Adam Thierer's Blog, page 123

July 1, 2011

Drunk on Wireless Taxes

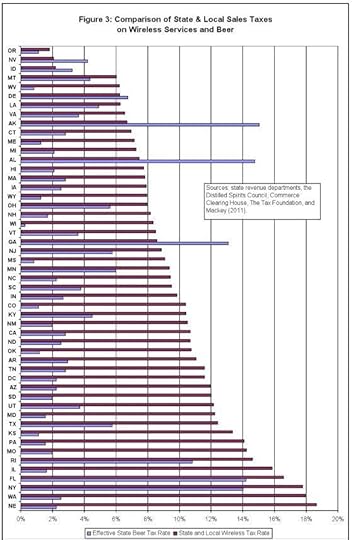

As we've noted here before, state and local politicians just love wireless taxes. They are going up, up, up. Dan Rothschild outlined this disturbing trend in his recent Mercatus Center paper making "The Case Against Taxing Cell Phone Subscribers," and I discussed it in my recent Forbes essay lambasting the "Talking Tax." Another new study by Glenn Woroch of the Georgetown University School of Business notes how "The 'Wireless Tax Premium' Harms American Consumers and Squanders the Potential of the Mobile Economy." Woroch estimates that "the American consumer forgoes over $15 billion in surplus annually compared to when cell phones receive the

As we've noted here before, state and local politicians just love wireless taxes. They are going up, up, up. Dan Rothschild outlined this disturbing trend in his recent Mercatus Center paper making "The Case Against Taxing Cell Phone Subscribers," and I discussed it in my recent Forbes essay lambasting the "Talking Tax." Another new study by Glenn Woroch of the Georgetown University School of Business notes how "The 'Wireless Tax Premium' Harms American Consumers and Squanders the Potential of the Mobile Economy." Woroch estimates that "the American consumer forgoes over $15 billion in surplus annually compared to when cell phones receive the

same tax treatment as other goods and service." Read the entire study but I want to draw everyone's attention to this chart that appears on page 7 of the report comparing state and local wireless taxes burdens to beer taxes. It really makes you realize just how drunk on wireless taxes are local lawmakers have become! [Click to enlarge. Red bar = wireless taxes.]

June 30, 2011

★ Twitter, the Monopolist? Is this Tim Wu's "Threat Regime" In Action?

According to a report today from SAI Business Insider, "The Federal Trade Commission is actively investigating Twitter and the way it deals with the companies building applications and services for its platform." Apparently the agency has reached out to some competing application / platform providers to ask questions about Twitter's recent efforts to exert more control over the uses of its API by third parties. [The Wall Street Journal confirms the FTC's interest in Twitter.]

It remains to be seen whether this leads to any serious regulatory action against Twitter by the FTC, but such a move wouldn't necessarily be surprising considering the more activist tilt of the agency recently. It's even less surprising considering that Columbia University law professor and prolific cyberlaw scholar Tim Wu was appointed as a senior advisor to the FTC earlier this year. When the announcement of Wu's appointment was made, the Wall Street Journal kicked off an article with the warning, "Silicon Valley has a new fear factor." It seems the Journal may have been on to something!

It's impossible to know how much of an influence Tim Wu is having on the agency, but as I have noted here before, Prof. Wu is man with a healthy appetite for regulatory activism. [See all my essays about Wu's work here.] Moreover, he's a man who has already determined that Twitter is a "monopolist" in his November 13, 2010 Wall Street Journal op-ed, "In the Grip of the New Monopolists."

That essay prompted a fiery response from me ["Tim Wu Redefines Monopoly"] as well as a far more reasoned essay by antitrust gurus Geoff Manne and Josh Wright ["What's An Internet Monopolist? A Reply to Professor Wu."] Prof. Wu was kind enough to swing by the TLF and respond to my criticisms in an essay "On the Definition of Monopoly," which he said served as a "corrective" to my earlier essay [even though I continue to believe that what I said fairly reflected the last four decades of economic wisdom on competition policy and that it is Wu who is well off the reservation with his expansionist views of antitrust enforcement].

Regardless of what one thinks about that exchange, if the FTC is moving forward with a case against Twitter, three practical questions need to be considered: (1) What's the relevant market? (2) Where's the harm? and (3) What's the remedy?

I'll briefly discuss each question below but should also mention that I already explored many of these issues in my essay, "A Vision of (Regulatory) Things to Come for Twitter," so I apologize in advance for the repetition. I will then discuss all this in the context of Tim Wu's latest law review article on "Agency Threats" and what he approvingly refers to as regulatory "threat regimes."

On Market Definition

As I noted in my previous essays, it's very much unclear how to define the contours of the market Twitter serves. After all, Twitter is only a few years old and it competes with many other forms of communication and information dissemination. For me, Twitter is a partial substitute for blogging, IMs, email, phone calls, RSS feeds, and even radio and television news. Yet, like most others, I continue to use all those other technologies and those technologies continue to pressure Twitter to innovate.

Whatever market it serves, however, Tim Wu is apparently willing to write off that market as already "in the grip" of Twitter. But does Wu really believe that nothing better will come along to compete against Twitter or even replace it entirely? It reminds me of all the hand-wringing we heard about AOL a decade ago when people predicted its "walled gardens" would someday rule the Internet and IM. And we all know how that turned out.

If you ask me, this episode again reflects the short-term, static snapshot thinking we all too often see at work in debates over media and technology policy. That is, many cyber-worrywarts are prone to taking snapshots of market activity and suggesting that temporary patterns are permanent disasters requiring immediate correction. Of course, a more dynamic view of progress and competition holds that "market failures" and "code failures" are ultimately better addressed by voluntary, spontaneous, bottom-up responses than by coercive, top-down approaches. [More on that conflict of visions in my book chapter on "The Case for Internet Optimism, Part 2 – Saving the Net From Its Supporters."]

Regardless, I just don't see how Wu or the FTC can claim Twitter has monopolized a market that is still so young that we can't even define it.

On Harm

Even if one accepted Wu's premise that Twitter was a monopolist, where is the harm? At least in theory, antitrust law is supposed to be about protecting consumer welfare, not competitors. If this whole thing is about UberMedia losing out in some bidding wars for alternative Twitter platforms, well, that's just pathetic. UberMedia is free to develop or bid on alternative Twitter applications or work with others to develop entirely new services. It's not like there's a shortage of them out there.

If the theory is that consumers are being harmed by Twitter exerting more control over its API, I would just remind everyone that (a) we don't pay a cent for the service that Twitter provides and (b) Twitter is still scrambling to find a way to monetize its service for the long-haul. There are also some legitimate security issues in play here that cut against the claim that what Twitter is doing is anti-consumer.

In sum, it is hard to understand where the harm lies in Twitter taking greater control of its API, and there's certainly nothing stopping rival innovators from tying to offer a competing service. 140-character text messages aren't exactly the stuff of traditional "information empires," as Wu would call them.

On Remedies

Finally, we come to the thorny issue of remedies. I suppose the easiest remedy would be a prohibition on Twitter acquiring any third-party applications provider that currently relies on Twitter's API. In other words, downstream vertical integration would be forbidden. But there's about 40 years of antitrust literature explaining why such integration is generally pro-innovation and pro-consumer and shouldn't be made illegal by antitrust law. Tim Wu may not buy that–and if you've read his recent book The Master Switch, you know he absolutely rejects it–but it is standard thinking in the field of industrial organization and antitrust economics today. Most of the economists at the FTC and DOJ could tell him as much.

Another alternative remedy might be Jonathan Zittrain's "API neutrality" idea, proposed in his 2008 book, The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It. Zittrain suggested that API neutrality–essentially a variant of Net neutrality but for application protocols–might be needed to ensure fair access to certain services or platforms to guarantee that digital "generativity" was not imperiled. On pg. 181 of the book, Zittrain argued that:

"If there is a present worldwide threat to neutrality in the movement of bits, it comes not from restrictions on traditional Internet access that can be evaded using generative PCs, but from enhancements to traditional and emerging appliancized services that are not open to third-party tinkering."

After engaging in some hand-wringing about "walled gardens" and "mediated experiences," Zittrain went on to ask: "So when should we consider network neutrality-style mandates for appliancized systems?" He responds to his own question as follows:

"The answer lies in that subset of appliancized systems that seeks to gain the benefits of third-party contributions while reserving the right to exclude it later. … Those who offer open APIs on the Net in an attempt to harness the generative cycle ought to remain application-neutral after their efforts have succeeded, so all those who built on top of their interface can continue to do so on equal terms." (p. 184)

This might be a fine generic principle, but Zittrain implies that this should be a legal standard to which online providers are held. At one point, he even alludes to the possibility of applying the common law principle of adverse possession more broadly in these contexts. He notes that adverse possession "dictates that people who openly occupy another's private property without the owner's explicit objection (or, for that matter, permission) can, after a lengthy period of time, come to legitimately acquire it." But he doesn't make it clear when it would be triggered as it pertains to digital platforms or APIs.

Nonetheless, one could imagine it would be one remedy antitrust officials might look to when considering what to do about Twitter exerting greater control over its API. Essentially, Twitter would become the equivalent of a public utility that all would have access to on regulated terms.

As I noted in the first of my many reviews of Zittrain's book, there are many problems with the logic of API neutrality or the application of adverse possession in these contexts. Here's my critique of the "API neutrality" notion (again, this is from 2008 so it now sounds a bit dated):

First, most developers who offer open APIs aren't likely to close them later precisely because they don't want to incur the wrath of "those who built on top of their interface." But, second, for the sake of argument, let's say they did want to abandoned previously open APIs and move to some sort of walled garden. So what? Isn't that called marketplace experimentation? Are we really going to make that illegal? Finally, if they were so foolish as to engage in such games, it might be the best thing that ever happened to the market and consumers since it could encourage more entry and innovation as people seek out more open, pro-generative alternatives. Consider this example: Now that Apple has opened to door to third-party iPhone development a bit with the SDK, does that mean that under Jonathan's proposed paradigm we should treat the iPhone as the equivalent of commoditized common carriage device? That seems incredibly misguided to me. If Steve Jobs opens the development door just a little bit only to slam it shut a short time later, he will pay dearly for that mistake in the marketplace. For God's sake, just spend a few minutes over on the Howard Forums or the PPC Geeks forum if you want to get a taste for the insane amount of tinkering going on out there in the mobile world right now on other systems. If Apple tries to roll back the clock, Microsoft and others will be all too happy to take their business by offering a wealth of devices that allow you to tinker to your heart's content. We should let such experiments continue and let the future of the Internet be determined by market choices, not regulatory choices such as forced API neutrality.

I think the same critique would apply to efforts to impose API neutrality on Twitter. Regardless, would such a remedy be imposed through targeted regulatory action, an antitrust consent decree, or perhaps through what Tim Wu calls "agency threats"?

Wu's "Threat Regime" Model of Internet Governance

Prof. Wu recently published a law review article on "Agency Threats" and what he approvingly refers to as "threat regimes." The paper is a "defense of regulatory threats in particular contexts." Here's a portion of the abstract:

The use of threats instead of law can be a useful choice — not simply a procedural end run. My argument is that the merits of any regulative modality cannot be determined without reference to the state of the industry being regulated. Threat regimes, I suggest, are important and are best justified when the industry is undergoing rapid change — under conditions of "high uncertainty." Highly informal regimes are most useful, that is, when the agency faces a problem in an environment in which facts are highly unclear and evolving. Examples include periods surrounding a newly invented technology or business model, or a practice about which little is known.

I'm extremely troubled by this reasoning and can think of a couple of alternative labels for such behavior by government agencies: unaccountable, above-the-law, unconstitutional, anti-democratic, thuggery, regulatory blackmail, and so on.

But what's even more troubling about Wu's thinking about "threat regimes" is that he assumes this arbitrary mode of governing-by-intimidation makes even more sense in fast-moving high-tech industries. That seems counter-intuitive. If a given sector finds itself in a state of "high uncertainty" as Wu calls it, doesn't that mean, by definition, it is dynamic and subject to forces that might bring about beneficial change? And shouldn't we assume that those are the last sectors we would want regulators monkeying with since bureaucrats lack the requisite knowledge of how to best guide the evolution of complex information technologies?

Wu seems to believe that regulators possess a crystal ball and a set of magical dials that can guide the evolution of technology markets to a better equilibrium through the use of constant Sunstein-ian "nudges" (or perhaps shoves). I think that's poppycock.

Regardless, once we realize that this is the way Tim Wu thinks, an FTC investigation into Twitter's current business practices starts to make a lot more sense. It's about creating a "threat regime" that intimidates Twitter into to playing by the arbitrary rules of Washington bureaucrats instead of responding to marketplace demands and developments in a natural, evolutionary way. In fact, in his "threats" essay, Wu explicitly rejects that model:

The second option—"wait and see"—may sound attractive because it allows the industry to develop in what might be called a natural way. This approach, however, makes a great sacrifice: the public's interest may be entirely unrepresented during the industry's formative period. The risk is that the industry's norms and business models will, effectively, be set without any public input. Waiting for the industry to settle down may result in undesirable practices that prove extremely hard to reverse or influence with rules issued later. To state the matter more colloquially, the industry may be "baked" by the time there is any real oversight or public input.

In essence, Wu desires a "mixed economy" model for high-tech sectors in which decision are guided at every juncture by the supposed wisdom of techno-cratic philosopher kings like himself. We must trust that he and his fellow regulators will guide us and our economy down an more enlightened path. And we must accept that some "threats" may be necessary to get the job done.

I find this mode of thinking disturbing in the extreme because of the rank hubris at the center of it. Regardless, Twitter appears to be well on its way to becoming a test case for Wu's "threat" model of Internet governance.

Twitter, the Monopolist? Is this Tim Wu's "Threat Regime" In Action?

According to a report today from SAI Business Insider, "The Federal Trade Commission is actively investigating Twitter and the way it deals with the companies building applications and services for its platform." Apparently the agency has reached out to some competing application / platform providers to ask questions about Twitter's recent efforts to exert more control over the uses of its API by third parties. [The Wall Street Journal confirms the FTC's interest in Twitter.]

It remains to be seen whether this leads to any serious regulatory action against Twitter by the FTC, but such a move wouldn't necessarily be surprising considering the more activist tilt of the agency recently. It's even less surprising considering that Columbia University law professor and prolific cyberlaw scholar Tim Wu was appointed as a senior advisor to the FTC earlier this year. When the announcement of Wu's appointment was made, the Wall Street Journal kicked off an article with the warning, "Silicon Valley has a new fear factor." It seems the Journal may have been on to something!

It's impossible to know how much of an influence Tim Wu is having on the agency, but as I have noted here before, Prof. Wu is man with a healthy appetite for regulatory activism. [See all my essays about Wu's work here.] Moreover, he's a man who has already determined that Twitter is a "monopolist" in his November 13, 2010 Wall Street Journal op-ed, "In the Grip of the New Monopolists."

That essay prompted a fiery response from me ["Tim Wu Redefines Monopoly"] as well as a far more reasoned essay by antitrust gurus Geoff Manne and Josh Wright ["What's An Internet Monopolist? A Reply to Professor Wu."] Prof. Wu was kind enough to swing by the TLF and respond to my criticisms in an essay "On the Definition of Monopoly," which he said served as a "corrective" to my earlier essay [even though I continue to believe that what I said fairly reflected the last four decades of economic wisdom on competition policy and that it is Wu who is well off the reservation with his expansionist views of antitrust enforcement].

Regardless of what one thinks about that exchange, if the FTC is moving forward with a case against Twitter, three practical questions need to be considered: (1) What's the relevant market? (2) Where's the harm? and (3) What's the remedy?

I'll briefly discuss each question below but should also mention that I already explored many of these issues in my essay, "A Vision of (Regulatory) Things to Come for Twitter," so I apologize in advance for the repetition. I will then discuss all this in the context of Tim Wu's latest law review article on "Agency Threats" and what he approvingly refers to as regulatory "threat regimes."

On Market Definition

As I noted in my previous essays, it's very much unclear how to define the contours of the market Twitter serves. After all, Twitter is only a few years old and it competes with many other forms of communication and information dissemination. For me, Twitter is a partial substitute for blogging, IMs, email, phone calls, RSS feeds, and even radio and television news. Yet, like most others, I continue to use all those other technologies and those technologies continue to pressure Twitter to innovate.

Whatever market it serves, however, Tim Wu is apparently willing to write off that market as already "in the grip" of Twitter. But does Wu really believe that nothing better will come along to compete against Twitter or even replace it entirely? It reminds me of all the hand-wringing we heard about AOL a decade ago when people predicted its "walled gardens" would someday rule the Internet and IM. And we all know how that turned out.

If you ask me, this episode again reflects the short-term, static snapshot thinking we all too often see at work in debates over media and technology policy. That is, many cyber-worrywarts are prone to taking snapshots of market activity and suggesting that temporary patterns are permanent disasters requiring immediate correction. Of course, a more dynamic view of progress and competition holds that "market failures" and "code failures" are ultimately better addressed by voluntary, spontaneous, bottom-up responses than by coercive, top-down approaches. [More on that conflict of visions in my book chapter on "The Case for Internet Optimism, Part 2 – Saving the Net From Its Supporters."]

Regardless, I just don't see how Wu or the FTC can claim Twitter has monopolized a market that is still so young that we can't even define it.

On Harm

Even if one accepted Wu's premise that Twitter was a monopolist, where is the harm? At least in theory, antitrust law is supposed to be about protecting consumer welfare, not competitors. If this whole thing is about UberMedia losing out in some bidding wars for alternative Twitter platforms, well, that's just pathetic. UberMedia is free to develop or bid on alternative Twitter applications or work with others to develop entirely new services. It's not like there's a shortage of them out there.

If the theory is that consumers are being harmed by Twitter exerting more control over its API, I would just remind everyone that (a) we don't pay a cent for the service that Twitter provides and (b) Twitter is still scrambling to find a way to monetize its service for the long-haul. There are also some legitimate security issues in play here that cut against the claim that what Twitter is doing is anti-consumer.

In sum, it is hard to understand where the harm lies in Twitter taking greater control of its API, and there's certainly nothing stopping rival innovators from tying to offer a competing service. 140-character text messages aren't exactly the stuff of traditional "information empires," as Wu would call them.

On Remedies

Finally, we come to the thorny issue of remedies. I suppose the easiest remedy would be a prohibition on Twitter acquiring any third-party applications provider that currently relies on Twitter's API. In other words, downstream vertical integration would be forbidden. But there's about 40 years of antitrust literature explaining why such integration is generally pro-innovation and pro-consumer and shouldn't be made illegal by antitrust law. Tim Wu may not buy that–and if you've read his recent book The Master Switch, you know he absolutely rejects it–but it is standard thinking in the field of industrial organization and antitrust economics today. Most of the economists at the FTC and DOJ could tell him as much.

Another alternative remedy might be Jonathan Zittrain's "API neutrality" idea, proposed in his 2008 book, The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It. Zittrain suggested that API neutrality–essentially a variant of Net neutrality but for application protocols–might be needed to ensure fair access to certain services or platforms to guarantee that digital "generativity" was not imperiled. On pg. 181 of the book, Zittrain argued that:

"If there is a present worldwide threat to neutrality in the movement of bits, it comes not from restrictions on traditional Internet access that can be evaded using generative PCs, but from enhancements to traditional and emerging appliancized services that are not open to third-party tinkering."

After engaging in some hand-wringing about "walled gardens" and "mediated experiences," Zittrain went on to ask: "So when should we consider network neutrality-style mandates for appliancized systems?" He responds to his own question as follows:

"The answer lies in that subset of appliancized systems that seeks to gain the benefits of third-party contributions while reserving the right to exclude it later. … Those who offer open APIs on the Net in an attempt to harness the generative cycle ought to remain application-neutral after their efforts have succeeded, so all those who built on top of their interface can continue to do so on equal terms." (p. 184)

This might be a fine generic principle, but Zittrain implies that this should be a legal standard to which online providers are held. At one point, he even alludes to the possibility of applying the common law principle of adverse possession more broadly in these contexts. He notes that adverse possession "dictates that people who openly occupy another's private property without the owner's explicit objection (or, for that matter, permission) can, after a lengthy period of time, come to legitimately acquire it." But he doesn't make it clear when it would be triggered as it pertains to digital platforms or APIs.

Nonetheless, one could imagine it would be one remedy antitrust officials might look to when considering what to do about Twitter exerting greater control over its API. Essentially, Twitter would become the equivalent of a public utility that all would have access to on regulated terms.

As I noted in the first of my many reviews of Zittrain's book, there are many problems with the logic of API neutrality or the application of adverse possession in these contexts. Here's my critique of the "API neutrality" notion (again, this is from 2008 so it now sounds a bit dated):

First, most developers who offer open APIs aren't likely to close them later precisely because they don't want to incur the wrath of "those who built on top of their interface." But, second, for the sake of argument, let's say they did want to abandoned previously open APIs and move to some sort of walled garden. So what? Isn't that called marketplace experimentation? Are we really going to make that illegal? Finally, if they were so foolish as to engage in such games, it might be the best thing that ever happened to the market and consumers since it could encourage more entry and innovation as people seek out more open, pro-generative alternatives. Consider this example: Now that Apple has opened to door to third-party iPhone development a bit with the SDK, does that mean that under Jonathan's proposed paradigm we should treat the iPhone as the equivalent of commoditized common carriage device? That seems incredibly misguided to me. If Steve Jobs opens the development door just a little bit only to slam it shut a short time later, he will pay dearly for that mistake in the marketplace. For God's sake, just spend a few minutes over on the Howard Forums or the PPC Geeks forum if you want to get a taste for the insane amount of tinkering going on out there in the mobile world right now on other systems. If Apple tries to roll back the clock, Microsoft and others will be all too happy to take their business by offering a wealth of devices that allow you to tinker to your heart's content. We should let such experiments continue and let the future of the Internet be determined by market choices, not regulatory choices such as forced API neutrality.

I think the same critique would apply to efforts to impose API neutrality on Twitter. Regardless, would such a remedy be imposed through targeted regulatory action, an antitrust consent decree, or perhaps through what Tim Wu calls "agency threats"?

Wu's "Threat Regime" Model of Internet Governance

Prof. Wu recently published a law review article on "Agency Threats" and what he approvingly refers to as "threat regimes." The paper is a "defense of regulatory threats in particular contexts." Here's a portion of the abstract:

The use of threats instead of law can be a useful choice — not simply a procedural end run. My argument is that the merits of any regulative modality cannot be determined without reference to the state of the industry being regulated. Threat regimes, I suggest, are important and are best justified when the industry is undergoing rapid change — under conditions of "high uncertainty." Highly informal regimes are most useful, that is, when the agency faces a problem in an environment in which facts are highly unclear and evolving. Examples include periods surrounding a newly invented technology or business model, or a practice about which little is known.

I'm extremely troubled by this reasoning and can think of a couple of alternative labels for such behavior by government agencies: unaccountable, above-the-law, unconstitutional, anti-democratic, thuggery, regulatory blackmail, and so on.

But what's even more troubling about Wu's thinking about "threat regimes" is that he assumes this arbitrary mode of governing-by-intimidation makes even more sense in fast-moving high-tech industries. That seems counter-intuitive. If a given sector finds itself in a state of "high uncertainty" as Wu calls it, doesn't that mean, by definition, it is dynamic and subject to forces that might bring about beneficial change? And shouldn't we assume that those are the last sectors we would want regulators monkeying with since bureaucrats lack the requisite knowledge of how to best guide the evolution of complex information technologies?

Wu seems to believe that regulators possess a crystal ball and a set of magical dials that can guide the evolution of technology markets to a better equilibrium through the use of constant Sunstein-ian "nudges" (or perhaps shoves). I think that's poppycock.

Regardless, once we realize that this is the way Tim Wu thinks, an FTC investigation into Twitter's current business practices starts to make a lot more sense. It's about creating a "threat regime" that intimidates Twitter into to playing by the arbitrary rules of Washington bureaucrats instead of responding to marketplace demands and developments in a natural, evolutionary way. In fact, in his "threats" essay, Wu explicitly rejects that model:

The second option—"wait and see"—may sound attractive because it allows the industry to develop in what might be called a natural way. This approach, however, makes a great sacrifice: the public's interest may be entirely unrepresented during the industry's formative period. The risk is that the industry's norms and business models will, effectively, be set without any public input. Waiting for the industry to settle down may result in undesirable practices that prove extremely hard to reverse or influence with rules issued later. To state the matter more colloquially, the industry may be "baked" by the time there is any real oversight or public input.

In essence, Wu desires a "mixed economy" model for high-tech sectors in which decision are guided at every juncture by the supposed wisdom of techno-cratic philosopher kings like himself. We must trust that he and his fellow regulators will guide us and our economy down an more enlightened path. And we must accept that some "threats" may be necessary to get the job done.

I find this mode of thinking disturbing in the extreme because of the rank hubris at the center of it. Regardless, Twitter appears to be well on its way to becoming a test case for Wu's "threat" model of Internet governance.

June 29, 2011

★ Terrific Speech by FCC's Rob McDowell on "Technology & the Sovereignty of the Individual"

FCC Commissioner Robert M. McDowell delivered a terrific speech this week on "Technology and the Sovereignty of the Individual" at a broadband conference in Stockholm, Sweden. The speech serves as another reminder that McDowell is one of those ultimate rare birds: a regulator who is a first-rate intellectual thinker and a great champion of individual liberty. It's a beautiful statement in defense of real Internet freedom. I can't recall ever seeing another federal official cite the great Bruno Leoni in a speech!

FCC Commissioner Robert M. McDowell delivered a terrific speech this week on "Technology and the Sovereignty of the Individual" at a broadband conference in Stockholm, Sweden. The speech serves as another reminder that McDowell is one of those ultimate rare birds: a regulator who is a first-rate intellectual thinker and a great champion of individual liberty. It's a beautiful statement in defense of real Internet freedom. I can't recall ever seeing another federal official cite the great Bruno Leoni in a speech!

Here's a sample of what Commissioner McDowell had to say:

To propel freedom's momentum, policy makers should remember that, since their inception, the Internet and mobile connectivity have migrated further away from government control. As the result of longstanding international consensus, the Internet itself has become the greatest deregulatory success story of all time. To continue to promote freedom and prosperity, regulators should continue to rely on the "bottom up" nongovernmental Internet governance bodies that have a perfect record of keeping the 'Net working and open. We must heed the advice of leaders like Neelie Kroes, who has consistently called on regulators to "avoid over-hasty regulatory intervention," and steer clear of "unnecessary measures which may hinder new efficient business models from emerging." I couldn't agree more. Changing course now could not only trigger an avalanche of international regulation, but it could halt the progress of freedom's march as well.

With these pragmatic principles in mind, freedom-loving governments everywhere should resist the temptation to regulate in the absence of pervasive market failure. Needless government intrusion into the Internet's affairs provides nefarious authoritarian regimes with the political cover they desire to justify their interference with the 'Net. To prevent an escalation of international regulation, we should encourage the kind of positive and constructive chaos that only unfettered competition can produce. We should adopt spectrum policies that promote flexible uses, spectrum allocation through fair auction processes and, when appropriate, unlicensed use of the airwaves to spur innovation and adoption. Fueling freedom in this way will turn the world upside down for the better.

Preach it, brother! Read the whole thing.

Terrific Speech by FCC's Rob McDowell on "Technology & the Sovereignty of the Individual"

FCC Commissioner Robert M. McDowell delivered a terrific speech this week on "Technology and the Sovereignty of the Individual" at a broadband conference in Stockholm, Sweden. The speech serves as another reminder that McDowell is one of those ultimate rare birds: a regulator who is a first-rate intellectual thinker and a great champion of individual liberty. It's a beautiful statement in defense of real Internet freedom. I can't recall ever seeing another federal official cite the great Bruno Leoni in a speech!

FCC Commissioner Robert M. McDowell delivered a terrific speech this week on "Technology and the Sovereignty of the Individual" at a broadband conference in Stockholm, Sweden. The speech serves as another reminder that McDowell is one of those ultimate rare birds: a regulator who is a first-rate intellectual thinker and a great champion of individual liberty. It's a beautiful statement in defense of real Internet freedom. I can't recall ever seeing another federal official cite the great Bruno Leoni in a speech!

Here's a sample of what Commissioner McDowell had to say:

To propel freedom's momentum, policy makers should remember that, since their inception, the Internet and mobile connectivity have migrated further away from government control. As the result of longstanding international consensus, the Internet itself has become the greatest deregulatory success story of all time. To continue to promote freedom and prosperity, regulators should continue to rely on the "bottom up" nongovernmental Internet governance bodies that have a perfect record of keeping the 'Net working and open. We must heed the advice of leaders like Neelie Kroes, who has consistently called on regulators to "avoid over-hasty regulatory intervention," and steer clear of "unnecessary measures which may hinder new efficient business models from emerging." I couldn't agree more. Changing course now could not only trigger an avalanche of international regulation, but it could halt the progress of freedom's march as well.

With these pragmatic principles in mind, freedom-loving governments everywhere should resist the temptation to regulate in the absence of pervasive market failure. Needless government intrusion into the Internet's affairs provides nefarious authoritarian regimes with the political cover they desire to justify their interference with the 'Net. To prevent an escalation of international regulation, we should encourage the kind of positive and constructive chaos that only unfettered competition can produce. We should adopt spectrum policies that promote flexible uses, spectrum allocation through fair auction processes and, when appropriate, unlicensed use of the airwaves to spur innovation and adoption. Fueling freedom in this way will turn the world upside down for the better.

Preach it, brother! Read the whole thing.

June 28, 2011

★ A Response to Leland Yee & James Steyer on What Motivated Video Game Decision

Yesterday's 7-2 decision in Brown v. EMA [summaries here from me + Berin Szoka] was one of those historic First Amendment rulings that tends to bring out passions in people. You either loved it or hated it. But it's sad to see some critics on the losing end of the case declaring that only greed could have possibly motivated the Court's decision.

For example, California Senator Leland Yee, the author of the law that the Supreme Court struck down yesterday, obviously wasn't happy about the outcome of the case. Neither was James Steyer, CEO of the advocacy group Common Sense Media, who has been a vociferous advocate of the California law and measures like it. What they had to say in response to the decision, however, was outlandish and juvenile. In essence, they both claimed that the Supreme Court only struck down the law to make video game developers and retailers happy.

"Unfortunately, the majority of the Supreme Court once again put the interests of corporate America before the interests of our children," Leland Yee said in a post on his website yesterday. "As a result of their decision, Wal-Mart and the video game industry will continue to make billions of dollars at the expense of our kids' mental health and the safety of our community. It is simply wrong that the video game industry can be allowed to put their profit margins over the rights of parents and the well-being of children." Jim Steyer reached a similar conclusion: "Today's decision is a disappointing one for parents, educators, and all who care about kids," he said. "Today, the multi-billion dollar video game industry is celebrating the fact that their profits have been protected, but we will continue to fight for the best interests of kids and families."

Mr. Yee and Mr. Steyer seem to be under the impression that the Court and supporters of its ruling in Brown cannot possibly care about children and that something sinister motivates our passion about the victory. Apparently we're all just apparently in it to make video game industry fat cats and retailing giants happy! That's a truly insulting position for Mr. Yee and Mr. Steyer to adopt. Perhaps it is just because they are sore about the outcome in the case that are adopting such rhetorical tactics. Regardless, I think they do themselves, their constituencies, and the public a great injustice by suggesting that only greed could possibly be motivating the outcome in this case.

Why is it so hard for Mr. Yee and Mr. Steyer to believe that many of us — like the majority writing for the Court in Brown — believe that video games represent valuable, constitutionally protected speech and that laws like those in California are an affront to First Amendment rights we cherish? What Mr. Yee and Mr. Steyer are asking us to believe is that all those average gamers and free speech advocates who lined up behind the video game industry and merchants who brought this case did so only out of a concern about the welfare of those companies. Preposterous! Anyone who knows anything about game industry politics knows that some rather serious tensions exist between gamers, game developers, and game retailers.

Incidentally, it's particular silly for Mr. Yee to single out Wal-Mart in his comment yesterday since Wal-Mart actually goes to great lengths to keep "Mature"-rated games out of the hands of minors who might try to purchase them on their own. But I could care less about how much money Wal-Mart, any other retailer, or any video game developer makes from selling games. That's the last thing on the mind of most First Amendment supporters when they praise this decision and it's ridiculous that Mr. Yee and Mr. Steyer would list it as the primary motivation of the Court or supporters of the decision.

And then there's Mr. Steyer's comment that "today's decision is a disappointing one for parents, educators, and all who care about kids." Utterly insulting tripe. Millions of parents like me "care about kids" passionately and devote most of our lives to raising them properly. I understand you want to help us do that, but you are not helping when you insult the very people you say your organization exists to support.

I have repeatedly praised Common Sense Media here and elsewhere for many of the outstanding services and information they provide to parents. My wife and I regularly consult CSM's excellent movie and video game summaries before we let our kids consume certain titles. It was also my great privilege to serve on a blue ribbon online child safety task force that CSM created and co-sponsored.

But when Mr. Steyer veers into this sort of hysterical 'you're-either-for-these-laws-or-you're-against-children' sort of lunacy, it really makes me question whether I should frequent his organization's website anymore or have any further interaction with this group. While I appreciate CSM's efforts to empower parents with more and better information about the content our families consume, it is insulting in the extreme for Mr. Steyer to suggest that you can't "care about kids" and also care about the First Amendment.

Like the majority of the justices on the Court, I support limits on how our government controls speech because we live in a nation that cherishes freedom of expression and personal responsibility. We should not expect Uncle Sam to act as a national nanny and make subjective determinations about what is best for our families. As Catherine Ross, a professor at George Washington University Law School, noted in a nice Washington Post oped, "By rejecting this radical path, the justices [in Brown] protected our children by preserving our liberty."

Quite right. I'm proud the Supreme Court sided with freedom yesterday and against the sort of nannyism from above that Mr. Steyer and Mr. Yee apparently favor and equate with "caring about kids." These men obviously don't take First Amendment rights quite as seriously as some of the rest of us. But shame on them for claiming that just because many of us (or the Courts) do take these rights and responsibilities seriously that it somehow means we don't care about our children or that we only believe these things in order to make corporations happy.

A Response to Leland Yee & James Steyer on What Motivated Video Game Decision

Yesterday's 7-2 decision in Brown v. EMA [summaries here from me + Berin Szoka] was one of those historic First Amendment rulings that tends to bring out passions in people. You either loved it or hated it. But it's sad to see some critics on the losing end of the case declaring that only greed could have possibly motivated the Court's decision.

For example, California Senator Leland Yee, the author of the law that the Supreme Court struck down yesterday, obviously wasn't happy about the outcome of the case. Neither was James Steyer, CEO of the advocacy group Common Sense Media, who has been a vociferous advocate of the California law and measures like it. What they had to say in response to the decision, however, was outlandish and juvenile. In essence, they both claimed that the Supreme Court only struck down the law to make video game developers and retailers happy.

"Unfortunately, the majority of the Supreme Court once again put the interests of corporate America before the interests of our children," Leland Yee said in a post on his website yesterday. "As a result of their decision, Wal-Mart and the video game industry will continue to make billions of dollars at the expense of our kids' mental health and the safety of our community. It is simply wrong that the video game industry can be allowed to put their profit margins over the rights of parents and the well-being of children." Jim Steyer reached a similar conclusion: "Today's decision is a disappointing one for parents, educators, and all who care about kids," he said. "Today, the multi-billion dollar video game industry is celebrating the fact that their profits have been protected, but we will continue to fight for the best interests of kids and families."

Mr. Yee and Mr. Steyer seem to be under the impression that the Court and supporters of its ruling in Brown cannot possibly care about children and that something sinister motivates our passion about the victory. Apparently we're all just apparently in it to make video game industry fat cats and retailing giants happy! That's a truly insulting position for Mr. Yee and Mr. Steyer to adopt. Perhaps it is just because they are sore about the outcome in the case that are adopting such rhetorical tactics. Regardless, I think they do themselves, their constituencies, and the public a great injustice by suggesting that only greed could possibly be motivating the outcome in this case.

Why is it so hard for Mr. Yee and Mr. Steyer to believe that many of us — like the majority writing for the Court in Brown — believe that video games represent valuable, constitutionally protected speech and that laws like those in California are an affront to First Amendment rights we cherish? What Mr. Yee and Mr. Steyer are asking us to believe is that all those average gamers and free speech advocates who lined up behind the video game industry and merchants who brought this case did so only out of a concern about the welfare of those companies. Preposterous! Anyone who knows anything about game industry politics knows that some rather serious tensions exist between gamers, game developers, and game retailers.

Incidentally, it's particular silly for Mr. Yee to single out Wal-Mart in his comment yesterday since Wal-Mart actually goes to great lengths to keep "Mature"-rated games out of the hands of minors who might try to purchase them on their own. But I could care less about how much money Wal-Mart, any other retailer, or any video game developer makes from selling games. That's the last thing on the mind of most First Amendment supporters when they praise this decision and it's ridiculous that Mr. Yee and Mr. Steyer would list it as the primary motivation of the Court or supporters of the decision.

And then there's Mr. Steyer's comment that "today's decision is a disappointing one for parents, educators, and all who care about kids." Utterly insulting tripe. Millions of parents like me "care about kids" passionately and devote most of our lives to raising them properly. I understand you want to help us do that, but you are not helping when you insult the very people you say your organization exists to support.

I have repeatedly praised Common Sense Media here and elsewhere for many of the outstanding services and information they provide to parents. My wife and I regularly consult CSM's excellent movie and video game summaries before we let our kids consume certain titles. It was also my great privilege to serve on a blue ribbon online child safety task force that CSM created and co-sponsored.

But when Mr. Steyer veers into this sort of hysterical 'you're-either-for-these-laws-or-you're-against-children' sort of lunacy, it really makes me question whether I should frequent his organization's website anymore or have any further interaction with this group. While I appreciate CSM's efforts to empower parents with more and better information about the content our families consume, it is insulting in the extreme for Mr. Steyer to suggest that you can't "care about kids" and also care about the First Amendment.

Like the majority of the justices on the Court, I support limits on how our government controls speech because we live in a nation that cherishes freedom of expression and personal responsibility. We should not expect Uncle Sam to act as a national nanny and make subjective determinations about what is best for our families. As Catherine Ross, a professor at George Washington University Law School, noted in a nice Washington Post oped, "By rejecting this radical path, the justices [in Brown] protected our children by preserving our liberty."

Quite right. I'm proud the Supreme Court sided with freedom yesterday and against the sort of nannyism from above that Mr. Steyer and Mr. Yee apparently favor and equate with "caring about kids." These men obviously don't take First Amendment rights quite as seriously as some of the rest of us. But shame on them for claiming that just because many of us (or the Courts) do take these rights and responsibilities seriously that it somehow means we don't care about our children or that we only believe these things in order to make corporations happy.

★ Sacrificing Consumer Welfare in the Search Bias Debate, Part II

[Cross-Posted at Truthonthemarket.com]

I did not intend for this to become a series (Part I), but I underestimated the supply of analysis simultaneously invoking "search bias" as an antitrust concept while waving it about untethered from antitrust's institutional commitment to protecting consumer welfare. Harvard Business School Professor Ben Edelman offers the latest iteration in this genre. We've criticized his claims regarding search bias and antitrust on precisely these grounds.

For those who have not been following the Google antitrust saga, Google's critics allege Google's algorithmic search results "favor" its own services and products over those of rivals in some indefinite, often unspecified, improper manner. In particular, Professor Edelman and others — including Google's business rivals — have argued that Google's "bias" discriminates most harshly against vertical search engine rivals, i.e. rivals offering search specialized search services. In framing the theory that "search bias" can be a form of anticompetitive exclusion, Edelman writes:

Search bias is a mechanism whereby Google can leverage its dominance in search, in order to achieve dominance in other sectors. So for example, if Google wants to be dominant in restaurant reviews, Google can adjust search results, so whenever you search for restaurants, you get a Google reviews page, instead of a Chowhound or Yelp page. That's good for Google, but it might not be in users' best interests, particularly if the other services have better information, since they've specialized in exactly this area and have been doing it for years.

I've wondered what model of antitrust-relevant conduct Professor Edelman, an economist, has in mind. It is certainly well known in both the theoretical and empirical antitrust economics literature that "bias" is neither necessary nor sufficient for a theory of consumer harm; further, it is fairly obvious as a matter of economics that vertical integration can be, and typically is, both efficient and pro-consumer. Still further, the bulk of economic theory and evidence on these contracts suggest that they are generally efficient and a normal part of the competitive process generating consumer benefits. Vertically integrated firms may "bias" their own content in ways that increase output; the relevant point is that self-promoting incentives in a vertical relationship can be either efficient or anticompetitive depending on the circumstances of the situation. The empirical literature suggests that such relationships are mostly pro-competitive and that restrictions upon firms' ability to enter them generally reduce consumer welfare. Edelman is an economist, with a Ph.D. from Harvard no less, and so I find it a bit odd that he has framed the "bias" debate outside of this framework, without regard to consumer welfare, and without reference to any of this literature or perhaps even an awareness of it. Edelman's approach appears to be a declaration that a search engine's placement of its own content, algorithmically or otherwise, constitutes an antitrust harm because it may harm rivals — regardless of the consequences for consumers. Antitrust observers might parallel this view to the antiquated "harm to competitors is harm to competition" approach of antitrust dating back to the 1960s and prior. These parallels would be accurate. Edelman's view is flatly inconsistent with conventional theories of anticompetitive exclusion presently enforced in modern competition agencies or antitrust courts.

But does Edelman present anything more than just a pre-New Learning-era bias against vertical integration? I'm beginning to have my doubts. In an interview in Politico (login required), Professor Edelman offers two quotes that illuminate the search-bias antitrust theory — unfavorably. Professor Edelman begins with what he describes as a "simple" solution to the search bias problem:

I don't think it's out of the question given the complexity of what Google has built and its persistence in entering adjacent, ancillary markets. A much simpler approach, if you like things that are simple, would be to disallow Google from entering these adjacent markets. OK, you want to be dominant in search? Stay out of the vertical business, stay out of content.

The problems here should be obvious. Yes, a per se prohibition on vertical integration by Google into other economic activities would be quite simple; simple and thoroughly destructive. The mildly more interesting inquiry is what Edelman proposes Google ought provide. May, under Edelman's view of a proper regulatory regime, Google answer address search queries by providing a map? May Google answer product queries with shopping results? Is the answer to those questions "yes" if and only if Google serves up some one else's shopping results or map? What if consumers prefer Google's shopping result or map because it is more responsive to the query. Note once again that Edelman's answers do not turn on consumer welfare. His answers are a function of the anticipated impact of Google's choices to engage in those activities upon rival vertical search engines. Consumer welfare is not the center of Edelman's analysis; indeed, it is unclear what role consumer welfare plays in Edelman's analysis at all. Edelman simply applies his prior presumption that Google's conduct, even if it produces real gains for consumers, is or should be actionable as an antitrust claim upon a demonstration that Google's own services are ranked highly on its own search engine — even if Google-affiliated content is ranked highly by other search engines! (See Danny Sullivan making that point nicely in this post). Edelman's proscription ignores the efficiencies of vertical integration and the benefits to consumers entirely. It may be possible to articulate a coherent anticompetitive theory involving so-called search bias that could then be tested against the real world evidence. Edelman has not.

Professor Edelman's other quotation from the profile of the "academic wunderkind" that drew my attention was the following answer in response to the question "which search engine do you use?" After explaining that he probably uses Google and Bing in proportion to their market shares, Professor Edelman is quoted as saying:

If your house is on fire and you forgot the number for the fire department, I'd encourage you to use Google. When it counts, if Google is one percent better for one percent of searches and both options are free, you'd be crazy not to use it. But if everyone makes that decision, we head towards a monopoly and all the problems experience reveals when a company controls too much.

By my lights, there is no clearer example of the sacrifice of consumer welfare in Edelman's approach to analyzing whether and how search engines and their results should be regulated. Note the core of Professor Edelman's position: if Google offers a superior product favored by all consumers, and if Google gains substantial market share because of this success as determined by consumers, we are collectively headed for serious problems redressable by regulation. In these circumstances, given the (1) lack of consumer lock-in for search engine use, (2) the overwhelming evidence that vertical integration is generally pro-competitive, and (3) the fact that consumers are generally enjoying the use of free services — one might think that any consumer-minded regulatory approach would carefully attempt to identify and distinguish potentially anticompetitive conduct so as to minimize the burden to consumers from inevitable false positives. With credit to antitrust and its hard-earned economic discipline, this is the approach suggested by modern antitrust doctrine. U.S. antitrust law requires a demonstration that consumers will be harmed by a challenged practice — not merely rivals. It is odd and troubling when an economist abandons the consumer welfare approach; it is yet more peculiar that an economist not only abandons the consumer welfare lodestar but also argues for (or at least presents an unequivocal willingness to accept) an ex ante prohibition on vertical integration altogether in this space.

I've no doubt that there are more sophisticated theories of which creative antitrust economists can conceive that come closer to satisfying the requirements of modern antitrust economics by focusing upon consumer welfare. Certainly, the economists who identify those theories will have their shot at convincing the FTC. Indeed, Section 5 might even open the door to theories ever-so slightly more creative and more open-ended that those that would be taken seriously in a Sherman Act inquiry. However, antitrust economists can and should remain intensely focused upon the impact of the conduct at issue — in this case, prominent algorithmic placement of Google's own affiliated content its rankings — on consumer welfare. Because Professor Edelman's views harken to the infamous days of antitrust that cast a pall over any business practice unpleasant for rivals — even if the practice delivered what consumers wanted. Edelman's theory is an offer to jeopardize consumers and protect rivals, and to brush the dust off antiquated antitrust theories and standards and apply them to today's innovative online markets. Modern antitrust has come a long way in its thinking over the past 50 years — too far to accept these competitor-centric theories of harm.

Sacrificing Consumer Welfare in the Search Bias Debate, Part II

[Cross-Posted at Truthonthemarket.com]

I did not intend for this to become a series (Part I), but I underestimated the supply of analysis simultaneously invoking "search bias" as an antitrust concept while waving it about untethered from antitrust's institutional commitment to protecting consumer welfare. Harvard Business School Professor Ben Edelman offers the latest iteration in this genre. We've criticized his claims regarding search bias and antitrust on precisely these grounds.

For those who have not been following the Google antitrust saga, Google's critics allege Google's algorithmic search results "favor" its own services and products over those of rivals in some indefinite, often unspecified, improper manner. In particular, Professor Edelman and others — including Google's business rivals — have argued that Google's "bias" discriminates most harshly against vertical search engine rivals, i.e. rivals offering search specialized search services. In framing the theory that "search bias" can be a form of anticompetitive exclusion, Edelman writes:

Search bias is a mechanism whereby Google can leverage its dominance in search, in order to achieve dominance in other sectors. So for example, if Google wants to be dominant in restaurant reviews, Google can adjust search results, so whenever you search for restaurants, you get a Google reviews page, instead of a Chowhound or Yelp page. That's good for Google, but it might not be in users' best interests, particularly if the other services have better information, since they've specialized in exactly this area and have been doing it for years.

I've wondered what model of antitrust-relevant conduct Professor Edelman, an economist, has in mind. It is certainly well known in both the theoretical and empirical antitrust economics literature that "bias" is neither necessary nor sufficient for a theory of consumer harm; further, it is fairly obvious as a matter of economics that vertical integration can be, and typically is, both efficient and pro-consumer. Still further, the bulk of economic theory and evidence on these contracts suggest that they are generally efficient and a normal part of the competitive process generating consumer benefits. Vertically integrated firms may "bias" their own content in ways that increase output; the relevant point is that self-promoting incentives in a vertical relationship can be either efficient or anticompetitive depending on the circumstances of the situation. The empirical literature suggests that such relationships are mostly pro-competitive and that restrictions upon firms' ability to enter them generally reduce consumer welfare. Edelman is an economist, with a Ph.D. from Harvard no less, and so I find it a bit odd that he has framed the "bias" debate outside of this framework, without regard to consumer welfare, and without reference to any of this literature or perhaps even an awareness of it. Edelman's approach appears to be a declaration that a search engine's placement of its own content, algorithmically or otherwise, constitutes an antitrust harm because it may harm rivals — regardless of the consequences for consumers. Antitrust observers might parallel this view to the antiquated "harm to competitors is harm to competition" approach of antitrust dating back to the 1960s and prior. These parallels would be accurate. Edelman's view is flatly inconsistent with conventional theories of anticompetitive exclusion presently enforced in modern competition agencies or antitrust courts.

But does Edelman present anything more than just a pre-New Learning-era bias against vertical integration? I'm beginning to have my doubts. In an interview in Politico (login required), Professor Edelman offers two quotes that illuminate the search-bias antitrust theory — unfavorably. Professor Edelman begins with what he describes as a "simple" solution to the search bias problem:

I don't think it's out of the question given the complexity of what Google has built and its persistence in entering adjacent, ancillary markets. A much simpler approach, if you like things that are simple, would be to disallow Google from entering these adjacent markets. OK, you want to be dominant in search? Stay out of the vertical business, stay out of content.

The problems here should be obvious. Yes, a per se prohibition on vertical integration by Google into other economic activities would be quite simple; simple and thoroughly destructive. The mildly more interesting inquiry is what Edelman proposes Google ought provide. May, under Edelman's view of a proper regulatory regime, Google answer address search queries by providing a map? May Google answer product queries with shopping results? Is the answer to those questions "yes" if and only if Google serves up some one else's shopping results or map? What if consumers prefer Google's shopping result or map because it is more responsive to the query. Note once again that Edelman's answers do not turn on consumer welfare. His answers are a function of the anticipated impact of Google's choices to engage in those activities upon rival vertical search engines. Consumer welfare is not the center of Edelman's analysis; indeed, it is unclear what role consumer welfare plays in Edelman's analysis at all. Edelman simply applies his prior presumption that Google's conduct, even if it produces real gains for consumers, is or should be actionable as an antitrust claim upon a demonstration that Google's own services are ranked highly on its own search engine — even if Google-affiliated content is ranked highly by other search engines! (See Danny Sullivan making that point nicely in this post). Edelman's proscription ignores the efficiencies of vertical integration and the benefits to consumers entirely. It may be possible to articulate a coherent anticompetitive theory involving so-called search bias that could then be tested against the real world evidence. Edelman has not.

Professor Edelman's other quotation from the profile of the "academic wunderkind" that drew my attention was the following answer in response to the question "which search engine do you use?" After explaining that he probably uses Google and Bing in proportion to their market shares, Professor Edelman is quoted as saying:

If your house is on fire and you forgot the number for the fire department, I'd encourage you to use Google. When it counts, if Google is one percent better for one percent of searches and both options are free, you'd be crazy not to use it. But if everyone makes that decision, we head towards a monopoly and all the problems experience reveals when a company controls too much.

By my lights, there is no clearer example of the sacrifice of consumer welfare in Edelman's approach to analyzing whether and how search engines and their results should be regulated. Note the core of Professor Edelman's position: if Google offers a superior product favored by all consumers, and if Google gains substantial market share because of this success as determined by consumers, we are collectively headed for serious problems redressable by regulation. In these circumstances, given the (1) lack of consumer lock-in for search engine use, (2) the overwhelming evidence that vertical integration is generally pro-competitive, and (3) the fact that consumers are generally enjoying the use of free services — one might think that any consumer-minded regulatory approach would carefully attempt to identify and distinguish potentially anticompetitive conduct so as to minimize the burden to consumers from inevitable false positives. With credit to antitrust and its hard-earned economic discipline, this is the approach suggested by modern antitrust doctrine. U.S. antitrust law requires a demonstration that consumers will be harmed by a challenged practice — not merely rivals. It is odd and troubling when an economist abandons the consumer welfare approach; it is yet more peculiar that an economist not only abandons the consumer welfare lodestar but also argues for (or at least presents an unequivocal willingness to accept) an ex ante prohibition on vertical integration altogether in this space.

I've no doubt that there are more sophisticated theories of which creative antitrust economists can conceive that come closer to satisfying the requirements of modern antitrust economics by focusing upon consumer welfare. Certainly, the economists who identify those theories will have their shot at convincing the FTC. Indeed, Section 5 might even open the door to theories ever-so slightly more creative and more open-ended that those that would be taken seriously in a Sherman Act inquiry. However, antitrust economists can and should remain intensely focused upon the impact of the conduct at issue — in this case, prominent algorithmic placement of Google's own affiliated content its rankings — on consumer welfare. Because Professor Edelman's views harken to the infamous days of antitrust that cast a pall over any business practice unpleasant for rivals — even if the practice delivered what consumers wanted. Edelman's theory is an offer to jeopardize consumers and protect rivals, and to brush the dust off antiquated antitrust theories and standards and apply them to today's innovative online markets. Modern antitrust has come a long way in its thinking over the past 50 years — too far to accept these competitor-centric theories of harm.

★ Pamela Samuelson on codifying the Google Books settlement

On the podcast this week, Pamela Samuelson, the Richard M. Sherman Distinguished Professor of Law at Berkeley Law School, discusses her new article in the Columbia Journal of Law & the Arts entitled, Legislative Alternatives to the Google Book Settlement. Samuelson discusses the settlement, which was ultimately rejected, and highlights what she deems to be positive aspects. One aspect includes making out-of-print works available to a broad audience while keeping transaction costs low. Samuelson suggests encompassing these aspects into legislative reform. The goal of such reform would strike a balance that benefits rights holders, as well as the general public, while generating competition through implementation of a licensing scheme.

Related Links

Legislative Alternatives to the Google Book Settlement , by Samuelson

"Judge Rejects Google Books Settlement," Wall Street Journal

"Explaining the Google Books Case Saga," Time Techland

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we'd like to ask you to comment at the web page for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower