Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 53

December 3, 2016

LISTEN TO THE WATERLOO BUGLE BEING SOUNDED

Copyright Waterloo 200/Household Cavalry Museum

Copyright Waterloo 200/Household Cavalry MuseumIt is impossible to imagine the field at the Battle of Waterloo without calling the senses into play. The sights: soldiers clashing swords, horses rearing, men forming squares, columns of smoke from cannon fire. The smells: wet earth, sweat, wet horse and wet leather, cordite and black powder. The sounds: musket fire, swords singing metal on metal, horses neighing, men shouting and, perhaps most identifiable to us in the present day, bugles and trumpets sounding the calls. Amazingly, a few of the instruments that were played on the field of Battle at Waterloo have been preserved and are occasionally still played, like the trumpet above in the collection of the Household Cavalry Museum, which was played by John Edwards on the battlefield.

From the Waterloo200 website:

This field bugle was blown by 16-year-old John Edwards, who was duty trumpeter of the day. It sounded the charge for the Household Brigade which comprised the 1st and 2nd Life Guards, the Royal Horse Guards (the Blues) and the 1st Dragoon Guards.The other brigade, the Union Brigade, comprised the 1st (Royal) Dragoons, the Royal North British Dragoons (Scots Greys) and the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons. They charged a few minutes before the Household Brigade.The Allied cavalry manoeuvred through the ranks of Allied infantry and charged D’Erlon’s Corps, with its supporting cuirassiers, causing immense damage. Then, rather than turn back having successfully completed their task, they charged on over the French gun batteries. They arrived without support and with exhausted horses deep into the French lines, where they in turn suffered heavy casualties.Of the 2,500 cavalrymen involved, approximately half were killed or wounded. However, Napoleon had lost the initiative and failed to gain control of the battle. Two French Eagles (battalion colours) were taken.Trumpet or bugle calls were a vital command system in battles at this time. Shouting and screaming men and horses, the explosions of guns, cannon shells and small arms made verbal communication impossible. The smoke from black powder meant visibility was down to that of a thick fog. The incredible danger from musket balls, sabres, cannon balls and kicking horses made full attention vital. Only the sound of the trumpet was able to communicate between cavalry squadrons, each of which had a trumpeter.There were over 40 different bugle calls used in the field, all to command horses. Formations were controlled by calls known to the cavalrymen and made easier to remember by the addition of words in songbooks.The trumpet was played again at the Household Cavalry Musem during preparations for the 200th Anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo in 2015 and you can watch the video and listen to the call being played here. A far older sound recording of a Waterloo bugle was made in 1890 in London by trumpeter Landfried of the 17th Lancers, who is said to have played the charge at Balaclava using this Waterloo bugle. You can listen to that recording here.

For more on Martin Lanfried on the Lives of the Light Brigade site.

Walk the key sites connected to the Waterloo Battlefield with guide Ian Fletcher on Number One London's 1815: London to Waterloo Tour in June, 2017. In addition to the headquarters of both Wellington and Napoleon, we'll be visiting La Hay Sainte, Quatre Bras, Ligny, Hougoumont, the Lion's Mound, the newly remodeled Visitor's Centre and, of course, the Battlefield itself. At every stop, Ian will describe the events that took place there and explain their significance in the Allied victory. This is an opportunity you won't want to miss.

Published on December 03, 2016 23:00

November 30, 2016

ONCE AGAIN WEDNESDAY: MUDLARKING ON THE RIVER THAMES

Since there has been so much interest in my recent mudlarking adventures with my pal, author Sue Ellen Welfonder this past September, I thought I'd re-run my very first post on the subject, originally published July 1, 2010:

Since there has been so much interest in my recent mudlarking adventures with my pal, author Sue Ellen Welfonder this past September, I thought I'd re-run my very first post on the subject, originally published July 1, 2010:Many, many (many) years ago, when I first began doing research into London history, I was intrigued to learn about the Mudlarks of London, people from the poorer classes, typically children and the elderly, who scavenged along the banks of the River Thames at low tide looking for anything remotely valuable - clothing, coal, coins, pottery, items that had fallen off of ships and barges, etc etc. - that they could turn around and sell to the rag and bone man in order to earn enough for a meal. Mudlarking was considered to be lowest rung on the scavenger's ladder, so it was with great surprise, and a lot of pleasure, that I found myself actually mudlarking during my jaunt in London.

Having roamed the streets and gardens of London proper and venturing as far north as Hampstead and as far west as Windsor, my daughter, Brooke, and I turned our attention one day to the area of London south of the River - to Southwark, that once desperate area known for being the den of drunken sailors, thieves, prostitutes, cut throats and the Clink Prison - now a really tacky tourist trap.

As we were walking along the River on the Queen's Walk, a pedestrian promenade located on the South Bank of the River between Lambeth Bridge and Tower Bridge, we came upon stone steps leading down to the River. The tide was out, exposing what appeared to be a rocky beach of sorts. We made our way down and, uncertain as to whether or not we were actually allowed down there, tentatively began to walk towards the shore.

As we were walking along the River on the Queen's Walk, a pedestrian promenade located on the South Bank of the River between Lambeth Bridge and Tower Bridge, we came upon stone steps leading down to the River. The tide was out, exposing what appeared to be a rocky beach of sorts. We made our way down and, uncertain as to whether or not we were actually allowed down there, tentatively began to walk towards the shore.

You can see the usual high water mark from the algae line in the photo above. I stood there gazing at this rare view of the River with it's beach exposed, recalling all I'd read about the long ago mudlarks. As I looked at St. Paul's Cathedral on the distant shoreline, my heart skipped a beat as I realized that this was one of those moments I'd remember always - to be able to, for a moment, at a distance of centuries - walk in the mudlark's shoes, to see the River as they'd seen it, to feel, as they must have done, as though I were somewhere I shouldn't be, doing something I shouldn't be doing, but compelled to carry on.

As I was telling Brooke the tale of the mudlarks, I glanced down at the sand and saw a shard of blue and white pottery. Holding it up, I showed Brooke. Where had it come from, she asked. Who knows, said I (with infinite motherly wisdom). Honestly, it could have washed up last week or last century. Or two centuries ago. Before I knew it, I'd spied another shard, and another. I was off, while my daughter rolled her eyes, telling me that she couldn't believe I was actually garbage picking on the beach. Treasure hunting, I said, correcting her. I told her that many valuable objects were known to have washed up from the Thames - Medieval stuff, Restoration gee gaws, Georgian trash, even. As if to prove my point, at that moment I found a bone. Really. A dried out animal bone. Maybe the leg bone of a dog. Fascinated, Brooke stepped in for a closer look. Is it new? she asked. Nah, I replied sagely, look, the bone and the marrow are all dried out. What's it from? she asked. Some small animal, like a dog, I said as I gingerly let the bone fall to the sand. Of course, had the bone come complete with a tag that read "Authentic Leg Bone of a Regency Era Dog" I would have kept it, but the bone had done it's trick - now Brooke had gotten scavenger fever. For about an hour we combed the beach until I noted (again with great wisdom) that the tide was beginning to turn and come back in. By this time, I'd amassed a bagful of blue and white pottery shards, one of them complete with the full figure of a robed Oriental person. I will put these shards in a bowl at home, with a note beneath them that reads "Found on banks of Thames River June 2010" and will occasionally sift through each one and remember with great fondness the day I became a mudlark. Here's a photo of the sign above the bridge we were scavenging beneath -

Leaving the sand and returning to the streets of Southwark, Brooke and I came upon a pub called . . . The Mudlark (4 Montague Close, Southwark, London SE1 9DA). I later found out that today there's a London-based Society of Thames Mudlarks, who are granted a special license by the Port of London to excavate the beach and who must turn over finds of historic importance to the Museum of London, whose holdings include the Cheapside Hoard, an eye-popping collection of 400 pieces of Elizabethan and Jacobean jewelry, dating back to between 1560 and 1630. The hoard was probably buried in the early 17th century and discovered in 1912, by workmen digging in a cellar in the neighborhood of Cheapside. Which is why there are now lots of regulations surrounding mudlarking about which Brooke and I were blissfully unaware.

It seems that journalist Nick Curtis took to the sand by the Thames himself and wrote about his own mudlarking adventure in the London Evening Standard. Here's a portion of his article:

My day begins with the early morning low tide, in the mud of the foreshore near Custom House on the north bank near the Tower of London. Here, with commuters trudging above, I meet Ian Smith, a leading member of London's loose community of mudlarks. Ian deals in antiques but he's been combing the banks of the Thames for fun since the 1970s. When we meet, he's hip deep in a muddy hole.

Anyone can wander down to the foreshore and pick up objects from the surface, but you need a licence from the Port of London Authority to dig or to sift. “Treasure” is the property of the Crown, although, as Ian says, no one would ever deliberately conceal valuables on a silty tidal foreshore. Plus, things don't wash up from the river, they wash out from the land. Finds of historic interest are shown to the Port Antiquities Scheme's finds liaison officer and archaeologist Kate Sumnall and, ideally, donated or sold to the collection of the Museum of London, where she works. Ian once found a hoard of counterfeit George II coins, and has donated several exquisite medieval pewter badges — lucky charms or pilgrims' tokens — to the museum.

Even at first glance, there is tons of stuff on the shore. Victorian spikes, nails and barrel hoops, huge oyster shells and blackened animal bones and teeth. Once I've got my eye in, I also spot hundreds of clay pipe fragments. The smallest are the oldest, and were given away free in the 16th century with a tiny amount of the new and expensive import, tobacco. After just over an hour I've also found an ornate key, a stamped lead token, a pewter button and an iron flint striker for kindling fires.

Most of these are probably 17th or 18th century, but fragments of stoneware Bellarmine jars showing a bearded face — supposedly mocking an abstinent cardinal — might be from the 13th century. I'd love to search longer but time, and the Thames tide, wait for no mudlark.

Speaking of tides, Brooke and I stumbled upon the stairs at low tide, but if you want to plan your day around mudlarking, here's a link to the Thames Tides Table.

Published on November 30, 2016 01:01

November 27, 2016

THE BRIGHTON PAVILION - CAREME'S KITCHEN

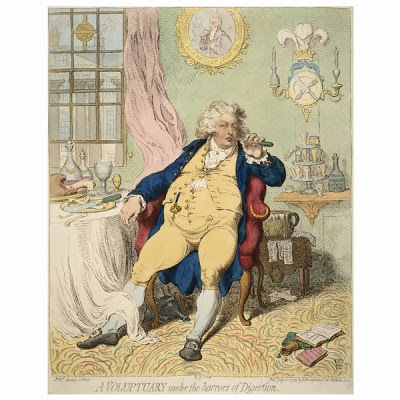

The Royal Pavilion at Brighton is a fanciful building reflecting the enigmatic character of the man for whom it was created, George, Prince of Wales, the Prince Regent from 1811-1820 and King George IV from 1820 to his death in 1830. Prinny, as he was often known, considered himself "The First Gentleman of Europe," and a connoisseur of all things tasteful and refined. And that was the paradox: He did indeed have good taste but he carried things to the extremes of excess.

James Gillray: A Voluptuary under the Horrors of Digestion, 1792The British Museum

James Gillray: A Voluptuary under the Horrors of Digestion, 1792The British MuseumThe Great Kitchen at the Pavilion was built especially for the Prince's chefs who kept him and his minions well fed and produced brilliant banquets for his royal guests.

(©Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton and Hove)

The Prince Regent was obsessed with all things French: architecture, décor, furniture, china, fashion, and "above all" French food. Once Great Britain had driven out Napoleon, the Prince Regent had to have a French Chef to prepare his meals and banquets in London at Carlton House and at his Brighton home, the Royal Pavilion. He sent his household Clerk Controller to Paris to find a chef. Even the Prince was surprised when the celebrated Antonin Carême agreed to come, probably for the offer of a very high salary. Carême had prepared elaborate meals for the notables of Napoleonic France, particularly the diplomat Talleyrand and the Emperor himself - Carême was the first "celebrity chef."

Cooking for Kings: The Life of Antonin Carême, the First Celebrity Chefby Ian Kelly, a biography with recipes, 2003

Cooking for Kings: The Life of Antonin Carême, the First Celebrity Chefby Ian Kelly, a biography with recipes, 2003Distinguished British writer and actor Ian Kelly is the author of Carême's biography. You can read more about Ian and his books here. A chapter is devoted to Carême's brief but notable career in England. He arrived in July 1816, having left his wife and child in Paris. Carême certainly impressed the Prince's guests with his dishes, particularly with his elaborate, even ostentatious, confections, up to four feet tall.

Before Carême arrived, the Prince was already grossly overweight. Supposedly the Prince said that the temptations of his new chef's cooking would be the death of him. Carême replied, "Your highness, my concern is to tempt your appetite; yours is to curb it." Touché!

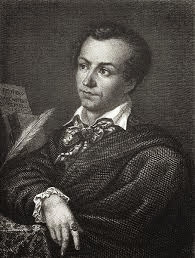

Marie-Antoine Carême (1784-1833)

Marie-Antoine Carême (1784-1833)Kelly had access to the records in the Royal Archive which include bills and notes from Careme's time. When he arrived from France, Carême altered the usual method of disposing of the extra food not eaten at the royal table. Previously, the staff could sell leftovers, plus such things as candles, and share the profits. Carême kept for himself the right to dispose of items from the kitchens. Thus he was quite unpopular with the staff. Kelly tells some wonderful stories about the conflicts. In late 1817, Carême returned to France.

(©Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton and Hove)

(©Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton and Hove)The kitchen as it appears today is only a part of the many rooms that were once used as bakeries, for supplies, preparation, sculleries, and so forth. Kelly found records showing in 1817, in one month, the kitchens took supply of 428 bunches of radishes, 153 Savoy Cabbages, 7 dozen Cos lettuces, and spent over £250 on 1,854 pounds of beef and similar amounts of mutton and veal.

For a 360-degree view of the kitchen, click here.

The Great Kitchen was built as part of the remodeling of the Marine Pavilion by architect John Nash. Intended to be a model of innovation, the kitchen had running water, steam heating and special ventilation through the high windows. The oriental theme used in varied versions throughout the palace is also found in the kitchen. Tall pillars supporting the ceiling are adorned with copper palm fronds.

Nash water-colour of the Great Kitchen, 1828

Nash water-colour of the Great Kitchen, 1828The kitchen has been extensively renovated and visitors can see an impressive collection of of Regency-era and early Victorian kitchen equipment. Some of the copper pots on display once belonged to Apsley House, the London residence of the Duke of Wellington.

In his excellent book, Ian Kelly reproduces the menu of 18 January, 1817, for a dinner for Grand Duke Nicholas of Russia: eight soups, eight releves de Poisson, fifteen Assiettes Volantes, eight grosses pieces, forty entrees, eight pieces montees, eight roasts and thirty-two entremets." Kelly writes, "the banquet was to be seen and experienced as part of the theater of international relations -- Napoleon's chef creating a gastronomic spectacle for the conquering British monarch and his Russian allies." Excess indeed.

Kelly's conclusion is that Carême's "...genius was to deploy methods that brought out the natural flavors of food to create a gourmand's paradise while at the same time producing a feast which would, visually live up to the most opulent settings." He would have been the superstar of the cable Food Channels!

More information on the Royal Kitchen can be found here.

Both Brighton and the Royal Pavilion are included on the itineraries for Number One London's 2017 Regency Tour and Queen Victoria Tour. Details at links.

Published on November 27, 2016 00:00

November 22, 2016

ONCE AGAIN WEDNESDAY: VICTORIA & ALBERT - ART & LOVE

Today's Once Again Wednesday post was originally published in July, 2010 and features my visit with Victoria to see the Victoria & Albert Art & Love Exhibit at the Queen's Gallery in London. To this day, it remains the single best exhibition I've ever attended. So many truly iconic pieces of art in one room, never mind one exhibition. Do click through and read our original post.

Next, follow this link to view the 19 page catalogue from the Exhibition which focused on Queen Victoria's personal jewelry. Lot's of historical details and little known facts, including mention of the Duke of Wellington.

Published on November 22, 2016 23:30

November 20, 2016

THE CHATSWORTH SHEEP

Is there anything more English than sheep? I don't think so. Diane Perkins doesn't think so. I know that because between the two of us, she and I must have taken at least 400 photos of sheep during our two weeks in England this past May. Forget Big Ben, the Union Jack or red telephone boxes - sheep are the quintessential symbol of England.

And Diane and I were lucky enough to be in England during the lambing season. We stayed at The Cavendish Hotel (above) on the Chatsworth Estate in Baslow, Derbyshire, where, it transpired happily, the window in our room looked out over the fields - fields that were chock full of sheep.

The sheep baaahhhed, or bleated, constantly. They bleated morning, noon and night. We woke up to the sound of sheep and we fell asleep to the sound of sheep. Diane and I soon realized that our lives had not previously been complete, having lacked the sound sheep.

At first glance, you may think that the photos above and below are the same, but look again. See how the sheep at the bottom of the second photo are closer together? Which begged a second photo? Not to mention a fifth? You begin to see how it's possible for one to take hundreds of photos of sheep.

After a few days at Chatsworth, I became convinced that sheep were the secret to a happy life. I am seriously consdering renting one of the Chatsworth cottages for lambing season next year. They even have days when you can sign up to be driven into the fields in the hopes of witnessing a birth. Heaven!

The Russian Cottage at Chatsworth

Jean-Honoré Fragonard - The Shepherdess/Milwaukee Art Museum

Jean-Honoré Fragonard - The Shepherdess/Milwaukee Art MuseumI begin to understand why Marie Antoinette found the idea of playing at being a shepherdess so alluring. You will find below just a few of the many sheep photos I took at Chatsworth.

Snap, snap, snap, step, step . . . . . . snap, step, step . . . . . Diane and I walked the paths and snapped photos, each lost in our worlds, for quite some time. We were walking our way over the crest, towards Edensor, the village that the 6th Duke of Devonshire, the Bachelor Duke, had dismantled and reconstructed to his design circa 1840. Up till this point, all of the sheep we'd seen had been a fair distance from the path we were walking on. If they appear any closer, it's because I used the zoom.

However, as soon as we crested the slight incline, I came face to face with the sheep below.

It was right there. A foot off the walking path. And it was big. And, in a weird way, intimidating. I stopped short and it wasn't long before Diane, still snapping pictures, bumped into my back. She looked up and saw what I saw, the sheep pictured above and below. Big, shaggy and completely owning it's space.

"Don't make eye contact!" Diane warned.

"What?!"

"Don't make eye contact," Diane repeated.

"It's a sheep."

"It's a big sheep. With babies. And don't tell me you're not scared of it."

"Well, I was scared of it, but on second thought, what can it do to us? I mean, it doesn't even have horns."

"No but it's got hooves and teeth and it weighs almost as much as we do. And it's got babies to protect. I don't know what it could do to us, and I don't want to find out. Don't make eye contact!"

Reasoning that I had another week and a half in England still ahead of me, I decided not to take chances with my life. I looked away and we hot footed it down the lane and across the road to Edensor.

Where we found the sign below on the village gate.

"Do you think we worried them?" Diane asked.

"More the other way round, no?" I responded. We turned away and attempted to find our objectives - the graves of Kick Kennedy and Deborah, the recently departed Duchess of Devonshire.

As we approached the graveyard by the church, we spotted a wondrous sight - newly shorn sheep set to graze within the graveyard fence, thus keeping the cemetery all neat and tidy.

These sheep largely ignored us and kept their heads bent to the task at hand. Or hoof. When they did look our way, it was with curiosity and/or a sort of benign benevelance. Our faith in sheep was soon restored!

That night, we once again listened to the soothing sound of the sheep in the fields below our window. You've no idea how hard it is to fall asleep whilst counting sheep when one is actively avoiding making eye contact with them.

You can see the Chatsworth sheep live and in person when we visit the House, gardens and Edensor during Number One London's 2017 Country House Tour - full details can be found here.

Published on November 20, 2016 00:00

November 16, 2016

ONCE AGAIN WEDNESDAY: TRAVELS WITH VICTORIA: VISITING JOSEPHINE BONAPARTE'S MALMAISON

Originally published October 3, 2014

I recently had a free day in Paris and talked my husband Ed into accompanying me to visit the Chateau de Malmaison in the town of Rueil-Malmaison, about seven miles outside the city.

I recently had a free day in Paris and talked my husband Ed into accompanying me to visit the Chateau de Malmaison in the town of Rueil-Malmaison, about seven miles outside the city.

Josephine's portraits in the Emperor's Apartment

Josephine's portraits in the Emperor's Apartment

Josephine in 1806, by Henri-Francois RiesenerJosephine purchased the chateau (built in the 17thCentury) in 1799 and used it as her retreat from the rigors of life as the eventual Empress of France in the Tuileries Palace. In this charming country house, she could cultivate her roses and enjoy peaceful solitude or host intimate soirees and picnics with chosen guests.

Josephine in 1806, by Henri-Francois RiesenerJosephine purchased the chateau (built in the 17thCentury) in 1799 and used it as her retreat from the rigors of life as the eventual Empress of France in the Tuileries Palace. In this charming country house, she could cultivate her roses and enjoy peaceful solitude or host intimate soirees and picnics with chosen guests.

The Entrance Hall

The Entrance Hall

Josephine was born on the Caribbean island of Martinique, June 23, 1763, named Marie-Joseph-Rose de Tascher de la Pagerie. She grew up among the sugar plantation society on the island At age seventeen, she went to Paris for an arranged marriage to Count Alexandre de Beauharnais. With him she had two children, a son, Eugene de Beauharnais (1781-1824) and a daughter, Hortense (1783-1837). Imprisoned during the Revolution, the Count was guillotined in 1794, but Josephine was released.

The Billiard Room

The Billiard Room

When she met the young officer Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), he fell madly in love with her. Until he renamed her Josephine, she was known as Rose. They married in 1796. In December 1804, in the Cathedral of Notre Dame, Paris, Napoleon crowned himself Emperor and Josephine Empress of France, in the presence of the Court and the Pope.

Le Salon Doré

Le Salon Doré

Unable to bear any more children, Josephine reluctantly agreed to separation and divorce. In December 1809, she moved permanently to Malmaison.

The Music Room

The Music Room

Josephine's Harp and Pianoforte

Josephine's Harp and Pianoforte

Napoleon married Marie Louise, daughter of Austrian Emperor Francis I, and a year later, in 1811, his only legitimate child was born. He was named Napoleon, designated the King of Rome. [This unfortunate young man, so greatly anticipated, died in his early 20’s.]

Dining Room

Dining Room

In April, 1814, Napoleon abdicated, turning Paris over to the Allied Powers of Europe and Britain, and going into exile on Elba. In May of 1814, Josephine died at Malmaison, of pneumonia, which developed from a cold she caught while walking in her garden with the Russian Tsar Alexander, one of the victorious allies in the first defeat of Napoleon.

La Salle du Conseil (Council Room)

La Salle du Conseil (Council Room)

Portrait of Thomas Jefferson, in the Council Room

Portrait of Thomas Jefferson, in the Council Room

Napoleon, though not always faithful to Josephine, remained attached to her for the rest of his life, even through his divorce and re-marriage. After her death and before his final exile to St. Helena, Napoleon returned to Malmaison for a farewell visit.

La Bibliothéque (The Library)

La Bibliothéque (The Library)

By her first husband, Josephine was the grandmother of Napoleon III, son of her daughter. She is also an ancestress of numerous European Royals.

So far, all my pictures were taken in rooms on the ground floor of the house, all with doors opening into the gardens. Upstairs were the private chambers of Napoleon and Josephine each with their own apartments, i.e. suites of rooms.

two angles on Le Salon de l'Empereur

two angles on Le Salon de l'Empereur

La chamber à coucher de l'Empereur

La chamber à coucher de l'Empereur

Napoleon's shaving stand

Napoleon's shaving stand

The two personal apartments are divided by rooms containing treasures the couple accumulated.

Ceremonial Swords

Ceremonial Swords

A version of David's Napoleon Crossing the Great Saint-Bernard Pass

A version of David's Napoleon Crossing the Great Saint-Bernard Pass

Josephine's gold table serviceThe suite of rooms belonging to Josephine begins with a sitting room filled with red velvet and gilt chairs with white swan armrests, unique in my experience, Not even the Prince Regent had these! I can only assume that he never heard of them.

Josephine's gold table serviceThe suite of rooms belonging to Josephine begins with a sitting room filled with red velvet and gilt chairs with white swan armrests, unique in my experience, Not even the Prince Regent had these! I can only assume that he never heard of them.

Three Views of the Frieze Room, named for the Greco-Roman frieze, also featuring swans

Three Views of the Frieze Room, named for the Greco-Roman frieze, also featuring swans

La chambre à coucher de l'Impératrice

La chambre à coucher de l'Impératrice

Note the Swan theme continues.

Washstand of Mahogany and Sèvres porcelainNext to the tented bedroom is another bedroom, known as La chamber ordinaire de l'Impératrice and Le Cabinet a toilette.

Washstand of Mahogany and Sèvres porcelainNext to the tented bedroom is another bedroom, known as La chamber ordinaire de l'Impératrice and Le Cabinet a toilette.

After Josephine’s death, son Eugene lived at Malmaison; later it was sold several times before being presented as a gift to the nation of France by Daniel Iffla (known as Osiris), art enthusiast and philanthropist, whose collections can be seen in a small museum on the chateau’s grounds.

More soon on Malmaison's gardens.

More soon on Malmaison's gardens.

If you want to visit, allow about 90 minutes each way on the Metro (to La Defense) and by bus. Malmaison is currently closed on Tuesdays.

I recently had a free day in Paris and talked my husband Ed into accompanying me to visit the Chateau de Malmaison in the town of Rueil-Malmaison, about seven miles outside the city.

I recently had a free day in Paris and talked my husband Ed into accompanying me to visit the Chateau de Malmaison in the town of Rueil-Malmaison, about seven miles outside the city.

Josephine's portraits in the Emperor's Apartment

Josephine's portraits in the Emperor's Apartment Josephine in 1806, by Henri-Francois RiesenerJosephine purchased the chateau (built in the 17thCentury) in 1799 and used it as her retreat from the rigors of life as the eventual Empress of France in the Tuileries Palace. In this charming country house, she could cultivate her roses and enjoy peaceful solitude or host intimate soirees and picnics with chosen guests.

Josephine in 1806, by Henri-Francois RiesenerJosephine purchased the chateau (built in the 17thCentury) in 1799 and used it as her retreat from the rigors of life as the eventual Empress of France in the Tuileries Palace. In this charming country house, she could cultivate her roses and enjoy peaceful solitude or host intimate soirees and picnics with chosen guests.

The Entrance Hall

The Entrance HallJosephine was born on the Caribbean island of Martinique, June 23, 1763, named Marie-Joseph-Rose de Tascher de la Pagerie. She grew up among the sugar plantation society on the island At age seventeen, she went to Paris for an arranged marriage to Count Alexandre de Beauharnais. With him she had two children, a son, Eugene de Beauharnais (1781-1824) and a daughter, Hortense (1783-1837). Imprisoned during the Revolution, the Count was guillotined in 1794, but Josephine was released.

The Billiard Room

The Billiard RoomWhen she met the young officer Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), he fell madly in love with her. Until he renamed her Josephine, she was known as Rose. They married in 1796. In December 1804, in the Cathedral of Notre Dame, Paris, Napoleon crowned himself Emperor and Josephine Empress of France, in the presence of the Court and the Pope.

Le Salon Doré

Le Salon DoréUnable to bear any more children, Josephine reluctantly agreed to separation and divorce. In December 1809, she moved permanently to Malmaison.

The Music Room

The Music Room Josephine's Harp and Pianoforte

Josephine's Harp and PianoforteNapoleon married Marie Louise, daughter of Austrian Emperor Francis I, and a year later, in 1811, his only legitimate child was born. He was named Napoleon, designated the King of Rome. [This unfortunate young man, so greatly anticipated, died in his early 20’s.]

Dining Room

Dining RoomIn April, 1814, Napoleon abdicated, turning Paris over to the Allied Powers of Europe and Britain, and going into exile on Elba. In May of 1814, Josephine died at Malmaison, of pneumonia, which developed from a cold she caught while walking in her garden with the Russian Tsar Alexander, one of the victorious allies in the first defeat of Napoleon.

La Salle du Conseil (Council Room)

La Salle du Conseil (Council Room) Portrait of Thomas Jefferson, in the Council Room

Portrait of Thomas Jefferson, in the Council RoomNapoleon, though not always faithful to Josephine, remained attached to her for the rest of his life, even through his divorce and re-marriage. After her death and before his final exile to St. Helena, Napoleon returned to Malmaison for a farewell visit.

La Bibliothéque (The Library)

La Bibliothéque (The Library)By her first husband, Josephine was the grandmother of Napoleon III, son of her daughter. She is also an ancestress of numerous European Royals.

So far, all my pictures were taken in rooms on the ground floor of the house, all with doors opening into the gardens. Upstairs were the private chambers of Napoleon and Josephine each with their own apartments, i.e. suites of rooms.

two angles on Le Salon de l'Empereur

two angles on Le Salon de l'Empereur La chamber à coucher de l'Empereur

La chamber à coucher de l'Empereur Napoleon's shaving stand

Napoleon's shaving standThe two personal apartments are divided by rooms containing treasures the couple accumulated.

Ceremonial Swords

Ceremonial Swords A version of David's Napoleon Crossing the Great Saint-Bernard Pass

A version of David's Napoleon Crossing the Great Saint-Bernard Pass Josephine's gold table serviceThe suite of rooms belonging to Josephine begins with a sitting room filled with red velvet and gilt chairs with white swan armrests, unique in my experience, Not even the Prince Regent had these! I can only assume that he never heard of them.

Josephine's gold table serviceThe suite of rooms belonging to Josephine begins with a sitting room filled with red velvet and gilt chairs with white swan armrests, unique in my experience, Not even the Prince Regent had these! I can only assume that he never heard of them.

Three Views of the Frieze Room, named for the Greco-Roman frieze, also featuring swans

Three Views of the Frieze Room, named for the Greco-Roman frieze, also featuring swans  La chambre à coucher de l'Impératrice

La chambre à coucher de l'ImpératriceNote the Swan theme continues.

Washstand of Mahogany and Sèvres porcelainNext to the tented bedroom is another bedroom, known as La chamber ordinaire de l'Impératrice and Le Cabinet a toilette.

Washstand of Mahogany and Sèvres porcelainNext to the tented bedroom is another bedroom, known as La chamber ordinaire de l'Impératrice and Le Cabinet a toilette.

After Josephine’s death, son Eugene lived at Malmaison; later it was sold several times before being presented as a gift to the nation of France by Daniel Iffla (known as Osiris), art enthusiast and philanthropist, whose collections can be seen in a small museum on the chateau’s grounds.

More soon on Malmaison's gardens.

More soon on Malmaison's gardens.If you want to visit, allow about 90 minutes each way on the Metro (to La Defense) and by bus. Malmaison is currently closed on Tuesdays.

Published on November 16, 2016 00:30

November 11, 2016

A TOUR GUIDE IN ENGLAND: DAY 6 PART THREE - WHAT WE SAW IN THE CHATSWORTH GARDENS

The Gardens at Chatsworth House are extensive, to say the least. There are 105 acres of gardens and they are full of surprises, with waterworks, sculptures, the maze and a wide variety of plants on show. The gardens have been evolving for the past 450 years, with the Bachelor Duke and Joseph Paxton perhaps having had the largest, surely the costliest, influence on the grounds. In 1811 the 6th Duke (known as the Bachelor Duke) inherited a neglected and fifteen years passed before Joseph Paxton was appointed as head gardener. Paxton proved to be the most innovative garden designer of his era, and remains the greatest single influence on Chatsworth’s garden.

In addition to the 300 year old Cascade, the Gardens include the gravity-fed Emperor Fountain, above. In 1844, it became known that Czar Nicholas, Emperor of Russia might visit Chatsworth. The Duke thought to welcome the Czar with an even higher fountain than the one at Peterhof (the Czar’s palace in N.E. Russia), and so an existing fountain was renovated. Unfortunately, the Czar never visited Chatsworth, but the new fountain was still named after him.

Above and below are photos of Blanche's Vase, on the Long Walk, named for Blanche Georgiana Cavendish, nee Howard, granddaughter of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. Blanche married William Cavendish, 2nd Earl of Burlington, but tragically died at the age of 28 in 1840. Her uncle, the Duke of Devonshire, was left heartbroken by the death of his favorite niece and wrote the following: "There are many things at Chatsworth that I should not have allowed myself to do had I not reposed in the thoughts of being succeeded by a person so indulgent, so much attached to me as Blanche." ('The Garden at Chatsworth' by Deborah, Duchess of Devonshire).

The latest restoration project at the Gardens has been conducted on the Trout Stream. You'll find a short video on the project here.

We'll be spending an entire day exploring the Chatsworth gardens during Number One London's 2017 Country House Tour. Our estate guide will share the hidden stories and history of the gardens, including the famed glasshouses built by Joseph Paxton, and a picnic lunch will be served in the gardens. You'll find complete tour details here.

Published on November 11, 2016 23:30

November 9, 2016

ONCE AGAIN WEDNESDAY: DO YOU KNOW ABOUT MONARCH OF THE GLEN?

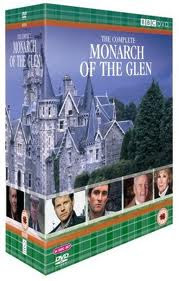

No, not that Monarch of the Glen.

This Monarch of the Glen.

Monarch of the Glen was a BBC TV drama series featuring the exploits of an impecunious and somewhat dysfunctional Highland family in their efforts to keep the estate of Glenbogle going after Archie MacDonald, a young restaurateur, is called back to his childhood home where he must act as the new Laird.

Adapted from the so-called "Highland" novels of Compton MacKenzie, author of Sylvia Scarlett, the series originally starred Richard Briers, Susan Hampshire, Hamish Clark, Alastair Mackenzie, Dawn Steele and Sandy Morton. The programme ran for seven series, from 2000 to 2006, becoming the longest running non-soap drama ever run by the BBC, beating Ballykissangel by one year.

Adapted from the so-called "Highland" novels of Compton MacKenzie, author of Sylvia Scarlett, the series originally starred Richard Briers, Susan Hampshire, Hamish Clark, Alastair Mackenzie, Dawn Steele and Sandy Morton. The programme ran for seven series, from 2000 to 2006, becoming the longest running non-soap drama ever run by the BBC, beating Ballykissangel by one year.  In reality, Archie is not really the new Laird, as his eccentric father, Hector, is still alive, though increasingly unable, or unwilling, to fulfill the role. Archie's mother, Molly (Susan Hampshire, right) uses this as a crafty excuse to call her son home. In the first season, Archie resents his obligations as various problems arise at Glenbogle - not the least of which is that Hector's neglect of the estate has put it in dire financial straights. As the episodes progress, Archie finds himself increasingly attached to both the estate and it's inhabitants, including Lexie (Dawn Steele), the estate's sexy, street-smart cook; the shy and bumbling kilt-wearing handyman Duncan (Hamish Clark), and a quintessentially Scots gilly named Golly (Alexander Morton). Archie is constantly tasked with making the estate profitable, or at least marginally solvent, and schemes for raising money include turning the estate into a museum, a wedding hall, a hotel and a wildlife park. As the series goes on, we learn more about the lives of these characters, their connections to one another and their own reasons for wanting Glenbogle, and Archie, to succeed.

In reality, Archie is not really the new Laird, as his eccentric father, Hector, is still alive, though increasingly unable, or unwilling, to fulfill the role. Archie's mother, Molly (Susan Hampshire, right) uses this as a crafty excuse to call her son home. In the first season, Archie resents his obligations as various problems arise at Glenbogle - not the least of which is that Hector's neglect of the estate has put it in dire financial straights. As the episodes progress, Archie finds himself increasingly attached to both the estate and it's inhabitants, including Lexie (Dawn Steele), the estate's sexy, street-smart cook; the shy and bumbling kilt-wearing handyman Duncan (Hamish Clark), and a quintessentially Scots gilly named Golly (Alexander Morton). Archie is constantly tasked with making the estate profitable, or at least marginally solvent, and schemes for raising money include turning the estate into a museum, a wedding hall, a hotel and a wildlife park. As the series goes on, we learn more about the lives of these characters, their connections to one another and their own reasons for wanting Glenbogle, and Archie, to succeed.  Another of the stars of Monarch of the Glen is the atmospheric setting and gorgeous Highland scenery. The series was filmed around Badenoch and Strathspey - mainly in the Laggan, Newtonmore and Kingussie area, and the fairy-tale like Ardverikie House, on the far shore of Loch Laggan, became Glenbogle Castle. Ardverikie is itself a grand Scottish estate which, through time, has faced many of the problems that underpinned the stories of the dramatized in the series.

Another of the stars of Monarch of the Glen is the atmospheric setting and gorgeous Highland scenery. The series was filmed around Badenoch and Strathspey - mainly in the Laggan, Newtonmore and Kingussie area, and the fairy-tale like Ardverikie House, on the far shore of Loch Laggan, became Glenbogle Castle. Ardverikie is itself a grand Scottish estate which, through time, has faced many of the problems that underpinned the stories of the dramatized in the series.Ardverikie was built in 1878 by local craftsmen and has been owned by the same family since then. It has had a rich history, almost chosen by Queen Victoria instead of Balmoral as her Scottish retreat and ironically used briefly in the film `Mrs Brown' for some scenes. English painter John Millais spent many months here on the estate sketching and drawing. Landseer's influence is also evident within the house, as well as in the adoption of his most famous stag painting for the title of the television series.

You can watch a bit of Monarch of the Glen here, but the series is widely available through Netflix and local libraries.

If you've always dreamed of seeing the Highlands for yourself, consider joining author and guide Sue Ellen Welfonder for Number One London's 2017 Scottish Castles Tour - details can be found here. We'd love to share our love of Scotland with you!

Published on November 09, 2016 00:00

November 3, 2016

A TOUR GUIDE IN ENGLAND: CHATSWORTH - THE PORTRAITS

Diane Gaston (Perkins) and I spent two entire days at Chatsworth House last May and we honestly could have gone back for a third. It's that sort of House - you can't help but to want more helpings of it. One of the many draws to Chatsworth is the vast collection of portraits on show. In this post, we concentrate on the ladies, more specifically, on the Duchesses of Devonshire. It was stunning to see many of the most iconic portraits of the Duchesses on show. All in one place. At the same time.

Above, Diane is admiring the portrait of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire as Cynthia, from Spenser's 'The Faerie Queene,' painted by artist Maria Cosway in 1783. Further down the same wall, in the same room, we found the arrangement of portraits below.

The portrait at the centre of this grouping is Gainesborough's famous depiction of Georgiana. It is the most identifiable and not only because it is a masterly work of art - the portrait itself has a twisting, criminal history. You can read all about it in a past post here.

Above, Georgiana as painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds circa 1780

Above is Reynold's portrait of Lady Elizabeth Foster, Georgiana's friend and confidante, who went on to herself become the Duchess of Devonshire after Georgiana's death. You can read the entire story in a post on Catherine Curzon's blog here.

Which brings us to another group of portraits at Chatsworth House, executed in an entirely, some might say startlingly, different style.

Painted by artist Lucian Freud, a family friend, this collection includes more recent members of the Cavendish family, including Deborah (nee Mitford), Duchess of Devonshire.

If her willingness to sit for an artist with such a raw, frank and unflattering way of approaching his subjects is anything to go by, Debo hadn't a narcissistic bone in her body.

As you may or may not already know, I have a special place in my heart for Deborah Mitford. I have to be honest and say that I much prefer to see her depicted in a more conventional style.

This gorgeous portrait of Deborah by Pietro Annigoni (1954) can also be seen at Chatsworth House.

Diane and I were fortunate to be able to also view an exhibition of 65 of Cecil Beaton's portraits of Deborah and her family and friends at Chatsworth. The exhibition is aptly titled Never a Bore: The Duchess of Devonshire and Her Set and runs through 3 January, 2017. Included are both candid and posed photographs, such as this portrait, a personal favourite. In fact, I like it so well that I've made it my Facebook photo.

You can read The Telegraph's story on the entire Beaton exhibition here.

We will be spending two days at Chatsworth House during The Country House Tour in 2017. Please click here for details.

Published on November 03, 2016 23:30

November 1, 2016

NUMBER ONE LONDON TOURS HAS ARRIVED!

It is with great pleasure that we announce the launch of Number One London Tours. The photo above was taken in May at the legendary restaurant, Simpson's in the Strand, London, where a few of the people involved in our tours gathered for a working dinner. From left: Diane Perkins/Gaston, Kristine Hughes Patrone, Ian Fletcher, Nicola Cornick and Melanie Hilton/Louise Allen.

2017 Tours

1815: London to Waterloo

The Regency Tour

A Week at the Lake

The Queen Victoria Tour

A Stay in the Cotswolds

The Country House Tour

The Scottish Castles Tour

Enter the Tour website here

Published on November 01, 2016 00:30

Kristine Hughes's Blog

- Kristine Hughes's profile

- 6 followers

Kristine Hughes isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.