Beth Kephart's Blog, page 267

December 22, 2010

The Last Brother/by Nathacha Appanah: Reflections

There is a boy named Raj, and he is nine years old. He lives in Mauritius; it is 1944. Raj was the middle son of three, but now he is the family's only son, and what, he asks us, is the word for a boy who loses both his brothers in one day? What is the word for a boy whose love will be even more strenuously tested? What is the capability and culpability of memory when an old man looks back and remembers?

There is a boy named Raj, and he is nine years old. He lives in Mauritius; it is 1944. Raj was the middle son of three, but now he is the family's only son, and what, he asks us, is the word for a boy who loses both his brothers in one day? What is the word for a boy whose love will be even more strenuously tested? What is the capability and culpability of memory when an old man looks back and remembers?This is the Raj of Nathacha Appanah's extraordinary novel, The Last Brother (Graywolf Press, translated by Geoffrey Strachan). This is the landscape of a book that will take you deeply and unforgettably into the abundant and cruel Mauritius, into the childhood of one fated with a violent father and a healing mother, into the topography of bewildering loss. In The Last Brother Raj is an old man looking back on a friendship that erupted, mysteriously, during his ninth year—a friendship between himself and a boy named David, a blond Jewish exile whom he meets in the hospital ward of an island prison. Raj then and now is haunted, confused. He wants to know, precisely. He wants to honor the past by reviving its details, by not looking away—but can he? Can any of us?

The artfulness of this novel is directly tied to the lack of pretense in Raj's narrating voice—the tangles he gets himself into, the sentences that smudge punctuation, change tense, get lost in the scribble of time. What does it mean to write authentically? I think it means recognizing that an old man looking back on an exotic, fated childhood might remember and recall the world, without artifice, this way:

During those says spent all alone at Beau-Bassin, immersed in that somehow muted light, which now took on the color of the forest, now the color of the flowers my mother had planted around the house to crate a benign ring, or else that of the bluish mountains in the distance, I discovered a taste for hiding places. I would lie low in corners, tucking my feet and legs in underneath me, I would climb up into trees and crouch in the forks of branches, my body coiled in on itself like a snake, I would dig holes beneath the squash plants in the vegetable garden and crawl in there, with my belly to the ground, my hands buried in the earth up to my wrists, my face hidden among the creepers.The Last Brother, already hailed internationally, is due out in the States in February from Graywolf Press. I was blessed to receive an early copy from the press itself. Sent to me because they know, at Graywolf, that I love great books. I hold them to my heart.

Published on December 22, 2010 14:03

December 21, 2010

If I can write the story

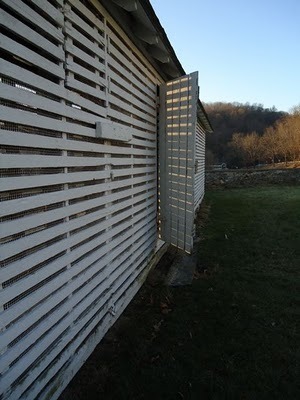

(if there is room, if there is time, if my thoughts will multiply, then settle), part of it will happen here. I drove my son to this spot a few days ago. He declared it good novel material.

(if there is room, if there is time, if my thoughts will multiply, then settle), part of it will happen here. I drove my son to this spot a few days ago. He declared it good novel material.

Published on December 21, 2010 05:00

December 20, 2010

In which my niece takes me to southern Spain (for a moment)

My niece just called and we had the nicest conversation for the longest, sweetest time. She's home with a cold, curled up in her bed with a stack of new books by her side, and she's done what we lovers of books all do—read the first few pages of each open option first, chosen one, and settled in. Two of her cats are nearby. Her shelf of personal books (so stuffed full she worries it will sink straight through the floor) stands near. Her heart and mind are primed for adventure, and so today, reading in bed, she will have one and, because she called, I was having (a very nice) one. Our conversation was nearing its end when Claire said that she had one more question for me: What part of the world did I really, really want to see next?

My niece just called and we had the nicest conversation for the longest, sweetest time. She's home with a cold, curled up in her bed with a stack of new books by her side, and she's done what we lovers of books all do—read the first few pages of each open option first, chosen one, and settled in. Two of her cats are nearby. Her shelf of personal books (so stuffed full she worries it will sink straight through the floor) stands near. Her heart and mind are primed for adventure, and so today, reading in bed, she will have one and, because she called, I was having (a very nice) one. Our conversation was nearing its end when Claire said that she had one more question for me: What part of the world did I really, really want to see next?"Oh," I said, sighing, and then there we were, the two of us, adventuring again—just words, just hopes, just our all-color, all afloat, ours alone imaginations.

Published on December 20, 2010 07:09

December 19, 2010

(My) Imprints of the Year

At the close of this year, I'd like to sidestep the naming of favorite books to honor two imprints instead—imprints whose books most advance my faith in publishing and occupy much of my shelf space. The first, of course, is Graywolf Press, which publishes my dear friend Alyson Hagy (Ghosts of Wyoming), introduced me to my now-friend Jessica Francis Kane (The Report), publishes the brilliant Per Petterson (I Curse the River of Time), puts out books that consistently surprise me (take Vanishing Point, that fascinating riff on memoir by Ander Monson), and celebrates some of the best poets of our day (Jane Kenyon, Linda Gregg, Carl Phillips, Thomas Sayers Ellis). Look for The Last Brother, a Nathacha Appanah novel being released from Graywolf in February. I started the book this morning. It is going to be an everlasting favorite.

At the close of this year, I'd like to sidestep the naming of favorite books to honor two imprints instead—imprints whose books most advance my faith in publishing and occupy much of my shelf space. The first, of course, is Graywolf Press, which publishes my dear friend Alyson Hagy (Ghosts of Wyoming), introduced me to my now-friend Jessica Francis Kane (The Report), publishes the brilliant Per Petterson (I Curse the River of Time), puts out books that consistently surprise me (take Vanishing Point, that fascinating riff on memoir by Ander Monson), and celebrates some of the best poets of our day (Jane Kenyon, Linda Gregg, Carl Phillips, Thomas Sayers Ellis). Look for The Last Brother, a Nathacha Appanah novel being released from Graywolf in February. I started the book this morning. It is going to be an everlasting favorite.The second honorable, wonderful, heart dance of an imprint is Black Cat, of Grove Atlantic, which publishes some of the most beautiful original trade paperback novels and nonfiction I've ever seen. I first started connecting the imprint itself to actual book titles when I read Chloe Aridjis's Book of Clouds, an utterly sensational and surreal portrait of Berlin. More fabulous Black Cat titles came my way (an angel sent them), and I was hooked. This year The Disappeared by Kim Echlin engulfed me. I laughed hard at Steve Hely's How I Became a Famous Novelist, and for Christmas I am buying myself Vida, the Patricia Engle story collection that was named one of the 100 Notable Books of the Year by the Times.

The end of real literature is not near. It lives among gray wolves and black cats.

Published on December 19, 2010 05:37

December 18, 2010

Scenes from the same day (later)

Published on December 18, 2010 15:46

Scenes from the day

Published on December 18, 2010 09:44

Dave Eggers on (in) The Writing Life

All right, so I didn't see this rocking Dave Eggers (Washington Post) essay until just now, but maybe you do, actually, find things when you need things, and at 5:08 AM this Saturday before Christmas morn, I needed this. I needed Eggers winding through his idea of the writing life like this—urging us to fidget and beguiling us with tales of what happens when teens read something they love. They get excited. They say what they think. They press the words to their hearts. They inspire us writers who spend too much of too many days inside the lonely alone of striving. "Their reactions can be hard to predict," writes Eggers, "and they're always brutally honest, but when they love something, their enthusiasm is completely without guile, utterly without cynicism."

All right, so I didn't see this rocking Dave Eggers (Washington Post) essay until just now, but maybe you do, actually, find things when you need things, and at 5:08 AM this Saturday before Christmas morn, I needed this. I needed Eggers winding through his idea of the writing life like this—urging us to fidget and beguiling us with tales of what happens when teens read something they love. They get excited. They say what they think. They press the words to their hearts. They inspire us writers who spend too much of too many days inside the lonely alone of striving. "Their reactions can be hard to predict," writes Eggers, "and they're always brutally honest, but when they love something, their enthusiasm is completely without guile, utterly without cynicism."I love Eggers for committing so much of his time to younger writers and readers. I love him for reporting out from this work. I love him for expressing so well what I feel myself, for I don't think I'd have made it through the past two weeks without kids—the young poets of Baldwin, the talented yearners of Norristown High, the utterly sensational personifiers of T/E Middle School. They save me, these kids, every time. They shake me from my fever, they restore my faith in now, they give me a reason to keep writing toward the real and daring—to keep hoping for the real and daring—when so much of my life is not about that at all.

Yesterday, at the close of my T/E session, a young poet named Sarah showed me the work she had done during our time together. It was ripe and brave, it was unguarded and true, it was tangled up with knowing. It was a conversation I could enter, the salve I desperately needed.

Published on December 18, 2010 02:28

December 17, 2010

Because of them, the world is brighter

Today at T/E Middle School, we thought about the way the world sees us—about what, for example, a cloud floating above might conclude about our mood, about how the changing bloom on a rose would perceive the changing face of a young woman, about how a wind might gather its words to comment on the poor soul caught in its maelstrom. We read from Louise Gluck and Mary Oliver; we asked whether it was possible (Rilke claims it is not) for young hearts to love knowingly or fully.

Today at T/E Middle School, we thought about the way the world sees us—about what, for example, a cloud floating above might conclude about our mood, about how the changing bloom on a rose would perceive the changing face of a young woman, about how a wind might gather its words to comment on the poor soul caught in its maelstrom. We read from Louise Gluck and Mary Oliver; we asked whether it was possible (Rilke claims it is not) for young hearts to love knowingly or fully.It was a truly perfect end to the week, and for the well-preparedness and graciousness of these students, for their willingness to imagine and their courage in presenting their work and ideas, I have Wendy Towle, Marguerite Gordon, and teachers Ms. Nagle and Mr. Boukalik to thank. The world is looking brighter and brighter, the more time I spend with kids.

Published on December 17, 2010 13:14

Let the season begin

My friend Jan Suzanne gathered her girlfriends around her last night and asked them to think about the gifts in their lives, and to think, too, about how they will engage with the world in the year to come.

My friend Jan Suzanne gathered her girlfriends around her last night and asked them to think about the gifts in their lives, and to think, too, about how they will engage with the world in the year to come.I was privileged to be among these women—privileged because just knowing Jan herself is a glory, privileged because one of Jan's beautiful friends allowed me to ride with her to the party (I'd not have managed the city driving myself, given the weaker-by-a-mile self that I've become this week), and privileged because Jan has always drawn about her people powerfully committed to living full and inspired lives.

I have been pounded by the flu this week, and pounded by unremitting work. Jan and her friends ushered in—were emblematic of—the spirit of this season.

Published on December 17, 2010 04:48

December 16, 2010

How Fiction Works/James Wood

In the middle of the night you grab the book that's nearest at hand, while your neighbors' floodlights (yes, they are floodlights) pour into your living room—so star bright that, at three in the morning, you can actually read by the light of them.

In the middle of the night you grab the book that's nearest at hand, while your neighbors' floodlights (yes, they are floodlights) pour into your living room—so star bright that, at three in the morning, you can actually read by the light of them.In any case, the nearest book was How Fiction Works, by James Wood. Am I the last writer alive to read this book? Probably so. But that doesn't dim my enthusiasm for the passages I find here, my sense of discovery. I grow enamored, for example, of declarations such as this:

Novelists should thank Flaubert the way poets thank spring: it all begins with him. There really is a time before Flaubert and a time after him. Flaubert established, for good or ill, what most readers think of as modern realist narration, and his influence is almost too familiar to be visible. We hardly remark of good prose that it favors the telling and brilliant detail; that it privileges a high degree of visual noticing; that it maintains an unsentimental composure and knows how to withdraw, like a good valet, from superfluous commentary; that it judges good and bad neutrally; that it seeks out the truth, even at the cost of repelling us; and that the author's fingerprints on all this are, paradoxically, traceable but not visible. You can find some of this in Defoe or Austen or Balzac, but not all of it until Flaubert.I'm not about to review this book. I'm just going to sit with it, let it stir within me arguments for or against, let it guide me as I set out to write (as I fight to find the time to write) this new novel for adults.

Light on.

Published on December 16, 2010 06:33