Beth Kephart's Blog, page 265

January 5, 2011

I have been writing about

Published on January 05, 2011 02:46

January 4, 2011

Perpetual youth

I always imagined that I would have three children; I had, instead, one entirely remarkable, irreplaceable, love-magic, life-giving boy. And yet my world is still very much about children in the plural—about the kids I've been hanging, traveling, or blogging with over the course of the last 20 years.

I always imagined that I would have three children; I had, instead, one entirely remarkable, irreplaceable, love-magic, life-giving boy. And yet my world is still very much about children in the plural—about the kids I've been hanging, traveling, or blogging with over the course of the last 20 years.Those kids, like all kids, grow up. So that yesterday I heard from Moira, my beloved first student at Penn (and the inspiration for the book, Zenobia), who is now herself a teacher at the University of San Francisco, and, I imagine, a very good one. I heard from one of my favorite young bloggers, so alive with her studies, so complete in her assessment of the world, and generous. I stopped by the blogs of young poet-philosopher-photographer friends, listened to my son read from his screenplay-in-progress, and took note of new books for my niece Claire, who speaks from the palace of her imagination (Aunt Beth, she says, what would you do if you saw ... ). When I'm in danger of being thwarted or unnaturally bent by corporate pressures, I step back into the classroom and teach, and when I think back on this summer's family vacation at the Cayman Islands, I think most of all of the early mornings, when my nephew and I sat side by side on long deck chairs, reading from our respective books.

Disappointments hover; they threaten to unmake us. Curatively, always, there are kids.

Published on January 04, 2011 05:55

January 3, 2011

Already missing time

For seven days it was mine: time. I woke (meaning I slept!), I read, I wrote, I cooked, I took long walks with my son, I watched movies with my husband, I finessed my syllabus for Penn, I saw and talked to friends. It was otherworldly—a strange, delirious slow—and inside that time I came upon an understanding of story that I had not had before, found a way to write a novel that has eluded me for years: one thing at a time, and don't forget the poems, and remember the canal, remember the boy, K, remember the dancer. 16,000 words into this new novel, and I would give anything for another week, or two, of time, another 16,000 words.

For seven days it was mine: time. I woke (meaning I slept!), I read, I wrote, I cooked, I took long walks with my son, I watched movies with my husband, I finessed my syllabus for Penn, I saw and talked to friends. It was otherworldly—a strange, delirious slow—and inside that time I came upon an understanding of story that I had not had before, found a way to write a novel that has eluded me for years: one thing at a time, and don't forget the poems, and remember the canal, remember the boy, K, remember the dancer. 16,000 words into this new novel, and I would give anything for another week, or two, of time, another 16,000 words.But the e-mails come in. Responsibilities.

Published on January 03, 2011 06:51

January 2, 2011

Blue Heart

Published on January 02, 2011 04:47

January 1, 2011

The critics among us

A few weeks ago, as readers of this blog know, I sat down to read James Wood's How Fiction Works and reveled in its elucidations and provocations, its lusty, kinetic, uncompromising language, its call to writerly action:

A few weeks ago, as readers of this blog know, I sat down to read James Wood's How Fiction Works and reveled in its elucidations and provocations, its lusty, kinetic, uncompromising language, its call to writerly action:Realism, seen broadly as truthfulness to the way things are, cannot be mere verisimilitude, cannot be mere lifelikeness, or lifesameness, but what I must call lifeness: life on the page, life brought to different life by the highest artistry.I got the same charge early this morning reading "Why Criticism Matters," the cover story of this weekend's The New York Times Book Review, which yields the floor to literary critics Stephen Burn, Katie Roiphe, Pankaj Mishra, Adam Kirsch, Sam Anderson, and Elif Batuman, all of whom have been invited to report on "what it is they do, why they do it and why it is important." Alas.

There is much value in the whole, much in the way of substance and fine thinking, a little necessary historicism, not too many bricks thrown at the obvious. I am particularly fond, in this sequence of essays, of the emphasis that both Katie Roiphe and Adam Kirsch place on the essential eloquence of the literary critic—on the responsibility the critic bears to write well and meaningfully. Here, for example, is Roiphe:

Now, maybe more than ever, in a cultural desert characterized by the vast, glimmering territory of the Internet, it is important for the critic to write gracefully. If she is going to separate excellent books from those merely posing as excellent, the brilliant from the flashy, the real talent from the hyped — if she is going to ferret out what is lazy and merely fashionable, if she is going to hold writers to the standards they have set for themselves in their best work, if she is going to be the ideal reader and in so doing prove that the ideal reader exists — then the critic has one important function: to write well.Kirsch concludes his essay like this:

By this I mean that critics must strive to write stylishly, to concentrate on the excellent sentence. There is so much noise and screen clutter, there are so many Amazon reviewers and bloggers clamoring for attention, so many opinions and bitter misspelled rages, so much fawning ungrammatical love spewed into the ether, that the role of the true critic is actually quite simple: to write on a different level, to pay attention to the elements of style.

Whether I am writing verse or prose, I try to believe that what matters is not exercising influence or force, but writing well — that is, truthfully and beautifully; and that maybe, if you seek truth and beauty, all the rest will be added unto you.Perhaps I focused most intently on these passages because I keep discovering, at the age I have become, how little good writing is starting to matter to an alarming number of people—to those holding to the notion that grammatical errors (not witty errors, mind you, just plain mistakes) make writing more "hip," to the celebrants of books that are plied with all manner of (unintended) language abuses, to those who declaim against masterful books with sentences riddled by prepositional failures and astonishing noun-verb mismatches. We need standard bearers in times like this, intelligence on the page (and screen), and when I read Wood or Roiphe or Kirsch or the others featured in the Times today, I am elevated. These aren't blustering writers, or showy ones. They are well-read critics with capacious minds who teach not just through the substance of their sentences, but by the very form of them.

I thought of myself as a critic once, writing for Salon.com, Chicago Tribune, Philadelphia Inquirer, Book, so many others. I don't see myself as a critic any longer. I forswear reviews, on this blog, in favor of reflections. I leave the critiquing to the critics.

Published on January 01, 2011 06:33

December 31, 2010

Purge/Sofi Oksanen: Reflections

I end this year privileged with time—time to read and to reflect, time to walk and to spend an afternoon, and then again an evening, with friends.

I take no ounce of time for granted.

This afternoon, in the quiet of my family room, I finished reading Purge, the international bestseller by Sofi Oksanen. It is a story that begins with a fly in an old woman's house—a dirty fly, an invincible fly, a bother. Aliide Truu would like to kill that fly, but soon something more distracting has entered her view—a hump or lump of something crumpled at the foot of the birch outside. Aliide has had plenty to fear in life and she is, by some, despised, and it takes her a long time to decide to investigate that lump. It takes her even longer to decide what to do after she realizes that the lump is a girl—battered, bruised, torn, filthy. A girl at the base of the birch. Her name is Zara. She is, Aliide will learn in time, a victim of the sex-trafficking trade and, more than that, a girl with a tie to Aliide's own sorted and shameful past.

Aliide and Zara, then, are the protagonists of this haunting book—two women whose lives have been defined by politics and treason. Aliide, for her part, is the victim of those wretched forces of oppression that ruled Estonia for much of the 1940s; she is also the victim of her own lust for her sister's husband. Zara is the victim of her own innocence and desire: promised money for a job she did not understand, she took the bait, and suffered. Is there any rescue left in these two women? Can they save each other, or themselves? Working with snatches of stories and letters and reports, Oksanen goes back and forth in time, exposing horrors, incriminating, exculpating, braiding these lives around each other. She is not seeking quiet lyricism on these pages, simple entanglements. Instead, she is pulling back the curtains on a part of the world, and a chapter of history, that I for one knew little of.

Pay attention, Oksanen says. There are women being brutalized by sex trafficking, even today. There are people living with facsimiles of themselves, impossible regrets. There are landscapes terribly unknown to us and wars we haven't studied. Open the book, and read. Taking nothing at all for granted.

Published on December 31, 2010 15:52

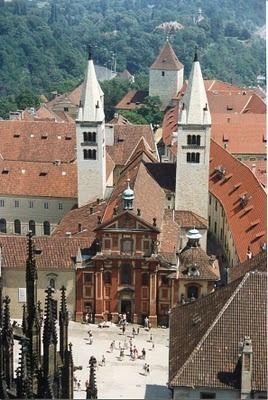

Budejovicka/Beth Kephart Poem

Budejovicka

Budejovicka @font-face {

font-family: "Cambria";

}@font-face {

font-family: "Baskerville Old Face";

}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: "Times New Roman"; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }

@font-face {

font-family: "Cambria";

}@font-face {

font-family: "Baskerville Old Face";

}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: "Times New Roman"; }h3 { margin: 10pt 0in 0.0001pt; page-break-after: avoid; font-size: 12pt; font-family: "Times New Roman"; color: rgb(79, 129, 189); }span.Heading3Char { font-family: Calibri; color: rgb(79, 129, 189); font-weight: bold; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }

It was the way the dust hung, globed and white,and how every room was square and thumbtacked green with ivy. She'd left three slips drying on the line outside, and a peach on the table, and the old bear of her winter coat in the closet because it was still,in some ways, an animal, and, besides, you were onlypassing through and it was summer.You bought a heel of bread at the Metro stop and hunga paper goose from a hook in the ceiling and when you tellthe story (you tell the story)the puppets are alive because of you.

Published on December 31, 2010 06:24

December 30, 2010

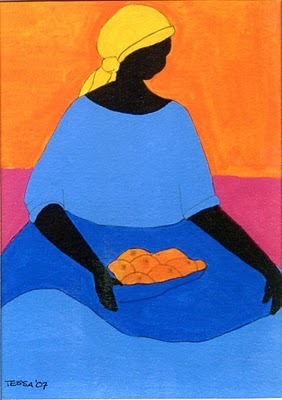

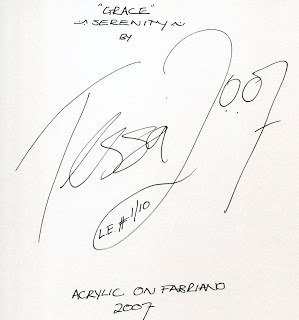

Remembering the Beautiful, the Ever-Bright Tessa Edwards

The blogging world has lost one of its most exquisite voices this week, and I am brokenhearted. Tessa Edwards was a woman who taught us how to love the world and what it means when the world loves you back. She took us, by way of her artful, inimitable blog, to Africa, to the sighting of whales, to the pleasures of a fresh fruit dish, to the children whose health, through the Swazi Project, she so steadfastly supported. She painted art, she cooked it, she wrote it, and when she sent this print of hers to me, by way of London, it was packaged in gold and sealed with gold bees—so gorgeously delivered, so lovingly done up that I did not dare open it for days.

The blogging world has lost one of its most exquisite voices this week, and I am brokenhearted. Tessa Edwards was a woman who taught us how to love the world and what it means when the world loves you back. She took us, by way of her artful, inimitable blog, to Africa, to the sighting of whales, to the pleasures of a fresh fruit dish, to the children whose health, through the Swazi Project, she so steadfastly supported. She painted art, she cooked it, she wrote it, and when she sent this print of hers to me, by way of London, it was packaged in gold and sealed with gold bees—so gorgeously delivered, so lovingly done up that I did not dare open it for days.Tessa fiercely loved her husband and her children, and was never afraid to say so. When she grew ill, she did not complain. She would somehow find a shred of goodness in it—would celebrate the hours she now spent reading, or the travels her daughter took when she could no longer travel herself. We became friends through her blog, but I loved our private conversations, too, the emails she would send explaining a bit more about her life or about her home. Modesty, always, prevailed, as when she wrote, about her beautiful home:

We've been lucky with South Down - it's such a well proportioned house so it's easy to make it look quite pretty. Anyone with a love of colour could do it without blinking...honestly.

A desire to share the world she was privileged to see was all-pervasive, too:

Dearest Beth - Hello! Thank you for your sweet note. I'm very fine thank you, all sun-soaked and brown after our most wonderful trip to Turkey. What a magical place it is - so seeped in history and so astonishingly unspoilt and so utterly beautiful. We'd been to Istanbul before - a truly marvellous city - but had never visited the eastern coast. Far from the madding crowds, it is a place where time has stood still and pastoral life continues as it has done for centuries. I will be writing more about the region and posting photos on my blog in order to share its charm.She made us feel, finally, as if we were there with her, as if we had indeed traversed oceans and miles and found ourselves in the same living room, sitting with a cup of tea. She wasn't virtual to me, ever. She was real and alive, and she will always be. I am posting this, from an email, so that it will always live, and so that you will see how she made all of us more alive, with her:

Dearest Beth -

Oh, I'm almost dumb-struck!

I had just finished catching up on your always fascinating, always thought-provoking, always profoundly luminous blog posts - and reading all the interviews you've had recently when I heard a knock on the door. I got up from my desk, my mind awhirl with images and words from you, and opened the front door to Mr. Postieman. He smiled and chatted about the weather as he handed me my mail which I took from him in dreamy manner, nodding vaguely at his forecast of rain to come.

Scuttling off to the kitchen with the pile of magazines and envelopes and leaflets that he'd given me, I absently flicked through the stack and put it on the table for later perusal. Then I filled the kettle and while waiting for it to boil, I noticed that a white package had slipped out from between two magazines. I picked it up and looked at the postmark. USA. Hmmmm, I wonder......

I opened the seal and drew out a book which I recognised instantly - Ghosts In The Garden! There, on the flyleaf, a message from the author herself to make it even more special, if that were possible. Beth! How will I ever be able to thank you sufficiently for this beautiful, precious gift? Having literally just left your blog, it felt as though you were right there in the room with me - handing the book to me yourself. I'll remember that moment always.

Sweet travels, Tessa. We love you.

Published on December 30, 2010 07:11

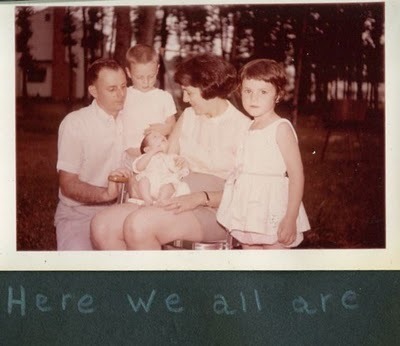

Here we all are: Remembering Lore Kephart

Today is the anniversary of my mother's passing, and in remembering her, I have gone back to old photographs, to this one, in particular, of my mother, father, older brother, younger sister, and me; that is my mother's white pencil caption, below. I return to the words I shared during her memorial service. Lore Kephart passed away four years ago, but she is present, still.

Today is the anniversary of my mother's passing, and in remembering her, I have gone back to old photographs, to this one, in particular, of my mother, father, older brother, younger sister, and me; that is my mother's white pencil caption, below. I return to the words I shared during her memorial service. Lore Kephart passed away four years ago, but she is present, still.@font-face {

font-family: "Times";

}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: "Times New Roman"; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }

On the morning after the evening that my mother passed away, the sky was sherbet colored—bold and also delicate pinks, upward-rising tangerines, traces of lemon. It was the sort of sky one only rarely sees in winter—complex and unforgettable and outrageously beautiful—and it was, of course, my mother, at peace at last. She had brushed by me, on her way to heaven, the night before—the gentlest knock on my right shoulder. She had gathered around her, in her final days, so many varieties of kindness in the doctors and the nurses who had come to care for her, so many reminders that goodness, after such sadness, reigns. She had left behind parts of her to discover still—a note stuck in a bible, a photograph no one remembered taking, the namesake song "Dolores" playing in a nearly empty restaurant. On the day of my mother's funeral, a warm breeze blew. It was her; there is no question. She wouldn't leave us lonely. Beauty is the art my mother mastered. For her, orchids kept their angel wings for surpassing months on end. For her, the mashed potatoes always whipped up right, the gravy thickened, the turkey cut tender to the bone, and anyone who ever had my mother's chocolate-chip cheesecake was never, in some way, the same. She made the dresses my sister and I wore as little girls. She embroidered flowers into our collars. She filled her house with color, fabric, texture, and light. With conversation and surprise. With gifts—abundant, always. In the weeks since my mother's passing, I have been pondering the many measures of a life—that which dissipates, that which remains. I have been looking up, studying the skies. I have been watching the greening of the stalk of curly willow that sits in a vase in my most sun-filled room. I have considered spring's rumbling things, impatient, even in winter, to rise. I have been blessed—immeasurably blessed—by the outreach and wisdom of souls like you, and I have made my decision: Beauty remains. In the words she put down on a page, in the friends she gathered around her, in the gifts only she had the talent to give, in the orchids that yet bloom in her deep-silled windows, and in the man who was her husband and is my father, my mother, always a beauty, remains. Winter will soon cede to spring, and she'll be here. The moon will blaze bright through an afternoon haze, the stars won't leave the sky at dawn, a fox won't run when you walk by, and in all of this, you'll find my mother. And in a garden called Chanticleer, between the risen roots of that most magnificent Katsura tree, there will, come summer, be a stone that reads The Wedge of Sun Between Us. That stone will be my mother's stone. Perhaps she'll find you there.

Published on December 30, 2010 03:27

December 29, 2010

The first time I ever heard Jayne Anne Phillips read, she was here,

Published on December 29, 2010 09:22