Beth Kephart's Blog, page 270

November 29, 2010

The Quickening Maze/Adam Foulds: Reflections

These are among the things required of a reader: Patience. A willing suspension of disbelief. Time. The withholding of judgment (at least for awhile).

These are among the things required of a reader: Patience. A willing suspension of disbelief. Time. The withholding of judgment (at least for awhile).I brought these things to Adam Foulds' The Quickening Maze. I also brought the elevated expectations that I associate with Man Booker Prize finalists, not to mention my interest in insanity and asylums. I felt at home within the very first pages. Foulds' prologue sings; it augurs: He'd been sent out to pick firewood from the forest, sticks and timbers wrenched loose in the storm. Light met him as he stepped outside, the living day met him with its details, the scuffling blackbird that had its nest in their apple tree.

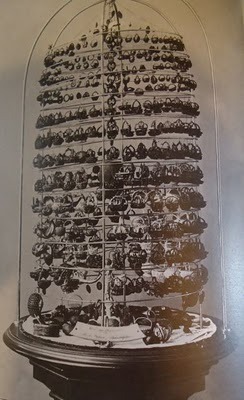

It was after that that I lost and never did quite regain my footing in this historical novel purportedly about John Clare, the nature poet, and his time (1837) at an asylum called High Beach. The story has all the makings of greatness—appearances by the poet Alfred Tennyson (who lives nearby because his melancholic brother has been committed), tangents involving forest-inhabiting gypsies, a population of mentally ill and delusional patients, a lonely teen girl and her too-beautiful friend, the wrongly committed and the wrongly empowered, and a starring role by Matthew Allen, who owns the asylum and dabbles in impossible industrial ventures. Though billed as a novel about John Clare "and his vertiginous fall into madness," we see about as much of him as we do the other members of this sprawling cast, and therein, I think, lies the problem. So much cutting in and out within the confines of a relatively short book diffuses, so that what might have a deeply engaging story—a story of a man losing, finding, losing himself—becomes a puzzle of too-many parts, forcing the reader (this reader) to focus primarily on the mapping of characters as opposed to Clare's internal combustion.

I struggled, in other words, to suspend my disbelief. I struggled to believe in these characters as people. I found myself thinking far more about the mechanics of the novel—about how it had been made, about novelistic choices. With the important exception of the prologue, which is gorgeous, I was also far too aware, all the way through, that I was reading, by which I mean: I kept studying the composition of the sentences, rather than losing myself to their sense or meaning.

I am—of course—in the minority with this, and every book has its right and proper audience. Let me hasten to say, finally, that I will absolutely read another Foulds title, for his talent intrigues, as does his capacity to locate a truly interesting place and time in history.

Published on November 29, 2010 05:22

November 28, 2010

A talent for reading

This is my incredibly beautiful niece, C—queen of the lacrosse fields, a fifth grader taking sixth grade math, a practicing piano student...and a reader. She professes to having read every single Benedict Society (late at night, for hours at a time), is caught up, fast, within the worlds of Rick Riordan, and has now read The Penderwicks four times through. "You buy me the best books," she whispered to me, this Thanksgiving, words that made me happier than I can say—words that sent me straight back out to the bookstores yesterday, looking for the right next things for C's library. There's something that binds readers, isn't it true? And C and I will always have this—these books we love to share.

This is my incredibly beautiful niece, C—queen of the lacrosse fields, a fifth grader taking sixth grade math, a practicing piano student...and a reader. She professes to having read every single Benedict Society (late at night, for hours at a time), is caught up, fast, within the worlds of Rick Riordan, and has now read The Penderwicks four times through. "You buy me the best books," she whispered to me, this Thanksgiving, words that made me happier than I can say—words that sent me straight back out to the bookstores yesterday, looking for the right next things for C's library. There's something that binds readers, isn't it true? And C and I will always have this—these books we love to share.

Published on November 28, 2010 04:25

November 27, 2010

Never Let Me Go/Kazuo Ishiguro: Reflections

I stood in the Orlando airport bookstore at 6 AM, searching for a story. There were the usual suspects—Mennonite in a Little Black Dress, Cutting for Stone, The Art of Racing in the Rain, Half-Broke Horses, Sarah's Key, Little Bee—some of which I've already read, some of which I'll never read, and then there was Never Let Me Go, the Kazuo Ishiguro novel recently made into a feature film. If I knew little about the story, I knew I'd loved Ishiguro's The Remains of the Day, and so I put my fifteen dollars down and made my way toward the gate.

I stood in the Orlando airport bookstore at 6 AM, searching for a story. There were the usual suspects—Mennonite in a Little Black Dress, Cutting for Stone, The Art of Racing in the Rain, Half-Broke Horses, Sarah's Key, Little Bee—some of which I've already read, some of which I'll never read, and then there was Never Let Me Go, the Kazuo Ishiguro novel recently made into a feature film. If I knew little about the story, I knew I'd loved Ishiguro's The Remains of the Day, and so I put my fifteen dollars down and made my way toward the gate.Readers of this blog know that I'm not a fan of a certain kind of science fiction, and for the first several chapters of this book, I found myself in unfamiliar territory, reading of "carers" and "donors" and "completing." My guide to this strange land was a narrator, Kathy, who gets to explaining it all in her good time. She retraces her childhood history in an odd school called Hailsham. She tells us of her best friends, Ruth and Tommy. She withholds, for a time, the worst of the facts animating her life only because those facts are to her mere (or almost mere) matters of fact, and because what interests her is what interests the rest of us: love, friendship, fate, the tiny nearly indiscriminate details that turn a life this way or that. She is calm when she has no right to be. She is human, except, perhaps, she is not. She is bound to a destiny laid out for her by a world that has found a way to cure the big diseases, at a cost she never labels horrific, grotesque, nightmarish, unright. She leaves such judgments to us.

As a narrator, Kathy relies on no flourishes, few metaphors, a paucity of adjectives. She reveals what she remembers in the order that she remembers it, and so that means we read through a maze of clauses that begin, "What happened then was..." or "Before I get to that I should explain..." or "Another thing I noticed was...." Kathy's not a writer. She's a carer. Kathy's not like you and me; why should she dress her story up? If I typically want more from the sentences on the page, I was, by mid-book, perfectly satisfied with Ishiguro's artistic choices and anxious to see the story through.

I finished the book just now, having risen early to complete it. I am left haunted—moved as every human being should be by the prospect of a world in which health (the power of some over the destiny of others) is the awful great divide.

I had, by accident, left The Quickening Maze at home. I'll start on that this afternoon.

Published on November 27, 2010 05:19

November 26, 2010

Our Holiday Greetings

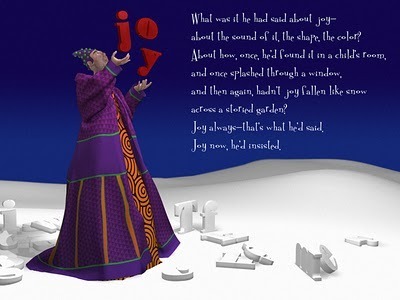

The holidays give me an excuse (and I love having this excuse) to work with my artist-husband on a homemade card, something we've been doing for what seems like a good forever.

The holidays give me an excuse (and I love having this excuse) to work with my artist-husband on a homemade card, something we've been doing for what seems like a good forever.This year, Bill, who has been working with complex software to model and en-robe fantastical figures, decided to create a juggler who, it seemed clear to us, was a master of joy. And so on this One Day Past Thanksgiving, I send his joy (and ours) out to you.

Happy Holidays!

Published on November 26, 2010 09:17

November 25, 2010

Happy Thanksgiving

I have everything to be thankful for today. Two blessings sleep above me while I write. My friends are out there, out here, alive. My garden sleeps; it waits for me. My books are near (new titles, old favorites). I am aware of gifts—physical, felt.

I have everything to be thankful for today. Two blessings sleep above me while I write. My friends are out there, out here, alive. My garden sleeps; it waits for me. My books are near (new titles, old favorites). I am aware of gifts—physical, felt. And the world turns. And the world is.

Happy Thanksgiving.

Published on November 25, 2010 04:00

November 24, 2010

Just Kids/Patti Smith: Reflections

I couldn't stop reading Just Kids, Patti Smith's memoir. I was supposed to be doing other things—was in the land of mouse ears and Grumpy, among writers and teachers, in a hotel nestled around this cloud-reflecting lagoon. But Patti Smith writes poetry, she tells a story, she searches for truth, and Just Kids is so full of the surprising line, the arresting scene. It's full of Patti Smith herself, a rock and roller with a vulnerable heart, a scorcher of a performer who nonetheless craves the sacred companionship of books.

I couldn't stop reading Just Kids, Patti Smith's memoir. I was supposed to be doing other things—was in the land of mouse ears and Grumpy, among writers and teachers, in a hotel nestled around this cloud-reflecting lagoon. But Patti Smith writes poetry, she tells a story, she searches for truth, and Just Kids is so full of the surprising line, the arresting scene. It's full of Patti Smith herself, a rock and roller with a vulnerable heart, a scorcher of a performer who nonetheless craves the sacred companionship of books.Just Kids is advertised primarily as the story of Smith's relationship with Robert Mapplethorpe, and that it is. But it is also the story of Smith's ascension through art—the years she spent choosing between buying a cheap meal and an old imprint, between being an artist or a writer, between being Mapplethorpe's lover and his best friend. She tells us about the conversations that generate ideas among artists and friends, about coincidences that set a life on its path, about the clothes she wore and the mis-impressions she couldn't correct, about a kind of love that is bigger than any definition the world might want to latch onto it. She yields an entire era to us, and though her writing is all sinew, strength, and honesty, she does not once betray her friends, does not invite us to imagine privacies that should remain beyond the veil.

This is, then, a revelation of a book, an exemplar. I could quote from every line. I'll simply give you the beginning:

When I was very young, my mother took me for walks in Humboldt Park, along the edge of the Prairie River. I have vague memories, like impressions on glass plates, of an old boathouse, a circular band shell, an arched stone bridge. The narrows of the river emptied into a wide lagoon and I saw upon its surface a singular miracle. A long curving neck rose from a dress of white plumage.

You don't assess writing like that. You honor it. The National Book Award Nonfiction Panel got this one just right.

Published on November 24, 2010 07:21

November 23, 2010

Priya Ganesan reads Dangerous Neighbors

Among the dozens of emails that floated in during my short time away was one from dear Priya Ganesan, one of two sisters I often write about here. Priya and Maya have been part of my blogging world from the very start, and they are not just bright and important young ladies (writers, readers, academic stars); they are model sisters.

Among the dozens of emails that floated in during my short time away was one from dear Priya Ganesan, one of two sisters I often write about here. Priya and Maya have been part of my blogging world from the very start, and they are not just bright and important young ladies (writers, readers, academic stars); they are model sisters.Thus, when Priya wrote to say that she'd read Dangerous Neighbors, I was eager to hear what she had to say.

I'll let you discover her wonderful words for yourself.

Thank you so much, Priya. These holidays begin with you.

Published on November 23, 2010 12:37

My ALAN moment

I found myself in Orlando at the ALAN convention; I also found co-Egmont USA authors James Lecesne (Virgin Territory) and Tricia Rayburn (Siren). Egmont USA's Katie Halata, who coordinated our days so spectacularly, is snapping this photo. I didn't know what to expect of ALAN; this was my first time there. But what I found were teachers who—mostly on their own dime, taking their own vacation days—had carved out time to learn about new stories and where they come from. There is a powerful commitment to our young out there; I felt the heat and passion of it through the day and over the course of the dinner that Katie hosted—a dinner that included such guests as Matt Skillen, Susan Groenke, Melanie Hundley, Shannon Collins, Steve Bickmore, and incoming ALAN president, Wendy Glenn.

I found myself in Orlando at the ALAN convention; I also found co-Egmont USA authors James Lecesne (Virgin Territory) and Tricia Rayburn (Siren). Egmont USA's Katie Halata, who coordinated our days so spectacularly, is snapping this photo. I didn't know what to expect of ALAN; this was my first time there. But what I found were teachers who—mostly on their own dime, taking their own vacation days—had carved out time to learn about new stories and where they come from. There is a powerful commitment to our young out there; I felt the heat and passion of it through the day and over the course of the dinner that Katie hosted—a dinner that included such guests as Matt Skillen, Susan Groenke, Melanie Hundley, Shannon Collins, Steve Bickmore, and incoming ALAN president, Wendy Glenn.ALAN is a class act. I was proud and happy to be there.

Published on November 23, 2010 08:44

November 21, 2010

Taking Patti Smith and Adam Foulds for a Ride

Because Lilian Nattel is a very brilliant author and reader, I trust her, and when she sang the praises of Adam Foulds' The Quickening Maze back in late June, I knew I'd be reading the book sooner than later. And when the dear and deep and perpetually risk-taking Elizabeth Hand wrote (long before the National Book Award list had been unveiled) that I absolutely had to read Just Kids by Patti Smith (she'd reviewed it for the Washington Post), I said, All right, Liz. I will.

Because Lilian Nattel is a very brilliant author and reader, I trust her, and when she sang the praises of Adam Foulds' The Quickening Maze back in late June, I knew I'd be reading the book sooner than later. And when the dear and deep and perpetually risk-taking Elizabeth Hand wrote (long before the National Book Award list had been unveiled) that I absolutely had to read Just Kids by Patti Smith (she'd reviewed it for the Washington Post), I said, All right, Liz. I will.Yesterday, released for the afternoon from client work, I headed to the Chester County Book & Music Company, which is another version of paradise on earth. We're talking an indie book store here that feels a city block deep, and those who work there stack their favorite reads up and down end shelves. I get lost there, and I don't mind one bit.

This afternoon, I board a plane. Smith's coming with me. So is Foulds.

Published on November 21, 2010 08:38

How to Read the Air/Dinaw Mengestu: Reflections

I have been struggling to find a simple way to recount the deeply quiet, deeply moving nature of Dinaw Mengestu's second novel, How to Read the Air, a novel that feels so searching, so dispelled that it is difficult to remember that it is not, in fact, memoir.

I have been struggling to find a simple way to recount the deeply quiet, deeply moving nature of Dinaw Mengestu's second novel, How to Read the Air, a novel that feels so searching, so dispelled that it is difficult to remember that it is not, in fact, memoir.Air is the story of a young man so scarred by the anguish, anger, and finally submerged violence of his parents—Ethiopian immigrants who did not grow up to become themselves in this land of opportunity—that he lives at terrible remove from himself. Jonas is the name of this unlucky couple's son, and as the novel opens he is newly in love with a lawyer, Angela, whom he will soon marry. In short order (and with Angela's help), Jonas gets a job teaching English at a New York City academy. In similarly short order, the two begin to carve out psychic and spatial distances within their 500 sf basement apartment. There are lies that they do and do not tell one another. There are games played and never won. Jonas is a man who won't be provoked, and often that looks like indifference to Angela, who is desperate to know that she is truly loved. That she is safe inside that love.

Don't all relationships hinge on conversation, of some sort? Don't we expect each other to answer questions, to reflect back, to find some center of perceived truth? Is civility just as cruel as violence, when the civility feels empty, fraudulent?

Jonas is not a bad man. Indeed, he is a character with whom readers can easily empathize, and that is because Mengestu makes us privy to the now and the then of the thoughts in his protagonist's head. We see him sifting his parents' past, looking for clues. We see him leaning on fabrications, assumptions, and possibilities to give himself a sense of place, or having once been placed, inside the tether of a home. If he is able to construct the story of his psychic inheritance for his students, he is not able to deliver that story to his wife, and she requires such binding in. If he is able to know what love is, what it should be, he is unable to act on what he knows:

In our rush to presumably better ourselves we had both missed what had otherwise always been obvious—that it often didn't take much more than careful consideration of each other's needs to secure a degree of happiness.

There is an impeccable quality to Mengestu's prose—a calm, collected rise to despair and violence. He puts a smooth-faced mirror to life—giving us much that we don't know (the plight, let's say, of Ethiopian immigrants) and giving us so much that we can at times know all too well.

Published on November 21, 2010 08:26