Beth Kephart's Blog, page 97

February 18, 2014

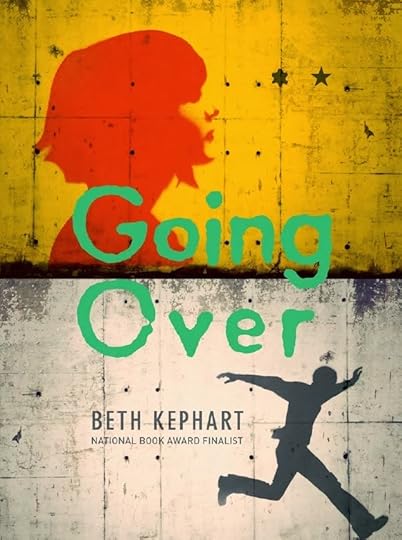

The Starred School Library Journal Review of GOING OVER (phew)

And then we took a break in class (the students heading out to take photographs for an assignment they'll be working on this week). And then, in the quiet room, I checked for messages. And then, there it was, a message from dear Tamra Tuller, who has believed in me and believed in Berlin and believed in Going Over.

And then we took a break in class (the students heading out to take photographs for an assignment they'll be working on this week). And then, in the quiet room, I checked for messages. And then, there it was, a message from dear Tamra Tuller, who has believed in me and believed in Berlin and believed in Going Over.We have another star, she said. This one from School Library Journal.

Few could fully understand how relieved I feel, though Tamra surely does.

Thank you, School Library Journal, for these meaningful words. Thank you for the star.

School Library Journal, starred review

March 1, 2014

Stefan and Ada love each other, but they can only see each other four times a year. That is how often Ada and her grandmother can cross the border into East Berlin to visit the matriarch’s best friend, Stefan’s grandmother. As time passes, Ada obsesses about people who have escaped to freedom, but Stefan worries about those who tried and failed. He spends his days looking through his grandfather’s telescope at the world around him, while Ada spends her nights creating graffiti artwork on her side of the Berlin Wall. While much of this story is focused on the teens and whether they can be together, other characters on both sides of the wall also get their own moments to shine. One of Kephart’s strengths is her ability to immerse readers in 1980s Berlin, a time period that does not receive a lot of attention in most history textbooks. One subplot involves the plight of Turkish immigrants in West Berlin, and Ada becomes involved with trying to save a preschooler in her care from an abusive home. Kephart also uses plenty of sensual language to help readers feel the characters’ aches and pains and to smell the smoke, dill, baked wool, and leather. This is an excellent example of historical fiction focusing on an unusual time period, and the author’s note and selected sources list will be useful for readers who want to learn more about what it was like to live on either side of the Berlin Wall.

Published on February 18, 2014 15:10

Big Apple, Bryn Mawr, Jersey City, Hoboken, Buzz, El Salvador, Berlin: Where I've A-Been Running To

The snow would not defeat me. I've been flying. Through crusty white landscapes and down the slushed streets of the Big Apple (on Friday). Into the quiet calm of Bryn Mawr Presbyterian Church, where I spoke about memories and memoir after Nicole Duran gave her powerful sermon on turning the other cheek. (That is my father, that is me, that is the Reverend Charles Grant, who extended the invitation and introduced me.) Up to Jersey City, then along the Hudson into Hoboken, to spend an evening and then a morning with our son (he showed us where Eli Manning is rumored to live; he showed us where Justin Timberlake recently collected a crowd (my son among them)).

Then a dash back to my home, so that I could interview two corporate clients and then set off running again—to the train station and into my own city and up through the campus of Penn, toward Kelly Writers House, where Buzz Bissinger, one of three 2014 KWH fellows, gave the best reading of his life before both students and friends who have known him for a very long time. Buzz was powerful. He was honest. He was among those who deeply respect his talent and heart. (There is Buzz, above, with the great Rolling Stone writer Sabrina Rubin Erdely, the fabulous famous author/editor Stephen Fried, and myself). After that a meal hosted by Al Filreis (who runs the hugely popular KWH fellows program) and another dash to the station. This time I missed the train, but it didn't matter that much; I had my students' papers with me and plenty to do.

Now I am moments away from heading back down to Penn to greet a classroom full of students whose expectation essays filled me up with joy and wonder. That's what my students—year in and year out—do. I think some angel up there is plucking strings.

In between everything, Serena Agusto-Cox found a book I'd written long ago—my memoir about marriage to a Salvadoran man ( Still Love in Strange Places )—and wrote beautifully of it. Thank you, Serena. Finally, a dear book/life friend wrote to me about Going Over, that Berlin novel due out in a few weeks. She wrote with words that bolstered me.

My red shoes are at the door. I lace them up. I go running.

Published on February 18, 2014 07:32

February 16, 2014

Family Life/Akhil Sharma: Reflections

I arrived early to the ALA Midwinter on (another) snowy Philadelphia day. I was desperate for a copy of Stacey D'Erasmo's Wonderland. I was eager to see what other stories were being ushered into the world. And I hoped to visit the booths of publishing houses that once traveled some of this road with me. I made an early stop at W.W. Norton, therefore—the first house and editor (Alane Mason) who believed in me.

I arrived early to the ALA Midwinter on (another) snowy Philadelphia day. I was desperate for a copy of Stacey D'Erasmo's Wonderland. I was eager to see what other stories were being ushered into the world. And I hoped to visit the booths of publishing houses that once traveled some of this road with me. I made an early stop at W.W. Norton, therefore—the first house and editor (Alane Mason) who believed in me.Among the titles being promoted was Family Life by Akhil Sharma (An Obedient Father), which is fantastically well blurbed by Ann Packer, Gary Shteyngart, Edmund White, and Kiran Desai, and is described this way:

America to the newly immigrated Mishras is everything they could have imagined and more—until tragedy strikes, leaving them lost and shattered. Ajay, the family's younger son, prays to a God he envisions as Superman, longing to find his place amid the ruins of his family's new life. Heart-wrenching and darkly funny, Family Life is a universal story of a boy torn between duty and his own survival.What a surprising novel this is—a terrible story seemingly simply told. Seemingly, I say, for nothing this elemental, this nearly plainspoken, this ultimately elegant is simple. It took this author thirteen years, we learn in an interview with Moshin Hamid, to find a way to translate his own true story into fiction. To somehow tell the story of a promising brother's terrible accident and its impact on a family that had come to Queens from India in search of the better life. The brother must be cared for. The father cannot bear it. The mother has no life but caring. The magical people who come with promises of cures have no impact. Ajay, the younger brother, watches, tries to help, tries not to feel anger, tries not to feel shame, tries somehow to be someone in the midst of everything. He will laugh at the wrong times, pray to everything, pray inconsequentially:

The most important thing was to appeal to God. Each morning, my mother and I prayed before the altar. To me the altar was like a microphone—whatever we said in front of it would be broadcast directly to him. When I did my prayers, I traced an om, a crucifix, a Star of David onto the carpet by pressing against the pile. Beneath these I drew an S inside an upside-down triangle, for Superman. It seemed to me we should flatter anyone who could help.Ajay will study Hemingway, try to write like Hemingway, try to see his life as someone else might see it so that it can be written of. He will try to take solace, but as family falls increasingly apart, solace is sparse. It will not be easy, ever, to trust the slightest trace of happiness.

In his conversation with Hamid, Sharma speaks of why he chose fiction over memoir to tell his story. These words from that interview are telling. Asked what Sharma left out of the story, Sharma says:

The constant despair of living with someone ill, of having no hope. The gravitational pull of that was the most important aspect of my childhood and youth. To describe it truthfully would be to foreground it. Despair is repetitive and dull, however. Not only is it boring but it also kills the reader's interest in the other strands of the narrative.Family Life is, no question, palpably sad. It is a novel quietly told and deeply felt. But breaking through the surface is Ajay himself—ribald at times, funny at others, compassionate, too. He is a boy growing up. Sharma makes us care about his journey.

Published on February 16, 2014 04:23

February 15, 2014

"Cheap Words"—George Packer's New Yorker-sized look at Amazon and the questions it raises for writers

Yesterday, I left the house in the dark and took a nearly-faltered train to Thirtieth Street Station. In truth, the SEPTA train did falter—hitting a tree limb and freezing on the tracks until the brave conductor yanked the tangled arbor from beneath the belly of the car and moved us on.

Yesterday, I left the house in the dark and took a nearly-faltered train to Thirtieth Street Station. In truth, the SEPTA train did falter—hitting a tree limb and freezing on the tracks until the brave conductor yanked the tangled arbor from beneath the belly of the car and moved us on.From there I hopped a train to New York City—entering the Amtrak car through an icy igloo (so much snow inside the train, so truly surreal). I watched the piles of white through the train window. So cold. So high. So slumbering. At Penn Station I disembarked. The cab line was far too long. The streets were clogged. Ill-advised, I know, but still—I started walking toward Wall Street, where my client was awaiting a presentation. There were barricades of snow at most street corners, wide pools of slush above grates, entire sidewalks coated with two or three inches of glassy ice, some streets cordoned off with police tape, thanks to falling icicles. I zigged in and out, over and through, until I was lost, or almost lost. I arrived to my client's building lobby two hours later out of breath—my feet drenched, my black pants mucked, my hair knotted by the wind.

A push of an elevator button, and I ascended. A walk down the hall to the conference room, and I stood at this window, above the Big Apple, and waited for my meeting to begin. I know this company now. I know its leadership team. They have nicknamed me "incorrigible" over the past few weeks. They say it with a smile.

I belong there. I am valued.

I was thinking about my yesterday as I today read "Cheap Words: Amazon is good for customers. But is it good for books?"—the George Packer expose in the February 17/24 The New Yorker. Yes, of course, we've all read the Amazon story. Yes, we have, in one way or the other, participated in its rise or debated its morality. Still, Packer does an extraordinary job of painting the picture of an organization that squeezed its way into our lives, self-perpetuated in mega fashion through acts both feisty-bold and disturbingly secretive, and rapped an entire industry across the knuckles. Amazon has forced readers and writers to choose. It has brought a degree of shame to book buying and publishing that did not exist before. It has ushered in a new era of businesses that are hard to understand, let alone explain.

It seems to me that—if we care about our country, our children, our relationships, our legacy, our intellectual life, our weather-worried planet—we should be able to agree on a few good things. That intelligent and book-smart editors should be able to keep their jobs. That authors who write magnificently but perhaps not for the masses should be able to keep on writing. That readers who want to choose what they read can choose what they read—and read it affordably. Amazon makes many things that were not possible before possible—the longevity of back lists, the existence of Kindle Single operations like Shebooks, the emergence of authors whom "traditional" publishing has overlooked. But it has also helped create, or intensify, a scenario that, well, let Packer explain:

Several editors, agents, and authors told me that the money for serious fiction and nonfiction has eroded dramatically in recent years; advances on mid-list titles—books that are expected to sell modestly but whose quality gives them a strong chance of enduring—have declined by a quarter. These are the kinds of books that particularly benefit from the attention of editors and marketers, and that attract gifted people to publishing, despite the pitiful salaries. Without sufficient advances, many writers will not be able to undertake long, difficult, risky projects. Those who do so anyway will have to expand a lot of effort mastering the art of blowing their own horn.....Seventeen books into my career, I am the opposite of a well-known thing. I am a writer whose writing must be fit into the odd creases of night and early day, a writer who cannot tour because her "real work" beckons, a writer who cares deeply about stories and about language and about heart—a writer who—and you know how grateful I am—has been given opportunities again and again by different publishing houses in different genres—despite the fact that many people see Beth Kephart as that writer who has been generously reviewed but will not sell. I have been lucky. I have been ridiculously lucky, given my record in sales, to keep on sharing my tales.

.... The quest for publishing profits in an economy of scarcity drives the money toward a few big books. So does the gradual disappearance of book reviewers and knowledgeable booksellers, whose enthusiasm might have rescued a book from drowning in obscurity. When consumers are overwhelmed with choices, some experts argue, they all tend to buy the same well-known thing.

But can it continue? Has the time come, after all, to face the facts? Can I honestly expect any publishing house—no matter how generous, no matter how kind—to keep on believing in me in an Amazon and mega-merger world? I read Packer and I wonder how much harder the climb will become, how much more stamina will be required, how much sheer luck will be necessary—not just for me but for so many of my insanely talented writers friends who, like me, keep bumping up against the mid-list wall. I wonder which authors will finally give up or give in, which stories will not get told, which brilliant editors will find some other thing to do, which proud indie might be forced into a lull. I wonder who will rise and who will fall, who will be paraded and who neglected. I wonder about the machinations of it all.

Incorrigible. They call me that in corporate America. Incorrigible. They say it, and we laugh. But I'm going to need a whole lot more incorrigible if I'm to keep writing in the years ahead. I'm going to need it, and so, perhaps, will you.

Published on February 15, 2014 13:06

In the Chicago Tribune: Reviewing Charles Finch and Gina Frangello

Thwarted by winter—as so many of us have been—I have found myself failing and flailing here on the ole blog as well. Here is one post designed to help correct a few recent gaps. Another post, planned for later today, will reflect on a new novel—Family Life by Akhil Sharma (W.W. Norton)—that I picked up at ALA Midwinter after one of the very kind people manning the Norton booth recognized me from my years and books ago with Norton. What an esteemed house that is, and how lucky I was to once be part of the family. Later this week I'll be blogging about The Patron Saint of Ugly, a forthcoming debut by Marie Manilla (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, another wonderful house and former home).

Thwarted by winter—as so many of us have been—I have found myself failing and flailing here on the ole blog as well. Here is one post designed to help correct a few recent gaps. Another post, planned for later today, will reflect on a new novel—Family Life by Akhil Sharma (W.W. Norton)—that I picked up at ALA Midwinter after one of the very kind people manning the Norton booth recognized me from my years and books ago with Norton. What an esteemed house that is, and how lucky I was to once be part of the family. Later this week I'll be blogging about The Patron Saint of Ugly, a forthcoming debut by Marie Manilla (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, another wonderful house and former home). I will catch up. I promise. In the meantime, here are my thoughts on two new books by powerhouse writers: The Last Enchantments by Charles Finch, and A Life in Men by Gina Frangello. Both books have London, England, as a critical backdrop. Both reviews can be found in the pages of the Chicago Tribune. My review of A Life in Men, up this weekend, begins like this:

Love is brutalized throughout Gina Frangello's second novel, "A Life in Men." The pursuit of it, the act, the possibility. Love is what two young American women think they want, are perhaps even owed, but violence — premeditated, haphazard, self-inflicted — intervenes.

One young woman, Nicole (or Nix), will vanish. The other, her best friend, Mary, will live her life trying to collect every experience and many a man before the clock ticks out on her. In Mary's case, the clock is ticking fast: She has cystic fibrosis. Her skin tastes like salt. Her lungs fill with mucous. She survives with the help of all manner of medical paraphernalia. Sometimes it seems that she will not survive at all.

Published on February 15, 2014 06:51

February 13, 2014

Firstborn/Lorie Ann Grover: celebration!

Yesterday I tried to remember my YA book life before Readergirlz entered in, and then I realized—well, I hardly had any YA book life before that happened. Maybe there was a book or two, a blog follower and a smidge, but it was when Readergirlz somehow found me or I, them (I cannot remember the sequence), that I began to live more fully in YA Wonderland.

Yesterday I tried to remember my YA book life before Readergirlz entered in, and then I realized—well, I hardly had any YA book life before that happened. Maybe there was a book or two, a blog follower and a smidge, but it was when Readergirlz somehow found me or I, them (I cannot remember the sequence), that I began to live more fully in YA Wonderland. Lorie Ann Grover, one of the founders of Readergirlz, was there from the start. We shared a love for young readers and a faith that they can be reached, a fascination with dance, and optimism about books—optimism through the thick and the thin, the high and the low of this publishing business. We believed in the intelligence of younger readers—in stretching with them, in learning from them.

I'm very happy, then, to share word today of Lorie Ann Grover's newest book, Firstborn, which was released just this week by Blink. Inspired by an article Lorie Ann read on "the practice of systematic annihilation of baby girls in countries throughout the world," it has been described by early elated reviewers as both a fantasy and a dystopian read. It has a Kirkus star—and people are talking.

I am deeply appreciative of writers who can take me into entirely new worlds, and this is precisely what Firstborn does from its very first page—opens the door to a world we haven't seen before. There are packs bulging with mutton and herbs, a communal rain urn, a priest with black robes and attached wings that hisses to a couple "Your firstborn female is worthless!" For here, in this world, firstborn females are worthless, and the only way for Tiadone, a firstborn girl, to survive is for her parents to raise her as a boy—and hope that she denies, neglects, or somehow otherwise masks her feminine ways.

Her parents choose, for her, this masked survival.

It's a hard life out there, as Tiadone grows up. Here is how Lorie Ann describes her world:

The square overflows with people. Fourteen years after the conquest we R'tan villagers still give a wide berth to the ruling Madronians. Clad in roughspun trousers, ponchos, and layered dresses, R'tan sidestep the Madronians in their ornate robe, and we continue to avert our eyes from their kohl-dotted ones.But it's not just this grittiness that tears at Tiadone's soul. It's her growing sense, as her male initiation rites grow near, that she is suppressing more of her self that any young woman should suppress. That there is something beautiful, indeed, about being female. That having to pretend she is a boy is denying her all that she is coming to love. What are her choices? What are the risks of being exposed? This is the story Lorie Ann, in her loving way, lovingly tells.

We are all rejoicing for you, Lorie Ann. We—Readergirlz Proper and Readergirlz Extended—send our blessings on the powerful new book you are launching into the world.

Published on February 13, 2014 12:43

February 12, 2014

Book sightings (and GOING OVER arrives)

I found these dear-to-me images while I was out and about this week—and then came home to a box I surely did not expect—my box of Going Over.

I found these dear-to-me images while I was out and about this week—and then came home to a box I surely did not expect—my box of Going Over. Work crushes down and a new storm is headed this way. These moments buoy my mood and help the hold back the tides of self-doubt.

Thank you to Penn Bookstore, Chronicle, Philomel, Gotham, and Temple University Press/New City Community Press.

Published on February 12, 2014 11:11

February 11, 2014

Landscaping our prose (Virginia Pye, Vaddey Ratner, Chloe Aridjis)

Today (among so many other things) we're talking about landscape in memoir, about the ways that topography and visual detail elevate and suggest a story. We've read two chapters in Howard Norman's I Hate to Leave This Beautiful Place. We've written responses. And now we'll talk.

Today (among so many other things) we're talking about landscape in memoir, about the ways that topography and visual detail elevate and suggest a story. We've read two chapters in Howard Norman's I Hate to Leave This Beautiful Place. We've written responses. And now we'll talk.I'm going to be sharing these three very different approaches to landscape (each drawn from novels). I now share them with you. What do you learn from them? What do they teach you about possibilities?

First, from the courageous first novel (River of Dust) from the dear Virginia Pye, this evocation of a dusty province in China, 100 years ago:

On springtime mornings like those, when the rain had finally stopped, they waded out toward the creek that had been rising for days. From farms upstream floated all manner of tires, cut logs, old boots, and once a bloated cow, swirling in an eddy until it was skewered by the limbs of a fallen tree.

Now a snatch of London from Asunder, by the amazing Chloe Aridjis:

The dusk of Millbank had filled with the amber lozenges of unoccupied black cabs, miners with lantern-strapped foreheads rushing towards or away from the city centre, as I made my way to meet Daniel at the Drunken Duck, a pub a few streets from Tate Britain.

And now from my friend, Vaddey Ratner—words originating from Cambodia, from the deservedly bestselling In the Shadow of the Banyan:

In the courtyard something stirred. I peered down and saw Old Boy come out to water the gardens. He walked like a shadow; his steps made no sound. He picked up the hose and filled the lotus pond until the water flowed over the rim. He sprayed the gardenias and orchids. He sprinkled the jasmines. He trimmed the torch gingers and gathered their red flame-like blossoms into a bouquet, which he tied with a piece of vine and then set aside, as he continued working. Butterflies of all colors hovered around him as if he were a tree stalk and his straw hat a giant yellow blossom.

Published on February 11, 2014 07:50

Let the (Berlin) wall come down: An Alvin and the Chipmunks Moment

I have Lara Starr to thank for sharing this with me—a surprisingly moving Alvin and the Chipmunks moment that is directly tied to my forthcoming novel, Going Over, about which you can read more here. Lara apparently found this slip of cartoon time by way of a recent review of my book. To that reviewer, if she happens to be wandering this way, thank you.

Published on February 11, 2014 05:06

February 10, 2014

The Meaning of Maggie/Megan Jean Sovern: Reflections

Imagine this: A manuscript arrives on the desks of two exquisite editors at the same time. It is read through at once, loved at once. A tug here, a tug there, and it finds a home at Chronicle Books with Ginee Seo.

Imagine this: A manuscript arrives on the desks of two exquisite editors at the same time. It is read through at once, loved at once. A tug here, a tug there, and it finds a home at Chronicle Books with Ginee Seo.The other exquisite editor is named Tamra Tuller. Soon she will leave one coast to go to another to work at this same fine place called Chronicle. This book—this The Meaning of Maggie by Megan Jean Sovern—is now doubly loved in the same house by two editors who read it early on.

Since I'm lucky enough to know both Ginee and Tamra, I made it a point, not long ago, to snag a copy of this middle-grade novel for myself. What an absolute start-to-finish delight it is. This Maggie is going places—just ask her. She's the future president of the United States. She wins science fairs. She loves education so much that she calls those headed off to summer school the lucky ones and when her mother wants to take Maggie out of school for a special day, Maggie doesn't smile at the thought. She worries about what new knowledge she might miss.

What isn't lucky, though, and what can't easily be explained, is that Maggie's dad isn't well. His legs keep falling asleep. He has had to leave his job. He's supposed to be taking care of things at home while Maggie's mother works the laundry room at the local hotel. But sometimes Maggie's older sisters have to take care of Dad instead. And sometimes there are secrets that everyone refuses to tell. And sometimes things seem to falling apart, even though this eleven-year-old is pretty sure that if you're smart enough you can save the world.

Megan Jean Sovern's Maggie is indefatigable, footnote crazy, and memoir worthy, and this is her story of her quest to find out the name of her dad's condition and to find a way to fix it. It's a charming tale; it's a heartbreaking tale. It's the story of a mom, a dad, and three sisters who—nits and scrambles and sly comebacks aside—want desperately to take care of one another.

The Meaning of Maggie is a book bound for glory. It was one of three books (including Stacey D'Erasmo's brilliant Wonderland and Beth Hoffman's gracious and moving Looking for Me ) that I read throughout the recent storm. Intelligent, beautifully made books are often the best company we have. It's a fact from which I won't be dissuaded.

Published on February 10, 2014 09:31