Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 51

February 7, 2017

Number One London Tours selected by VisitBritain

We’re thrilled to be able to share the news that VisitBritain (The British Tourist Authority) has invited Number One London Tours to be one of the selected international travel buyers at the ExploreGB Conference, VisitBritain’s flagship annual event, beginning on March 1 in Brighton. The event offers invitees an invaluable opportunity to meet and network with Great British and Irish tourism suppliers and … Continue reading "Number One London Tours selected by VisitBritain"

Published on February 07, 2017 11:23

February 3, 2017

A RETURN TO REGENCY ENGLAND

What, or who, epitomizes the Regency Period for you?

Is it the Prince Regent, afterwards King George IV?

Brighton's Royal Pavilion?

Almack's Assembly Rooms?

Or perhaps Regency fashions?

Whatever it is that your mind's eye conjures up when you think of "Regency England," chances are that you'll find it on the itinerary for Number One London's Regency Tour in June. This immersive experience will bring you up close and personal with the people and places that define the Regency era.

Author Louise Allen

Beginning the Tour in London, we'll walk the same streets that would have been familiar territory to the Prince Regent, Beau Brummell and Jane Austen. Our guide for the day will be Louise Allen, author of Walks Through Regency London and Walking Jane Austen's London .

Along the way, we'll visit many of the sites associated with Regency London, whether they be well known buildings and locations or hidden gems, including White's Club, Almack's, the Burlington Arcade, St. James's Square and the Red Lion pub.

St. James's Palace

St. James's Palace Fortnum & Mason

Fortnum & Mason Beau Brummell's London townhouseAlso on our London itinerary is a trip to the V & A, the Victoria and Albert Museum, where our group will attend a Specialist Talk on the fashions, social life, royals and other aspects of the Regency period. After dinner, Louise Allen will provide us with background on Brighton's role during the Regency before we head there ourselves the next day, stopping en route to visit Grade I listed Petworth House, complete with an extensive number of preserved servants quarters. ,

Beau Brummell's London townhouseAlso on our London itinerary is a trip to the V & A, the Victoria and Albert Museum, where our group will attend a Specialist Talk on the fashions, social life, royals and other aspects of the Regency period. After dinner, Louise Allen will provide us with background on Brighton's role during the Regency before we head there ourselves the next day, stopping en route to visit Grade I listed Petworth House, complete with an extensive number of preserved servants quarters. ,

Petworth House

Petworth HouseIn Brighton, we'll be staying at The Old Ship, a Georgian seafront hotel that still retains the Regency Assembly Rooms where the Prince Regent himself opened many fashionable entertainments. While in Brighton, we'll be given a private tour of George IV's "Marine Palace," the Royal Pavilion, scene of so many events associated with 19th Century England. We'll embark on a walking tour of Brighton with local guide Jackie Marsh Hobbs and we'll tour the Regency Townhouse in Hove, where we shall also attend a Regency Soiree complete with our guests and servants in period costume.

The Regency Townhouse, Brunswick Square

The Regency Townhouse, Brunswick SquareOur return journey to London includes a tour of Polesden Lacey, the Regency house purchased by million-heiress Margaret Greville, who famously said, "Most people leave their money to the poor. I intend to leave mine to the rich." And she did, leaving her fabulous collection of diamonds to the Queen Mother and her house to the National Trust.

Polesden Lacey

Polesden LaceyOur final stop on the Tour is Buckingham Palace, where the majority of the rooms reflect the taste of George IV, who commissioned John Nash to transform Buckingham House into a palace. Many of the furnishings we'll see were purchased or made specifically for Carlton House, George IV's London home when still Prince of Wales. Our visit includes a guided tour of Her Majesty's gardens, where we'll find the Waterloo Vase commemorating the Duke of Wellington's victory at Waterloo in 1815. Perhaps the highlight of the Tour is that it will bring together a group of people with at least one thing in common - their love for the Regency period. Along the way, we'll be discussing our particular subjects of interest and all of the social, political and royal aspects of early 19th century history, all while creating new memories and making new friends.

Complete itinerary and full details regardingThe Regency Tour can be found here.

Published on February 03, 2017 23:00

January 31, 2017

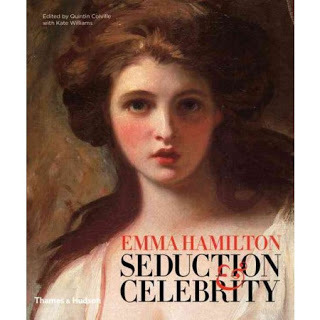

ON THE SHELF: REVIEW OF EMMA HAMILTON: SEDUCTION & CELEBRITY

By Guest Blogger Jo Manning

This sumptuous accompaniment – replete with gorgeous full-color and some black and white images -- to the exhibition currently showing at The National Maritime Museum in Greenwich (until April 17th) comprises essays by Quintin Colville; Vic Gatrell; Christine Riding; Jason M. Kelly; Gillian Russell; Margarette Lincoln; Hannah Greig; and Kate Williams on different aspects of the controversial Emma Hamilton’s life, legend, and times.

I’ve been to two previous art shows that featured Emma Hamilton and other Georgian celebrities: Joshua Reynolds And The Creation of Celebrity (at the Tate Britain in 2005), and the George Romney exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery in 2002. Both were exemplary, dedicated to these superb portraitists and their famous subjects. These sitters became instant celebrities owing to the prints of the portraits becoming widely disseminated. (These prints generated a bit of nice income for the painters, as well.) The caricaturist Gillray illustrated the popularity of these prints in his well-known “Very Slippy Weather,”showing Londoners entranced by the latest prints for sale at stationers’ shops.

Emma Hamilton (born 1765-died 1815) was also variously known as Amy/Amey/Emy/Emily Lyon and Emma Hart until she married Sir William Hamilton, British envoy (ambassador) to the Court of Naples, thus becoming Lady Hamilton. She was one of the most controversial – and, yes, notorious -- women of her time. Much has been written about her but there remains a good deal of speculation, as well. (Among the best-written biographies and novels of her, in my opinion, are these: Williams, Kate, England's Mistress: The Infamous Life of Emma Hamilton , 2006; Fraser, Flora, Beloved Emma: The Life of Emma, Lady Hamilton, 2004; and Susan Sontag, The Volcano Lover: A Romance , 1992.)

For starters, she was an unqualified beauty: a perfect oval of a face; thick, wavy, cascading auburn tresses; big-eyed; a rosebud mouth; and a complexion described by one besotted writer as a “velvet skin of lilies and roses”. Surprisingly tall, with good, square shoulders and a substantial bosom, she defied the “pocket Venus” model prized by prevailing18th century aesthetic standards. A killer combination, this, that pouting baby face and a curvy, womanly figure. Who would not want to paint her? More to the point, who would not want to be her lover?

Emma Hart as a Bacchante, circa 1785

Emma Hart as a Bacchante, circa 1785Biographies and other writings on Emma find more ample material in the second and last third of her life than in the first. Yes, she grew up poor; yes, she worked in menial positions as a young teen; yes, she moved to London at one point; yes, men began to notice her. What is uncertain is when and how she became a sex worker. Did her mother actually pimp her out at the age of fourteen? Did she work the streets or was she in a brothel? At any rate, we are on more solid ground when she is taken up by Sir Harry Fetherstonhaugh (this name is pronounced “Fanshawe”), a wealthy, dissolute rake who nonetheless has her take up the ladylike sport of horse-riding (“To hounds!”) and teaches her more genteel manners. (She was said to have a vulgar speaking voice and bad diction; her spelling, from letters that remain, show her bad spelling, but many people then were bad spellers.)

He dumps her, however, when she becomes pregnant. She is about sixteen when she is sent away – and the record is not clear whether or not this child was Fetherstonhaugh’s or Greville’s or another man in their set, Jack Payne -- and gives birth to a girl, said to be named Emma Carew. (She was also known as Emma Hartley; after years as a teacher/governess she died alone in Florence and is buried in the English Cemetery. It appears she’d had a sad life.)

After giving birth, she left the child to be raised by a relative in the country and took up with this man in Fetherstonhaugh’s set, Charles Greville, who refused to have another to do with the baby and further set about further “improving” Emma in manners, diction, et cetera. Greville, who was the nephew of the very wealthy Lord Hamilton, but not well-off himself, was a bit of a control freak, from all I have read about him and which these essays confirm. It was Greville who introduced her to the portrait painter George Romney….and thereby hangs quite a tale. And here is Romney looking his moodiest, in an unfinished self-portrait (circa 1781/2):

I myself have researched and written about Romney’s obsession with Emma, whom he painted at least sixty times and sketched many more times. At his death, notebooks were found filled with drawings – many unfinished -- of his muse Emma Hart – as she was then known. Romney was a strange old cuss. Extremely talented – he became one of the most renowned portraitists in England – but he was prone to serious bouts of depression (it apparently ran in his family). He was a very moody man. Emma Hart enriched his life, and when she was gone from it, he went even more downhill mentally.

Emma Hart In A Straw Hat

Emma Hart In A Straw HatThe only quibble I have with the uniformly excellent essays making up this book is in the Christine Riding piece. Emma Hart sat for George Romney some nine years. Nowhere in all the background reading and research I did for my guest blog for Number One London did I find any evidence that there was anyone else in that studio save Romney and Emma. I never saw mention of a “chaperone” nor of any friends/acquaintances of Greville or Emma dropping in. And this is telling, because sittings for artists were social occasions; observers sat and gossiped and were served tea, etc. This was the norm. One sitting could take up to an hour; these sittings were longer. Again, never, ever, did I find any of this normal way of conducting sittings followed by Romney with Emma. Greville, to my knowledge, simply would not allow this.

Emma Hart as Circe, painted by George Romney c1782… Exquisite!

Emma Hart as Circe, painted by George Romney c1782… Exquisite!Charles Greville was an extremely jealous and controlling man, possessive to a rather sickening degree, in my opinion. Emma Hart was his possession; he did not want to share her with anyone, even in the benign setting of sitting for a portrait. All I read led me to believe that those two, artist and subject, were alone…together. For NINE years! And I wondered, did they become lovers? It’s tantalizing to imagine this, but there is no solid proof. What seems to be evident, however, is that Emma opened up to Romney as she was posing and entertained him by singing and dancing and having fun. (I reckon she did not have much fun in her relationship with Greville, given his rigid personality.)

And, although over the years people have made fun of Emma and her “Attitudes” – i.e., the dramatic poses she struck to entertain guests – there needs to be, I think, an objective re-examination of her talents, both with these poses and with her singing. (She did hang out with theatre people when she was younger and may even have appeared onstage.) Apparently she wasn’t as untalented as so many reported over the years. I found that re-appraisal fascinating…and it confirmed to me that so much of what was written at the time and subsequently thereafter – much of it simply repeating the same anecdotes -- was not to be trusted. (I found this to be true when I was writing the biography of Grace Dalrymple Elliott, My Lady Scandalous . There is a lot of misinformation/misinterpretation out there and one has to be cautious.)

Perhaps my favorite portrait of Emma Hart by George Romney

Perhaps my favorite portrait of Emma Hart by George RomneyWhen Emma Hart was given to Lord Hamilton by his nephew (yes, she was a gift, as she was, after all, his possession), she was eagerly received. Greville was reportedly tired of her and, assiduously searching for a wealthy woman to marry, Emma was in his way. By sending her to Naples on a ruse (oh, yeah, go on ahead, I’ll be joining you directly!), he accomplished his purpose. The much older, lonely man, besotted by her beauty, took her in and eventually proposed marriage to her. (She was 21 when Greville rid himself of her; Hamilton was about 56. They married when Hamilton was 61 years old; his first wife, an heiress, had died before Emma appeared on the scene and he’d been alone for some years.)

Gillray caricature making fun of Lord Hamilton’s interest in Classical antiquities and volcanoes (he was a renowned amateur volcanologist), with images of Emma and Lord Nelson in the upper left corner, indicating he’d been made a cuckold

Gillray caricature making fun of Lord Hamilton’s interest in Classical antiquities and volcanoes (he was a renowned amateur volcanologist), with images of Emma and Lord Nelson in the upper left corner, indicating he’d been made a cuckoldMost of you may know the rest of this celebrated story. Emma – now Lady Hamilton and ensconced in luxury far beyond her imagination when she was walking the London streets and/or working in a brothel – met Lord Nelson, the famed British admiral and hero of Trafalgar, and Lord Hamilton – bless his heart – was toast.

The details can be found in the essays, but a last word about Emma’s child(ren) with Nelson is perhaps appropriate here. She had Horatia, who lived to a ripe old age, the wife of a minister and the mother of a slew of children, whose maternity Emma never acknowledged publicly, and possibly one or two other children, one of whom was said to have died very young or at birth. One or two sources I read in my research implied that there were twin girls, one of whom was sent to an orphanage, the other having died or disappeared. Sadly, it did not appear that Emma was much of a mother (though some sources said she was close to Emma Carew, her first daughter), but there is not much to go on to substantiate what happened to these later, mysterious twins…if they indeed ever existed at all, poor lost babes.

Lord Nelson, Hero of the Battle of the Nile and of Trafalgar

Lord Nelson, Hero of the Battle of the Nile and of TrafalgarThis is quite a wonderful compilation with superb illustrations, fast reading, and an excellent introduction to the life and loves of a singular woman. Enjoy the reading and perhaps shed a tear or two for Emma Hamilton’s last tawdry years. So many women like her wound up in France, dying there, forgotten. (My biography subject died there, as did the actress mistress of King William IV, Dorothy Jordan, along with other discarded women.) Nelson wanted Emma taken care of by the country he’d served so well; well, she wasn’t.

And, if you can, visit the exhibit at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London before it closes. As you can tell from the few sample images here, it is a feast for the eyes.

Quinton Colville’s introductory essay, “Re-imagining Emma Hamilton,” gives an excellent overview of the mythology and reality surrounding this woman; he is the Curator of Naval History at the National Maritime Museum in London. There are six full and informative articles in this companion to the exhibition at the National Maritime Museum, starting with historian Vic Gattrell, who teaches at Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge; his essay is “Sexual Exploitation And The Lure Of London,” a subject on which he has written extensively. Christine Riding holds the position of Head of Arts and Curator of the Queen’s House at the National Maritime Museum; she was previously at the Tate Britain, where she curated 18th and 19thcentury British art; her essay is “Romney’s Muse: A Creative Partnership In Portraiture”.

Jason M. Kelly takes us to the middle part of Emma Hamilton’s career, to Naples, where, as the wife of the British ambassador, she moves in very different circles and we take a look at “A Classical Education: Naples And The Heart of European Culture.” Kelly is an associate professor at Indiana University-Purdue and directs the Arts and Humanities Institute there. Gillian Russell penned “International Celebrity: An Artist On Her Own Terms”; Russell writes on fashionable women and on theatre in Georgian London.

Rounding out these essays are Margarette Lincoln (“Emma And Nelson: Icon And Mistress Of The Nation’s Hero” and Hannah Grieg on Emma’s last sad years with “Decline And Fall: Social Insecurity And Financial Ruin.” ) Lincoln is a specialist in English naval history and served as Deputy Director of the National Maritime Museum for several years; she is now a visiting professor at the University of London. Grieg is an academic who is now at the University of York, lecturing on 18thcentury British social, cultural, and political history; much of her research centers on the lives of the elite class in that society.

A special treat at the end of this fascinating book is biographer Kate Williams’ take on “Emma Hamilton In Fiction And Film.” Williams is a professor of history at the University of Reading and author of England’s Mistress .

Poster for Vivien Leigh/Laurence Oliver biopic That Hamilton Woman!

Poster for Vivien Leigh/Laurence Oliver biopic That Hamilton Woman!EMMA HAMILTON: SEDUCTION & CELEBRITY , edited by Quintin Colville with Kate Williams, Thames & Hudson/Royal Museums Greenwich, 2016, 280 pages

Published on January 31, 2017 23:00

January 27, 2017

It Isn't Hoarding if It's Books ! And Music !! The Role of Georgian and Regency Women in the Preservation of England's Musical Heritage

Henry Purcell (10 September, 1659 – 21 November, 1695) is considered England’s greatest composer of the Baroque Era. Named one of the first British composers of significance, he was often called “Orpheus Britannicus”and his contribution to the musical heritage of his native land is immeasurable.

Henry Purcell

Henry PurcellImagine then, the excitement stirred in the musical world in 1964, when Nigel Fortune, Purcell scholar, announced the discovery of a previously unknown ode by Purcell in a four-volume manuscript collection of the composer’s works at Tatton Park in Cheshire. ‘The Noise of Foreign Wars’ is preserved as a fragment in a bound collection first copied by Philip Hayes (1738-1797) Professor of Music at Oxford. After Hayes’s death, the collection was owned by Samuel Arnold (1740-1802) composer and conductor of the Academy of Ancient Music. In May of 1803, the collection was purchased by Mark Masterman Sykes of Sledmere in Yorkshire.

Sledmere House - Yorkshire

Sledmere House - YorkshireHow did it end up in the music room at Tatton Park? How did all of these men – a music professor, a composer and conductor, and a wealthy landowner in Yorkshire manage to save such a treasure so that Nigel Fortune might unearth it three hundred years after it was written? They didn’t. Well, they didn’t do it by themselves. It took….

A woman.

In the late seventeenth century, gentlemen of means began to collect books and art to display in their homes as a mark of their wealth and status. After all, no young man returned from his Grand Tour without some sort of souvenirs. (Preferably the sort for which one did not need to visit one’s physician.) Long galleries in which to display paintings and works of art and libraries became essential parts of the Society town-house and the country “ancestral pile”. Some homes were even designed or redesigned to feature these architectural aspects prominently.

In 1809, the biographer Thomas Frognall Dibdin called the obsessive collection of books by the nobility ‘bibliomania’. In 1812, an exclusive bibliophile society, the Roxburghe Club, was formed. One of its founding members? Mark Masterman Sykes. He was best known for his collection of books and engravings. By the end of 1810, his library at Sledmere was considered one of the finest in England.

And in 1807, Mark Masterman Sykes gifted his four-volume collection of Purcell’s music to his newly married sister, Elizabeth Sykes Egerton, of Tatton Park. (You thought I was never going to get there, didn’t you?)

Elizabeth Sykes, (Mrs Wilbraham Egerton), c. 1795

Elizabeth Sykes, (Mrs Wilbraham Egerton), c. 1795portrait miniature by Abraham Daniel of Bath

Elizabeth Sykes was an accomplished musician at an early age. As a young girl, her music collection was like that of any musically inclined lady. Collections of the sort made by the accumulation of pieces with social occasions and entertainment in mind. Not to be taken seriously, or so the majority of Society (men) believed.

Her first music books are dated 1790 and are inscribed with her name – Miss Sykes. They consist of pre-ruled oblong copybooks into which she copied music from her piano lessons, folk songs, and catches. One book actually has two handwritings in it – one starts at one end of the book and the other starts at the other end. This was a common practice in copying music, especially when one wanted to divide the types of compositions – say sonatas at one end and hymns at the other. In some instances, a composition might be started, messed up and started over in a better fashion to the finish.

Her copybooks from 1799 and 1801 were larger pre-ruled music books from the London music publisher Robert Birchall. The covers were a bit more elegant with pages for her to inscribe her name and the details of the music in each one. There were vocal ornaments and notations in these in multiple hands. Even entire pieces appear to be copied by others. This can be attributed to the common practice of passing around these books to friends, the same way young ladies today might pass around CD’s or I-pods.

Elizabeth Sykes also purchased a great deal of printed sheet music. Fortunately for us, she signed all of her music as it was purchased. Therefore, it is easy to differentiate between the music she bought whilst unmarried, and those pieces she purchased after she married her cousin, Wilbraham Egerton, in 1806 and moved her collection to Tatton Park. (I know. She married her cousin, but he did play the cello.)

Tatton Park - Cheshire

Tatton Park - CheshireThe collection of printed sheet music, because it was the realm of women, did not signify as collecting the way the accumulation of books and art did. However, these collections often contain copies of popular songs printed the night after their first performance at Vauxhall or at one of London’s theatres, never to be seen again. It is thought researchers have only begun to scratch the surface of many of these collections.

Elizabeth had a great deal of her music bound in indexed volumes. Her diligence and attention to her collection produced folio compilations as handsome as the albums of engravings and illustrated books on antiquities to be found in any bibliophile’s library. Her valuation of her music resulted in it being shelved and cared for the same way her husband’s and brother’s collections of books were.

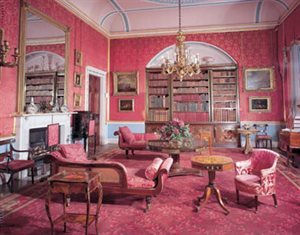

Music room at Tatton ParkAs a result, in addition to the Purcell volumes gifted to Elizabeth by her brother, the music at Tatton Park includes rare numbers of Benjamin Goodison’s projected complete edition of Purcell begun in 1789. Nearly an entire shelf contains Samuel Arnold’s collection of Handel’s complete works. It is the first complete edition of any composer, pre-dating the Mozart Gesamtausgabe.

Music room at Tatton ParkAs a result, in addition to the Purcell volumes gifted to Elizabeth by her brother, the music at Tatton Park includes rare numbers of Benjamin Goodison’s projected complete edition of Purcell begun in 1789. Nearly an entire shelf contains Samuel Arnold’s collection of Handel’s complete works. It is the first complete edition of any composer, pre-dating the Mozart Gesamtausgabe. Dove sei by G.F. Handel (from the Samuel Arnold collection at Tatton Park)

Dove sei by G.F. Handel (from the Samuel Arnold collection at Tatton Park)I have gone into great detail about the collection of music at Tatton Park and the incalculable debt we owe Elizabeth Sykes Egerton. Like those researchers who have renewed the world’s interest in these collections, I have only scratched the surface of this fascinating topic. There are impressive collections of music accumulated and preserved by Georgian and Regency women all over England. Lydia Hoare Acland’s collection at Killerton House in Devon. Mary Egerton Sykes music books at Sledmere in Yorkshire. Over two thousand items in Miss Cornewall’s collection at Mocca’s Court in Herefordshire.

The list goes on and musicologists are prowling the libraries and collections of stately homes all over England in search of the next great musical treasure. All tucked safely away by those accomplished young ladies, bluestocking women, and musical dragons who loved their music enough to preserve it for all of us.

I’ll be posting more on this subject in my next post. Not only more about the role women played in preserving England’s musical heritage, but also how their love of music changed the architectural design of many houses built during the late Georgian and Regency eras to accommodate that love.

Published on January 27, 2017 23:00

January 24, 2017

AUTHOR LOUISA CORNELL JOINS OUR FAMILY

Victoria and I are thrilled to announce that our dear friend Louisa Cornell has joined the Number One London editorial team. We couldn't be happier! Many of you will already know Louisa who, in addition to her editorial work and her own writing projects, is also President Elect of the Beau Monde Chapter of Romance Writer's of America.

Louisa has been a friend of this blog since it's beginnings six years ago and has been a friend to Victoria and myself for a considerably longer period of time (decades!).

Louisa, on the left, with Victoria at one of the many writing conferences they've attended through the years.

Louisa, on the left, with Victoria at one of the many writing conferences they've attended through the years.As a champion of romantic fiction and all things British, Louisa will be bringing her unique talents and her passion for researching the history of Great Britain to Number One London soon and you can look forward to reading her enlightening posts, reviews of fiction and non-fiction books and to many surprises yet to be announced.

Welcome Louisa!

And a note from Louisa -

I cannot begin to tell you what a thrill and honor it is to join the Number One London team! I think I've spent so much time loitering about here the last six years, Victoria and Kristine have decided to put me to work. And I could not be happier! This blog has been and continues to be a delightful respite from the everyday world, a lovely neverending vicarious vacation to the UK, and a source of entertainment and enlightenment for all who love 18th and 19th century England and the romances set in those eras. I look forward to contributing in my own small way to the myriad charms enjoyed by the most discerning, supportive, and loyal denizens on the web - Our Visitors!

Thank you so very much, Kristine and Victoria!

And thank you to Number One London's Fabulous Followers!

And while we're at it, Victoria, Kristine and Louisa would like to thank all of our guest bloggers who have contributed to the blog in the past. Our most prolific (and much loved) pal, author Jo Manning has been providing guest posts to Number One London since the beginning, with many of her posts featuring 18th and 19th century artists and their sitters. Look for more book reviews and posts from Jo coming soon. Over the past year, we've welcomed guest posts from the following authors: Abigail Dane, Marilyn Clay, Louise Allen, Diane Gaston (Perkins), Beth Elliot, Cheryl Bolen, Amanda McCabe, Tracy Grant, Kerryn Reid and Michelle Styles. If you've uncovered an historic tidbit you'd like to post about, or a favourite historic person, place or thing, please do get in touch. We'd love to add you to our roster of guest bloggers.

Published on January 24, 2017 23:00

January 20, 2017

GLIMPSES OF KING WILLIAM IV AND QUEEN ADELAIDE - PART THREE

Boston House, Brentford

Boston House, BrentfordOur series on the lives of King William IV and Queen Adelaide continues with excerpts from a book entitled, Letters the Late Miss Clitherow of Boston House, Middlesex, With A Brief Account of Boston House and the Clitherow Family, edited by Rev. G. Cecil White. As the Reverend himself states in his preface: "The following pages are mainly compiled from certain letters by Miss Mary Clitherow, which have come into the editor's possession. They afford glimpses of the Court at that time, with reference not so much to public functions as to their Majesties' more private relations with persons honoured with their friendship."

Our next glimpse of their Majesties is not from, but at Boston House. This unsought honour was rather deprecated, though thoroughly appreciated by their hosts, who, in spite of their intimacy with the King and Queen, never made any pretension to be more than simple gentlefolk. Colonel Clitherow was the first commoner whom William IV so honoured, probably the only one, and instances of other monarchs doing the like must be few and far between. In this case, doubtless, both their Majesties regarded it as an act of simple friendship, and not in any way as one of condescension.

'BOSTON HOUSE, 'July 10, 1834.

'On June 28, 1834, their Majesties honoured old Boston House with their company to dinner. They came by Gunnersby and through our farm at our suggestion; it is so much more gentlemanly an approach than through Old Brentford.

'The people were collected in numbers and Dr. Morris's school, and they gave them a good cheer. We then let the boys through the garden into the orchard by the flower-garden, where my brother had given leave for the neighbours to be, and it seemed as if two hundred were collected.

'We had our haymakers the opposite side of the garden, and kept the people, hay-carts, etc., for effect, and it was cheerful and pretty. The weather was perfect, and the old place never looked better.

'They arrived at seven, and we sat down to dinner at half-past. During that half hour the Queen walked about the garden, even down to the bottom of the wood. The haymakers cheered her, and had a pail of beer, and when she came round to the house, instead of turning in she most good-humouredly walked on to the flower-garden, and stood five minutes chatting to the party, which gave the natives time to get her dress by heart. It was very simple--all white, little bonnet and feathers.

'The King had a slight touch of hay asthma, the Princess Augusta a slight cold, and therefore they declined going out, which separated the party, and was a great disappointment to the people. We had police about to keep order, the bells rang merrily, and all went well. We received them in our new-furnished library.

'When dinner was announced the King took Jane, my brother the Queen, and they sat on opposite sides, the Duchess of Northumberland[*] the other side of the King, Lord Prudhoe[**] the other side of the Queen, General Clitherow and General Sir Edward Kerrison top and bottom, and the rest as they chose--Princess Augusta, Lord and Lady Howe, Lady Brownlow,[***] Lady Clinton,[****] Lady Isabella Wemyss, Colonel Wemyss, Miss Clitherow, Miss Wynyard, Mrs. Bullock, and Mr. Holmes. That makes nineteen. The Duke of Cumberland[*****] was to have been the twentieth, but Mr. Holmes brought a very polite apology just as we were going in to dinner. The House of Lords detained him.

Princess Augusta Sophia, sister of King William IV

'As to the dinner, it was so perfect that it was impossible to know a single thing on the table, and that, you know, must be termed a proper dinner for such a party. My brother gave a carte blanche to Sir Edward Kerrison's Englishman cook, and, to give him his due, he gave us as elegant a dinner as ever I saw. Our waiting was particularly well done--so quiet, no in and out of the room. Everything was brought to the door, and there were sideboards all round the room, with everything laid out to prevent clatter of knives, forks, and plates. Etiquette allows the lady's own footman in livery, and we had ten out of livery, the King and Queen's pages, seven gentlemen borrowed of our friends, and our own butler. They all continued waiting till the ladies left the room.

'We were well lit, wax on the table and lamps on the sideboards, and many a face I saw taking a peep in at the windows. The room was cool, for the Queen asked to have the top sashes down.

'The King was not in his usual spirits. He said had it been the day before he must have sent his excuses. The Queen was all animation, and the rest of the party most chatty and agreeable. The King bowed to the Queen when the ladies were to move.

'Our evening was short, as they went at half-past ten. The Princess played on the piano, and my brother and Mrs. Bullock sang one of Ariole's duets at the Queen's request. When they went the sweep was full of people to see them go, and their Majesties were cheered out of the grounds.

King William IV

King William IV'We had with us our little nephew Salkeld,[*] whom my brother puts to Dr. Morris's school. He came in to dessert, a day the child can never forget. The King asked him many questions, which he answered distinctly, with a profound bow, and then backed away. He looked so pretty, for the awe of Royalty brought all the colour to his cheeks. I felt rather proud of him, he did it so gracefully. The Queen told him she hoped he would make as good a man as his excellent uncle. After dinner the Princess Augusta called him to her in the drawing-room, saying, "I like that little fellow's countenance; he is quite a Clitherow." She talked to him of cricket, football, and hockey, telling him when she was a little girl she played at all these games with her brother, and played cricket particularly well.

'That we are proud of this day we cordially own, for my brother is the first commoner their Majesties have so honoured; but we feel we ought not to have done it. When Jane, with her honesty, told the Queen we were not in a situation to receive such an honour, her answer was: "Mrs. Clitherow, you are making me speeches. If it is wrong I take the blame, but I was determined to dine once again at Boston House with you.'

'The absurd conjecture of people at the expence of the day to my brother induces me to tell you what it actually was, as we should be ashamed at the sum guessed at. I have made the closest calculation I possibly can, which includes fees to borrowed servants, ringers, police, carriage of things from and to London, and I have got to L44. Never was less wine drank at a dinner, and that I cannot estimate, but L6, I think, must cover that. We had two men cooks, for he brought his friend, and we got all they asked for. Really, I think we were let off very well at L50.

[*] Wife of Hugh, third Duke, and daughter of the first Earl Powis. She was governess to H.R.H. the Princess Victoria, our late gracious Queen.

[**] Algernon Percy, second surviving son of the second Duke of Northumberland, F.R.S., and Captain R.N.; born 1792. Created Baron Prudhoe 1816. On the death of his brother he succeeded to the dukedom, which, on his death in 1865, passed to his cousin, the second Earl of Beverley.

[***] Emma Sophia, daughter of the second Earl of Mount Edgecumbe; born 1791, married, 1828, the first Earl Brownlow. She was Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Adelaide.

[****] Widow of the seventeenth Baron Clinton, Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Adelaide. In 1835 she married Sir Horace Beauchamp Seymour, K.C.H.

[*****] He became King of Hanover on the death of William IV.

[*] He became a hero in the Indian Mutiny, losing his life in volunteering to blow up the Cashmere Gate at Delhi in 1857.

Queen Adelaide

Queen AdelaideAFTER a short illness, William IV. died at Windsor Castle on June 20, 1837. On July 17 Miss Clitherow wrote as follows:

'Thank you very much for writing to me. I always enjoy your letters, and delight to hear from you. I feel I did not deserve it, so much time has elapsed since I wrote to you. But I dislike writing when the spirits are below par, and how could they be otherwise with the afflicting event which has befallen the country? Great were our apprehensions for the dear Queen when she was so ill and could attend none of the State entertainments, but the King's death never entered our ideas. On June 3 my brother went by command to Windsor. He sat with

the King while he ate his early dinner. He was cheerful and chatty, and had only sent for him for the pleasure of seeing and conversing freely with him, which he did for above an hour, and the last thing his Majesty said was, "Thank you for coming; it always does me good to see you, and very soon you and Mrs. Clitherow must come to Windsor for a few days and your sister.' How little he thought his days were numbered, and that he should never see him more! He then appeared so little ill my brother returned home quite in spirits, and on the

twentieth he was dead--only seventeen days.

'Since the Queen Dowager got to Bushey Lady Gore has written to us. The description of her resigned pious mind is beautiful, and Lady Gore[*] assures us she really hopes her health has not materially suffered from all she has gone through, particularly the last sad ceremony.

'My brother was deputed to present the address of condolence from the magistrates to the Dowager Queen. He dreaded it, but he wrote to Lord Howe to know how and when, and was answered--Queen Adelaide receives no addresses; but those she received on the throne from the City, etc., those she must receive. We are delighted at this, as it was too much to impose upon her. Addresses are pouring in from all quarters, and Lord Howe is to receive them.'

[*] Wife of General Hon. Sir Charles Gore, G.C.B., K.H., third son of the second Earl of Arran, a Waterloo officer.As Queen Adelaide received no visitors, except such as she could not refuse, in her widowhood, the King's death closed her intimate intercourse with the Clitherows. It seems, however, just to the memory of both the King and Queen to insert the following testimony to her tender affection for her husband, and her delicacy of feeling respecting his previous relations with Mrs. Jordan.

Dorothea Jordan by Hopper

BOSTON HOUSE, September 23, 1837. 'I dare say you look to me for some true account of our dear Queen Adelaide. We have not seen her, but have been much gratified by her recollection of us. She sent a most kind message by Mr. Wood, with the little book he wrote at her command of William IV.'s last days--a copy to my brother and one to me. 'Very lately we began to doubt whether we ought not to go to Bushey as we used to visit her Majesty at Windsor, and Mrs. Clitherow wrote to consult Lady Denbigh. She acted most kindly to us, for she waited an opportunity of showing the note to the Queen. Her Majesty's answer was, it would be a 'real comfort to her to see Mrs. Clitherow, but it would open the door to so many; she could not without giving great offence. Lady Denbigh added Her Majesty had received no one yet, except those whom she was obliged to admit. 'Mrs. Clitherow dined in company with Miss Hudson, one of the Dowager's Maids of Honour, whom we know very well. She gave a delightful account of the dear Queen, her mind so peaceful, always occupied, much interested with her sister and her children, constantly doing charitable acts, and for ever talking of the King, and hoping she had thoroughly done her duty. Miss Hudson was in waiting for five weeks, and the first three she was very uneasy about Her Majesty's health, and thought her sadly altered; but the last two her cough had almost entirely ceased, and she had slept remarkably well. 'You have no doubt seen the book I allude to, for 'tis now to be had for sixpence. Could anything be so extraordinary as the conduct of the Bishop of Worcester? Her Majesty sent him a copy, and he sent it to the editor of a newspaper. When the Queen read it in a public paper she was very indignant, and the gentleman who was told by her to discover who "the high dignitary in the Church" was, told us Carr, Bishop of Worcester. The man who has been quite the Court Bishop should have known better. 'One act of the Queen Dowager I must tell you: the Queen (Victoria) sent a message by Colonel Wood and Sir Henry Wheatley requesting she would take anything she chose from the Castle; she selected two--a favourite cup of the King's, in which she had given him everything during his last illness, and the picture from his own room of all his family. It was a singular picture, all the Fitz-Clarences grouped, and in the room Mrs. Jordan hanging a picture on the wall, the King's bust on a pedestal, and all strikingly like. I think it shows a delicacy of feeling to her King which was beautiful. It was a picture better out of sight for his memory. Now, this you may believe, for Colonel Wood told us. He transacted the business, and Queen Adelaide has the picture. 'Believe me, 'Yours very truly, Mary Clitherow.' Neither Queen Adelaide nor the three friends long survived the kindly monarch they loved so well. Colonel Clitherow died in 1841; his sister, who became totally blind, early in 1847; and his true and honest wife, the last of the Boston House trio, died in March of the same year.

Published on January 20, 2017 23:00

January 18, 2017

A TOUR GUIDE IN ENGLAND: GATES AND DOORS - PART ONE

Hogarth's House, London

Chelsea Physic Garden, London

Buckingham Palace

Above and all below, Baslow, Derbyshire

Published on January 18, 2017 00:30

January 14, 2017

GLIMPSES OF KING WILLIAM IV AND QUEEN ADELAIDE - PART TWO

Windsor Castle

Windsor CastleOur series on the lives of King William IV and Queen Adelaide continues with excerpts from a book entitled, Letters the Late Miss Clitherow of Boston House, Middlesex, With A Brief Account of Boston House and the Clitherow Family, edited by Rev. G. Cecil White. As the Reverend himself states in his preface: "The following pages are mainly compiled from certain letters by Miss Mary Clitherow, which have come into the editor's possession. They afford glimpses of the Court at that time, with reference not so much to public functions as to their Majesties' more private relations with persons honoured with their friendship."

Within a week or two after their last royal summons, Colonel and Mrs. Clitherow again

visited Windsor by the Royal commands, and Miss Clitherow, in her minute chronicle, shows that, while they cherished no pride of pomp or station, they fully appreciated the honour of the King's friendship:

BOSTON HOUSE, May 13, 1832.

'. . . . . . I will tell you of our Courtly doings, and how thankful we are that we just take the cream, free and independent, without rank or place--no troubles, turmoils, or jealousies. We receive the most flattering notice--and it can be from no other motive than liking us--a rare

occurrence at Court, and of which we have a right to be proud.

'Lately a command came to my brother and Mrs. Clitherow to come to Windsor Castle on the Monday and stay till the Wednesday. There were no other visitors. Nobody breakfasts with the Queen or takes luncheon unless sent for. You have your breakfast in your own sitting-room, or at the general breakfast, as you prefer. We always take the latter, but

this visit Jane was with her at every meal, the King the only gentleman admitted at breakfast, and only his sons, or very few, at luncheon. Each evening the Queen called Jane to her sofa and work-table, where, also, no one approaches but by her invitation, and on the Tuesday morning the King took my brother all round the Castle with Wyattville, giving orders and directions. I fear greatly the improving mania is coming upon His Majesty, which, in these times, will be very unfortunate.

'The Queen took my brother and Jane a long drive in her barouche. . . . . . After the drive she took them into her room, and clasped a bracelet round Jane's arm, begging her to wear it for her sake, and, as the stone was an amethyst, the A would remind her of Adelaide, and then she kissed her cheek. To my brother she presented a silver medallion of the King, telling him her name was on the back, and he must keep it for her sake. She always has something obliging and kind to say. She sent a ticket for her box at Drury Lane. It was "Admit Colonel and Mrs. Clitherow." Jane asked her if that meant two places. "No, no; the whole box, to be sure. It holds eight. But, when I name one of you, I cannot help naming both."

Sir Jeffry Wyatville

Sir Jeffry Wyatville'King William IV. forgot little me when he sent his commands. On their going in he said: "Where is Miss Clitherow? I hope illness has not prevented her.' On an explanation, "Then next Monday meet us at dinner at Bushey, and bring your sister with you.' And we did meet them. The King came over with Wyattville to inspect Hampton Court Palace. The Queen followed, to dine with him at their dear Bushey. They returned to Windsor at ten, the Princess Augusta to town. Only Lady Falkland and Miss Wilson attended the Queen. The company were the inmates of Hampton Court, where we have never visited, and therefore to me the dinner was dull.'

'. . . . . .The Thursday after we went to see Lady Falkland, who is on a visit to papa King. We found her, her widowed sister Lady Augusta Kennedy, and Miss Wilson very comfortably at work. They were the two Fitz-Clarences; we saw a good deal of them when they lived at Bushey.

King William IV

King William IV'A page soon came to conduct my brother to the King, another to desire we would take luncheon in the Queen's room. On entering the King called Jane by him, the Queen me; she rose up and shook hands with both. My brother went down to the general luncheon. Nothing could be more good-humoured and pleasant than they were. The King was cheerful but

silent; 'twas the day after Lord Grey's resignation. The Queen certainly in particular good spirits; the King's firmness respecting the making no peers had delighted her. They went to his apartments, and we to Lady Falkland's, and were preparing to depart, when a message

came. The Queen had not taken leave of us, and hoped we were in no hurry, but would stay and Walk with her. Of course we did. The party consisted of the Queen, Miss Eden (Maid of Honour), Miss Wilson, Lord Howe, Mr. Ashley, Mr. Hudson, Sir Andrew Barnard, and our three selves. She took us through the slopes to her Adelaide Cottage and her flower-garden to see Prince George of Cambridge at gymnastics, with half a dozen young nobility from Eton, who came once a week to play with him. We were walking nearly two hours. The Queen is very animated, and Mr. Ashley and Mr. Hudson full of fun and tricks, and amused us all much. In short, I have but one fear when with her--forgetting in Whose presence I am; her manner is so very kind, but there is dignity with it that keeps us in order.'

The Fishing Temple, Virginia Water

The Fishing Temple, Virginia Water'WINDSOR CASTLE, 'September 3, 1832.

'Here I am writing with Royal pens, ink, and paper, which last I dislike of all things, it being glazed. . . . The visitors here besides ourselves are the Duke and Duchess of

Gloucester[*]--she is too unwell to appear--Prince George of Cambridge; the Duke of Dorset; Mademoiselle d'Este; Sir Henry and Lady Wheatley, with two daughters; Lady Isabella Wemyss (Lady of the Bed-chamber), a most pleasing, lovely woman, sister to Lord Errol; Miss Johnson (Maid of Honour); Miss Wilson (Bed-chamber-woman); Mademoiselle Marienne, Lord and Lady Falkland, Sir Herbert and Lady Taylor, Sir Andrew Barnard, Sir Frederick Watson, Colonel Bowater, Mr. Hudson, Mr. Shifner, and Mr. Wood.[**] Princess Augusta and Lady Mary Taylour came every day from Frogmore, which, with the household medical man, Mr. Davis, makes a party of thirty, reckoned here a small party.

'The dinners are always princely, gold plate, quantities of wax-lights, and servants innumerable, yet very agreeable and with less of form than you could suppose possible.

'Yesterday threatened much rain, but after luncheon it cleared, and we started, four carriages, four in each and a number on horseback, and went to the Fishing Temple by the Virginia Water to see a model of a vessel to be moved by clockwork. After seeing it exhibited we all took boat, and in parties rowed about that beautiful lake. We had the

six-oared boat and various little boats. Prince George and Mr. Hudson rowed Her Majesty about, and the whole had so much ease and good-humour it was very delightful.

'Our evenings are always the same, the band playing most beautifully, work-tables and cards for those who chuse.

'The first evening the Queen called us both to her table; the second she sat with the Duchess of Gloucester till her bedtime, so that we had not much of her company. She is always about some elegant work, which she does remarkably well, and has a great deal of cheerful conversation.

'This is our third day, and we leave on Monday. Our invitations say when we are to come and when to go, which is very agreeable. We have our time to ourselves in our own sitting-room from breakfast till luncheon at two.

'So I have scribbled to you, though no post goes till to-morrow. A trio of kind regards.

'Yours truly, 'M. CLITHEROW.'

[*] H.R.H. was the King's cousin, and the Duchess was the King's fourth

sister, Princess Mary.

[**] Many of these are obviously members of the household rather than

visitors.

The following letter offers a splendid description of the festivities at Windsor for the Queen's birthday and was written from Rise Park, the seat of their cousin, Mr. Bethell,

M.P., on October 1, 1833:

'. . . . . . .Now, from the Fens I will take you to the Forest. The cottage where George IV. lived so much has been pulled down, except a banquetting room, the conservatory, and a few small rooms for the gardener. Here the preparations were made for a morning fete on the Queen's birthday [August 13], and, as a surprise to her, the magnificent Burmese tents,

which she had never seen, were put up. I never saw anything prettier than the whole scene, and the day was lovely. The tents the most brilliant scarlet, ornamented with gold and silver, silver poles, and a silvered velvet carpet, embroidered with gold and silver. The hangings,

sofas, and seats were all of Eastern splendour, and at the end was a large glass. The company was very select, and the morning dresses becoming and elegant. Two bands of music (Guards) played alternately. A guard of honour and numbers of officers were present. Everybody seemed gay and in their best fashion. The King and Queen, with about forty

guests, dined in the room, about as many more in a long, canvas room. The tables had fruit, flowers, ornaments, confectionery, a few pyramids of cold tongue, ham, chicken, and raised pies. Then you had handed to you soups, fish, turtle, venison, and every sort of meat. Toasts were given, cannon fired, and both bands united in the appropriate national airs. Altogether it was a sort of enchantment. At seven fifteen of the King's carriages and many private carriages took the party to the Castle to dress for an evening assembly, where about two hundred were asked. We were the envy of many in being allowed to go home, having had the cream of the day. Nothing could be a greater compliment than our being asked in the morning. We were the only untitled people. The King had filled the Castle, Round Tower, and Cumberland Lodge, and had not a bed to offer. So he invited us, saying: "Come at three. We dine at four. And then go away at seven, and be home by daylight, for we cannot

give you beds."

Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle'To his own birthday [August 21] we had the general invitation for the evening, and the old trio went from Boston House at seven, and got back by two. The noble Castle, so lit up, was a magnificent sight. The Queen was quite the Queen, for it was very mixed society--too much so for Royal presence. The good-humoured King asks everybody, and it was a

crowd! But she sat with the Royal Duchesses only, attended by her ladies, and she was dressed much finer than her usual style. She twice conversed with us, and when she left the room came up to us, shook each by the hand, and was so sorry we had to go home so far.

'My brother and Mrs. Clitherow called at Windsor to take leave before we left home for so many weeks, and after luncheon with her and the King, she took them into her own room to see a bust of the little niece that she nursed with such motherly affection, Princess Louise, and then gave them two prints of herself and two of Prince George of Cambridge, the best likeness I have seen of her. She said, "One for Miss Clitherow, the other for you two, because you are as one." All she does in such a gracious, pretty manner.'

PART THREE COMING SOON!

Published on January 14, 2017 00:00

January 11, 2017

A TOUR GUIDE IN ENGLAND: SIGNS - PART 4

Published on January 11, 2017 00:00

January 7, 2017

GLIMPSES OF KING WILLIAM IV AND QUEEN ADELAIDE - PART ONE

King William IV by James Lonsdale, 1830

Today we begin a series of posts that will give some insight into the personalities and home life of King William IV and Queen Adelaide, a royal pair whom, in my personal opinion, have not been enough by the history books. To illustrate just a small slice of their lives at Windsor, we offer excerpts from a book entitled, Letters the Late Miss Clitherow of Boston House, iddlesex, With A Brief Account of Boston House and the Clitherow Family, edited by Rev. G. Cecil White. As the Reverend himself states in his preface: "The following pages are mainly compiled from certain letters by Miss Mary Clitherow, which have come into the editor's possession. They afford glimpses of the Court at that time, with reference not so much to public functions as to their Majesties' more private relations with persons honoured with their friendship."

Colonel and Mrs. Clitherow lived at Boston House in Brentford along with the Colonel's

sister Mary, the author of the following letters, who was two years his senior. About the year 1824 they became acquainted with the Duke of Clarence, afterwards King William IV., who then resided at Bushey, of which park he was Ranger; and they were admitted to an unusual degree of intimacy with their Royal neighbours, observing in their intercourse with them an honesty not usually found in courtiers, but quite in keeping with the family motto,

'Loyal, yet true.' So close did this intimacy become that, after his accession, the King nicknamed Miss Clitherow 'Princess Augusta,' in allusion to her being the old maid of the family as the Princess was in his own, and when inquiring for her of Colonel or Mrs. Clitherow would say, 'How is your Princess Augusta?' It may of interest to note that in the library of Boston House were hung many portraits of the Clitherow family by leading artists of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Among these should be specially noted a pastile by Zoffany of Mr. and Mrs.and Miss Child, taken in the porch at Osterley. Mrs. Child (nee Jodrell) was the sister of Mrs. Clitherow, and afterwards married (1791) the third Lord Ducie. Miss Child married the tenth Earl of Westmoreland, and became the mother of the Countess of Jersey.

Boston House, Brentford

Boston House, BrentfordAlthough, however, the Clitherows were frequent guests at Windsor and St. James's, they were not courtiers in the common acceptation of that term. They sought neither place nor preferment, and received no signal mark of Royal favour. Miss Clitherow never even attended a Drawing Room, and the Colonel and his wife only appear to have done so on one occasion, when the Queen remarked: 'I knew Miss Clitherow would not come; it is too public. She had almost left off going out till we made her come to St. James's.' Miss Clitherow was naturally of a quiet and retiring disposition, while her own account of her introduction to the Court, and of the independent spirit which pervaded the family, is

interesting not only in itself but as illustrating the kindly sincerity of the King and Queen. Writing to an old friend in November, 1830, Miss Clitherow says:

'I can hardly believe that I feel as much at home in the Royal presence as in any other first society, but it is the fact. It is seven years that my brother and Mr. [sic] Clitherow have been noticed, but I am only just come out now. For many years my health did not allow of my

dining out, and I got so out of the habit that I avoided it, and quite escaped being asked to Bushey till the Duke became King. Before George IV. was buried they were invited; no party but the Royal brothers and sisters and the Fitz-Clarences. They did me the honour to talk of me, the King calling me my brother's Princess Augusta, in allusion to my being the old maid of the family, and then added: "I can't see why she does not some out; you must dine here Tuesday, and bring her." So the deed was done. Refuse I could not. I dined at Bushey, then twice at St. James's, then on the Queen's birthday at Bushey, and then went to Windsor Castle on Friday and stayed till after church on Sunday, and now to dinner at St. James's last Monday. So that actually [in less than five months] the little old maid of Boston House has dined seven times with King William IV., and honestly I have liked it. There is a

kindness and ease in their manner towards us that must be gratifying . . . and when we come home what a feeling of comfort we have in not being obliged to live in that circle, with all the insincerity so often belonging to courtiers! I am very sure my dear Jane's honest manner and the sound judgment which she ventures to express to Her Majesty makes

her such a favourite. Much as we are noticed, we do not court them, and never have asked the slightest favour. When they first went to Windsor our friends said: "You must drive over and put your names down." "No," Mrs. Clitherow said, "we were asked to the Queen's birthday; I will not go before the King's, it will look like pushing to be asked." And we

received our invitation to Windsor before we had called. When we came away, the King expressed a hope to see us at Brighton, as he knew we frequently went into Sussex. Our friends all were for sending us thither, but it did not suit us. Don't you like independence? As soon as they came to town we did put our names down. Miss Fitz-Clarence writes herself to Mrs. Clitherow to inform her of her intended marriage with Lord Falkland, and Mrs. Henry is employed to write and invite us to dinner to meet our own friends. So I think we rather go the right way to please them.'

Queen Adelaide

Queen AdelaideThe following extract is from a letter dated November 20, 1830 -

'We had dined there (St. James's Palace), and it seems almost like vain boasting, but it was

a party made for us. When the King told Mrs. Henry to write and invite us, he said: "I shall only ask Colonel Clitherow's friends that I have met at Boston House." And it was the Duke of Dorset,[*] Lord[**] and Lady Mayo, the Archbishop and Mrs. Howley, the rest of the company his own family, the Duke of Sussex,[***] and a few of the Household-in-waiting. There could not be a greater compliment. The Queen shows a decided partiality for Mrs. Clitherow. In the evening she sat down to a French table, and called to her to sit by her. The King came in and sat down on the other side of Mrs. Clitherow. She rose to retire, but he

said: "Sit down, ma'am--sit down." Two boxes were placed before him, and he said to Miss Fitz-Clarence[****]: "Amelia, I want pen and ink." Away she went, and brought a beautiful gold inkstand, and he signed his name, I am sure, a hundred times, passed the papers to Mrs. Clitherow, and she to the Queen, who put them on the blotting-paper, then folded

them neatly and put them in their little case to enable them to pack into the boxes again, conversation going on all the time. When the business was over, the King took my brother to a sofa, and chatted a long time, inquiring into the state of things in our neighbourhood,

policemen, etc. The Queen's new band was playing beautifully all the evening, which she said she had ordered to have my brother's opinion. The late King's private band cost the King L18,000 a year. It was dismissed, and a small band is formed--I believe I may say all English, and many of the juvenile performers whom she patronizes. Her dress was

particularly elegant, white, and all English manufacture. She made us observe her blend was as handsome as Lady Mayo's French blend. "I hope all the ladies will patronize the English blend of silk," she said. She is a very pretty figure, and her dress so moderate, sleeves and head-dress much less than the hideous fashion.'

[*] Charles Sackville Germain, fifth Duke of Dorset, K.G., was a son of the first Viscount Sackville, and born 1767. He became Viscount Sackville 1785, and succeeded his cousin, the fourth Duke of Dorset, in 1815.

[**] John Bourke, fourth Earl of Mayo, born 1766, succeeded his father 1794.

[***] H.R.H. was the sixth son of H.M. George III., born 1773, and was unmarried.

[****] The King's youngest daughter, by Mrs. Jordan; born 1807, married, 1830, the ninth Viscount Falkland.

The following letter bears testimony to the King's conscientious discharge of duty and to royal life at Windsor Castle.

'April 13, 1831.

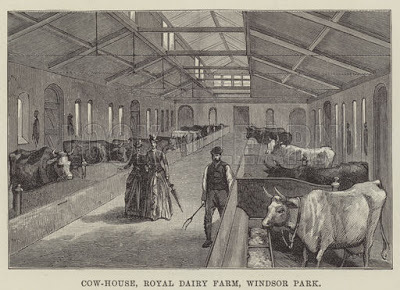

. . . . . . 'On a Sunday they only have a carriage or two for those who cannot walk. She (Queen Adelaide) never has her riding party, and often goes to the evening service; but she dedicated the time to us to show us her walks, flower-garden, a cottage that is building for her, her beautiful dairy, with a little neat country body like our Betty at the farm, and her

labourers' cottages, whence out came the children running to her. One had a kind word, another a pat on the head.

Copyright Look and Learn

Copyright Look and Learn'Then we saw the farmyard, pigs, cows, etc. Then she took us all over Frogmore Garden, which is extensive and very pretty, and then back by dairy and slopes. We were absolutely three hours, walking a good pace. We numbered about fourteen, but, with the usual thought, two carriages were at Frogmore to convey home the tired ones. Only two gave in. The day was very lovely, and her animation and spirits quite delightful. And this is our Queen--not an atom of pride or finery, yet dignified in the highest degree when necessary to be Majesty. God grant her peace and comfort may not be broke in upon!

Queen Adelaide by Sir David Wilkie

Queen Adelaide by Sir David Wilkie. . . . . 'Their Majesties are not seen till three o'clock. They breakfast and lunch in their private apartments. Then she comes out and arranges the morning excursions--all sorts of carriages and saddle-horses. She is a beautiful horse-woman, and rides about three hours, a good, merry pace. She sets forth with Maids of Honour and Ladies attendant, and generally returns surrounded by the gentlemen only, for it is understood she dispenses with their attendance the moment they get fatigued, and so they sneak off one by one. There are plenty of grooms to attend.

'Mrs. Clitherow got a quiet ride with my brother and the Duke of Dorset, whom the Queen always asks to meet us, as she always met him here in former times. Jane returned for the gentlemen to attend the Queen, and Jane and I went a long drive about the park with the

Princess Augusta, who was most chatty and good-humoured.

'On Sunday between church and luncheon we were summoned to the Queen's own apartment to present to her a picture of Bushey House. We have a young friend who has made a very pretty picture of old Boston House, and the happy thought of getting Bushey struck my brother. The Queen is so fond of Bushey! She looked some time at it, then turned to Jane and said, "I shall value it. You know how I love dear Bushey; but I value more the kind thought of having it painted for me." Jane told her when she became Queen her happiest days were past, and she often reminds her of it. She perpetually asks her questions, and says, "You are so honest; you tell me true." She draws extremely well. She took a likeness one evening of one of her beauties, Miss Bagot, and when she was showing her portfolio everyone exclaimed it was so very like.

'Poor Mrs. Kennedy Erskine[*] was there. She lived in her own apartments. Mrs. Fox,[**] her sister, and Miss Wilson took it by turns to dine with her. She was only married four years, was doatingly fond of her husband, and is left with three children.[***] The King went

every evening when he came from the dinner-room and sat half an hour with her. On his return to the drawing-room the Queen had taken her work and Jane Clitherow into the music-room, while I remained at her table with the Princess Augusta. The King came up. "Ah, my two Princesses Augusta, this is very comfortable; now to business.' She had

the official boxes, pen and ink all ready. He unlocked a box and set to work signing, the Princess rubbing them on the blotting-book and returning them into their cases. He signed seventy. Three times he was obliged to stop and put his hand in hot water, he had the cramp so severe in his fingers. When he signed the last he exclaimed, "Thank God, 'tis done!" He looked at me and said: "My dear madame, when I began signing I had 48,000 signatures my poor brother should have signed. I did them all, but I made a determination never to lay my head on my pillow till I had signed everything I ought on the day, cost me

what it might. It is cruel suffering, but, thank God! 'tis only cramp; my health never was better." The Queen was all attention, came and stood by him, but neither she nor the Princess said anything. When he is in pain he likes perfect quiet and to be left alone.

'On Monday morning all left the Castle, and the great square full of carriages being packed was most amusing. The Queen stood at the Window with us. There were three fours of the King's, and nineteen pair of post-horses, besides the out-riders, guard of honour, etc., etc.

'My paper makes me end, or I could go on till to-morrow. Adieu, my good friend! If I have amused you for a few minutes I am well repaid.

'My best remembrances to your trio.

'Yours truly, 'M. C.'

[*] The King's fourth daughter, Augusta, born 1803, married, first, 1827, Hon. John Kennedy Erskine--he died 1831; secondly, 1836, Lord Frederick Gordon.

[**] The King's second daughter, Mary; born 1798, married, 1824, Colonel C. R. Fox, A.D.C. to the Queen.

[***] As her four children are subsequently mentioned, it may be noted that a posthumous child was born two or three months after this letter was written.

PART TWO COMING SOON!

Published on January 07, 2017 00:00

Kristine Hughes's Blog

- Kristine Hughes's profile

- 6 followers

Kristine Hughes isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.