Adam Thierer's Blog, page 108

December 13, 2011

The FCC Goes Steampunk

I've written several articles in the last few weeks critical of the dangerously unprincipled turn at the Federal Communications Commission toward a quixotic, political agenda. But as I reflect more broadly on the agency's behavior over the last few years, I find something deeper and even more disturbing is at work. The agency's unreconstructed view of communications, embedded deep in the Communications Act and codified in every one of hundreds of color changes on the spectrum map, has become dangerously anachronistic.

I've written several articles in the last few weeks critical of the dangerously unprincipled turn at the Federal Communications Commission toward a quixotic, political agenda. But as I reflect more broadly on the agency's behavior over the last few years, I find something deeper and even more disturbing is at work. The agency's unreconstructed view of communications, embedded deep in the Communications Act and codified in every one of hundreds of color changes on the spectrum map, has become dangerously anachronistic.

The FCC is required by law to see separate communications technologies delivering specific kinds of content over incompatible channels requiring distinct bands of protected spectrum. But that world ceased to exist, and it's not coming back. It is as if regulators from the Victorian Age were deciding the future of communications in the 21st century. The FCC is moving from rogue to steampunk.

With the unprecedented release of the staff's draft report on the AT&T/T-Mobile merger, a turning point seems to have been reached. I wrote on CNET (see "FCC: Ready for Reform Yet?") that the clumsy decision to release the draft report without the Commissioners having reviewed or voted on it, for a deal that had been withdrawn, was at the very least ill-timed, coming in the midst of Congressional debate on reforming the agency. Pending bills in the House and Senate, for example, are especially critical of how the agency has recently handled its reports, records, and merger reviews. And each new draft of a spectrum auction bill expresses increased concern about giving the agency "flexibility" to define conditions and terms for the auctions.

The release of the draft report, which edges the independent agency that much closer to doing the unconstitutional bidding not of Congress but the White House, won't help the agency convince anyone that it can be trusted with any new powers. Let alone the novel authority to hold voluntary incentive auctions to free up underutilized broadcast spectrum.

What is the Spectrum Screen Really Screening, Anyway?

One particularly disturbing feature of the report was what appears to be a calculated jury-rigging of the spectrum screen, as I wrote in an op-ed for The Hill. (See "FCC Plays Fast and Loose with the Law…Again") For the first time since introducing the test as a way to simplify merger review, the draft report lowers the amount of spectrum it believes available for mobile use, even as technology continues to make more spectrum usable. The lower total added 82 markets in which the screen would have been triggered, though the staff report in any case never actually performs the analysis of any local market.

The rationale for the adjustment is hidden in a non-public draft of an order on the transfer of Qualcomm's FLO-TV licenses to AT&T, an order that is only now just circulating among the Commissioners. Indeed, the Qualcomm order was only circulated a day before the T-Mobile report was released to the public and (in unredacted form) to the DoJ.

(That's the normal course of business at the agency—the T-Mobile report being the rare and disturbing exception of releasing a report before even the Commissioners have reviewed or voted on it, here in obvious hopes of influencing the Justice Department's antitrust litigation).

In the draft Qualcomm order, according to a footnote in the draft T-Mobile report, agency staff propose a first-time-ever reduction in the total amount of usable spectrum that forms the basis of the screen. (Under the test, if the total spectrum of the combined entity in a market is less than a third of the usable spectrum, the market is presumed competitive and no analysis is required.)

For purposes of the T-Mobile analysis, the unexplained reduction is assumed to be acceptable to the Commission and applied to calculations of spectrum concentration in each of the local Cellular Market Areas. (The calculation also assumes AT&T has the pending Qualcomm spectrum.) Notably, without the reduction the number of local markets in which the screen would be triggered goes down by a third.

Asked in a press conference today about the curious manipulation, FCC Chairman Genachowski refused to comment.

The spectrum screen, by the way, never made much sense. Its gross oversimplification of total usable spectrum, for one thing, hides a ridiculous assumption that all bands of usable spectrum is equally usable, defying the most basic physics of mobile communications. With a wink to the apples-and-oranges nature of different bands, since 2004 the agency has decided more or less arbitrarily to increase the total amount of "usable" spectrum by including some new bands of usable spectrum and not others, with little rhyme or reason.

The manipulation of the spectrum screen's coefficients, in fact, have no rationale other than to fast-track some preferred mergers and create regulatory headaches for others. In truth, a screen that counted all spectrum, and counted it equally, would suggest that Sprint, in combination with its subsidiary Clearwire, is the only dangerously monopolistic holder of spectrum assets. As Chart 38 of the FCC's 15th Annual Mobile Competition Report suggests, Sprint and Clearwire hold more "spectrum" than any other carrier—enough to trigger the screen in most if not all CMAs. That is, if it was all counted.

That isn't necessarily the right outcome either. Much of Clearwire's spectrum is in the >1 GHz. Bands, and, at least for now, those bands are usable but not as attractive for mobile communications as other, lower bands.

As the Mobile Competition Report notes, "these different technical characteristics provide relative advantages for the deployment of spectrum in different frequency bands under certain circumstances. For instance, there is general consensus that the more favorable propagation characteristics of lower frequency spectrum allow for better coverage across larger geographic areas and inside buildings, while higher frequency spectrum may be well suited for adding capacity."

So not all spectrum is equal after all. What, then, is the point or usefulness of the screen? And what of this unmentioned judo move in the staff report, which suddenly changed the point of the screen from one that simplified merger review to a conclusive presumption against a finding of "public interest"? The original point of the screen was to quickly eliminate competitive markets that don't require detailed analysis. In the AT&T/T-Mobile staff report, for the first time, it's used to reject a proposed transaction if too many market (how many is not indicated) are triggered that would require that analysis.

But why continue to compare apples and oranges for any purpose, when the real data on CMA competition is readily available? The only answer can be that the analysis wouldn't yield the result that the agency had in mind when it started its review. For in painstaking detail, the 15th Mobile Competition report also demonstrates that adoption is up, usage is off the charts, prices for voice, data, and text continue to plummet, investments in infrastructure continue at a dramatic pace despite the economy, and new source of competitive discipline are proliferating, in the form of device manufacturers, mobile O/S providers, app developers, and inter-modal competitors. For starters.

To conclude that AT&T's interest in T-Mobile's spectrum and physical infrastructure—an effort to overcome the failure of the FCC and local regulators to provide alternative spectrum or to allow infrastructure investments to proceed at an even faster pace—isn't in the public interest requires the staff to ignore every piece of data the same staff, in another part of the space-time contiuum, collected and published. But so long as HHIs and spectrum concentration are manipulated and relied on to foreclose real analysis, it all makes sense.

A Rogue Agency Slips into Steampunk

That is largely the point of Geoff Manne's detailed critique of the substance of the report posted here at TLF, and of my own ridiculously long post on Forbes. (See "A Strategic Plan for the FCC.")

The Forbes piece tries to put the staff report into the context of on-going calls for agency reform that were working their way through Congress even before the release. In it, I conclude that the real problem for the agency is that even with the significant changes of the 1996 Communications Act, the agency is still operating in a stovepipe model, where different communications technologies (cable, cellular, wire, satellite, "local") are still regulated separately, with different bureaus and in many cases different regulations.

The model assumes that audio and video programming are different from data communications, offered by different industries using incompatible, single-purpose technologies. A television is not a phone or a radio or a computer. Broadcast is only for programming, cellular only for voice, satellites only for industrial use. Cable is an inconveniently novel form of pay television, and data communications are only for large corporations with mainframe computers.

Those siloed regulations are further fragmented by attaching special regulatory conditions to individual license transfers and individual bands of spectrum as part of auctions. Dozens of unrelated and seemingly random requirements were added to Comcast-NBC Universal, for example. At the last minute the agency added an eccentric version of the net neutrality rules to the 2008 auction for 700 Mhz. spectrum, but only for the C block.

The agency continues to operate under an anachronistic view that distinct technologies support distinct forms of communications (radio, TV, cable, data). But the world has shifted dramatically under their feet since 1996. The convergence of nearly all networks to the Internet's single, non-proprietary standard of packet-switching, digital networks operating under TCP/IP protocols has been nothing short of a revolution in communications. But it's a revolution the agency sat out. It has no idea what role it ought to play in the post-apocalyptic world; nor has Congress given them one.

As different kinds of communications technologies have all (or nearly all) converged on IP, communications applications have blurred beyond the ability to distinguish them. Voice communications are now offered over data networks, data is flowing over the wires, TV is everywhere, and mobile devices that were unimaginable in 1996 now do everything.

Quite simply, the mismatch between the agency's structure and the reality of a single digital, virtual network treating all content as bits regardless of the technology or the source that transports it has left the agency unable to cope or to regulate rationally. Consider some of the paradoxes the agency has been forced to wrestle with in recent years:

Is Voice over IP to be regulated as a traditional voice service, with barnacled requirements for Universal Service contribution and 911 services applied and, if so, applied how?

Is TV on the Internet, delivered using any and every possible technology including wireless, fiber, copper, and cable, subject to the same Victorian standards of decency as broadcast TV, itself now entirely digital?

Is the public interest served when mobile providers combine spectrum and infrastructure assets, largely to overcome the agency's own paralysis in moving the deeply fractured spectrum map into even the 20th century and the incompetent and corrupt local zoning agencies that hold up applications for new towers and antennae until the proper tribute is rendered?

In the face of these paradoxes, the FCC has become ungrounded; a victim of its own governing statute, which in many respects requires it to remain anachronistic. Left without clear guidance from Congress on how or whether to regulate what applications (that's really all we have now—applications, independent of technology), the agency increasingly improvises.

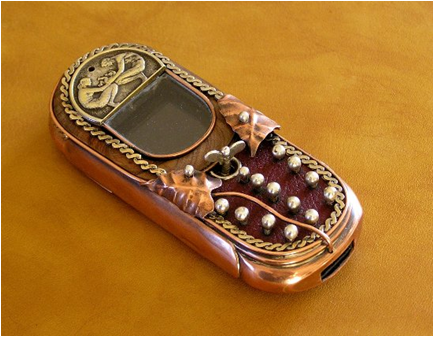

It's like the wonderful genre of animation known as "steampunk," where modern technology is projected anachronistically into the past, exploring what life would have been like if the 19th century had robots, flight, information processing, and modern armaments, all powered by the steam engine. (The concept of steam punk has now become a popular design genre, including some functioning devices wrapped in steampunk elements, as in the photo below.)

A Steampunk Computer

It's cute on film, but applied to the real world it's simply dangerous. The FCC is required by law to keep its head in the sand with respect both to the realities of digital technology and the economics of the modern communications ecosystem. Yet its natural desire to regulate something leaves the Commission flailing wildly in the dark for a foothold for its ancient regulatory structure in a world it doesn't inhabit.

The Open Internet Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, for example, asked helplessly in over 80 separate paragraphs for education and update on the nature of the revolution spurred by the deployment of broadband Internet. ("We seek more detailed comment on the technological capabilities available today, as offered for sale and as actually deployed in providers' networks.") Of course it had to ask these questions – the agency never regulated broadband. Under the 1996 Act, as the 2005 Brand X case emphasizes, it never could.

Consider just a few of the absurd counterfactuals that the agency's steampunk policies have led it in just the last few years (more examples greatly appreciated, by the way):

Broadband isn't being deployed in a "reasonable and timely fashion" (2011 Section 706 Broadband Report)

The mobile communications market is not "effectively competitive" (14th and 15th Mobile Competition Report)

High concentrations of customers and spectrum, calculated using rigged HHIs and spectrum screens, are sufficient to raise presumptive antitrust concerns regardless of actual competitive and consumer welfare (AT&T/T-Mobile draft memo)

Spectrum suitable for mobile use is decreasing (AT&T/Qualcomm memo)

Despite a lack of any examples, broadband providers "potentially face at least three types of incentives to reduce the current openness of the Internet" (Open Internet order)

Encouraging competition and protecting consumer choice "cannot be achieved by preventing only those practices that are demonstrably anticompetitive or harmful to consumers." (Open Internet order)

The agency" expect[s] the costs of compliance with our prophylactic rules to be small" (Open Internet order)

Absent a mandatory data roaming regime for mobile broadband, "there will be a significant risk that fewer consumers would have nationwide access to competitive mobile broadband services…." (Data Roaming order).

Not that there isn't considerable expertise within the agency, and glimmers of understanding that manage to escape in whiffs from the steam pipes. The 2010 National Broadband Plan, developed with a great deal of both internal and external agency expertise, does an admirable job of describing the current state of the broadband environment in the U.S. More impressive, the later chapters predict with considerable vision the application areas that will drive the next decade of broadband deployment and use, including education, employment, health care and the smart grid.

The NBP, unfortunately, is the exception. More and more of the agency's reports, orders, and decisions instead bury the expertise, forcing ridiculous conclusions through an implausible lens of nostalgia and distortion. The agency's statutorily mandated hold on a never-realistic glorious communications past is increasingly threatening the health of the real communications ecosystem–an even more glorious (largely because unregulated) communications present.

I Love it When a Plan Comes Together

The FCC's steampunk mentality is threatening to wreak havoc on the natural evolution of the Internet revolution. It's also turning the FCC from a respected and Constitutionally-required "independent" agency that answers to Congress and not the White House into a partisan monster, pursuing an agenda that's light on facts and heavy on the politics of the administration and favored participants in the Internet ecosystem. The agency relies on clichés and unexamined mantras rather than data—even its own data. Mergers are bad, edge providers are good, and the agency doesn't acknowledge that many of the genuine market failures that do exist are creatures of its own stovepipes.

As I note in the long Forbes piece, there was a simple, elegant way to avoid the steampunk phenomenon –an alternative that would have saved the FCC from increased obsolescence and the rest of us from its increasingly bizarre and disruptive regulatory behavior. And in came from within the walls of FCC headquarters.

In 1999, in the midst of the first great Web boom, then-chairman William Kennard (a Democratic appointee) had a vision for the future of communications that has proven to be entirely accurate. Kennard created a short, straightforward "strategic plan" for the agency that emphasized breaking down the silos. It also took a realistic view of the agency's need and ability to regulate an IP world, encouraging future Chairmen to get out of the way of a revolution that would provide far more benefit to consumers if left to police itself than with an FCC trying to play constant catch-up.

Kennard also proposed dramatic reform of spectrum policy, recognizing as is now obvious that imprinting the agency's stovepiped model for communications like a tattoo on the radio waves was unnecessarily limiting the uses and usefulness of mobile technology, creating artificial scarcity and, eventually, a crisis.

In just a few pages of the report, the strategic plan lays out an alternative, including flexible allocations that wouldn't require FCC permission to change uses, market-based mechanisms to ensure allocations moved easily to better and higher uses (no lingering conditions), even the creation of a spectrum inventory (still waiting). The plan called for incentive systems for spectrum reallocation, an interoperable public safety network, and expanded use of unlicensed spectrum. All reforms that we're still violently agreeing need to be made.

We've arrived, unfortunately, at precisely the future Kennard hoped to avoid. And we're still moving, at accelerating speeds, in precisely the wrong direction. Instead of working to ease spectrum restrictions and leave the "ecosystem" (the FCC's own term) to otherwise police itself, recent NPRMs and NOIs suggest an agency determined to leverage its limited broadband authority into as many aspects of the converged world as possible. As the Free State Foundation's Seth Cooper recently wrote, today's FCC has developed a "proclivity to import legacy regulations into today's IP world when doing so makes little or no sense."

Fun's fun. I like my steampunk as well as anybody. But I'd prefer to see it on a mobile broadband device, or over Netflix streamed through my IP-enabled television or game console. Or anywhere else other than at the FCC.

December 12, 2011

Face Recognition Technology Comes to Malls and Nightclubs

Over at TIME.com, I write about face detection technology and how privacy concerns around the tracking of consumers and targeted advertising online may be coming to the physical world.

As Congress and the FTC balance the public interest in privacy with the advantages of new tools, let's hope they take Sen. Rockefeller's insight to heart: Public policy does indeed have a tough time keeping up with technology. That should be a signal to policy-makers that they shouldn't be too hasty, lest they strangle a nascent technology while it's in the cradle.

Smart sign and face detection technology is very new—so new that we don't really know how consumers will react to it. It's tempting to want to get out in front privacy concerns, but it would be better to allow the technology to develop and mature a bit before we make any judgments.

Read the whole thing here.

December 9, 2011

Important Cyberlaw & Info-Tech Policy Books (2011 Edition)

It's time again to look back at the major cyberlaw and information tech policy books of the year. I've decided to drop the top 10 list approach I've used in past years (see 2008, 2009, 2010) and just use a more thematic listing of major titles released in 2011. This thematic approach gets me out of hot water since I have found that people take numeric lists very seriously, especially when they are the author of one of the books and their title isn't #1 on the list! Nonetheless, at the end, I will name what I regard as the most important Net policy book of the year.

I hope I've included all the major titles released during the year, but I ask readers to please let me know what I have missed that belongs on this list. I want this to be a useful resource to future scholars and students in the field. [Reminder: Here's my compilation of major Internet policy books from the past decade.] Where relevant, I've added links to my reviews as well as discussions with the authors that Jerry Brito conducted as part of his "Surprisingly Free" podcast series. Finally, as always, I apologize to international readers for the somewhat U.S.-centric focus of this list.

Internet Freedom / General Net Regulation & Governance

Online freedom was a major theme in the field of information technology policy in 2011, especially with the continuing hullabaloo over Wikileaks as well as the various protest movements worldwide that tapped social media and mobile technologies to organize and protest. Increased government regulation and/or crackdowns often followed. Several books dealt with these issues. Morozov's Net Delusion was one big wet blanket to the whole "Net-changes-everything" movement, but it went much too far as I noted in my lengthy review. Sifry's book was a short manifesto making the opposite case. Access Contested – the third edition in a series from the same authors — was another indispensable resource for Net researchers exploring censorship trends worldwide, with a particular focus on Asian countries in this latest edition. Finally, the Szoka & Marcus tome was an amazing collection of over 30 essays from a diverse group of scholars on a staggering array of topics. It was a great honor for me to contribute two chapters to the volume. I cannot recommend it highly enough—and it's free!

Evgeny Morozov – The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom [my review] [podcast]

Micah Sifry – WikiLeaks and the Age of Transparency [podcast]

Ronald J. Deibert, John G. Palfrey, Rafal Rohozinski and Jonathan Zittrain – Access Contested: Security, Identity, and Resistance in Asian Cyberspace

Eddan Katz & Ramesh Subramanian (Eds.) - The Global Flow of Information: Legal, Social, and Cultural Perspectives

Berin Szoka & Adam Marcus (eds.) – The Next Digital Decade: Essays on the Future of the Internet

Becky Hogge – Barefoot into Cyberspace: Adventures in Search of Techno-Utopia

Laura DeNardis – Opening Standards: The Global Politics of Interoperability

Privacy & Security

Privacy policy and government surveillance issues have been the dominant cyberlaw policy issues of 2011, so it is unsurprising that we are starting to see more major publications in this arena. Jarvis's book, in particular, generated intense debate and certainly represented one of the most important titles of the year. The Offensive Internet was a hugely important collection of essays since it represented the most forceful attack on the Net and freedom of speech to date. It was practically a jihad against Section 230 and online anonymity. I found it hugely troubling. The two primers on privacy listed below (by Solove & Schwartz and by Craig & Ludloff) were terrifically helpful, accessible booklets. I highly recommend students pick both of them up.

Saul Levmore and Martha C. Nussbaum (eds.) - The Offensive Internet: Speech, Privacy & Reputation

Jeff Jarvis – Public Parts [my review]

Daniel Solove - Nothing to Hide: The False Tradeoff between Privacy and Security [podcast]

Susan Landau - Surveillance or Security? The Risks Posed by New Wiretapping Technologies

Daniel Solove & Paul M. Schwartz – Privacy Law Fundamentals

Terence Craig and Mary Ludloff - Privacy & Big Data

Net Pessimism / Google-phobia / Copyright

Sorry for the extremely broad grouping here, but what ties these last few titles together is a general gloominess about the Internet and what it is doing to culture, learning, dialog, or particular ways of doing business. It's a common theme in Net policy book these days, as I have noted here before. I found the Pariser and Vaidhyanathan books to be extremely problematic [read my reviews]. Levine's Free Ride and Patry's How to Fix Copyright were the major online copyright policy books this year. Levine's book offered an outstanding history of the modern copyright wars, but I couldn't agree with most of his recommendations. Cleland's book was less notable for its Google-bashing than the fact it represented the beginning of an articulation of a philosophy of cyber-conservatism. Brockman's compendium of short essays on the Net's impact on us was a real hodge-podge of views, not all of which were pessimistic.

Eli Pariser – The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding From You [my review]

Siva Vaidhyanathan - The Googlization of Everything, and Why We Should Worry [my review] [podcast]

John Brockman (ed.) – Is the Internet Changing the Way You Think? The Net's Impact on Our Minds and Future

Sherry Turkle - Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other

Scott Cleland – Search & Destroy: Why You Can't Trust Google Inc. [my review]

Robert Levine – Free Ride: How the Internet is Destroying the Culture Business and How the Culture Business can Fight Back

William Patry – How to Fix Copyright

Net Policy Book of the Year

So, what was the most important info-tech policy book of 2011? I'd say it was Evgeny Morozov's Net Delusion. As I noted in previous end-of-year compendiums, I regard an "important" info-tech policy book as a title that many people are currently discussing and that we will likely be debating and referencing for many years to come. In other words, it's a book that creates a sustained buzz. Net Delusion has certainly accomplished that in major way and Morozov's relentless policy writing and Twitter ramblings kept him near the center of many Net policy debates in 2011.

That doesn't mean I agree with everything in the book, or Evgeny's style, for that matter. His Tweetstream, like many portions of his book, often drips with relentless, caustic snark-casm. I enjoy that in small doses — hell, I've used it myself on occasion here and on Twitter! — but it gets tiresome when dished out endlessly and with the volume turned up to 11. More generally, as I noted above, not only do I think he ultimately fails to prove his thesis but the book is riddled with contradictions regarding the proper disposition of governments and corporations toward the Net and online freedom. Morozov is great at tearing down the grandiose, cyber-utopian visions and visionaries, but he's far less effective at suggesting a coherent alternative vision.

Nonetheless, the importance of Morozov's work cannot be denied. He's opened a new front in the intellectual battle over the role of the Net in various political movements and causes. He aims to spearhead what we might think of as the "realist" movement that counters the more "idealist" (he would say "utopian") approach, which already has many adherents in global Net policy debates. Morozov has opened the door to more skeptical thinking in this regard. Many others are now likely to follow in his footsteps, and when they do, they will all cite back to The Net Delusion. Likewise, the idealists will now be forced to respond to Morozov in any future tracts. Thus, we'll be discussing and debating the themes in The Net Delusion for many years to come. That's why it is the most important Net policy book of 2011.

Thoughts on Cleland's "Search & Destroy" & Cyber-Conservatism

Earlier this year I read Scott Cleland's new book, Search & Destroy: Why You Can't Trust Google, Inc., after he was kind enough to send me an advance copy. I didn't have time to review it at the time and just jotted down a few notes for use later. Because the year is winding down, I figured I should get my thoughts on it out now before I publish my end of year compendium of important tech policy books.

Earlier this year I read Scott Cleland's new book, Search & Destroy: Why You Can't Trust Google, Inc., after he was kind enough to send me an advance copy. I didn't have time to review it at the time and just jotted down a few notes for use later. Because the year is winding down, I figured I should get my thoughts on it out now before I publish my end of year compendium of important tech policy books.

Cleland is President of Precursor LLC and a noted Beltway commentator on information policy issues, especially Net neutrality regulation, which he has vociferously railed against for many years. On a personal note, I've known Scott for many years and always enjoyed his analysis and wit, even when I disagree with the thrust of some of it.

And I'm sad to report that I disagree with most of it in Search & Destroy, a book that is nominally about Google but which is really a profoundly skeptical look at the modern information economy as we know it. Indeed, Cleland's book might have been more appropriately titled, "Second Thoughts about Cyberspace." In a sense, it represents an outline for an emerging "cyber-conservative" vision that aims to counter both "cyber-progressive" and "cyber-libertarian" schools of thinking.

After years of having Scott's patented bullet-point mini-manifestos land in my mailbox, I think it's only appropriate I write this review in the form of a bulleted list! So, here it goes..

The Central Irony of the Book

The central irony of the book — and one that he never confronts — is that, in the name of dealing with what he regards as "Big Brother, Inc.," Cleland thinks we must call in Big Government to deal with Google and the digital economy in general.

Cleland has spent the last decade railing against the "cyber-collectivist" or "digital commons" movement (I'll just call them "cyber-progressives") and yet, ironically, in Search & Destroy, he has adopted their tone and tactics in vilifying Google, one of the great capitalist success stories of our time.

In a sense, Cleland has unwittingly joined his cyber-conservatism with the cyber-progressivism he supposedly detests. His passionate belief in "security" and the Rule of Law quickly devolves into the Rule of Man (or regulators, that is) over a corporate entity that he fundamentally distrusts and loathes. But it also signals his acceptance of a much greater role for government in policing all of cyberspace.

On Privacy as Property & Privacy Regulation in General

The book is loaded with over-the-top rhetoric and techno-panicky talk — not just about Google but about other issues, like online privacy more generally.

Cleland has made the grave error of suggesting — again in line with the cyber-progressive movement he typically derides — that privacy should essentially be treated as property right and that extensive regulation is needed in the name of protecting privacy online.

Importantly, in railing against various types of data collection or advertising practices, Cleland doesn't seem to appreciate that his book is not just an indictment of Google but of the entire Information Economy as we know it. The data collection and online advertising practices he decries and believes should be regulated are the engines that run not just Google, but a large percentage of the business models for new and old companies alike. (I began wondering at points in the book how Cleland felt about analog era data collection companies like Experian, TransUnion, Equifax, etc.)

Indeed, there are times while reading the book when I found Cleland's views on privacy and information policy virtually indistinguishable from those of the radical Left, many of whom he cites favorably in the book! (ex: Frank Pasquale, Mark Rottenberg, GoogleWatch.)

I know Cleland will cringe at the thought, but there are clear similarities between his book and Tim Wu's book The Master Switch, with their common fears about "information empires" and "Big Brother, Inc." The difference is that Cleland singles out Google as the most problematic.

Again, this is a dangerous game Cleland is playing since his indictment of Google could be applied to many other Digital Economy operators, just as Wu has done in The Master Switch by suggesting that action needs to be taken against not just Google but also Apple, AT&T, Verizon, Facebook, Amazon, and even Twitter who are all "information monopolists" in Wu's view.

The False Link to Friedman & Hayek

Cleland is wildly off-base in enlisting the words and Milton Friedman and F.A. Hayek in support of his indictment of Google.

Cleland imagines that Google's "central planning" efforts are roughly equivalent to government central planning. That is horribly misguided and to enlist Friedman and Hayek's words in defense of this thesis is a travesty.

Friedman and Hayek's critique of central planning was squarely focused on the State, not corporations. While it may be the case that elements of their critique could be applied to large private entities that attempt audacious tasks like "organizing the all the world's information," it does not follow that the State must take action to counter those business objectives, no matter how quixotic. This is where marketplace trial and error — not anticipatory regulation — is the better way to determine what is efficient and what consumers desire.

To use a Hayekian term, Cleland is guilty of the "pretense of knowledge" problem by imagining he (or the government) has a more sensible vision for how these digital markets should look or operate. Only ongoing experimentation can tell us that.

On Solutions

We can all agree that more transparency about privacy/data collection practices (for Google and others) is generally a good idea, but it's clear that is not enough for Cleland.

He wants to bring in the wrecking ball of antitrust, thinking that this is the way to better organize the markets that Google serves.

Again, the irony is that he sees no conflict between this prescription and his general distaste for Big Government in other contexts. As I noted in my 2009 review of Gary Reback's tedious screed Free the Market, there are some conservatives who subscribe to the illogical belief that antitrust law is not a form of economic regulation. Sadly, Cleland is one of them. Instead, in his view, antitrust is about "the Rule of Law." Except that, at root, antitrust is really just as much about the Rule of Men as tradition administrative agency regulation. And those men can make many mistakes, especially when they imagine they can magically concoct a supposedly better plan for fast-moving, high-tech sectors.

Where Cyber-Conservatives & Cyber-Libertarians Part Ways

Part of what Cleland has done in this book is to further develop a theory of "cyber-conservativism."

We are beginning to see a serious schism develop between cyber-conservatives (like Scott) and cyber-libertarians (like myself and many others here at the TLF).

Over the past decade, cyber-conservatives and cyber-libertarians have been allies on many important economic policy battles (ex: Net neutrality and Net taxes are two good examples).

But the cyber-conservative desire to make everything subservient to "security and stability," and their tendency to sometimes extend property right concepts well beyond their natural or practical application, is what leads to a strong break with cyber-libertarians, who value liberty, experimentation, dynamism, and limited government above all else.

This tension is going to grow more acute in coming years as information control efforts become increasingly onerous and costly (especially on the copyright, privacy, and cyber-security fronts).

Cyber-conservatives will need to ask themselves just how far they want the State to go to achieve "security and stability," or to preserve and / or extend property rights into the sphere of intangible information flows.

Cleland's book suggests he is willing to make that leap in a fairly aggressive way to take down a company that many cyber-libertarians believe has been a great innovator and prime example of cyber-capitalism at its finest.

Like some other conservatives, Cleland has also strongly endorsed sweeping copyright regulation that would fundamentally alter the Internet's architecture in the name of protecting copyright. Most cyber-libertarians could never accept such "by-any-means-necessary" approaches to copyright protection.

But the most interesting fight in the short-term will be over privacy controls. Cleland's book signals the desire of some conservatives to have government take a more active role in the name protecting (or even "property-tizing" personal information). Some conservative policymakers, like Rep. Joe Barton (R-TX), have long been in that same boat. It will be interesting to see how many more conservatives join them and then make alliances with cyber-progressives, who are gung-ho about expanding the power of the State in this regard.

One thing is certain to me after reading Scott's book: Any alliances we cyber-libertarians make with cyber-conservatives will be fleeting and fickle affairs, just as they often are when we broker peace treaties with cyber-progressives. I suppose I was naïve to ever have thought we could bring more of either group fully into our liberty-loving camp. But what concerns me even more is that those other two camps may increasingly (sometimes unwittingly, of course) be joining forces to expand the reach of Big Government's tentacles until the entire digital economy is smothered in innovation-stifling bureaucracy and red tape.

"The natural progress of things is for liberty to yield and government to gain ground," Thomas Jefferson taught us long ago. With conservatives increasingly joining progressives in calling for greater State control of cyberspace, it is now clear to me just how lonely we libertarians will be in calling for government to keep its hands off the Net.

__________

Related Reading:

Cyber-Libertarianism: The Case for Real Internet Freedom (with Berin Szoka)

What Cablegate Tells Us about Cyber-Conservatism (by Jerry Brito)

What Privacy Conservatives & Moral Conservatives Share in Common

SOPA & Selective Memory about a Technologically Incompetent Congress

When It Comes to Information Control, Everybody Has a Pet Issue & Everyone Will Be Disappointed

And so the IP & Porn Wars Give Way to the Privacy & Cybersecurity Wars

December 8, 2011

Information Regulation that Hasn't Worked

When Senator William Proxmire (D-WI) proposed and passed the Fair Credit Reporting Act forty years ago, he almost certainly believed that the law would fix the problems he cited in introducing it. It hasn't. The bulk of the difficulties he saw in credit reporting still exist today, at least to hear consumer advocates tell it.

Advocates of sweeping privacy legislation and other regulation of the information economy would do well to heed the lessons offered by the FCRA. Top-down federal regulation isn't up to the task of designing the information society. That's the upshot of my new Cato Policy Analysis, "Reputation under Regulation: The Fair Credit Reporting Act at 40 and Lessons for the Internet Privacy Debate." In it, I compare Senator Proxmire's goals for the credit reporting industry when he introduced the FCRA in 1969 against the results of the law today. Most of the problems that existed then persist today. Some problems with credit reporting have abated and some new problems have emerged.

Credit reporting is a complicated information business. Challenges come from identity issues, judgments about biography, and the many nuances of fairness. But credit reporting is simple compared to today's expanding and shifting information environment.

"Experience with the Fair Credit Reporting Act counsels caution with respect to regulating information businesses," I write in the paper. "The federal legislators, regulators, and consumer advocates who echo Senator Proxmire's earnest desire to help do not necessarily know how to solve these problems any better than he did."

Management of the information economy should be left to the people who are together building it and using it, not to government authorities. This is not because information collection, processing, and use are free of problems, but because regulation is ill-equipped to solve them.

December 6, 2011

Michael Froomkin on the future of anonymity

On the podcast this week, Michael Froomkin, the Laurie Silvers & Mitchell Rubenstein Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Miami, discusses his new paper prepared for the Oxford Internet Institute entitled, Lessons Learned Too Well: The Evolution of Internet Regulation. Froomkin begins by talking about anonymity, why it is important, and the different political and social components involved. The discussion then turns to Froomkin's categorization of Internet regulation, how it can be seen in three different waves, and how it relates to anonymity. He ends the discussion by talking about the third wave of Internet regulation, and he predicts that online anonymity will become practically impossible. Froomkin also discusses the constitutional implications of a complete ban on online anonymity, as well as what he would deem an ideal balance between the right to anonymous speech and protection from online crimes like fraud and security breeches.

Related Links

Lessons Learned Too Well , by Froomkin"With passwords 'broken,' US rolls out Internet identity plan", ARS Technica, Technology Liberation Front

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we'd like to ask you to comment at the webpage for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

December 5, 2011

Can the spectrum crunch get any clearer?

Regardless of what you think of the AT&T/T-Mobile merger or the recently announced purchase of SpectrumCo licenses by Verizon, these deals tell us one thing: wireless carriers need access to more spectrum for mobile broadband. If they can't have access to TV broadcast spectrum, they will get it where they can, and that's by acquiring competitors.

In a new Mercatus Center Working Paper filed today as a comment in the FCC's 15th Annual Report and Analysis of Competitive Market Conditions With Respect to Mobile Wireless proceeding, Tom Hazlett writes that while the market it competitive, the prospects for "new" spectrum look dim.

[S]pectrum allocation is the essential public policy that enables—or limits—growth in mobile markets. Spectrum, assigned via liberal licenses yielding competitive operators control of frequency spaces, sets "disruptive innovation" in motion. Liberalization allowed the market to do what was unanticipated and could not be specified in a traditional FCC wireless license. That success deserves to grow; the amount of spectrum allocated to liberal licenses needs to expand. Additional bandwidth raises all consumer welfare boats, promoting competitive entry, technological upgrades, and more intense rivalry between incumbent firms.

In this, the Report (correctly) follows the strong emphasis placed on pushing bandwidth into the marketplace via liberal licenses in the FCC's National Broadband Plan, issued in March 2010. That analysis underscored the looming "mobile data tsunami," noting that the long delays associated with new spectrum allocations seriously handicap emerging wireless services. But, as if to spotlight a failure to adequately address those challenges, the FCC Report speaks approvingly of the Department of Commerce (which presides over the spectrum set-aside for federal agencies) initiative that proposes a "Fast Track Evaluation report . . . examin[ing] four spectrum bands for potential evaluation within five years . . . totaling 115 MHz . . . contingent upon the allocation of resources for necessary reallocation activities." A five-year regulatory "fast track"—if everything goes as planned.

To paraphrase John Maynard Keynes: In the long run, we're all in a dead spot.

You can read the full report at the Mercatus Center website.

More spectrum for first responders?

Over at TIME.com, I write about the recent compromise on the D Block, which would give more spectrum to public safety, and I ponder if there may not be a better way..

Patrol cars are as indispensable to police as radio communications. Yet when we provision cars to police, we don't give them steel, glass and rubber and expect them to build their own. So why do we do that with radio communications?

Read the whole thing here.

December 2, 2011

FCC Strikes Out on AT&T + T-Mobile Opportunity

AT&T and T-Mobile withdrew their merger application from the Federal Communications Commission Nov. 29 after it became clear that rigid ideologues at the FCC with no idea how to promote economic growth were determined to create as much trouble as possible.

The companies will continue to battle the U.S. Department of Justice on behalf of their deal. They can contend with the FCC later, perhaps after the next election. The conflict with DOJ will take place in a court of law, where usually there is scrupulous regard for facts, law and procedure. By comparison, the FCC is a playground for politicians, bureaucrats and lobbyists that tends to do whatever it wants.

In an unusual move, the agency released a preliminary analysis by the staff that is critical of the merger. Although the analysis has no legal significance whatsoever, publishing it is one way the zealots hope to influence the course of events given that they may no longer be in a position to judge the merger, eventually, as a result of the 2012 election.

This is not about promoting good government; this is about ideological preferences and a determination to obtain results by hook or crook.The staff analysis makes it painfully clear that the people in charge have learned very little from the failure of government to reboot the nation's economy. For starters, the analysis notes points out that "there will be fewer total direct jobs across the business," notwithstanding various commitments the companies have made to protect many existing jobs and add many new ones. The staff should have checked with the chairman of President Obama's jobs council, for one. CEO Jeff Immelt drives growth at GE through productivity and innovation, not by subsidizing inefficiency (see, e.g., this).

Immelt realizes that when government tries to preserve wasteful methods, firms become uncompetitive and lose market share. That's a recipe for unemployment. The FCC staff analysis has got it completely backwards. When politicians set out to "create" jobs, it is often at the expense of productivity. We don't need that kind of "help" from Washington. Russell Roberts recounts in a recent column a story that bears repeating here.

The story goes that Milton Friedman was once taken to see a massive government project somewhere in Asia. Thousands of workers using shovels were building a canal. Friedman was puzzled. Why weren't there any excavators or any mechanized earth-moving equipment? A government official explained that using shovels created more jobs. Friedman's response: "Then why not use spoons instead of shovels?"

FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski got it essentially correct when he remarked in a recent speech that, "Our country faces tremendous economic challenges. Millions of Americans are struggling. And new technologies and a hyper-connected, flat world mean unprecedented competition for American businesses and workers." Sadly, he does not realize that a merger between AT&T and T-Mobile provides a vehicle for that.

The combined company would have the "necessary scale, scope, resources and spectrum" to deploy fourth generation wireless services to more than 97% percent of Americans (instead of 80%), according to a filing they made in April. That would make our nation more productive and improve our competitiveness, which is we want. An analysis by Ethan Pollack at the Economic Policy Institute predicts that every $1 billion invested in wireless infrastructure will create the equivalent of approximately 12,000 jobs held for one year throughout the economy, and that if the combined company's net investment were to increase by $8 billion, the total impact would be between 55,000 and 96,000 job-years. The FCC staff thinks this is an irrelevant consideration, because it might happen anyway.

Several commenters respond that even absent the proposed transaction, AT&T would likely upgrade its full footprint to LTE in response to competition from Verizon Wireless and other mobile and other mobile wireless providers * * * * Nothing in this record suggests that AT&T is likely to depart from its historical practice of footprint-wide technological upgrades with respect to LTE even absent this transaction.

They may be right, but this is wishful thinking at a time when millions of Americans are struggling. The best course of action at this point is to improve incentives for corporations to increase capital investment, improve productivity, capture market share and create more jobs. The Feds should obviously approve this merger, because the record clearly shows that the companies are willing to undertake a massive net increase in capital investment, now.

What about the counter-argument that if there are fewer wireless providers, that may lead to consumer price increases down the road? We can worry about that later. Right now, we need to worry about the unemployed. Incidentally, increasing supply in wireless is very simple. The FCC can simply award additional spectrum for mobile communications. Almost everyone agrees that this is the best tool the government has to promote competition in wireless.

The FCC committed another unforgivable error when it tried to blow up this merger. This is not the first time the commission has recklessly put entire sectors of our nation's economy at risk while it conducts idealistic experiments for attaining consumer savings through rate regulation or regulatory mischief in pursuit perfectly competitive markets. The FCC's cable rate regulation experiment in the early 1990s and its local telephone competition experiment in the late 1990s were both total failures and complete disasters.

This agency could use some humility, or some adult supervision.

A Quick Assessment of the FCC's Appalling Staff Report on the AT&T Merger

[Cross posted at Truth on the Market]

As everyone knows by now, AT&T's proposed merger with T-Mobile has hit a bureaucratic snag at the FCC. The remarkable decision to refer the merger to the Commission's Administrative Law Judge (in an effort to derail the deal) and the public release of the FCC staff's internal, draft report are problematic and poorly considered. But far worse is the content of the report on which the decision to attempt to kill the deal was based.

With this report the FCC staff joins the exalted company of AT&T's complaining competitors (surely the least reliable judges of the desirability of the proposed merger if ever there were any) and the antitrust policy scolds and consumer "advocates" who, quite literally, have never met a merger of which they approved.

In this post I'm going to hit a few of the most glaring problems in the staff's report, and I hope to return again soon with further analysis.

As it happens, AT&T's own response to the report is actually very good and it effectively highlights many of the key problems with the staff's report. While it might make sense to take AT&T's own reply with a grain of salt, in this case the reply is, if anything, too tame. No doubt the company wants to keep in the Commission's good graces (it is the very definition of a repeat player at the agency, after all). But I am not so constrained. Using the company's reply as a jumping off point, let me discuss a few of the problems with the staff report.

First, as the blog post (written by Jim Cicconi, Senior Vice President of External & Legislative Affairs) notes,

We expected that the AT&T-T-Mobile transaction would receive careful, considered, and fair analysis. Unfortunately, the preliminary FCC Staff Analysis offers none of that. The document is so obviously one-sided that any fair-minded person reading it is left with the clear impression that it is an advocacy piece, and not a considered analysis.

In our view, the report raises questions as to whether its authors were predisposed. The report cherry-picks facts to support its views, and ignores facts that don't. Where facts were lacking, the report speculates, with no basis, and then treats its own speculations as if they were fact. This is clearly not the fair and objective analysis to which any party is entitled, and which we have every right to expect.

OK, maybe they aren't pulling punches. The fact that this reply was written with such scathing language despite AT&T's expectation to have to go right back to the FCC to get approval for this deal in some form or another itself speaks volumes about the undeniable shoddiness of the report.

Cicconi goes on to detail five areas where AT&T thinks the report went seriously awry: "Expanding LTE to 97% of the U.S. Population," "Job Gains Versus Losses," "Deutsche Telekom, T-Mobile's Parent, Has Serious Investment Constraints," "Spectrum" and "Competition." I have dealt with a few of these issues at some length elsewhere, including most notably here (noting how the FCC's own wireless competition report "supports what everyone already knows: falling prices, improved quality, dynamic competition and unflagging innovation have led to a golden age of mobile services"), and here ("It is troubling that critics–particularly those with little if any business experience–are so certain that even with no obvious source of additional spectrum suitable for LTE coming from the government any time soon, and even with exponential growth in broadband (including mobile) data use, AT&T's current spectrum holdings are sufficient to satisfy its business plans").

What is really galling about the staff report—and, frankly, the basic posture of the agency—is that its criticisms really boil down to one thing: "We believe there is another way to accomplish (something like) what AT&T wants to do here, and we'd just prefer they do it that way." This is central planning at its most repugnant. What is both assumed and what is lacking in this basic posture is beyond the pale for an allegedly independent government agency—and as Larry Downes notes in the linked article, the agency's hubris and its politics may have real, costly consequences for all of us.

Competition

But procedure must be followed, and the staff thus musters a technical defense to support its basic position, starting with the claim that the merger will result in too much concentration. Blinded by its new-found love for HHIs, the staff commits a few blunders. First, it claims that concentration levels like those in this case "trigger a presumption of harm" to competition, citing the DOJ/FTC Merger Guidelines. Alas, as even the report's own footnotes reveal, the Merger Guidelines actually say that highly concentrated markets with HHI increases of 200 or more trigger a presumption that the merger will "enhance market power." This is not, in fact, the same thing as harm to competition. Elsewhere the staff calls this—a merger that increases concentration and gives one firm an "undue" share of the market—"presumptively illegal." Perhaps the staff could use an antitrust refresher course. I'd be happy to come teach it.

Not only is there no actual evidence of consumer harm resulting from the sort of increases in concentration that might result from the merger, but the staff seems to derive its negative conclusions despite the damning fact that the data shows that wireless markets have seen considerable increases in concentration along with considerable decreases in prices, rather than harm to competition, over the last decade. While high and increasing HHIs might indicate a need for further investigation, when actual evidence refutes the connection between concentration and price, they simply lose their relevance. Someone should tell the FCC staff.

This is a different Wireless Bureau than the one that wrote so much sensible material in the 15th Annual Wireless Competition Report. That Bureau described a complex, dynamic, robust mobile "ecosystem" driven not by carrier market power and industrial structure, but by rapid evolution and technological disruptors. The analysis here wishes away every important factor that every consumer knows to be the real drivers of price and innovation in the mobile marketplace, including, among other things:

Local markets, where there are five, six, or more carriers to choose from;

Non-contract/pre-paid providers, whose strength is rapidly growing;

Technology that is making more bands of available spectrum useful for competitive offerings;

The reality that LTE will make inter-modal competition a reality; and

The reality that churn is rampant and consumer decision-making is driven today by devices, operating systems, applications and content – not networks.

The resulting analysis is stilted and stale, and describes a wireless industry that exists only in the agency's collective imagination.

There is considerably more to say about the report's tortured unilateral effects analysis, but it will have to wait for my next post. Here I want to quickly touch on a two of the other issues called out by Cicconi's blog post.

Jobs

First, although it's not really in my bailiwick to comment on the job claims that have been such an important aspect of the public conversations surrounding this merger, some things are simple logic, and the staff's contrary claims here are inscrutable. As Cicconi suggests, it is hard to understand how the $8 billion investment and build-out required to capitalize on AT&T's T-Mobile purchase will fail to produce a host of jobs, how the creation of a more-robust, faster broadband network will fail to ignite even further growth in this growing sector of the economy, and, finally, how all this can fail to happen while the FCC's own (relatively) paltry $4.5 billion broadband fund will somehow nevertheless create approximately 500,000 (!!!) jobs. Even Paul Krugman knows that private investment is better than government investment in generating stimulus – the claim is that there's not enough of it, not that it doesn't work as well. Here, however, the fiscal experts on the FCC's staff have determined that massive private funding won't create even 96,000 jobs, although the same agency claims that government funding only one half as large will create five times that many jobs. Um, really?

Meanwhile the agency simply dismisses AT&T's job preservation commitments. Now, I would also normally disregard such unenforceable pronouncements as cheap talk – except given the frequency and the volume with which AT&T has made them, they would suffer pretty mightily for failing to follow through on them now. Even more important perhaps, I have to believe (again, given the vehemence with which they have made the statements and the reality of de facto, reputational enforcement) they are willing to agree to whatever is in their control in a consent decree, thus making them, in fact, legally enforceable. For the staff to so blithely disregard AT&T's claims on jobs is unintelligible except as farce—or venality.

Spectrum

Although the report rarely misses an opportunity to fail to mention the spectrum crisis that has been at the center of the Administration's telecom agenda and the focus of the National Broadband Plan, coincidentally authored by the FCC's staff, the crux of the report seems to come down to a stark denial that such a spectrum crunch even exists. As I noted, much of the staff report amounts to an extended meditation on why the parties can and should run their businesses as the staff say they can and should. The report's section assessing the parties' claims regarding the transition to LTE (para 210, ff.) is remarkable. It begins thus:

One of the Applicants' primary justifications for the necessity of this transaction is that, as standalone firms, AT&T and T-Mobile are, and will continue to be, spectrum and capacity constrained. Due to these constraints, we find it more plausible that a spectrum constrained firm would maximize deployment of more spectrally efficient LTE, rather than limit it. Transitioning to LTE is primarily a function of only two factors: (1) the extent of LTE capable equipment deployed on the network and (2) the penetration of LTE compatible devices in the subscriber base. Although it may make it more economical, the transition does not require "spectrum headroom" as the Applicants claim. Increased deployment could be achieved by both of the Applicants on a standalone basis by adding the more spectrally efficient LTE-capable radios and equipment to the network and then providing customers with dual mode HSPAILTE devices. . . .

Forget the spectrum crunch! It is the very absence of spectrum that will give firms the incentive and the ability to transition to more-efficient technology. And all they have to do is run duplicate equipment on their networks and give all their customers new devices overnight. And, well, the whole business model fits in a few paragraphs, entails no new spectrum, actually creates spectrum, and meets all foreseeable demand (as long as demand never increases which, of course, the report conveniently fails to assess).

Moreover, claims the report, AT&T's transition to LTE flows inevitably from its competition with Verizon. But, as Cicconi points out, the staff is unprincipled in its disparate treatment of the industry's competitive conditions. Somehow, without T-Mobile in the mix, prices will skyrocket and quality will be degraded—let's say, just for example, by not upgrading to LTE (my interpretation, not the staff's). But 100 pages later, it turns out that AT&T doesn't need to merge with T-Mobile to expand its LTE network because it will have to do so in response to competition from Verizon anyway. It would appear, however, that Verizon's power over AT&T operates only if T-Mobile exists separately and AT&T has a harder time competing. Remove T-Mobile and expand AT&T's ability to compete and, apparently, the market collapses. Such is the logic of the report.

There is much more to criticize in the report, and I hope to have a chance to do so in the next few days.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower