Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 54

October 28, 2016

THE QUIETEST QUEEN BY GUEST BLOGGER CATHERINE CURZON

A king without an heir is always a matter for concern but a king without so much as a queen is far worse. After all, with no bride, there is not even the faint hope of solving your succession woes. Of course, not having a wife was no bar to having children but they could never take the throne.

One such queenless king was George III, who ascended to the throne on 25 October 1760. George was not without admirers, but the royal marriage bed remained resolutely empty. Just as a list of likely brides was presented at Versailles in 1725 and countless other royal houses throughout the centuries, so Parliament began to think about possible wives for the king. The long list was drawn up, discussed and shown to George, who waved it away. With a sigh, the politicians went back to the drawing board and assembled a second shortlist, no doubt with much fevered mopping of brows.

One of the names on the new list was that of Princess Sophia Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz who was six years younger than George and, crucially, utterly uncontroversial. Her family was respectable if not particularly illustrious and her youth made her the ideal candidate in the eyes of George’s mother, Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, who did not want anyone too remarkable, lest her own influence be usurped.

Intelligent, just pretty enough, and with her only vices apparently a love of snuff and jewels, everyone agreed that Sophia Charlotte might well be the ideal candidate. Charlotte’s widowed mother, Elisabeth, negotiated the match with aplomb, smoothing the road for her daughter’s forthcoming marriage. Sadly, Elisabeth would not live to see Charlotte marry and died in June 1761, just prior to the future queen’s departure for England. Even with her entourage to accompany her, to make a trip to a new land whilst grieving for her mother must have put an enormous strain on the young bride. She maintained her composure admirably but behind her placid exterior, Charlotte mourned her lost mother keenly.

On the rough sea journey Charlotte utterly charmed her escorts whilst in England, George waited for his bride with undisguised enthusiasm, keen to meet the woman who appeared, on paper, to be just what he was looking for. Upon her arrival at St James’s Palace on 8 September 1761, Charlotte threw herself at George’s feet in supplication, head bowed in deference. The king, gentleman that he was, helped his anxious bride to her feet and gently escorted her into the palace to meet his family.

The couple were married by Thomas Secker, Archbishop of Canterbury and from the very beginning, they seemed devoted to one another. This would set the store for the fifty -seven year marriage that was to follow, their love persisting through thick and thin. For George III there were to be no mistresses, official or otherwise; it seemed that, in Charlotte, he had truly found his soul mate.

George presented Charlotte with a diamond ring to be worn alongside her wedding ring; inscribed within the band was Sept 8th 1761. Charlotte appears to have been particularly touched by the ring and wore it from the day of her wedding to the day of her death.

Two weeks after the wedding the king and queen attended their Westminster Abbey coronation. With their shared dislike of being in the limelight, Charlotte and George did not particularly enjoy the ceremony and preferred to spend their time in contented seclusion. Certainly, they were secluded often enough to have fifteen children!

As the years passed and George began to succumb to the mental illness that would later dominate him, Charlotte’s devotion never lessened, She bore the exhausting toll of caring for her husband with fortitude, turning to her unmarried daughters for company, needing someone to show her the affection that her ill husband became increasingly unable to demonstrate.

The king and queen’s marriage ended with Charlotte’s death in 1818 and the king, his sanity gone, never knew that the wife he had once adored was dead, laid to rest in the castle that had become his home and hospital.

Bibliography

Campbell Orr, Clarissa. Queenship in Europe 1660-1815: The Role of the Consort. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.Craig, William Marshall. Memoir of Her Majesty Sophia Charlotte of Mecklenburg Strelitz, Queen of Great Britain. Liverpool: Henry Fisher, 1818.Fraser, Flora. Princesses: The Six Daughters of George III. Edinburgh: A&C Black, 2012.Hadlow, Janice. The Strangest Family: The Private Lives of George III, Queen Charlotte and the Hanoverians. London: William Collins, 2014.Hibbert, Christopher. George III: A Personal History. London: Viking, 1998.Tillyard, Stella. A Royal Affair: George III and his Troublesome Siblings. London: Vintage, 2007.

About the Author

Catherine Curzon is a royal historian and blogs on all matters 18th century at A CoventGarden Gilflurt's Guide to Life. Her work has featured by publications including BBC History Extra, All About History, History of Royals, Explore History and Jane Austen’s Regency World. She has performed at venues including the Royal Pavilion, Brighton, Lichfield Guildhall and Dr Johnson's House. Catherine holds a Master’s degree in Film and when not dodging the furies of the guillotine, she lives in Yorkshire atop a ludicrously steep hill. Follow Catherine on Facebook, Twitter, Google+, Pinterest and Instagram.

Life in the Georgian Court is available now from Amazon UK, Amazon US, Pen & Sword and all good bookshops!

About the Book

As the glittering Hanoverian court gives birth to the British Georgian era, a golden age of royalty dawns in Europe. Houses rise and fall, births, marriages and scandals change the course of history and in France, Revolution stalks the land.

Peep behind the shutters of the opulent court of the doomed Bourbons, the absolutist powerhouse of Romanov Russia and the epoch-defining family whose kings gave their name to the era, the House of Hanover.

Behind the pomp and ceremony were men and women born into worlds of immense privilege, yet beneath the powdered wigs and robes of state were real people living lives of romance, tragedy, intrigue and eccentricity. Take a journey into the private lives of very public figures and learn of arranged marriages that turned to love or hate and scandals that rocked polite society.

Here the former wife of a king spends three decades in lonely captivity, Prinny makes scandalous eyes at the toast of the London stage and Marie Antoinette begins her last, terrible journey through Paris as her son sits alone in a forgotten prison cell.

Life in the Georgian Court is a privileged peek into the glamorous, tragic and iconic courts of the Georgian world, where even a king could take nothing for granted.

Published on October 28, 2016 23:30

October 25, 2016

ONCE AGAIN WEDNESDAY: A MACABRE LOOK AT DEATH MASKS

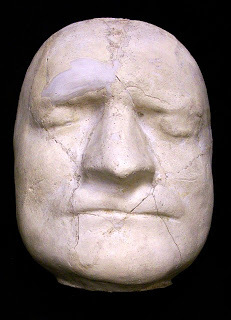

Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli

Sir Issac Newton

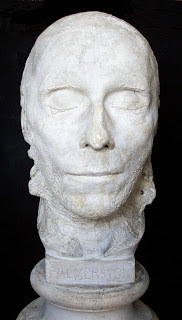

Sir Issac Newton Viscount Henry Palmerston

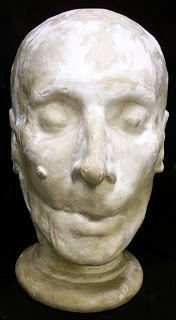

Viscount Henry Palmerston Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley SheridanOriginally published October, 2010

Recently, I came across a book online called The Laurence Hutton Collection of Life and Death Masks: A Pictorial Guide by John Delaney, held in the Manuscripts Division in the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections at Princeton University Library. The making of death masks became popular in the 1800s, but the practice has much older roots. The first masks and effigies made in wax directly from the features of the deceased date from medieval Europe. Personally, I don't get death masks. All of the people from whom death masks were taken were prominent people who had had numerous portraits and busts taken during their lifetimes. Why not remember them thusly, in the prime of their lives, rather than take an image of them in old age - withered, toothless and, more often than not, after having just suffered hours of agony? Perhaps my aversion to death masks is a woman thing. After all, I've yet to come across the death mask of a female.

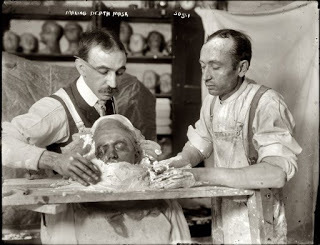

Making a plaster death mask, New York circa 1908, George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress

Making a plaster death mask, New York circa 1908, George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of CongressI'd much rather remember, and hang on my wall, a picture of the Duke of Wellington looking like he does in the banner of this blog rather than like this:

The Duke of Wellington

In a volume titled, "The life of Richard Owen", by Rev. Richard Owen (1894) there is reference to the death mask above in a letter written on November 13, 1852, to Mr. Thomas Poyser, of Wirksworth : " I have been particularly favoured in respect of the remarkable solemnities in honour of the memory of the great Duke. The present amiable inheritor of the title called on me last Wednesday to request that I would call on him to see the cast that had been taken after the Duke's demise, and give some advice to a sculptor who is restoring the features in a bust, intending to show the noble countenance as in the last years of the Duke's life. It is a most extraordinary cast. It appears that the Duke had lost all his teeth, and the natural prominence of the chin and nose much exaggerates the intermediate space caused by the absorption of the alveoli. He of course wore a complete set of artificial teeth when he spoke or ate. My last impression of the living features is a very pleasing one. I brought it away vividly in my mind from Lord Ellesmere's great ball last July."

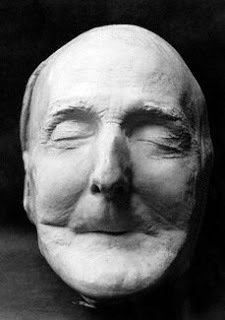

Napoleon's Death Mask

Napoleon's Death MaskOr is it? Is this the face of a short and rather dumpy fifty-one year old man? Napoleon died on May 5th, 1821, on the small island of St. Helena where he had been exiled for life after his shattering defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. A cast for a death mask was made by Dr. Francis Burton within a day and a half of Napoleon's death. But, there was another doctor present at the time of Napoleon’s death, Dr. Antommarchi, who some say was mistakenly credited as the doctor who made the original mold. Immediately after the cast was made, it was stolen. It is believed that a woman named Madame Bertrand, Napoleon’s attendant, took the mold and sailed back to England. Dr. Burton tried but was unsuccessful in getting the cast back. Several years later a death mask turned up and was authenticated as being the original by Dr. Antommarchi, though historians have always argued against it, as the Antommarchi mask looked much too young to have been Napoleon, no to mention that bones of the face are heavier, the face itself longer and proportionally different when compared to the portraits that had been painted of the Emperor Napoleon. It is the official mask currently on display at Les Invalides in Paris, France.

Some believe that the death mask above was actually molded from the living face of the Emperor’s valet, Jean-Baptiste Cipriani.

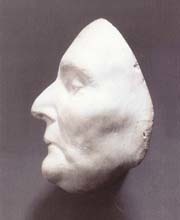

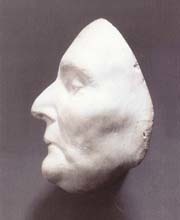

This is the mask that is thought to be authentic:

This death mask was on display at the Royal United Services Institute Museum in London for many years prior to 1973, when the mask was sold. You decide . . . . . here is one of the last portraits of Napoleon, painted by Sir Charles Lock Eastlake on board the ship Bellerophon.

And here is an enlargement of the face

Viola. Ze case it has rested. At least in my mind.

And the strange tales concerning death masks continue - It seems that there was once a special tunnel used to transport the bodies of the hanged from Worcester Gaol to the nearby Royal Infirmary, which stood across the road from the prison and has since been demolished. Until 1832, only criminals' bodies were allowed to be dissected for medical research in the UK. The tunnel was found during work to transfom the former hospital into the new campus for the University of Worcester in the 1950's - as were a number of death masks in the tunnel. These casts had been made to study the characteristics of the criminals' personalities using physiognomy (shape and size of the head) and phrenology (study of the site of different abilities on the head), once thought to be useful in predicting criminal behaviour. The masks are now on display at the George Marshall Medical Museum in Worcester.

Perhaps the strangest story concerning a death mask - and physiognomy - is that involving Gershon Evan, who went on to live another 64 years after his mask was taken. In September 1939, 16 year old Evan was arrested along with 1,000 other young Jewish men and taken to Vienna's Prater Stadium, where all were detained for weeks. Seeking out those with classic "Semitic" features, Nazi scientists — a commission of the anthropology department of the Natural History Museum — selected 440 men for study. Hair samples, fingerprints, hereditary/ biological appraisals and numerous photographs of the men were taken. The length and width of their noses, lips, chins and other facial features were meticulously documented. Evan was one of them. Soon after, Evan was ordered to submit to having a death mask taken.

"My head on the pillow, I stretched out on the table and closed my eyes," he recalled in his memoirs years later. "The man advised me to relax, while he coated my face with a greasy substance. He applied it from the top of my forehead down to the throat and from ear to ear. The lubricant, he explained, was to prevent the hardened plaster of Paris from sticking to my skin." At the end of the procedure, the death mask was removed, catalogued and archived. Evan was given a single cigarette for his troubles before being moved to Buchenwald, from where he was miraculously released four months later. At age 80, Evan was shown his preserved death mask and barely recognised himself in the youthful face held between the hands of a museum curator.

For more on death masks, including instructions on how to make one, visit Carlyn Becchia's Raucous Royals blog.

Published on October 25, 2016 23:00

October 22, 2016

A TOUR GUIDE IN ENGLAND - DAY 6 PART 2: WHAT WE SAW AT CHATSWORTH HOUSE

Published on October 22, 2016 23:00

October 18, 2016

ONCE AGAIN WEDNESDAY: THE DEATH OF NELSON IN LETTERS

Admiral Lord Nelson

Admiral Lord Nelson(29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805)

Marianne Spencer-Stanhope to John Spencer-Stanhope.

November 20th., 1805. Farnely. We begin to be impatient for more news. Think of poor Lady Collingwood—she was in a shop in Newcastle when the Mail arrived covered with ribbands, but the coachman with a black hat-band. He immediately declared the great victory, but that Lord Nelson and all the Admirals* were killed. She immediately fainted. When she heard from Lord Collingwood first he wrote in the greatest -grief for his friend, and said the fleet was in a miserable state. Perhaps that may bring him home.Are you not pleased with his being created a Peer in so handsome a manner. Why has not Lady Nelson some honour conferred upon her? Surely the Widow of our Hero ought not to be so neglected.

Yesterday we drank to the immortal memory of our Hero. Mr Fawkes has got a very fine print of him.* Lord Collingwood was a Vice Admiral in Nelson's fleet.

Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood

Vice Admiral Cuthbert CollingwoodA Letter from Mrs. Fitzherbert to Mrs. Creevey.

"Nov. 6, 1805."Dr. Madam,

"The Prince has this moment recd, an account from the Admiralty of the death of poor Lord Nelson, which has affected him most extremely. I think you may wish to know the news, which, upon any other occasion might be called a glorious victory—twenty out of three and thirty of the enemy's fleet being entirely destroyed—no English ship being taken or sunk—Capts. Duff and Cook both kill'd, and the French Adl. Villeneuve taken prisoner. Poor Lord Nelson recd, his death by a shot of a musket from the enemy's ship upon his shoulder, and expir'd two hours after, but not till the ship struck and afterwards sunk, which he had the consolation of hearing, as well as his compleat victory, before he died. Excuse this hurried scrawl: I am so nervous I scarce can hold my pen. God bless you.

The Prince of Wales, afterwards King George IV

The Prince of Wales, afterwards King George IVCorrespondence from Mrs. Creevey to Mr. Creevey.

"Nov. 7, 1805.

". . . [The Prince's] sorrow [for Nelson's death] might help to prevent his coming to dinner at the Pavillion or to Johnstone's ball. He did neither, but stayed with Mrs. Fitz; and you may imagine the disappointment of the Johnstones. The girl grin'd it off with the captain, but Johnstone had a face of perfect horror all night, and I think he was very near insane. I once lamented Lord Nelson to him, and he said:— 'Oh shocking: and to come at such an unlucky time!' . . ."

Emma, Lady Hamilton

Emma, Lady Hamilton"8th Nov.

". . . The first of my visits this morning was to 'my Mistress' (Mrs. Fitzherbert) ... I found her alone, and she was excellent—gave me an account of the Prince's grief about Lord N., and then entered into the domestic failings of the latter in a way infinitely creditable to her, and skilful too. She was all for Lady Nelson and against Lady Hamilton, who, she said (hero as he was) overpower'd him and took possession of him quite by force. But she ended in a natural, good way, by saying:—' Poor creature! I am sorry for her now, for I suppose she is in grief.'"

"Dec. 5,1805.

". . . It was a large party at the Pavillion last night, and the Prince was not well . . . and went off to bed. . . . Lord Hutchinson was my chief flirt for the evening, but before Prinny went off he took a seat by me to tell me all this bad news had made him bilious and that he was further overset yesterday by seeing the ship with Lord Nelson's body on board. . . ."

From an undated letter written by Vice Admiral Collingwood to Edward Collingwood - My dear friend received his mortal wound about the middle of the fight, and sent an officer to tell me that he should see me no more. His loss was the greatest grief to me. There is nothing like him for gallantry and conduct in battle. It was not a foolish passion for fighting, for he was the most gentle of human creatures, and often lamented the cruel necessity of it; but it was a principle of duty, which all men owed their country in defence of their laws and liberty. He valued his life only as it enabled him to do good, and would not preserve it by any act he thought unworthy. He wore four stars upon his breast and could not be prevailed to put on a plain coat, scorning what he thought a shabby precaution: but that perhaps cost him his life, for his dress made him the general mark.

He is gone, and I shall lament him as long as I live.

Originally published October 21, 2011

Published on October 18, 2016 23:30

October 14, 2016

A TOUR GUIDE IN ENGLAND: DAY 6 - PART ONE - EDENSOR

As Diane and I had walked to Chatsworth House from Baslow yesterday and approached the House from the stable side, we wanted to approach the House from the bridge today, so that it would suddenly come into view - magically, enchantingly, stunningly into view. In all its centuries old glory. This meant that we needed to begin our day in Edensor, the picturesque model village built to the specifications of the 6th Duke of Devonshire with the help of Joseph Paxton. The entire village was moved over the hill from it's original location just by the River Derwent, thus freeing up the view and leaving it idyllic as seen from the House. It is said that after quickly looking through designs for the new house, the Duke could not make up his mind and chose all the different styles in the book. The result is that Edensor is a charming mix of designs ranging from Norman to Jacobean, Swiss-style to Italian villas. A few of the old houses remained virtually untouched including parts of the old vicarage, two cottages overlooking the green, the old farmhouse which now houses the post office, shop and tea rooms, as well as the Gardener’s Cottage across the road.

After a look round the picturesque village, Diane and I headed to the Edensor's St. Peter’s Church and it’s cemetery where Kathleen Kennedy Cavendish and Deborah Mitford Cavendish rest. Kathleen "Kick" Kennedy was the daughter of Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr. and Rose Kennedy, sister of future U.S. President John F. Kennedy, and wife of William Cavendish, Marquess of Hartington, heir apparent to the Duke of Devonshire. They married in May 1944 and, sadly, he was killed on active service, only a few weeks later. Kathleen died in a plane crash in 1948, flying to the South of France on holiday with her new fiancé Peter Wentworth-Fitzwilliam, 8th Earl Fitzwilliam. The Cavendish family considered Kick one of their own and had her buried at St. Peter's in the family plot. I very much wanted to see Debo and Kick's graves, as apparently did others, as we found this sign near the church door, which proved exceedingly helpful.

Edensor has a unique and charming way of keeping the graveyard tidy.

Before we left Edensor, there was time for another, more leisurely stop at the Tea Cottage.

One last look over a fence and we headed for Chatsworth House, just a mile away.

Would you like to see Edensor for yourself? We'll be given a private, guided tour of the village during Number One London Tours 2017 Country House Tour. Keep watching this space for more details, itinerary, pricing and reservations.

Part Two Coming Soon!

Published on October 14, 2016 23:00

October 11, 2016

ONCE AGAIN WEDNESDAY: THE DEATH OF MISS CHOLMONDELEY

The town of Leatherhead, two miles south of Ashsted, was an ancient market town in Surrey, the market having long been discontinued by the early nineteenth century. The town still held a fair on Lady's Day, three weeks before Michaelmas, during the Regency period, "but otherwise the town possessed no trade or privilege than what its being a great thoroughfare produces.” The only "remarkables" were the fourteenth-century church and the bridge, which was a very neat structure over the River Mole, built of brick and consisting of fourteen arches.

The town of Leatherhead, two miles south of Ashsted, was an ancient market town in Surrey, the market having long been discontinued by the early nineteenth century. The town still held a fair on Lady's Day, three weeks before Michaelmas, during the Regency period, "but otherwise the town possessed no trade or privilege than what its being a great thoroughfare produces.” The only "remarkables" were the fourteenth-century church and the bridge, which was a very neat structure over the River Mole, built of brick and consisting of fourteen arches. At this quite and idyllic a spot, however, there occurred a Regency tragedy in 1806 – a coaching accident involving the Princess of Wales. Dr. Hughson described the incident thusly in his Description of London:

"A most dreadful accident occurred in this town in the year 1806. Her royal highness the Princess of Wales, on the afternoon of October 2, was on her way in a barouche, attended by Lady Sheffield and Miss Harriet Mary Cholmondeley, to pay a visit to Mrs. Lock, at Norbury Park (right), and was driven by the princess's own servants as far as Sutton. At this place post-horses were put to the carriage, driven by the post-boys belonging to the Cock Inn; her highnesses horses remained at Sutton till she returned. On her arrival at Leatherhead, the carriage, which was drawn by four horses, whilst turning around an acute angle of the road, was overturned. It appears that the drivers, through extreme caution, had taken too great a sweep in turning the corner, which brought the barouche on a rising ground, by which it was overset; but before its fall it swung about a great tree.

"A most dreadful accident occurred in this town in the year 1806. Her royal highness the Princess of Wales, on the afternoon of October 2, was on her way in a barouche, attended by Lady Sheffield and Miss Harriet Mary Cholmondeley, to pay a visit to Mrs. Lock, at Norbury Park (right), and was driven by the princess's own servants as far as Sutton. At this place post-horses were put to the carriage, driven by the post-boys belonging to the Cock Inn; her highnesses horses remained at Sutton till she returned. On her arrival at Leatherhead, the carriage, which was drawn by four horses, whilst turning around an acute angle of the road, was overturned. It appears that the drivers, through extreme caution, had taken too great a sweep in turning the corner, which brought the barouche on a rising ground, by which it was overset; but before its fall it swung about a great tree."The dreadful consequence was, that Miss Cholmondeley was killed on the spot; providentially the princess received no other injury, except a cut on her nose, and a bruise on her arm. Lady Sheffield did not receive the slightest hurt, besides that which overwhelmed the royal party, by the shocking accident. Her royal highness returned to Blackheath the next day."

The Annual Register expands on the incident:

It is with great concern we have to state the following melancholy accident. Her royal highness the Princess of Wales was this afternoon on her way to the seat of Mr. Locke, at Norbury Park, near Leatherhead, Surrey, in a barouche, attended by Lady Sheffield and Miss Harriet Mary Cholmondeley, and was driven by her royal highness's own servants. They took post horses, and were driven by the post-boys belonging to the Cock Inn. Her royal highnesses horses and servants were left to refresh in order to take her home that evening. Her royal highness proceeded to Leatherhead, when on turning a sharp corner to get into the road which leads to Norbury Park, the carriage was overturned, opposite to a large tree, against which Miss Cholmondeley was thrown with such violence, as to be killed on the spot. She was sitting on the front seat of the barouche alone. Her royal highness and Lady Sheffield occupied the back seat, and were thrown out together. They went into the Swan Inn, at Leatherhead. Sir Lucas Pepys, who lives in that neighbourhood, and had not left Leatherhead (where he had been to visit a patient) more than a quarter of an hour, was immediately followed, and brought back; and a servant was sent to Mr. Locke's, with an account of the accident. Mrs. L. arrived in her carriage with all expedition, and conducted the princess to Norbury Park, where Sir Lucas Pepys attended her royal highness and, as no surgeon was at hand, bled her himself. On the following day the princess returned to Blackheath. Her royal highness received no other injury than a slight cut on her nose, and a bruise on one of her arms. Lady Sheffield (wife of Lord Sheffield, who was with her, did not receive the slightest injury. — An inquest was held on the 4th, before C. Jemmet, esq. coroner for Surrey, on the body of Miss Cholmondeley, at the Swan Inn, Leatherhead. It appeared, by the evidence of a Mr. Jarrat at Leatherhead, and of an hostler belonging to the inn, that the princess's carriage, drawn by four horses, with two postillions, while turning round a very acute angle of the road, was overturned. The drivers, through extreme caution, had taken too great a sweep in turning) the corner, which brought the carriage on the rising ground, and occasioned its being upset. The carriage swung round a great tree before it fell. When the surgeon saw the Princess of Wales, she most benevolently desired him to go up stairs, as there was a lady who stood more in need of his assistance. The surgeon (Mr. Lawden, of Great Bookham) then went to Miss Cholmondeley, and found her totally deprived of life. There was a violent contusion on her left temple; and her death appeared to have been occasioned by the rupture of a blood vessel. The jury returned a verdict of Accidental Death. Miss Cholmondeley was born in 1753, and was the daughter of the late lion, and Rev. Robert Cholmondeluy, rector of Hartingford-Bury, and St. Andrews, Hertford, who was son of the third earl of Cholmondeley, and uncle to the present earl. Her mother is living, and resides in Jermyn-street. On the 8th, at 12 o'clock, the remains of this unfortunate lady were interred in Leatherhead church, close to the spot where lady Thompson, wife of sir John Thompson, some years since lord mayor of London, is buried. The body was, on the evening of the sixth, removed from the Swan Inn to an undertaker's near the church-yard, and was followed to the grave by her brother, George Cholmondcley, esq. one of the Commissioners of excise; the hon. Augustus Phipps ; William Locke, esq ; S. Gray, esq. and several other gentlemen. The fatal spot where this amiable lady met her sudden death is still visited by crowds.

It may be noted that the Locke's were also close friends of famed diarist and novelist Frances Burney, Mme d'Arblay who mentions the family often in her journal, as seen by the entries here for 1784. At this period the health of Mrs. Phillips (Fanny's sister Susan) failed so much that, after some deliberation, she and Captain Phillips decided on removing to Boulogne for change of air. The anxiety evidenced in the letter below was due to Burney's waiting to here of her sister's safe arrival in France.

It may be noted that the Locke's were also close friends of famed diarist and novelist Frances Burney, Mme d'Arblay who mentions the family often in her journal, as seen by the entries here for 1784. At this period the health of Mrs. Phillips (Fanny's sister Susan) failed so much that, after some deliberation, she and Captain Phillips decided on removing to Boulogne for change of air. The anxiety evidenced in the letter below was due to Burney's waiting to here of her sister's safe arrival in France.Friday, Oct. 8th.—I set off with my dear father for Chesington, where we passed five days very comfortably; my father was all good humour, all himself,— such as you and I mean by that word. The next day we had the blessing of your Dover letter, and on Thursday, Oct. 14, I arrived at dear Norbury Park at about seven o'clock, after a pleasant ride in the dark. Mr. Lock most kindly and cordially welcomed me; he came out upon the steps to receive me, and his beloved Fredy waited for me in the vestibule. Oh, with what tenderness did she take me to her bosom! I felt melted with her kindness, but I could not express a joy like hers, for my heart was very full—full of my dearest Susan, whose image seemed before me upon the spot where we had so lately been together. They told me that Madame de la Fite, her daughter, and Mr. Hinde, were in the house; but as I am now, I hope, come for a long time, I did not vex at hearing this. Their first inquiries were if I had not heard from Boulogne.

Saturday.—I fully expected a letter, but none came; but Sunday I depended upon one. The post, however, did not arrive before we went to church. Madame de la Fite, seeing my sorrowful looks, good naturedly asked Mrs. Lock what could be set about to divert a little la pauvre Mademoiselle Burney ? and proposed reading a drama of Madame de Genlis. I approved it much, preferring it greatly to conversation; and, accordingly, she and her daughter, each taking characters to themselves, read "La Rosiere de Salency." It is a very interesting and touchingly simple little drama. . . . Next morning I went up stairs as usual, to treat myself with a solo of impatience for the post, and at about twelve o'clock I heard Mrs. Locke stepping along the passage. I was sure of good news, for I knew, if there was bad, poor Mr. Locke would have brought it. She came in, with three letters in her hand, and three thousand dimples in her cheeks and chin! Oh, my dear Susy, what a sight to me was your hand! I hardly cared for the letter; I hardly desired to open it; the direction alone almost satisfied me sufficiently. How did Mrs. Locke embrace me! I half kissed her to death. Then came dear Mr. Locke, his eyes brighter than ever— "Well, how does she do?"

This question forced me to open my letter; all was just as I could wish, except that I regretted the having written the day before such a lamentation. I was so congratulated! I shook hands with Mr. Locke; the two dear little girls came jumping to wish me joy; and Mrs. Locke ordered a fiddler, that they might have a dance in the evening, which had been promised them from the time of Mademoiselle de la Fite's arrival, but postponed from day to day, by general desire, on account of my uneasiness.

Published on October 11, 2016 23:00

October 7, 2016

A TOUR GUIDE IN ENGLAND: DAY 5 - PART TWO: A WALK TO CHATSWORTH

After poking around Baslow for a bit, Diane and I realized that we still had a chunk of time left to us before it was time for dinner. We were both eager to see Chatsworth again and so we quickly decided what better way to spend a few hours than by walking over hill and dale for a glimpse of the House.

There were many unique and inventive gates to be got through on our way.

The Cannon Kissing Gate, above and below.

Our walk ended at Edensor, above, where we through our tired selves upon the mercy of the counter girl at the tea shop, which was just closing, and asked her to call us a cab back to the Cavendish Arms. We had seen Chatsworth, and the walk was lovely, but very much longer than we'd supposed!

Next stop Edensor - coming soon!

There were many unique and inventive gates to be got through on our way.

The Cannon Kissing Gate, above and below.

Our walk ended at Edensor, above, where we through our tired selves upon the mercy of the counter girl at the tea shop, which was just closing, and asked her to call us a cab back to the Cavendish Arms. We had seen Chatsworth, and the walk was lovely, but very much longer than we'd supposed!

Next stop Edensor - coming soon!

Published on October 07, 2016 23:00

October 5, 2016

GUEST POST BY AUTHOR ABIGAIL DANE, PART THREEFrom Victori...

GUEST POST BY AUTHOR ABIGAIL DANE, PART THREEFrom Victoria: Abigail Dane presents her third essay, based on research for her trilogy The Whitleigh Series. The Pirate and the Virgin, Book One, is now available. Book two, The Baron and the Lady, will be published soon. Many thanks, Abigail!

Battle of Worcester and its AftermathPart 3 of 3

For six weeks, Charles II—“England’s Most Wanted,” if you will—survived many harrowing narrow escapes and near misses before his ultimate safe arrival in France. If those perilous weeks provided the catalyst for the fugitive king’s future frivolity, as some posit, they also exposed him to the ordinary lives of ordinary people in a way most kings would never experience. His turns as servant, tenant farmer, kitchen helper, debt collector and more may help to explain why Charles II was later referred to as “a king without airs and graces.” After Oliver Cromwell’s death on 3 September 1658—seven years to the day after the Battle of Worcester—his incompetent son, Richard, became Lord Protector in his stead. Richard’s succession—or usurpation, as it was widely considered—lasted only nine months before he was forced to abdicate in 1659. He was allowed to “fade away” into obscurity but was thereafter referred to, ignominiously, as “Tumbledown Dick.”

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

By 1660, the vacuum left by the departure of the infamous Cromwells would be filled by none other than the fugitive king himself. Arriving in London on his 30thbirthday and having survived to gain the ultimate victory, Charles reclaimed his father’s throne and reestablished the British monarchy during a period that came to be called “The Restoration,” which restored not only the king and monarchy, but England’s pursuit of pleasure and gaiety, as well. If Cromwell is best remembered for his severe, joyless Puritanism, Charles II—affectionately called “the Merry Monarch”—is best remembered for his many mistresses and his many illegitimate children by them.

Charles II

Charles II

With the reign of Charles II, the pendulum would swing its full arc from piety to hedonism—as if the last nine years, with their terrible cost, turmoil, misery and death, had never happened. By the time of Charles’ death in 1685, he had many children but no legitimate heirs, so he was succeeded by his brother James, who reigned as James II. One can only wonder what Cromwell would have thought of his legacy if he had returned to see what had become of his great cause in such a brief time.

POSTSCRIPT: Though the English Civil War ended in Worcester in September 1651, one might say the curtain did not descend on the last act of the play until June 2008. That’s when another Charles, also the Prince of Wales, paid off the debt incurred by his ancestor and namesake 357 years earlier. It seems Charles II had contracted for the Worcester Clothiers Company to provide uniforms to outfit his army, but in his haste, skipped town without paying the £453.3s he owed. With interest, that debt in 2008 would have been £47,500.

Source: “Historical Notes: Battle of Worcester and its Aftermath,” in The Baron and the Lady, book two in the “Whitleigh series” by Abigail Dane. http://TransitionsUnlimited.biz, AbigailDaneRomance@gmail.org.

Abigail Dane

Abigail Dane

Resources: Atkinson, Charles Francis (1911) "Great Rebellion#The Third Scottish Invasion of England" in Chisholm, Hugh Encyclopædia Britannica12 (11th ed.) Cambridge University Press pp. 420–421. Also, some background info and images are from the Military Wiki (http://military.wikia.com/wiki/Battle_of_Worcester)

Battle of Worcester and its AftermathPart 3 of 3

For six weeks, Charles II—“England’s Most Wanted,” if you will—survived many harrowing narrow escapes and near misses before his ultimate safe arrival in France. If those perilous weeks provided the catalyst for the fugitive king’s future frivolity, as some posit, they also exposed him to the ordinary lives of ordinary people in a way most kings would never experience. His turns as servant, tenant farmer, kitchen helper, debt collector and more may help to explain why Charles II was later referred to as “a king without airs and graces.” After Oliver Cromwell’s death on 3 September 1658—seven years to the day after the Battle of Worcester—his incompetent son, Richard, became Lord Protector in his stead. Richard’s succession—or usurpation, as it was widely considered—lasted only nine months before he was forced to abdicate in 1659. He was allowed to “fade away” into obscurity but was thereafter referred to, ignominiously, as “Tumbledown Dick.”

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver CromwellBy 1660, the vacuum left by the departure of the infamous Cromwells would be filled by none other than the fugitive king himself. Arriving in London on his 30thbirthday and having survived to gain the ultimate victory, Charles reclaimed his father’s throne and reestablished the British monarchy during a period that came to be called “The Restoration,” which restored not only the king and monarchy, but England’s pursuit of pleasure and gaiety, as well. If Cromwell is best remembered for his severe, joyless Puritanism, Charles II—affectionately called “the Merry Monarch”—is best remembered for his many mistresses and his many illegitimate children by them.

Charles II

Charles IIWith the reign of Charles II, the pendulum would swing its full arc from piety to hedonism—as if the last nine years, with their terrible cost, turmoil, misery and death, had never happened. By the time of Charles’ death in 1685, he had many children but no legitimate heirs, so he was succeeded by his brother James, who reigned as James II. One can only wonder what Cromwell would have thought of his legacy if he had returned to see what had become of his great cause in such a brief time.

POSTSCRIPT: Though the English Civil War ended in Worcester in September 1651, one might say the curtain did not descend on the last act of the play until June 2008. That’s when another Charles, also the Prince of Wales, paid off the debt incurred by his ancestor and namesake 357 years earlier. It seems Charles II had contracted for the Worcester Clothiers Company to provide uniforms to outfit his army, but in his haste, skipped town without paying the £453.3s he owed. With interest, that debt in 2008 would have been £47,500.

Source: “Historical Notes: Battle of Worcester and its Aftermath,” in The Baron and the Lady, book two in the “Whitleigh series” by Abigail Dane. http://TransitionsUnlimited.biz, AbigailDaneRomance@gmail.org.

Abigail Dane

Abigail DaneResources: Atkinson, Charles Francis (1911) "Great Rebellion#The Third Scottish Invasion of England" in Chisholm, Hugh Encyclopædia Britannica12 (11th ed.) Cambridge University Press pp. 420–421. Also, some background info and images are from the Military Wiki (http://military.wikia.com/wiki/Battle_of_Worcester)

Published on October 05, 2016 00:00

September 30, 2016

A TOUR GUIDE IN ENGLAND: DAY 5 - PART ONE - ARRIVAL AT BASLOW

Day 5 saw Diane and I getting the train from St. Pancras to Chesterfield, with our ultimate destination being Baslow and, eventually, Chatsworth House.

From the station in Chesterfield, we made our way to Baslow and were greeted by the sight of sheep, dozens of them, in the fields behind our hotel, the Cavendish.

Have I ever mentioned how much I love sheep? It turns out that Diane does, too. We were in alt as we left our bags at the door and stood watching them, and listening to their Baaaahing for some time.

Eventually tearing ourselves away, Diane and I entered the Cavendish Hotel, owned by the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire. In fact, it was the late Duchess of Devonshire, Deborah (nee Mitford) who had worked so hard to restore, decorate and open the hotel in 1975.

Deborah, Duchess of Devonshire

Deborah, Duchess of DevonshireThe hotel began life as the Peacock Inn and bcame part of the Devonshire estate around 1830, when it was acquired from the Duke of Rutland. Being such a fan of Debo and Chatsworth both, I had been looking forward to our stay at the Cavendish for some time. I'm happy to say that I wasn't disappointed.

We were given the Burlington Room

After dropping our bags in the room, Diane and I headed out to explore Baslow further.

The village offers two pubs, one of which is the Wheatsheaf, above and below.

Baslow is a quintessential English village, with bags of charm round every corner.

After soaking up the atmosphere, we found that it was just barely three o'clock and so we decided that there was enough time to fit in a walk to Chatsworth House and set off in giddy anticipation, like two kids waking up on Christmas morning. Chatsworth, here we come!

You may be glad to know that a stay in Baslow and a visit to Chatsworth House are both on the itinerary for Number One London's 2017 Country House Tour.

Part Two Coming Soon!

Published on September 30, 2016 23:30

September 28, 2016

GUEST POST BY AUTHOR ABIGAIL DANE, PART TWO

GUEST POST BY AUTHOR ABIGAIL DANE, PART TWO

From Victoria: Abigail Dane, author of The Pirate and the Virgin, presents the second installment of her research notes. Welcome back, Abigail!

Battle of Worcester and its AftermathPart 2 of 3

Cromwell’s army took on its own grueling march—20 miles a day in extreme heat for seven days—to reach Ferrybridge on August 19th. Once again, the ever-pragmatic Worcester decided to align itself with the faction occupying it at the time. Cromwell’s New Model Army forces were, by then, 31,000 strong. Delaying the battle just long enough to build two pontoon bridges, Cromwell launched his attack against Charles on September 3rd—the one-year anniversary of the victory at Dunbar. With a 2:1 troop advantage stretching over a four-mile-long arc toward the town of Worcester, Cromwell was able to push back the Royalist forces, despite fierce fighting. The Royalist retreat turned into a trouncing after the capture of Fort Royal, a redoubt on a small hill to the southeast of the town. Among Charles’ army, 3,000 were killed and 10,000 captured. Some leaders were executed; some prisoners were sent to fight for Cromwell in Ireland; and around 8,000 Scots were deported to the New World and made to labor as indentured workers there. By contrast, the Parliamentarian casualties were estimated at a mere 200. A clear and complete rout for Cromwell. The Proscribed Royalist, 1651, by John Everett Millais, (1853)After the Battle of Worcester, a young Puritan woman helps a fleeing Royalist—Charles II himself?—to escape, by hiding him in a hollow tree.

The Proscribed Royalist, 1651, by John Everett Millais, (1853)After the Battle of Worcester, a young Puritan woman helps a fleeing Royalist—Charles II himself?—to escape, by hiding him in a hollow tree.

In the next day’s report of the victory to the Speaker of the House of Commons, Cromwell famously wrote: The dimensions of this mercy are above my thoughts. It is, for aught I know, a crowning mercy.

That last sentence, later inscribed on the plaque placed on the Sidbury Gate in Worcester, reads in full:

THE LAST BATTLE OF THE CIVIL WARWAS FOUGHT AT WORCESTER ON3rdSEPTEMBER 1651

IT IS FOR AUGHT I KNOWA CROWNING MERCYOLIVER CROMWELL

NEAR THIS SPOT IN THE CITY WALL STOODTHE SIDBURY GATE, WHICH WAS STORMEDBY THE PARLIAMENTARIAN TROOPS.ERECTED BY THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATIONAND WORCESTER CITY COUNCILWITH THE AID OF PUBLIC SUBSCRIPTION1993

Thus, the Royalist Army was destroyed and the bloody and costly conflict known as the “English Civil War” finally ended. As preacher Hugh Peters put it: “…at Worcester, where England’s sorrows began…they were happily ended.” Ironically, as a result of Charles II’s ill-fated decision to detour to Worcester, the final battle was fought just where the first battle had been fought on September 23, 1642—almost exactly nine years earlier. Unable to rally his troops and realizing his cause was lost, the thoroughly defeated monarch removed his armor, found a fresh mount and escaping as darkness fell, began a harrowing six-week-long flight. At one point, he hid from the patrols in an oak tree (now referred to as the “Royal Oak”) on the grounds of Boscobel House, as depicted in Millais’ painting, The Proscribed Royalist, 1651. A fearless actor, the fugitive king sometimes hid in plain sight; on one occasion striding through a crowd of Cromwell’s soldiers; on another boldly declaring to the blacksmith who was shoeing his horse: “If that rogue Charles Stuart is taken, he deserves to be hanged more than all the rest, for bringing in the Scots.” At a time when the average man was 5’6”, the fugitive king was 6’2” and swarthy. Being so distinctive and hard to disguise made him an exceptional target. The £1,000 reward on his head and the “death without mercy” decree for anyone found helping him made him a tempting one, as well.

Source: “Historical Notes: Battle of Worcester and its Aftermath,” in The Baron and the Lady, book two in the “Whitleigh series” by Abigail Dane. http://TransitionsUnlimited.biz, AbigailDaneRomance@gmail.org.

Abigail Dane

Abigail Dane

From Victoria: Abigail Dane, author of The Pirate and the Virgin, presents the second installment of her research notes. Welcome back, Abigail!

Battle of Worcester and its AftermathPart 2 of 3

Cromwell’s army took on its own grueling march—20 miles a day in extreme heat for seven days—to reach Ferrybridge on August 19th. Once again, the ever-pragmatic Worcester decided to align itself with the faction occupying it at the time. Cromwell’s New Model Army forces were, by then, 31,000 strong. Delaying the battle just long enough to build two pontoon bridges, Cromwell launched his attack against Charles on September 3rd—the one-year anniversary of the victory at Dunbar. With a 2:1 troop advantage stretching over a four-mile-long arc toward the town of Worcester, Cromwell was able to push back the Royalist forces, despite fierce fighting. The Royalist retreat turned into a trouncing after the capture of Fort Royal, a redoubt on a small hill to the southeast of the town. Among Charles’ army, 3,000 were killed and 10,000 captured. Some leaders were executed; some prisoners were sent to fight for Cromwell in Ireland; and around 8,000 Scots were deported to the New World and made to labor as indentured workers there. By contrast, the Parliamentarian casualties were estimated at a mere 200. A clear and complete rout for Cromwell.

The Proscribed Royalist, 1651, by John Everett Millais, (1853)After the Battle of Worcester, a young Puritan woman helps a fleeing Royalist—Charles II himself?—to escape, by hiding him in a hollow tree.

The Proscribed Royalist, 1651, by John Everett Millais, (1853)After the Battle of Worcester, a young Puritan woman helps a fleeing Royalist—Charles II himself?—to escape, by hiding him in a hollow tree.In the next day’s report of the victory to the Speaker of the House of Commons, Cromwell famously wrote: The dimensions of this mercy are above my thoughts. It is, for aught I know, a crowning mercy.

That last sentence, later inscribed on the plaque placed on the Sidbury Gate in Worcester, reads in full:

THE LAST BATTLE OF THE CIVIL WARWAS FOUGHT AT WORCESTER ON3rdSEPTEMBER 1651

IT IS FOR AUGHT I KNOWA CROWNING MERCYOLIVER CROMWELL

NEAR THIS SPOT IN THE CITY WALL STOODTHE SIDBURY GATE, WHICH WAS STORMEDBY THE PARLIAMENTARIAN TROOPS.ERECTED BY THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATIONAND WORCESTER CITY COUNCILWITH THE AID OF PUBLIC SUBSCRIPTION1993

Thus, the Royalist Army was destroyed and the bloody and costly conflict known as the “English Civil War” finally ended. As preacher Hugh Peters put it: “…at Worcester, where England’s sorrows began…they were happily ended.” Ironically, as a result of Charles II’s ill-fated decision to detour to Worcester, the final battle was fought just where the first battle had been fought on September 23, 1642—almost exactly nine years earlier. Unable to rally his troops and realizing his cause was lost, the thoroughly defeated monarch removed his armor, found a fresh mount and escaping as darkness fell, began a harrowing six-week-long flight. At one point, he hid from the patrols in an oak tree (now referred to as the “Royal Oak”) on the grounds of Boscobel House, as depicted in Millais’ painting, The Proscribed Royalist, 1651. A fearless actor, the fugitive king sometimes hid in plain sight; on one occasion striding through a crowd of Cromwell’s soldiers; on another boldly declaring to the blacksmith who was shoeing his horse: “If that rogue Charles Stuart is taken, he deserves to be hanged more than all the rest, for bringing in the Scots.” At a time when the average man was 5’6”, the fugitive king was 6’2” and swarthy. Being so distinctive and hard to disguise made him an exceptional target. The £1,000 reward on his head and the “death without mercy” decree for anyone found helping him made him a tempting one, as well.

Source: “Historical Notes: Battle of Worcester and its Aftermath,” in The Baron and the Lady, book two in the “Whitleigh series” by Abigail Dane. http://TransitionsUnlimited.biz, AbigailDaneRomance@gmail.org.

Abigail Dane

Abigail Dane

Published on September 28, 2016 00:00

Kristine Hughes's Blog

- Kristine Hughes's profile

- 6 followers

Kristine Hughes isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.