Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 57

July 15, 2016

A TOUR GUIDE IN ENGLAND: DAY 2 - PART 3

After our visit to the National Portrait Gallery, Diane and I once more decided to wander aimlessly through our favourite City. We soon came across Godwin's Court, above, located off of St. Martin's Lane. Built around 1630, it was originally called Fisher's Alley and lately, it stood in as Knockturn Alley in the Harry Potter films. Coincidentally, Cecil Court, where Diane and I visited Mark Sullivan Antiques earlier in the day, stood in for Daigon Alley in the films, as well.

But Godwin's Court is not a film set, it exists as you see it above day in and day out, which is what I love about London. There are pockets of centuries old history to be found almost around every corner, if one knows where to look. See the sign below.

Above is Seven Dials, once one of the worst areas of London and a true rookery and one that Dickens was familiar with. Seven streets intersect here, warehouses abounded and many of the taverns had interconnecting basements through which thieves and ne'er do wells could escape the clutches of the law, such as it was in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Above and below, further peeks into the City's 18th century past.

After a while, we found ourselves in Charing Cross Road and in the same block as the few remaining antiquarian and second hand bookshops that survive here. When writing blog posts, I often forget that people I do not know, people who are younger than myself and people who haven't been to London may be reading my posts. I assume that others know as much about the things I write about as I do, and so I often forget to include bits of history or back stories to the places I feature. I do not want to do that here. This I must tell you - if you haven't read a book called 84 Charing Cross Road, you must rectify that immediately. Set just after WWII, the book covers the relationship in letters between a bookseller in London and a customer in New York who places requests for books via mail. There is also a movie of the same title starring Anthony Hopkins and Ann Bancroft which you are perfectly free to watch, but I urge you to read the book first and see the film afterwards, rather than watching it instead of reading the book.

After a good browse, during which I found but a single title and that for my mate Ian Fletcher, rather than for myself, we continued our stroll.

The entrance to The Ivy restaurant above and the stage door of the St. Martins Theatre, below.

Neither of us having seen The Mousetrap before, Diane and I decided to take in a performance and it was a hoot - a murder mystery set in an isolated English country house sometime in the 1940's, Agatha Christie's Mousetrap is the longest running play in history. Afterwards, we returned to our hotel for dinner and indulged in ribeye steaks, chips and pinot noir. The perfect end to a truly perfect day.

Day Three Coming Soon!

Published on July 15, 2016 23:00

July 13, 2016

ONCE AGAIN WEDNESDAY - Mr. Phillips's Auction Offices - Part Two

As we have seen in the previous post on this topic, Phillips's royal connections were impressive, but one of the Phillips auctions that has gone into the annals of London social history is that of the contents of Gore House and the belongings of its occupants, Lady Blessington (at right) and Count D'Orsay. The Times of Monday May 7,1849 tells the story. On page sixteen at the head of the fourth column are two advertisements, in the first of which Mr. Phillips of 73 New Bond Street offers for sale by auction ' the improved lease of the capital mansion ' known as Gore House' (a full description of the property follows); in the second 'Mr. Phillips begs 'to announce that he is honoured with instructions from the Right Hon. the Countess of Blessington (retiring to the continent) to submit to ' sale by auction, this day May 7, and 12 subsequent days, at 1 precisely each day, the splendid ' Furniture, costly jewels, and recherche Property ' contained in the above mansion,' and so forth, and so forth, to the extent of some eighteen or twenty lines.

As we have seen in the previous post on this topic, Phillips's royal connections were impressive, but one of the Phillips auctions that has gone into the annals of London social history is that of the contents of Gore House and the belongings of its occupants, Lady Blessington (at right) and Count D'Orsay. The Times of Monday May 7,1849 tells the story. On page sixteen at the head of the fourth column are two advertisements, in the first of which Mr. Phillips of 73 New Bond Street offers for sale by auction ' the improved lease of the capital mansion ' known as Gore House' (a full description of the property follows); in the second 'Mr. Phillips begs 'to announce that he is honoured with instructions from the Right Hon. the Countess of Blessington (retiring to the continent) to submit to ' sale by auction, this day May 7, and 12 subsequent days, at 1 precisely each day, the splendid ' Furniture, costly jewels, and recherche Property ' contained in the above mansion,' and so forth, and so forth, to the extent of some eighteen or twenty lines.During the three days prior to the sale 'twenty 'thousand persons' are said to have visited the house; the estimate seems large. Thackeray wrote Mrs. Brookfield that he had 'just come away from a dismal sight; Gore House 'full of snobs looking at the furniture.' There were present a number of 'odious bombazine ' women' whom he particularly hated. Also brutes who kept their hats on in the kind old drawingroom ; ' I longed to knock some of them off, and 'say, " Sir, be civil in a lady's room."' A French valet who had been left in charge, and with whom Thackeray talked a little, saw tears in the great novelist's eyes. Thackeray confessed to Mrs. Brookfield that his heart so melted toward the poor man that he had to give him a pound; the heart in question was always melting, and the purse was invariably affected.

In his Literary Life and Correspondence of the Countess of Blessington, Richard Robert Madden, a close friend of the Count and Countess, provides the following description of the sale:

In April, 1849, the clamours and importunate demands of Lady Blessington's creditors harassed her, and made it evident that an inevitable crash was coming. She had given bills to her bankers, and her bond likewise, for various advances, in anticipation of her jointure, to an amount approaching to £1500. Immediately after the sale, the bankers acknowledged having received from Mr. Phillips, the auctioneer, by her order, the sum of £1500, leaving a balance only, in their hands, to her credit, of £11. She had the necessity of renewing bills frequently as they became due, and on the 24th of April, 1849, she had to renew a bill of hers, to a Mr. M , for a very large amount, which would fall due on the 30th of the following month of May; four days only before " the great debt of all debts" was to be paid by her.

In the spring of 1849, the long-menaced break-up of the establishment of Gore House took place. Numerous creditors, bill discounters, money lenders, jewellers, lace venders, tax collectors, gas company agents, all persons having claims to urge, pressed them at this period simultaneously. An execution for a debt of £4000 was at length put in by a house largely engaged in the silk, lace, India shawls and fancy jewellery business. Some arrangements were made, a life insurance was effected, but it became necessary to determine on a sale of the whole of the effects for the interest of all the creditors. Several of the friends of Lady Blessington urged on her pecuniary assistance, which would have prevented the necessity of breaking up the establishment. But she declined all offers of this kind. The fact was, that Lady Blessington was sick at heart, worn down with cares and anxieties, wearied out.

In the spring of 1849, the long-menaced break-up of the establishment of Gore House took place. Numerous creditors, bill discounters, money lenders, jewellers, lace venders, tax collectors, gas company agents, all persons having claims to urge, pressed them at this period simultaneously. An execution for a debt of £4000 was at length put in by a house largely engaged in the silk, lace, India shawls and fancy jewellery business. Some arrangements were made, a life insurance was effected, but it became necessary to determine on a sale of the whole of the effects for the interest of all the creditors. Several of the friends of Lady Blessington urged on her pecuniary assistance, which would have prevented the necessity of breaking up the establishment. But she declined all offers of this kind. The fact was, that Lady Blessington was sick at heart, worn down with cares and anxieties, wearied out.In the spring of 1849, the long-menaced break-up of the establishment of Gore House took place. Numerous creditors, bill discounters, money lenders, jewellers, lace venders, tax collectors, gas company agents, all persons having claims to urge, pressed them at this period simultaneously. An execution for a debt of £4000 was at length put in by a house largely engaged in the silk, lace, India shawls and fancy jewellery business. Some arrangements were made, a life insurance was effected, but it became necessary to determine on a sale of the whole of the effects for the interest of all the creditors. Several of the friends of Lady Blessington urged on her pecuniary assistance, which would have prevented the necessity of breaking up the establishment. But she declined all offers of this kind. The fact was, that Lady Blessington was sick at heart, worn down with cares and anxieties, wearied out.

For about two years previous to the break-up at Gore House, Lady Blessington lived in the constant apprehension of executions being put in, and unceasing precautions in the admission of persons had to be taken both at the outer gate and hall door entrance. For a considerable period too, Count D'Orsay had been in continual danger of arrest, and was obliged to confine himself to the house and grounds, except on Sundays, and in the dusk of the evening on other days. All those precautions were, however, at length baffled by the ingenuity of a sheriff's officer, who effected an entrance in a disguise, the ludicrousness of which had some of the characteristics of farce, which contrasted strangely and painfully with the denouement of a very serious drama.

Lady Blessington was no sooner informed, by a confidential servant, of the fact of the entrance of a sheriff's officer, and an execution being laid on her property, than she immediately desired the messenger to proceed to the Count's room, and tell him that he must immediately prepare to leave England, as there would be no safety for him, once the fact was known of the execution having been levied. The Count was at first incredulous—bah ! after bah ! followed each sentence of the account given him of the entrance of the sheriff's officer. At length, after seeing Lady Blessington, the necessity for his immediate departure became apparent. The following morning, with a single portmanteau, attended by his valet, he set out for Paris, and thus ended the London life of Count D'Orsay.

The public sale of the precious articles of a boudoir, the bijouterie and beautiful objects of art of the salons of a lady of fashion, awakens many reminiscences identified with the vicissitudes in the fortunes of former owners, and the fate of those to whom these precious things belonged. Lady Blessington, in her " Idler in France," alludes to the influence of such lugubrious feelings, when she went the round of the curiosity shops on the Quai D'Orsay, and made a purchase of an amber vase of rare beauty, said to have belonged to the Empress Josephine.

" When I see the beautiful objects collected together in these shops, I often think of their probable histories, and of those to whom they belonged. Each seems to identify itself with the former owner, and conjures up in my mind a little romance." Vases of exquisite workmanship, chased gold etuis enriched with oriental agate and brilliants that had once probably belonged to some grandes dames of the Court: pendules of gilded bronze, one with a motto in diamonds on the back—' vous me faites oublier les heures'—a nuptial gift: a flacon of most delicate workmanship, and other articles of bijouterie bright and beautiful as when they left the hands of the jeweller ; the gages d'amour arc scattered all around. But the givers and receivers, where are they? Mouldering in the grave, long years ago.

" Through how many hands may these objects have passed since death snatched away the persons for whom they were originally designed. And here they are, in the ignoble custody of some avaricious vender, who having obtained them at the sale of some departed amateur for less than their first cost, now expects to extort more than double the value of them. ..." And so will it be when I am gone," as Moore's beautiful song says; the rare and beautiful bijouteries which I have collected with such pains, and looked on with such pleasure, will probably be scattered abroad, and find their restingplaces not in gilded salons, but in the dingy coffers of the wily brocanteurs, whose exorbitant demands will preclude their finding purchasers."

The property of Lady Blessington offered for sale was thus eloquently described in the catalogue, composed by that eminent author of auctioneering advertisements, Mr. Phillips:

" Costly and elegant effects, comprising all the magnificent furniture, rare porcelain, sculpture in marble, bronzes, and an assemblage of objects of art and decoration, a casket of valuable jewellery and bijouterie, services of rich chased silver and silver gilt plate, a superbly fitted silver dressing case, collection of ancient and modern pictures, including many portraits of distinguished persons, valuable original drawings and fine engravings, framed and in the portfolio, the extensive and interesting library of books, comprising upwards of 5000 volumes, expensive table services of china and rich cut glass, and an infinity of valuable and useful effects, the property of the Right Hon. the Countess of Blessington, retiring to the Continent."

On the 10th of May, 1849, I visited Gore House for the last time. The auction was going on. There was a large assemblage of people of fashion. Every room was thronged; the well known library saloon, in which the conversaziones took place, was crowded, but not with guests. The arm-chair in which the lady of the mansion was wont to sit, was occupied by a stout coarse gentleman of the Jewish persuasion, busily engaged in examining a marble hand extended on a book—the fingers of which were modelled from a cast of those of the absent mistress of the establishment. People as they passed through the room poked the furniture, pulled about the precious objects of art, and ornaments of various kinds, that lay on the table. And some made jests and ribald jokes on the scene they witnessed.

It was a relief to leave that room: I went into another, the dining room, where I had frequently enjoyed, " in goodly company," the elegant hospitality of one who was indeed a " most kind hostess." I saw an individual among the crowd of gazers there, who looked thoughtful and even sad. I remembered his features. I had dined with the gentleman more than once in that room. He was a humourist, a facetious man—one of the editors of "Punch," but he had a heart, with all his customary drollery and penchant for fun and raillery. I accosted him, and said, " We have met here under different circumstances." Some observations were made by the gentleman, which shewed he felt how very different indeed they were. I took my leave of Mr. Albert Smith, thinking better of the class of facetious persons who are expected to amuse society on set occasions, as well as to make sport for the public at fixed periods, than ever I did before.

In another apartment, where the pictures were being sold, portraits by Lawrence, sketches by Landseer and Maclise, innumerable likenesses of Lady Blessington, by various artists ; several of the Count D'Orsay, representing him driving, riding out on horseback, sporting, and at work in his studio; his own collection of portraits of all the frequenters of note or mark in society of the Villa Belvedere, the Palazza Negrone, the Hotel Ney, Seamore Place, and Gore House, in quick succession, were brought to the hammer. One whom I had known in most of those mansions, my old friend, Dr. Quin, I met in this apartment.

This was the most signal ruin of an establishment of a person of high rank I ever witnessed. Nothing of value was saved from the wreck, with the exception of the portrait of Lady Blessington, by Chalon, and one or two other pictures. Here was a total smash, a crash on a grand scale of ruin, a compulsory sale in the house of a noble lady, a sweeping clearance of all its treasures. To the honour of Lady Blessington be it mentioned, she saved nothing, with the few exceptions I have referred to, from the wreck. She might have preserved her pictures, objects of virtu, bijouterie, etc. of considerable value; but she said all she possessed should go to her creditors.

There have been very exaggerated accounts of the produce of the sale of the effects and furniture of Lady Blessington at Gore House. I am able to state on authority, that the gross amount of the sale was £13,385, and the net sum realised was £11,985 4s. When it is considered that the furniture of this splendid mansion was of the most costly description, that the effects comprised a very valuable library consisting of several thousand volumes, bijouterie, ormolu candelabras and chandeliers, porcelain and china ornaments, vases of exquisite workmanship, a number of pictures by first-rate modern artists, the amount produced by the sale will appear by no means large.

The portrait of Lady Blessington, by Lawrence, which cost originally only £80, I saw sold for £336. It was purchased for the Marquis of Hertford. The portrait of Lord Blessington, by the same artist, was purchased by Mr. Fuller for £68 5s. Landseer's celebrated picture of a spaniel sold for £150 10s. Landseer's sketch of Miss Power was sold for £57 10s. Lawrence's pictures of Mrs. Inchbald were sold for £4 8 6s.

The admirable portrait of the Duke of Wellington, by Count D'Orsay, was purchased for £189, for the Marquis of Hertford. This picture was D'Orsay's chef-d'œuvre. The Duke, I was informed by the Count, spoke of this portrait as the one he would wish to be remembered by in future years. He used frequently, when it was in progress, to come of a morning, in full dress, to Gore House, to give the artist a sitting. If there was a crease or a fold in any part of the dress which he did not like, he would insist on its being altered. To use D'Orsay's words, the Duke was so hard to be pleased, it was most difficult to make a good portrait of him. When he consented to have any thing done for him, he would have it done in the best way possible.

The admirable portrait of the Duke of Wellington, by Count D'Orsay, was purchased for £189, for the Marquis of Hertford. This picture was D'Orsay's chef-d'œuvre. The Duke, I was informed by the Count, spoke of this portrait as the one he would wish to be remembered by in future years. He used frequently, when it was in progress, to come of a morning, in full dress, to Gore House, to give the artist a sitting. If there was a crease or a fold in any part of the dress which he did not like, he would insist on its being altered. To use D'Orsay's words, the Duke was so hard to be pleased, it was most difficult to make a good portrait of him. When he consented to have any thing done for him, he would have it done in the best way possible.The sale of the pictures, plate, and jewels did not a little towards cancelling Lady Blessington's debts. Her portrait by Lawrence and that of Wellington by D'Orsay were bought by the Marquis of Hertford and may be viewed by the curious, the one in the Wallace Collection, the other in the National Portrait Gallery. Everything was scattered and the house was put for a time to inglorious uses, being turned into a restaurant run by famed chef, Soyer, during the Great Exhibition of 1851. Later it was entirely swept away. Now the Albert Memorial Hall occupies a part of the site.

Published on July 13, 2016 05:30

July 10, 2016

A TOUR GUIDE IN ENGLAND: DAY 2 - PART 2

After watching the Changing of the Guard at Buckingham Palace, Diane and I skirted St. James's Park and noted all the glorious gardens in full bloom, above and below.

Crossing the Mall, we then walked up the path that runs along Green Park up to Piccadilly, but instead we turned in at Milkmaid's Passage as short cut through to St. James's Street.

I wanted to introduce Diane to Boulestin, a favourite restaurant of Victoria's and mine in St. James's Street. In fact, I like it so well that I've included it on the itineraries for several upcoming tours as a dinner venue.

The restuarant is a revival of Marcel Boulestin's pre-war venue in Covent Garden and has achieved the perfect blend of modern chic, French flair and historic touches. Click here to read about the original restaurant, the most expensive in London, and about chef Marcel Boulestin.

In the photo above, you can see the outdoor seating area which is in Pickering Place, which is also adjacent to Berry Brothers and which was also the site of the last public duel in England.

Diane and I each had a bowl of homemade soup and shared a cheese plate afterwards. Delicious!

Afterwards, we detoured through Jermyn Street in order to pay a visit to an old and dear friend.

Then it was on to meet another old friend, antique dealer Mark Sullivan, whose shop is in Cecil Court.

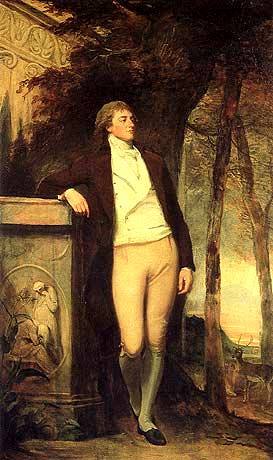

After pouring Diane and I a glass of wine each, it was at least a half hour of catch up before we got to the business at hand - Artie-facts, the true reason for our visit. As usual, Mark had found me another Wellington for my collection, and what a corker!

As you can see, he's right at home now and fits beautifully into the collection.

We decided to end the afternoon seeing even more of our pals, so Diane and I headed over to the Regency section at the National Portrait Gallery.

Part Three Coming Soon!

Published on July 10, 2016 08:43

July 9, 2016

A TOUR GUIDE IN ENGLAND: DAY TWO - PART ONE

Diane Gaston and I began our first full day in London with a gentle stroll through the area around our hotel. Walking London, with no destination in mind, is a favourite pastime of mine, as one never knows just what one might see.

Can you hear me now?

Interesting rear elevations and roofs of buildings, above. Would love to see what's in that domed turret room, wouldn't you?

Yes, of course I thought of the Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Westminster Abbey

This Ben needs no introduction.

Too bad it was so early in the day and this pub was still closed. Will have to return and have a poke about.

"Look, Diane, Cockpit Steps. Let's take them and see where they lead."

They led us to Birdcage Walk!

We backed up a few steps so that I could take a look at Queen Anne's Gate. In his diaries, James Lees-Milne relates that he and a friend were walking here just after a bomb had been dropped on the nearby Guard's Chapel during WWII. Miraculously, all the houses in the Gate survived unscathed except for most windows. What's the significance of Number 36? Until 2004, it was the headquarters for the National Trust but has been bought and renovated more recently. Read about it here.

Back in Birdcage Walk, we saw the Chapel James Lees-Milne had written about, which took a direct hit from that bomb that shattered windows in Queen Anne's Gate. The bomb hit on a Sunday. During church services. 141 people, including the Chaplain, were killed. Heartbreaking. You can read further about it here.

Before long, we'd arrived at the Palace, our home away from home, where there was a large crowd gathered. Something must be going on, thought I. I wonder what it is?

"Excuse me, officer, but can you tell me what's going on?"

Honest to God, the cop looked at me like I had two heads and said, "Changing of the Guard, madam."

More of Day Two coming soon!

Published on July 09, 2016 23:00

July 6, 2016

ONCE AGAIN WEDNESDAY - Mr. Phillip's' Auction Offices - Part One

Mention of venerable London auction houses invariably brings to mind Christie's, in King Street. But there was another auction firm who held some of the most anticipated, and most unique, auctions in the City. The London firm of auctioneers known as Phillips and Son of 73, New Bond Street, was founded by Harry Phillips in 1796. Phillips died in October of 1839 at his house at Worthing, age 73, and was succeeded by his son, who, with his son, son-in-law, and Mr. Frederick Neale, carried on the business of fine art and general auctioneers. Amongst some of the more important art sales by this firm were: The Beckford Collection at Fonthill Abbey, Sir Simon Clarke's engravings; a thirty-days' sale of engravings from Paris; the Duke of Buckingham's engravings, in 1830; Duke of Lucca's Collection, in 1841; the Count de Morny's Collection, in 1848; Lady Blessington's property, in 1849; Lord Northwick's pictures, in 1859; the Marquis of Hastings' pictures, books, and engravings, in 1869; Sir Charles Rushout's pictures and engravings in 1880, including a small collection of about one hundred examples by Bartolozzi (many duplicates) in a folio, which sold for 225 guineas. Another lot in the same sale, containing ninety-eight prints by Bartolozzi and school, sold for 174 guineas.

A book titled Art Sales of 1891 sheds some light on what the going rates for auction houses of that day were - The commissions charged are 7 per cent, on pictures, plate, jewels, porcelain, wine and effects, sculpture, and modern drawings, and 12 per cent, on engravings, books, manuscripts, sketches, coins, medals, antique gems, and old drawings, 5 per cent, being charged on unsold or bought-in lots under £100, and 2 percent, exceeding that sum. For furniture at private houses or in the country the charge is 10 per cent. There is no charge for making valuations for probate if the property is subsequently sold by auction. To secure a day at Messrs. Christie's, application must be made some months beforehand, and Saturdays in the season are allotted only to exceptionally fine collections.

Still, many of those who had their property sold by auction were in no position to balk at the terms, as they were either badly in hock to creditors or deceased, as evidenced by the following piece which ran in The Gentleman's Magazine 1805 – Mr. Phillip Auction-room, New Bond-street, was crowded with nobility and persons of distinction. After the sale of several choice lots of china, statues, and Mr. Phillips stated the conditions of sale of the elegant house and furniture, in Hill-street, Berkeley-square, belonging to Mr. Robert Heathcote. The auctioneer referred to the printed particulars, which were in the hands of the company, for the minute description of this elegant mansion, held under a lease from Earl Berkeley, for an unexpired term of 30 years, at a ground rent of 11 l. 7 s. 6d.; and, he stated, that the cost to Mr. Heathcote had been as follows: For the lease, £6000. to Mr. Cundy, the architect, whose taste and judgment had been so conspicuously displayed in the new arrangement and fitting-up of the house, and particularly in the erection of the new and superb library . . . After stating, that every article in Mr. Heathcote's house at present, except plate, jewels, linen, books, pictures, wines, china, glass-ware, and apparel, would go to the purchaser, the biddings commenced with 1, 000 guineas, on which several advances we're made from different parts of the room, till they got up to £10,000, when the contest lay entirely between two gentlemen, who were rather tardy in their advances of 50 and 100 guineas at a time, till at length it was knocked down to P. Phillips, esq.

Another entry reads -

Furniture Of Napoleon—On Wednesday a sale by auction of the property of the late Sir Hudson Lowe, including some portion of the furniture which was in the possession of the Emperor Napoleon at St. Helena, took place at the auction rooms of Mr. Phillips, by order of the executors of Sir Hudson Lowe. These consisted of about twenty lots, and among them were a large mahogany frame indulging chair, banded with ebony, on castors, from the Emperor's study, 15/. 5s.; a small circular mahogany pillar and claw table, on which Napoleon burnt pastiles, 61. 6s.; a six-foot pedestal library table, formed of mahogany and yew tree, on which table he almost always wrote, 18. 18s.; an ebonied arm chair, with cane seat and back, formed of common materials (there was a hole in the cane seat which had been caused by being constantly used, and it was stated by some brokers in the room not to be worth 1s. 6.) From the chair being light it was carried about by the Emperor when he took his walks M Longwood. It was bought for £6.

One sale that was the destined to be the auction of the year, if not the decade, was that of Fonthill Abbey, owned by William Beckford, the author of Vathek. Beckford had commissioned architect James Wyatt to design the Abbey and very few people were invited inside whilst Beckford resided there. For a complete look at both Beckford and the auction we turn to The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction -

One sale that was the destined to be the auction of the year, if not the decade, was that of Fonthill Abbey, owned by William Beckford, the author of Vathek. Beckford had commissioned architect James Wyatt to design the Abbey and very few people were invited inside whilst Beckford resided there. For a complete look at both Beckford and the auction we turn to The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction - THE LATE WILLIAM BECKFORD. From the newspapers we learn that the author of "Vathek'' is no more. He died last week at Bath, where he had erected a singular edifice, in some respects a miniature of his former abode, the far-famed Fonthill Abbey.

Beckford squandered his money in the most reckless manner, and at his bidding Fonthill arose, one of the wonders of the world. He bought Gibbon's library, and left it locked up at Lausanne, and the reason he gave for the purchase was that he might have some books to read when he happened to visit that town. It was not the splendour of Fonthill Abbey —though that was great—nor the value of its contents—though on these immense sums had been expended—that fixed public attention on Fonthill Abbey, so much as the habits of the proprietor, exaggerated, and, in all probability, misrepresented, by report. He was said to see no company, to allow no approach— but to live in almost regal state. Though he had servants fitting his opulence, his favourite was understood to be a dwarf, called Pero. Mr. Beckford was described to be violent. He would speak harshly, or more than speak, to a servant or a villager that came in his way, but, soon relenting, it was his care nobly to recompense the party he had outraged. It was shrewdly suspected that some of those who experienced the throb of his impetuous anger had artfully put themselves in the way of it, for the sake of the healing donation which was likely to follow.

He certainly lived in seclusion for a number of years, and objected to the abbey being shown to the curious. It was even said, George IV, when Prince of Wales, had intimated a wish to visit it, which had been met by something like a refusal. Be this as it may, it got wind among the public that the residence of Mr. Beckford was "a sealed book;" and when, in 1822, the news burst on the town that the abbey and all its contents were about to be on public view, preparatory to a sale by auction, every one was anxious to see the Palace of Wonders. It was likened to throwing open the blue-room of Bluebeard.

It is not surprising that so eccentric a man excited the popular wonder, and that when in consequence of the depreciation of his West India property he decided to sell Fonthill via an auction conducted by Mssrs. Christie, the public excitement was intense: Fonthill, which had been talked about by the whole nation but only seen by a very few. This was in 1822. Seven thousand two hundred catalogues were sold at a guinea each to those who wished to see the place. However, it was not disposed of by Mr. Christie at public auction, but sold en masse to Mr. John Farquhar for £330,000. Beckford reserved, however, some of his choicest books, pictures, and curiosities.

It is not surprising that so eccentric a man excited the popular wonder, and that when in consequence of the depreciation of his West India property he decided to sell Fonthill via an auction conducted by Mssrs. Christie, the public excitement was intense: Fonthill, which had been talked about by the whole nation but only seen by a very few. This was in 1822. Seven thousand two hundred catalogues were sold at a guinea each to those who wished to see the place. However, it was not disposed of by Mr. Christie at public auction, but sold en masse to Mr. John Farquhar for £330,000. Beckford reserved, however, some of his choicest books, pictures, and curiosities. The whole property had been bought by the late Mr. H. Phillips for a Mr. Farquhar, a Scotsman, of very penurious habits, who had mode a vast fortune in India, but who continued to dress and to live in the meanest style. He bought this palace and park, not because, like old Scrooge, a dream had induced him to rush from grinding parsimony to openhearted benevolence, but because it appeared a good opportunity for increasing his store, aided by the experience and talent of the Bond-street auctioneer. It is true he took up his abode in it for a time, but he bought it not to inhabit, but to sell, and accordingly it was announced in the following year that the whole, as the phrase is, was to be brought to the hammer. The ensuing sale occupied thirty-seven days.

Mr. Beckford's library was very extensive, yet, among the countless ranges of books which he possessed, he had so extraordinary a memory, that he could at once indicate the shelf, and the part of the shelf, on which any particular volume might he found. This was proved, to the utter amazement of the new proprietor of Fonthill. In many of the works, notes had been made, in the handwriting of Mr. Beckford: the books which contained them were intended to be withdrawn, but, by accident, some escaped discovery; they were discovered by the prying gentlemen of the press, and the memoranda found in several of the books appeared in the newspapers. They were eagerly sought after at the sale, though frequently they presented but quotations from the books: occasionally, however, they expressed opinions, and some of them were of a most singular nature. High prices were given for these, and some, it was understood, were purchased for Mr. Beckford at twenty times the price which the holder had given for them at the sale. His thoughts were often expressed with great force. In one instance, speaking of human nature, he powerfully marked his sense of the humanising power of letters. He pointed to the mind of man as wretched in its native state — as " blood-raw, till cooked by education."

Mr. Beckford's library was very extensive, yet, among the countless ranges of books which he possessed, he had so extraordinary a memory, that he could at once indicate the shelf, and the part of the shelf, on which any particular volume might he found. This was proved, to the utter amazement of the new proprietor of Fonthill. In many of the works, notes had been made, in the handwriting of Mr. Beckford: the books which contained them were intended to be withdrawn, but, by accident, some escaped discovery; they were discovered by the prying gentlemen of the press, and the memoranda found in several of the books appeared in the newspapers. They were eagerly sought after at the sale, though frequently they presented but quotations from the books: occasionally, however, they expressed opinions, and some of them were of a most singular nature. High prices were given for these, and some, it was understood, were purchased for Mr. Beckford at twenty times the price which the holder had given for them at the sale. His thoughts were often expressed with great force. In one instance, speaking of human nature, he powerfully marked his sense of the humanising power of letters. He pointed to the mind of man as wretched in its native state — as " blood-raw, till cooked by education."With the money he received from Mr. Farquhar, Beckford purchased annuities and land near Bath. He united two houses in the Royal Crescent by a flying gallery extending over the road, and his dwelling became one vast library. In 1810 Beckford's second daughter, Susanna Euphemia, married Alexander, Marquis of Douglas, who succeeded his father as 10th Duke of Hamilton, and to her he left all his property. Beckford died at Bath on May 2, 1844, aged 84. Most of Fonthill Abbey collapsed under the weight of its poorly-built tower the night of 21 December 1825.

This link will bring you to the catalogue for the Fonthill Abbey Library of 20,000 books

Also in 1822, on 9 February, Phillips auctioned the contents of Bradenburgh House upon the death of the Queen. Phillips's royal connections continued, as evidenced by this piece from the Annual Register of 1831 - Sale Of His Late Majesty's Coronation Robes.— A portion of his late Majesty's costly and splendid wardrobe destined for public sale, including the magnificent coronation robes and other costumes, was sold by auction, by Mr. Phillips, at his rooms in New Bond Street. There were 120 lots disposed of, out of which we subjoin the principal in the order in which they were put up :— No. 13. An elegant yellow and silver sash of the Royal Hanoverian Guelphie Order, 3/. 8.— 17. A pair of fine kid-trousers, of ample dimensions, and lined with white satin, was sold for 12.v.— 35. The coronation ruff, formed of superb Mechlin-lace, 2/.—50. The costly Highland costume worn by our late Sovereign at Dalkeith Palace, the seat of his Grace the Duke of Buccleugh, in the summer of 1822, was knocked down at 40/.— 52. The sumptuous crimson-velvet coronation mantle, with silver star, embroidered with gold, on appropriate devices, and which cost originally, accordiug to the statement of the auctioneer, upwards of 500/., was knocked down at 47 guineas.—53. A crimson coat to suit with the above, 14/. - 55. A magnificent gold body-dress and trousers, 26 guineas.—67- An extraordinary large white aigrette plume, brought from Paris by the Earl of Fife, in April, 1815, and presented by his lordship to the late King, was sold for 15/.—87. A richly embroidered silver tissue coronation waistcoat and trunk hose, 13/.—95. The splendid purple velvet coronation mantle, sumptuously embroidered with gold, of which it was said to contain 200 ounces. It was knocked down at 55/., although it was stated to have cost his late Majesty 300/.—96. An elegant and costly green velvet mantle, lined with ermine of the finest quality; presented by the Emperor Alexander to his late Majesty, which cost upwards of 1,000 guineas, was knocked down at 125/.

Part Two, featuring the Blessington/D'Orsay Auction, coming soon . . . . .

Originally published August 2010

Published on July 06, 2016 00:00

July 2, 2016

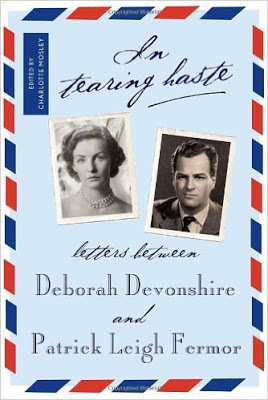

ON THE SHELF: IN TEARING HASTE

You would think that after having read the massive The Mitfords: Letters Between Six Sisters I'd have gotten my fill of all things Mitford, but not so. In fact, the book only fueled my passion for the Sisters, so I went directly afterwards to reading In Tearing Haste: Letters Between Deborah Devonshire and Patrick Leigh Fermor. Here's a brief synopsis:

From Amazon Books: In the spring of 1956, Deborah, Duchess of Devonshire, youngest of the six legendary Mitford sisters, invited the writer and war hero Patrick Leigh Fermor to visit Lismore Castle, the Devonshires’ house in Ireland. The halcyon visit sparked a deep friendship and a lifelong exchange of highly entertaining correspondence. When something caught their interest and they knew the other would be amused, they sent off a letter—there are glimpses of President Kennedy’s inauguration, weekends at Sandringham, filming with Errol Flynn, the wedding of Prince Charles and Camilla Parker-Bowles, and, above all, life at Chatsworth, the great house that Debo spent much of her life restoring, and of Paddy in the house that he and his wife designed and built on the southernmost peninsula of Greece.

Deborah (Mitford), Duchess of Devonshire

Deborah (Mitford), Duchess of DevonshireOf course, this description does nothing to impart the flavour of the letters themselves, or their authors. Here are a few extracts:

Deborah to Paddy - 14 July 1975

"Darling (Paddy) Whack,

No news, except bumpkin stuff. The Council of the Royal Smithfield Club - top farmers and butchers from all over the British Isles, every accent from Devon to Aberdeen via Wales & Norfolk - met here on Thurs. Fifty of them. So the only room I could think of was the nursery, and there they sat good as gold on hard chairs. I offered the rocking horse, but they eschewed it, ditto high chairs and Snakes and Ladders.

I really love those men, and it's my last year as president. I shall miss it and them.

Then they had lunch, then the wives were let in (so typical of England that they had to hang about till lunch was over) and of course they wanted to see the house. I said 'I'll meet you at the end of the tour.' The first butcher was out in six minutes. I reminded him of Art Buchwald's lovely article on How to do the Louvre in Six Minutes - but he'd never heard of Art Buchwald or the Louvre so I chucked it and took him to see some cattle, which he had heard of. A really good fellow."

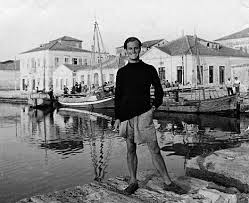

Patrick Leigh Fermor While Deborah's heart was always in her home and with her country pursuits, she often had to leave Chastsworth in order to attend to her duties as the Duchess of Devonshire, many of which brought her into contact with Royals and other members of the nobility:

Patrick Leigh Fermor While Deborah's heart was always in her home and with her country pursuits, she often had to leave Chastsworth in order to attend to her duties as the Duchess of Devonshire, many of which brought her into contact with Royals and other members of the nobility:Deborah to Paddy - 18 January 1980

"Darling Paddy -

. . . . . . Last night I went to AN OPERA. The second in my life. It was a plan of Andrew's (Duke of Devonshire) in aid of the Putney Hosp for Incurables and good Cake (the Queen Mother) came and turned it into a gala. One forgets between seeing her what a star she is and what incredible and wicked charm she has got. The Swiss conductor panicked and struck up `God Save The Queen' when she was still walking round the back to get to her box and I heard her say Oh God and she flew the last few steps dropping her old white fox cape and didn't turn round to see what would happen to it.

She does a wonderful sort of super shooting-lunch dinner, brought from Clarence House and handed round by her beautiful footmen in royal kit, between the acts, the cheeriest thing. We were a bit stumped though because when she'd gone home we had to go to the Savoy and have a second grand dinner with the organisers. It was a bit of a test forcing down sole after Cake's richest choc mousse. It's tough at the top, I can tell you . . . ."

Paddy to Deborah - 23 October 1995

"Darling Debo -

. . . . . Ages ago, I went to a party given by Brig. West. Everyone was tightish. Daph(ne Fielding), still Bath, was curled up in a ball next to a chair where Duff C(ooper) was sitting, covered in medals and decorations. Daph was wearing a tiara, as they'd all been to a Court ball. Daph was so rapt in talk and laughter that she didn't even notice or pause when Henry (Bath), on the point of buzzing off with Virginia, said, `I think I'd better take that,' neatly uncoiled the bauble from Daph's hair, and slipped it into the pocket in the tail of his tail coat, and walked away. Daph was amazed a bit later by its absence, until we reassured her. I thought for a moment that it might have been later on the same night when I came and collected you from a ball at the Savoy and took you on to another in Chelsea - whose? - a lovely evening.

No more for the moment.

Lots of love - Paddy

Was the ball at the Savoy given by someone called Christie-Miller? A yearly event? One year, they say, David Cecil was hastening to it along the Strand, when a tart stopped him and said, `Woud you like to come home with me, dear?' and he answered, 'I can't possibly. I'm going to the Christie-Millers.'"

Deborah and Patrick

Deborah and Patrick Who knew that the tails of tail coats had pockets? More importantly, these breezy, entertaining and endearing letters serve to lend an insight into the lives and hearts of their authors. Whether it's Deborah's slightly wicked sense of humour or Paddy's love of and descriptions of travel, there is something for everyone here. A must read for fans of all things Mitford.

Published on July 02, 2016 23:30

June 29, 2016

ONCE AGAIN WEDNESDAY: The Witty Lord Alvanley

There were so many un-witty imitators of dandyism in the days of the Prince Regent that the appearance of Lord Alvanley with his delicate manner and exquisite style always caused a quiet sensation. To Lord Alvanley was awarded the reputation of being able to say as smart a thing as even Richard Brinsley Sheridan could rap out, whose repartee on all occasions was equal to any need. Captain Gronow alleges that Lord Alvanley had the talk of the day completely under his control, and was the arbiter of the school for scandal in all the St. James's district. A bon mot attributed to him gave rise to the belief that Solomon caused the downfall and disappearance of Beau Brummell; for on some friends of the prince of dandies observing that if he had remained in London something might have been done for him by his old associates, Alvanley replied, "he has done quite right to be off; it was Solomon's judgment." The real point of this remark is that one of Brummell's chief creditors was a gentleman of the Jewish persuasion whose name by chance happened to be Solomon.

There were so many un-witty imitators of dandyism in the days of the Prince Regent that the appearance of Lord Alvanley with his delicate manner and exquisite style always caused a quiet sensation. To Lord Alvanley was awarded the reputation of being able to say as smart a thing as even Richard Brinsley Sheridan could rap out, whose repartee on all occasions was equal to any need. Captain Gronow alleges that Lord Alvanley had the talk of the day completely under his control, and was the arbiter of the school for scandal in all the St. James's district. A bon mot attributed to him gave rise to the belief that Solomon caused the downfall and disappearance of Beau Brummell; for on some friends of the prince of dandies observing that if he had remained in London something might have been done for him by his old associates, Alvanley replied, "he has done quite right to be off; it was Solomon's judgment." The real point of this remark is that one of Brummell's chief creditors was a gentleman of the Jewish persuasion whose name by chance happened to be Solomon.The success of Lord Alvanley's casual observations, which were evidently delivered as though he were not conscious of what the effect would be, was due to their cynical aptitude. For example, Sir Lumley Skeffington, who had been a considerable lion in his day and whose spectacle "The Sleeping Beauty" attracted much attention when it was produced at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, excited Alvanley's wit. Sir Lumley, after having met with many misadventures and a "seclusion in the Bench," hoped that by gay attire and a general jauntiness he would be able to get back into fashionable life once more. But his old friends were not very kindly disposed towards him once his stint in debtor’s prison had been completed. Observing this, Alvanley, being asked on one occasion who that smart looking individual was, answered, "it is a second edition of the 'Sleeping Beauty,' bound in calf; richly gilt and illustrated by many cuts."

Alvanley used to say that Brummell was the only dandelion that flourished year after year in the hot-bed of the fashionable world: he had taken root. Lions were generally annual, but Brummell was perennial, and he quoted a letter from Walter Scott : " If you are celebrated for writing verses, or for slicing cucumbers, for being two feet taller, or two feet less, than any other biped, for acting plays when you should be whipped at school, or for attending schools and institutions when you should be preparing for your grave, your notoriety becomes a talisman, an "open sesame," which gives way to everything till you are voted a bore, and discarded for a new plaything."

Lord Alvanley had one very great advantage over all the wits of the Regency. He had travelled in France and Russia and had the command of languages. He was equally at home in French society and Russian as he was at the Court of the King of England. We have it on record that he was one of the best examples of a man who combined a genial wit with the utmost good-nature. The slight lisp became irresistible and added zest to his piquant sayings. He was what we should term in these days a jolly man, because as he grew old he also grew rotund. And he excelled in all manly exercises, was an ardent rider to hounds, and was plucky to the core. He has been described as having the happy face of one of the happy friars, whose portraits are always a joy to look upon. He had, of course, his peculiarities, and one of them was that he would have an apricot tart on the sideboard the whole year round, no matter if apricots were not in season, and he always invited eight people to dinner, when, as can be understood, they feasted of the best. Yet this good-humoured epicure was once in a risky affair.

It happened that Lord Alvanley made some strong allusions to O'Connell in the House of Lords, which resulted in a duel on Wimbledon Common. Morgan O'Connell said he would take his father's place, and did so. Alvanley's second was Colonel George Dawson Damer, while Colonel Hodges acted for Morgan O'Connell. It appears that several shots were fired without effect, and the seconds then interfered and put a stop to any further hostilities. On their way home in a hackney coach, Alvanley said, "What a clumsy fellow O'Connell must be, to miss such a fat fellow as I am. He ought to practise at a haystack to get his hand in." When the carriage drove up to Alvanley's door, he gave the coachman a sovereign. The man was profuse in his thanks, and said: "It's a great deal for only having taken your lordship to Wimbledon." "No, my good man," said Alvanley, " I give it to you, not for taking me, but for bringing me back."

One of the greatest charms of Alvanley's manner was its easy naturalness. He was an excellent classical scholar, a good speaker, and whatever he undertook to do he succeeded in. He preserved his wit and good-humour to the last; notwithstanding the gout, from which he suffered. He died "quite agreeably," as he said to friends at his bedside, in 1849.

Originally published April 2010

Published on June 29, 2016 04:01

June 26, 2016

A TALE OF TWO PALACES BY GUEST BLOGGER AMANDA MCCABE

One of the best perks of writing historical mysteries is the research! I am a library junkie, and love spending time digging through dusty old books in search of just the right historical detail. (Of course, this also means sometimes it's hard for me to stop researching and actually, y'know, use the research in writing!). Travel is also a fun way to immerse myself in a period, to imagine how my characters might have actually lived in Elizabethan times. Murder at Fontainebleau uses a sense of place even more than other stories I've written. We glimpse two palaces in the story, one the is long demolished and one that still exists to be toured, and they were a perfect example of the differences between English and French life in the 16th century, which Kate Haywood discovers for herself when she's sent to Fontainebleau on a mission for Queen Elizabeth....

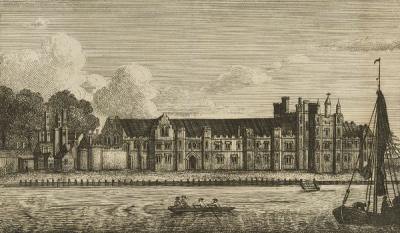

The English palace, Greenwich (above), was originally built in 1433 by Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, a brother of Henry V. It was a convenient spot for a castle, 5 miles from London and Thames-side, and was popular with subsequent rulers, especially Henry VIII. His father, Henry VII, remodeled the place extensively between 1498-1504 (after dispatching the previous occupant, Dowager Queen Elizabeth, to a convent). The new design was after the trendy “Burgundian” model, with the facade refaced in red Burgundian brick. Though the royal apartments were still in the “donjon” style (i.e. stacked rooms atop rooms), there were no moats or fortifications. It was built around 3 courtyards, with the royal apartments overlooking the river and many fabulous gardens and mazes, fountains and lawns.At the east side of the palace lay the chapel; to the west the privy kitchen. Next door was the church of he Observant Friars of St. Francis, built in 1482 and connected to the palace by a gallery. This was the favorite church of Katherine of Aragon, who wanted one day to be buried there (of course, that didn’t turn out quite as she planned…)Though there are paintings and drawings of the exterior, not much is known of the interior decorations. The Great Hall was said to have roof timbers painted with yellow ochre, and the floors were wood, usually oak (some painted to look like marble). The ceilings were flat, with moulded fretwork and lavish gilding, embellished with badges and heraldic devices (often Katherine’s pomegranates and Henry’s roses). The furniture was probably typical of the era, carved dark wood chairs (often an X-frame design) and tables, benches and trunks. Wool or velvet rugs were on the floors of the royal apartments only, but they could also be found on tables, cupboards, and walls. Elaborate tiered buffets showed off gold and silver plate, and treasures like an gold salt cellar engraved with the initials “K and H” and enameled with red roses.It was a royal residence through the reign of Charles I (1625-49), but under the Commonwealth the state apartments were made into stables, and the palace decayed. In 1662, Charles II demolished most of the remains and built a new palace on the site (this later became the Royal Naval College), and landscaped Greenwich Park. The Tudor Great Hall survived until 1866, and the chapel (used for storage) until the late 19th century. Apart from the undercroft (built by James I in 1606) and one of Henry VIII’s reservoir buildings of 1515, nothing of the original survives.

Fontainebleau (above), on the other hand, can be seen in much the state Francois I left it in. On February 24, 1525 there was the battle of Pavia, the worst French defeat since Agincourt. Many nobles were dead, and king was the prisoner of the Holy Roman Emperor in Madrid. He was released in May, but only at the price of exchanging his sons (Dauphin Francois and Henri, duc d’Orleans) for his own freedom. In May 1526, Francois created the League of Cognac with Venice, Florence, the Papacy, the Sforzas of Milan, and Henry VIII to “ensure the security of Christendom and the establishment of a true and lasting peace.” (Ha!!) This led to the visit of the delegation in 1527, seeking a treaty of alliance with England and the betrothal of Princess Mary and the duc d’Orleans.After his return from Madrid, Francois was not idle. Aside from plotting alliances, he started decorating. Having finished Chambord, he turned to Fontainebleau, which he loved for its 17,000 hectares of fine hunting land. All that remained of the original 12th century castle was a single tower. Francois built new ballrooms, galleries, and a chapel, and called in Italian artists like Fiorentino, Primaticcio, and Vignola to decorate them in lavish style (some of their work can still be seen in the frescoes of the Gallery of Francois I and the bedchamber of the king’s mistress the duchesse d’Etampes). The marble halls were filled with artworks, gold and silver ornaments, and fine tapestries. Unlike Greenwich, this palace was high and light, filled with sunlight that sparkled on the giltwork.I know it’s hard to comment on a research-type post, but I’m curious–after reading about both palaces, which would you prefer to live in? (I’m torn, but I lean toward Fontainebleau, just because I was so awestruck when I visited!). Where would you like to see a book set?

For more behind-the-scenes history tidbits, and info on the KateHaywood Elizabethan Mysteries, please visit me at this link.

Published on June 26, 2016 23:30

June 24, 2016

A TOUR GUIDE IN ENGLAND - DAY 1

As some of you already know, I flew over to England at the beginning of May in order to firm up details for the 2017 tours to Great Britain that Number One London will soon be offering (watch this space!). Luckily, my old pal Diane Gaston (Perkins) was able to join me on my travels. I'd warned her ahead of time that I would be on a mission on the trip over; there were people I needed to meet and places I needed to be. We'd be traveling hither and yon across the country via British Rail. We'd be spending at most two nights in a city or town and then moving on. Places to go, people to see. I did warn her. She still said "yes!"

And I warned myself, as I usually do, not to plan anything for my first day in London. No plans, no commitments, just an entire, luxurious day in order to laze around and recover from east to west jetlag. I warned Diane that we weren't going to plan anything, too. Again, she was on board with that. And then I saw online that Buckingham Palace was once again doing their unscheduled private, champagne evening tours of the Palace. Three nights only, the last night being that of the day we were to land. I called Diane and asked her whether we should forget the no plans thing and get tickets. She said "yes!"

Diane and I met at Heathrow and we drove into central London together. Below is one of the first signs we saw - fitting, no?

Before long we had reached our hotel, the St. James's Court, below. Once we'd arrived in our room, I asked Diane if she were tired.

"Not really," she answered. "Are you?"

"No. I'm actually okay. What do you feel like doing?"

"I don't know. We could always just go out and walk around. Maybe go to Westminster Abbey."

"Okay," I agreed as I logged into my Facebook account.

I read a post by Ian Fletcher, posted just moments before, saying that he was having lunch at The Admiralty in Trafalgar Square.

"Ian's in Trafalgar Square," I told Diane. "Should I ask him to meet us? I mean, he's only just down the street."

"Yes!" said Diane.

"I'll ask him to meet us at the Palace."

Some of you may already know that Diane and I are familiar with the Palace, having each been there several times previously and having taken lots of silly selfies there the last time we were together for the 2014 Duke of Wellington Tour. I sent Ian a reply to his Facebook post and asked him if he had time to meet us, setting in motion the following thread:

Kristine Hughes Patrone Walk down the Mall and meet us in front of Palace. Wear your spy trench coat in case we don't recognize your dog ears.

Kristine Hughes Patrone Walk down the Mall and meet us in front of Palace. Wear your spy trench coat in case we don't recognize your dog ears.Like · Reply · May 2 at 9:50am

Ian Fletcher I'll walk that way for a few minutes. Brown leather jacket, Crockett and Jones bag but no dog ears...

Ian Fletcher I'll walk that way for a few minutes. Brown leather jacket, Crockett and Jones bag but no dog ears...Like · Reply · May 2 at 9:55am

Kristine Hughes Patrone K. We're both in black. Witches of eastwick. I'm 2 streets away. Leave now?

Kristine Hughes Patrone K. We're both in black. Witches of eastwick. I'm 2 streets away. Leave now?Like · Reply · May 2 at 9:58am

Ian Fletcher I'm at St James's Palace. See you by the front gate of Buckingham Palace...

Ian Fletcher I'm at St James's Palace. See you by the front gate of Buckingham Palace...Like · Reply · May 2 at 9:59am

Kristine Hughes Patrone Ok give us a few leaving now

Kristine Hughes Patrone Ok give us a few leaving nowLike · Reply · May 2 at 10:05am

Ian Fletcher No problem. I'm outside. HM has put the kettle on...

Ian Fletcher No problem. I'm outside. HM has put the kettle on...Like · Reply · May 2 at 10:06am

Kristine Hughes Patrone Here

Kristine Hughes Patrone HereLike · Reply · May 2 at 10:20am

Delle Jacobs Damm I'm jealous, Kristine Hughes Patrone.

Delle Jacobs Damm I'm jealous, Kristine Hughes Patrone.Unlike · Reply · 1 · May 2 at 12:41pm

Author Delle Jacobs knows Ian because she's been on his tours before. I actually already had plans to meet with Ian later in the week, as his company, Ian Fletcher Battlefield Tours, and Number One London will be joining forces on several of the 2017 tours. In fact, Delle is in the Peninsula with Ian as I write this, tracing Wellington's path, from Torres Verdes to Oporto to Madrid.

So off Diane and I trotted, quickly covering the three blocks between our hotel and the Palace, where we found Ian waiting patiently by the iconic gates. Kisses all around and then the crucial question - booze or tea? In the end, we all agreed on tea (!?) and so walked back to our hotel, where we ordered three pots full, along with scones, cream and jam.

The next few hours passed in a flurry of conversation that covered everything from future tours to Wellington to battlefields to world travels to Jermyn Street, men's clothing and oysters. The hours flew past until Ian realized he had to be getting home and Diane and I realized that we were due at the Palace by 6 p.m. for our tour. Check, please!

And so Diane and I flew upstairs to our room in order to freshen up before, once again, making our way to the Palace.

Of course the tour of the Palace was fabulous, it's always fabulous, but photos weren't allowed. I did find a few interior shots of the Palace online, see below, but of course they don't compare to all that Diane and I saw that night. You can find a previous post I wrote about touring the Palace here.

At the end of our Palace tour, Diane and I returned to our hotel room, below, and so ended our first day in England. Stay tuned for more posts regarding our journey through England on behalf of Number One London Tours!

Published on June 24, 2016 00:00

June 21, 2016

ONCE AGAIN WEDNESDAY: Who Wants to be (or look at) a Horse's Behind?

by Victoria Hinshaw

On our post-Wellington tour jaunt around London, Kristine and I found another copy of the painting discussed below as appearing in the 1995 Pride and Prejudice film as it hangs in Brocket Hall, Hertfordshire, depicting George, the Prince of Wales, and his horse's behind. It hangs in the Theatre Royal Drury Lane.

An engraving of the painting also appears in "What Jane Saw," a digital recreation of an exhibition at he British Institution in Pall all in 1813. Click here to see the website and click again on the picture itself to read the description.

Originally published April 2010

In May of 2009, my husband and I visited Brocket Hall, formerly the home of Lord Melbourne, now part of a golf complex. The house, in excellent condition, serves as a venue for corporate events and weddings. Brocket is located near Hertford and Hatfield just north of London. Part of the original land of the adjacent country homes of the London wealthy has been developed into Welwyn Garden City.

The ballroom in Brocket was used for the interiors of Netherfield, the home rented by Mr. Bingley, in the 1995 BBC version of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice. In the picture above, you see Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth leading the country dance. In the far background, you can barely make out a portrait of George, Prince of Wales, standing beside the rump of his horse. The painting, by Sir Joshua Reynolds, was presented to Elizabeth, Lady Melbourne (mother of the Prime Minister), who reputedly was the mistress of the Prince for a time.

Here is another view of the painting behind Mr. Darcy.

I laughed when I saw this painting, a copy of which I have been unable to locate on any website pertaining either to the Prince of Wales (later George IV) or Sir Joshua Reynolds.

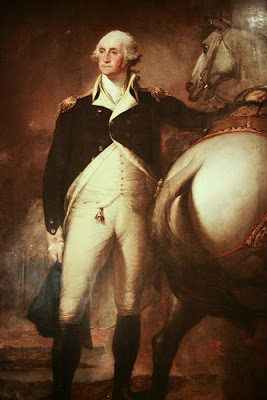

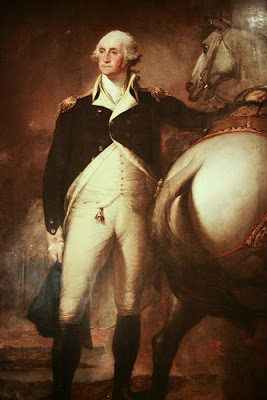

The pose reminded me of a famous view of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart. A version of this painting hung in the Elgin Academy Art Gallery where I played at my piano teacher's annual recital for her students and their parents. There are other versions of the Stuart portrait, chiefly belonging to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. I have always wondered how many of my fellow performers looked up in the middle of their playing to be faced with that horse's . . . ah . . .tail.

George Washington by Gilbert Stuart

George Washington by Gilbert Stuart

Since those youthful days, the question has arisen in my mind -- why paint the rear end of the horse so prominently? In my search of the web for a copy of the Reynolds portrait above, I found some discussions of this exact point. But no one had a definitive answer. Someone suggested that the rear of the horse was a comment by the artist on the character of the subject. One writer said Stuart was not good at painting horses. Another said that men were so portrayed because they were prepared to jump on the horse and take off -- being in a position on the horse's left easily to reach the stirrup. Anyone have any views on this world-shattering question?

The Marquis of Granby, by Sir Joshua ReynoldsAbove is another example. This is General John Manners, Marquis of Granby, who was painted by Reynolds in about 1765. He died before he succeeded to the title of Duke of Rutland. This painting hangs in the Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, Florida. The General was a popular figure, hence many pubs in England named The Marquis of Granby.

The Marquis of Granby, by Sir Joshua ReynoldsAbove is another example. This is General John Manners, Marquis of Granby, who was painted by Reynolds in about 1765. He died before he succeeded to the title of Duke of Rutland. This painting hangs in the Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, Florida. The General was a popular figure, hence many pubs in England named The Marquis of Granby.

Above, another painting by Gilbert Stuart. The subject is Louis-Marie, the vicomte de Noailles (1756-1804), who fought with the Americans during the Revolution. He returned to France but was driven out after their revolution and moved to Philadelphia in 1793. He was a banker and a friend of Washington, neither of which explains why he is standing next to his horse's rump.

Here is my final example, a portrait of Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington. It hangs at the country home of the Duke, Stratfield Saye.

I welcome any comments, clues, or links to additional poses of generals (or anyone) with their horses' rumps.

On our post-Wellington tour jaunt around London, Kristine and I found another copy of the painting discussed below as appearing in the 1995 Pride and Prejudice film as it hangs in Brocket Hall, Hertfordshire, depicting George, the Prince of Wales, and his horse's behind. It hangs in the Theatre Royal Drury Lane.

An engraving of the painting also appears in "What Jane Saw," a digital recreation of an exhibition at he British Institution in Pall all in 1813. Click here to see the website and click again on the picture itself to read the description.

Originally published April 2010

In May of 2009, my husband and I visited Brocket Hall, formerly the home of Lord Melbourne, now part of a golf complex. The house, in excellent condition, serves as a venue for corporate events and weddings. Brocket is located near Hertford and Hatfield just north of London. Part of the original land of the adjacent country homes of the London wealthy has been developed into Welwyn Garden City.

The ballroom in Brocket was used for the interiors of Netherfield, the home rented by Mr. Bingley, in the 1995 BBC version of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice. In the picture above, you see Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth leading the country dance. In the far background, you can barely make out a portrait of George, Prince of Wales, standing beside the rump of his horse. The painting, by Sir Joshua Reynolds, was presented to Elizabeth, Lady Melbourne (mother of the Prime Minister), who reputedly was the mistress of the Prince for a time.

Here is another view of the painting behind Mr. Darcy.

I laughed when I saw this painting, a copy of which I have been unable to locate on any website pertaining either to the Prince of Wales (later George IV) or Sir Joshua Reynolds.

The pose reminded me of a famous view of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart. A version of this painting hung in the Elgin Academy Art Gallery where I played at my piano teacher's annual recital for her students and their parents. There are other versions of the Stuart portrait, chiefly belonging to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. I have always wondered how many of my fellow performers looked up in the middle of their playing to be faced with that horse's . . . ah . . .tail.

George Washington by Gilbert Stuart

George Washington by Gilbert StuartSince those youthful days, the question has arisen in my mind -- why paint the rear end of the horse so prominently? In my search of the web for a copy of the Reynolds portrait above, I found some discussions of this exact point. But no one had a definitive answer. Someone suggested that the rear of the horse was a comment by the artist on the character of the subject. One writer said Stuart was not good at painting horses. Another said that men were so portrayed because they were prepared to jump on the horse and take off -- being in a position on the horse's left easily to reach the stirrup. Anyone have any views on this world-shattering question?

The Marquis of Granby, by Sir Joshua ReynoldsAbove is another example. This is General John Manners, Marquis of Granby, who was painted by Reynolds in about 1765. He died before he succeeded to the title of Duke of Rutland. This painting hangs in the Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, Florida. The General was a popular figure, hence many pubs in England named The Marquis of Granby.

The Marquis of Granby, by Sir Joshua ReynoldsAbove is another example. This is General John Manners, Marquis of Granby, who was painted by Reynolds in about 1765. He died before he succeeded to the title of Duke of Rutland. This painting hangs in the Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, Florida. The General was a popular figure, hence many pubs in England named The Marquis of Granby.

Above, another painting by Gilbert Stuart. The subject is Louis-Marie, the vicomte de Noailles (1756-1804), who fought with the Americans during the Revolution. He returned to France but was driven out after their revolution and moved to Philadelphia in 1793. He was a banker and a friend of Washington, neither of which explains why he is standing next to his horse's rump.

Here is my final example, a portrait of Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington. It hangs at the country home of the Duke, Stratfield Saye.

I welcome any comments, clues, or links to additional poses of generals (or anyone) with their horses' rumps.

Published on June 21, 2016 23:30

Kristine Hughes's Blog

- Kristine Hughes's profile

- 6 followers

Kristine Hughes isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.