Beth Kephart's Blog, page 100

January 16, 2014

Owl in Darkness: Zoe Rosenfeld (Shebooks)

Yesterday I shared the list of books that I'll be reading soon, while waiting, say, for a delayed dishwasher and kitchen countertops to appear (only nine days more, I'm told, or perhaps I did not hear correctly, so famished, thirsty, and wait-weary am I) or while riding the train to the city as my creative nonfiction class gets underway at Penn.

Yesterday I shared the list of books that I'll be reading soon, while waiting, say, for a delayed dishwasher and kitchen countertops to appear (only nine days more, I'm told, or perhaps I did not hear correctly, so famished, thirsty, and wait-weary am I) or while riding the train to the city as my creative nonfiction class gets underway at Penn.This morning, I'd like to tell you about the first book I read from that list, Zoe Rosenfeld's immaculate Owl in Darkness. I did not have the time, last evening, to begin something long and new. And so I turned to this 7,500-word Shebook and fell, at once, in love. Rosenfeld is recreating a writer's retreat—to a manor house, a foreign landscape, a town where she feels she is watched. She cannot write, this writer. She is not sure that living, alone, counts for writerly material. She is afraid of something, haunted by...what? A rabbit, an owl, a giant salamander, an old Edsel in the woods, a minor library, a horse with a wrong name—all these take on mythic proportions.

Writer friends, you will recognize yourself here. Reading friends, you will believe the stillness, the fear. Anyone at all will be elevated by the language. Here is a little of what I found and loved:

In the morning, she watches fog rise out of the trees like pale hair pulled from a brush. The sky is sea-mammal gray overhead, and it hangs low over the forest; the trees look very black, the lichens on their trunks standing out brilliant white and ghostly.You want more? How about this?

At the clearing's edge, there's a strange, sloped shape, and she picks her way toward it through the brush till she can see what it is: an ancient Edsel, doorless, rotting in the woods. As she gets closer, she sees that its interior is almost all gone, the seats reduced to metal coils, the gauges cracked, the floor deep in dead leaves. The car's surface, once blue, is now the bleached, matte color of the sky.Poetry in every line. Real poetry. And a story that can be read at once, experienced in a single sitting.

Published on January 16, 2014 04:04

January 15, 2014

what I'm reading now, or will be reading next, and where you can find me, shortly

Blog readers, I have failed you. I have been absent. I have been mired. Same ole same ole. Life as Beth Kephart.

Blog readers, I have failed you. I have been absent. I have been mired. Same ole same ole. Life as Beth Kephart.Two things, today.

First: The names of the books that I now own and am eager to read and to share:

From the house of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt and the desk of the magnificent Lauren Wein:

The Patron Saint of Ugly, Marie Manilla

For Today I am a Boy, Kim Fu

The Answer to the Riddle is Me: A Memoir of Amnesia, David Stuart MacLean

From a recent trip to a local bookstore:

River of Dust, Virginia Pye

A Tale for the Time Being, Ruth Ozeki

The Flamethrowers, Rachel Kushner

The Invention of Wings, Sue Monk Kid

Elsewhere: A Memoir, Richard Russo

From the debuting memoirists, Jessica Pan and Rachel Kapelke-Dale:

Graduates in Wonderland: True Dispatches from Down the Rabbit Hole

On my iPad

Owl in Darkness, Zoe Rosenfeld (Shebooks!)

Beautiful Ruins, Jess Walters

The Apartment, Greg Baxter (because I could find it in no bookstore!)

Second, I will be at Mid-Winter ALA, which is being held in my very own city this January 24 - January 28 at the Pennsylvania Convention Center, and I'm hoping to see you there. I'll be at the Chronicle Books cocktail party Friday evening, and I'll be signing You Are My Only for Egmont (paperback) Sunday at 3 PM. Please stop by.

I can also be found at the following two events, both at local churches:

February 16, 2014, 11 AM

On the Making of Memoir, a lecture

Bryn Mawr Presbyterian Church,

Bryn Mawr, pA

March 2, 2014, 1:30 - 4:00

Art of Literature/Art of Faith

Handling the Truth Workshop/Memoir Building

Historic Philadelphia in Novels (Dr. Radway and Dangerous Neighbors)

St. David's Church

Devon, PA

Published on January 15, 2014 04:31

January 11, 2014

In the wake of the Jennifer Weiner profile, thoughts on....

It occurs to me, on a nearly minute by minute basis, that I don't know enough. My general sense of geography is poor (until this very morning, for example, I thought Pittsburgh was slightly more north than south within the Pennsylvania borders. Wrong.). Despite having married a Salvadoran man and raised a son who speaks some gorgeous-sounding Spanish, I never learned a second language, save for the rudiments of high school and college French. Don't ask me to add fractions with varying denominators on the fly. Don't ask me, as a contractor did, just yesterday, about the use of the superlative.

It occurs to me, on a nearly minute by minute basis, that I don't know enough. My general sense of geography is poor (until this very morning, for example, I thought Pittsburgh was slightly more north than south within the Pennsylvania borders. Wrong.). Despite having married a Salvadoran man and raised a son who speaks some gorgeous-sounding Spanish, I never learned a second language, save for the rudiments of high school and college French. Don't ask me to add fractions with varying denominators on the fly. Don't ask me, as a contractor did, just yesterday, about the use of the superlative.Hey. You're a writer. You should know this.

Wrong.

Most of the time, don't ask me.

I spend the majority of my life writing very specific reports and stories for highly specialized industries, and that gets me precisely nowhere at a cocktail party. And when I do have time for myself, I'm reading books that many people haven't heard of, books outside the mega-blockbuster mainstream. Otherwise, I'm writing them.

Useless.

But every week I try to make room for the New York Times and at least two articles and all the reviews in The New Yorker. I watch CNN at the gym. I read Philadelphia Inquirer stories. I read local paper headlines while waiting for the train. It may take me many weeks to get caught up, but I try, and yesterday afternoon, after the whole world had already read the 6,800-word Rebecca Mead profile of Jennifer Weiner in The New Yorker, I sat down and discovered it myself. I read it through, with startling speed.

There was so much about the story that I loved—Mead's careful read of Weiner's work, the depictions of my Philadelphia (I may not know much, but I do know how to claim things that aren't actually mine), the courage of Weiner to consistently say what she thinks. Weiner does an excellent job of keeping people talking, debating, engaging. She has far more basic bravery than I do, far more wit, far more savvy, far more style. Further, Mead wrote with intimacy and care. She paid attention. She did not summarily judge. She elucidated. She was both charmed and measured.

So now the buzz is all about the Jennifer Weiner profile in The New Yorker. It's about whether it was deserved, whether her politics are really just self promotion, whether the only way up, in a career, is by climbing over others.

That's not where the story left me; indeed, it left me thinking this: Unless we are highly calculating or infinitely talented, we end up writing what we are capable of writing—what our coagulated talents, experiences, childhoods, internal rhythms lead us to write. I may have once been asked to write a fantasy and tried very very hard (because, Lord, there was money in fantasy), but, baby, my book was another word for disaster. Ask my agent how many times I have tried to write a novel "for adults," and then ask her about the outcome: Too dark. Too static. Un-urgent. I'm not funny, and I could never write funny. I don't shop much, so don't look for brand names in my books. I am really good at parsing the plots on Law and Order SVU, but put me in the dark at the theater with some Tom Clancy film, and I'm the one turning to the good-looking son, saying, Huh? What just happened there?

I write books obsessed with landscapes both exterior and interior because that is who I am, that is what I know, that is the way words congeal in my head, those are the stories I can follow. I seek redemption on the page because I seek it in my own life. My characters are flawed because I sure as hell am. My characters seek, because I discover something that feels true inside that tempo. My stories are historical or scientific or somehow medical or full of old songs, because basically I'm just a good, old researcher at heart.

I write what I can write.

I write it the best I can.

I read the books that, for strange and personal reasons, speak to me.

That's all I'm doing out here.

I suspect it's what most of us are doing. Writing what is in us. Reading what we find we love. Telling the world of our little successes and finds along the way because if we don't talk about it, the work disappears. Our work. Their work. Literature, however you define it.

If we all agree to write the best books we can, if we all agree to set aside presumptive judgments, if we all agree that every novelistic label is in someway a ghetto-ization of the work (YA or crossover, fantasy or fantastical, literary or pink, realistic or comedic), if we all recognize that we are not the only dreaming, hoping writers in the world, maybe literature will become that place where winning never has to occur at the expense of others. Maybe we'll just look at another's very different work and say, Wow. I could never do that. And be grateful that somebody can.

Published on January 11, 2014 07:58

January 10, 2014

Reviewing The Wind Is Not a River by Brian Payton, for Chicago Tribune

A World War II novel that takes place in Alaska? I, too, was surprised when this book arrived for review for Chicago Tribune.

A World War II novel that takes place in Alaska? I, too, was surprised when this book arrived for review for Chicago Tribune.My thoughts on Brian Payton's intriguingly premised new novel are here.

Published on January 10, 2014 11:48

January 9, 2014

Poets and Writers features HANDLING THE TRUTH as a Best Book for Writers

And how grateful I am to Jason Poole for letting me know. Oh, this is good news on a warming but cold day as the sound of a saw buzzes in my house-under-repair background..... Thank you, Poets & Writers, Jason Poole, and, of course, Amy Rennert and Gotham.

And how grateful I am to Jason Poole for letting me know. Oh, this is good news on a warming but cold day as the sound of a saw buzzes in my house-under-repair background..... Thank you, Poets & Writers, Jason Poole, and, of course, Amy Rennert and Gotham.The link is here. Check out the other fine featured books.

Published on January 09, 2014 07:15

January 8, 2014

How do we write atmosphere, and give it tension? What I learned from Eva Figes' Light: With Monet at Giverny

I have Ivy Goodman to thank for Eva Figes. Ivy, a writer I first encountered long ago, when asked to write a review of her collected short stories, A Chapter From Her Upbringing, for the Pennsylvania Gazette. Ivy has been an essential part of my writing and reading life ever since—her reach is wide, her mind is gleaming, she whispers the names of important books into my ear, and often sends something unexpected my way.

I have Ivy Goodman to thank for Eva Figes. Ivy, a writer I first encountered long ago, when asked to write a review of her collected short stories, A Chapter From Her Upbringing, for the Pennsylvania Gazette. Ivy has been an essential part of my writing and reading life ever since—her reach is wide, her mind is gleaming, she whispers the names of important books into my ear, and often sends something unexpected my way.I am grateful for Ivy.

A few weeks ago a slender novel called Light: With Monet at Giverny made its way to me, a gift from Ivy. Its author is Eva Figes, a writer born in Berlin in 1939. Yesterday, while a single carpenter banged away on kitchen cabinets, I stole upstairs, to my son's room, to read. My son has the largest room in this old house. It feels empty with him gone. I'd never sat there before, and read in his chair, but that was the place to be, for oh, my, what a book this is, and absolute quiet is the sound I needed.

Light recounts a single day in the life of Monet, at his estate in Giverny. In the early morning, he rises to paint. Down the hall, his grieving wife does not sleep, and in the house grandchildren stir, and stepdaughters are about, the help, an anxious cook. We will watch Monet in his pursuit of light, in his return to his house, in his lunch hour, in a walk with a friend, in a stroll through shadows with his saddened wife, but we will also come see, thanks to graceful tricks of authorial omniscience, the thoughts and regrets and dreams of the others who have come to Giverny and live through this day.

Little Lily will wonder "for perhaps the thousandth time why the sunlight should be full of dancing motes, gleaming and moving, when the rest of the air seemed quite so empty." Alice, the wife, will "lose all sense of time, as though she had been in a different place, somewhere that belonged to the night and what was left of her night thoughts, where, habitually now, she spoke to those who had only existed in the dark of her own head for years." Marthe, the spinster aunt (and step-daughter to Monet) wonders "what it would be like to do something, anything, from choice." And Jimmy, Lily's brother, will allow a balloon to escape.

But light—on the river, above the shadows, through the slats of window shutters, on the crisp of rose petals, in the wine—is really the protagonist here, and Figes draws it out so spectacularly that I held my breath as I read. This is atmosphere as suspense. This is weather as plot, and I must quote at length from one of many brilliant passages to show you what I mean:

Five o'clock. The top of the willow tree still shone in the green light. The same light was visible on the slope beyond the house, and on the open fields between the railway track and the river. But the water of the lily pond was sunk in the cool shadow, and only the air above it still gleamed fitfully in the slanting light, soft and tenuous as it came through the trees, playful as mist on the substances of shadow below, which it could not disturb. It was as though a tangible split had occurred between sunlight, shadow and substance, and now earth and water were sinking into themselves, taking leave of the sky. Dragonflies and a swarm of midges could still cross the divide, hovering in the air above the depth of shadow, catching the fitful gleam, but the lilies had begun to close up their colours as the water darkened and the sky withdrew from its surface and stood high above the trees.I read Light after reading Donna Tartt's The Goldfinch and Melissa Kwasny's Nine Senses. I read it following review work on two other books. Like Kwasny, Figes reaffirmed for me what it is that I am truly looking for on the page, and what I must learn to do to be the writer I hope someday to be.

Published on January 08, 2014 05:18

January 7, 2014

Nest. Flight. Sky. The cover reveal of my forthcoming Shebooks memoir

In Nest. Flight. Sky: On Love and Loss, One Wing at a Time award-winning memoirist Beth Kephart returns to the form for the first time in years to reckon with the loss of her mother and a slow-growing but soon inescapable obsession with birds and flight. Kephart finds herself drawn to the startle of the winter finch and the quick pulse of hummingbirds and the hungry circling of hawks. She discovers birds in the stories she tells and the novels she writes. She hunts for nests, she waits for song, she learns the stories of bird artists, she waits, again. Nest. Flight. Sky. is about the love that endures and the hope that saves us. It’s about the gift of feathers. Coming shortly, from Shebooks.

In Nest. Flight. Sky: On Love and Loss, One Wing at a Time award-winning memoirist Beth Kephart returns to the form for the first time in years to reckon with the loss of her mother and a slow-growing but soon inescapable obsession with birds and flight. Kephart finds herself drawn to the startle of the winter finch and the quick pulse of hummingbirds and the hungry circling of hawks. She discovers birds in the stories she tells and the novels she writes. She hunts for nests, she waits for song, she learns the stories of bird artists, she waits, again. Nest. Flight. Sky. is about the love that endures and the hope that saves us. It’s about the gift of feathers. Coming shortly, from Shebooks.

Published on January 07, 2014 12:32

Big Handling Hugs to Florinda

I was looking for just the right photograph to thank my dear friend Florinda for her generous citation of Handling the Truth in her Best Books of 2013 list (and her subsequent discussion of the book's impact on her) and then I found this.

I was looking for just the right photograph to thank my dear friend Florinda for her generous citation of Handling the Truth in her Best Books of 2013 list (and her subsequent discussion of the book's impact on her) and then I found this.I took it on a windy day in Boston. I'd escaped into the Museum of Fine Arts, found my way to an exhibition on the color pink, and was standing there all alone.

I had an entire exhibition room all to myself, alone.

I exhaled.

This is similar to what I do when I'm around Florinda, who has been such a dear friend now for a lovely few years, who served as my pronto, we didn't plan it, we loved doing it BEA publicist during the summer of 2011, and who even submitted to this YouTube video with yours truly.

Florinda, I will always be so glad that we connected. And that we remain connected, as readers and writers and friends. Thank you.

Published on January 07, 2014 08:11

January 6, 2014

To review or not to review? Julie Myerson opines, in Mortification

The world is divided into novelists who do and novelists who don't. I don't blame the ones who don't: it's not well paid and it's the quickest way to make enemies this side of the divorce courts. Incest some people call it; others denounce you as a hack. Why, they ask, just because you write books, should you want to review them? But if you write fiction yourself, I'd reply, what could possibly be more satisfying and exciting than the chance to respond in print to the work of your contemporaries? At its best, it's an exhilarating exercise, attempting to explore in words why a novel scorched your heart.

I always do think of it as a response, not a judgment. Part of a feisty, ongoing dialogue—words fired at words. But I know I'm fooling myself. The dialogue can quickly turn to war. So I'm careful. I don't review my friends or authors whose work I already know I don't like. And I start every novel with a sense of hope. But then sometimes, for all your optimism, you just don't like it. And then, yes, you have to say so. But as a novelist myself—who knows how it feels to have your life force sucked out by the crushing power of a bad review—how do I ever justify pulling another author's work apart?

— Julie Myerson in Mortification: Writers' Stories of Their Public Shame

Published on January 06, 2014 06:43

January 5, 2014

this writing thing ain't easy: what I learned in writing a next book

If anyone is under the impression that writing gets easier with each book, I'd beg to differ. The first book is an open book—it has not yet been judged, branded, marketed, categorized. It comes from some pure, unfurnished room in the mind. It belongs, most truly, to you.

If anyone is under the impression that writing gets easier with each book, I'd beg to differ. The first book is an open book—it has not yet been judged, branded, marketed, categorized. It comes from some pure, unfurnished room in the mind. It belongs, most truly, to you.The second book is harder. You have whispers in your ear. You have that stuff that critics said. You have already used some of your favorite images, your most primal memories, and you have expectations now—those that originate within yourself and those that come from external forces. You move on, perhaps. Try a different genre or approach—a book with photographs, a corporate fairytale, a river talking, young adult novels for tweens, young adult novels for teens, young adult novels that you would rather not categorize, a book about the teaching you do. You keep redrawing the maps and raising the ante to somehow get yourself back into that place in which the writing can somehow feel brand new.

Yesterday, I sent Tamra Tuller, my editor, the final draft of a novel that has preoccupied me for eighteen months. I gave myself what seemed at the time to be the right degree of challenge—a foreign but not overly exotic setting, a condition no novelist (to my knowledge) has yet explored, an obsession that strikes at the core of me. I learned, in the making of the book, that I had set myself up for a long, long journey. I could get some parts right at the expense of others. I could be technically correct, but dull. I could deploy some tried and true strategies, but they felt like that—like strategies. I could go all out with a secondary character but miss the boat on the person whose story this was. It was like trying to manage a sine curve. The wrong things rose, the wrong things fell, I couldn't strike the balance.

I could write a book on the writing of this book. I could tell you how much Tamra has meant to me along the way—her truthfulness, her supportiveness, her ability to stop me from giving up on myself. "Think of how proud you will be when you get it right," she said, and I held onto that, through thick and thin, and a lot of the time it was thin.

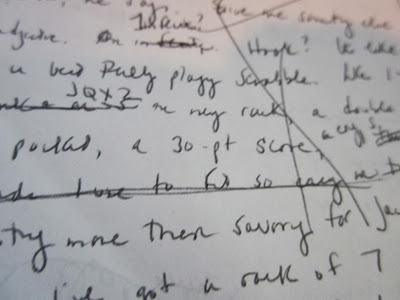

The work I've done over the past few weeks was almost like writing the whole book again, new. Into the substrate of what I had finally figured out as plot and theme I at last worked the intimacy and urgency that all novels, especially those written for young adults, need. Nearly every page of what I had thought, in November, was a near to final draft, ended up looking like that one above. Written over, written over again, crossed out, tossed, begun again.

Oh, I have said to Tamra, and I will say to you: What I have learned, in writing this book. Not to give up, for one thing. Humility, for another.

Published on January 05, 2014 05:25