next. We've reached such a moment as it pertains to efforts to police the Internet for copyright piracy, objectionable online content, privacy violations, and cybersecurity. We're at an interesting crossroads in this regard since the prospects for successful cracking down on copyright piracy and pornography appear grim. Seemingly every effort that has been tried has failed. The Net is awash in online porn and pirated content. I am not expressing a normative position on this, rather, I'm just stating what now seems to be commonly accepted fact.

Every once and awhile it's worth taking a step back and looking at the long view of how Internet policy developments have unfolded and consider where they might be heading next. We've reached such a moment as it pertains to efforts to police the Internet for copyright piracy, objectionable online content, privacy violations, and cybersecurity. We're at an interesting crossroads in this regard since the prospects for successful cracking down on copyright piracy and pornography appear grim. Seemingly every effort that has been tried has failed. The Net is awash in online porn and pirated content. I am not expressing a normative position on this, rather, I'm just stating what now seems to be commonly accepted fact.

In the meantime, the United States is in the process of creating new information control regimes and this time its access to personal information and cybersecurity that are the focus of regulatory efforts. The goal of the privacy-related regulatory efforts is to help Netizens better protect their privacy in online environments and stop the "arms race" of escalating technological capabilities. The goal of cybersecurity efforts is to make digital networks and systems more secure or, more profoundly as we see in the Wikileaks case, it is to bottle up state secrets.

These efforts are also likely to fail. Simply stated, it's a nightmare to bottle-up information once it's out there. It doesn't make a difference if that information we are seeking to control is copyrighted content, hate speech, dirty pictures, defamatory speech, secret diplomatic cables, or personal information. Information is the blood that runs through the veins of the Internet and once it's out it is pretty much Game Over. Commenting on the recent Wikileaks debacle over the release of diplomatic cables, Wall Street Journal columnist Daniel Henninger noted that "There is one certain fix for the WikiLeaks problem: Blow up the Internet. Short of that, there is no obvious answer." The same thing is increasingly true for these other types of information flows.

Now That's A Lot of Information

As I pointed out in my recent essay, "Privacy as an Information Control Regime," efforts to control information today are greatly complicated by problems associated with (1) convergence, (2) scale, (3) volume, and (4) unprecedented individual empowerment / user-generation of content. It's the volume problem that I want to spend a bit of time on here today.

As I noted in that previous essay, the sheer volume of media and communications activity taking place today greatly complicates regulatory efforts. In simple terms, there is just too much stuff for policymakers to police today relative to the past.

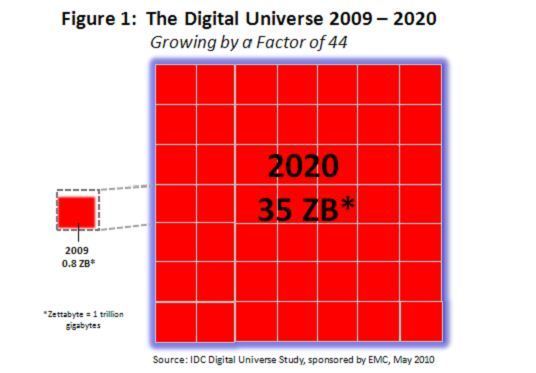

Let's put some hard numbers on this problem. IDC's 2009 report, "The Digital Universe Ahead — Are You Ready?" provides the following snapshot of the data deluge:

Last year, despite the global recession, the Digital Universe set a record. It grew by 62% to nearly 800,000 petabytes. A petabyte is a million gigabytes. Picture a stack of DVDs reaching from the earth to the moon and back.

This year, the Digital Universe will grow almost as fast to 1.2 million petabytes, or 1.2 zettabytes.

This explosive growth means that by 2020, our Digital Universe will be 44 TIMES AS BIG as it was in 2009. Our stack of DVDs would now reach halfway to Mars.

And here's a little something from the Global Information Industry Center's report on "How Much Information?":

In 2008, Americans consumed information for about 1.3 trillion hours, an average of almost 12 hours per day. Consumption totaled 3.6 zettabytes and 10,845 trillion words, corresponding to 100,500 words and 34 gigabytes for an average person on an average day. A zettabyte is 10 to the 21st power bytes, a million million gigabytes. These estimates are from an analysis of more than 20 different sources of information, from very old (newspapers and books) to very new (portable computer games, satellite radio, and Internet video). Information at work is not included.

(How about that caveat: information at work is not included!!)

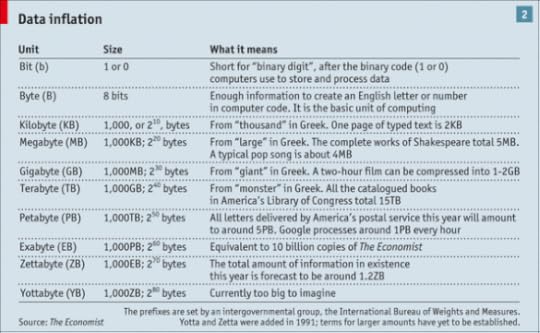

To put all these petabytes and zettabytes in some context, here's a chart that appeared in an Economist essay back in February entitled, "All Too Much: Monstrous Amounts of Data":

These are mind-boggling numbers. As the Economist chart suggests, it's hard to even fathom what "yottabytes" entails, but that's what's next.

Anyway, let's return to the privacy wars and think about the volume problem in that context. Today we're hearing proposals to regulate online services (advertising networks) or software (web browsers) to clamp down on the flow of information. The so-called "Do Not Track" mechanism is one potential solution that has been floated in the regard.

This reminds me of the illusive search for a "simple fix" or silver-bullet solution to online pornography. The PICS /ICRA experience is instructive in this regard. That would be the W3C's Platform for Internet Content Selection and Internet Content Rating Association. For a time, there was hope that voluntary metadata tagging and content labeling could be used to screen objectionable content on the Internet. But the sheer volume of material to be dealt with made that task almost impossible. The effort has been abandoned now. Of course, it's true that effort didn't have a government mandate behind it to encourage more widespread adoption, but even if it would have, does anyone really think all porn or other objectionable content would have been labeled and screened?

Similar problems await information control efforts in the privacy realm, even if a mandated Do Not Track mechanism required the re-engineering of web browser architecture. Those who think Do Not Track would slow the "arms race" in this arena are kidding themselves. If anything, a Do Not Track mandate will speed up that arms race. Take a look at how well The CAN SPAM Act worked in practice if you want another example.

Selective Morality

Now, let's pretend for a moment that I am wrong about all this in the privacy space and that the FTC and Congress somehow find a workable mechanism to control flows of personal information and can clamp down accordingly. Again, I don't believe it will happen, but if it did, doesn't that mean it's equally likely that the same mechanism would be used to crack down on speech, expression, copyrighted content, state information flows, or whatever else?

Perhaps that's not a bad thing from your perspective, but what I find entertaining about this debate is how the folks who support an aggressive information control regime for privacy purposes generally also oppose information control efforts as it pertains to speech, expression, copyright, or state secrets. There's a bit of selective morality at play here. When it comes to personal information, the attitude seems to be that we must 'pay any price, bear any burden,' even going so far as to property-tize personal information flows. In every other case, however, the attitude seems to be: Let information flow.

Regardless of one's disposition on these matters, my point here is more simple: the information will flow. Indeed, I think it is safe to say that there is a strong and growing negative correlation between the aggregate volume of data flowing across digital networks and the ability of policymakers to control those information flows. The recent Wikileaks release has made that new fact of life more evident to the world, but the ongoing IP wars might also hold some lessons for us in this regard.

Consider the thoughts of Sydney-based consultant Mark Pesce, who compares the two experiences. He writes:

We've been here before. This is 1999, the company is Napster, and the angry party is the recording industry. It took them a while to strangle the beast, but they did finally manage to choke all the life out of it – for all the good it did them. Within days after the death of Napster, Gnutella came around, and righted all the wrongs of Napster: decentralized where Napster was centralized; pervasive and increasingly invisible. Gnutella created the 'darknet' for filesharing which has permanently crippled the recording and film industries. The failure of Napster was the blueprint for Gnutella.

In exactly the same way – note for note – the failures of Wikileaks provide the blueprint for the systems which will follow it, and which will permanently leave the state and its actors neutered.

And it is likely a blueprint for what will happen in the privacy arena as well.

Conclusion

Again, I want to be clear that the point of this essay has not been to endorse or celebrate copyright piracy, widespread porn, privacy violations, release of state secrets, etc. We'll all have differences of opinions on these matters. But there's simply no getting around the fact that all these problems are all likely here to stay and, barring extreme crackdowns, it's very hard for me to imagine how government might reverse that tide.

In the extreme, I suppose we could follow the Chinese mode and firewall off digital networks, effectively nationalize ISPs, and then pay citizens to inform on each other about various transgressions. Or, we could impose punishing forms of liability on digital intermediaries — effectively deputizing online middlemen and making them servants of the State. But such extreme solutions would have nightmarish ramifications for the future of the Internet and digital communications networks. We have to ask ourselves how far we want to go to control information flows.

This is Earmark Transparency

This morning, a database of FY 2011 earmark requests was released by Taxpayers Against Earmarks, Taxpayers for Common Sense, and my own WashingtonWatch.com. With House Republicans generally eschewing earmarks this year, members of Congress and senators still sought over 39,000 earmarks, valued at over $130 billion dollars. Learn more on the relevant pages at Taxpayers for Common Sense, Taxpayers Against Earmarks, and WashingtonWatch.com.

This is transparency. The production of organized, machine-readable data has allowed these differing groups—an advocacy organization, a spending analysis group, and a "Web 2.0″ transparency site—to expand the discussion about earmarks. The data is available to any group, to the press, and to political scientists and researchers.

Earmarking is a questionable practice, and, anticipating public scrutiny, House and Senate Republicans have determined to eschew earmarks for the time being. But the earmark requests in this database are still very much "live." They could be approved in whatever spending legislation Congress passes for the 2011 fiscal year. They also tell us how our representatives acted before they got careful about earmarks.

Earmarks are a small corner of the federal policy process, of course, but when all legislation, budgeting, spending, and regulation has become more transparent—truly transparent, Senator Durbin—the public's oversight of Congress will be much, much better. As I noted at the December 2008 Cato Institute conference, "Just Give Us the Data," progressives believe that it would validate government programs and root out corruption. (That's fine—corruption and ongoing failure in federal programs are not preferable.) I believe that demand for government will drop. The average American family pays about $100 per day for the operation of the federal government currently. That's a lot.

Again, you can see how this data is in use, and you can use it yourself, by visiting Taxpayers for Common Sense, Taxpayers Against Earmarks, and WashingtonWatch.com. On the latter site, you can see a map of earmarks in your state and lists of earmarks by member of Congress and representative, then vote and comment on individual earmarks.

At considerable expense and effort, these sites have done what President Obama asked Congress to do in January. If earmarking is to continue, Congress could produce earmark data as a matter of course itself: The appropriations committees could take earmark requests online and immediately publish them, rather than using the opaque exchange of letters, phone calls, and—who knows—homing pigeons.

Congress should modernize and make itself more transparent. We're showing the way.

Does Wikileaks Have a First Amendment Case Against Joe Lieberman?

Amazon made headlines last week when it abruptly cut off service to Wikileaks, allegedly on the grounds that the site had violated Amazon's terms of acceptable use. However, Amazon's decision to terminate Wikileaks came less than 24 hours after Amazon received a phone call from Senate Homeland Security Committee staff (at the behest of Sen. Joe Lieberman) inquiring about the firm's relationship with Wikileaks. According to a report in The Guardian, Amazon's decision to terminate service to Wikileaks was a "reaction to heavy political pressure."

Amazon made headlines last week when it abruptly cut off service to Wikileaks, allegedly on the grounds that the site had violated Amazon's terms of acceptable use. However, Amazon's decision to terminate Wikileaks came less than 24 hours after Amazon received a phone call from Senate Homeland Security Committee staff (at the behest of Sen. Joe Lieberman) inquiring about the firm's relationship with Wikileaks. According to a report in The Guardian, Amazon's decision to terminate service to Wikileaks was a "reaction to heavy political pressure."

That's not all. Glenn Greenwald reported last week on Salon.com that another Internet company, Tableau Software, also decided to disable service to Wikileaks because of pressure from Joe Lieberman. Unlike Amazon, Tableau admitted that its decision was directly prompted by pressure from Lieberman. From Tableau's statement:

Our decision to remove the data from our servers came in response to a public request by Senator Joe Lieberman, who chairs the Senate Homeland Security Committee, when he called for organizations hosting WikiLeaks to terminate their relationship with the website.

It's difficult to see Joe Lieberman's "public request" as anything but a thinly-veiled threat. Case in point: In addition to his staffers' phone calls, Lieberman went on MSNBC last week, stating bluntly, "we've got to put pressure on any companies … which provide access to the Internet to Wikileaks."

As Chairman of the Senate Homeland Security Committee, Lieberman is in a uniquely powerful position to push for legislation that might harm private firms like Amazon. He can also hold Congressional hearings, which frequently turn into public spectacles and garner massive media coverage. A company's CEO enduring a congressional grilling on Capitol Hill can significantly impact that firm's public image — and, in some cases, its stock price as well. While no individual Senator has the power to enact laws, promulgate rules, or enforce regulations, a single crusading politician can arguably cause cognizable harm to any U.S. company that pushes back against "requests" to suppress unfavorable content.

How does this implicate the First Amendment? As EFF's Rainey Reitman and Marcia Hofmann pointed out on the DeepLinks blog, "The First Amendment to the Constitution guarantees freedom of expression against government encroachment — but that doesn't help if the censorship doesn't come from the government."

There's an important caveat to this point, however: When government coerces private entities into suppressing protected speech, it can trigger First Amendment scrutiny. Via my colleague (and First Amendment guru) Hans Bader:

In First Amendment cases, not only the party bound by a settlement or regulation, but also people whose speech or access to information is affected by it, have the right to challenge its restrictions. (See Korb v. Lehman, 919 F.2d 243 (4th Cir. 1990) (A private employee could sue a government official under the First Amendment for pressuring his private employer to fire him for his speech, even though private employers can voluntarily terminate employees for their speech when the employer is not operating under government pressure); and Truax v. Raich, 239 U.S. 33 (1916) (The Supreme Court held a state government liable under the Constitution for pressuring a private employer to fire a private employee based on his being an alien, even though his employer could have voluntarily dismissed him without violating any law)).

Of course, as an elected legislator, Lieberman enjoys fairly broad First Amendment rights to express his own political views. As the Supreme Court ruled in Bond v. Floyd:

The manifest function of the First Amendment in a representative government requires that legislators be given the widest latitude to express their views on issues of policy.

While Lieberman's tirade against Wikileaks was certainly related to matter of public policy, was he actually expressing an opinion on policy? Or was he simply threatening private firms for facilitating the dissemination of speech he didn't like? Legislators rightly enjoy broad leeway to speak their mind about legislative matters and criticize their political opponents, but should a legislator's own First Amendment rights enable him to trample the First Amendment rights of private citizens engaged in political discourse?

If the First Amendment doesn't protect Sen. Lieberman's attack on Wikileaks, he may still enjoy immunity from suit. Under the doctrine of qualified immunity, legislators cannot be held personally liable or forced to stand trial for committing unlawful actions in their official, non-legislative capacity unless they violate "clearly established law." (Legislators enjoy absolute immunity for actions they undertake in a legislative capacity).

As an attorney and former state Attorney General, Sen. Lieberman should have known full well that his actions were directly antithetical to Wikileaks' First Amendment rights. As such, he may not enjoy the protections of qualified immunity. Consider this excerpt from a ruling by the Eighth Circuit in Zilich v. Longo (34 F.3d 359):

We also agree with the findings of the district court that Zilich's First Amendment right of free speech was "clearly established" for qualified immunity purposes. The law is well settled in this Circuit that retaliation under color of law for the exercise of First Amendment rights is unconstitutional, and "retaliation claims" have been asserted in various factual scenarios.

Even if Lieberman did not violate any "clearly established law," Wikileaks might still be able to obtain an injunction to prevent Lieberman from making any further statements pressuring private companies to terminate service to Wikileaks. This wouldn't undo the harm the site has already suffered on account of Lieberman's "public request," of course, but at least it would mark an important symbolic victory for Wikileaks — and for the First Amendment.

A crucial question in determining whether Wikileaks has grounds for a First Amendment claim against Lieberman is whether the site's ongoing dissemination of the 250,000 leaked cables is protected by the First Amendment. On one hand, Julian Assange may be guilty of violating the Espionage Act of 1917, as Sen. Dianne Feinstein argues forcefully in an op-ed in today's The Wall Street Journal. On the other hand, the Wikileaks website may well enjoy the same First Amendment protection that the Pentagon Papers were found by the Supreme Court to enjoy in New York Times Co. v. United States. Via the WSJ Law Blog, which recently interviewed Jack Balkin of Yale Law School:

On the First Amendment question, Balkin said most First Amendment lawyers would say that preventing the publication of material "is justified only where absolutely necessary to prevent almost immediate and imminent disaster. It's an extremely high standard."

Balkin said that the standard for exacting criminal punishment or winning a civil injunction after publication, as might be the situation in the WikiLeaks case, is less settled. "But one assumes the standard is going to be very very high too."

An interesting 2005 opinion from the Eighth Circuit (Dossett v. First State Bank, 399 F.3d 940) suggests that Wikileaks might even have a case against Amazon as well, depending on the specific nature of the interactions between Amazon and Sen. Lieberman's office. Under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, private entities may face civil action if they conspire with government to deprive anybody within U.S. jurisdiction of their constitutional rights. Under Dossett, if Amazon "willfully participated with state officials and reached a mutual understanding concerning the unlawful objective of a conspiracy," Wikileaks may be able to collect damages for harm it incurred due to Amazon's termination of its service.

Whether Lieberman's actions are legal or not — and whatever you think about Wikileaks in general — his actions aimed at coercing private companies to terminate service to Wikileaks should deeply concern anybody who cares about free speech. As Glenn Greenwald put it:

That Joe Lieberman is abusing his position as Homeland Security Chairman to thuggishly dictate to private companies which websites they should and should not host — and, more important, what you can and cannot read on the Internet — is one of the most pernicious acts by a U.S. Senator in quite some time.

Unfortunately, this is just the latest instance of a politician "thuggishly" pressuring a private firm to stifle speech. A few months ago, I wrote about a group of state attorneys general successfully bullying Craigslist into terminating its legal "adult services" section. And back in 2008, I wrote about former New York Attorney General Andrew Cuomo strong-arming Usenet providers into shutting down dozens of newsgroups in their entirety simply because they contained a handful of illegal files.

A victory for Wikileaks against Joe Lieberman would set a powerful precedent discouraging thuggish politicians from campaigning against Internet sites protected by the First Amendment.

http://www.tableausoftware.com/blog/w...

Coming soon . . .

A Response to Nick Carr on Privacy & Trade-Offs

This is a response to Nick Carr's recent piece, "The Attack on Do Not Track," in which he goes after me for some comments I made in this essay about the trade-offs at work in the privacy and online advertising debates. In his critique of my essay, he argues:

What the FTC is suggesting is that the unwritten quid pro quo be written, and that the general agreement be made specific. Does Thierer really believe that invisible tradeoffs are somehow better than visible ones? Shouldn't people know the cost of "free" services, and then be allowed to make decisions based on their own cost-benefit analysis? Isn't that the essence of the free market that Thierer so eloquently celebrates?

My response to Nick follows.

Nick… Did I anywhere suggest that "invisible tradeoffs are somehow better than visible ones?" I can't remember saying that anywhere, so perhaps you can point to where I did. I don't think you'll find anything when you conduct your search since I know for a fact that I have never suggested such a thing.

That being said, strict contracting and consent models are not always possible in a free market economy, even if they are ideal. In essence, much of the history of advertising and marketing is built on the sort of "unwritten quid pro quos" you deride in your essay. Are you against radio or television advertising on similar grounds? Print ads? Direct mail? Billboards? There are steps you can take to avoid advertising and marketing in those contexts, but few of us would expect any sort of formal contact and consent form to be delivered to our attention beforehand. And opt-ing out of them entirely is very difficult. So, while I agree that, generally speaking, "people [should] know the cost of 'free' services, and then be allowed to make decisions based on their own cost-benefit analysis," let's understand that such ideal textbook models of perfect information and informed consent aren't always possible.

I will admit, however, that the difference with online advertising is that personal information may be collected about the consumer of the advertising in question. That did not always occur as part of those previous advertising "quid pro quos." Understandably, this raises the blood pressure of those who want to "property-tize" personal information and, in essence, apply a copyright-like permissions-based regime to any collection or reproduction of such information. Such an information control regime will be challenging to enforce, especially in light of the significant amounts of personal information that we voluntarily place online about ourselves. [See my earlier essay, "Privacy as an Information Control Regime: The Challenges Ahead" for further discussion.]

Nonetheless, an ideal world would be one in which trade-offs were more visible and consent / contracting was easier, whether we are talking about privacy, copyrighted material, or anything else. For example, in the context of online child safety and potentially objectionable media content, I have long argued that:

The ideal state of affairs, therefore, would be a nation of fully empowered parents who have the ability to perfectly tailor their family's media consumption habits to their specific values and preferences. Specifically, parents or guardians would have (1) the information necessary to make informed decisions and (2) the tools and methods necessary to act upon that information. Importantly, those tools and methods would give them the ability to not only block objectionable materials, but also to more easily find content they feel is appropriate for their families.

My former colleague Berin Szoka has applied this same 'ideal world' model to privacy in this filing to the Federal Trade Commission:

In an ideal world, adults would be fully empowered to tailor privacy decisions, like speech decisions, to their own values and preferences ("household standards"). Specifically, in an ideal world, adults (and parents) would have (1) the information necessary to make informed decisions and (2) the tools and methods necessary to act upon that information. Importantly, those tools and methods would give them the ability to block the things they don't like—annoying ads or the collection of data about them, as well as objectionable content.

Again, this would move us close to an explicit contracting / consent regime for the media content in question in both cases. Is it desirable? You bet. Is it possible? Likely not. Can we strive to get closer to the ideal state? Yes, but not without costs. And that's the key point I was trying to get across in my earlier essay on Do Not Track. The trade-offs here are real and could be quite profound for online content and culture. If we move toward a more rigorous information control regime to restrict personal information flows in the name of protecting privacy, we should not be surprised when that trade-off becomes more explicit–and expensive.

One final point. You argue that "the suggestion that people shouldn't be allowed to make informed choices about their privacy because some businesses may suffer as a result of those choices is ludicrous and even offensive." Again, I've already said that we can strive for more and better informed consent models, but you are pretending here it's far simpler than it is in reality. And I've already noted that the important point here is not protecting businesses, per se, but rather understanding that online content and culture is currently primarily subsidized by advertising business models that will be forcibly broken by regulation, and that we should consider the trade-offs that entails. Finally, is there any role for personal responsibility in your view? After all, there are steps that websurfers can take to address unwanted advertising and data collection techniques. Here's a short list of privacy solutions that my former PFF colleagues put together. If we expect consumers to exercise some personal responsibility to avoid unwanted content or communications in the free speech / online child safety context, why not here in the privacy context as well?

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower