Nicole Yunger Halpern's Blog

November 26, 2025

What distinguishes quantum from classical thermodynamics?

Should you require a model for an Oxford don in a play or novel, look no farther than Andrew Briggs. The emeritus professor of nanomaterials speaks with a southern-English accent as crisp as shortbread, exhibits manners to which etiquette influencer William Hanson could aspire, and can discourse about anything from Bantu to biblical Hebrew. I joined Andrew for lunch at St. Anne’s College, Oxford, this month.1 Over vegetable frittata, he asked me what unifying principle distinguishes quantum from classical thermodynamics.

With a thermodynamic colleague at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History

With a thermodynamic colleague at the Oxford University Museum of Natural HistoryI’d approached quantum thermodynamics from nearly every angle I could think of. I’d marched through the thickets of derivations and plots; I’d journeyed from subfield to subfield; I’d gazed down upon the discipline as upon a landscape from a hot-air balloon. I’d even prepared a list of thermodynamic tasks enhanced by quantum phenomena: we can charge certain batteries at greater powers if we entangle them than if we don’t, entanglement can raise the amount of heat pumped out of a system by a refrigerator, etc. But Andrew’s question flummoxed me.

I bungled the answer. I toted out the aforementioned list, but it contained examples, not a unifying principle. The next day, I was sitting in an office borrowed from experimentalist Natalia Ares in New College, a Gothic confection founded during the late 1300s (as one should expect of a British college called “New”). Admiring the view of ancient stone walls, I realized how I should have responded the previous day.

View from a window near the office I borrowed in New College. If I could pack that office in a suitcase and carry it home, I would.

View from a window near the office I borrowed in New College. If I could pack that office in a suitcase and carry it home, I would.My answer begins with a blog post written in response to a quantum-thermodynamics question from a don at another venerable university: Yoram Alhassid. He asked, “What distinguishes quantum thermodynamics to quantum statistical mechanics?” You can read the full response here. Takeaways include thermodynamics’s operational flavor. When using an operational theory, we imagine agents who perform tasks, using given resources. For example, a thermodynamic agent may power a steamboat, given a hot gas and a cold gas. We calculate how effectively the agents can perform those tasks. For example, we compute heat engines’ efficiencies. If a thermodynamic agent can access quantum resources, I’ll call them “quantum thermodynamic.” If the agent can access only everyday resources, I’ll call them “classical thermodynamic.”

A quantum thermodynamic agent may access more resources than a classical thermodynamic agent can. The latter can leverage work (well-organized energy), free energy (the capacity to perform work), information, and more. A quantum agent may access not only those resources, but also entanglement (strong correlations between quantum particles), coherence (wavelike properties of quantum systems), squeezing (the ability to toy with quantum uncertainty as quantified by Heisenberg and others), and more. The quantum-thermodynamic agent may apply these resources as described in the list I rattled off at Andrew.

With Oxford experimentalist Natalia Ares in her lab

With Oxford experimentalist Natalia Ares in her labYet quantum phenomena can impede a quantum agent in certain scenarios, despite assisting the agent in others. For example, coherence can reduce a quantum engine’s power. So can noncommutation. Everyday numbers commute under multiplication: 11 times 12 equals 12 times 11. Yet quantum physics features numbers that don’t commute so. This noncommutation underlies quantum uncertainty, quantum error correction, and much quantum thermodynamics blogged about ad nauseam on Quantum Frontiers. A quantum engine’s dynamics may involve noncommutation (technically, the Hamiltonian may contain terms that fail to commute with each other). This noncommutation—a fairly quantum phenomenon—can impede the engine similarly to friction. Furthermore, some quantum thermodynamic agents must fight decoherence, the leaking of quantum information from a quantum system into its environment. Decoherence needn’t worry any classical thermodynamic agent.

In short, quantum thermodynamic agents can benefit from more resources than classical thermodynamic agents can, but the quantum agents also face more threats. This principle might not encapsulate how all of quantum thermodynamics differs from its classical counterpart, but I think the principle summarizes much of the distinction. And at least I can posit such a principle. I didn’t have enough experience when I first authored a blog post about Oxford, in 2013. People say that Oxford never changes, but this quantum thermodynamic agent does.

In the University of Oxford Natural History Museum in 2013, 2017, and 2025. I’ve published nearly 150 Quantum Frontiers posts since taking the first photo!

1Oxford consists of colleges similarly to how neighborhoods form a suburb. Residents of multiple neighborhoods may work in the same dental office. Analogously, faculty from multiple colleges may work, and undergraduates from multiple colleges may major, in the same department.

October 26, 2025

The sequel

This October, fantasy readers are devouring a sequel: the final installment in Philip Pullman’s trilogy The Book of Dust. The series follows student Lyra Silvertongue as she journeys from Oxford to the far east. Her story features alternate worlds, souls that materialize as talking animals, and a whiff of steampunk. We first met Lyra in the His Dark Materials trilogy, which Pullman began publishing in 1995. So some readers have been awaiting the final Book of Dust volume for 30 years.

Another sequel debuts this fall. It won’t spur tens of thousands of sales; nor will Michael Sheen narrate an audiobook version of it. Nevertheless, the sequel should provoke as much thought as Pullman’s: the sequel to the Maryland Quantum-Thermodynamics Hub’s first three years.

More deserving of a Carnegie Medal than our hub, but the hub deserves no less enthusiasm!

More deserving of a Carnegie Medal than our hub, but the hub deserves no less enthusiasm!The Maryland Quantum-Thermodynamics Hub debuted in 2022, courtesy of a grant from the John F. Templeton Foundation. Six theorists, three based in Maryland, have formed the hub’s core. Our mission has included three prongs: research, community building, and outreach. During the preceding decade, quantum thermodynamics had exploded, but mostly outside North America. We aimed to provide a lodestone for the continent’s quantum-thermodynamics researchers and visitors.

Also, we aimed to identify the thermodynamics of how everyday, classical physics emerges from quantum physics. Quantum physics is reversible (doesn’t distinguish the past from the future), is delicate (measuring a quantum system can disturb it), and features counterintuitive phenomena such as entanglement. In contrast, our everyday experiences include irreversibility (time has an arrow), objectivity (if you and I read this article, we should agree about its contents), and no entanglement. How does quantum physics give rise to classical physics at large energy and length scales? Thermodynamics has traditionally described macroscopic, emergent properties. So quantum thermodynamics should inform our understanding of classical reality’s emergence from quantum mechanics.

Our team has approached this opportunity from three perspectives. One perspective centers on quantum Darwinism, a framework for quantifying how interactions spread information about an observed quantum system. Another perspective highlights decoherence, the contamination of a quantum system by its environment. The third perspective features incompatible exchanged quantities, described in an earlier blog post. Or two. Or at least seven.

Each perspective led us to discover a tension, or apparent contradiction, that needs resolving. One might complain that we failed to clinch a quantum-thermodynamic theory of the emergence of classical reality. But physicists adore apparent contradictions as publishers love splashing “New York Times bestseller” on their book covers. So we aim to resolve the tensions over the next three years.

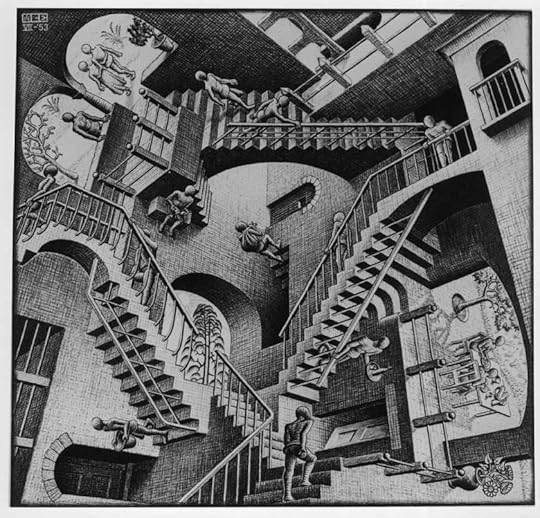

Physicists savor paradoxes and their ilk.

Physicists savor paradoxes and their ilk.I’ll illustrate the tensions with incompatible exchanged quantities, of course. Physicists often imagine a small system, such as a quantum computer, interacting with a large environment, such as the surrounding air and the table on which the quantum computer sits. The system and environment may exchange energy, particles, electric charge, etc. Typically, the small system thermalizes, or reaches a state mostly independent of its initial conditions. For example, after exchanging enough energy with its environment, the system ends up at the environment’s temperature, mostly regardless of the system’s initial temperature.

For decades, physicists implicitly assumed that the exchanged quantities are compatible: one can measure them simultaneously. But one can’t measure all of a quantum system’s properties simultaneously. Position and momentum form the most famous examples. Incompatibility epitomizes quantum physics, underlying Heisenberg’s uncertainty relation, quantum error correction, and more. So collaborators and I ask how exchanged quantities’ incompatibility alters thermalization, which helps account for time’s arrow.

Our community has discovered that such incompatibility can hinder certain facets of thermalization—in a sense, stave off certain aspects of certain quantum systems’ experience of time. But incompatible exchanged quantities enhance other features of thermalization. How shall we reconcile the hindrances with the enhancements? Does one of the two effects win out? I hope to report back in three years. For now, I’m rooting for Team Hindrance.

In addition to resolving apparent conflicts, we’re adding a fourth perspective to our quiver—a gravitational one. In our everyday experiences, space-time appears smooth; unlike Lyra’s companion Will in The Subtle Knife, we don’t find windows onto other worlds. But quantum physics, combined with general relativity, suggests that you’d find spikes and dips upon probing space-time over extremely short length scales. How does smooth space-time emerge from its quantum underpinnings? Again, quantum thermodynamics should help us understand.

To address these challenges, we’re expanding the hub’s cast of characters. The initial cast included six theorists. Two more are joining the crew, together with the hub’s first two experimentalists. So is our first creative-writing instructor, who works at the University of Maryland (UMD) Jiménez-Porter Writers’ House.

As the hub has grown, so has the continent’s quantum-thermodynamics community. We aim to continue expanding that community and strengthening its ties to counterparts abroad. As Lyra learned in Pullman’s previous novel, partnering with Welsh miners and Czech book sellers and Smyrnan princesses can further one’s quest. I don’t expect the Maryland Quantum-Thermodynamics Hub to attract Smyrnan princesses, but a girl can dream. The hub is already partnering with the John F. Templeton Foundation, Normal Computing, the Fidelity Center for Applied Technology, the National Quantum Laboratory, Maryland’s Capital of Quantum team, and more. We aim to integrate quantum thermodynamics into North America’s scientific infrastructure, so that the field thrives here even after our new grant terminates. Reach out if you’d like to partner with us.

To unite our community, the hub will host a gathering—a symposium or conference—each year. One conference will feature quantum thermodynamics and quantum-steampunk creative writing. Scientists and authors will present. We hope that both groups will inspire each other, as physicist David Deutsch’s work on the many-worlds formulation of quantum theory inspired Pullman.

That conference will follow a quantum-steampunk creative-writing course to take place at UMD during spring 2026. I’ll co-teach the course with creative-writing instructor Edward Daschle. Students will study quantum thermodynamics, read published science-fiction stories, write quantum-steampunk stories, and critique each other’s writing. Five departments have cross-listed the course: physics, arts and humanities, computer science, chemistry, and mechanical engineering. If you’re a UMD student, you can sign up in a few weeks. Do so early; seats are limited! We welcome graduate students and undergrads, the latter of whom can earn a GSSP general-education credit.1 Through the course, the hub will spread quantum thermodynamics into Pullman’s world—into literature.

Pullman has entitled his latest novel The Rose Field. The final word refers to an object studied by physicists. A field, such as an electric or gravitational field, is a physical influence spread across space. Hence fiction is mirroring physics—and physics can take its cue from literature. As ardently as Lyra pursues the mysterious particle called Dust, the Maryland Quantum-Thermodynamics Hub is pursuing a thermodynamic understanding of the classical world’s emergence from quantum physics. And I think our mission sounds as enthralling as Lyra’s. So keep an eye on the hub for physics, community activities, and stories. The telling of Lyra’s tale may end this month, but the telling of the hub’s doesn’t.

1Just don’t ask me what GSSP stands for.

September 21, 2025

Blending science with fiction in Baltimore

I judge a bookstore by the number of Diana Wynne Jones novels it stocks. The late British author wrote some of the twentieth century’s most widely lauded science-fiction and fantasy (SFF). She clinched more honors than I should list, including two World Fantasy Awards. Neil Gaiman, author of American Gods, called her “the best children’s writer of the last forty years” in 2010—and her books suit children of all ages.1 But Wynne Jones passed away as I was finishing college, and her books have been disappearing from American bookshops. The typical shop stocks, at best, a book in the series she began with Howl’s Moving Castle, which Hayao Miyazaki adapted into an animated film.

I don’t recall the last time I glimpsed Deep Secret in a bookshop, but it ranks amongst my favorite Wynne Jones books—and favorite books, full-stop. So I relished living part of that book this spring.

Deep Secret centers on video-game programmer Rupert Venables. Outside of his day job, he works as a Magid, a magic user who helps secure peace and progress across the multiple worlds. Another Magid has passed away, and Rupert must find a replacement for him. How does Rupert track down and interview his candidates? By consolidating their fate lines so that the candidates converge on an SFF convention. Of course.

My fate line drew me to an SFF convention this May. Balticon takes place annually in Baltimore, Maryland. It features not only authors, agents, and publishers, but also science lecturers. I received an invitation to lecture about quantum steampunk—not video-game content,2 but technology-oriented like Rupert’s work. I’d never attended an SFF convention,3 so I reread Deep Secret as though studying for an exam.

Rupert, too, is attending his first SFF convention. A man as starched as his name sounds, Rupert packs suits, slacks, and a polo-neck sweater for the weekend—to the horror of a denim-wearing participant. I didn’t bring suits, in my defense. But I did dress business-casual, despite having anticipated that jeans, T-shirts, and capes would surround me.

I checked into a Renaissance Hotel for Memorial Day weekend, just as Rupert checks into the Hotel Babylon for Easter weekend. Like him, I had to walk an inordinately long distance from the elevators to my room. But Rupert owes his trek to whoever’s disrupted the magical node centered on his hotel. My hotel’s architects simply should have installed more elevator banks.

Balticon shared much of its anatomy with Rupert’s con, despite taking place in a different century and country (not to mention world). Participants congregated downstairs at breakfast (continental at Balticon, waitered at Rupert’s hotel). Lectures and panels filled most of each day. A masquerade took place one night. (I slept through Balticon’s; impromptu veterinary surgery occupies Rupert during his con’s.) Participants vied for artwork at an auction. Booksellers and craftspeople hawked their wares in a dealer’s room. (None of Balticon’s craftspeople knew their otherworldly subject matter as intimately as Rupert’s Magid colleague Zinka Fearon does, I trust. Zinka paints her off-world experiences when in need of cash.)

In our hotel room, I read out bits of Deep Secret to my husband, who confirmed the uncanniness with which they echoed our experiences. Both cons featured floor-length robes, Batman costumes, and the occasional slinky dress. Some men sported long-enough locks, and some enough facial hair, to do a Merovingian king proud. Rupert registers “a towering papier-mâché and plastic alien” one night; on Sunday morning, a colossal blow-up unicorn startled my husband and me. We were riding the elevator downstairs to breakfast, pausing at floor after floor. Hotel guests packed the elevator like Star Wars fans at a Lucasfilm debut. Then, the elevator halted again. The doors opened on a bespectacled man, 40-something years old by my estimate, dressed as a blue-and-white unicorn. The costume billowed out around him; the golden horn towered multiple feet above his head. He gazed at our sardine can, and we gazed at him, without speaking. The elevator doors shut, and we continued toward breakfast.

Photo credit: Balticon

Photo credit: BalticonDespite having read Deep Secret multiple times, I savored it again. I even laughed out loud. Wynne Jones paints the SFF community with the humor, exasperation, and affection one might expect of a middle-school teacher contemplating her students. I empathize, belonging to a community—the physics world—nearly as idiosyncratic as the SFF community.4 Wynne Jones’s warmth for her people suffuses Deep Secret; introvert Rupert surprises himself by enjoying a dinner with con-goers and wishing to spend more time with them. The con-goers at my talk exhibited as much warmth as any audience I’ve spoken to, laughing, applauding, and asking questions. I appreciated sojourning in their community for a weekend.5

This year, my community is fêting the physicists who founded quantum theory a century ago. Wynne Jones sparked imaginations two decades ago. Let’s not let her memory slip from our fingertips like a paperback over which we’re falling asleep. After all, we aren’t forgetting Louis de Broglie, Paul Dirac, and their colleagues. So check out a Wynne Jones novel the next time you visit a library, or order a novel of hers to your neighborhood bookstore. Deep Secret shouldn’t be an actual secret.

With thanks to Balticon’s organizers, especially Miriam Winder Kelly, for inviting me and for fussing over their speakers’ comfort like hens over chicks.

1Wynne Jones dedicated her novel Hexwood to Gaiman, who expressed his delight in a poem. I fancy the comparison of Gaiman, a master of phantasmagoria and darkness, to a kitten.

2Yet?

3I’d attended a steampunk convention, and spoken at a Boston SFF convention, virtually. But as far as such conventions go, attending virtually is to attending in person as my drawings are to a Hayao Miyazaki film.

4But sporting fewer wizard hats.

5And I wonder what the Diana Wynne Jones Conference–Festival is like.

September 18, 2025

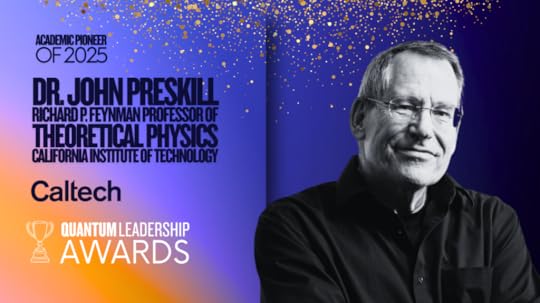

John Preskill receives 2025 Quantum Leadership Award

The 2025 Quantum Leadership Awards were announced at the Quantum World Congress on 18 September 2025. Upon receiving the , John Preskill made these remarks.

I’m enormously excited and honored to receive this Quantum Leadership Award, and especially thrilled to receive it during this, the International Year of Quantum. The 100th anniversary of the discovery of quantum mechanics is a cause for celebration because that theory provides our deepest and most accurate description of how the universe works, and because that deeper understanding has incalculable value to humanity. What we have learned about electrons, photons, atoms, and molecules in the past century has already transformed our lives in many ways, but what lies ahead, as we learn to build and precisely control more and more complex quantum systems, will be even more astonishing.

As a professor at a great university, I have been lucky in many ways. Lucky to have the freedom to pursue the scientific challenges that I find most compelling and promising. Lucky to be surrounded by remarkable, supportive colleagues. Lucky to have had many collaborators who enabled me to do things I could never have done on my own. And lucky to have the opportunity to teach and mentor young scientists who have a passion for advancing the frontiers of science. What I’m most proud of is the quantum community we’ve built at Caltech, and the many dozens of young people who imbibed the interdisciplinary spirit of Caltech and then moved onward to become leaders in quantum science at universities, labs, and companies all over the world.

Right now is a thrilling time for quantum science and technology, a time of rapid progress, but these are still the early days in a nascent second quantum revolution. In quantum computing, we face two fundamental questions: How can we scale up to quantum machines that can solve very hard computational problems? And once we do so, what will be the most important applications for science and for industry? We don’t have fully satisfying answers yet to either question and we won’t find the answers all at once – they will unfold gradually as our knowledge and technology advance. But 10 years from now we’ll have much better answers than we have today.

Companies are now pursuing ambitious plans to build the world’s most powerful quantum computers. Let’s not forget how we got to this point. It was by allowing some of the world’s most brilliant people to follow their curiosity and dream about what the future could bring. To fulfill the potential of quantum technology, we need that spirit of bold adventure now more than ever before. This award honors one scientist, and I’m profoundly grateful for this recognition. But more importantly it serves as a reminder of the vital ongoing need to support the fundamental research that will build foundations for the science and technology of the future. Thank you very much!

August 10, 2025

Nicole’s guide to writing research statements

Sunflowers are blooming, stores are trumpeting back-to-school sales, and professors are scrambling to chart out the courses they planned to develop in July. If you’re applying for an academic job this fall, now is the time to get your application ducks in a row. Seeking a postdoctoral or faculty position? Your applications will center on research statements. Often, a research statement describes your accomplishments and sketches your research plans. What do evaluators look for in such documents? Here’s my advice, which targets postdoctoral fellowships and faculty positions, especially for theoretical physicists.

Keep your audience in mind. Will a quantum information theorist, a quantum scientist, a general physicist, a general scientist, or a general academic evaluate your statement? What do they care about? What technical language do and don’t they understand?What thread unites all the projects you’ve undertaken? Don’t walk through your research history chronologically, stepping from project to project. Cast the key projects in the form of a story—a research program. What vision underlies the program?Here’s what I want to see when I read a description of a completed project.The motivation for the project: This point ensures that the reader will care enough to read the rest of the description.Crucial background informationThe physical setupA statement of the problemWhy the problem is difficult or, if relevant, how long the problem has remained openWhich mathematical toolkit you used to solve the problem or which conceptual insight unlocked the solutionWhich technical or conceptual contribution you providedWhom you collaborated with: Wide collaboration can signal a researcher’s maturity. If you collaborated with researchers at other institutions, name the institutions and, if relevant, their home countries. If you led the project, tell me that, too. If you collaborated with a well-known researcher, mentioning their name might help the reader situate your work within the research landscape they know. But avoid name-dropping, which lacks such a pedagogical purpose and which can come across as crude.Your result’s significance/upshot/applications/impact: Has a lab based an experiment on your theoretical proposal? Does your simulation method outperform its competitors by X% in runtime? Has your mathematical toolkit found applications in three subfields of quantum physics? Consider mentioning whether a competitive conference or journal has accepted your results: QIP, STOC, Physical Review Letters, Nature Physics, etc. But such references shouldn’t serve as a crutch in conveying your results’ significance. You’ll impress me most by dazzling me with your physics; name-dropping venues instead can convey arrogance.Not all past projects deserve the same amount of space. Tell a cohesive story. For example, you might detail one project, then synopsize two follow-up projects in two sentences.A research statement must be high-level, because you don’t have space to provide details. Use mostly prose; and communicate intuition, including with simple examples. But sprinkle in math, such as notation that encapsulates a phrase in one concise symbol.A research statement not only describes past projects, but also sketches research plans. Since research covers terra incognita, though, plans might sound impossible. How can you predict the unknown—especially the next five years of the unknown (as required if you’re applying for a faculty position), especially if you’re a theorist? Show that you’ve developed a map and a compass. Sketch the large-scale steps that you anticipate taking. Which mathematical toolkits will you leverage? What major challenge do you anticipate, and how do you hope to overcome it? Let me know if you’ve undertaken preliminary studies. Do numerical experiments support a theorem you conjecture?When I was applying for faculty positions, a mentor told me the following: many a faculty member can identify a result (or constellation of results) that secured them an offer, as well as a result that earned them tenure. Help faculty-hiring committees identify the offer result and the tenure result.Introduce notation before using it. If you use notation and introduce it afterward, the reader will encounter the notation; stop to puzzle over it; tentatively continue; read the introduction of the notation; return to the earlier use of the notation, to understand it; and then continue forward, including by rereading the introduction of the notation. This back-and-forth breaks up the reading process, which should flow smoothly.Begin every paragraph with a topic sentence. Avoid verbs that fail to relate that you accomplished anything: “studied,” “investigated,” “worked on,” etc. What did you prove, show, demonstrate, solve, calculate, compute, etc.?

Keep your audience in mind. Will a quantum information theorist, a quantum scientist, a general physicist, a general scientist, or a general academic evaluate your statement? What do they care about? What technical language do and don’t they understand?What thread unites all the projects you’ve undertaken? Don’t walk through your research history chronologically, stepping from project to project. Cast the key projects in the form of a story—a research program. What vision underlies the program?Here’s what I want to see when I read a description of a completed project.The motivation for the project: This point ensures that the reader will care enough to read the rest of the description.Crucial background informationThe physical setupA statement of the problemWhy the problem is difficult or, if relevant, how long the problem has remained openWhich mathematical toolkit you used to solve the problem or which conceptual insight unlocked the solutionWhich technical or conceptual contribution you providedWhom you collaborated with: Wide collaboration can signal a researcher’s maturity. If you collaborated with researchers at other institutions, name the institutions and, if relevant, their home countries. If you led the project, tell me that, too. If you collaborated with a well-known researcher, mentioning their name might help the reader situate your work within the research landscape they know. But avoid name-dropping, which lacks such a pedagogical purpose and which can come across as crude.Your result’s significance/upshot/applications/impact: Has a lab based an experiment on your theoretical proposal? Does your simulation method outperform its competitors by X% in runtime? Has your mathematical toolkit found applications in three subfields of quantum physics? Consider mentioning whether a competitive conference or journal has accepted your results: QIP, STOC, Physical Review Letters, Nature Physics, etc. But such references shouldn’t serve as a crutch in conveying your results’ significance. You’ll impress me most by dazzling me with your physics; name-dropping venues instead can convey arrogance.Not all past projects deserve the same amount of space. Tell a cohesive story. For example, you might detail one project, then synopsize two follow-up projects in two sentences.A research statement must be high-level, because you don’t have space to provide details. Use mostly prose; and communicate intuition, including with simple examples. But sprinkle in math, such as notation that encapsulates a phrase in one concise symbol.A research statement not only describes past projects, but also sketches research plans. Since research covers terra incognita, though, plans might sound impossible. How can you predict the unknown—especially the next five years of the unknown (as required if you’re applying for a faculty position), especially if you’re a theorist? Show that you’ve developed a map and a compass. Sketch the large-scale steps that you anticipate taking. Which mathematical toolkits will you leverage? What major challenge do you anticipate, and how do you hope to overcome it? Let me know if you’ve undertaken preliminary studies. Do numerical experiments support a theorem you conjecture?When I was applying for faculty positions, a mentor told me the following: many a faculty member can identify a result (or constellation of results) that secured them an offer, as well as a result that earned them tenure. Help faculty-hiring committees identify the offer result and the tenure result.Introduce notation before using it. If you use notation and introduce it afterward, the reader will encounter the notation; stop to puzzle over it; tentatively continue; read the introduction of the notation; return to the earlier use of the notation, to understand it; and then continue forward, including by rereading the introduction of the notation. This back-and-forth breaks up the reading process, which should flow smoothly.Begin every paragraph with a topic sentence. Avoid verbs that fail to relate that you accomplished anything: “studied,” “investigated,” “worked on,” etc. What did you prove, show, demonstrate, solve, calculate, compute, etc.?Tailor a version of your research statement to every position. Is Fellowship Committee X seeking biophysicists, statistical physicists, mathematical physicists, or interdisciplinary scientists? Also, respect every application’s guidelines about length.If you have room, end the statement with a recap and a statement of significance. Yes, you’ll be repeating ideas mentioned earlier. But your reader’s takeaway hinges on the last text they read. End on a strong note, presenting a coherent vision.

Writing is rewriting, a saying goes. Draft your research statement early, solicit feedback from a couple of mentors, edit the draft, and solicit more feedback.

July 27, 2025

Little ray of sunshine

A common saying goes, you should never meet your heroes, because they’ll disappoint you. But you shouldn’t trust every common saying; some heroes impress you more, the better you know them. Ray Laflamme was such a hero.

I first heard of Ray in my undergraduate quantum-computation course. The instructor assigned two textbooks: the physics-centric “Schumacher and Westmoreland” and “Kaye, Laflamme, and Mosca,” suited to computer scientists. Back then—in 2011—experimentalists were toiling over single quantum logic gates, implemented on pairs and trios of qubits. Some of today’s most advanced quantum-computing platforms, such as ultracold atoms, resembled the scrawnier of the horses at a racetrack. My class studied a stepping stone to those contenders: linear quantum optics (quantum light). Laflamme, as I knew him then, had helped design the implementation.

Imagine my awe upon meeting Ray the following year, as a master’s student at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics. He belonged to Perimeter’s faculty and served as a co-director of the nearby Institute for Quantum Computing (IQC). Ray was slim, had thinning hair of a color similar to mine, and wore rectangular glasses frames. He often wore a smile, too. I can hear his French-Canadian accent in my memory, but not without hearing him smile at the ends of most sentences.

Photo credit: IQC

Photo credit: IQCMy master’s program entailed a research project, which I wanted to center on quantum information theory, one of Ray’s specialties. He met with me and suggested a project, and I began reading relevant papers. I then decided to pursue research with another faculty member and a postdoc, eliminating my academic claim on Ray’s time. But he agreed to keep meeting with me. Heaven knows how he managed; institute directorships devour one’s schedule like ravens dining on a battlefield. Still, we talked approximately every other week.

My master’s program intimidated me, I confessed. It crammed graduate-level courses, which deserved a semester each, into weeks. My class raced through Quantum Field Theory I and Quantum Field Theory II—a year’s worth of material—in part of an autumn. General relativity, condensed matter, and statistical physics swept over us during the same season. I preferred to learn thoroughly, deeply, and using strategies I’d honed over two decades. But I didn’t have time, despite arriving at Perimeter’s library at 8:40 every morning and leaving around 9:30 PM.

In response, Ray confessed that his master’s program had intimidated him. Upon completing his undergraduate degree, Ray viewed himself as a nobody from nowhere. He chafed in the legendary, if idiosyncratically named, program he attended afterward: Part III of the Mathematical Tripos at the University of Cambridge. A Cambridge undergraduate can earn a master’s degree in three steps (tripos) at the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics. Other students, upon completing bachelor’s degrees elsewhere, undertake the third step to earn their master’s. Ray tackled this step, Part III.

He worked his rear off, delving more deeply into course material than lecturers did. Ray would labor over every premise in a theorem’s proof, including when nobody could explain the trickiest step to him.1 A friend and classmate helped him survive. The two studied together, as I studied with a few fellow Perimeter students; and Ray took walks with his friend on Sundays, as I planned lunches with other students on weekends.

Yet the program’s competitiveness appalled Ray. All students’ exam scores appeared on the same piece of paper, posted where everyone could read it. The department would retain the highest scorers in its PhD program; the other students would have to continue their studies elsewhere. Hearing about Ray’s program, I appreciated more than ever the collaboration characteristic of mine.

Ray addressed that trickiest proof step better than he’d feared, come springtime: his name appeared near the top of the exam list. Once he saw the grades, a faculty member notified him that his PhD advisor was waiting upstairs. Ray didn’t recall climbing those stairs, but he found Stephen Hawking at the top.

As one should expect of a Hawking student, Ray studied quantum gravity during his PhD. But by the time I met him, Ray had helped co-found quantum computation. He’d also extended his physics expertise as far from 1980s quantum gravity as one can, by becoming an experimentalist. The nobody from nowhere had earned his wings—then invented novel wings that nobody had dreamed of. But he descended from the heights every other week, to tell stories to a nobody of a master’s student.

The author’s copy of “Kaye, Laflamme, and Mosca”…

The author’s copy of “Kaye, Laflamme, and Mosca”…

…in good company.

…in good company.Seven and a half years later, I advertised openings in the research group I was establishing in Maryland. A student emailed from the IQC, whose co-directorship Ray had relinquished in 2017. The student had seen me present a talk, it had inspired him to switch fields into quantum thermodynamics, and he asked me to co-supervise his PhD. His IQC supervisor had blessed the request: Ray Laflamme.

The student was Shayan Majidy, now a postdoc at Harvard. Co-supervising him with Ray Laflamme reminded me of cooking in the same kitchen as Julia Child. I still wonder how I, green behind the ears, landed such a gig. Shayan delighted in describing the difference between his supervisors’ advising styles. An energetic young researcher,2 I’d respond to emails as early as 6:00 AM. I’d press Shayan about literature he’d read, walk him through what he hadn’t grasped, and toss a paper draft back and forth with him multiple times per day. Ray, who’d mellowed during his career, mostly poured out support and warmth like hollandaise sauce.

Once, Shayan emailed Ray and me to ask if he could take a vacation. I responded first, as laconically as my PhD advisor would have: “Have fun!” Ray replied a few days later. He elaborated on his pleasure at Shayan’s plans and on how much Shayan deserved the break.

When I visited Perimeter in 2022, Shayan insisted on a selfie with both his PhD advisors.

When I visited Perimeter in 2022, Shayan insisted on a selfie with both his PhD advisors.This June, an illness took Ray earlier than expected. We physicists lost an intellectual explorer, a co-founder of the quantum-computing community, and a scientist of my favorite type: a wonderful physicist who was a wonderful human being. Days after he passed, I was holed up in a New York hotel room, wincing over a web search. I was checking whether a quantum system satisfies certain tenets of quantum error correction, and we call those tenets the Knill–Laflamme conditions. Our community will keep checking the Knill–Laflamme conditions, keep studying quantum gates implementable with linear optics, and more. Part of Ray won’t leave us anytime soon—the way he wouldn’t leave a nobody of a master’s student who needed a conversation.

1For the record, some of the most rigorous researchers I know work in Cambridge’s Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics today. I’ve even blogged about some.

2As I still am, thank you very much.

June 22, 2025

A (quantum) complex legacy: Part trois

When I worked in Cambridge, Massachusetts, a friend reported that MIT’s postdoc association had asked its members how it could improve their lives. The friend confided his suggestion to me: throw more parties.1 This year grants his wish on a scale grander than any postdoc association could. The United Nations has designated 2025 as the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ), as you’ve heard unless you live under a rock (or without media access—which, come to think of it, sounds not unappealing).

A metaphorical party cracker has been cracking since January. Governments, companies, and universities are trumpeting investments in quantum efforts. Institutions pulled out all the stops for World Quantum Day, which happens every April 14 but which scored a Google doodle this year. The American Physical Society (APS) suffused its Global Physics Summit in March with quantum science like a Bath & Body Works shop with the scent of Pink Pineapple Sunrise. At the summit, special symposia showcased quantum research, fellow blogger John Preskill dished about quantum-science history in a dinnertime speech, and a “quantum block party” took place one evening. I still couldn’t tell you what a quantum block party is, but this one involved glow sticks.

Google doodle from April 14, 2025

Google doodle from April 14, 2025Attending the summit, I felt a satisfaction—an exultation, even—redolent of twelfth grade, when American teenagers summit the Mont Blanc of high school. It was the feeling that this year is our year. Pardon me while I hum “Time of your life.”2

Speakers and organizer of a Kavli Symposium, a special session dedicated to interdisciplinary quantum science, at the APS Global Physics Summit

Speakers and organizer of a Kavli Symposium, a special session dedicated to interdisciplinary quantum science, at the APS Global Physics SummitJust before the summit, editors of the journal PRX Quantum released a special collection in honor of the IYQ.3 The collection showcases a range of advances, from chemistry to quantum error correction and from atoms to attosecond-length laser pulses. Collaborators and I contributed a paper about quantum complexity, a term that has as many meanings as companies have broadcast quantum news items within the past six months. But I’ve already published two Quantum Frontiers posts about complexity, and you surely study this blog as though it were the Bible, so we’re on the same page, right?

Just joshing.

Imagine you have a quantum computer that’s running a circuit. The computer consists of qubits, such as atoms or ions. They begin in a simple, “fresh” state, like a blank notebook. Post-circuit, they store quantum information, such as entanglement, as a notebook stores information post-semester. We say that the qubits are in some quantum state. The state’s quantum complexity is the least number of basic operations, such as quantum logic gates, needed to create that state—via the just-completed circuit or any other circuit.

Today’s quantum computers can’t create high-complexity states. The reason is, every quantum computer inhabits an environment that disturbs the qubits. Air molecules can bounce off them, for instance. Such disturbances corrupt the information stored in the qubits. Wait too long, and the environment will degrade too much of the information for the quantum computer to work. We call the threshold time the qubits’ lifetime, among more-obscure-sounding phrases. The lifetime limits the number of gates we can run per quantum circuit.

The ability to perform many quantum gates—to perform high-complexity operations—serves as a resource. Other quantities serve as resources, too, as you’ll know if you’re one of the three diehard Quantum Frontiers fans who’ve been reading this blog since 2014 (hi, Mom). Thermodynamic resources include work: coordinated energy that one can harness directly to perform a useful task, such as lifting a notebook or staying up late enough to find out what a quantum block party is.

My collaborators: Jonas Haferkamp, Philippe Faist, Teja Kothakonda, Jens Eisert, and Anthony Munson (in an order of no significance here)

My collaborators: Jonas Haferkamp, Philippe Faist, Teja Kothakonda, Jens Eisert, and Anthony Munson (in an order of no significance here)My collaborators and I showed that work trades off with complexity in information- and energy-processing tasks: the more quantum gates you can perform, the less work you have to spend on a task, and vice versa. Qubit reset exemplifies such tasks. Suppose you’ve filled a notebook with a calculation, you want to begin another calculation, and you have no more paper. You have to erase your notebook. Similarly, suppose you’ve completed a quantum computation and you want to run another quantum circuit. You have to reset your qubits to a fresh, simple state.

Three methods suggest themselves. First, you can “uncompute,” reversing every quantum gate you performed.4 This strategy requires a long lifetime: the information imprinted on the qubits by a gate mustn’t leak into the environment before you’ve undone the gate.

Second, you can do the quantum equivalent of wielding a Pink Pearl Paper Mate: you can rub the information out of your qubits, regardless of the circuit you just performed. Thermodynamicists inventively call this strategy erasure. It requires thermodynamic work, just as applying a Paper Mate to a notebook does.

Third, you can

Suppose your qubits have finite lifetimes. You can undo as many gates as you have time to. Then, you can erase the rest of the qubits, spending work. How does complexity—your ability to perform many gates—trade off with work? My collaborators and I quantified the tradeoff in terms of an entropy we invented because the world didn’t have enough types of entropy.5

Complexity trades off with work not only in qubit reset, but also in data compression and likely other tasks. Quantum complexity, my collaborators and I showed, deserves a seat at the great soda fountain of quantum thermodynamics.

The great soda fountain of quantum thermodynamics

The great soda fountain of quantum thermodynamics…as quantum information science deserves a seat at the great soda fountain of physics. When I embarked upon my PhD, faculty members advised me to undertake not only quantum-information research, but also some “real physics,” such as condensed matter. The latter would help convince physics departments that I was worth their money when I applied for faculty positions. By today, the tables have turned. A condensed-matter theorist I know has wound up an electrical-engineering professor because he calculates entanglement entropies.

So enjoy our year, fellow quantum scientists. Party like it’s 1925. Burnish those qubits—I hope they achieve the lifetimes of your life.

1Ten points if you can guess who the friend is.

2Whose official title, I didn’t realize until now, is “Good riddance.” My conception of graduation rituals has just turned a somersault.

3PR stands for Physical Review, the brand of the journals published by the APS. The APS may have intended for the X to evoke exceptional, but I like to think it stands for something more exotic-sounding, like ex vita discedo, tanquam ex hospitio, non tanquam ex domo.

4Don’t ask me about the notebook analogue of uncomputing a quantum state. Explaining it would require another blog post.

5For more entropies inspired by quantum complexity, see this preprint. You might recognize two of the authors from earlier Quantum Frontiers posts if you’re one of the three…no, not even the three diehard Quantum Frontiers readers will recall; but trust me, two of the authors have received nods on this blog before.

June 9, 2025

Congratulations, class of 2025! Words from a new graduate

Editor’s note (Nicole Yunger Halpern): Jade LeSchack, the Quantum Steampunk Laboratory’s first undergraduate, received her bachelor’s degree from the University of Maryland this spring. Kermit the Frog presented the valedictory address, but Jade gave the following speech at the commencement ceremony for the university’s College of Mathematical and Natural Sciences. Jade heads to the University of Southern California for a PhD in physics this fall.

Good afternoon, everyone. My name is Jade, and it is my honor and pleasure to speak before you.

Today, I’m graduating with my Bachelor of Science, but when I entered UMD, I had no idea what it meant to be a professional scientist or where my passion for quantum science would take me. I want you to picture where you were four years ago. Maybe you were following a long-held passion into college, or maybe you were excited to explore a new technical field. Since then, you’ve spent hours titrating solutions, debugging code, peering through microscopes, working out proofs, and all the other things our disciplines require of us. Now, we’re entering a world of uncertainty, infinite possibility, and lifelong connections. Let me elaborate on each of these.

First, there is uncertainty. Unlike simplified projectile motion, you can never predict the exact trajectory of your life or career. Plans will change, and unexpected opportunities will arise. Sometimes, the best path forward isn’t the one you first imagined. Our experiences at Maryland have prepared us to respond to the challenges and curveballs that life will throw at us. And, we’re going to get through the rough patches.

Second, let’s embrace the infinite possibilities ahead of us. While the concept of the multiverse is best left to the movies, it’s exciting to think about all the paths before us. We’ve each found our own special interests over the past four years here, but there’s always more to explore. Don’t put yourself in a box. You can be an artist and a scientist, an entrepreneur and a humanitarian, an athlete and a scholar. Continue to redefine yourself and be open to your infinite potential.

Third, as we move forward, we are equipped not only with knowledge but with connections. We’ve made lasting relationships with incredible people here. As we go from place to place, the people who we’re close to will change. But we’re lucky that, these days, people are only an email or phone call away. We’ll always have our UMD communities rooting for us.

Now, the people we met here are certainly not the only important ones. We’ve each had supporters along the various stages of our journeys. These are the people who championed us, made sacrifices for us, and gave us a shoulder to cry on. I’d like to take a moment to thank all my mentors, teachers, and friends for believing in me. To my mom, dad, and sister sitting up there, I couldn’t have done this without you. Thank you for your endless love and support.

To close, I’d like to consider this age-old question that has always fascinated me: Is mathematics discovered or invented? People have made a strong case for each side. If we think about science in general, and our future contributions to our fields, we might ask ourselves: Are we discoverers or inventors? My answer is both! Everyone here with a cap on their head is going to contribute to both. We’re going to unearth new truths about nature and innovate scientific technologies that better society. This uncertain, multitudinous, and interconnected world is waiting for us, the next generation of scientific thinkers! So let’s be bold and stay fearless.

Congratulations to the class of 2024 and the class of 2025! We did it!

Author’s note: I was deeply grateful for the opportunity to serve as the student speaker at my commencement ceremony. I hope that the science-y references tickle the layman and SME alike. You can view a recording of the speech here. I can’t wait for my next adventures in quantum physics!

May 27, 2025

I know I am but what are you? Mind and Matter in Quantum Mechanics

Nowadays it is best to exercise caution when bringing the words “quantum” and “consciousness” anywhere near each other, lest you be suspected of mysticism or quackery. Eugene Wigner did not concern himself with this when he wrote his “Remarks on the Mind-Body Question” in 1967. (Perhaps he was emboldened by his recent Nobel prize for contributions to the mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics, which gave him not a little no-nonsense technical credibility.) The mind-body question he addresses is the full-blown philosophical question of “the relation of mind to body”, and he argues unapologetically that quantum mechanics has a great deal to say on the matter. The workhorse of his argument is a thought experiment that now goes by the name “Wigner’s Friend”. About fifty years later, Daniela Frauchiger and Renato Renner formulated another, more complex thought experiment to address related issues in the foundations of quantum theory. In this post, I’ll introduce Wigner’s goals and argument, and evaluate Frauchiger’s and Renner’s claims of its inadequacy, concluding that these are not completely fair, but that their thought experiment does do something interesting and distinct. Finally, I will describe a recent paper of my own, in which I formalize the Frauchiger-Renner argument in a way that illuminates its status and isolates the mathematical origin of their paradox.

* * *

Wigner takes a dualist view about the mind, that is, he believes it to be non-material. To him this represents the common-sense view, but is nevertheless a newly mainstream attitude. Indeed,

[until] not many years ago, the “existence” of a mind or soul would have been passionately denied by most physical scientists. The brilliant successes of mechanistic and, more generally, macroscopic physics and of chemistry overshadowed the obvious fact that thoughts, desires, and emotions are not made of matter, and it was nearly universally accepted among physical scientists that there is nothing besides matter.

He credits the advent of quantum mechanics with

the return, on the part of most physical scientists, to the spirit of Descartes’s “Cogito ergo sum”, which recognizes the thought, that is, the mind, as primary. [With] the creation of quantum mechanics, the concept of consciousness came to the fore again: it was not possible to formulate the laws of quantum mechanics in a fully consistent way without reference to the consciousness.

What Wigner has in mind here is that the standard presentation of quantum mechanics speaks of definite outcomes being obtained when an observer makes a measurement. Of course this is also true in classical physics. In quantum theory, however, the principles of linear evolution and superposition, together with the plausible assumption that mental phenomena correspond to physical phenomena in the brain, lead to situations in which there is no mechanism for such definite observations to arise. Thus there is a tension between the fact that we would like to ascribe particular observations to conscious agents and the fact that we would like to view these observations as corresponding to particular physical situations occurring in their brains.

Once we have convinced ourselves that, in light of quantum mechanics, mental phenomena must be considered on an equal footing with physical phenomena, we are faced with the question of how they interact. Wigner takes it for granted that “if certain physico-chemical conditions are satisfied, a consciousness, that is, the property of having sensations, arises.” Does the influence run the other way? Wigner claims that the “traditional answer” is that it does not, but argues that in fact such influence ought indeed to exist. (Indeed this, rather than technical investigation of the foundations of quantum mechanics, is the central theme of his essay.) The strongest support Wigner feels he can provide for this claim is simply “that we do not know of any phenomenon in which one subject is influenced by another without exerting an influence thereupon”. Here he recalls the interaction of light and matter, pointing out that while matter obviously affects light, the effects of light on matter (for example radiation pressure) are typically extremely small in magnitude, and might well have been missed entirely had they not been suggested by the theory.

Quantum mechanics provides us with a second argument, in the form of a demonstration of the inconsistency of several apparently reasonable assumptions about the physical, the mental, and the interaction between them. Wigner works, at least implicitly, within a model where there are two basic types of object: physical systems and consciousnesses. Some physical systems (those that are capable of instantiating the “certain physico-chemical conditions”) are what we might call mind-substrates. Each consciousness corresponds to a mind-substrate, and each mind-substrate corresponds to at most one consciousness. He considers three claims (this organization of his premises is not explicit in his essay):

1. Isolated physical systems evolve unitarily.

2. Each consciousness has a definite experience at all times.

3. Definite experiences correspond to pure states of mind-substrates, and arise for a consciousness exactly when the corresponding mind-substrate is in the corresponding pure state.

The first and second assumptions constrain the way the model treats physical and mental phenomena, respectively. Assumption 1 is often paraphrased as the `”completeness of quantum mechanics”, while Assumption 2 is a strong rejection of solipsism – the idea that only one’s own mind is sure to exist. Assumption 3 is an apparently reasonable assumption about the relation between mental and physical phenomena.

With this framework established, Wigner’s thought experiment, now typically known as Wigner’s Friend, is quite straightforward. Suppose that an observer, Alice (to name the friend), is able to perform a measurement of some physical quantity  of a particle, which may take two values,

of a particle, which may take two values,  and

and  . Assumption 1 tells us that if Alice performs this measurement when the particle is in a superposition state, the joint system of Alice’s brain and the particle will end up in an entangled state. Now Alice’s mind-substrate is not in a pure state, so by Assumption 3 does not have a definite experience. This contradicts Assumption 2. Wigner’s proposed resolution to this paradox is that in fact Assumption 1 is incorrect, and that there is an influence of the mental on the physical, namely objective collapse or, as he puts it, that the “statistical element which, according to the orthodox theory, enters only if I make an observation enters equally if my friend does”.

. Assumption 1 tells us that if Alice performs this measurement when the particle is in a superposition state, the joint system of Alice’s brain and the particle will end up in an entangled state. Now Alice’s mind-substrate is not in a pure state, so by Assumption 3 does not have a definite experience. This contradicts Assumption 2. Wigner’s proposed resolution to this paradox is that in fact Assumption 1 is incorrect, and that there is an influence of the mental on the physical, namely objective collapse or, as he puts it, that the “statistical element which, according to the orthodox theory, enters only if I make an observation enters equally if my friend does”.

* * *

Decades after the publication of Wigner’s essay, Daniela Frauchiger and Renato Renner formulated a new thought experiment, involving observers making measurements of other observers, which they intended to remedy what they saw as a weakness in Wigner’s argument. In their words, “Wigner proposed an argument […] which should show that quantum mechanics cannot have unlimited validity”. In fact, they argue, Wigner’s argument does not succeed in doing so. They assert that Wigner’s paradox may be resolved simply by noting a difference in what each party knows. Whereas Wigner, describing the situation from the outside, does not initially know the result of his friend’s measurement, and therefore assigns the “absurd” entangled state to the joint system composed of both her body and the system she has measured, his friend herself is quite aware of what she has observed, and so assigns to the system either, but not both, of the states corresponding to definite measurement outcomes. “For this reason”, Frauchiger and Renner argue, “the Wigner’s Friend Paradox cannot be regarded as an argument that rules out quantum mechanics as a universally valid theory.”

This criticism strikes me as somewhat unfair to Wigner. In fact, Wigner’s objection to admitting two different states as equally valid descriptions is that the two states correspond to different sets of \textit{physical} properties of the joint system consisting of Alice and the system she measures. For Wigner, physical properties of physical systems are distinct from mental properties of consciousnesses. To engage in some light textual analysis, we can note that the word ‘conscious’, or ‘consciousness’, appears forty-one times in Wigner’s essay, and only once in Frauchiger and Renner’s, in the title of a cited paper. I have the impression that the authors pay inadequate attention to how explicitly Wigner takes a dualist position, including not just physical systems but also, and distinctly, consciousnesses in his ontology. Wigner’s argument does indeed achieve his goals, which are developed in the context of this strong dualism, and differ from the goals of Frauchiger and Renner, who appear not to share this philosophical stance, or at least do not commit fully to it.

Nonetheless, the thought experiment developed by Frauchiger and Renner does achieve something distinct and interesting. We can understand Wigner’s no-go theorem to be of the following form: “Within a model incorporating both mental and physical phenomena, a set of apparently reasonable conditions on how the model treats physical phenomena, mental phenomena, and their interaction cannot all be satisfied”. The Frauchiger-Renner thought experiment can be cast in the same form, with different choices about how to implement the model and which conditions to consider. The major difference in the model itself is that Frauchiger and Renner do not take consciousnesses to be entities in their own rights, but simply take some states of certain physical systems to correspond to conscious experiences. Within such a model, Wigner’s assumption that each mind has a single, definite conscious experience at all times seems far less natural than it did within his model, where consciousnesses are distinct entities from the physical systems that determine them. Thus Frauchiger and Renner need to weaken this assumption, which was so natural to Wigner. The weakening they choose is a sort of transitivity of theories of mind. In their words (Assumption C in their paper):

Suppose that agent A has established that “I am certain that agent A’, upon reasoning within the same theory as the one I am using, is certain that

at time

.” Then agent A can conclude that “I am certain that

at time

.”

Just as Assumption 3 above was, for Wigner, a natural restriction on how a sensible theory ought to treat mental phenomena, this serves as Frauchiger’s and Renner’s proposed constraint. Just as Wigner designed a thought experiment that demonstrated the incompatibility of his assumption with an assumption of the universal applicability of unitary quantum mechanics to physical systems, so do Frauchiger and Renner.

* * *

In my recent paper “Reasoning across spacelike surfaces in the Frauchiger-Renner thought experiment”, I provide two closely related formalizations of the Frauchiger-Renner argument. These are motivated by a few observations:

1. Assumption C ought to make reference to the (possibly different) times at which agents  and

and  are certain about their respective judgments, since these states of knowledge change.

are certain about their respective judgments, since these states of knowledge change.

2. Since Frauchiger and Renner do not subscribe to Wigner’s strong dualism, an agent’s certainty about a given proposition, like any other mental state, corresponds within their implicit model to a physical state. Thus statements like “Alice knows that P” should be understood as statements about the state of some part of Alice’s brain. Conditional statements like “if upon measuring a quantity q Alice observes outcome  , she knows that P” should be understood as claims about the state of the composite system composed of the part of Alice’s brain responsible for knowing P and the part responsible for recording outcomes of the measurement of q.

, she knows that P” should be understood as claims about the state of the composite system composed of the part of Alice’s brain responsible for knowing P and the part responsible for recording outcomes of the measurement of q.

3. Because the causal structure of the protocol does not depend on the absolute times of each event, an external agent describing the protocol can choose various “spacelike surfaces”, corresponding to fixed times in different spacetime embeddings of the protocol (or to different inertial frames). There is no reason to privilege one of these surfaces over another, and so each of them should be assigned a quantum state. This may be viewed as an implementation of a relativistic principle.

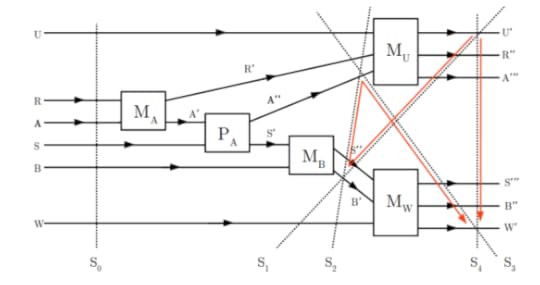

A visual representation of the formalization of the Frauchiger-Renner protocol and the arguments of the no-go theorem. The graphical conventions are explained in detail in “Reasoning across spacelike surfaces in the Frauchiger-Renner thought experiment”.

A visual representation of the formalization of the Frauchiger-Renner protocol and the arguments of the no-go theorem. The graphical conventions are explained in detail in “Reasoning across spacelike surfaces in the Frauchiger-Renner thought experiment”.After developing a mathematical framework based on these observations, I recast Frauchiger’s and Renner’s Assumption C in two ways: first, in terms of a claim about the validity of iterating the “relative state” construction that captures how conditional statements are interpreted in terms of quantum states; and second, in terms of a deductive rule that allows chaining of inferences within a system of quantum logic. By proving that these claims are false in the mathematical framework, I provide a more formal version of the no-go theorem. I also show that the first claim can be rescued if the relative state construction is allowed to be iterated only “along” a single spacelike surface, and the second if a deduction is only allowed to chain inferences “along” a single surface. In other words, the mental transitivity condition desired by Frauchiger and Renner can in fact be combined with universal physical applicability of unitary quantum mechanics, but only if we restrict our analysis to a single spacelike surface. Thus I hope that the analysis I offer provides some clarification of what precisely is going on in Frauchiger and Renner’s thought experiment, what it tells us about combining the physical and the mental in light of quantum mechanics, and how it relates to Wigner’s thought experiment.

* * *

In view of the fact that “Quantum theory cannot consistently describe the use of itself” has, at present, over five hundred citations, and “Remarks on the Mind-Body Question” over thirteen hundred, it seems fitting to close with a thought, cautionary or exultant, from Peter Schwenger’s book on asemic, that is meaningless, writing. He notes that

commentary endlessly extends language; it is in the service of an impossible quest to extract the last, the final, drop of meaning.

I provide no analysis of this claim.

May 25, 2025

The most steampunk qubit

I never imagined that an artist would update me about quantum-computing research.

Last year, steampunk artist Bruce Rosenbaum forwarded me a notification about a news article published in Science. The article reported on an experiment performed in physicist Yiwen Chu’s lab at ETH Zürich. The experimentalists had built a “mechanical qubit”: they’d stored a basic unit of quantum information in a mechanical device that vibrates like a drumhead. The article dubbed the device a “steampunk qubit.”

I was collaborating with Bruce on a quantum-steampunk sculpture, and he asked if we should incorporate the qubit into the design. Leave it for a later project, I advised. But why on God’s green Earth are you receiving email updates about quantum computing?

My news feed sends me everything that says “steampunk,” he explained. So keeping a bead on steampunk can keep one up to date on quantum science and technology—as I’ve been preaching for years.

Other ideas displaced Chu’s qubit in my mind until I visited the University of California, Berkeley this January. Visiting Berkeley in January, one can’t help noticing—perhaps with a trace of smugness—the discrepancy between the temperature there and the temperature at home. And how better to celebrate a temperature difference than by studying a quantum-thermodynamics-style throwback to the 1800s?

One sun-drenched afternoon, I learned that one of my hosts had designed another steampunk qubit: Alp Sipahigil, an assistant professor of electrical engineering. He’d worked at Caltech as a postdoc around the time I’d finished my PhD there. We’d scarcely interacted, but I’d begun learning about his experiments in atomic, molecular, and optical physics then. Alp had learned about my work through Quantum Frontiers, as I discovered this January. I had no idea that he’d “met” me through the blog until he revealed as much to Berkeley’s physics department, when introducing the colloquium I was about to present.

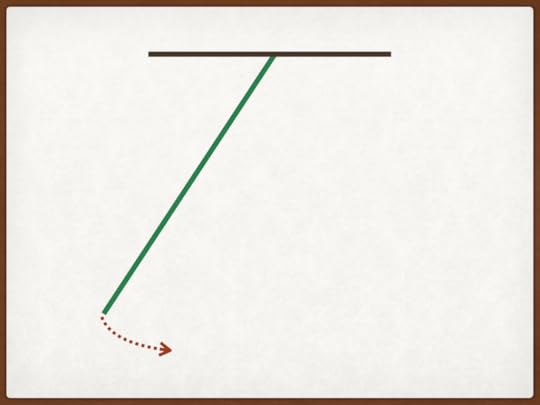

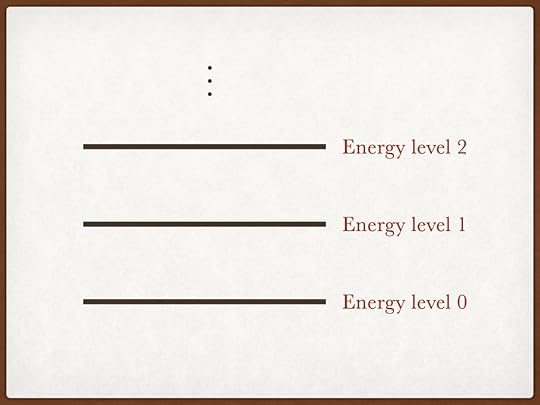

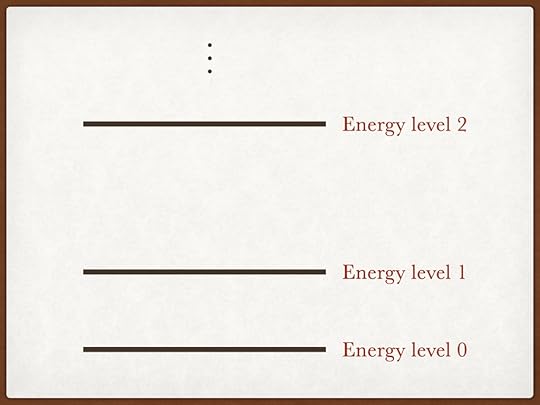

Alp and collaborators proposed that a qubit could work as follows. It consists largely of a cantilever, which resembles a pendulum that bobs back and forth. The cantilever, being quantum, can have only certain amounts of energy. When the pendulum has a particular amount of energy, we say that the pendulum is in a particular energy level.

One might hope to use two of the energy levels as a qubit: if the pendulum were in its lowest-energy level, the qubit would be in its 0 state; and the next-highest level would represent the 1 state. A bit—a basic unit of classical information—has 0 and 1 states. A qubit can be in a superposition of 0 and 1 states, and so the cantilever could be.

A flaw undermines this plan, though. Suppose we want to process the information stored in the cantilever—for example, to turn a 0 state into a 1 state. We’d inject quanta—little packets—of energy into the cantilever. Each quantum would contain an amount of energy equal to (the energy associated with the cantilever’s 1 state) – (the amount associated with the 0 state). This equality would ensure that the cantilever could accept the energy packets lobbed at it.

But the cantilever doesn’t have only two energy levels; it has loads. Worse, all the inter-level energy gaps equal each other. However much energy the cantilever consumes when hopping from level 0 to level 1, it consumes that much when hopping from level 1 to level 2. This pattern continues throughout the rest of the levels. So imagine starting the cantilever in its 0 level, then trying to boost the cantilever into its 1 level. We’d probably succeed; the cantilever would probably consume a quantum of energy. But nothing would stop the cantilever from gulping more quanta and rising to higher energy levels. The cantilever would cease to serve as a qubit.

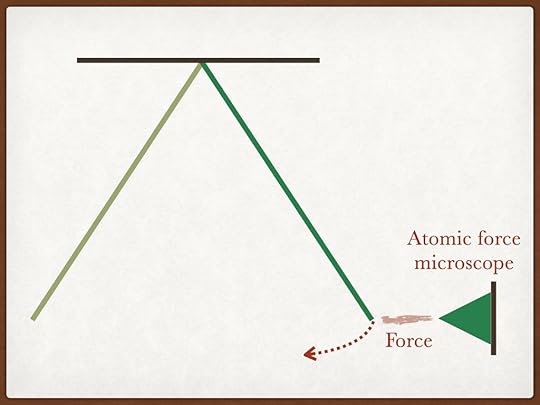

We can avoid this problem, Alp’s team proposed, by placing an atomic-force microscope near the cantilever. An atomic force microscope maps out surfaces similarly to how a Braille user reads: by reaching out a hand and feeling. The microscope’s “hand” is a tip about ten nanometers across. So the microscope can feel surfaces far more fine-grained than a Braille user can. Bumps embossed on a page force a Braille user’s finger up and down. Similarly, the microscope’s tip bobs up and down due to forces exerted by the object being scanned.

Imagine placing a microscope tip such that the cantilever swings toward it and then away. The cantilever and tip will exert forces on each other, especially when the cantilever swings close. This force changes the cantilever’s energy levels. Alp’s team chose the tip’s location, the cantilever’s length, and other parameters carefully. Under the chosen conditions, boosting the cantilever from energy level 1 to level 2 costs more energy than boosting from 0 to 1.

So imagine, again, preparing the cantilever in its 0 state and injecting energy quanta. The cantilever will gobble a quantum, rising to level 1. The cantilever will then remain there, as desired: to rise to level 2, the cantilever would have to gobble a larger energy quantum, which we haven’t provided.1

Will Alp build the mechanical qubit proposed by him and his collaborators? Yes, he confided, if he acquires a student nutty enough to try the experiment. For when he does—after the student has struggled through the project like a dirigible through a hurricane, but ultimately triumphed, and a journal is preparing to publish their magnum opus, and they’re brainstorming about artwork to represent their experiment on the journal’s cover—I know just the aesthetic to do the project justice.

1Chu’s team altered their cantilever’s energy levels using a superconducting qubit, rather than an atomic force microscope.