Adam Thierer's Blog, page 120

August 1, 2011

Latest Industry USF Proposal

A couple days before Congress announced a debt deal, half a dozen telecommunications companies filed a plan on July 29 with the Federal Communications Commission that attempts to resolve a much longer-running set of negotiations over big bucks. The "America's Broadband Connectivity" Plan seeks to replace Universal Service Fund subsidies for telephone service in rural areas with subsidies for broadband in rural areas.

Like the federal budget negotiations, the never-ending negotiations over USF get bogged down in arguments over distribution: who gets what. Indeed, it's almost exclusively an argument over which companies get what. But federal telecommunications policy is supposed to advance the overall public interest, not just haggle over what corporate interest gets what piece of my pie. Here is a quick take on the biggest strengths and weaknesses of the plan in terms of advancing overall consumer welfare. By "consumer welfare," I mean not just the welfare of the folks receiving subsidized services, but also the welfare of the majority who are paying a 15 percent charge on interstate phone services to fund the USF.

BIGGEST STRENGTHS

Fixed-term commitment: Rural phone subsidies have become a perpetual entitlement with no definition of when the subsidies can end because the problem is considered solved. The ABC plan proposes a 10-year commitment to rural broadband subsidies. By 2022 the FCC should assess whether any further high-cost universal service program is needed. This idea remedies a significant deficiency in the current high-cost subsidy program, which doesn't even have outcome goals or measures. (That's why I like to sing the final verse from "And the Money Kept Rolling In" from Evita when I talk about universal service. Free State Foundation President Randy May asked me for an encore of this at the end of the foundation's July 13 program on universal service, available here.)

Intercarrier compensation: "Intercarrier compensation" refers to the per-minute charges communications companies pay when they hand off phone traffic to each other. The plan proposes to ramp down all intercarrier charges to a uniform rate of $0.0007/minute. Economists who study telecommunications have pointed out for decades that high per-minute charges reduce consumer welfare by discouraging consumers from communicating as much as they otherwise would. MIT economist Jerry Hausman, in a paper prepared for the filing, estimates that low, uniform intercarrier charges would increase consumer welfare by about $9 billion annually.

Legacy obligations: Public utility regulation traditionally forced regulated companies to offer certain services or serve certain markets at a loss, then charge profitable customers higher prices to cover the losses. Judge Richard Posner referred to this opaque practice as "Taxation by Regulation": the customers paying inflated prices get "taxed" to accomplish a public purpose, but they don't know it. Some of these obligations continue today as federal requirements applied to "Eligible Telecommunications Carriers" or state "Carrier of Last Resort" obligations. The plan would remove these obligations for companies that are not receiving USF subsidies.

BIGGEST WEAKNESSES

Definition of broadband: The plan would continue to inflate the cost of rural broadband subsidies by defining "broadband" as 4 megabytes per second download and 768 kilobytes per second upload. This means 3G wireless, satellite, and some wireless Internet service providers do not count as "broadband." This decision more than doubles the number of households considered "unserved" and rules out some lower-cost technologies. Jerry Brito and I have written extensively about both the economics and the legality of this. Interestingly, the ABC coalition's legal white paper arguing that the commission has legal authority to adopt the plan makes no effort to show that the commission has authority to subsidize 4 mbps broadband; it only shows the commission has authority to subsidize some form of broadband.

Alternative cost technology threshold: The plan includes an "alternative cost technology" threshold that allows substitution of satellite broadband for customers who would cost more than $256/month to serve. Inclusion of a threshold is actually a strength. But the $256/month figure is way too high. Satellite broadband with speeds of 1-2 mbps is now available for $60 – $110 per month. Consumers who pay a 15 percent surcharge on their local phone bills to fund USF should not be expected to provide a subsidy of more than $200 per month.

Mobility: The plan appears to advocate subsidies for mobile broadband service in places where it is not currently available. So now the rural entitlement expands to include not just basic broadband service in the home to stay connected, but also a mobile service that a lot of Americans don't even buy unless their employers pay for it! I question whether mobile broadband satisfies the 1996 Telecommunications Act's criteria for universal service subsidies, such as "essential" (not just nice) for education or public safety, or subscribed to by a "substantial majority" of households. These questions should be thoroughly examined before anyone receives subsidies for mobile broadband. At a minimum, households should be eligible for only one broadband subsidy — wireline or mobile — but not both.

July 29, 2011

Net neutrality: the disaster that keeps on giving

On CNET this morning, I argue that delay in approving FCC authority for voluntary incentive auctions is largely the fault of last year's embarrassing net neutrality rulemaking.

On CNET this morning, I argue that delay in approving FCC authority for voluntary incentive auctions is largely the fault of last year's embarrassing net neutrality rulemaking.

While most of the public advocates and many of the industry participants have moved on to other proxy battles (which for most was all net neutrality ever was), Congress has remained steadfast in expressing its great displeasure with the Commission and how it conducted itself for most of 2010.

In the teeth of strong and often bi-partisan opposition, the Commission granted itself new jurisdiction over broadband Internet on Christmas Eve last year. Understandably, many in Congress are outraged by Chairman Julius Genachowski's chutzpah.

So now the equation is simple: while the Open Internet rules remain on the books, Congress is unlikely to give the Chairman any new powers.

House Oversight Committee Chairman Darrell Issa has made the connection explicit, telling reporters in April that incentive auction authority will not come while net neutrality hangs in the air. There's plenty of indirect evidence as well.

The linkage came even more sharply into focus as I was writing the article. On Tuesday, Illinois Senator Mark Kirk offered an amendment to Sen. Reid's budget proposal, which would have prohibited the FCC from adding neutrality restrictions on VIA auctions. On Wed., Sen. Dean Heller wrote a second letter to the Chairman, this one signed by several of his colleagues, encouraging the Commission to follow President Obama's advice and consider the costs and benefits of the Open Internet rules before implementing them.

Yesterday, key House Committee chairmen initiated an investigation into the process of the rulemaking, raising allegations of improper collusion between the White House and the agency, and of a too-cozy relationship between some advocacy groups and members of the Commission.

All this for rules that have yet to take effect, and which face formidable legal challenges.

The Chairman needs a political solution to a problem largely of his own creation. But up until now, there's little indication that either the FCC or the White House understand the nature of the challenge. This year, we've had a steady drumbeat of spectrum crisismongering, backed up by logical policy and economic arguments in favor of the VIAs.

While some well-respected economists aren't convinced VIAs are the best solution to a long history of spectrum mismanagement, for the most part the business case has been made. But the FCC keeps making it anyway.

Meanwhile, the net neutrality problem isn't going away. Mobile users are enjoying their endless wireless Woodstock summer, marching exuberantly toward oblivion, faster and in greater numbers all the time.

Silicon Valley better save us. Because the FCC, good intentions aside, isn't even working on the right problem.

July 28, 2011

Are Social Networks Essential Facilities?

That's the question I take up in my latest Forbes column, "The Danger Of Making Facebook, LinkedIn, Google And Twitter Public Utilities." I note the rising chatter in the blogosphere about the potential regulation of social networking sites, including Facebook and Twitter. In response, I argue:

public utilities are, by their very nature, non-innovative. Consumers are typically given access to a plain vanilla service at a "fair" rate, but without any incentive to earn a greater return, innovations suffers. Of course, social networking sites are already available to everyone for free! And they are constantly innovating. So, it's unclear what the problem is here and how regulation would solve it.

I don't doubt that social networking platforms have become an important part of the lives of a great many people, but that doesn't mean they are "essential facilities" that should treated like your local water company. These are highly dynamic networks and services built on code, not concrete. Most of them didn't even exist 10 years ago. Regulating them would likely drain the entrepreneurial spirit from this sector, discourage new innovation and entry, and potentially raise prices for services that are mostly free of charge to consumers. Social norms, public pressure, and ongoing rivalry will improve existing services more than government regulation ever could.

Read my full essay for more.

Netflix Relief Fund

July 26, 2011

Woodrow Hartzog on clickwrap and browsewrap agreements

On the podcast this week, Woodrow Hartzog, Assistant Professor at Samford University's Cumberland School of Law, and a Scholar at the Stanford's Center for Internet and Society, discusses his new paper in Communications Law and Policy entitled, The New Price To Play: Are Passive Online Media Users Bound By Terms of Use? By simply browsing the internet, one can be obligated by a "terms of use" agreement displayed on a website. These agreements, according to Hartzog, aren't always displayed where a user can immediately read them, and they often contain complicated legalese. Web browsers can be affected unfavorably by these agreements, particularly when it comes to copyright and privacy issues. Hartzog evaluates what the courts are doing about this, and discusses the different factors that could determine the enforceability of these agreements, including the type of notice a web browser receives.

Related Links

The New Price to Play: Are Passive Online Media Users Bound by Terms of Use? , by Hartzog

Woodrow Hartzog's blog

"Browsewrap Agreements: The Contract You Never See", Austin Technology Law Blog

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we'd like to ask you to comment at the webpage for this episode on Surprisingly Free. lso, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

July 25, 2011

FairSearch's Non-Sequitur Response

[By Geoffrey Manne and Joshua Wright. Cross-posted at TOTM]

Our search neutrality paper has received some recent attention. While the initial response from Gordon Crovitz in the Wall Street Journal was favorable, critics are now voicing their responses. Although we appreciate FairSearch's attempt to engage with our paper's central claims, its response is really little more than an extended non-sequitur and fails to contribute to the debate meaningfully.

Unfortunately, FairSearch grossly misstates our arguments and, in the process, basic principles of antitrust law and economics. Accordingly, we offer a brief reply to correct a few of the most critical flaws, point out several quotes in our paper that FairSearch must have overlooked when they were characterizing our argument, and set straight FairSearch's various economic and legal misunderstandings.

We want to begin by restating the simple claims that our paper does—and does not—make.

Our fundamental argument is that claims that search discrimination is anticompetitive are properly treated skeptically because: (1) discrimination (that is, presenting or ranking a search engine's own or affiliated content more prevalently than its rivals' in response to search queries) arises from vertical integration in the search engine market (i.e., Google responds to a query by providing not only "10 blue links" but also perhaps a map or video created Google or previously organized on a Google-affiliated site (YouTube, e.g.)); (2) both economic theory and evidence demonstrate that such integration is generally pro-competitive; and (3) in Google's particular market, evidence of intense competition and constant innovation abounds, while evidence of harm to consumers is entirely absent. In other words, it is much more likely than not that search discrimination is pro-competitive rather than anticompetitive, and doctrinal error cost concerns accordingly counsel great hesitation in any antitrust intervention, administrative or judicial. As we will discuss, these are claims that FairSearch's lawyers are quite familiar with.

FairSearch, however, grossly mischaracterizes these basic points, asserting instead that we claim

"that even if Google does [manipulate its search results], this should be immune from antitrust enforcement due to the difficulty of identifying 'bias' and the risks of regulating benign conduct."

This statement is either intentionally deceptive or betrays a shocking misunderstanding of our central claim for at least two reasons: (1) we never advocate for complete antitrust immunity, and (2) it trivializes the very real—and universally-accepted–difficulty of distinguishing between pro- and anticompetitive conduct.

First, we acknowledge the obvious point that as a theoretical matter discrimination can amount to an antitrust violation in some cases under certain specific circumstances—not the least important of which is proof of actual competitive harm. To quote ourselves:

The key question is whether such a bias benefits consumers or inflicts competitive harm. Economic theory has long understood the competitive benefits of such vertical integration; modern economic theory also teaches that, under some conditions, vertical integration and contractual arrangements can create a potential for competitive harm that must be weighed against those benefits . . . . From a policy perspective, the issue is whether some sort of ex ante blanket prohibition or restriction on vertical integration is appropriate instead of an ex post, fact-intensive evaluation on a case-by-case basis, such as under antitrust law. (Manne and Wright, 2011) (emphasis added).

This is not much of a concession. While FairSearch tries to move the goalposts by focusing on a straw man proposition that search bias is categorically immune from antitrust scrutiny, this sleight of hand doesn't accomplish much and reveals what FairSearch is missing. After all, consider that almost every single form of business conduct can be an antitrust violation under some set of conditions! The antitrust laws apply in principle to (that is, do not categorically make immune) horizontal mergers, vertical mergers, long-term contracts, short-term contracts, exclusive dealing, partial exclusive dealing, burning down a rival's factory, dealing with rivals, refusing to dealing with rivals, boycotts, tying contracts, overlapping boards, and all manner of pricing practices. Indeed, it is hard to find categories of business conduct that are outright immune from the antitrust laws. So—we agree: "Search bias" can conceivably be anticompetitive. Unfortunately for FairSearch, we never said otherwise and it's not a very interesting point to discuss.

With that point firmly established, one can return focus to the topic FairSearch painstakingly avoids throughout its response and on which we think the issue really does (and should) turn: Where's the proof of consumer harm?

We make the rather common sense point that when engaging in a case-by-case factual analysis of the competitive effects of business conduct, one should take advantage of what we already know about the class of business practice generally. Along those lines, we noted that the economic literature has extensively analyzed the competitive effects of such discrimination and concluded that in most cases it yields significant efficiencies and is therefore unlikely ex ante to amount to an antitrust violation. Perhaps FairSearch was confused by this argument, though we explicitly frame the choice as one between ex ante categorical regulations and ex post case-by-case analyses, not as one between ex anteprohibitions and "allowing Google free rein to discriminate against competitors," as FairSearch bizarrely claims. This is something akin to claiming a defense attorney demands "immunity" for a client with an alibi rather than the correct outcome under a faithful application of the law. (Although we hasten to add that it's not clear that would be, in fact, anything at all wrong with Google "discriminating against competitors." We're sure its shareholders would be apoplectic if it didn't, in fact).

At any rate, even before we get to the question of whether there is any evidence of consumer harm, we do indeed think it is relevant to any analysis that bias is hard to identify, that one user's "bias" is another user's "relevant search result," that a remedy would be difficult to design and harder to enforce, and that the costs of being wrong are significant. These are not dispositive, nor do we claim they are. But they do underscore another point that FairSearch misses: That harmful search bias would be exceptionally difficult to detect even if it were assumed to exist.

This problem can't be brushed off, and it mirrors the well-known uncertainty at the core of the antitrust enterprise: That a given course of conduct may prove pro-competitive or anticompetitive under differing situations. Former AAG Tom Barnettand current Google critic (representing Expedia) has himself echoed this point, observing that

No institution that enforces the antitrust laws is omniscient or perfect. Among other things, antitrust enforcement agencies and courts lack perfect information about pertinent facts, including the impact of particular conduct on consumer welfare . . . . We face the risk of condemning conduct that is not harmful to competition . . . and the risk of failing to condemn conduct that does harm competition . . .

Barnett further notes that "discerning whether a monopolist's actions have hurt or helped competition can be extremely difficult."

At the same time, FairSearch does not dispute that significant efficiencies can arise from vertical integration in the search engine market. Rather, FairSearch distracts itself from this substantial problem in its response by instead quibbling over the factual details of our shelf space analogy and arguing incoherently that Google's conduct violates antitrust laws merely because it deprives rivals of scale. But here FairSearch misses the mark in telling ways.

First, on the shelf space analogy: As we've discussed numerous times (e.g., here and here) the shelf space analogy illustrates that promotional arrangements and vertical integration can have obvious benefits; for example, such arrangements can align incentives for product promotion between up- and downstream actors, thereby increasing output and consumer welfare. FairSearch confuses the analogy by focusing upon the fact that supermarkets, unlike Google, certainly do not have monopoly power. To borrow a quote, we do not think that means what FairSearch thinks it means. That competitors without market power in highly competitive markets engage in a challenged conduct just as competitors with it do might suggest to the astute antitrust observer that the conduct has real competitive merit unrelated to any exclusionary effect. Moreover, the shelf space analogy is designed to highlight the essential fact that because a firm is large (or has a large market share) does not mean its conduct does not also generate consumer benefits! As the court in Berkey Photo noted:

[A] large firm does not violate § 2 simply by reaping the competitive rewards attributable to its efficient size, nor does an integrated business offend the Sherman Act whenever one of its departments benefits from association with a division possessing a monopoly in its own market. So long as we allow a firm to compete in several fields, we must expect it to seek the competitive advantages of its broad-based activity – more efficient production, greater ability to develop complementary products, reduced transaction costs, and so forth. These are gains that accrue to any integrated firm, regardless of its market share, and they cannot by themselves be considered uses of monopoly power.

The point of the analogy, which FairSearch entirely misses yet does not deny, is that these arrangements yield pro-competitive efficiencies – and that these efficiencies are not a function of monopoly power but rather of efficient—even innovative—forms of business organization.

Similarly, FairSearch's arguments about scale in the search engine market are unpersuasive and represent a serious misunderstanding of the market dynamics. FairSearch seems to argue that increased access to ad space leads to higher profits, and that Google, as the recipient of this windfall, can accordingly out-buy its rivals, implying that, eventually, they will simply wither on the vine as Google ends up possessing all the money in the world. Or something like that.

Of course this argument is outlandish on its face. Microsoft, which has overwhelming resources, is one of Google's closest competitors and certainly cannot be easily out-bought. Moreover, the initial claim itself is weak because (1) many advertisers multi-home, dissipating any efficiency that increased access would yield, and (2) advertisers pay per click – because search engines with fewer users necessarily initiate fewer clicks, advertising may be cheaper on smaller platforms. So, while the value on two different size platforms may diverge, so do prices. Merely asserting that one has more value and therefore higher prices is not sufficient to demonstrate divergence on the relevant dimension; rather these factors could – and likely do – increase commensurately.

The most glaring flaw in FairSearch's argument, however, is its failure to present any evidence whatsoever of competitive harm. In demonstrating a Section 2 violation, the burden is on the plaintiff in the first instance to make a showing of harm to competition. Rather than engage in this effort itself, FairSearch summarily dismisses our argument because we "do not seek to marshal evidence that Google does not manipulate search results to harm competition." However, this is not our burden to bear. We repeat: FairSearch fails to present any evidence of its own case-in-chief; it relies on an economically incoherent and premature dismissal of claims we did not make (categorical immunity for "bias") in making its own naked assertions.

Note FairSearch's remarkable sleight of hand here – it (1) attempts to shift the burden of proof to us while (2) simultaneously equating bias with harm to consumer welfare, in an attempt to further simplify its burden. Bias, however, does not implicate harm to consumers, as FairSearch suggests–nor has harmful bias ever even been convincingly demonstrated.

FairSearch asserts that research has shown that Google often ranks its own results above those of rivals "without any apparent relationship to the quality of these Google sites as compared to competing sites." However, Professor Ben Edelman's study, upon which FairSearch relies for this assertion, is a far cry from the sort of rigorous analysis Mr. Barnett called for in Section 2 cases as the Attorney General ("there seems to be consensus that we should prohibit unilateral conduct only where it is demonstrated through rigorous economic analysis to harm competition and thereby to harm consumer welfare"). Indeed, comparing 32 hand-picked search queries across search engines is hardly an adequate sample size or methodology for these purposes – and certainly does not suggest that Google is entirely unconcerned with the quality of its results. In any event, so-called "bias," even if proven, may at most represent harm to rivals – and this is not the relevant metric of antitrust injury. Furthermore, as noted above, bias offers significant benefits and more often than not enhances consumer welfare.

Overall, FairSearch's critique of our paper is weak and crucially flawed. FairSearch relies upon a bald assertion that bias exists to equate that bias to consumer harm while conceding (but ignoring) that vertical integration may introduce significant efficiencies in the search engine market. It tries to wish these efficiencies out of existence by erroneously claiming that monopoly power in the downstream market forecloses that possibility. The basic economic analysis of vertical integration says otherwise. But most essentially, FairSearch simply offers no evidence at all of consumer harm. By alleging antitrust injury, FairSearch has the burden of demonstrating competitive harm in the first instance. This burden is especially high in the search engine market, where, in contrast to the dearth of evidence of consumer harm, evidence of innovation abounds.

All of which is to say, our original argument bears repeating: Claims of anticompetitive conduct should be viewed with serious skepticism when there is abundant evidence of consumer benefits, in the form of innovation and competition, and zero evidence of consumer harm. If FairSearch wishes to mount a credible challenge to our analysis they have a lot more work to do.

How Do-Not-Track is Like Inconceivable

Do-Not-Track is not inconceivable itself. It's like the word "inconceivable" in the movie The Princess Bride. I do not think it means what people think it means—how it is meant to work and how it is likely to offer poor results.

Take Mike Swift's reporting for MercuryNews.com on a study showing that online advertising companies may continue to follow visitors' Web activity even after those visitors have opted out of tracking.

"The preliminary research has sparked renewed calls from privacy groups and Congress for a 'Do Not Track' law to allow people to opt out of tracking, like the Do Not Call list that limits telemarketers," he writes.

If this is true, it means that people want a Do Not Track law more because they have learned that it would be more difficult to enforce.

That doesn't make sense … until you look at who Swift interviewed for the article: a Member of Congress who made her name as a privacy regulation hawk and some fiercely committed advocates of regulation. These people were not on the fence before the study, needless to say. (Anne Toth of Yahoo! provides the requisite ounce of balance, but she defends her company and does not address the merits or demerits of a Do-Not-Track law.)

Do-Not-Track is not inconceivable. But the study shows that its advocates are not conceiving the complexities and drawbacks of a regulatory approach rather than individually tailored blocking of unwanted tracking, something any Internet user can do right now using Tracking Protection Lists.

July 21, 2011

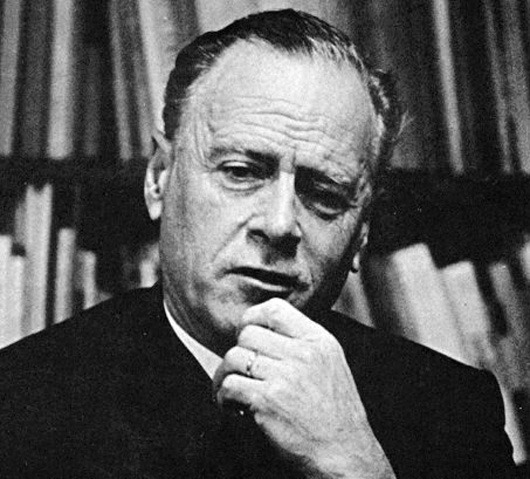

Marshall McLuhan at 100: Excerpts from his Playboy Interview

I have always struggled with the work of media theorist Marshall McLuhan. I find it to be equal parts confusing and compelling; it's persuasive at times and then utterly perplexing elsewhere. I just can't wrap my head around him and yet I can't stop coming back to him.

I have always struggled with the work of media theorist Marshall McLuhan. I find it to be equal parts confusing and compelling; it's persuasive at times and then utterly perplexing elsewhere. I just can't wrap my head around him and yet I can't stop coming back to him.

Today would have been his 100th birthday. He died in 1980, but he's just as towering of a figure today as he was during his own lifetime. His work is eerily prescient and speaks to us as if written yesterday instead of decades ago. Take, for example, McLuhan's mind-blowing 1969 interview with Playboy. [PDF] The verse is awe-inspiring, but much of the substance is simply impenetrable. Regardless, it serves as perhaps the best introduction to McLuhan's work. I strongly encourage you to read the entire thing. The questions posed by interviewer Eric Norden are brilliant and bring out the best in McLuhan.

I was re-reading the interview while working on a chapter for my next book on Internet optimism and pessimism, a topic I've spent a great deal of time pondering here in the past. Toward the end of the interview, McLuhan is asked by Norden to respond to some of his critics. McLuhan responds in typically brilliant, colorful fashion:

I don't want to sound uncharitable about my critics. Indeed, I appreciate their attention. After all, a man's detractors work for him tirelessly and for free. It's as good as being banned in Boston. But as I've said, I can understand their hostile attitude toward environmental change, having once shared it. Theirs is the customary human reaction when confronted with innovation: to flounder about attempting to adapt old responses to new situations or to simply condemn or ignore the harbingers of change — a practice refined by the Chinese emperors, who used to execute messengers bringing bad news. The new technological environments generate the most pain among those least prepared to alter their old value structures. The literati find the new electronic environment far more threatening than do those less committed to literacy as a way of life. When an individual or social group feels that its whole identity is jeopardized by social or psychic change, its natural reaction is to lash out in defensive fury. But for all their lamentations, the revolution has already taken place.

Moreover, as he points out in another portion of the interview, "Resenting a new technology will not halt its progress." This reflects the powerful technological determinism at work in McLuhan's work that earned him much scorn from his critics. There was a fatalism about his views that rubbed many the wrong way. That tension remains alive and well in debates between Internet optimists and pessimists today.

But what is so interesting about the interview is the next portion of the exchange in which Norden gets McLuhan to break away from his typically fatalistic "I'm-just-the-messenger" narrative and instead actually tell us how he feels about the technological changes and societal impacts he describes so colorfully. His response is terrifically interesting but somewhat schizophrenic. First, he says:

PLAYBOY: You've explained why you avoid approving or disapproving of this revolution in your work, but you must have a private opinion. What is it?

McLUHAN: I don't like to tell people what I think is good or bad about the social and psychic changes caused by new media, but if you insist on pinning me down about my own subjective reactions as I observe the reprimitivization of our culture, I would have to say that I view such upheavals with total personal dislike and dissatisfaction. I do see the prospect of a rich and creative retribalized society — free of the fragmentation and alienation of the mechanical age — emerging from this traumatic period of culture clash; but I have nothing but distaste for the process of change.

As a man molded within the literate Western tradition, I do not personally cheer the dissolution of that tradition through the electric involvement of all the senses: I don't enjoy the destruction of neighborhoods by high-rises or revel in the pain of identity quest. No one could be less enthusiastic about these radical changes than myself. I am not, by temperament or conviction, a revolutionary; I would prefer a stable, changeless environment of modest services and human scale. TV and all the electric media are unraveling the entire fabric of our society, and as a man who is forced by circumstances to live within that society, I do not take delight in its disintegration.

You see, I am not a crusader; I imagine I would be most happy living in a secure preliterate environment; I would never attempt to change my world, for better or worse. Thus I derive no joy from observing the traumatic effects of media on man, although I do obtain satisfaction from grasping their modes of operation. [...]

The Western world is being revolutionized by the electric media as rapidly as the East is being Westernized, and although the society that eventually emerges may be superior to our own, the process of change is agonizing. I must move through this pain-wracked transitional era as a scientist would move through a world of disease; once a surgeon becomes personally involved and disturbed about the condition of his patient, he loses the power to help that patient. Clinical detachment is not some kind of haughty pose I affect — nor does it reflect any lack of compassion on my part; it's simply a survival strategy. The world we are living in is not one I would have created on my own drawing board, but it's the one in which I must live, and in which the students I teach must live. If nothing else, I owe it to them to avoid the luxury of moral indignation or the troglodytic security of the ivory tower and to get down into the junk yard of environmental change and steam-shovel my way through to a comprehension of its contents and its lines of force — in order to understand how and why it is metamorphosing man.

This sounds like grimly pessimistic and fatalistic stuff. But Norden wisely doesn't let it end there and he points out that much of McLuhan's work suggests a different interpretation or perspective is possible. McLuhan's response is inspiring:

PLAYBOY: Despite your personal distaste for the upheavals induced by the new electric technology, you seem to feel that if we understand and influence its effects on us, a less alienated and fragmented society may emerge from it. Is it thus accurate to say that you are essentially optimistic about the future?

McLUHAN: There are grounds for both optimism and pessimism. The extensions of man's consciousness induced by the electric media could conceivably usher in the millennium, but it also holds the potential for realizing the Anti-Christ — Yeats' rough beast, its hour come round at last, slouching toward Bethlehem to be born. Cataclysmic environmental changes such as these are, in and of themselves, morally neutral; it is how we perceive them and react to them that will determine their ultimate psychic and social consequences. If we refuse to see them at all, we will become their servants. It's inevitable that the world-pool of electronic information movement will toss us all about like corks on a stormy sea, but if we keep our cool during the descent into the maelstrom, studying the process as it happens to us and what we can do about it, we can come through.

Personally, I have a great faith in the resiliency and adaptability of man, and I tend to look to our tomorrows with a surge of excitement and hope. I feel that we're standing on the threshold of a liberating and exhilarating world in which the human tribe can become truly one family and man's consciousness can be freed from the shackles of mechanical culture and enabled to roam the cosmos. I have a deep and abiding belief in man's potential to grow and learn, to plumb the depths of his own being and to learn the secret songs that orchestrate the universe. We live in a transitional era of profound pain and tragic identity quest, but the agony of our age is the labor pain of rebirth.

I expect to see the coming decades transform the planet into an art form; the new man, linked in a cosmic harmony that transcends time and space, will sensuously caress and mold and pattern every facet of the terrestrial artifact as if it were a work of art, and man himself will become an organic art form. There is a long road ahead, and the stars are only way stations, but we have begun the journey. To be born in this age is a precious gift, and I regret the prospect of my own death only because I will leave so many pages of man's destiny — if you will excuse the Gutenbergian image — tantalizingly unread. But perhaps, as I've tried to demonstrate in my examination of the postliterate culture, the story begins only when the book closes.

Cutting through the mind-blowing prose, we can see McLuhan clearly suggesting that, although he's personally uncomfortable with many of the changes that electronic media are bringing about — again, this is 1969! .. amazing! — he remains a believer in the power of human resiliency and adaptability.

This is a key theme — perhaps the key theme — of my forthcoming book on The Case for Internet Optimism. In a nutshell, many pessimists overlook the importance of human adaptability and resiliency. The amazing thing about humans is that we adapt so much better than other mammals. When it comes to technological change, resiliency is hard-wired into our genes. We learn how to use the new tools given to us and make them part of our lives and culture in a creative and constructive way such that we evolve and prosper.

Thus, while I still can't wrap my pea-brain around what McLuhan is talking about when he refers to man's ability "to learn the secret songs that orchestrate the universe," I certainly share his "deep and abiding belief in man's potential to grow and learn"!

July 20, 2011

This Would Be a Good Time to Not be Evil

Daily news service TechLawJournal (subscription) reports that the U.S. District Court (DC) has granted summary judgment to the National Security Agency in EPIC v. NSA, a federal Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) case regarding the Electronic Privacy Information Center's request for records regarding Google's relationship with the NSA.

EPIC requested a wide array of records regarding interactions between Google and the NSA dealing with information security. Reports TLJ:

The NSA responded that it refused to confirm or deny whether it had a relationship with Google, citing Exemption 3 of FOIA (regarding records "specifically exempted from disclosure by statute") and Section 6 of the National Security Agency Act of 1959 (which prohibits disclose of information about the NSA).

The FOIA merits of EPIC's suit are one thing. It's another for Google to have an intimate relationship with a government agency this secretive.

This would be a good time to not be evil. Google should either sever ties with the NSA or be as transparent (or more) than federal law would require the NSA to be in the absence of any special protection against disclosure.

July 19, 2011

The Bono-Mack Bill & Giving APA Authority to the FTC to Redefine "PII"

A month ago, Rep. Mary Bono Mack introduced a bill (and staff memo) "To protect consumers by requiring reasonable security policies and procedures to protect data containing personal information, and to provide for nationwide notice in the event of a security breach." These are perhaps the two least objectionable areas for legislating "on privacy" and there's much to be said for both concepts in principle. Less clear-cut is the bill's data minimization requirement for the retention of personal information.

But as I finally get a chance to look at the bill on the eve of the July 20 Subcommittee markup, I note one potentially troubling procedural aspect of the bill: giving the FTC authority to redefine PII without the procedural safeguards that normally govern the FTC's operations. The scope of this definition would be hugely important in the future, both because of the security, breach notification and data minimization requirements attached to it, and because this definition would likely be replicated in future privacy legislation—and changes in to this term in one area would likely follow in others.

The bill (p. 28) provides a fairly common-sensical definition of "personal information":

an individual's first name or initial and last name, or address, or phone number, in combination with any 1 or more of the following data elements for that individual… [including a social security number, driver's license or other identity number, financial account number, etc.]

Then the bill then gives the FTC the authority to redefine PII in the future. The bill limits that authority to situations where:

(i) … such modification is necessary … as a result of changes in technology or practices and will not unreasonably impede technological innovation or otherwise adversely affect interstate commerce; and

(ii) … if the Commission determines that access to or acquisition of the additional data elements in the event of a breach of security would create an unreasonable risk of identity theft, fraud, or other unlawful conduct and that such modification will not unreasonably impede technological innovation or otherwise adversely affect interstate commerce.

This is an admirable attempt to make the statute flexible and forward-looking without giving the FTC carte blanche to redefine "PII"—easily the single most important term in when it comes to regulating the flow of data in our information economy. But I fear even these prudent measures may not be enough if the FTC can use the streamlined Administrative Procedures Act (APA) rulemaking process. Yes, of course, that's the same process used by most federal agencies, but it's not what the FTC generally uses—and for good reason. Commissioner Kovacic explained "Mag-Moss" in his 2010 Senate testimony on this issue:

Magnuson-Moss rulemaking, as this authority is known, requires more procedures than those needed for rulemaking pursuant to the Administrative Procedure Act. These include two notices of proposed rulemaking, prior notification to Congress, opportunity for an informal hearing, and, if issues of material fact are in dispute, cross-examination of witnesses and rebuttal submissions by interested persons.

Kovacic isn't against all grants of APA authority to the FTC:

In addition, over the past 15 years, there have been a number of occasions where Congress has identified specific consumer protection issues requiring legislative and regulatory action. In those specific instances, Congress has given the FTC authority to issue rules using APA rulemaking procedures….

Except where Congress has given the FTC a more focused mandate to address particular problems, beyond the FTC Act's broad prohibition of unfair or deceptive acts or practices, I believe that it is prudent to retain procedures beyond those encompassed in the APA [i.e., Magnuson-Moss].

Kovacic's cautiousness about this largely stems from his desire to protect the FTC from repeating the over-reach in the late 1970s that caused even the Washington Post to brand the agency the "National Nanny" and a heavily Democratic Congress to try to briefly shut down the agency, heavily slash its funding and require additional procedural safeguards—a history I've written about here and here, and the subject of a PFF event I ran in April 2010. (Of course, Howard Beales wrote the definitive history of this saga.) Kovacic continues:

The lack of a more focused mandate and direction from Congress, reflected in legislation with relatively narrow tailoring, could result in the FTC undertaking initiatives that ultimately arouse Congressional ire and lead to damaging legislative intervention in the FTC's work…. Through specific, targeted grants of APA rulemaking authority, Congress makes a credible commitment not to attack the Commission when the agency exercises such authority

So what might Commissioner (and former FTC Chairman) Kovacic say about Rep. Bono-Mack's bill? Unfortunately, he's retiring from the Commission in September, so we may not actually hear an official answer from him (and FTC Commissioners generally don't opine about pending legislation anyway unless asked to do so). But I'll wager he'd applaud the requirements for redefinition and, in principle, he'd be open to giving the FTC APA authority in a narrow area. But I think he'd wonder whether redefining a term so critical as "personal information" is really a "specific", "targeted" or "focused" given what's at stake—in particular, the data minimization requirement, which could swallow much of online data collection if "personal information" were defined too broadly.

Rep. Bono-Mack is clearly well aware of these dangers, given the evident thought that went into writing the twin requirements for redefinition I quoted above. But it's well worth asking whether they'll be enough to prevent abuse of the power to redefine PII. At the very least, this seems like a question worth considering very, very carefully before the bill moves forward.

Other thoughts?

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower