Adam Thierer's Blog, page 106

January 8, 2012

Ezra Klein on the Importance of Advertising to Media

Washington Post columnist Ezra Klein had a terrific column yesterday (Human Knowledge, Brought to You By…) on one of my favorite subjects: how advertising is the great subsidizer of the press, media, content, and online services. Klein correctly notes that "our informational commons, or what we think of as our informational commons, is, for the most part, built atop a latticework of advertising platforms. In that way," he continues, "it's possible that no single industry — not newspapers nor search engines nor anything else — has done as much to advance the storehouse of accessible human knowledge in the 20th century as advertisers. They didn't do it because they are philanthropists, and they didn't do it because they love information. But they did it nevertheless."

Quite right. As I noted in my recent Charleston Law Review article on "Advertising, Commercial Speech & First Amendment Parity," media economists have found that advertising has traditionally provided about 70% to 80% of support for newspapers and magazines, and advertising / underwriting has entirely paid for broadcast TV and radio media. And it goes without saying that advertising has been an essential growth engine for online sites and services. How is it that we're not required to pay per search, or pay for most online news services, or shell out $19.95 a month for LinkedIn, Facebook, or other social media services? The answer, of course, is advertising. Thus, Klein notes, while "we see [] advertising as a distraction… without the advertising, the information wouldn't exist. So the history of information, in the United States at least, is the history of platforms that could support advertising."

And the sustaining power of advertising for new media continues to grow. As I noted in my law review article:

Advertising is proving increasingly to be the only media industry business model with any real staying power for many commercial media and information-producing sectors. Pay-per-view mechanisms, micropayments, and even subscription-based business models are all languishing. Consequently, the overall health of modern media marketplace and the digital economy—and the aggregate amount of information and speech that can be produced or supported by those sectors—is fundamentally tied up with the question of whether policymakers allow the advertising marketplace to evolve in an efficient, dynamic fashion. In this sense, it is not hyperbole to say that an attack on advertising is tantamount to an attack on media itself.

In this sense, I would have liked to seen Klein connect the dots between recent privacy-related legislative and regulatory proposals and the long-term health of online communities and services. As several of us here have noted here at the TLF too many times to mention, there is no free lunch. What powers the "free" Internet are data collection and advertising. In essence, the relationship between consumers and online content and service providers isn't governed by any formal contract, but rather by an unwritten quid pro quo: tolerate some ads or we'll be forced to charge you for service. Most consumers gladly take that deal—even if many of them gripe about annoying or intrusive ads, at times.

If new privacy regulations break this quid pro quo, there will be consequences. Namely, there will likely be costs in the form of prices for sites and services that relied on more targeted forms of advertising. Of course, we can hope and pray that older, more "spammy" forms of advertising (think big banner ads and pop-ups) can fill the gap and continue to sustain the online ecosystem, but it's a big gamble. Thus, I wish Klein would have pointed out that online advertising is currently under attack in both the legislative and regulatory arena and that, if new privacy mandates are put on the books, then (a) consumers should not be surprised if they have to pay more, and/or (b) we shouldn't be surprised to get less of those media and communications platforms and services in the future.

Regardless, kudos to Ezra Klein for being willing to so eloquently defend advertising's essential role as the great sustainer of media and information in America. Please do read his entire essay. Truly outstanding.

Additional Reading:

Adam Thierer, "op-ed: "Privacy Regulation and the 'Free' Internet"

Adam Thierer, Berin Szoka, and W. Kenneth Ferree, Comments of the Progress & Freedom Foundation in the Matter of the Federal Communications Commission's Examination of the Future of Media and Information Needs of Communities In a Digital Age , The Progress & Freedom Foundation, May 5, 2010, 28-38.

Adam Thierer, Public Interest Comment on Protecting Consumer Privacy in an Era of Rapid Change (Arlington, VA: Mercatus Center at George Mason University, February 18, 2011).

Berin Szoka & Adam Thierer, Online Advertising & User Privacy: Principles to Guide the Debate , Progress & Freedom Foundation, Progress Snapshot 4.19, Sept. 2008.

Berin Szoka & Adam Thierer, Targeted Online Advertising: What's the Harm & Where Are We Heading? Progress & Freedom Foundation, Progress on Point 16.2, June 2009.

Charleston Law Review Essay on Advertising and the First Amendment [PDF]

January 5, 2012

Will the Web Make NC-17 Safe For Marketing?

[Cross-posted at Reason.org]

One of the more critically praised films this year has been Shame, which has been in limited release around the country since December. Although it's an independent production, the film is being distributed by 20th Century Fox, a major studio, and stars , an actor who appears to be in the middle of his breakout moment.

The film is also rated NC-17.

Until recently, the Motion Picture Association of America's NC-17 rating, which restricts admission to theatergoers 18 and older, was the box office kiss of death. Not only did NC-17 carry the notoriety of its predecessor, the X rating, it seriously hampered a film's marketing. Boys Don't Cry, The Cooler and Clerks are among the well-known examples of acclaimed films that were cut to win the more commercially acceptable R rating, in spite of protest from their filmmakers and actors that the cuts diminished the power and the point of the scenes in question.

But most newspapers and local TV stations won't carry ads for NC-17 movies. Some theater chains, such as Cinemark, won't exhibit them. Major retailers like Wal-Mart nor video rental chains like Blockbuster won't stock NC-17-rated DVDs.

In Hollywood, art and commerce have always been in tense balance. That balance may shifting as the Web becomes a larger factor in advertising. For example, a newspaper's policy against advertising NC-17 movies is meaningless if a theater chain no longer uses newspaper advertising at all. AMC, the second biggest chain in the country, has been cutting back on print advertising since 2009. Last June, the company documented its shift from print to Web in a quarterly filing with the SEC. Regal Entertainment Group, another chain, reportedly is following suit.

Meanwhile, consumers are buying and renting fewer DVDs from brick-and-mortar outfits, choosing to buy or rent online or simply watch on demand. Netflix, for example, makes Lust, Caution, a 2007 NC-17 feature directed by Academy Award winner Ang Lee, available both by mail and streaming.

Film promotion and advertising is a great example of the way the Web has become a significant marketing vehicle. Shame, albeit a grim, downbeat story of a sex addict and his troubled sister, not only opened to favorable reviews, it had one of the most impressive box office debuts for an NC-17 movie, averaging $36,118 per screen in a tight release in ten theaters in six cities the weekend of Dec. 2-4. By comparison, that weekend's box office leader, Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn Part 1, averaged just $4,087 per screen. The Muppets, second place in total gross, averaged $3,222.

Now in wider release, Shame has made $2 million as of Jan. 3, and currently ranks eighth among the 26 NC-17 films released since 1990.

As for Web-based marketing, Shame has its own site at FoxSearchlight.com. Shame has a fan page on Facebook. "Shame" delivers several movie-related links on the first page of a Google search, pretty impressive when you consider the title is a fairly common keyword (somewhere John Bradshaw's eating his heart out).

You can find trailers for Shame at iTunes and Internet Movie Database (imdb.com), both mainstream sites for film previews. You don't have to look too hard to find the "red band" trailer, which is played in theaters only in front of R-rated movies. Studios and exhibitors also can reach audiences through sites like Yahoo and Flixster, as well as through social networking, email and Twitter. These alternatives counter the limitations of advertising policies of old media.

They also decrease the clout of the MPAA Ratings Board, which has been accused of ratings bias against smaller, independent features aimed at adult audiences. Probably the best evidence of this is presented in the documentary This Film is Not Been Rated. Well aware that an NC-17 rating can kill a film at the box office, the ratings board has not been adverse to using it as a club to tone down films which its members subjectively find either morally or tastefully questionable.

While the shortcomings of the MPAA's rating system have been discussed at length in many forums, I've always thought the most unfortunate aspect was that the MPAA never tried to counter the stigma of NC-17 as meaning "dirty movie." Unlike the Electronic Entertainment Software Association, which devised the MA AO rating for video games while successfully communicating that the market can—and should—accommodate products designed exclusively for adults, the MPAA never tried to engage the media outlets, retailers and video rental companies that openly equated NC-17 with porn.

That Web-based marketing can chip away at this perception will prove much better for audiences and filmmakers. Most NC-17 movies are not aimed at mainstream moviegoers anyway. If Shame continues to find its audience—and draws more attention in the form of several Academy Award nominations, which many critics believe it will—studios may be less inclined to make compromising cuts on the MPAA's whim out of fear of losing box office revenues. And this means a little more weight on the "art" side of art-commerce balance.

We Need More Attack Ads in Political Campaigns

A Politician Reacting to an Attack Ad

I've never understood why so many people whine about "negative attack ads" during political campaign season. To me, attack ads are just about the only interesting thing that comes out of the early campaign / caucus period. Attack ads are usually chock-full of useful information about candidates and their positions and they typically provoke or even demand a response from the politician being attacked. They also attract increased media scrutiny and broader societal deliberation about a candidate and his or her views.

More importantly, these attack ads and the responses they provoke are far, far more substantive than the typical campaign ad puffery we see and hear. Most campaign ads are packed with absurd banalities ensuring us that the candidate running the ad loves their spouse, children, country, and God. Well, of course they do! Enough of that silly crap. It's meaningless drivel. Give us more attack ads, I say! They are a healthy part of deliberative democracy and our free speech tradition.

Anyway, political scientist John G. Geer has made a far more eloquent case for attack ads and documented their use and importance throughout American history in his book, In Defense of Negativity: Attack Ads in Presidential Campaigns. Here's the link to a Cato event featuring him and an excerpt from the event is embedded below.

Vint Cerf on Why Internet Access Is Not a Human Right (+ A Few More Reasons)

In an provocative oped in today's New York Times, Vint Cerf, one of the pioneers of the Net who now holds the position "chief Internet evangelist" at Google, makes the argument for why "Internet Access Is Not a Human Right." He argues:

In an provocative oped in today's New York Times, Vint Cerf, one of the pioneers of the Net who now holds the position "chief Internet evangelist" at Google, makes the argument for why "Internet Access Is Not a Human Right." He argues:

technology is an enabler of rights, not a right itself. There is a high bar for something to be considered a human right. Loosely put, it must be among the things we as humans need in order to lead healthy, meaningful lives, like freedom from torture or freedom of conscience. It is a mistake to place any particular technology in this exalted category, since over time we will end up valuing the wrong things. For example, at one time if you didn't have a horse it was hard to make a living. But the important right in that case was the right to make a living, not the right to a horse. Today, if I were granted a right to have a horse, I'm not sure where I would put it.

The best way to characterize human rights is to identify the outcomes that we are trying to ensure. These include critical freedoms like freedom of speech and freedom of access to information — and those are not necessarily bound to any particular technology at any particular time. Indeed, even the United Nations report, which was widely hailed as declaring Internet access a human right, acknowledged that the Internet was valuable as a means to an end, not as an end in itself.

You won't be surprised to hear that I generally agree. But there are two other issues Cerf fails to address. First, who or what pays the bill for classifying the Internet or broadband as a birthright entitlement? Second, what are the potential downsides for competition and innovation from such a move? As I noted in a recent essay here ("What Does It Mean to Declare Broadband a "Human Right," and What Are the Costs?"):

We live in a world of trade-offs and there is no free lunch. One doesn't just mandate broadband for all and then expect there won't be any costs — both direct and indirect. The direct cost is the cost to taxpayers or ratepayers in form of higher taxes or bills. The indirect costs usually arrive in the form of diminished competition, limited innovation, lackluster options, and the various problems associated with the regulatory capture that will ensue.

The first objection is self-evident and needs little elaboration since we are today witnessing the breakdown of welfare state entitlement systems and policies across the globe as one country after another is bankrupted by them. But the second point needs to be unpacked a bit more.

As I noted in my earlier essay, the best universal service policy is marketplace competition. When we get the basic framework right — low taxes, property rights, contractual enforcement, anti-fraud standards, etc. — competition generally takes care of the rest. But competition often doesn't develop — or is sometimes prohibited outright — in sectors or for networks that are declared "essential" facilities or technological entitlements. That's not because they are natural monopolies, rather, it's because the policies that lawmakers and regulators put in place to ensure universal service ultimately have the counter-productive impact of retarding new entry. Worse yet, the entitlement mentality and corresponding universal service mandates typically produce less fertile ground for innovative breakthroughs. For greater ellaboration on both points, see my old 1994 essay: "Unnatural Monopoly: Critical Moments in the Development of the Bell System Monopoly."

So, while I appreciate and agree with Cerf's humorous point that "Today, if I were granted a right to have a horse, I'm not sure where I would put it," the more interesting question is this: If government would have decreed long ago that everyone had a right to a horse, would that have meant everyone actually got one? (Recall that despite a similar mandate for telephony and billions upon billions in spending / transfers, we never had more than 94% of the nation served with basic telephone service.) If everyone did actually get a horse via a hypothetical Horse Entitlement System, how efficient was that program and the resulting bureaucracy / regulatory apparatus? Who picked up the bill? Did it discourage entry by more efficient vendors? Did it discourage innovations that might have served the public better? Did the program outlive its usefulness and become a drag on innovation /productivity. Was the system gamed or captured? (I can only imagine the lobbying that would have ensued from the horse industry once trains, cars, and airplanes became a disruptive threat!)

These are the sort of questions rarely asked initially in discussions about proposals to convert technologies or networks into birthright entitlements. Eventually, however, they become inescapable problems that every entitlement system must grapple with. When we discuss the wisdom of classifying the Internet or broadband as a birthright entitlement, we should require advocates to provide us with some answers to such questions. Kudos to Vint Cerf for helping us get that conversation going in a serious way.

January 3, 2012

#FacebookFail: Diversify Your Networking

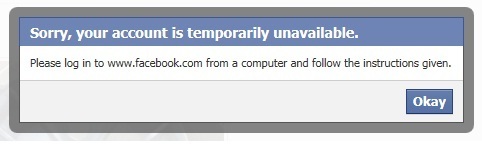

Here's the notice I've been getting the last few days when, logged into Facebook from a computer, I try to post a comment or update my status.

Clever observers will note that the recommendation to log in from a computer is misplaced, as I get it when I'm logged in from a computer. Facebook gives me no instructions when I log in (or when I log out and log in again), though it did once ask me to change my password, which I did.

Most likely, Facebook's algorithms believe I've violated some part of the Terms of Service, such as by repetitive posting or other spammy behavior. My exclusion from the site began contemporaneous with my attempt to post a single comment that failed for reasons I couldn't discern in several tries.

Undoubtedly, my friends at Facebook will leap to my aid and clear this up for me in short order, feeling slightly stung that I "went public" with the problem rather than going to them. But I wanted to experience this as an ordinary consumer, not as a member of the digerati with insider access to people at important companies. In the past, I've used insider access with services like PayPal and (the now defunct) Bitcoin7 to get help that an ordinary user couldn't have gotten. Bully for me that I can do that, but my experience is atypical and no basis for observing how the world works.

Some observations:

I've been reading a lot about data mining lately, and I have a lifelong love of mental error (not only as a practitioner!). My best guess is that the folks at Facebook have come up with an algorithmic way to recognize and exclude bad behavior (which they see in droves and endless variety). Keenly focused on excluding baddies, they've kind-of forgotten to double-check about making sure not to exclude good people. The sources of error here are many. It could be that my behavior as a user of the site produced a false positive for spamming or similar behavior. It could be that a computer of mine has a virus that is seeking to abuse my access to Facebook (though I do practice good computer hygiene). Other things might be happening that I don't know about.

But Facebook's folk haven't successfully produced a way for me to signal to them, "I am here. I'm a human, and I'm a user of your site whose behavior is ordinary and within your terms."

Thus, I can log in to Facebook, I can see what my friends are doing, and I can see what they are posting and saying about me. I just can't post any comments or update my own status. It's kind of like being locked out of your house and watching your friends have a good time inside, unable to bang on the doors or windows loud enough to get anyone's attention.

[While I think of it, would someone please post a link to this blog post on my wall? Thanks.]

It's all a little strange, but this is exactly what one can expect from a company with a customer base as large as Facebook's, enjoying continuing growth and working to add new features: imperfection.

Which brings me to my second observation: I really don't think social networks ought to scale like we're trying to make them scale. Having come to rely on one a little too much, I'm now being forced to reconsider whether I want to rely on one—and I don't. Giving the bulk of my interaction to any one platform is a risk to my ability to interact. Here, it's mistake, but any number of risks could manifest themselves, with individuals or society as a whole, if we lean too heavily on any one way of interacting.

As a basic privacy protection, for example, don't put everything you do in one place. Think of your Internet access and your social networks (and lots of other things) the way you would your stock portfolio. You're a fool of you don't diversify.

So it sure is great we have markets and competition!

I'm a Twitter user, of course. You can get an odd blend of public policy comment and quirky personal observations there at @Jim_Harper. I also have Twitter account(s) you don't get to know about.

And I'll be ramping up my use of Google+, which I did not really want to do—but, yes, I should. And I'll use it for stuff that's more work oriented. Because I'm a stickler for the meanings of words, Facebook will be for actual friends. (Meeting once is not a friendship, friends. Nor is me referring to you as part of the collective "friends" in that last sentence.)

I'll also do more on Diaspora, which is still nascent, but I think a very important network because nobody owns it. Kinda like the meatspace social network, it has no central controller, and that's a very important protection for a lot of our human and political interests—even if Diaspora is not yet hitting on all cylinders.

So there you have it! Companies are imperfect, and if you're part of the infinitesimal fraction of their customers who they fail to serve, you do get some hassles and annoyances. This counsels diversification—not only in social networks, but in all things under innovation—as a security against hassle and worse.

And finally: Ain't it cool we got options!

A Mantra for Tech Policy in the New Year

[Cross posted at TechFreedom.org]

It's hard to believe TechFreedom launched just last January. As we begin 2012, let me share with you the mantra that continues to guide our work: "Technology expands the capacity to choose; and it denies the potential of this revolution if we assume the Government is best positioned to make these choices for us."

That's how Justice Kennedy explained the Supreme Court's 2000 decision to strike down cable television censorship: better that parents choose for themselves what media are appropriate for their children. In short, as technology empowers, regulation should recede.

But except where courts impose this standard, the presumption in most tech policy debates is just the opposite: only government can protect us. In 1999, Larry Lessig predicted that "Cyberspace, left to itself, will not fulfill the promise of freedom. It will become a perfect tool of control." That pessimism shapes how most advocates, commentators, regulators, lawmakers, and even judges think about tech policy.

It's a seductive idea: If only the right policy "levers" can be pulled, in the right way, at the right time, perhaps cyberspace can come closer to fulfilling that "promise of freedom." Give me a lever large enough, some regulators seem to think, and I'll free the world!

We're skeptical—not of their motives, but of their ability to plan a free and thriving Internet. Just as Hayek said about the "curious task" of economics, we aim "to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design." Will those policy levers really do what those pulling them think? What else will they do? Will cyberspace really turn out better than if it had been left to itself?

This isn't an merely an argument for self-regulation, but for the broader, more complex process by which market forces check corporate power. For instance, when a reporter exposes a privacy violation at an Internet company, she may rightly declare that self-regulation has failed consumers. But she, too, is part of the "invisible hand" at work: She is a vital actor in the reputation "market," driving up or down the value of any Internet company's most prized asset, its reputation.

In the digital world, even the mightiest fortress of market power is built on the quicksand of a constantly changing technological landscape. Staying on top requires maintaining one's good name—and the courage to be daring. Innovation has disrupted the dominance of countless bogeymen—from Prodigy to AOL/Time Warner to Microsoft to MySpace. Each company thrived by mastering a particular paradigm—but was dethroned when that paradigm gave way to another.

If technological change would just slow down long enough, perhaps one of these companies could finally achieve "perfect control." But change won't stop—and as long as it goes on, the scramble to keep up creates a bounty of new products and services for consumers. The last thing Washington should try to do is slow things down. The very messiness and chaos of the Digital Revolution is ultimately the best guarantee that technology will indeed expand our capacity to choose for ourselves.

Government's primary role should be to ensure our choices are respected by punishing fraud and deception. Further interventions should be narrowly targeted to remedy clear harms to consumers. Education, empowerment and the enforcement of existing laws will always be the best place to start. Antitrust is generally superior to other economic regulations, but only if it serves consumers better than would the ongoing technological churn of digital paradigms. In everything it does, government must respect constitutional limits on its power to invade our privacy, censor our speech, and coerce our behavior.

This has been our message since we launched TechFreedom last January—starting with our book, The Next Digital Decade: Essays on the Future of the Internet, a unique collection of diverse scholarship available as a free download and for purchase in hardcover. Our team has since grown to include eight leading experts in Internet, communications, media and competition law and policy.

We're proud of the impact we've had. Our amicus briefs in defense of free speech over paternalistic regulations put us on the winning side of two key Supreme Court decisions: Entertainment Merchants Association v. Brown (striking down videogame censorship) and U.S. v. Sorrell (striking down censorship about health information). We've played a leading role in a number of coalition letters to Congress on policy debates ranging from copyright enforcement to protecting Americans' privacy from government snooping. These letters, and our other work, have been cited in Congressional markups by Congressmen from across the political spectrum, from Marsha Blackburn (R-TN) to Jared Polis (D-CO) and John Conyers (D-MI).

You'll see more of this kind of leadership from us in 2012 and the years beyond. Stay tuned, in particular, for a series of "Top Ten" lists looking back at 2011 and thinking forward to 2012.

Berin Szoka

President, TechFreedom

P.S. If you're not already following us on Twitter and Facebook, or by email, please do! And why not encourage your friends to do the same?

December 29, 2011

Top TLF Posts of 2011 & Year-End Analytics

As 2011 winds down, I thought I'd list a few year-end analytics for The Technology Liberation Front blog. In 2011, we had just under 400,000 visits from 332,000 unique visitors. That's up from 312,000 visits and 247,000 unique visitors in 2010.If you prefer a pageviews metric then we had 514,000 pageviews and 444,000 unique pageviews in 2011, up from 420,000 and 361,000 respectively in 2010.

As far as the top posts of the year go, anything Bitcoin related proved to be link-bait magic with 4 of the top 10 posts (all by Jerry Brito) being about Bitcoin. But it was Ryan Radia's post on how to protect your privacy on Facebook and the Net more generally that commanded the most hits in 2011 with almost 35,000 views. Congrats Ryan! Anyway, the year's Top 10 list follows below and many thanks to all those who took the time to visit the TLF over the past year.

#1) Privacy Solutions: How to Block Facebook's "Like" Button And Other Social Widgets (Ryan Radia, May 20) – 34,913 views

#2) Bitcoin, Silk Road, and Lulzsec oh my! (Jerry Brito, June 12) – 8,312 views

#3) Terrific Visualization of Digital Information Explosion (Adam Thierer, Feb 11) – 7,236 views

#4) Revisiting the Bitcoin Bubble (Jerry Brito, April 25) – 4,874 views

#5) Surveillance, San Francisco-Style (Jim Harper, April 6) – 4,555 views

#6) Bitcoin, intermediaries, and information control (Jerry Brito, April 20) – 3,362 views

#7) 3D Printing: The Future is Here (Adam Marcus, June 10) - 2,953 views

#8) Bitcoin: Imagine a net without intermediaries (Jerry Brito, April 16) – 2,750 views

#9) Book Review: The Net Delusion by Evgeny Morozov (Adam Thierer, Jan. 4) – 2,606 views

#10) A Response to Andrew McLaughlin on Net Neutrality & "Freedom" (Adam Thierer, July 9) 2,298 views

ICANN must not back down

ICANN's plan to open up the domain name space to new top level domains is scheduled to begin January 12, 2012. This long overdue implementation is the result of an open process that began in 2006. It would, in fact, be more realistic to say that the decision has been in the works 15 years; i.e., since early 1997. That is when demand for new top-level domain names, and the need for other policy decisions regarding the coordination of the domain name system, made it clear that a new institutional framework had to be created. ICANN was the progressive and innovative U.S. response to that need. It was created to become a nongovernmental, independent, truly global and representative policy development authority.

The result has been far from perfect, but human institutions never are. Over the past 15 years, every stakeholder with a serious interest in the issue of top level domains has had multiple opportunities to make their voice heard and to shape the policy. The resulting new gTLD policy reflects that diversity and complexity. From our point of view, it is too regulatory, too costly, and makes too many concessions to content regulators and trademark holders. But it will only get worse with delay. The existing compromise output that came out of the process paves the way for movement forward after a long period of artificial scarcity, opening up new business opportunities.

Now there is a cynical, illegitimate last-second push by a few corporate interests in the United States to derail that process.

The arguments put forward by these interests are not new; they are the same anti-new TLD arguments that have been made since 1997 and the concerns expressed are all addressed in one way or another by the policies ICANN has developed. Their only new claim is that they have the ear of powerful people in the United States government, including Senator Jay Rockefeller.

In effect, U.S. corporate trademark interests are openly admitting that their participation in the ICANN process has been in bad faith all along. Despite the multiple concessions and numerous re-dos that these interests managed to extract over the past 6 years, they are now demanding that everything grind to a halt because they didn't get exactly what they demanded — as if no other interests and concerns mattered and no other stakeholders exist. What they wanted, in fact, was simply to freeze the status quo of 1996 into place forever, so that there would be no new competition, no new entrepreneurial opportunities, no linguistic diversification, nothing that would have the potential to cause them any problems.

That group's demands must be rebuffed, unambiguously and finally. ICANN must start implementing the new TLD program on January 12 as scheduled. ICANN must keep its promise to those who participated in its processes in good faith.

To its everlasting credit, the U.S. Commerce Department, the official governmental contractor and supervisor of ICANN, has not caved in to the cynical corporate obstructionism. They realize what is at stake. Assistant Secretary of Commerce Lawrence Strickling is responsible and intelligent enough to understand what an unmitigated disaster it would be to pull the plug on 15 years of work.

The stakes here go well beyond the merits or de-merits of new top level domains. Any move to delay or pull back on the start date of the new TLD program is an admission that ICANN does not really make the basic policy decisions regarding the global domain name system. It is an admission that ICANN itself is a failure. That throws us straight back to 1997, re-opening all the instability and turmoil that we have tried to resolve by the creation of a new global governance institution.

If ICANN blinks, if it deviates from or delays its agreed and hard-fought policy in the slightest way, the coup d'etat succeeds. Everyone in the world then concludes that a few corporate interests in the United States hold veto power over the policies of the Internet's domain name system. Imagine the centrifugal forces that are unleashed as a result. Imagine the impact in Russia, China, Brazil, India, South Africa, and even the EU, when they are told in no uncertain terms that ICANN's policy making is hostage to the whims of a few well-placed, narrowly focused U.S. business interests; that they can invest thousands of person-hours and resources to working in that framework only to see the rug pulled out from under them by a campaign by the ANA and an editorial by the New York Times. The entire institutional infrastructure we have spent 15 years trying will be drained of its life.

Of course no one is perfectly happy with the new TLD program. But no one should assume that they can have exactly what they want, and that the whole process should be stopped until they get it. Any modification to the DNS involves millions of stakeholders and dozens of conflicting interest groups. Without question, we have reached the point where satisfying one group more, will satisfy other groups less. The idea that the basic conflicts of interest at the heart of this controversy will magically vanish if we delay things is worse than naïve, it is socially pathological. To delay now is to give one, very narrow interest group exactly what it wants (no new TLDs) and everyone else nothing. That is a far worse solution than ICANN's flawed but workable program.

On January 12, ICANN needs to make a statement that it is going forward and strongly reaffirm its ability to deliver on the promise of a nongovernmental, multistakeholder, global governance institution. It should celebrate the opening of its application. It should throw a big party. In this case, it has both the authority and the legitimacy it needs to proceed.

December 28, 2011

On Nostalgia

Just last week I was discussing the terrifically interesting work of Michael Sacasas who pens The Frailest Thing, a poetic blog about technology and culture. [see: "Information Revolutions & Cultural / Economic Tradeoffs"] I highly recommend you follow his blog even if you struggle to keep up with his brilliance, as I often do. He posted another great essay today entitled, "Nostalgia: The Third Wave," in which he discusses the work of the late social critic Christopher Lasch and his work on memory and nostalgia. Go read the entire thing since I cannot possible do it justice here. Anyway, I posted a short comment over there that I thought I would just republish here in case others are interested. I find the issue of nostalgia to be quite interesting.

_______

Michael… I'm currently finishing up a paper looking at the causes of various "techno-panics" over time. I try to group together a variety of theories and possible explanations, one of which is labeled "Hyper-Nostalgia, Pessimistic Bias & Soft Ludditism." I don't go into anywhere near the detail you do here, but I did unearth a number of interesting things while conducting research.

Have you ever come across the book On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection, by the poet Susan Stewart? She notes that what is ironic about nostalgia is that it is rooted in something typically unknown by the proponent. Consequently, she argues that nostalgia represents "a sadness without an object, a sadness which creates a longing that of necessity is inauthentic because it does not take part in lived experience. Rather, it remains behind and before that experience." Too often, Stewart observes, "nostalgia wears a distinctly utopian face" and thus becomes a "social disease."

That's probably a bit extreme, but it does help explain why some intellectuals, social critics, and policymakers occasionally demonize new mediums, technologies, or forms of culture. If one if suffering from a rather extreme version of what Michael Shermer refers to this as "rosy retrospection bias," (The Believing Brain, 2011) or "the tendency to remember past events as being more positive than they actually were," then it would hardly be surprising that they would adopt attitudes and policies that disfavor the new and different.

Indeed, many critics fear how technological evolution challenges the old order, traditional values, settled norms, traditional business models, and existing institutions. Stated differently, by its nature, technology disrupts settled matters and, therefore, "the shock of the new often brings out critics eager to warn us away," notes Dennis Baron, author of A Better Pencil. Occasionally, this marriage of distaste for the new and a longing for the past (often referred to as a "simpler time" or "the good old days") yields the sort of a moral panics or technopanics I discuss in my paper. In particular, cultural critics and advocacy groups benefit from the use of nostalgia by playing into, or whipping up, fears that there was a better time we've lost and then suggesting "steps should be taken" to help us return to that time.

I regard that as dangerous because it implies someone knows how to set society back on that supposedly better course even though they haven't likely taken into account the full costs of even attempting to do so. Those costs could be speech-related (censorship), social (unnecessary changes in how we educate children) or economic (disruption of new technologies or business methods). That would be the downside of hyper-nostalgia if given the effect of law.

I guess it all comes back to what the Scottish philosopher and economist David Hume observed in a 1777 essay: "The humour of blaming the present, and admiring the past, is strongly rooted in human nature, and has an influence even on persons endued with the profoundest judgment and extensive learning." The problem is, when we act on those well-ingrained instincts, it has consequences and those consequences could be profound. Thus, I would argue we should establish a fairly high bar when it comes to nostalgic assertions about "a better time" to which some would have us return. Because in my eyes, those "good 'ol days" — whenever those were — were rarely as great as some claim.

Of course, others might claim that I am, once again, just being too much of a Pollyanna!

December 23, 2011

Information Revolutions & Cultural / Economic Tradeoffs

My thanks to both Maria H. Andersen and Michael Sacasas for their thoughtful responses to my recent Forbes essay on "10 Things Our Kids Will Never Worry About Thanks to the Information Revolution." They both go point by point through my Top 10 list and offer an alternative way of looking at each of the trends I identify. What their responses share in common is a general unease with the hyper-optimism of my Forbes piece. That's understandable. Typically in my work on technological "optimism" and "pessimism" — and yes, I admit those labels are overly simplistic — I always try to strike a sensible balance between pollyannism and hyper-pessimism as it pertains to the impact of technological change on our culture and economy. I have called this middle ground position "pragmatic optimism." In my Forbes essay, however, I was in full-blown pollyanna mode. That doesn't mean I don't generally feel very positive about the changes I itemized in that essay, rather, I just didn't have the space in a 1,000-word column to identify the tradeoffs inherent in each trend. Thus, Andersen and Sacasas are rightfully pushing back against my lack of balance.

But there is a problem with their slightly pessimistic pushback, too. To better explain my own position and respond to Andersen and Sacasas, let me return to the story we hear again and again in discussion about technological change: the well-known allegorical tale from Plato's Phaedrus about the dangers of the written word. In the tale, the god Theuth comes to King Thamus and boasts of how Theuth's invention of writing would improve the wisdom and memory of the masses relative to the oral tradition of learning. King Thamus shot back, "the discoverer of an art is not the best judge of the good or harm which will accrue to those who practice it." King Thamus then passed judgment himself about the impact of writing on society, saying he feared that the people "will receive a quantity of information without proper instruction, and in consequence be thought very knowledgeable when they are for the most part quite ignorant."

After recounting Plato's allegory in my essay, "Are You An Internet Optimist or Pessimist? The Great Debate over Technology's Impact on Society," I noted how this same tension has played out in every subsequent debate about the impact of a new technology on culture, values, morals, language, learning, and so on. It is a never-ending cycle. Now, here's the interesting thing about that allegory that you will be surprised to hear an optimist like me admit: King Thamus was right! Well, at least partially right. There is little doubt that the invention of writing largely displaced the tradition of oral learning and instruction. Let's face it, once people knew they could write something down or go back and read a passage from an important text, what was the use in memorizing it? Thus, there was a clear cost associated with the advent of writing and printing: A diminished interest in committing lessons or texts to memory. More profoundly, one might argue this also diminished our cognitive capabilities by requiring less of a mental workout for our brains. Thus, had Nick Carr been around to document the Theuth-Thamus debate, he might have penned a book entitled, "Is Writing Making Us Stupid?" (I'm assuming everyone is aware of Nick's recent article asking "Is Google Making Us Stupid" and his subsequent book, The Shallows, which discussed "what the Internet is doing to our brains.") Of course, it would have been a bit ironic for Nick to write it all down, so perhaps he would have just memorized it all and verbally passed his analysis along to descendants and followers!

Anyway, here's what I am getting at by returning to Plato's allegory: Technological change forces tradeoffs upon us. It forces sacrifices. There are definitely losses. But, in each case, we must ask two essential questions:

(1) Don't the benefits of technological change generally outweigh the costs? I think they generally do, and that's why I tend to side with the optimists more often than not. Sure, we can find plenty of reasons to be nostalgic about the decline of letter-writing, the disappearance of expensive encyclopedias, the end of typing classes, the elimination of phone booths on the corner, the loss of community video stores or record stores, or any of the other things I identified in my Forbes essay. But we should consider the many ways in which those changes have generally benefited society and opened the door to new innovations, new ways of learning and communicating, and new forms of culture and expression.

(2) Even if we are skeptical about the benefits of technological change, what are we going to do about it? Are we going to take steps to slow down technological change? What sort of steps are we talking about? Who makes that call or determines those responses? These are difficult but essential questions. Too many social critics get a free pass when it comes to answering them. This is what always drives me batty when reading the work of Net pessimists like Neil Postman, Lee Siegel, Andrew Keen, Jaron Lanier, etc. These guys excel at the art of the teardown. They can lambast the agents and elements of technological change with immense rhetorical power. At times, even I find their case convincing. But these critics are horrible when it comes to proposing alternatives or constrictive solutions. Often they have none. I believe it is the duty of a good social critic to offer constrictive solutions to the problems they identify. One reason they probably don't offer many is because they are simply afraid to admit that, if they could play God for a day, they probably would roll back the clock and slow or stop many forms of technological change.

The more constructive approach to these challenges comes back to education and empowerment. If we can be mature enough to (a) admit that pessimistic social critics have some valid concerns but that (b) the optimists are right about the benefits typically outweighing the costs, then the logical response is to take steps to educate people about technological change and empower them to deal with it. Other times, however, people simply have to learn how to adapt and be resilient through experimentation and coping strategies. It isn't easy, of course. But education can help here, too. I've spent time trying to educate my father and other older relatives about how to use digital technologies they continue to be very uncomfortable with. I appreciate their concerns about privacy, security, and technological complexity. These are valid concerns or complaints. But these technologies are not going away and I have taken upon myself to help them assimilate the new tools and methods into their lives. I also mentor my children and guide their use of these new information technologies. They are surprisingly good at adapting to their new tools, but we must take to heart the lessons the social critics and pessimists offer about the downsides and dangers of some of those new tools.

As you can sense, my perspective here is very much shaped by the fact that I am, for the most part, a technological determinist. Not a rigid or "hard" tech determinist, but at least a "soft" one. In a brilliant and highly provocative recently paper, "Hasta La Vista Privacy, or How Technology Terminated Privacy," Konstantinos K. Stylianou of the University of Pennsylvania Law School discusses varieties of technological determinism as it pertains to information control and noted:

In-between the two extremes (technology as the defining factor of change and technology as a mere tangent of change) and in a multitude of combinations falls the so called soft determinism; that is, variations of the combined effect of technology on one hand and human choices and actions on the other. (p. 46)

Unfortunately, Stylianou notes, "The scope of soft determinism is unfortunately so broad that is loses all normative value. Encapsulated in the axiom 'human beings do make their world, but they are also made by it,' soft determinism is reduced to the self-evident." Nonetheless, he argues, "a compromise can be reached by mixing soft and hard determinism in a blend that reserves for technology the predominant role only in limited cases," since he believes "there are indeed technologies so disruptive by their very nature they cause a certain change regardless of other factors." (p. 46) He concludes his essay by noting:

it seems reasonable to infer that the thrust behind technological progress is so powerful that it is almost impossible for traditional legislation to catch up. While designing flexible rules may be of help, it also appears that technology has already advanced to the degree that is is able to bypass or manipulate legislation. As a result, the cat-and-mouse chase game between the law and technology will probably always tip in favor of technology. It may thus be a wise choice for the law to stop underestimating the dynamics of technology, and instead adapt to embrace it. (p. 54)

That pretty much sums up where I'm at on most information policy issues and explains why I sound so fatalistic at times. But my soft determinism also explains why I feel it is so important to devise coping strategies to help us through the changes that the information revolution has ushered in and forced upon us. There's just no putting the digital genie back in the bottle. We can wax nostalgic all we want about those supposedly "good 'ol days" but they ain't never coming back. And they weren't that great anyway!

If this discussion interests you, you might want to read my book chapter from the book The Next Digital Decade, which was entitled, "The Case for Internet Optimism, Part 1: Saving the Net From Its Detractors." Oh, and if you don't already have Michael Sacasas's blog (The Frailest Thing) at the top of your RSS feed, add it now. Absolutely terrific reading, even when I don't agree with (or even understand!) all of it.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower