Adam Thierer's Blog, page 122

July 8, 2011

★ Vivek Wadhwa on High-Tech's "Best Regulator"

Vivek Wadhwa, who is affiliated with Harvard Law School and is director of research at Duke University's Center for Entrepreneurship, has a terrific column in today's Washington Post warning of the dangers of government trying to micromanage high-tech innovation and the Digital Economy from above.

Vivek Wadhwa, who is affiliated with Harvard Law School and is director of research at Duke University's Center for Entrepreneurship, has a terrific column in today's Washington Post warning of the dangers of government trying to micromanage high-tech innovation and the Digital Economy from above.

For reasons I have never been able to understand, the Washington Post uses different headlines for its online opeds versus its print edition. That's a shame, because while I like the online title of Wadhwa's essay, "Uncle Sam's Choke-Hold on Innovation," the title in the print edition is better: "Google, Twitter and the Best Regulator." By "best regulator" Wadhwa means the marketplace, and this is a point we have hammered on here at the TLF relentlessly: Contrary to what some critics suggest, the best regulator of "market power" is the market itself because of the way it punishes firms that get lethargic, anti-innovative, or just plain cocky. Wadhwa notes:

The technology sector moves so quickly that when a company becomes obsessed with defending and abusing its dominant market position, countervailing forces cause it to get left behind. Consider: The FTC spent years investigating IBM and Microsoft's anti-competitive practices, yet it wasn't government that saved the day; their monopolies became irrelevant because both companies could not keep pace with rapid changes in technology — changes the rest of the industry embraced. The personal-computer revolution did IBM in; Microsoft's Waterloo was the Internet. This — not punishment from Uncle Sam — is the real threat to Google and Twitter if they behave as IBM and Microsoft did in their heydays.

Quite right. I've discussed the Microsoft and IBM antitrust sagas many times here before. In particular, see my 2009 review of Gary Reback's book on antitrust and high-tech and my recent essay on "Libertarianism & Antitrust: A Brief Comment." I've also commented on the FTC's look at Twitter and Google in my recent essays, "Twitter, the Monopolist? Is this Tim Wu's "Threat Regime" In Action?" and "The Question of Remedies in a Google Antitrust Case."

The crucial points I have tried to get across in these essays, as well as all my essays countering the modern cyber-progressives," is that high-tech market power concerns are ultimately better addressed by voluntary, spontaneous, bottom-up, marketplace responses than by coerced, top-down, governmental solutions. Moreover, the decisive advantage of the market-driven approach to correcting market or "code failure" comes down to the rapidity and nimbleness of those responses, especially in markets built upon bits instead of atoms.

That's why Wadhwa's insight — that "the technology sector moves so quickly that when a company becomes obsessed with defending and abusing its dominant market position, countervailing forces cause it to get left behind" — is so cogent. We're not talking about markets like steel and corn here. Things move much, much more quickly when bits and code and are the foundations of what Tim Wu calls "information empires." There's no doubt that some companies will gain scale and even "power" quickly in our new Digital Economy, but they can also lose it in the blink of an eye.

The best modern example that I've documented here before is AOL. It's easy to forget now, but just a short decade ago, academics and regulators were in a tizzy over Big Bad AOL. And why not? After all, 25 million subscribers were willing to pay $20 per month to get a guided tour of AOL's walled garden version of the Internet. And then AOL and Time Warner announced a historic mega-merger that had some predicting the rise of "new totalitarianisms" and corporate "Big Brother."

But the deal quickly went off the rails. By April 2002, just two years after the deal was struck, AOL-Time Warner had already reported a staggering $54 billion loss. By January 2003, losses had grown to $99 billion. By September 2003, Time Warner decided to drop AOL from its name altogether and the deal continued to slowly unravel from there. In a 2006 interview with the Wall Street Journal, Time Warner President Jeffrey Bewkes famously declared the death of "synergy" and went so far as to call synergy "bullsh*t"! In early 2008, Time Warner decided to shed AOL's dial-up service and then to spin off AOL entirely. Looking back at the deal, Fortune magazine senior editor at large Allan Sloan called it the "turkey of the decade." The formal divorce between the two firms took place in 2008. Further deconsolidation followed for Time Warner, which spun off its cable TV unit and various other properties.

Meanwhile, AOL has lost its old dial-up business and walled garden empire and is still struggling to reinvent itself as an advertising company. It's about the last company on anybody's lips when we talk about tech titans today. What an epic tale of creative destruction! That all happened is less than 10 years! And yet, again, a decade ago, tech pundits and cyberlaw intellectuals like Larry Lessig were penning entire books about the ominous threat posed by the AOL walled garden model of Internet governance.

Lessig's myopia was based on an inherent techno-pessimism I have discussed and critiqued in my Next Digital Decade book chapter, "The Case for Internet Optimism, Part 2 – Saving the Net From Its Supporters." Countless Ivory Tower cyber-academics today adopt a static view of markets and market problems. This "static snapshot" crowd gets so worked up about short term spells of "market power" – which usually don't represent serious market power at all – that they call for the reordering of markets to suit their tastes. Sadly, they sometimes do this under the banner of "Internet freedom," claiming that techno-cratic elites can "free" consumers from the supposed tyranny of the marketplace.

In reality, that vision wraps markets in chains and ultimately leaves consumers worse off by stifling innovation and inviting in ham-handed regulatory edicts and bureaucracies to plan this fast-paced sector of our economy. Importantly, that vision ignores the deadweight losses associated with expanding government red tape and bureaucracy as well as the very real danger of "regulatory capture" that exists anytime Washington decides to get cozy with a major sector of the economy.

As Wadhwa correctly concludes, "Government has no place in this technology jungle." I wish other academics and tech pundits would heed that warning.

July 7, 2011

The Social Science Debate over Violent Video Games Will Never End

NPR science correspondent Shankar Vedantam had a great spot on NPR's Morning Edition today about the disputes among social scientists over the impact of violent video games on kids. ["It's A Duel: How Do Violent Video Games Affect Kids?"] You won't be surprised to hear I wholeheartedly agree with Texas A&M psychologist Chris Ferguson, who noted in the spot:

Ferguson says it's easy to think senseless video game violence can lead to senseless violence in the real world. But he says that's mixing up two separate things. "Many of the games do have morally objectionable material and I think that is where a lot of the debate on this issue went off the rails," he said. "We kind of mistook our moral concerns about some of these video games, which are very valid — I find many of the games to be morally objectionable — and then assumed that what is morally objectionable is harmful."

I've written about Ferguson's work and these issues more generally many times over through the years here at the TLF. Here are some of the most relevant essays:

Video Games, Media Violence & the Cathartic Effect Hypothesis

More on Monkey See-Monkey Do Theories about Media Violence & Real-World Crime

Video Games, Free Speech & the Lunacy of "Ecogenerism"

Video Games and "Moral Panic"

Video Games, Violence, & Social "Science": Another Day, Another Fight

Do video games create cop killers?

In these essays, I've tried to make a couple of key points about the social science literature on "media effects" theory:

(1) Lab studies by psychology professors and students are not representative of real-world behavior/results. Indeed, lab experiments are little more than artificial constructions of reality and of only limited value in gauging the impact of violently-themed media on actual human behavior.

(2) Real-world data trends likely offer us a better indication of the impact of media on human behavior over the long-haul. And all those trends show encouraging signs of improvement even as video game consumption among youth and adults increases.

(3) Correlation does not necessarily equal causation. Of course, whether we are talking about those artificial lab experiments or the real-world data sets, we must always keep this first principle of statistical analysis in mind.

(4) Finally, it's worth reconsidering whether more weight should be given to the "cathartic effect hypothesis" in these debates.

A bit more on this final point since I feel quite passionately about it…

The battle over media effect theory goes all the way back to the great Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle. While Plato thought the media of his day (poetry, plays & music) had a deleterious impact on culture and humanity, Aristotle took a very different view. Indeed, most historians believe it was Aristotle who first used the term katharsis when discussing the importance of Greek tragedies, which often contained violent overtones and action. He suggested that these tragedies helped the audience, "through pity and fear effecting the proper purgation of these emotions." In Part IV of his Poetics, Aristotle spoke highly of tragedies that used provocative or titillating storytelling to its fullest effect:

Tragedy is an imitation not only of a complete action, but of events inspiring fear or pity. Such an effect is best produced when the events come on us by surprise; and the effect is heightened when, at the same time, they follow as cause and effect. The tragic wonder will then be greater than if they happened of themselves or by accident; for even coincidences are most striking when they have an air of design. We may instance the statue of Mitys at Argos, which fell upon his murderer while he was a spectator at a festival, and killed him. Such events seem not to be due to mere chance. Plots, therefore, constructed on these principles are necessarily the best.

And for me, that remains the best explanation for how humans process dramatic depictions of violence and tragedy. We humans are unique among all mammals in our ability to adapt to changes in our environment and to process new and different forms of content and culture. We process. We learn. We assimilate. We adapt. Thus, we can enjoy the "tragic wonder" of watching a violent Greek drama or playing a violent video game without running for the kitchen to find a knife to plunge into somebody's back. We can separate fantasy from reality and we do so every day of our lives.

Yet, many social scientists today, echoing Plato, continue to search for proof that the alternative is true and that depictions of violence on the stage or screen will have a direct and quite deleterious impact on human behavior. They subscribe to the "monkey see-monkey do" theory of media effects. Again, I think that's utterly bogus and flatly contradicted by real-world facts. After all, if there was anything to their theories, shouldn't it have shown up sometime, somewhere in real-world data trends by now?

Still, don't expect this debate to ever end. Just wait till virtual reality technologies go mainstream! Oh boy, now that will have the "monkey see-monkey do" crowd whipped into a lather. I look forward to the debate (and to playing those VR games with my kids!)

★ The Social Science Debate over Violent Video Games Will Never End

NPR science correspondent Shankar Vedantam had a great spot on NPR's Morning Edition today about the disputes among social scientists over the impact of violent video games on kids. ["It's A Duel: How Do Violent Video Games Affect Kids?"] You won't be surprised to hear I wholeheartedly agree with Texas A&M psychologist Chris Ferguson, who noted in the spot:

Ferguson says it's easy to think senseless video game violence can lead to senseless violence in the real world. But he says that's mixing up two separate things. "Many of the games do have morally objectionable material and I think that is where a lot of the debate on this issue went off the rails," he said. "We kind of mistook our moral concerns about some of these video games, which are very valid — I find many of the games to be morally objectionable — and then assumed that what is morally objectionable is harmful."

I've written about Ferguson's work and these issues more generally many times over through the years here at the TLF. Here are some of the most relevant essays:

Video Games, Media Violence & the Cathartic Effect Hypothesis

More on Monkey See-Monkey Do Theories about Media Violence & Real-World Crime

Video Games, Free Speech & the Lunacy of "Ecogenerism"

Video Games and "Moral Panic"

Video Games, Violence, & Social "Science": Another Day, Another Fight

Do video games create cop killers?

In these essays, I've tried to make a couple of key points about the social science literature on "media effects" theory:

(1) Lab studies by psychology professors and students are not representative of real-world behavior/results. Indeed, lab experiments are little more than artificial constructions of reality and of only limited value in gauging the impact of violently-themed media on actual human behavior.

(2) Real-world data trends likely offer us a better indication of the impact of media on human behavior over the long-haul. And all those trends show encouraging signs of improvement even as video game consumption among youth and adults increases.

(3) Correlation does not necessarily equal causation. Of course, whether we are talking about those artificial lab experiments or the real-world data sets, we must always keep this first principle of statistical analysis in mind.

(4) Finally, it's worth reconsidering whether more weight should be given to the "cathartic effect hypothesis" in these debates.

A bit more on this final point since I feel quite passionately about it…

The battle over media effect theory goes all the way back to the great Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle. While Plato thought the media of his day (poetry, plays & music) had a deleterious impact on culture and humanity, Aristotle took a very different view. Indeed, most historians believe it was Aristotle who first used the term katharsis when discussing the importance of Greek tragedies, which often contained violent overtones and action. He suggested that these tragedies helped the audience, "through pity and fear effecting the proper purgation of these emotions." In Part IV of his Poetics, Aristotle spoke highly of tragedies that used provocative or titillating storytelling to its fullest effect:

Tragedy is an imitation not only of a complete action, but of events inspiring fear or pity. Such an effect is best produced when the events come on us by surprise; and the effect is heightened when, at the same time, they follow as cause and effect. The tragic wonder will then be greater than if they happened of themselves or by accident; for even coincidences are most striking when they have an air of design. We may instance the statue of Mitys at Argos, which fell upon his murderer while he was a spectator at a festival, and killed him. Such events seem not to be due to mere chance. Plots, therefore, constructed on these principles are necessarily the best.

And for me, that remains the best explanation for how humans process dramatic depictions of violence and tragedy. We humans are unique among all mammals in our ability to adapt to changes in our environment and to process new and different forms of content and culture. We process. We learn. We assimilate. We adapt. Thus, we can enjoy the "tragic wonder" of watching a violent Greek drama or playing a violent video game without running for the kitchen to find a knife to plunge into somebody's back. We can separate fantasy from reality and we do so every day of our lives.

Yet, many social scientists today, echoing Plato, continue to search for proof that the alternative is true and that depictions of violence on the stage or screen will have a direct and quite deleterious impact on human behavior. They subscribe to the "monkey see-monkey do" theory of media effects. Again, I think that's utterly bogus and flatly contradicted by real-world facts. After all, if there was anything to their theories, shouldn't it have shown up sometime, somewhere in real-world data trends by now?

Still, don't expect this debate to ever end. Just wait till virtual reality technologies go mainstream! Oh boy, now that will have the "monkey see-monkey do" crowd whipped into a lather. I look forward to the debate (and playing those VR games with my kids!)

July 5, 2011

★ Daniel Solove on the tradeoff between privacy and security

On the podcast this week, Daniel Solove, professor at the George Washington University Law School, discusses his new book Nothing to Hide: The False Tradeoff Between Privacy and Security. He suggests that developments in technology do not create a mutually exclusive relationship between privacy and national security. Solove acknowledges the interest government has in maintaining security within our technological world; however, Solove also emphasizes the value of personal privacy rights and suggests that certain procedures, such as judicial oversight on governmental actions, can be implemented to preserve privacy. This oversight may make national security enforcement slightly less effective, but according to Solove, this is a worthwhile tradeoff to ensure privacy protections.

Related Links

Nothing to Hide: The False Tradeoff Between Privacy and Security

I've Got Nothing to Hide' and Other Misunderstandings of Privacy, by Solove

"No rights left to lose: Destroying privacy in name of security in the age of terror", The Daily

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we'd like to ask you to comment at the web page for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

Daniel Solove on the tradeoff between privacy and security

On the podcast this week, Daniel Solove, professor at the George Washington University Law School, discusses his new book Nothing to Hide: The False Tradeoff Between Privacy and Security. He suggests that developments in technology do not create a mutually exclusive relationship between privacy and national security. Solove acknowledges the interest government has in maintaining security within our technological world; however, Solove also emphasizes the value of personal privacy rights and suggests that certain procedures, such as judicial oversight on governmental actions, can be implemented to preserve privacy. This oversight may make national security enforcement slightly less effective, but according to Solove, this is a worthwhile tradeoff to ensure privacy protections.

Related Links

Nothing to Hide: The False Tradeoff Between Privacy and Security

I've Got Nothing to Hide' and Other Misunderstandings of Privacy, by Solove

"No rights left to lose: Destroying privacy in name of security in the age of terror", The Daily

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we'd like to ask you to comment at the web page for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

July 3, 2011

★ FCC v. Pacifica Foundation at 33: Will This Be Its Last an Anniversary?

Today is the 33rd anniversary of the Supreme Court's landmark First Amendment decision, FCC v. Pacifica Foundation. By a narrow 5-4 vote in this 1978 decision, the Court held that the FCC could impose fines on radio and TV broadcasters who aired indecent content during daytime and early evening hours. The Court used some rather tortured reasoning to defend the proposition that broadcast platforms deserved lesser First Amendment treatment than all other media platforms. The lynchpin of the decision was the so-called "pervasiveness theory," which held that broadcast speech was "uniquely pervasive" and an "intruder" in the home, and therefore demanded special, artificial content restrictions.

Back in 2008, when Pacifica turned 30, I penned a 6-part series critiquing the decision and discussing its impact on First Amendment jurisprudence:

Part 1: General overview.

Part 2: A short history of FCC indecency regulation.

Part 3: The misguided logic of the Court's reasoning in Pacifica.

Part 4: How that logic of Pacifica is even more misguided in light of modern developments.

Part 5: A joint editorial on the issue I co-authored with John Morris of Center for Democracy & Technology.

Part 6: Wrap-up and further reading.

In addition to those essays, I brought all my thinking together on this issue in a 2007 law review article, "Why Regulate Broadcasting: Toward a Consistent First Amendment Standard for the Information Age." Importantly, this could be the last year we "celebrate" a Pacifica anniversary. Earlier this week, on the same day it handed down a historical video game free speech win, the Supreme Court announced that next term it will examine the constitutionality of FCC efforts to regulate "indecent" speech on broadcast TV and radio. Here's hoping the Supreme Court takes the sensible step of undoing the unjust regulatory mess they created with Pacifica 33 years ago. Speech is speech is speech. Lawmakers should not be regulating it differently just because it's on TV or radio instead of cable TV, satellite radio or TV, physical media, or the Internet.

Of course, there will always be those who respond by arguing that speech regulation is important because "it's for the children." But raising children, and determining what they watch or listen to, is a quintessential parental responsibility. Personally, I think the most important thing I can do for my children is to preserve our nation's free speech heritage and fight for their rights to enjoy the full benefits of the First Amendment when they become adults. Until then, I will focus on raising my children as best I can. And if because of the existence of the First Amendment they see or hear things I find troubling, offensive or rude, then I will sit down with them and talk to them in the most open, understanding and loving fashion I can about the realities of the world around them. But I don't want anyone else doing that job for me.

Meanwhile, I leave you with The Man himself, George Carlin, the greatest linguistic comic who ever did walk this Earth. I miss George.

FCC v. Pacifica Foundation at 33: Will This Be Its Last an Anniversary?

Today is the 33rd anniversary of the Supreme Court's landmark First Amendment decision, FCC v. Pacifica Foundation. By a narrow 5-4 vote in this 1978 decision, the Court held that the FCC could impose fines on radio and TV broadcasters who aired indecent content during daytime and early evening hours. The Court used some rather tortured reasoning to defend the proposition that broadcast platforms deserved lesser First Amendment treatment than all other media platforms. The lynchpin of the decision was the so-called "pervasiveness theory," which held that broadcast speech was "uniquely pervasive" and an "intruder" in the home, and therefore demanded special, artificial content restrictions.

Back in 2008, when Pacifica turn 30, I penned a 6-part series critiquing the decision and discussing its impact on First Amendment jurisprudence:

Part 1: General overview.

Part 2: A short history of FCC indecency regulation.

Part 3: The misguided logic of the Court's reasoning in Pacifica.

Part 4: How that logic of Pacifica is even more misguided in light of modern developments.

Part 5: A joint editorial on the issue I co-authored with John Morris of Center for Democracy & Technology.

Part 6: Wrap-up and further reading.

In addition to those essays, I brought all my thinking together on this issue in a 2007 law review article, "Why Regulate Broadcasting: Toward a Consistent First Amendment Standard for the Information Age." Importantly, this could be the last year we "celebrate" a Pacifica anniversary. Earlier this week, on the same day it handed down a historical video game free speech win, the Supreme Court announced that next term it will examine the constitutionality of FCC efforts to regulate "indecent" speech on broadcast TV and radio. Here's hoping the Supreme Court takes the sensible step of undoing the unjust regulatory mess they created with Pacifica 33 years ago. Speech is speech is speech. Lawmakers should not be regulating it differently just because it's on TV or radio instead of cable TV, satellite radio or TV, physical media, or the Internet.

Of course, there will always be those who respond by arguing that speech regulation is important because "it's for the children." But raising children, and determining what they watch or listen to, is a quintessential parental responsibility. Personally, I think the most important thing I can do for my children is to preserve our nation's free speech heritage and fight for their rights to enjoy the full benefits of the First Amendment when they become adults. Until then, I will focus on raising my children as best I can. And if because of the existence of the First Amendment they see or hear things I find troubling, offensive or rude, then I will sit down with them and talk to them in the most open, understanding and loving fashion I can about the realities of the world around them. But I don't want anyone else doing that job for me.

Meanwhile, I leave you with The Man himself, George Carlin, the greatest linguistic comic who ever did walk this Earth. I miss George.

July 1, 2011

★ The Question of Remedies in a Google Antitrust Case

It remains unclear how interested the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is in bringing a formal antitrust action against Google, but we at least know that inquiries have been made. I suspect these inquires are far more serious than whatever the agency is fishing for with its new Twitter inquires. After all, as I note in my latest Forbes column, "Google isn't even a teenager yet (having only been founded in September 1998), but the firm's rise has been meteoric and it has made a long list of enemies in the process. Practically every major player in the Digital Economy… is gunning for Google these days, both in the commercial and political marketplace." In this sense, it's not surprising the FTC might take a keen interest in the company with so many competitors complaining.

Still, I just can't find much merit in an antitrust case against Google since, as I noted in my column, "The firm's success seems tied to high quality products that users prefer over rival services. Importantly, barriers to entry are low: there's nothing stopping new entrants from innovating and offering competing online services to match Google."

Regardless, instead of arguing about the merits of an antitrust action against Google, let's consider the more interesting, and I think intractable, question of remedies. Here's what I had to say about that in my Forbes essay:

[possible remedies] include a so-called Federal Search Commission that would monitor search results to achieve "fairness" or "search neutrality." Some academics have also suggested a possible mandatory "right of reply" for companies or consumers if they don't like what a search for their name reveals. This is the equivalent of a Fairness Doctrine for search results.

Another idea, borrowed from Microsoft's antitrust saga in Europe, is a "browser ballot" for specialized search results like maps, stock reports and weather. Just as Microsoft was required by European antitrust officials to offer a "ballot" of alternative browsers before consumers first got online, Google might be forced to show several alternative links for search queries if Google-owned sites are also shown in the results.

Even if ballots could be implemented without reducing the usability of search engines—a tall order—it would be difficult, if not impossible, to incorporate all the choices available to consumers. And if government only chose a few, it would be picking winners and losers. Better to let markets decide.

Making Google's proprietary search algorithm more transparent also sounds great until you realize it would make it easier for spammers and scammers to game search results. Search regulation might also lead to dangerous forms of speech control. Just as the Fairness Doctrine was abused by politicians in the Analog Era, search-tinkering will likely prove too tempting to pass up. For paternalistic policymakers, search regulation could be an opening to do what they've always wanted: "clean up" the Net.

These are just some of the problems with the remedies that have been proposed. Please read some of the essays by Geoff Manne and Josh Wright listed down below for a more in-depth exploration of these issues. Of course, we're still very early in this process and, if a case against Google moves forward, I suspect we'll see a number of other possible remedies suggested.

Regardless, I can't help but have a vague sense of unease about the mere thought of Uncle Sam as Search Czar. Again, from my Forbes essay:

These regulatory solutions would put government bureaucrats in control of the day-to-day management of one of the most dynamic digital technologies ever invented. Treating Google like an essential facility to which all must have equal access on regulated terms would mean subjecting the Internet, still largely free of government control, to public utility-style regulation. It's hard to imagine that regulating search like local sewage service will benefit consumers in the long run. Government simply doesn't have a very good track record of steering markets—especially dynamic, fast-evolving ones like this—in more innovative directions.

I think consumers will be better served by Google and its many competitors spending their time focused on creating innovative new products and services rather than making Washington bureaucrats happy.

Additional Reading from TLF Contributors:

The FTC makes its Google investigation official, now what? – by Geoffrey Manne & Joshua Wright

What's really motivating the pursuit of Google? – by Geoffrey Manne

Search Bias and Antitrust – by Josh Wright

Sacrificing Consumer Welfare in the Search Bias Debate, Part II – by Josh Wright

The Problem of Search Engines as Essential Facilities – by Geoffrey Manne

Why Google probe should worry consumers – by Ryan Radia (in San Jose Mercury News)

Wired on Google's Coming Antitrust Nightmare – by Adam Thierer

The Question of Remedies in a Google Antitrust Case

It remains unclear how interested the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is in bringing a formal antitrust action against Google, but we at least know that inquiries have been made. I suspect these inquires are far more serious than whatever the agency is fishing for with its new Twitter inquires. After all, as I note in my latest Forbes column, "Google isn't even a teenager yet (having only been founded in September 1998), but the firm's rise has been meteoric and it has made a long list of enemies in the process. Practically every major player in the Digital Economy… is gunning for Google these days, both in the commercial and political marketplace." In this sense, it's not surprising the FTC might take a keen interest in the company with so many competitors complaining.

Still, I just can't find much merit in an antitrust case against Google since, as I noted in my column, "The firm's success seems tied to high quality products that users prefer over rival services. Importantly, barriers to entry are low: there's nothing stopping new entrants from innovating and offering competing online services to match Google."

Regardless, instead of arguing about the merits of an antitrust action against Google, let's consider the more interesting, and I think intractable, question of remedies. Here's what I had to say about that in my Forbes essay:

[possible remedies] include a so-called Federal Search Commission that would monitor search results to achieve "fairness" or "search neutrality." Some academics have also suggested a possible mandatory "right of reply" for companies or consumers if they don't like what a search for their name reveals. This is the equivalent of a Fairness Doctrine for search results.

Another idea, borrowed from Microsoft's antitrust saga in Europe, is a "browser ballot" for specialized search results like maps, stock reports and weather. Just as Microsoft was required by European antitrust officials to offer a "ballot" of alternative browsers before consumers first got online, Google might be forced to show several alternative links for search queries if Google-owned sites are also shown in the results.

Even if ballots could be implemented without reducing the usability of search engines—a tall order—it would be difficult, if not impossible, to incorporate all the choices available to consumers. And if government only chose a few, it would be picking winners and losers. Better to let markets decide.

Making Google's proprietary search algorithm more transparent also sounds great until you realize it would make it easier for spammers and scammers to game search results. Search regulation might also lead to dangerous forms of speech control. Just as the Fairness Doctrine was abused by politicians in the Analog Era, search-tinkering will likely prove too tempting to pass up. For paternalistic policymakers, search regulation could be an opening to do what they've always wanted: "clean up" the Net.

These are just some of the problems with the remedies that have been proposed. Please read some of the essays by Geoff Manne and Josh Wright listed down below for a more in-depth exploration of these issues. Of course, we're still very early in this process and, if a case against Google moves forward, I suspect we'll see a number of other possible remedies suggested.

Regardless, I can't help but have a vague sense of unease about the mere thought of Uncle Sam as Search Czar. Again, from my Forbes essay:

These regulatory solutions would put government bureaucrats in control of the day-to-day management of one of the most dynamic digital technologies ever invented. Treating Google like an essential facility to which all must have equal access on regulated terms would mean subjecting the Internet, still largely free of government control, to public utility-style regulation. It's hard to imagine that regulating search like local sewage service will benefit consumers in the long run. Government simply doesn't have a very good track record of steering markets—especially dynamic, fast-evolving ones like this—in more innovative directions.

I think consumers will be better served by Google and its many competitors spending their time focused on creating innovative new products and services rather than making Washington bureaucrats happy.

Additional Reading from TLF Contributors:

The FTC makes its Google investigation official, now what? – by Geoffrey Manne & Joshua Wright

What's really motivating the pursuit of Google? – by Geoffrey Manne

Search Bias and Antitrust – by Josh Wright

Sacrificing Consumer Welfare in the Search Bias Debate, Part II – by Josh Wright

The Problem of Search Engines as Essential Facilities – by Geoffrey Manne

Why Google probe should worry consumers – by Ryan Radia (in San Jose Mercury News)

Wired on Google's Coming Antitrust Nightmare – by Adam Thierer

★ Drunk on Wireless Taxes

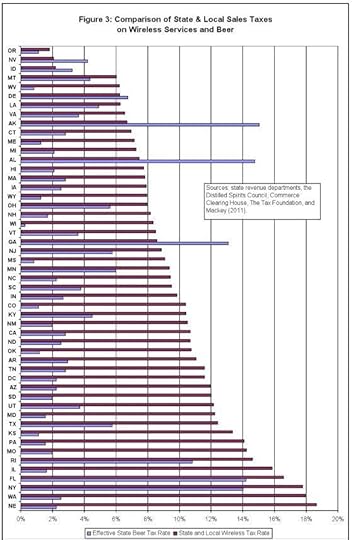

As we've noted here before, state and local politicians just love wireless taxes. They are going up, up, up. Dan Rothschild outlined this disturbing trend in his recent Mercatus Center paper making "The Case Against Taxing Cell Phone Subscribers," and I discussed it in my recent Forbes essay lambasting the "Talking Tax." Another new study by Glenn Woroch of the Georgetown University School of Business notes how "The 'Wireless Tax Premium' Harms American Consumers and Squanders the Potential of the Mobile Economy." Woroch estimates that "the American consumer forgoes over $15 billion in surplus annually compared to when cell phones receive the

As we've noted here before, state and local politicians just love wireless taxes. They are going up, up, up. Dan Rothschild outlined this disturbing trend in his recent Mercatus Center paper making "The Case Against Taxing Cell Phone Subscribers," and I discussed it in my recent Forbes essay lambasting the "Talking Tax." Another new study by Glenn Woroch of the Georgetown University School of Business notes how "The 'Wireless Tax Premium' Harms American Consumers and Squanders the Potential of the Mobile Economy." Woroch estimates that "the American consumer forgoes over $15 billion in surplus annually compared to when cell phones receive the

same tax treatment as other goods and service." Read the entire study but I want to draw everyone's attention to this chart that appears on page 7 of the report comparing state and local wireless taxes burdens to beer taxes. It really makes you realize just how drunk on wireless taxes are local lawmakers have become! [Click to enlarge. Red bar = wireless taxes.]

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower