Beth Kephart's Blog, page 102

December 22, 2013

Christmas 1968. No words necessary.

My grandmother, me, my grandfather, my brother, my mother, my uncle, my sister. My father stands behind the camera.

My grandmother, me, my grandfather, my brother, my mother, my uncle, my sister. My father stands behind the camera.Christmas, 1968.

Published on December 22, 2013 17:12

Looking for meaning (and lights) at Christmas

We find meaning at Christmas when we slow things down, and I had the privilege of doing that this afternoon at my father's house, where we sorted through the past together.

We find meaning at Christmas when we slow things down, and I had the privilege of doing that this afternoon at my father's house, where we sorted through the past together.We found old Santas, fresh candles, a quilt, a rug. We found me, three years old, with Miss Pennsylvania Dairy Queen.

I think I look at the world with the same eyes and the same bitten lips even now.

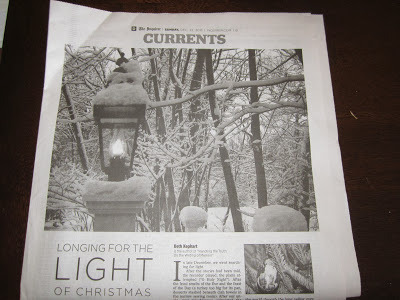

Today the Philadelphia Inquirer ran a piece of Christmas nostalgia—a piece on looking for lights in the season.

I share that here.

Published on December 22, 2013 15:08

December 21, 2013

Ready for Christmas.

Published on December 21, 2013 13:34

in this weekend's Philadelphia Inquirer, the lights of the season

I find enormous pleasure in writing and photographing these monthly pieces for my hometown paper. This weekend I'm remembering family Christmases and the search for light.

I find enormous pleasure in writing and photographing these monthly pieces for my hometown paper. This weekend I'm remembering family Christmases and the search for light.Thank you to Kevin Ferris, who makes these pieces possible.

Published on December 21, 2013 06:17

December 20, 2013

you're doing pretty well, he said ....

We know when we've reached the end of our own capacities. When just a little more is too much. When the need to stretch again becomes the pending snap.

We know when we've reached the end of our own capacities. When just a little more is too much. When the need to stretch again becomes the pending snap.I had already reached the end of the possible within the admittedly not-sufficiently capacious me, when I learned that I would be heading out of town for a one-day business trip. I was to be on a plane by 7 AM and in a new city by 9:30, ready to go, to take notes, to consult, to be a grown-up. Wise. Calm. Helpful. The named day (yesterday) dawned dark and cold.

I hadn't slept.

By 4:45 AM, I was scraping recalcitrant ice from the car; it wouldn't budge; my vision would be periscoped. By 5:00, I was at the gas station, my hands glued to the pump by ice crystals. The gas pump clunked and rattled. No gas flowed. At another icy pump, I began again.

By the time I reached the airport, I found myself in the company of a surprising number of early risers. By the time I got through security, I had to run—all the way through the airport and down to the shuttle bus, which would take me to the F terminal, from which my little plane was scheduled to ascend. I made it in time. I sat down in a slump. I could not find my keys.

You know that rising panic. That dump-everything-out-of-your-bags-and-your-pockets panic. That thing you do in which you mentally retrace every step and begin to imagine terrible things. That was me. The rising panic in the woman who was already gone. The woman who was supposed to be collected, calm, and strong.

I made the calls, I talked to security, I did what could be done. And then I paced up and down the terminal, for the little plane was late. It was then that I saw my friend Julie Diana, a principal dancer of the Pennsylvania Ballet, in an airport display, and just seeing her, just remembering her beauty and her grace, was the thing that calmed me down.

When the tiny plane showed up and we boarded, a kid in a knitted cap sat beside me. An architecture student from Harvard, headed home, he said. We began to talk as the plane filled. I began to move things around. And from who knows which pocket, which hidden place, which silent-during-the-panic cove, those lost keys rained down.

I looked at the student and made some kind of wooting sound. He looked at me and smiled. "I bet you think you're sitting next to a crazy woman," I said.

"You're doing pretty well," he said, "for someone who thought she lost her keys."

Published on December 20, 2013 08:11

December 18, 2013

80 pages into The Goldfinch

True confession: I never read Donna Tartt's The Secret History. I wanted to. I didn't.

True confession: I never read Donna Tartt's The Secret History. I wanted to. I didn't.There. I've done it. Unmasked myself.

But today I find myself 80 pages into Tartt's new novel, The Goldfinch—loved by some, not loved by others, on many lists and shelves. Michael Pakenham, my first book review editor at The Baltimore Sun, taught me this important thing: Have no opinion about a book until you've read it through. Especially have no shared opinion.

So don't expect opinions in this particular blog post. Just take in this paragraph below, a description of a character named Mr. Barbour. It's the first time we meet him.

I can see him. Can you? It's that teleported Continental Congress image that snags my mind's eye.

It was Mr. Barbour who opened the door: first a crack, then all the way. "Morning, morning," he said, stepping back. Mr. Barbour was a tiny bit strange-looking, with something pale and silvery about him, as if his treatments in the Connecticut "ding farm" (as he called it) had rendered him incandescent; his eyes were a queer unstable gray and his hair was pure white, which made him seem older than he was until you noticed that his face was young and pink-boyish, even. His ruddy cheeks and his long, old-fashioned nose, in combination with the prematurely white hair, gave him the amiable look of a lesser founding father, some minor member of the Continental Congress teleported to the twenty-first century. He was wearing what appeared to be yesterday's office clothes: a rumpled dress shirt and expensive-looking suit trousers that looked like had had just grabbed them off the bedroom floor.

Published on December 18, 2013 06:03

December 17, 2013

the great what-if, a writer's privilege

On days when I can stop and think—and today was that sort of gift of a day—I allow my thoughts to drift. I find, inside stories read, stories that haven't yet been written. And I think:

On days when I can stop and think—and today was that sort of gift of a day—I allow my thoughts to drift. I find, inside stories read, stories that haven't yet been written. And I think:Oh, how much fun I would have with that.

There are many parts of writing that I could never live without.

The sudden exhilarating what-if epiphany, before a word has been written, is one such part.

Published on December 17, 2013 13:46

December 16, 2013

On Reading What a Friend Discovers Before You: The Nine Senses/Melissa Kwasny

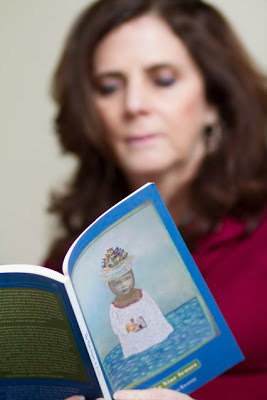

I am a woman blessed with friends more intelligent, more searching, more knowing. Friends who will say—read this. Friends who will place the book in my hands.

I am a woman blessed with friends more intelligent, more searching, more knowing. Friends who will say—read this. Friends who will place the book in my hands.A few days ago Melissa Kwasny's The Nine Senses (Milkweed Editions) arrived with a note from my friend Alyson Hagy. This book, I already knew from the year's correspondence, had left its mark on Alyson. I was eager to read for myself.

And so yesterday and today I read these ingenious, unmediated prose poems. Each line like something almost already gone from here, or gone ahead, and the connections between the lines both sturdy and strange, and the whole unaccountably greater than parts I do not profess to fully understand. Kwasny's thoughts are broken apart and fastened together. Her world is built of flowers, wings, rivers, love, illness, dreams reengineered. Of age reengineered. Love is human. Love is not human. Someone is getting lost. Organs are. Everything is disappearing.

Here: A few lines from "Orient" —

Sometimes it is a matter of one small thing, a gift to send away with a friend. Or to take the morning slow, making calls the way the birds do, to know the others are all safe, in their places. September's sister-quiet, when there is no complaint and you don't speak ill of anyone. Pressed between the days, which are close as reeds. You are used to being in control of your life. You have been lucky is another way of putting this. You try to imagine what it is to think without language. You look at your mother, staggering with her deep heart, or those women who are nine-tenths the needs of others, and you wonder if language has shrunken you. To a body with a foreign language of its own.

Reading a book like The Nine Senses forces a reader like me to slow things down. To watch very carefully, decode. It encourages a writer like me to work with language in a new way. To be unafraid of the strange juxtaposition. To be less inclined to explain.

I know that it is easier to read easy books. I know that it is easier to write them.

I guess I'll always be interested in those on the edge. Those who do it differently—not to show that they can, but because they must.

I am thinking of Alyson Hagy today. And I am forever grateful for her friendship.

(As for the photo: My husband, taking pictures of me yesterday, handed me the book. Let it distract you, he said, for I was grimacing. It distracted me.)

Published on December 16, 2013 16:07

the very right books for the very right people

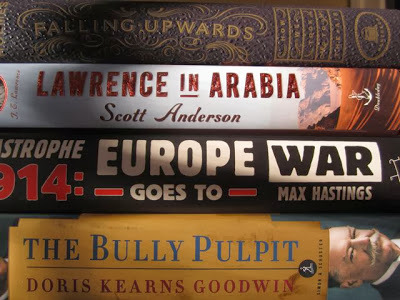

I've just returned from the Wayne Art Center, where I picked up my latest funny pot—just the right size, as it turns out, to collect the holiday cards. My pots are the oddest things in the entire Wayne Art Center world—looking as some child had been given a hunk of clay and the wrong sized paintbrushes. Somehow I don't mind. And besides: the cards matter more.

I've just returned from the Wayne Art Center, where I picked up my latest funny pot—just the right size, as it turns out, to collect the holiday cards. My pots are the oddest things in the entire Wayne Art Center world—looking as some child had been given a hunk of clay and the wrong sized paintbrushes. Somehow I don't mind. And besides: the cards matter more.So there are the cards, and here, in stacks by my feet, are some of the books I've been buying for family and friends this season. I love this. Love buying books with a heightened sense of purpose. It feels like one of the most personal things one can do—finding the very right books for the very right people.

Published on December 16, 2013 12:44

December 15, 2013

Flowers for my Mother, on the Third Sunday in Advent (at Bryn Mawr Presbyterian Church)

Earlier this morning, 5 AM, I was on the phone with my son, who is Los Angeles bound. It's a business trip—a chance to spend some time at the parent company of his media planning firm. It's also a chance for my son to see a city he's never been before—a few hours of not work for the hardworking son who has taken just a half day off in the past nine months of his first out-of-college, it's-for-real job.

Earlier this morning, 5 AM, I was on the phone with my son, who is Los Angeles bound. It's a business trip—a chance to spend some time at the parent company of his media planning firm. It's also a chance for my son to see a city he's never been before—a few hours of not work for the hardworking son who has taken just a half day off in the past nine months of his first out-of-college, it's-for-real job.In time, he set off in the dark for his adventure. I waited for a little more sun, then stepped outside into the crystal palace the world had overnight become to chop the ice away from the car. It's the third Sunday in Advent. I needed to be in church, near Christmas words and Christmas songs. I was married at Bryn Mawr. Our son was baptized there. My mother was beloved there and in her absence my father has become so engaged in the life of this community that I call him The Big Man on the BMPC Campus. He modestly shakes his head. He says, No. But I know. I see. I go to church there with him now, whenever I can. At Bryn Mawr Presbyterian Church my father is equally vital and young. He's necessary, and happy.

Today my father (having gone to the early service) was long gone, on his way to see my brother, when I finally cleared the crystals and got on the road. The ice on the trees and electrical lines kept shattering as I drove—dazzlingly minor key crashes. By the time I opened the door to the sanctuary, the St. Cecelia Girl Choir, St. Andrew Boy Choir, Youth Chorale, and Sanctuary Choir were already bringing Christmas into Christmas. Soon the advent candles were lit, and now Reverend Agnes Norfleet, nearly one year into her job as the pastor of this church—into her bold, bright, life-giving tenure—was giving the kind of sermon that we remember for how it moved us and how it made us laugh as well (she tends to do this). After that the Reverend Nicole Duran webbed together the big and the small of now into an artful prayer, and then there were more songs, another prayer, the postlude. I stood to go.

At the door, Reverend Norfleet gave me one of her welcoming hugs and asked me if I had noticed the flowers. I had. They were full-headed, unusual, white, and many times throughout the service I had studied them, thought how rich and prepossessed they were, how perfectly graceful for Advent.

"They were given by your dad in honor of your mom," she said.

Just like my father, at Christmas.

Published on December 15, 2013 12:16